Published online Nov 19, 2023. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v13.i11.862

Peer-review started: August 16, 2023

First decision: August 31, 2023

Revised: September 5, 2023

Accepted: October 25, 2023

Article in press: October 25, 202

Published online: November 19, 2023

Processing time: 93 Days and 0.3 Hours

There are many drawbacks to the traditional midwifery service management model, which can no longer meet the needs of the new era. The Internet + continuous midwifery service management model extends maternal management from prenatal to postpartum, in-hospital to out-of-hospital, and offline to online, thereby improving maternal and infant outcomes. Applying the Internet + continuous midwifery service management model to manage women with high-risk pregnancies (HRP) can improve their psycho-emotional opinion and, in turn, minimize the risk of adverse maternal and/or fetal outcomes.

To explore the effectiveness of a midwife-led Internet + continuous midwifery service model for women with HRP.

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of 439 women with HRP who underwent prenatal examination and delivered at Shanghai Sixth People's Hospital (affiliated to the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine) from April to December 2022. Among them, 239 pregnant women underwent routine obstetric management, and 200 pregnant women underwent Internet + contin

The data showed that in early pregnancy, the anxiety and depression levels of the two groups were similar; the levels gradually decreased as pregnancy progressed, and the decrease in the continuous group was more significant [31.00 (29.00, 34.00) vs 34.00 (32.00, 37.00), 8.00 (6.00, 9.00) vs 12.00 (10.00, 13.00), P < 0.05]. The maternal self-efficacy level and strategy for weight gain management were better in the continuous group than in the traditional group, and the effective rate of midwifery service intervention in the continuous group was significantly higher than in the control group [267.50 (242.25, 284.75) vs 256.00 (233.00, 278.00), 74.00 (69.00, 78.00) vs 71.00 (63.00, 78.00), P < 0.05]. The incidence of adverse delivery outcomes in pregnant women and newborns and fear of maternal childbirth were lower in the continuous group than in the traditional group, and nursing satisfaction was higher [10.50% vs 18.83%, 8.50% vs 15.90%, 24.00% vs 42.68%, 89.50% vs 76.15%, P < 0.05].

The Internet + continuous midwifery service model promotes innovation through integration and is of great significance for improving and promoting maternal and child health in HRP.

Core Tip: The Internet + continuous midwifery service model promotes innovation through integration, breaks the limitations of time and space in the traditional midwifery service supply mode, and enables pregnant women to enjoy high-quality nursing services at home. However, it is necessary to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of the midwife-led Internet + continuous midwifery service model, especially in women with high-risk pregnancies (HRP). By retrospectively analyzing the clinical data of 439 women with HRP, we clarified the positive effect of the midwife-led Internet + continuous midwifery service model on the psychological mood and pregnancy outcomes of women with HRP.

- Citation: Huang CJ, Han W, Huang CQ. Effect of Internet + continuous midwifery service model on psychological mood and pregnancy outcomes for women with high-risk pregnancies. World J Psychiatry 2023; 13(11): 862-871

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v13/i11/862.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v13.i11.862

High-risk pregnancies (HRP) are those with a high probability of dystocia, endangering the safety of the parturient and child. Data show that women with HRP in foreign countries account for 6% to 33% of all pregnant women[1], while the incidence of HRP in China is as high as 30%, which means that nearly one-third of pregnant women face adverse pregnancy outcomes such as dystocia, intrauterine death, postpartum hemorrhage, and puerperal infection. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines[2] indicate that effective communication, timely care, and treatment in early pregnancy, as well as professional care during and after delivery, can minimize the risk of adverse maternal and/or fetal outcomes.

In recent years, after a long period of practical exploration and theoretical research, domestic experts have achieved fruitful results in Internet + continuous midwifery service models. This service model overcomes the limitations of time and space of midwifery services, combines the advantages of the Internet, and gives full play to the subjective initiative of midwifery personnel. It can fully grasp the dynamic changes in parturients and newborns before, during, and after delivery and realize the long-term, continuous, and real-time management of pregnant and lying-in women by combining online and offline methods[3,4]. A systematic review pointed out that this nursing model enables pregnant women and midwives to establish partnerships during the prenatal, childbirth, and postpartum stages. Compared to other nursing models, it can reduce the necessity for maternal and infant treatment interventions[5]. Due to the gradual implementation of the Internet + continuous midwifery service model in maternal healthcare, a number of women with HRP were helped by the Internet + continuous midwifery service model between 2021 and 2022. However, it is necessary to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of the midwife-led Internet + continuous midwifery service model, especially the psychological emotions and pregnancy outcomes of women with HRP. This study retrospectively analyzed the role of the Internet + continuous midwifery service model for women with HRP.

First, this was a retrospective study. Clinical data of 439 women with HRP, who underwent prenatal examination and delivered at Shanghai Sixth People's Hospital affiliated to the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine from April 2022 to December 2022, were analyzed. According to the different midwifery service modes, participants were divided into a traditional group (TG, n = 239) and a continuous group (CG, n = 200). Inclusion criteria: (1) Age ≥ 18 years; (2) women with HRP with pregnancy risk assessment grade of “orange,” “red,” or “purple” in the “Maternal Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Management Standards” issued by the National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China; (3) women with HRP who can skillfully use an Internet smartphone; and (4) women with HRP who signed informed consent forms. Women with HRP with mental illness, who could not communicate, or lacked research data were excluded.

The TG adopted a routine obstetric management mode; that is, the prenatal and postpartum stages were mainly managed by doctors, and midwives participated in the entire process of maternal production. During the prenatal checkup phase, obstetricians perform routine examinations and provide health education to pregnant women. In the waiting room, midwives provide prenatal care to pregnant women experiencing pain. In the delivery room, midwives assist parturients with delivery, perform lateral incisions, correctly assess fetal conditions, and provide basic care. An obstetric nurse is responsible for nursing management in the postpartum stage, such as health education, diet guidance, and puerperal care. On the day of discharge, the obstetric nurse provides health education to the parturient and instructs her to attend the obstetric clinic for review and health guidance 42 d after delivery.

The CG implemented an Internet + continuous midwifery service model based on a traditional group, which was completed in three steps.

Step 1: Conduct expert meetings and establish a continuous midwifery service management team. Experts in related fields set up an expert group to put forward opinions and suggestions on the process and connotations of the Internet + continuous midwifery service mode. We have revised and improved these details. The continuous midwifery service management team comprised eight midwifery specialist nurses, three maternal and infant specialist nurses, and two neonatal specialist nurses. The head nurse of the department served as the group leader and was responsible for providing suggestions and opinions on the processes and connotations of continuous midwifery services. As the deputy leader, the head nurse was responsible for leading the team members to construct the initial implementation plan and organizing the members to carry out relevant training and assessment. In addition to participating in the above work, the remaining team members needed to implement Internet + continuous midwifery services for pregnant women.

Step 2: Establish an HRP Maternal Internet Communication Platform. During the recruitment of pregnant women participants, midwives invited them to join an Internet communication WeChat group and introduced WeChat group functions such as viewing popular science articles, downloading educational videos at different stages, and making group videos or voice calls. At the same time, team members were responsible for the implementation of WeChat group online interactions, irregularly and dynamically carrying out relevant health knowledge education for pregnant women and their families, and encouraging pregnant women to share their experiences and exchange experiences to indirectly alleviate maternal fear, anxiety, and other adverse psychological emotions. In addition, the midwives used videoconferencing software to regularly conduct pregnancy care courses and answer questions online. At the same time, the questionnaire star is used to collect relevant data.

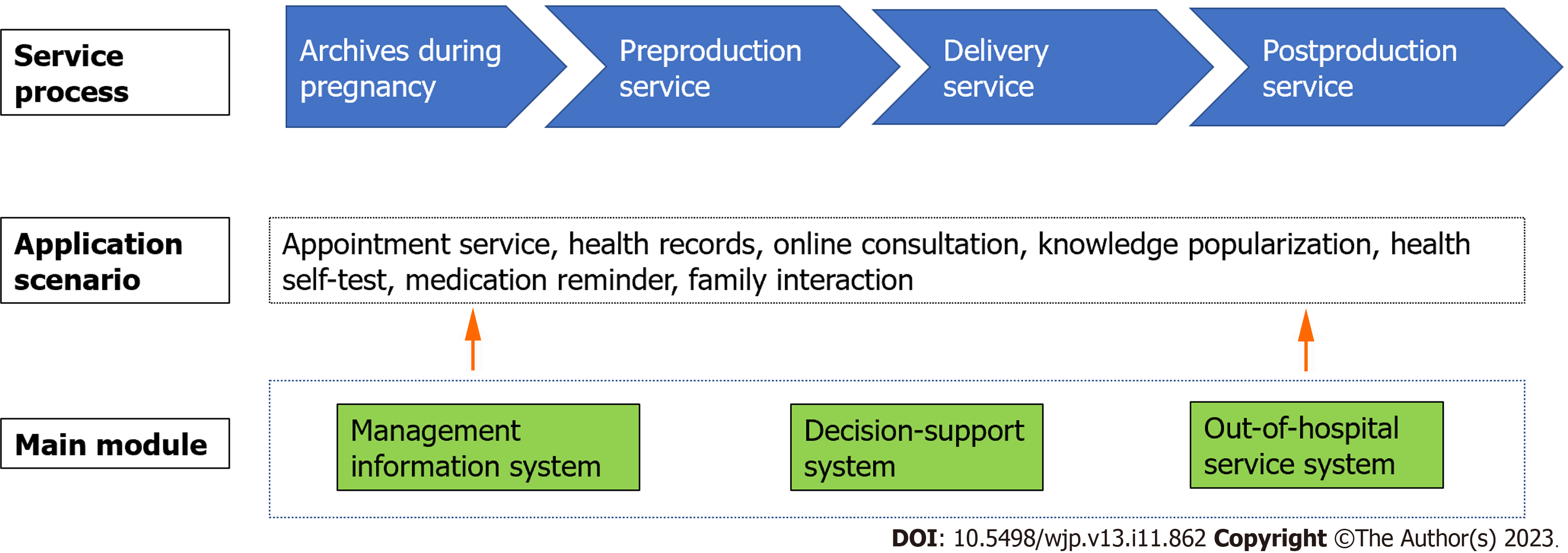

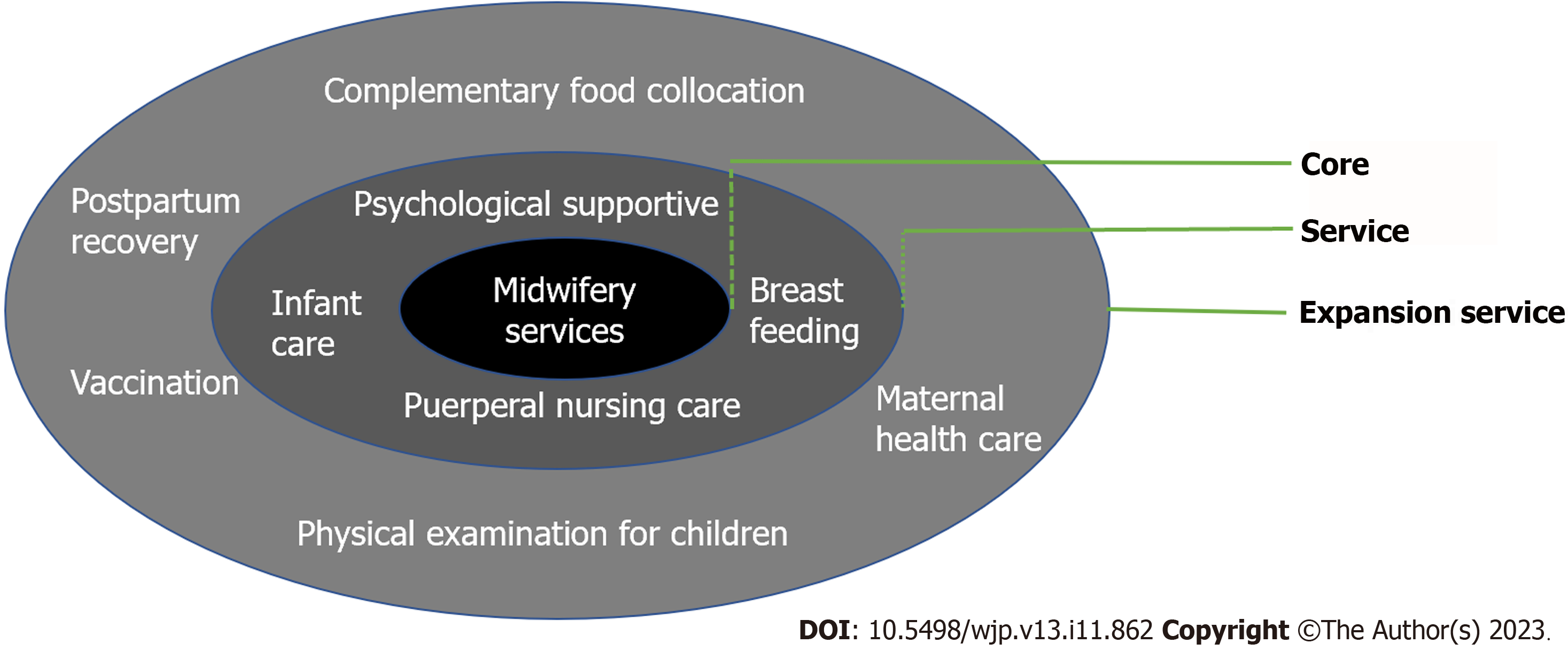

Step 3: Carrying out Internet and continuous midwifery services. The midwife-led Internet + continuous midwifery service is divided into three periods: Prenatal stage [(1) first trimester < 14 wk; (2) 14-28 wk in the second trimester; and (3) > 28 wk in the third trimester), delivery stage (labor to 2 h after delivery), postpartum stage (4-6 wk after delivery)]. The specific process is shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Prenatal stages: Midwives used pregnancy anxiety, fear of childbirth, delivery efficiency, and weight management scales to evaluate the relevant situations of pregnant women. Based on the results of the nutritional analysis and the situation of the pregnant women, a personalized pregnancy management plan was initially formulated. The WeChat group regularly introduced knowledge related to pregnancy care, childbirth, and child-rearing every week through video teaching, text, pictures, and small videos. At this stage, midwives regularly used online video conference calls to communicate with pregnant women one-on-one to understand their needs and conditions. In the third trimester of pregnancy, midwives provided maternal health education related to the delivery stage, including delivery methods, processes, and techniques, and played introductory online videos of maternity wards and delivery rooms to familiarize them with the environment and relieve anxiety.

Delivery stage: During the period from labor to two hours after delivery of the placenta, the team leader selected team members to be responsible for midwifery according to the individual situation of the parturient and provided corresponding nursing services. This included the assessment of maternal and infant conditions, regular monitoring of maternal and fetal conditions, all basic care during labor and delivery, preliminary examination of newborns after delivery, breastfeeding, treatment of the placenta, perineal incision or wound suture, and registration of neonatal birth.

Postpartum stage: Midwives provided postpartum health education for parturients and their families, including wound treatment, postpartum exercise nursing, neonatal feeding knowledge, and nursing. Midwives regularly communicated with parturients on WeChat every week to provide advice on puerperal care, breastfeeding, and maternal and child nutrition.

Main outcome measures: (1) Psychological Mood. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)[6] was used to evaluate anxiety. It included a total of 20 items, with a score of 1-4 and a total score of 20-80 points. The higher the score, the more serious the anxiety. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)[7,8] was used for the psychological assessment of depression, with a total of 10 items, a score of 0-3, and a total score of 0-30. Higher scores indicate more severe depression; and (2) Adverse delivery outcomes. The delivery outcomes of pregnant women and newborns were recorded, including postpartum hemorrhage, postpartum infection, premature rupture of membranes, neonatal asphyxia, fetal distress, fetal weight abnormalities, and premature delivery.

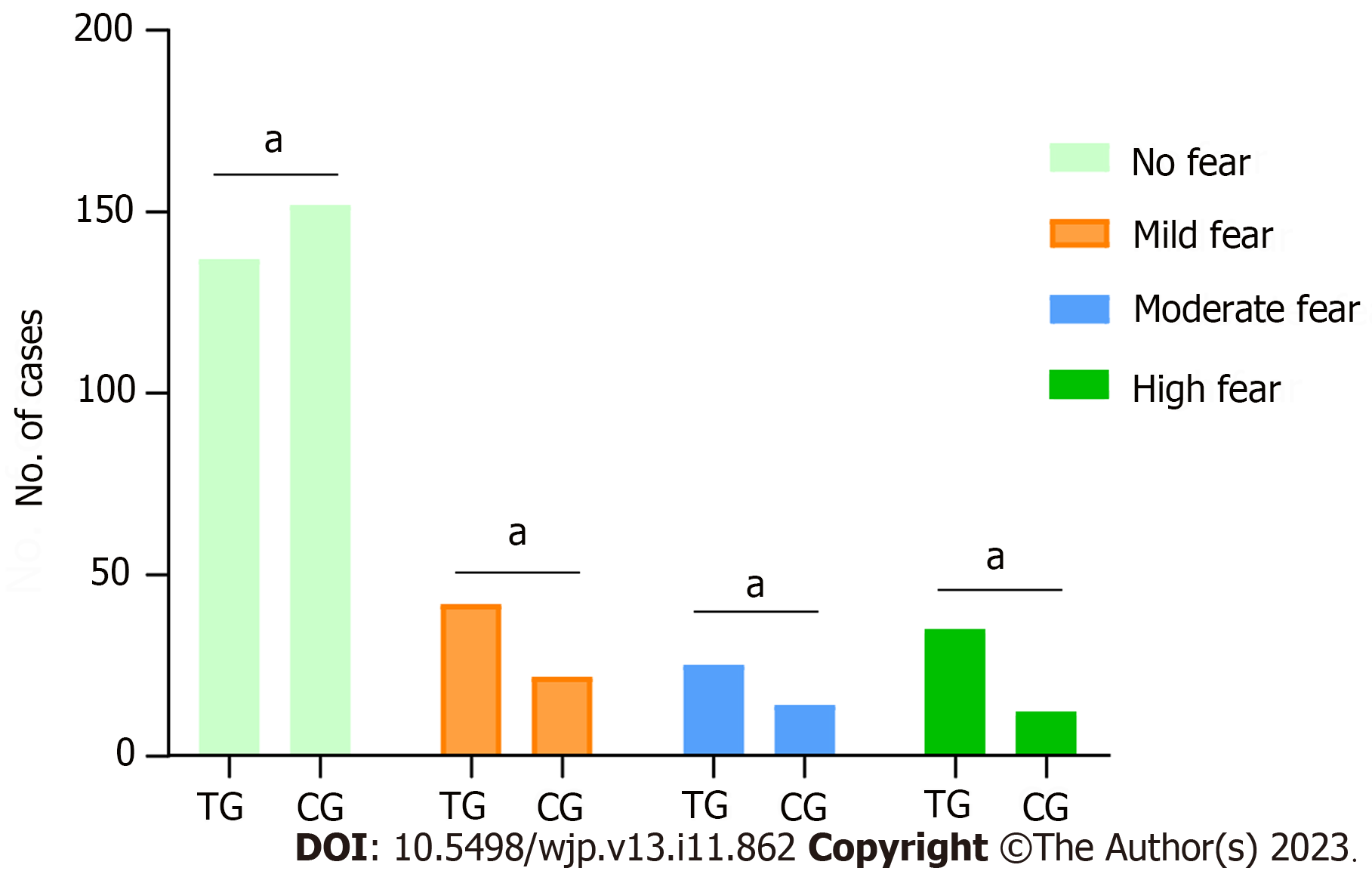

Secondary outcome: (1) Self-efficacy. A simplified Chinese version of the Childbirth Self-Efficacy Scale (CBSEI-C32)[9] was used for the measurements. The total score ranges from 32 to 320 points. Higher scores indicate higher delivery self-efficacy; (2) Childbirth Attitudes Questionnaire (CAQ)[10] was used to assess the fear of childbirth for women in late pregnancy. The total score was 16-64 points, with < 28 points indicating no fear of childbirth, 28-39 points indicating mild fear, 40-51 points indicating moderate fear, and 52-64 points indicating high fear; (3) Weight management. Pregnancy Weight Management Strategy Scale (PWMSS)[11] consists of 18 items, a 1-5 grade score, and a total score of 18-90 points. The higher the score, the more weight gain management strategies were used during pregnancy; and (4) Maternal nursing satisfaction was assessed using a self-administered nursing satisfaction questionnaire.

All data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0. Enumeration data were expressed as frequencies and constituent ratios, and measurement data with a non-normal distribution were expressed as interquartile ranges. Enumeration data were analyzed by χ2 test, and measurement data were analyzed by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to analyze the results of multiple measurements. The rank-sum test was used for the grade data. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

There was no statistical difference in the general clinical data between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Variables | TG (n = 239) | CG (n = 200) | χ2/Z value | P value |

| Age (yr), IQR | 29.00 (27.00, 32.00) | 30.00 (26.25, 33.00) | -1.591 | 0.112 |

| Types of pregnant women, n (%) | 2.196 | 0.138 | ||

| Primipara | 49 (20.50) | 53 (26.50) | ||

| Pluripara | 190 (79.50) | 147 (73.50) | ||

| Educational level, n (%) | 0.415 | 0.813 | ||

| Junior high school and below | 40 (16.70) | 37 (18.50) | ||

| High school or technical secondary school | 124 (51.80) | 98 (49.00) | ||

| Junior college and above | 75 (31.30) | 65 (32.50) | ||

| HRP factor, n (%) | ||||

| Pregnancy complication | 87 (36.40) | 68 (34.00) | 0.275 | 0.600 |

| Abnormal body mass index | 54 (22.50) | 33 (16.50) | 2.545 | 0.111 |

| Scarred uterus | 41 (17.10) | 37 (18.50) | 0.135 | 0.713 |

| Adverse pregnancy | 40 (16.70) | 31 (15.50) | 0.123 | 0.726 |

| Arrhythmia | 39 (16.30) | 25 (12.50) | 1.275 | 0.259 |

In the first trimester, the anxiety and depression levels of the two groups were similar and decreased gradually as pregnancy progressed; the CG decreased more significantly (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Groups | First trimester | Second trimester | Late pregnancy | Postpartum | F value | P value | |

| Anxiety | TG | 65.00 (60.00, 70.00) | 57.00 (53.00, 61.00) | 40.00 (37.00, 43.00) | 34.00 (32.00, 37.00) | 215.238 | < 0.05 |

| CG | 64.50 (59.00, 68.00) | 50.00 (46.00, 54.00) | 36.00 (31.25, 40.00) | 31.00 (29.00, 34.00) | |||

| Z value | -1.095 | -10.591 | -7.703 | -7.913 | |||

| P value | 0.274 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |||

| Depression | TG | 22.00 (20.00, 24.00) | 19.00 (17.00, 22.00) | 19.00 (16.00, 21.00) | 12.00 (10.00, 13.00) | 196.103 | < 0.05 |

| CG | 22.00 (19.00, 24.00) | 17.00 (14.25, 19.00) | 15.00 (13.00, 17.00) | 8.00 (6.00, 9.00) | |||

| Z value | -0.530 | -5.941 | -11.048 | -12.116 | |||

| P value | 0.596 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |||

There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the CBSEI-C32 scores in the first trimester (P > 0.05). The CBSEI-C32 scores increased as pregnancy progressed (P < 0.05), and the extent of the increase in the CG was greater than that in the TG (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Groups | First trimester | Second trimester | Late pregnancy | Postpartum | F value | P value |

| TG | 90.00 (83.00, 96.00) | 133.00 (123.00, 148.00) | 202.00 (187.00, 223.00) | 256.00 (233.00, 278.00) | 462.402 | < 0.05 |

| CG | 92.00 (82.00, 97.00) | 152.00 (139.00, 165.00) | 234.50 (214.25, 257.75) | 267.50 (242.25, 284.75) | ||

| Z value | -0.802 | -8.374 | -9.794 | -3.229 | ||

| P value | 0.423 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | 0.001 |

Overall, the effectiveness rate of midwifery interventions in the CG was significantly higher than that in the TG, and the degree of maternal fear of childbirth was lower; the difference was statistically significant (Z = -4.190, P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

In early pregnancy, there was no significant difference in PWMSS scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). The PWMSS score increased with an increase of pregnancy (P < 0.05). The PWMSS scores of the CG were better than those of the TG (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

| Groups | First trimester | Second trimester | Late pregnancy | Postpartum | F value | P value |

| TG | 33.00 (29.00, 38.00) | 42.00 (37.00, 47.00) | 68.00 (60.00, 73.00) | 71.00 (63.00, 78.00) | 30.284 | < 0.05 |

| CG | 33.00 (28.00, 36.00) | 45.00 (40.00, 50.00) | 68.00 (64.00, 73.00) | 74.00 (69.00, 78.00) | ||

| Z value | -0.743 | -3.992 | -2.004 | -3.059 | ||

| P value | 0.458 | < 0.05 | 0.045 | 0.002 |

In the TG, the incidence of adverse birth outcomes was 18.83% (45/239), and the incidence of adverse neonatal outcomes was 15.90% (38/239). In the CG, the incidence of adverse birth outcomes was 10.50% (21/200), and the incidence of adverse neonatal outcomes was 8.50% (17/200). The CG level was lower than the TG level (all P < 0.05) (Table 5).

| Groups | Parturients | χ2 value | P value | Child | χ2 value | P value | ||||||

| Postpartum hemorrhage | Postpartum infection | Premature rupture of membranes | Other | Neonatal asphyxia | Premature delivery | Abnormal fetal weight | Other | |||||

| TG | 15 (6.28) | 9 (3.77) | 8 (3.35) | 13 (5.44) | 5.912 | 0.015 | 8 (3.35) | 11 (4.60) | 7 (2.93) | 12 (5.02) | 5.44 | 0.02 |

| CG | 7 (3.50) | 4 (2.00) | 3 (1.50) | 7 (3.50) | 3 (1.50) | 5 (2.50) | 2 (1.00) | 7 (3.50) | ||||

The World Health Organization has reported that 50% of maternal deaths and more than 60% of neonatal deaths are caused by poor quality of care. Midwives who have received international standard education can provide women with planned pregnancy guidance and 87% of parturients and child basic care needs, while also avoiding more than 80% of maternal deaths, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths[12]. Among these, the quality of nursing before and after delivery and during puerperium is the focus of promoting maternal health. Prenatal monitoring and postpartum rehabilitation nursing are difficult to perform. It is difficult to fully understand the situation of parturients and newborns by simply relying on community home visits. To meet the nursing needs of women with HRP and compensate for the shortcomings of traditional maternal care services, the Internet + continuous midwifery service model, led by hospital midwives and combined with the advantages of the Internet, provides care to women with HRP and improves adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Regarding the prevalence of anxiety and depression in women with HRP, Dagklis et al[13,14] studied the incidence of depression in two HRP inpatient maternal samples (24.3% and 28%, respectively). Goetz et al[15] reported significant results. We found a similar trend in this study when compared to recently published inpatient samples. Women with HRP had significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression during early pregnancy. After the intervention of the Internet + continuous midwifery services, the levels of anxiety and depression gradually decreased as pregnancy progressed. As far as we know, the anxiety and depression of women with HRP are caused by many factors. On the one hand, the fear, worry, and pressure of coronavirus disease 2019 may endanger their own and fetal life and health; on the other hand, women with HRP are constrained by time and transportation problems and are unable to perform pregnancy tests on time, thus creating anxiety[16]. From the perspective of the space in which pregnant women receive midwifery services, traditional midwifery services are limited to the management process of pregnant women in hospital, unable to effectively supervise and guide pregnant women outside hospital and predict in advance the risk signals that may trigger HRP or produce adverse pregnancy outcomes. In the Internet + continuous midwifery service dominated by midwives, relying on the WeChat communication group, midwives can provide long-term, continuous, and real-time health counseling for pregnant women, management of normal pregnancy, delivery and puerperium, neonatal care, follow-up postpartum rehabilitation, women’s health care, children’s physical examinations, and vaccinations[17,18]. In long-term communication, midwives and pregnant women form a stable nurse-patient relationship, reduce the psychological burden on pregnant women, and alleviate anxiety and depression[19]. Self-efficacy refers to the belief that an individual can perform certain behavioral operations. It plays an important role in controlling or adjusting individual behavior and is related to psychological emotions[20]. Studies have found that the main cause of maternal anxiety is uncertainty in the delivery process and that good self-efficacy can reduce anxiety[21]. The above shows that Internet + continuous midwifery services can effectively improve the psychological mood of women with HRP and improve their self-efficacy.

The self-management ability of pregnant women plays an indispensable role in weight control during pregnancy, especially in compliance and daily life behaviors of pregnant women. Internet + continuous midwifery service completes the monitoring of health indicators independently by adopting online and offline methods, enhancing the sense of self-control of perinatal health care, promoting the formation of good self-management consciousness in pregnant women, and promoting the transformation of health behavior[22]. Ge et al[11] found that the self-efficacy of pregnant women can affect their weight management behaviors. Pregnant women can have a high degree of self-evaluation after realizing that they can manage their pregnancy weight well, which promotes weight management behaviors.

Due to the separate nature of previous midwifery services, contact between midwives and pregnant women was limited by time and space, resulting in problems such as a lack of knowledge and fear of childbirth. In CG, mobile Internet technology can effectively meet the diverse needs of pregnant women during pregnancy[23]. Midwives encouraged their families to participate in the learning of knowledge during pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum, and understand the psychological and physiological changes of pregnant women. They can provide pregnant women with more emotional support and positive encouragement during labor, which is conducive to reducing the fear of childbirth and achieving good pregnancy outcomes. This is consistent with the results of a previous study[5]. In addition, midwives work closely with the grassroots medical staff to cooperate and support each other in providing extended midwifery services. When necessary, midwives can use Internet technology to achieve information sharing and two-way referrals.

The combination of Internet- and midwife-led continuous midwifery services can effectively expand the use of high-quality nursing service resources, realize the integrated management of women with HRP before and after delivery, and support special groups of women with HRP. Midwives provide effective, economical, and convenient personalized nursing measures for pregnant women during pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium, which not only reduces the anxiety and depression of women with HRP, but also improves the quality of life of women with HRP and newborns.

There are many drawbacks to the traditional midwifery service management model that can no longer meet the needs of the new era. Dominated by midwives and combined with the advantages of the Internet, continuous midwifery services are provided to women with high-risk pregnancies (HRP) to alleviate adverse psychological emotions and improve pregnancy outcomes.

It is necessary to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of the midwife-led Internet + continuous midwifery service model, especially the psychological emotions and pregnancy outcomes of women with HRP.

To analyze the effect of a midwife-led Internet + continuous midwifery service model on the psychological mood and pregnancy outcomes of women with HRP.

The clinical data of 439 women with HRP were retrospectively analyzed. They were divided into different midwifery service modes (traditional and continuous groups). Psychological and emotional conditions, self-efficacy, incidence of adverse delivery outcomes, and nursing satisfaction were compared between the two groups.

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores of the two groups gradually decreased, with the continuous group decreasing faster than the traditional group. The incidence of adverse delivery and neonatal outcomes in the continuous group was 10.50% (21/200) and 8.50% (17/200), respectively, significantly lower than in the traditional group (18.83%, 45/239; 15.90%, 38/239, respectively).

The Internet + continuous midwifery service model gives full play to the subjective initiatives of pregnant women and midwives. It is of great significance to realize long-term, continuous, and real-time maternal management and ensure maternal and child safety through “prenatal-intrapartum-postpartum,” in-hospital and out-of-hospital, online, and offline care.

Midwives carry out corresponding Internet services according to different stages of pregnancy (early, middle, and late pregnancy), including the release of popular science articles on the public account, WeChat group communication, questionnaire star collection of relevant information, and network video conferences answering questions to guide women with HRP to carry out prenatal examinations and self-monitoring. Midwives can not only provide professional advice during pregnancy and childbirth but also provide extended quality nursing services to improve maternal satisfaction.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Alli SR, Canada; Hans H, Canada S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Holness N. High-Risk Pregnancy. Nurs Clin North Am. 2018;53:241-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2019 Feb- . [PubMed] |

| 3. | McCarthy R, Choucri L, Ormandy P, Brettle A. Midwifery continuity: The use of social media. Midwifery. 2017;52:34-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | McCarthy R, Byrne G, Brettle A, Choucri L, Ormandy P, Chatwin J. Midwife-moderated social media groups as a validated information source for women during pregnancy. Midwifery. 2020;88:102710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD004667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 505] [Article Influence: 56.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Han H, Wang L, Lu W, Dong J, Dong Y, Ying H. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Pregnant Women and Related Perinatal Outcomes. J Pers Med. 2022;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8260] [Cited by in RCA: 9475] [Article Influence: 249.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kozinszky Z, Dudas RB. Validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for the antenatal period. J Affect Disord. 2015;176:95-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zinsser LA, Schmidt G, Stoll K, Gross MM. Challenges in applying the short Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory (CBSEI-C32) in German. Eur J Midwifery. 2021;5:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhu X, Wang Y, Zhou H, Qiu L, Pang R. Adaptation of the Childbirth Experience Questionnaire (CEQ) in China: A multisite cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0215373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ge J, Zhao S, Peng X, Walker AN, Yang N, Zhou H, Wang L, Zhang C, Zhou M, You H. Analysis of the Weight Management Behavior of Chinese Pregnant Women: An Integration of the Protection Motivation Theory and the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model. Front Public Health. 2022;10:759946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Manu A, Arifeen S, Williams J, Mwasanya E, Zaka N, Plowman BA, Jackson D, Wobil P, Dickson K. Assessment of facility readiness for implementing the WHO/UNICEF standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities - experiences from UNICEF's implementation in three countries of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Dagklis T, Tsakiridis I, Chouliara F, Mamopoulos A, Rousso D, Athanasiadis A, Papazisis G. Antenatal depression among women hospitalized due to threatened preterm labor in a high-risk pregnancy unit in Greece. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:919-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dagklis T, Papazisis G, Tsakiridis I, Chouliara F, Mamopoulos A, Rousso D. Prevalence of antenatal depression and associated factors among pregnant women hospitalized in a high-risk pregnancy unit in Greece. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:1025-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Goetz M, Schiele C, Müller M, Matthies LM, Deutsch TM, Spano C, Graf J, Zipfel S, Bauer A, Brucker SY, Wallwiener M, Wallwiener S. Effects of a Brief Electronic Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Relieving Prenatal Depression and Anxiety in Hospitalized High-Risk Pregnant Women: Exploratory Pilot Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e17593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mirzakhani K, Shoorab NJ, Akbari A, Khadivzadeh T. High-risk pregnant women's experiences of the receiving prenatal care in COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Morse H, Brown A. UK midwives' perceptions and experiences of using Facebook to provide perinatal support: Results of an exploratory online survey. PLOS Digit Health. 2023;2:e0000043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Frøen JF, Myhre SL, Frost MJ, Chou D, Mehl G, Say L, Cheng S, Fjeldheim I, Friberg IK, French S, Jani JV, Kaye J, Lewis J, Lunde A, Mørkrid K, Nankabirwa V, Nyanchoka L, Stone H, Venkateswaran M, Wojcieszek AM, Temmerman M, Flenady VJ. eRegistries: Electronic registries for maternal and child health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Daly LM, Horey D, Middleton PF, Boyle FM, Flenady V. The Effect of Mobile App Interventions on Influencing Healthy Maternal Behavior and Improving Perinatal Health Outcomes: Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6:e10012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen J, Cai Y, Liu Y, Qian J, Ling Q, Zhang W, Luo J, Chen Y, Shi S. Factors Associated with Significant Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Pregnant Women with a History of Complications. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016;28:253-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Scabia A, Donati MA, Primi C, Lunardi C, Lino G, Dèttore D, Vannuccini S, Mecacci F. Depression, anxiety, self-efficacy and self-esteem in high risk pregnancy. Minerva Obstet Gynecol. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Halili L, Liu R, Hutchinson KA, Semeniuk K, Redman LM, Adamo KB. Development and pilot evaluation of a pregnancy-specific mobile health tool: a qualitative investigation of SmartMoms Canada. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018;18:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Amoakoh HB, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Amoakoh-Coleman M, Agyepong IA, Kayode GA, Sarpong C, Grobbee DE, Ansah EK. The effect of a clinical decision-making mHealth support system on maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity in Ghana: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18:157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |