Published online Aug 19, 2023. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v13.i8.551

Peer-review started: January 22, 2023

First decision: March 1, 2023

Revised: March 10, 2023

Accepted: May 5, 2023

Article in press: May 5, 2023

Published online: August 19, 2023

Processing time: 206 Days and 13.9 Hours

Behavioral activation therapy (BA) is as effective as cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) in treating depression and can be delivered by practitioners with much less psychological training, making it particularly suitable for low resource settings. BA that is culturally adapted for Muslims (BA-M) is a culturally adapted form of BA that has been found acceptable and feasible for Muslims with depression in the United Kingdom and Turkey; however, this is the first time that its efficacy has been determined through a definitive randomized controlled trial.

To compare the effectiveness of BA-M with CBT for Muslim patients with depression in Pakistan.

One hundred and eight patients were randomized 1:1 to treatment arms in a parallel-group randomized controlled trial in hospital or community sites in Lahore, Pakistan. Recruitment followed self-referral or referrals from clinicians, consultants or relevant professionals at each site. Four measures were recorded by blinded assessors: The patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9); the BA for depression scale short form (BADS-SF); symptom checklist-revised and the World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Brief Scale. All measures were recorded at baseline and post treatment; PHQ-9 and BADS-SF were also recorded at each session and at three month follow up. The primary analysis was to regress the PHQ-9 score after therapy upon the PHQ-9 score before therapy (baseline) and the type of therapy given, that is, analysis of covariance. In addition, analysis using PHQ-9 scores collected at each therapy session was employed in a 2-level regression model.

Patients in the BA-M arm experienced greater improvement in PHQ-9 score of 1.95 units compared to the CBT arm after adjusting for baseline values (P = 0.006) The key reason behind this improvement was that patients were retained in therapy longer under BA-M, in which patients were retained for an average 0.75 sessions more than CBT patients (P = 0.013). Patients also showed significant differences on physical (P < 0.001), psychological (P = 0.004) and social (P = 0.047) domains of Quality of Life (QoL) at post treatment level, indicating an increased QoL in the BA-M group as compared to the treatment as usual group. Some baseline differences were noted in both groups for BA scores and two domains of QoL scale: Physical and environment, which might have influenced the results, though the BA-M group showed more improvement at completion of therapy.

Results proved the efficacy of BA-M in reducing symptoms for depressed patients in Pakistan, indicating BA-M is a promising treatment modality for depression in future, particularly in low resource settings.

Core Tip: Behavioral activation therapy that is culturally adapted for Muslims (BA-M) is a more effective treatment for depression in comparison to cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for Muslim populations within the Pakistani cultural context. Increased engagement with the therapy appears to be the key reason for the significantly lower depression scores of patients receiving BA-M. As this treatment can be delivered by practitioners with much less psychological training than CBT, it is particularly suitable for Muslim patients in low resource settings.

- Citation: Dawood S, Mir G, West RM. Randomized control trial of a culturally adapted behavioral activation therapy for Muslim patients with depression in Pakistan. World J Psychiatry 2023; 13(8): 551-562

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v13/i8/551.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v13.i8.551

Depression is a mood disorder with widespread occurrence throughout the world[1,2], affecting more than 300 million people around the globe according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. It is ranked as the largest cause of disability worldwide, with more than 4% global prevalence and an upward trend in developing countries, with almost half of cases occurring in South-East Asia[3]. In Pakistan, the risk of developing depression is 10%-25% higher for women than for men and this can be further increased by infertility[4], having a disabled child, emotional setbacks or family issues and disputes[5]. Depression can have a strong impact on family members as well as on the individual with depression[6]. Recorded rates of prevalence for maternal depression in Pakistan are among the highest globally at 28%–36%[7,8] and children of depressed mothers in this context are at an increased risk of being underweight, having poor health with more frequent episodes of diarrhea compared to the children of non-depressed mothers[8,9]. A strong relationship between infertility and psychological comorbidities has also been found[10] and evidence suggests that poverty is strongly linked with depression with almost 50% of low income mothers likely to be depressed[11]. This evidence highlights the need for a cost-effective treatment for depression in Pakistan. Interventions are needed to increase access to treatment and reduce the personal as well as social costs of depression, including impact on daily life, upbringing of children and loss in productivity, such as time taken off from work[12].

Despite the availability of a number of evidence-based therapies for depression, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), behavioral activation (BA), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and exposure-based therapy[13-15], there is a growing body of empirical evidence about the need for, and effectiveness of, culturally adapted and religion-sensitive therapies[16]. Literature in this area shows that interventions that focus on culture and faith can effectively reduce depression and improve quality of life (QoL)[17,18]. Sensitivity to religious beliefs as a resource for health has been integrated into therapies such as CBT[17,19,20]; counseling[21,22]; ACT[23]; and trauma related therapies[24]. Integrating religious coping in adapted versions of such therapies has proved as effective as existing treatments and faith-adapted therapies have shown more positive results in the management of depressive symptoms in Muslim clients[25,26].

BA that is culturally adapted for Muslims (BA-M), developed for United Kingdom-based Muslim communities, is a successful faith-sensitive adaptation of an existing psychological treatment[27,28]. BA-M therapy is based on BA, an existing evidence-based psychosocial treatment for depression that focuses on clients’ values and links these with behavioral goals[29-31]. Piloting of this adapted version has shown that BA-M was feasible within a United Kingdom healthcare setting and was very positively received by Muslim clients[28]. The inclusion of ‘client values’ in therapy makes BA a particularly suitable treatment for adaptation to diverse cultural needs and it has been successfully adapted and tailored to multiple cultural contexts across the globe[32-34]. The present research is the first study globally to assess the efficacy of BA-M through a randomized controlled trial with adult depressed patients. The trial was conducted in Pakistan, a low income setting in which the approach was considered relevant for the majority of the population.

A three-center two-arm parallel block-randomized controlled trial was conducted to estimate the effectiveness of BA-M to treat depression in Pakistan compared to treatment as usual (TAU) using a 1:1 allocation ratio. Patients were allocated at each center in blocks of two with one being randomized to TAU and the other allocated to treatment by BA-M (BA culturally adapted to Muslim faith). There were no changes to the recruitment procedure or methods during the trial. The trial was registered with ISRCTN. Ethical approval was granted by the Faculty of Medicine and Health Ethics Committee at the University of Leeds and the National Bioethics Committee, Pakistan.

Patients with depression were recruited from outpatient departments of three targeted data sites in Lahore, Pakistan: Mayo Hospital (Mayo), Punjab Institute of Mental Health (PIMH) and the Centre for Clinical Psychology, University of the Punjab, Lahore (CCP). Recruitment followed self-referral or referrals from clinicians, consultants or relevant professionals at each site. All patients were over 18 years of age.

An Urdu version of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to screen for depression[35] alongside the symptom checklist-revised (SCL-R) - an indigenous screening tool for which psychometric properties are well established[36]. Patients were invited to take part in the trial if their depression score on PHQ-9 was at least 10 and if they had no comorbid psychological disorders, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, could understand the study measures and could give informed consent.

Patients were randomized to receive either TAU, which was CBT at each site, or BA, adapted to meet the needs of Muslims patients (BA-M). TAU comprised of 8 sessions of CBT.

BA-M is a culturally tailored version of BA, an existing evidence-based psychosocial treatment for depression, which is as effective as CBT but requires less practitioner training[37]. BA-M comprises 6–12 sessions of treatment involving a values assessment. Muslim clients who select religion as a personal value during this assessment are offered the choice of using a self-help booklet designed to help their recovery[27]. The booklet draws on Islamic religious teachings to promote therapeutic goals and ‘positive religious coping’ that supports resilience, hopefulness and self-esteem[38]. Patients were treated in outpatient clinics at the three sites following referrals to clinical psychologists involved in delivering the intervention for the trial.

A demographic information sheet with details of age, gender, education, birth order, family income and type, psychological illness, physical illness, current diagnosis and history of treatment related to psychological issues was administered to each recruited patient. The primary outcome, on which the trial was powered, was the change in PHQ-9 score following therapy, that is, the difference between the PHQ-9 score after therapy and that recorded before therapy commenced. The PHQ-9 measure was used to assess depression and determined the extent to which patients had experienced depressive symptoms over the previous two weeks. The nine items were rated on a 0-3 scale ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘nearly every day’. The PHQ-9 has adequate construct validity and sensitivity to change[39]. In the present study, the Urdu translated version of PHQ-9 was used[7].

There were several secondary outcomes collected to provide greater understanding of the performance of BA-M as a therapy. PHQ-9 was collected not just at baseline and at the end of treatment but at the start of every therapy session. Two other measures were collected before and after therapy. The 9-item BA for depression scale short form (BADS-SF) was used to track activation, including when and how clients became activated during the course of treatment. This measure was developed to improve the original BADS measure and has stronger psychometric properties[40]. The SCL-R[36] is an indigenous checklist which assesses six psychopathologies: Depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, somatization, schizophrenia and low frustration tolerance. In the present study, the subscale of depression with 24 items was used to assess the degree of depression in depressed patients. The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale and psychometric properties are well established for all subscales of SCL-R. A fourth measure, the WHO QoL Brief Scale (WHOQOL-BREF)[41], developed by the WHO with 26 items, was used to assess QoL in depressed patients. This covers 4 major domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships and environment. One item from each of the 24 facets contained in the WHOQOL-100 was included along with two items from the overall QoL and the general health facets. A further outcome measure was the number of sessions attended by each patient to assess patient engagement with therapy.

Power calculations for the sample were based on change in PHQ-9 from baseline (PHQ-9-0) to 3 mo after therapy (PHQ-9-3). Drawing on earlier research, we anticipated that PHQ-9 would have a standard deviation of 5 units and that the correlation between before and after measurements would be 0.75. Consequently, we anticipated that the difference between PHQ-9-3 and PHQ-9-0 would have a standard deviation of 3.54 units[42]. A minimal clinically important difference in PHQ scores was considered to be 2 units on PHQ-9. Using a two-sample t-test to assess the difference between the groups, with 5% significance level, the number required to achieve 80% power is 50 patients per group. It was anticipated that around 15% patients would drop out of the trial before the completion of therapy. Adjusting for drop out thus yielded a sample size of 59 patients per group.

At each site, patients were recruited in pairs by a blind assessor who screened for depression and assigned individuals from each pair at random (using a Microsoft Excel random number generator value below 0.5) to TAU or BA-M. This ensured a random sample balanced for each site and for therapy. It was not possible to conceal the randomization from either the patient or those delivering therapy.

The primary analysis was to regress the PHQ-9 score after therapy upon the PHQ-9 score before therapy (baseline) and the type of therapy given. This analysis of covariance approach was considered to be the optimum statistical method for the analysis of continuous outcomes of randomized control trials (RCTs) where baseline measurements are available[43].

Analysis was undertaken on a complete case basis and the implication for bias due to drop out was considered through analysis of the secondary outcomes. It was not appropriate to assume that data was missing at random since patients may have withdrawn from the trial or from therapy because they were either dissatisfied with their progress through therapy or improved so much that they considered that therapy was no longer required. Hence imputation methods which are valid under the assumption of missing at random were not appropriate here.

As a secondary analysis of PHQ-9, all of the measurements made were considered in a two- level regression analysis with measurements nested within patients by the inclusion of a random intercept for patient. This provided the average change in score per session for each of the two therapies. A Wald test for the interaction term made it possible to formally test if there was a difference in therapy per session.

The average number of sessions attended for each arm was compared with a two-sample t-test to explore the duration of the therapy in each arm. Other secondary outcomes, namely BADS-SF, the total SCL-R score, and the four domains of WHOQOL-BREF were compared with analysis of covariance, as for the primary analysis of PHQ-9.

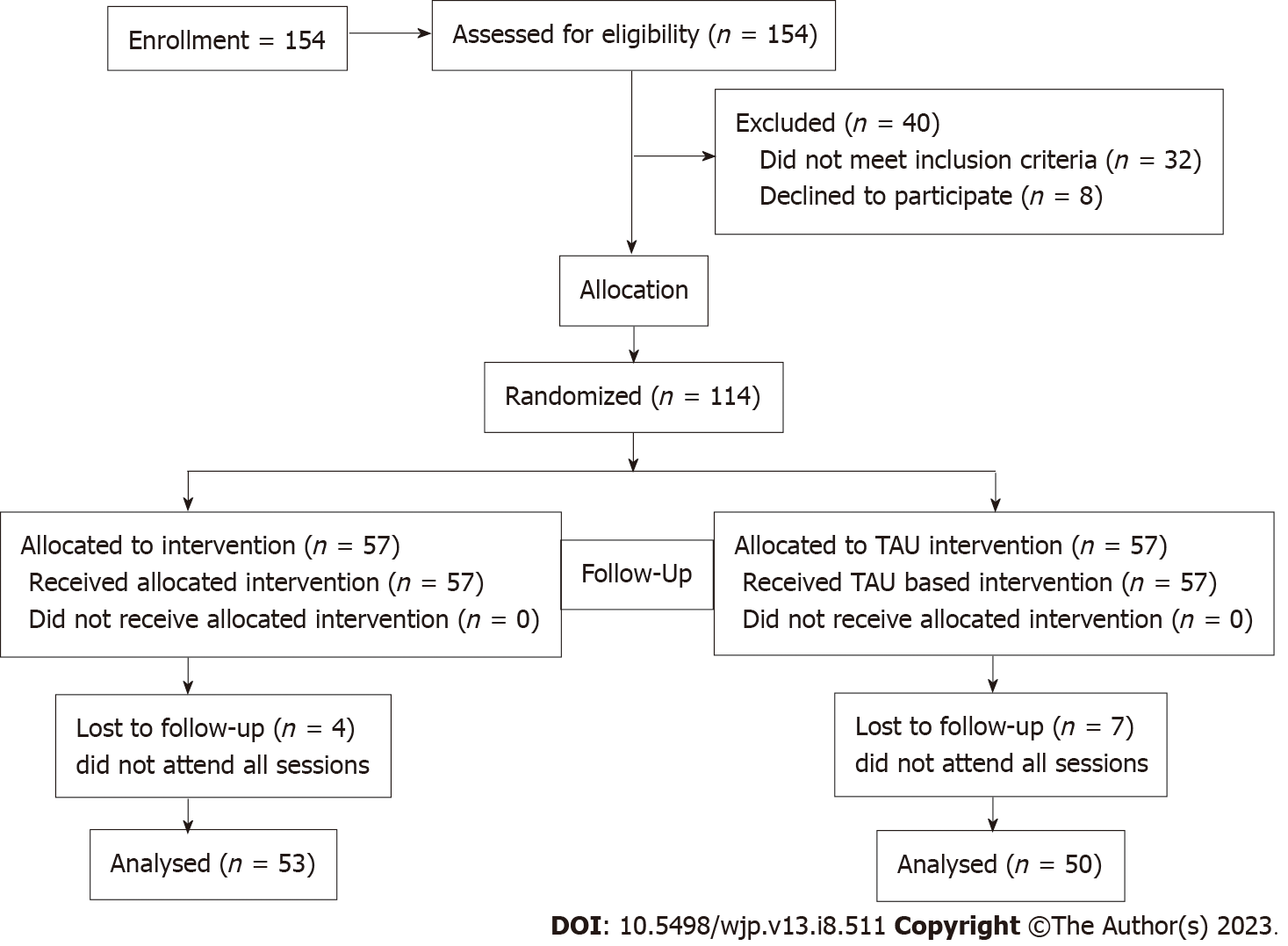

For each group, TAU and BA-M, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment and were analyzed for the primary outcome, namely change in PHQ-9 after treatment, is shown in Figure 1.

The first patient was recruited in March 2020 and recruitment continued until at least 59 patients completed their therapy in each arm. Recruitment was then closed in August 2021, having established that at least 50 patients had been recruited and retained until the end of therapy.

Characteristics between the two groups were similar (Table 1) apart from the initial BADS-SF score and the initial values of the D2 (psychological health) and D4 (environment) domains of WHOQOL-BREF. Analysis methods were designed to adjust for these baseline imbalances.

| Characteristics | BA-M | TAU | P value | |||

| Mean or count | SD or % | Mean or count | SD or % | |||

| Age | 32.3 | 9.6 | 33.8 | 11.5 | 0.437 | |

| Gender | Men | 17 | 30% | 24 | 42% | 0.242 |

| Women | 40 | 70% | 33 | 58% | ||

| Data site | CCP | 18 | 34% | 22 | 39% | 0.880 |

| PIMH | 21 | 40% | 21 | 37% | ||

| Mayo | 14 | 26% | 14 | 25% | ||

| Education | Below primary | 6 | 11% | 6 | 11% | 0.300 |

| Matric | 11 | 20% | 14 | 25% | ||

| FA/A Level | 9 | 16% | 12 | 21% | ||

| Other | 24 | 43% | 14 | 25% | ||

| Middle/secondary | 6 | 11% | 11 | 19% | ||

| Marital status | Married | 27 | 47% | 19 | 33% | 0.039 |

| Sep/divorced/widowed | 5 | 9% | 15 | 26% | ||

| Unmarried | 25 | 44% | 23 | 40% | ||

| Family system | Nuclear | 32 | 56% | 31 | 54% | 0.999 |

| Joint | 25 | 44% | 26 | 46% | ||

| Working status | Yes | 25 | 45% | 21 | 37% | 0.514 |

| No | 31 | 55% | 36 | 63% | ||

| SES | Lower class | 14 | 25% | 21 | 37% | 0.247 |

| Middle or upper class | 42 | 75% | 36 | 63% | ||

| PHQ (Pre) | 19.5 | 4.9 | 20.1 | 4.1 | 0.487 | |

| BADS (Pre) | 20.2 | 8.4 | 15.6 | 6.3 | 0.001 | |

| SCL-R (Dep) | 41.9 | 9.9 | 43.1 | 8.2 | 0.506 | |

| D1 (Pre) | Physical health | 17.9 | 4.9 | 14.7 | 4.8 | 0.001 |

| D2 (Pre) | Psychological health | 12.3 | 3.3 | 11.7 | 3.3 | 0.333 |

| D3 (Pre) | Social relationships | 8.4 | 2.6 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 0.298 |

| D4 (Pre) | Environment | 22.4 | 5.2 | 20.0 | 5.1 | 0.014 |

Seven of 57 patients assigned to TAU and 4 of 57 patients assigned to BA-M withdrew from the trial. Data after baseline collection was not available for analysis for these patients. Table 2 shows the characteristics of patients who were lost to follow up compared to those who were retained.

| Characteristics | Lost to follow up (n = 11) | Retained (n = 103) | P value | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 35.27 (13.94) | 32.83 (10.19) | 0.469 | |

| Gender | Men | 9 (82%) | 32 (31%) | 0.003 |

| Women | 2 (18%) | 71 (69%) | ||

| Education | Below primary | 1 (10%) | 11 (11%) | |

| Matric | 3 (30%) | 22 (21%) | ||

| FA/A Level | 1 (10%) | 20 (19%) | 0.915 | |

| Other | 3 (30%) | 35 (34%) | ||

| Middle/secondary | 2 (20%) | 15 (15%) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 3 (27%) | 43 (42%) | 0.617 |

| Sep/divorced/widowed | 2 (18%) | 18 (18%) | ||

| Unmarried | 6 (55%) | 42 (41%) | ||

| Family system | Nuclear | 10 (91%) | 53 (52%) | 0.029 |

| Joint | 1 (9%) | 50 (49%) | ||

| Working status | Yes | 5 (46%) | 41 (40%) | 0.989 |

| No | 6 (55%) | 61 (60%) | ||

| SES | Lower class | 6 (55%) | 29 (28%) | 0.151 |

| Middle or upper class | 5 (46%) | 73 (72%) | ||

| PHQ Pre | 20.18 (2.82) | 19.79 (4.71) | 0.786 | |

| BADS Pre | 14.09 (4.11) | 18.34 (7.90) | 0.082 | |

| SCL-R (Dep) | 36.91 (9.61) | 43.14 (8.88) | 0.030 | |

| D1 (Pre) | Physical health | 16.64 (2.94) | 16.33 (5.26) | 0.850 |

| D2 (Pre) | Psychological health | 12.18 (3.06) | 11.94 (3.31) | 0.818 |

| D3 (Pre) | Social relationships | 8.00 (1.41) | 8.17 (2.70) | 0.842 |

| D4 (Pre) | Environment | 20.18 (3.06) | 21.31 (5.44) | 0.501 |

Male patients and those in nuclear families were seen to be more susceptible to drop out. Feedback from therapists indicated that therapy sessions during working hours were more likely to adversely affect attendance by men and the average baseline SCL-R value was also lower among drop outs, indicating less severe depressive symptoms in this group. Data for 50 TAU patients and 53 BA-M patients was available for analysis.

A summary of the outcome variables after therapy is provided in Table 3. This provides unadjusted t-test comparisons of the outcomes between groups. Significant post treatment differences in depression (P = 0.006) and QoL scores were found in the BA group compared to TAU following completion of treatment.

| Characteristics | BA-M | TAU | P value |

| n | 57 | 57 | |

| Drop Out | 4 (7%) | 7 (12%) | 0.526 |

| Retained | 53 (93%) | 50 (88%) | |

| PHQ (Post), mean (SD) | 4.19 (3.42) | 6.18 (3.85) | 0.006 |

| BADS (Post) | 34.34 (7.32) | 27.90 (8.53) | < 0.001 |

| SCL-R (Dep) | 16.00 (8.08) | 19.96 (7.74) | 0.013 |

| D1 Physical Health (Post) | 25.85 (2.91) | 22.84 (3.35) | < 0.001 |

| D2 Psychological Health (Post) | 19.74 (3.08) | 17.88 (3.26) | 0.004 |

| D3 Social Relationships (Post) | 10.45 (1.96) | 9.64 (2.15) | 0.047 |

| D4 Environment (Post) | 27.83 (4.91) | 26.48 (4.44) | 0.147 |

| Number of Sessions | 9.00 (1.77) | 8.25 (1.39) | 0.013 |

The primary outcome (PHQ-9) was also regressed upon baseline values and therapy arm and the table of regression coefficients is given in Table 4.

| Characteristics | Estimate | 95%CI | P value |

| Intercept | 1.205 | (-1.887, 4.298) | 0.441 |

| TAU Arm | 1.946 | (0.545, 3.347) | 0.007 |

| Baseline PHQ | 0.152 | (0.002, 0.301) | 0.046 |

From the coefficients in Table 4, it is seen that generally those in the TAU arm have higher PHQ-9 scores after therapy and that an adjustment for baseline values of PHQ-9 is important since the coefficient is statistically significant at the 5% level. Plots of residuals (not shown due to space limitations) were seen as satisfactory. The interpretation for this trial based on the primary analysis is that BA-M is associated with a greater reduction in depression symptoms as measured by PHQ-9 after completion of therapy.

The analysis of secondary outcomes BADS-SF and SCL-R are summarized in Table 5.

| Characteristics | Estimate | 95%CI | P value |

| BADS | |||

| Intercept | 36.332 | (31.629, 41.035) | < 0.001 |

| Arm TAU | -6.854 | (-10.076, -3.631) | < 0.001 |

| Baseline BADS | -0.098 | (-0.302, 0.107) | 0.346 |

| SCL-R (Dep) | |||

| Intercept | 0.455 | (-6.723, 7.633) | 0.900 |

| Arm TAU | 3.802 | (0.960, 6.644) | 0.009 |

| Baseline SCL-R (Dep) | -0.098 | (-0.302, 0.107) | 0.346 |

| WHOQOL (D1: Physical) | |||

| Intercept | 22.948 | (20.662, 25.235) | < 0.001 |

| Arm TAU | -2.489 | (-3.737, -1.241) | < 0.001 |

| Baseline (D1: Physical) | 0.162 | (0.043, 0.281) | 0.008 |

| WHOQOL (D2: Psychological) | |||

| Intercept | 16.097 | (13.71, 25.235) | < 0.001 |

| Arm TAU | -1.614 | (-2.809, -0.420) | 0.009 |

| Baseline (D2: Psychological) | 0.295 | (0.133, 0.476) | 0.002 |

| WHOQOL (D3: Social) | |||

| Intercept | 7.836 | (6.583, 9.089) | < 0.001 |

| Arm TAU | -0.688 | (-1.424, 0.048) | 0.066 |

| Baseline (D3: Social) | 0.313 | (0.176, 0.450) | < 0.001 |

| WHOQOL (D4: Environment) | |||

| Intercept | 18.072 | (14.496, 21.648) | < 0.001 |

| Arm TAU | -0.328 | (-1.967, 1.312) | 0.693 |

| Baseline (D4: Environment) | 0.435 | (0.283, 0.586) | < 0.001 |

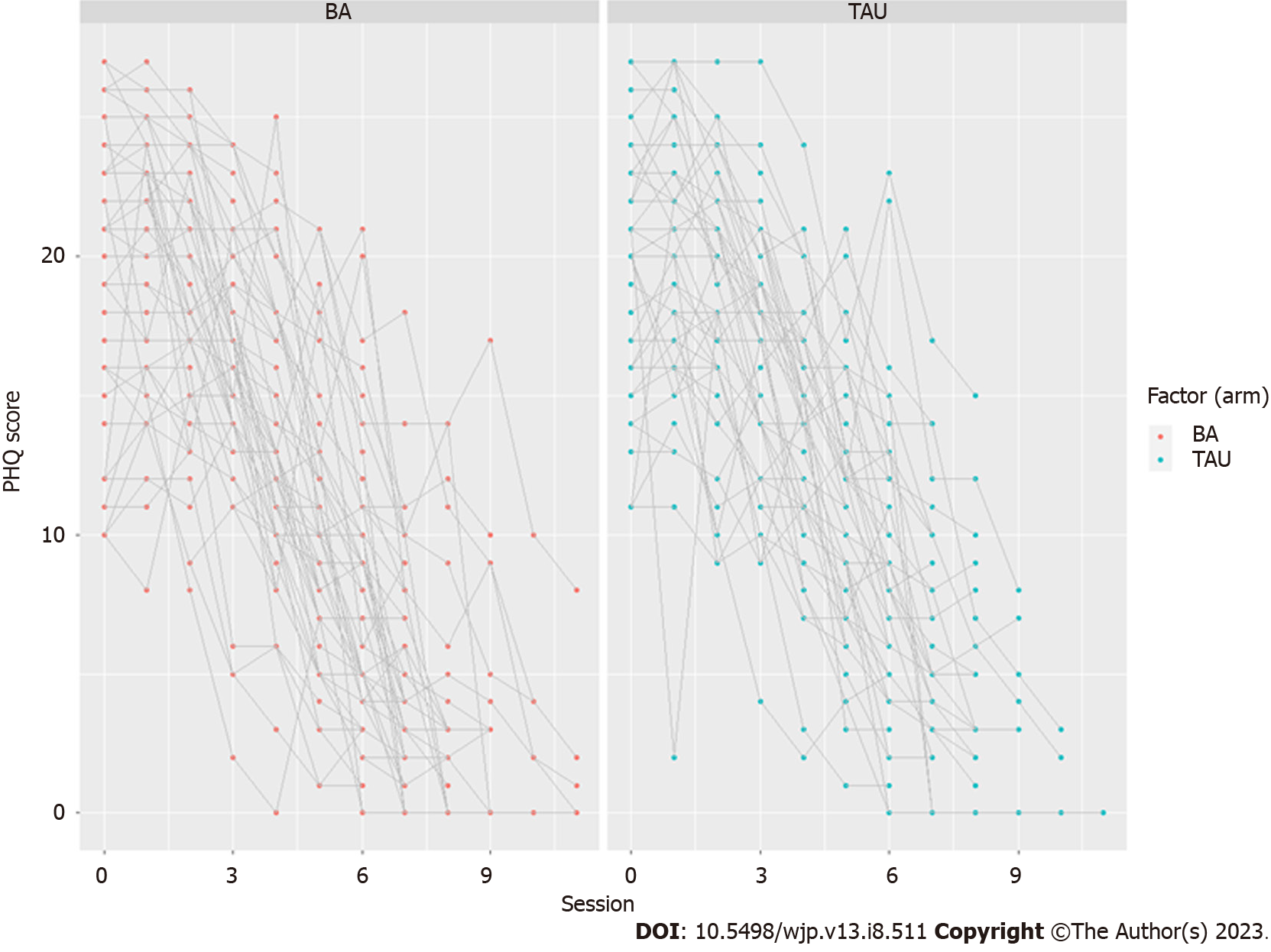

As the PHQ-9 tool was used at every therapy session, more detailed longitudinal data was available. Values are plotted in Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows that the PHQ-9 trajectories might be simply modeled with a linear decrease by session. This was undertaken with a linear mixed effects model with a random intercept for patient. The coefficients are shown in Table 6.

| Characteristics | Estimate | 95%CI | P value |

| Overall Intercept | 21.536 | (20.549, 22.524) | < 0.001 |

| TAU Arm | 0.396 | (-1.010, 1.800) | 0.582 |

| Session | -2.260 | (-2.363, -2.156) | < 0.001 |

| TAU-session interaction | 0.10203 | (-0.058, 0.261) | 0.210 |

The results revealed that the interpretation of the coefficients in Table 6 showed a decline in PHQ-9 of 2.26 points on average for every session attended and there is little evidence of BA-M being superior to TAU on this basis. The reason behind the statistically significant improvement due to BA-M therapy rather than TAU, as seen in the analysis of primary outcome, is that patients under BA-M are retained in therapy longer. Table 3 also shows that the mean number of sessions attended increases from 8.25 under TAU to 9.00 under BA-M (P = 0.013).

This is the first trial evaluation of the BA-M culturally adapted therapy for depression globally. Previous evaluations have shown feasibility and acceptability to therapists and patients in both United Kingdom[27] and Turkish settings[44]. Findings confirm the importance of culturally adapted approaches when delivering mental health therapies developed in Western contexts to non-Western populations[16] and the benefits of faith-sensitive approaches in general[25]. The results of the current study support the efficacy of BA-M therapy in line with the wider literature on BA as a cost-effective and efficacious alternative to CBT[45]. Patients in the BA-M group showed lower levels of depression (PHQ-9 and SCL-R) and higher scores of BA (BADS-SF) post treatment, indicating the effectiveness of BA-M therapy in reducing depression and increasing helpful activity in patients. Patients also showed significant differences on physical (P < 0.001), psychological (P = 0.004) and social (P = 0.047) domains of QoL at post treatment level, indicating an increased QoL in the BA-M group as compared to the TAU group.

Fewer patients dropped out of the BA-M group than from the TAU group and this was seen to lead to greater benefit since the improvement in symptoms per session was consistent throughout the usual therapy period of 8 wk. Patients who dropped out tended to have low scores on the depression scale as compared to those who were retained. The results also showed that men and those who were living in nuclear families were found to be more susceptible to drop out.

The particular benefits of BA-M appear to have been achieved as a result of patient retention in therapy and this is an important factor in recovery from depression. As in the United Kingdom study for BA-M[27], the faith-sensitive approach appears to have a motivating influence on patients. Qualitative findings from the United Kingdom study indicated that most patients were enthusiastic about and motivated by the engagement with religious identity in this approach. This was designed to support ‘positive religious coping’ that increased resilience, hope and self-esteem[38]. The findings confirm previous research, both on value-based practice that takes account of cultural context and on BA, which particularly focuses on increasing activities that are linked to an individual’s values and reward systems, consequently enhancing their behavioral patterns and reducing depressive symptoms[46,47].

We note there were important baseline differences in both groups for BA scores and two domains of QoL scale: Physical and Environment. The BA-M group showed more BA and QoL related to physical health and environment as compared to the TAU group. These may have influenced findings although it is clear that there was greater improvement in physical, psychological and social QoL domains for the BA-M group at completion of treatment.

There were also gender differences in retained and dropped out patients as 82% of dropped out patients were men. Differences in the family system of patients were also apparent as 91% of dropped out patients were from nuclear families.

In conclusion, this RCT demonstrated the benefit of BA-M, a culturally adapted form of BA, over usual treatment (CBT) at the end of therapy. It is clear that both CBT and BA-M are successful therapies for reducing depression, however, findings suggest that the additional benefit of BA-M is due to greater retention of participants in therapy that is likely to be due to the cultural adaptation. The trial confirms existing evidence on the benefits of therapy that supports activation of religious behaviors as a resource for health and fulfills the need for rigorous research in a population sample that has hitherto been underrepresented and for whom such behaviors may be critical to treatment outcomes[48].

Depression is the largest cause of disability worldwide and can strongly impact on families and society as well as individuals. Culturally appropriate, accessible and cost-effective treatments are needed in low resource settings such as Pakistan. This study is the first randomized control trial globally of behavioral activation (BA) therapy that is culturally adapted for Muslim patients (BA-M).

The main focus was to explore whether BA-M, as a culturally adapted therapy, would achieve better results than cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), a standard treatment developed in a Western context. BA can be delivered by practitioners with much less psychological training than CBT, making it particularly suitable for low resource settings. This research has great significance for future studies on how to reduce depression and increase access to treatment for Muslim communities worldwide.

The purpose of the study was to compare the effectiveness of BA-M with CBT for Muslim patients in Pakistan.

Clinical data were analyzed for 108 patients in a parallel-group randomized controlled trial in hospital or community sites in Lahore, Pakistan. Four measures were recorded by blinded assessors: The patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9); the BA for depression scale short form (BADS-SF); symptom checklist-revised and the WHOQOL-BREF quality of life (QoL) scale. All measures were recorded at baseline and post treatment; PHQ-9 and BADS-SF were also recorded at each session and at three month follow up. The primary analysis was to regress the PHQ-9 score after therapy upon the PHQ-9 score before therapy (baseline) and the type of therapy given. In addition, analysis using PHQ-9 scores collected at each therapy session was employed in a 2-level regression model.

Patients in the BA-M arm experienced greater improvement in PHQ-9 score compared to the CBT arm and were retained in therapy longer than those receiving CBT after adjusting for baseline values. BA-M patients also showed significant differences on physical, psychological and social domains of QoL at post treatment level, indicating an increased QoL in the BA-M group as compared to the CBT group.

BA-M is a culturally appropriate treatment for depression that achieves better results than CBT, which is current standard treatment in Pakistan. BA-M can be delivered by practitioners with much less psychological training than CBT and is a promising treatment modality for depression in Muslim communities, particularly in low resource settings.

Future research should evaluate acceptability and effectiveness of BA-M in other Muslim populations, including where these constitute minorities, and issues related to implementation and scale-up.

The researchers gratefully acknowledge the contribution of participants, blind reviewers and therapists at data sites.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Pakistan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dimopoulos N, Greece; Stoyanov D, Bulgaria S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li L

| 1. | Miller WR, Seligman ME. Depression and the perception of reinforcement. J Abnorm Psychol. 1973;82:62-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rehm J, Shield KD. Global Burden of Disease and the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 724] [Article Influence: 120.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. 2017. [cited 3 Apr 2023]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Yusuf L. Depression, anxiety and stress among female patients of infertility; A case control study. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32:1340-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Azeem MW, Dogar IA, Shah S, Cheema MA, Asmat A, Akbar M, Kousar S, Haider II. Anxiety and Depression among Parents of Children with Intellectual Disability in Pakistan. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22:290-295. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Smit HFE. Prevention of depression. Doctoral Dissertation, Vrije University Amsterdam. 2007. [cited 3 Apr 2023]. Available from: https://research.vu.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/42176026/complete+dissertation.pdf. |

| 7. | Husain N, Bevc I, Husain M, Chaudhry IB, Atif N, Rahman A. Prevalence and social correlates of postnatal depression in a low income country. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9:197-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:902-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 627] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Saeed H, Saleem Z, Ashraf M, Razzaq N, Akhtar K, Maryam A, Abbas N, Akhtar A, Fatima N, Khan K, Rasool L. Determinants of anxiety and depression among university students of Lahore. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2018;16:1283-1298. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abbasi S, Kousar R, Sadiq SS. Depression and anxiety in Pakistani infertile women. J Surg Pak 2016; 21, 13-17. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Knitzer J, Theberge S, Johnson K. Reducing maternal depression and its impact on young children: Toward a responsive early childhood policy framework. 2008. [cited 3 Apr 2023]. Available from: https://www.nccp.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/text_791.pdf. |

| 12. | Mental Health Foundation. Fundamental facts about mental health. 2016. [cited 3 Apr 2023]. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/The-Fundamental-facts-about-mental-health-2016.pdf. |

| 13. | Grosse Holtforth M, Krieger T, Zimmermann J, Altenstein-Yamanaka D, Dörig N, Meisch L, Hayes AM. A randomized-controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression with integrated techniques from emotion-focused and exposure therapies. Psychother Res. 2019;29:30-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hynninen MJ, Bjerke N, Pallesen S, Bakke PS, Nordhus IH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in COPD. Respir Med. 2010;104:986-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cuijpers P, Quero S, Dowrick C, Arroll B. Psychological Treatment of Depression in Primary Care: Recent Developments. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Anik E, West RM, Cardno AG, Mir G. Culturally adapted psychotherapies for depressed adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:296-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Burton WN, Conti DJ. Depression in the workplace: the role of the corporate medical director. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:476-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee YY, Barendregt JJ, Stockings EA, Ferrari AJ, Whiteford HA, Patton GA, Mihalopoulos C. The population cost-effectiveness of delivering universal and indicated school-based interventions to prevent the onset of major depression among youth in Australia. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26:545-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Stice E, Ragan J, Randall P. Prospective relations between social support and depression: differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Paukert AL, Phillips L, Cully JA, Loboprabhu SM, Lomax JW, Stanley MA. Integration of religion into cognitive-behavioral therapy for geriatric anxiety and depression. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15:103-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chandrashekar CR. Community interventions against depression. J Indian Med Assoc. 2007;105:638-639. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Glueckauf RL, Davis WS, Allen K, Chipi P, Schettini G, Tegen L, Jian X, Gustafson DJ, Maze J, Mosser B, Prescott S, Robinson F, Short C, Tickel S, VanMatre J, DiGeronimo T, Ramirez C. Integrative cognitive-behavioral and spiritual counseling for rural dementia caregivers with depression. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:449-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy and the new behavior therapies: Mindfulness, acceptance and relationship. In: Hayes SC, Follette VM, Linehan M, editors. Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive behavioral tradition. New York: Guilford Press, 2004: 1-29. |

| 24. | Kelly MA, Roberts JE, Bottonari KA. Non-treatment-related sudden gains in depression: the role of self-evaluation. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:737-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001 DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195118667.001.0001. |

| 26. | Hook JN, Worthington EL Jr, Davis DE, Jennings DJ 2nd, Gartner AL, Hook JP. Empirically supported religious and spiritual therapies. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:46-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mir G, Meer S, Cottrell D, McMillan D, House A, Kanter JW. Adapted behavioural activation for the treatment of depression in Muslims. J Affect Disord. 2015;180:190-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mir G, Ghani R, Meer S, Hussain G. Delivering a culturally adapted therapy for Muslim clients with depression. Cogn Behav Ther. 2019;1-14. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Martell CR, Addis ME, Jacobson NS. Depression in context: Strategies for guided action. New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 2001. |

| 30. | Lejuez CW, Hopko DR, Acierno R, Daughters SB, Pagoto SL. Ten year revision of the brief behavioral activation treatment for depression: revised treatment manual. Behav Modif. 2011;35:111-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ekers D, Webster L, Van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Richards D, Gilbody S. Behavioural activation for depression; an update of meta-analysis of effectiveness and sub group analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Moradveisi L, Huibers MJ, Renner F, Arasteh M, Arntz A. Behavioural activation v. antidepressant medication for treating depression in Iran: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:204-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kanter JW, Santiago-Rivera AL, Santos MM, Nagy G, López M, Hurtado GD, West P. A randomized hybrid efficacy and effectiveness trial of behavioral activation for Latinos with depression. Behav Ther. 2015;46:177-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kanter JW, Puspitasari AJ. Global dissemination and implementation of behavioural activation. Lancet. 2016;388:843-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21545] [Cited by in RCA: 28924] [Article Influence: 1205.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Rahman NK, Dawood S, Rehman N, Mansoor W, Ali S. Standardization of Symptom Checklist-R on psychiatric and non psychiatric sample of Lahore city. Pak J Clin Psychol. 2009;8:21-32. |

| 37. | Ekers D, Richards D, McMillan D, Bland JM, Gilbody S. Behavioural activation delivered by the non-specialist: phase II randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Pargament KI, Tarakeshwar N, Ellison CG, Wulff KM. Religious coping among the religious: The relationships between religious coping and well-being in a national sample of presbyterian clergy, elders, and members. J Sci Study Relig. 2001;40:497-513. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Beard C, Stein AT, Hearon BA, Lee J, Hsu KJ, Björgvinsson T. Predictors of Depression Treatment Response in an Intensive CBT Partial Hospital. J Clin Psychol. 2016;72:297-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Manos RC, Kanter JW, Luo W. The behavioral activation for depression scale-short form: development and validation. Behav Ther. 2011;42:726-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4140] [Cited by in RCA: 4474] [Article Influence: 165.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Rahman A, Hamdani SU, Awan NR, Bryant RA, Dawson KS, Khan MF, Azeemi MM, Akhtar P, Nazir H, Chiumento A, Sijbrandij M, Wang D, Farooq S, van Ommeren M. Effect of a Multicomponent Behavioral Intervention in Adults Impaired by Psychological Distress in a Conflict-Affected Area of Pakistan: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316:2609-2617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Egbewale BE, Lewis M, Sim J. Bias, precision and statistical power of analysis of covariance in the analysis of randomized trials with baseline imbalance: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Anik E. Feasibility Study for Assessment of Culturally Adapted Behavioural Activation for the Treatment of Depression. PhD, The University of Leeds. 2022. Available from: https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/32050/1/Anik_E_Medicine_PhD_2022.pdf. |

| 45. | Richards DA, Rhodes S, Ekers D, McMillan D, Taylor RS, Byford S, Barrett B, Finning K, Ganguli P, Warren F, Farrand P, Gilbody S, Kuyken W, O'Mahen H, Watkins E, Wright K, Reed N, Fletcher E, Hollon SD, Moore L, Backhouse A, Farrow C, Garry J, Kemp D, Plummer F, Warner F, Woodhouse R. Cost and Outcome of BehaviouRal Activation (COBRA): a randomised controlled trial of behavioural activation versus cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21:1-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Dimidjian S, Barrera M Jr, Martell C, Muñoz RF, Lewinsohn PM. The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:1-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Stoyanov D, Fulford B, Stanghellini G, Van Staden W, Wong, MT. International perspectives in values-based mental health practice: Case studies and commentaries. Switzerlan: Springer Nature, 2021. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 48. | Armento MEA, McNulty JK, Hopko DR. Behavioral activation of religious behaviors (BARB): Randomized trial with depressed college students. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2012;4:206-222. [DOI] [Full Text] |