Published online Oct 19, 2024. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i10.1513

Revised: September 5, 2024

Accepted: September 9, 2024

Published online: October 19, 2024

Processing time: 72 Days and 0.4 Hours

As the incidence of diabetes continues to increase, the number of patients with diabetic retinopathy (DR) also increases each year. After undergoing vitrectomy for DR, patients often experience negative emotional problems that negatively affect their recovery.

To investigate negative feelings in patients with DR after vitrectomy and to explore related influencing factors.

A total of 146 individuals with DR who were accepted for treatment at The Third People’s Hospital of Changzhou from May 2021 to April 2023 were recruited to participate in this study. All patients underwent vitrectomy. The self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) and self-rating depression scale (SDS) were used to assess the degree of anxiety and depression 2-3 days after the operation. The participants were divided into a healthy control group and a negative emotion group. The patients’ general demographic characteristics and blood glucose levels were collected. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the factors influencing negative feelings post-operation. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to analyze the association between SAS scores, SDS scores, and blood glucose levels.

The control group included 85 participants. The negative emotion group comprised 40 participants with anxiety, 13 with depression, and eight with both. Logistic regression showed that being female (OR = 3.090, 95%CI: 1.217-7.847), a family per capita monthly income of < 5000 yuan (OR = 0.337, 95%CI: 0.165-0.668), and a longer duration of diabetes (OR = 2.068, 95%CI: 1.817-3.744) were risk factors for negative emotions in patients with DR after vitrectomy (P < 0.05). The concentrations of fasting plasma glucose (FPG), 2-hour postprandial glucose (2hPG), and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in the negative emotion group exceeded those in the control group (P < 0.05). SAS scores were positively associated with FPG (r = 0.422), 2hPG (r = 0.334), and HbA1c (r = 0.362; P < 0.05). SDS scores were positively correlated with FPG (r = 0.218) and 2hPG (r = 0.218; P < 0.05).

Sex, income level, and duration of diabetes were factors that influenced negative emotions post-vitrectomy. Negative emotions were positively correlated with blood glucose levels, which can be used to develop intervention strategies.

Core Tip: This study comprehensively investigated and analyzed the level of negative emotion experienced by patients with diabetic retinopathy following vitrectomy. By employing rigorous scientific research methods, we identified the prevalent types of postoperative negative emotions and their influencing factors, aiming to provide empirical evidence for psychological interventions in clinical practice and to enhance patients’ psychological well-being and recovery processes.

- Citation: Ju ZH, Wang MJ. Investigation and analysis of negative emotion in patients with diabetic retinopathy after vitrectomy. World J Psychiatry 2024; 14(10): 1513-1520

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v14/i10/1513.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v14.i10.1513

Diabetes is a worldwide public health epidemic that is expected to affect 642 million adults by 2024[1]. Diabetic retinopathy (DR), a prevalent and distinct microvascular complication associated with diabetes, is frequently observed in individuals with diabetes. About a third of the patients with diabetes have DR[1]. The gradual progression of DR has the potential to not only result in vision loss but also elevate the likelihood of experiencing systemic vascular complications, including stroke, coronary artery disease, and cardiac insufficiency[2]. Vitrectomy is a high-level modern microophthalmic surgery that is used to maintain and restore visual function. It can remove the turbid vitreous and proliferative fibrous membranes, reset the detached retina, and significantly improve or preserve the patient's vision during the treatment of proliferative DR[3,4]. As the disease has a long disease course, long treatment time, and special post

A total of 146 individuals with DR who were accepted for treatment at The Third People’s Hospital of Changzhou from May 2021 to April 2023 were recruited to participate in this study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Clinical diagnosis of DR in line with the international diagnostic standard for DR[7]; (2) Over 18 years old; and (3) Underwent vitrectomy and completed the operation. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Type I diabetes or gestational diabetes; (2) Severe physical diseases; (3) Diabetic complications such as diabetic nephropathy and diabetic peripheral neuropathy; (4) Suffered a severe accident in the past three months; (5) Cognitive impairment and communication barriers; and (6) Poor compliance. All the patients volunteered to participate in the study and provided informed consent. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of The Third People’s Hospital of Changzhou.

General data: An individually created general information survey form was used to collect the patients’ age, sex, educational level, marital status, residential location, family income level, duration of diabetes, family history of diabetes, smoking history, comorbidities (hypertension and hyperlipidemia), and other related information.

Negative emotions: The self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) and self-rating depression scale (SDS)[8] were used to assess anxiety and depression, respectively, in individuals 2-3 days after surgery. The SAS and SDS each have 20 items and use 4-point Likert scoring to rate symptoms from mild to severe. The crude score was used to calculate the cumulative score for each item; multiplying the crude score by 1.25 yields the standard score; SAS standard score ≥ 50 suggested the existence of anxiety, SDS standard score ≥ 53 suggested the existence of depression, and the severity of anxiety and depression increases as the score increases.

Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and 2-hour postprandial glucose (2hPG) levels were assessed using a blood glucose meter (Sannuo Biosensor Co., Ltd., Model: GA-3) 2-3 days after surgery. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were measured using a HbA1c analyzer (Nanjing Beden Medical Co., Ltd., Model: AC6601).

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0 software. Quantitative data adhering to the standard bell curve distribution were characterized as mean ± SD, and an independent sample t-test was applied for comparison between groups. Qualitative data were characterized as numbers (n) and compared using the χ2 method. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used for correlation analysis. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine factors that had an impact. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

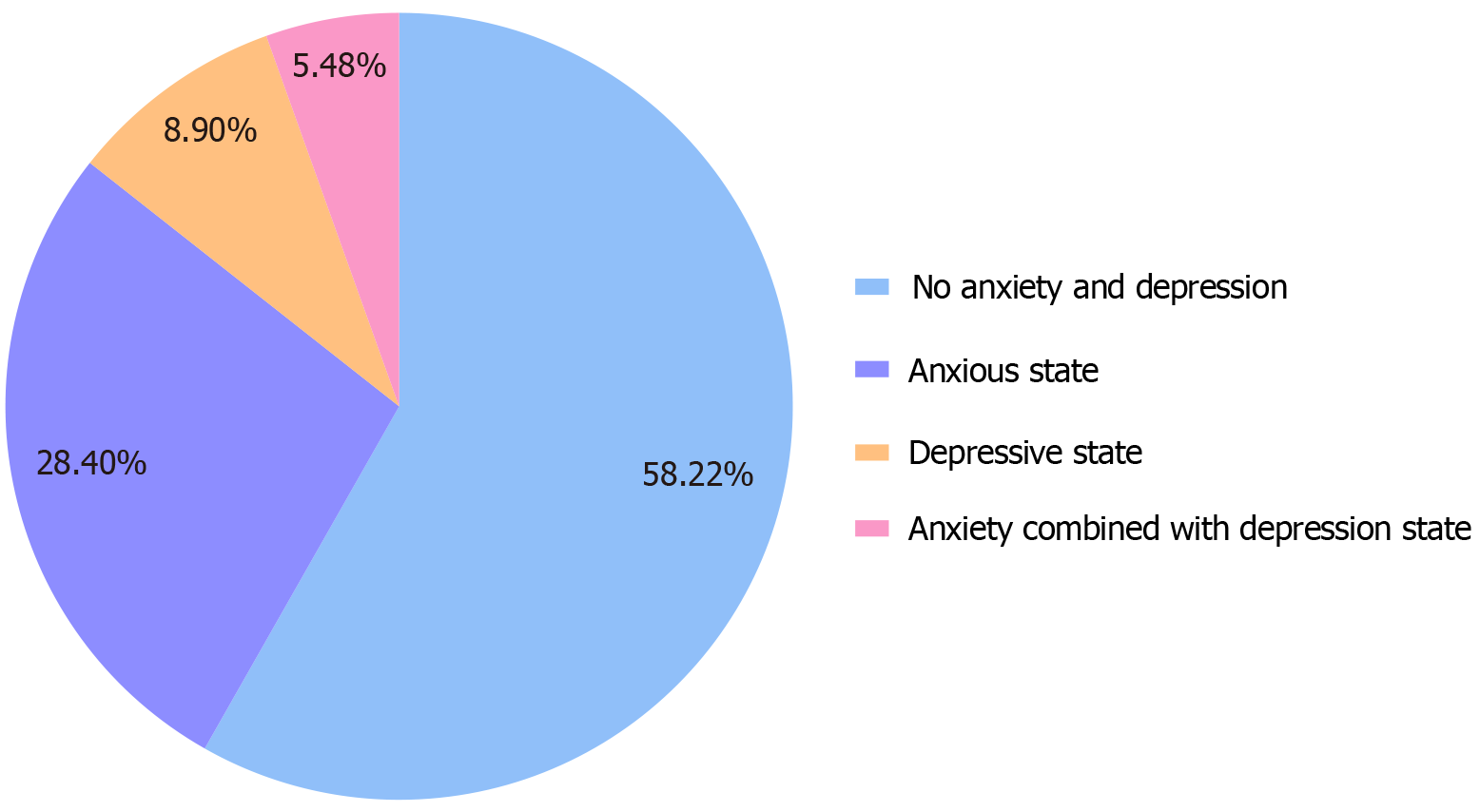

SAS scores ranged from 28-65 points, with an average of 46.62 ± 7.94 points. SDS scores ranged from 25-60 points, with an average of 43.98 ± 6.62 points. There were 40 participants with anxiety, 13 with depression, and eight with both. There were 85 participants with neither anxiety nor depression (Figure 1).

Patients without postoperative anxiety or depression were included in the control group (n = 85), and those with postoperative anxiety or depression were included in the negative emotion group (n = 61). There were notable variations in age, sex, education level, family per capita monthly income, and duration of diabetes (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 1.

| Data | Normal group (n = 85) | Negative emotion group (n = 61) | t/χ2/Z | P value |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 43.27 ± 5.62 | 46.43 ± 6.29 | 3.183 | 0.002 |

| Sex (n) | 6.782 | 0.009 | ||

| Male | 52 | 24 | ||

| Female | 33 | 37 | ||

| Place of residence (n) | 0.038 | 0.846 | ||

| Village | 46 | 34 | ||

| Towns | 39 | 27 | ||

| Marital status (n) | 2.988 | 0.224 | ||

| Unmarried | 5 | 1 | ||

| Married | 67 | 54 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 13 | 6 | ||

| Educational level (n) | 2.460 | 0.014 | ||

| Secondary school and lower | 12 | 16 | ||

| High school or technical secondary school | 46 | 35 | ||

| College and above | 27 | 10 | ||

| Family per capita monthly income (yuan, n) | 3.119 | 0.002 | ||

| < 5000 | 13 | 19 | ||

| 5000-10000 | 40 | 32 | ||

| > 10000 | 32 | 10 | ||

| Diabetes course (years, mean ± SD) | 7.35 ± 1.49 | 9.52 ± 1.70 | 8.201 | < 0.001 |

| Family history of diabetes (n) | 0.049 | 0.824 | ||

| No | 67 | 49 | ||

| Yes | 18 | 12 | ||

| Underlying disease (n) | ||||

| Hypertension | 22 | 24 | 2.982 | 0.084 |

| Hyperlipemia | 16 | 9 | 0.414 | 0.520 |

With anxiety and depression as dependent variables (0 = no, 1 = yes) and age, sex, level of education, family per capita monthly income, and duration of diabetes as independent variables (assignments are shown in Table 2), these variables were incorporated into the logistic regression model. The results indicated that being female, family per capita monthly income of < 5000 yuan, and a longer duration of diabetes were risk factors for negative emotions in patients with DR after vitrectomy (P < 0.05), as indicated in Table 3.

| Age | Original input |

| Sex | 1 = male, 2 = female |

| Educational level | 1 = secondary school and lower, 2 = high school or technical secondary school, 3 = college and beyond |

| Family per capita monthly income | 1 ≤ 5000 yuan, 2 = 5000-10000 yuan, 3 ≥ 10000 yuan |

| Diabetes course | Original input |

| Independent variable | B | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Age | 0.064 | 0.039 | 2.751 | 0.097 | 1.066 | 0.998-1.151 |

| Sex | 1.128 | 0.476 | 5.627 | 0.018 | 3.090 | 1.217-7.847 |

| Educational level | -0.363 | 0.331 | 1.206 | 0.272 | 0.696 | 0.364-1.330 |

| Family per capita monthly income | -1.089 | 0.364 | 8.927 | 0.003 | 0.337 | 0.165-0.688 |

| Diabetes course | 0.959 | 0.184 | 27.043 | < 0.001 | 2.068 | 1.817-3.744 |

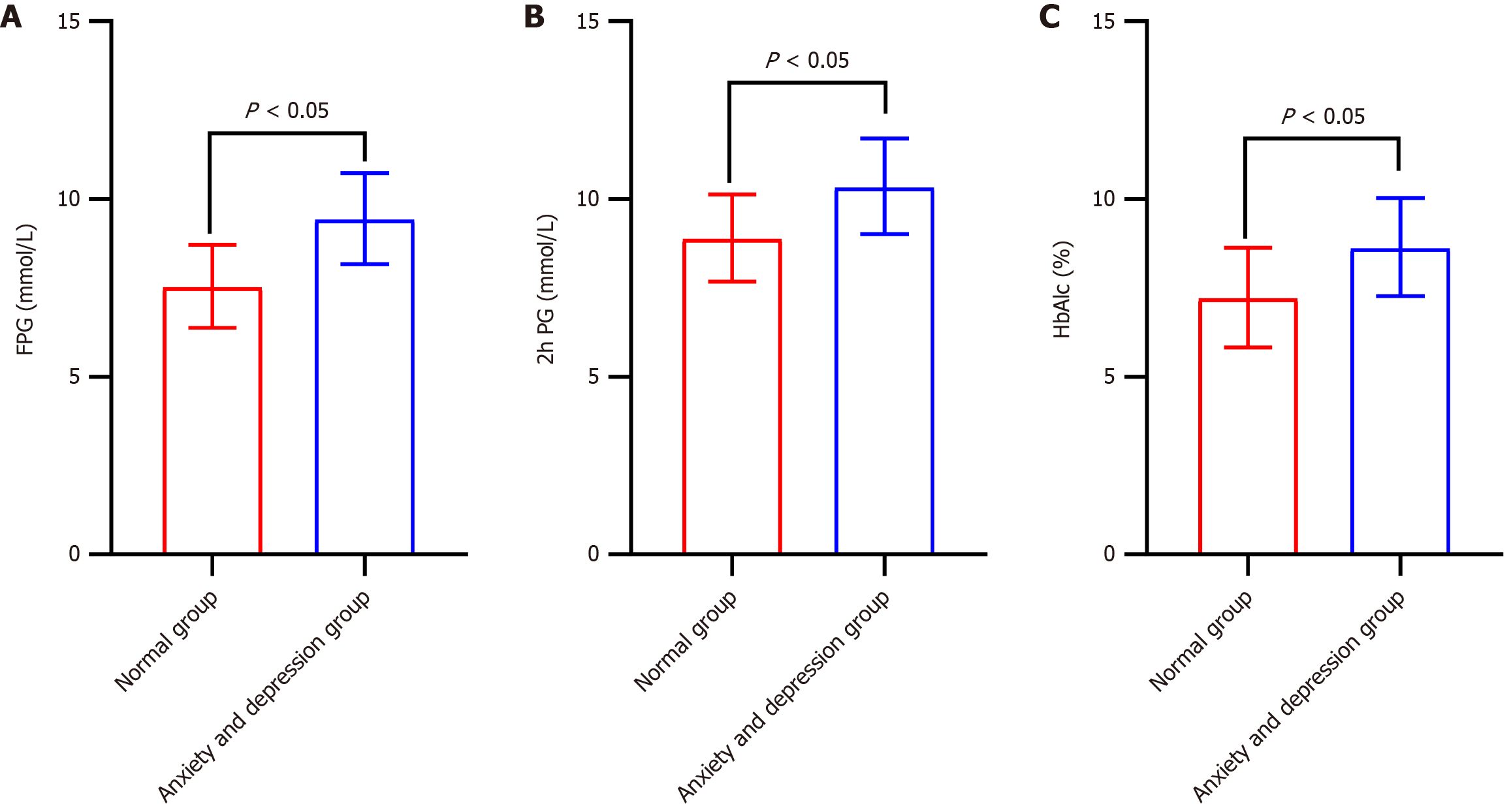

The concentrations of FPG, 2hPG, and HbA1c in the negative emotion group exceeded those in the control group (P < 0.05), as shown in Figure 2. Pearson's correlation coefficients showed that SAS scores were positively associated with FPG, 2hPG, and HbA1c, and SDS scores were positively associated with FPG and 2hPG levels (P < 0.05), as indicated in Table 4.

| FPG | 2hPG | HbA1c | ||||

| r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | |

| SAS | 0.422 | < 0.001 | 0.334 | < 0.001 | 0.362 | < 0.001 |

| SDS | 0.218 | 0.008 | 0.217 | 0.008 | -0.077 | 0.355 |

In the context of the transition from a biomedical model to a medical model that incorporates bio-psycho-social factors, the phenomenon of physical diseases accompanied by psychological problems has attracted widespread attention from medical and psychological circles and patients themselves. Simply treating a disease and ignoring the emotional, psychological, and other aspects of intervention may lead to aggravation or complications, thus affecting the therapeutic effect and prognosis of the disease. Visual decline in patients with DR frequently leads to adverse emotions, including anxiety and depression[9-11]. After vitrectomy, owing to changes in body function, patients do not adapt to a postoperative lifestyle quickly. Simultaneously, the degree of visual recovery varies from person to person. Uncertainty and high expectations cause many patients to bear immense psychological pressure, which further aggravates anxiety and depression symptoms[10].

One study evaluated the impact of standard of living and social support on depression in patients with DR, and approximately 50% of the patients showed moderate, severe, or extreme depression[12]. The findings of this investigation indicated that 41.78% of patients with DR experienced anxiety and depression after vitrectomy, which is quite high. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the risk factors that may make DR patients more susceptible to adverse emotional states, such as feelings of unease and sadness after vitrectomy, to help the clinic better identify potential or existing patients with anxiety and depression and to promote early treatment plans. Logistic regression analysis revealed that being female, family per capita monthly income of < 5000 yuan, and a longer duration of diabetes were risk factors for negative emotions in patients with DR after vitrectomy. We hypothesize that the fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone that occur during the mensural cycle may affect the balance of neurotransmitters in women. These hormonal fluctuations may be exacerbated postoperatively, thereby indirectly affecting mood[13]. Additionally, women often bear multiple stressors in society, such as occupational, family, and social roles, and the pressure from these roles may cause female patients to be more concerned about their health after surgery, thereby increasing their worry and anxiety about the surgical outcome. These factors are intertwined and interdependent rather than independent, and they may be why female DR patients are more prone to negative emotions after vitrectomy.

The high cost of DR treatment places heavy economic pressure on low-income patients. Additionally, low-income patients often lack sufficient social support, and a meta-analysis that included 14 studies[14] found that high social support is negatively correlated with low levels of anxiety. Social support can provide an external coping resource that helps patients better face the challenges and uncertainty of surgery. When social support is insufficient, patients may feel that they are unable to effectively cope with these challenges, which can increase their anxiety levels. When the course of diabetes is long, patients often need to undergo continuous treatment and rehabilitation, and experience uncertainty regarding the disease. Long-term stress and uncertainty may cause patients to feel helpless, depressed, and hopeless, and their long-term disease status means that they may need to deal with various symptoms, side effects, and complications. Simultaneously, they must deal with daily problems related to the disease. This continuous state of fatigue may make patients more susceptible to anxiety and depression. In addition, the longer the course of diabetes, the more severe the retinal damage and visual impairment. Previous studies have shown that visual changes are important factors associated with changes in mental health[15,16]. Visual impairment affects all aspects of daily life, and patients experience distrust in the external environment. Therefore, they avoid communication with the outside world, resulting in self-isolation, which can easily aggravate negative emotions[17]. It is suggested that, during the perioperative period of vitrectomy, more attention and support should be given to female, low-income, and long-term diabetic patients with DR, and their self-cognition and self-worth should be improved through education and publicity to help them establish a positive attitude towards life and their psychological state.

The FPG, 2hPG, and HbA1c concentrations in the negative emotion group exceeded those in the control group. Furthermore, Pearson's correlation coefficient showed that the SAS score was positively associated with FPG, 2hPG and HbA1c, and the SDS score was positively associated with FPG and 2hPG levels, indicating that anxiety and depression could affect the blood glucose control level of patients with DR after vitrectomy to a certain extent. A study investigating the effect of psychological factors on the management of blood sugar levels in pediatric patients diagnosed with type I diabetes found that the HbA1c level in children with greater psychological stress was 1.68 times higher than that in children without stress[18]. Another study showed that high blood glucose levels were associated with anxiety- and depression-related diseases[19]. Anxiety may cause strong psychological stress, activate the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenaline axis, promote the release of catecholamines, cause excessive sympathetic excitement, lead to increased cortisol concentration, and subsequently affect the stability of blood glucose concentration[20]. Simultaneously, the worse the blood glucose control, the more serious the visual impairment, and the more serious the concern for visual loss, the greater the possibility of anxiety and depression. A blood glucose management plan should be developed for post

Despite the contributions of this study, several limitations remain. First, this study used a single-center investigation with a relatively small sample size, which may introduce regional and population selection biases. Future research should consider expanding the sample size and incorporating data from multiple centers to enhance the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. Second, this study focused solely on short-term postoperative negative emotional states without conducting long-term follow-up assessments. Subsequent studies could extend the follow-up duration to track trends in negative emotions and their correlation with disease prognosis. Furthermore, this research did not thoroughly investigate the specific mechanisms underlying negative emotions or their interactions with physiological indicators. Future inquiries might integrate theories and methodologies from neuroscience, psychology, and related fields for a more comprehensive exploration. Finally, this study did not account for other influencing factors, such as pharmacological treatments and social support systems on negative emotional states; future investigations could refine both the collection and analysis of these relevant variables.

The incidence of negative emotions was high in patients with DR after vitrectomy. Sex, income level, and duration of diabetes influenced negative emotions. Negative emotions positively correlated with blood glucose levels. Therefore, targeted prevention and control measures must be formulated for clinical use.

| 1. | Wong TY, Sabanayagam C. Strategies to Tackle the Global Burden of Diabetic Retinopathy: From Epidemiology to Artificial Intelligence. Ophthalmologica. 2020;243:9-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ghamdi AHA. Clinical Predictors of Diabetic Retinopathy Progression; A Systematic Review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2020;16:242-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schreur V, Brouwers J, Van Huet RAC, Smeets S, Phan M, Hoyng CB, de Jong EK, Klevering BJ. Long-term outcomes of vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99:83-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Berrocal MH, Acaba-Berrocal L. Early pars plana vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: update and review of current literature. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021;32:203-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stamenkovic DM, Rancic NK, Latas MB, Neskovic V, Rondovic GM, Wu JD, Cattano D. Preoperative anxiety and implications on postoperative recovery: what can we do to change our history. Minerva Anestesiol. 2018;84:1307-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kühlmann AYR, de Rooij A, Kroese LF, van Dijk M, Hunink MGM, Jeekel J. Meta-analysis evaluating music interventions for anxiety and pain in surgery. Br J Surg. 2018;105:773-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Wilkinson CP, Ferris FL 3rd, Klein RE, Lee PP, Agardh CD, Davis M, Dills D, Kampik A, Pararajasegaram R, Verdaguer JT; Global Diabetic Retinopathy Project Group. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1677-1682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1980] [Cited by in RCA: 2287] [Article Influence: 104.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bao J, Wang XY, Chen CH, Zou LT. Relationship between primary caregivers' social support function, anxiety, and depression after interventional therapy for acute myocardial infarction patients. World J Psychiatry. 2023;13:919-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xu L, Chen S, Xu K, Wang Y, Zhang H, Wang L, He W. Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety among Chinese diabetic retinopathy patients: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0267848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang B, Wang Q, Zhang X, Jiang L, Li L, Liu B. Association between self-care agency and depression and anxiety in patients with diabetic retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bloom JM, Mason JO 3rd, Mason L, Swain TA. Fears, Depression, and Anxieties of Patients With Diabetic Retinopathy and Implications for Education and Treatment. J Vitreoretin Dis. 2020;4:484-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Abu Ameerh MA, Hamad GI. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and related risk factors among diabetic patients with retinopathy attending the Jordan University Hospital. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31:529-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li X, Zhang W, Pan Z, Shen R. Cohort analysis of relevant factors for negative emotions during the perioperative period in choledocholithiasis patients treated with ERCP and the impact on prognosis. Gland Surg. 2023;12:651-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kok XLF, Newton JT, Jones EM, Cunningham SJ. Social support and pre-operative anxiety in patients undergoing elective surgical procedures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Psychol. 2023;28:309-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Frank CR, Xiang X, Stagg BC, Ehrlich JR. Longitudinal Associations of Self-reported Vision Impairment With Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Among Older Adults in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:793-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ekemiri KK, Botchway EN, Ezinne NE, Sirju N, Persad T, Masemola HC, Chidarikire S, Ekemiri CC, Osuagwu UL. Comparative Analysis of Health- and Vision-Related Quality of Life Measures among Trinidadians with Low Vision and Normal Vision-A Cross-Sectional Matched Sample Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Abou-Hanna JJ, Leggett AN, Andrews CA, Ehrlich JR. Vision impairment and depression among older adults in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36:64-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Andrade CJDN, Alves CAD. Influence of socioeconomic and psychological factors in glycemic control in young children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:48-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chourpiliadis C, Zeng Y, Lovik A, Wei D, Valdimarsdóttir U, Song H, Hammar N, Fang F. Metabolic Profile and Long-Term Risk of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress-Related Disorders. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e244525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hilliard ME, Yi-Frazier JP, Hessler D, Butler AM, Anderson BJ, Jaser S. Stress and A1c Among People with Diabetes Across the Lifespan. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |