Published online Oct 19, 2023. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v13.i10.763

Peer-review started: August 8, 2023

First decision: August 24, 2023

Revised: September 1, 2023

Accepted: September 20, 2023

Article in press: September 20, 2023

Published online: October 19, 2023

Processing time: 65 Days and 2.2 Hours

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-specific multi-system disease with multi-factor and multi-mechanism characteristics. The cure for preeclampsia is to terminate the pregnancy and deliver the placenta. However, it will reduce the perinatal survival rate, prolong the pregnancy cycle, and increase the incidence of maternal complications. With relaxation of the birth policy, the number of elderly pregnant women has increased significantly, and the prevalence rate of preeclampsia has increased. Inappropriate treatment can seriously affect the normal postpartum life of preg

To analyze the factors influencing preeclampsia in pregnant women complicated with postpartum anxiety, and to construct a personalized predictive model.

We retrospectively studied 528 pregnant women with preeclampsia who deli

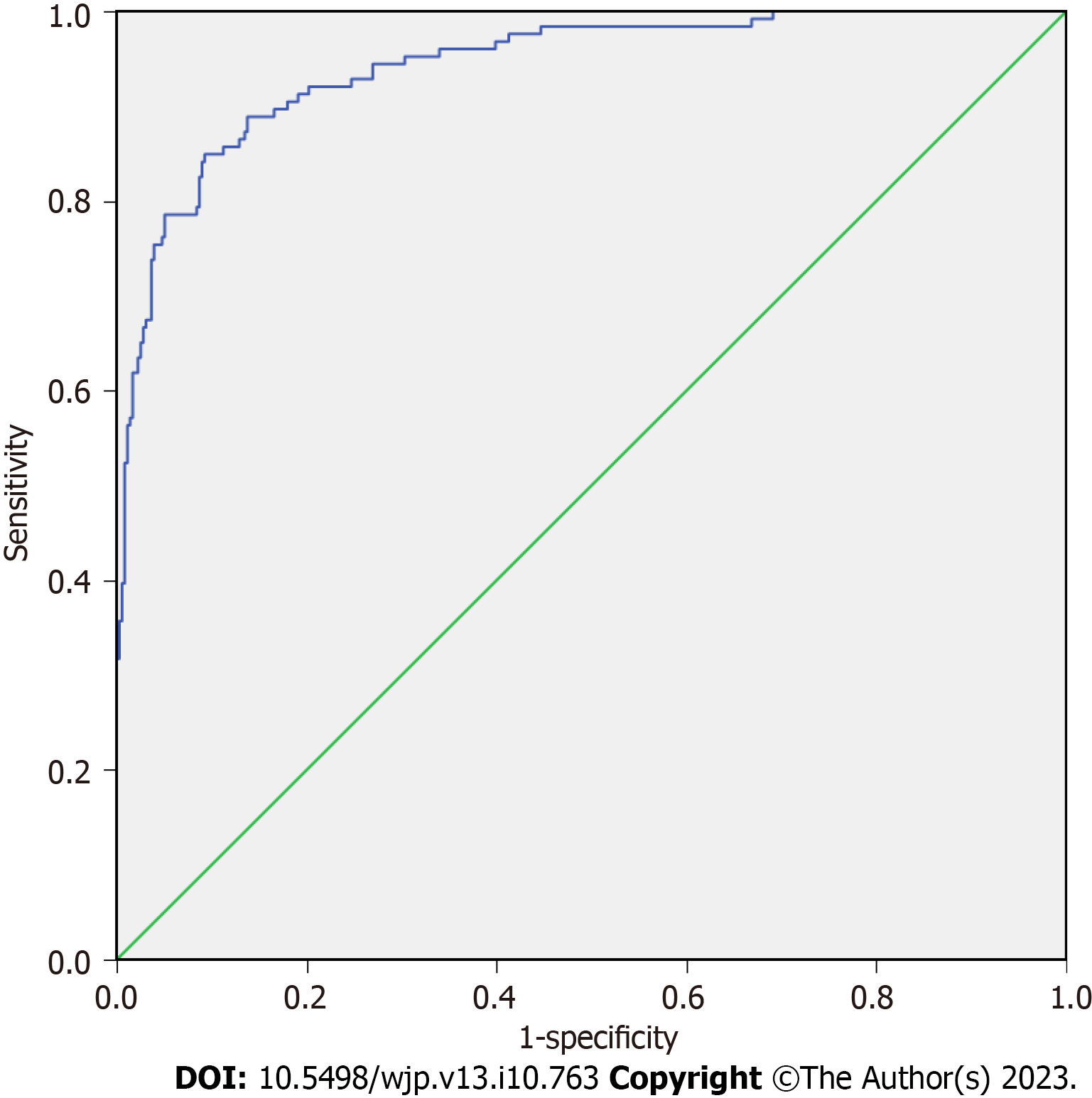

We excluded 46 of the 528 pregnant women with preeclampsia because of loss to follow-up and adverse outcomes. A total of 482 cases completed the assessment of postpartum anxiety 42 d after delivery, and 126 (26.14%) had postpartum anxiety. Bad marital relationship, gender discrimination in family members, hematocrit (Hct), estradiol (E2) hormone and interleukin (IL)-6 were independent risk factors for postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia (P < 0.05). Prediction model: Logit (P) = 0.880 × marital relationship + 0.870 × gender discrimination of family members + 0.130 × Hct - 0.044 × E2 + 0.286 × IL-6 - 21.420. The area under the ROC curve of the model was 0.943 (95% confidence interval: 0.919-0.966). The threshold of the model was -1.507 according to the maximum Youden index (0.757), the corresponding sensitivity was 84.90%, and the specificity was 90.70%. Hosmer-Leme

Poor marital relationship, family gender discrimination, Hct, IL-6 and E2 are the influencing factors of postpartum anxiety in preeclampsia women. The constructed prediction model has high sensitivity and specificity.

Core Tip: Preeclampsia is a progressive multisystem disease during pregnancy, characterized by new hypertension and proteinuria after 20 wk of pregnancy, and the condition develops continuously, which has a serious effect on the health of the mother and child. We analyzed the biochemical indicators of 528 pregnant women with preeclampsia and the inde

- Citation: Lin LJ, Zhou HX, Ye ZY, Zhang Q, Chen S. Construction and validation of a personalized prediction model for postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia. World J Psychiatry 2023; 13(10): 763-771

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v13/i10/763.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v13.i10.763

The incidence of preeclampsia can reach 8%[1], and studies have found that women with preeclampsia are more likely to suffer from postpartum anxiety[2-4], with an incidence of up to 20%[5]. Postpartum anxiety can aggravate maternal comorbidities, resulting in poor treatment compliance. Postpartum anxiety has short- or long-term adverse effects on maternal physical and mental health, as well as infant growth and development, and may lead to adverse events such as maternal drug abuse, suicide, and even infant injury[6,7]. Therefore, if we can predict the risk of postpartum anxiety in women with preeclampsia, targeted management and early intervention could avoid postpartum anxiety or improve postpartum psychological status. Current research focuses on the pregnancy outcome of women with preeclampsia, and few studies involve postpartum anxiety. In this study, we retrospectively studied 528 pregnant women with preeclampsia who delivered at our hospital between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2021. The risk factors for preeclampsia in preg

A total of 528 pregnant women with preeclampsia who delivered at Wenzhou Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Jianka between January 2018 and December 2021 were retrospectively selected. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Pre-eclampsia was diagnosed according to the relevant standards of obstetrics and gynecology[8]; (2) Con

The predictive model was clinically verified by retrospectively selecting 80 pregnant women with preeclampsia who met the above criteria in Wenzhou Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine between January and May 2022. Sample size calculation: (1) According to references, preeclampsia and the incidence of postpartum anxiety at about 20%, this study is expected to end in the multi-factor regression model analysis of 10 variables, according to the average number of events per predictor variable (EPV) sample size calculation, take EPV = 10, sample size = into variables × EPV/incidence rate = 10 × 10/20% = 500 cases, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and considering adverse outcomes, the sample size was 528; and (2) The sample size of the external validation was generally 1/4 to 1/2 of the modeling set, and the sample size = 1/4 of the modeling set, 120 cases (482/4) should be included. However, due to the influence of the external environment such as the epidemic situation and the actual situation of our hospital, 80 cases of preeclampsia pregnant women were finally included.

General information: Age, educational level and occupation of pregnant women; occupation and educational level of spouse; family economic status; emotional status of husband and wife (self-rated as good or bad); whether pregnancy was planned; whether there was experience of raising children; whether there was gender discrimination on the part of oneself or family members (expecting to have male or female baby); whether there was regular maternity examination; and history of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Laboratory indicators included: Routine blood tests [including hematocrit (Hct), hemoglobin, and platelet count]; estrogen [including estradiol (E2)]; liver function (including alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase); renal function (including creatinine and urea nitrogen); coagulation indicators (including fibrinogen and prothrombin time); and other biochemical indicators [including triglycerides and interleukin (IL)-6].

The self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) was used to determine whether the parturients who completed the study had post

The data obtained were processed by SPSS 27.0. Measurement data and numerical data were expressed as mean ± SD and percentage, respectively, using t and χ2 tests, respectively. The independent factors influencing postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia were analyzed using multifactor logistic regression and a predictive model was constructed. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were used to evaluate the calibration and discrimination of the predictive model. P < 0.05 indicated a significant difference.

We excluded 46 of 528 pregnant women with preeclampsia because of loss to follow-up and adverse outcomes, and 482 women completed the anxiety assessment 42 d after delivery. Among them, 126 women (26.14%) experienced postpartum anxiety. The analysis of baseline data of 482 pregnant women with preeclampsia showed that marital relationship, gender discrimination of family members, Hct, E2 and serum IL-6 levels were factors potentially influencing postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

| Variable | Postpartum anxiety (n = 126) | No postpartum anxiety (n = 356) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 31.80 ± 3.99 | 32.04 ± 4.09 | 0.491 | 0.624 |

| Degree of education | 1.853 | 0.396 | ||

| Junior high school and below | 31 (24.60) | 70 (19.66) | ||

| Senior high school (technical secondary school) | 61 (48.41) | 172 (48.31) | ||

| College (higher vocational) or above | 34 (26.98) | 114 (32.02) | ||

| Occupation | 5.433 | 0.143 | ||

| Unemployed | 25 (19.84) | 50 (14.04) | ||

| Workers and peasants | 43 (34.13) | 150 (42.13) | ||

| Public official | 19 (15.08) | 37 (10.39) | ||

| Other | 39 (30.95) | 119 (33.43) | ||

| Per capita monthly household income | 4.491 | 0.106 | ||

| < 2500 RMB yuan | 22 (17.46) | 68 (19.10) | ||

| 2500-5000 RMB yuan | 65 (51.59) | 146 (41.01) | ||

| > 5000 RMB yuan | 39 (30.95) | 142 (39.89) | ||

| Spousal occupation | 3.390 | 0.335 | ||

| Unemployed | 13 (10.32) | 20 (5.62) | ||

| Workers and peasants | 59 (46.83) | 181 (50.83) | ||

| Public official | 21 (16.67) | 57 (16.01) | ||

| Other | 33 (26.19) | 98 (27.53) | ||

| Education level of spouse | 3.994 | 0.136 | ||

| Junior high school and below | 19 (15.08) | 40 (11.24) | ||

| Senior high school (technical secondary school) | 58 (46.03) | 200 (56.18) | ||

| College (higher vocational) or above | 49 (38.89) | 116 (32.58) | ||

| Marital relationship | 37.665 | < 0.001 | ||

| Good | 39 (30.95) | 223 (62.64) | ||

| Bad | 87 (69.05) | 133 (37.36) | ||

| Whether it was a planned pregnancy | 1.338 | 0.247 | ||

| Yes | 80 (63.49) | 246 (69.10) | ||

| No | 46 (36.51) | 110 (30.90) | ||

| Have any experience raising children | 0.253 | 0.615 | ||

| Yes | 38 (30.16) | 99 (27.81) | ||

| No | 88 (69.84) | 257 (72.19) | ||

| Whether the pregnant woman herself has gender discrimination | 0.471 | 0.493 | ||

| Yes | 28 (22.22) | 90 (25.28) | ||

| No | 98 (77.78) | 266 (74.72) | ||

| Gender discrimination among family members | 24.318 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 86 (68.25) | 152 (42.70) | ||

| No | 40 (31.75) | 204 (57.30) | ||

| Whether regular birth inspection | 1.846 | 0.174 | ||

| Yes | 84 (66.67) | 260 (73.03) | ||

| No | 42 (33.33) | 96 (26.97) | ||

| History of adverse pregnancy outcomes | 0.256 | 0.613 | ||

| Yes | 30 (23.81) | 77 (21.63) | ||

| No | 96 (76.19) | 279 (78.37) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mean ± SD, mmHg) | 149.57 ± 7.3 | 149.50 ± 8.08 | -0.087 | 0.930 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mean ± SD, mmHg) | 100.37 ± 5.97 | 99.62 ± 6.70 | -1.113 | 0.266 |

| Hemoglobin (mean ± SD, g/L) | 108.47 ± 25.25 | 112.90 ± 30.02 | 1.700 | 0.090 |

| Hct (mean ± SD, %) | 63.16 ± 8.49 | 47.23 ± 6.18 | -22.421 | < 0.001 |

| Platelets (mean ± SD, × 109/L) | 137.72 ± 33.06 | 141.53 ± 32.63 | 1.121 | 0.263 |

| Fibrinogen (mean ± SD, g/L) | 4.38 ± 1.03 | 4.59 ± 1.11 | 1.749 | 0.081 |

| Prothrombin time (mean ± SD, s) | 10.96 ± 3.04 | 11.27 ± 3.01 | 0.991 | 0.322 |

| Creatinine (mean ± SD, mmol/L) | 60.64 ± 18.51 | 58.91 ± 16.86 | -0.963 | 0.336 |

| Urea nitrogen (mean ± SD, mmol/L) | 4.16 ± 1.09 | 3.99 ± 0.97 | -1.597 | 0.111 |

| Alanine transaminase (mean ± SD, U/L) | 27.21 ± 7.12 | 26.70 ± 7.23 | -0.685 | 0.494 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (mean ± SD, U/L) | 29.85 ± 9.05 | 28.82 ± 9.31 | -1.071 | 0.285 |

| Triglyceride (mean ± SD, mmol/L) | 4.67 ± 1.08 | 4.18 ± 1.09 | -1.657 | 0.098 |

| Estradiol (mean ± SD, pg/mL) | 50.23 ± 15.00 | 57.97 ± 11.95 | 5.845 | < 0.001 |

| Interleukin-6 (mean ± SD, pg/mL) | 56.39 ± 12.22 | 40.24 ± 10.12 | -14.554 | < 0.001 |

The significant factors above were used as covariates marital relationship (0 = good, 1 = bad), gender discrimination among family members (0 = none, 1 = yes). Concurrent postpartum anxiety was used as the dependent variable (0 = none, 1 = yes), and multifactor logistic regression analysis was performed. Bad marital relationship, gender discrimination among family members, Hct, E2 and IL-6 were independent risk factors for postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Factor | β | Wald χ2 | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| bad marital relationship | 0.880 | 4.594 | 0.032 | 2.412 (1.078-5.394) |

| Gender discrimination among family members | 0.871 | 4.339 | 0.037 | 2.390 (1.053-5.425) |

| Hematocrit | 0.130 | 35.391 | < 0.001 | 1.139 (1.091-1.189) |

| Eastradiol | -0.044 | 8.039 | 0.005 | 0.957 (0.928-0.986) |

| Interleukin-6 | 0.286 | 64.504 | < 0.001 | 1.331 (1.242-1.428) |

| Constant | -21.420 | 72.926 | < 0.001 |

According to the multivariate logistic regression model, a predictive model of postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia was constructed: Logit(P) = 0.880 × conjugal affection + 0.871 × gender discrimination in family members + 0.130 × Hct - 0.044 × E2 + 0.286 × IL-6 - 21.420. The ROC curve was drawn to evaluate the discrimination of the predictive model. The area under the ROC curve was 0.943 (95% confidence interval: 0.919-0.966). The threshold of the model was -1.507 according to the most approximate maximum Youden index (0.757), and the corresponding sensitivity and specificity were 0.849 and 0.907, respectively (Figure 1). The goodness-of-fit test was used to evaluate the calibration of the predictive model, which showed Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 = 5.900, and P = 0.658 (Figure 2).

We retrospectively selected 80 pregnant women with preeclampsia in our hospital between January and May 2022 to clinically verify the predictive model. The sensitivity was 81.82%, specificity 84.48%, and accuracy 83.75% (Table 3).

| Postpartum anxiety | Models predict postpartum anxiety | Total | |

| Yes | No | ||

| Yes | 18 | 4 | 22 |

| No | 9 | 49 | 58 |

| Total | 27 | 53 | 80 |

The results of this study showed that serum transaminase levels, blood pressure, platelet levels, and coagulation indi

There is a biological basis for postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia. Postpartum estrogen deficiency is an important reason for the significantly increased incidence of mental illness at 30 d postpartum[12], and E2 level is negatively correlated with the severity of female anxiety[13], which is similar to our study. The possible causes are that E2 can play an antianxiety role by improving the binding rate of serotonin reuptake transporter and the reuptake capacity of cells for serotonin. However, postpartum estrogen secretion from the uterus is stopped, the recovery of ovarian estrogen secretion function is slow, and the level of E2 is low, thus the antianxiety effect is weakened. If the level of E2 is low in pregnant women with preeclampsia, it may further decrease the level of postpartum estrogen, so anxiety is more likely to occur[14,15]. Ramiro-Cortijo et al[16] confirmed that the Hct in patients with preeclampsia was significantly higher than that of healthy people, and increased with aggravation of preeclampsia. Noori et al[17] showed that the pre

In this study, a risk predictive model for pregnant women with preeclampsia complicated with postpartum anxiety was constructed based on the above independent influencing factors (bad marital relationship, gender discrimination of family members, Hct, IL-6 and E2). The ROC curve analysis results showed that the predictive model had good discrimination, and the goodness-of-fit test showed that the model had good calibration. The prospective clinical validation showed that the model had high sensitivity (81.82%), specificity (84.48%) and accuracy (83.75%), indicating that the predictive model had clinical practicability. The model was simple to use and had high accuracy. However, the number of cases in the time period selected for clinical verification is small, and the results may have certain errors. In the future will be incorporated into various validation.

Bad marital relationship, gender discrimination of family members, Hct, IL-6 and E2 are independent factors influencing postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia. The predictive model established based on these factors has high sensitivity, specificity and accuracy, strong operability, and high clinical value. However, this study was a single-center study, the clinical validation of the model was only conducted in our hospital, and the sample size was insufficient, so the results were inevitably biased. In the future, multi-center research and multi-center clinical verification will be carried out, and multi-factor, multi-sample and multi-time span will be adopted to explore, so as to enhance the reliability of the research results.

Relaxation of the maternity policy has resulted in an increase in the number of elderly pregnant and lying-in women, and the prevalence of preeclampsia. Preeclampsia can lead to organ damage and system dysfunction.

To explore the factors influencing postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia and construct a predictive model, to provide an effective and practical risk assessment tool for clinical practice.

The object of this study is to explore the factors influencing postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia and construct a personalized model for predicting postpartum anxiety, to provide a reference for clinical trials.

We retrospectively analyzed 528 pregnant women with preeclampsia who delivered in our hospital between 2018 and 2021. Various physiological and biochemical indicators were obtained through laboratory tests. Multivariate logistic regression, receiver operating characteristic curve, Hosmer-Lemeshow and other methods were used to analyze the factors influencing postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia and to construct a predictive model.

A total of 126 pregnant women with preeclampsia experienced postpartum anxiety. Bad marital relationship, gender discrimination among family members, hematocrit, estradiol hormone and interleukin-6 were independent risk factors for postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia, and the predictive model constructed based on these factors had high accuracy.

We analyzed the factors influencing postpartum anxiety in pregnant women with preeclampsia and constructed a predictive model with high sensitivity and accuracy, which provided a reference value for clinical practice.

Firstly, multi-sample, multi-factor, multi-center and multi-time span clinical studies will be carried out in the future to enhance the reliability of the research results. In addition, different models were constructed for clinical application in pregnant women with preeclampsia and postpartum anxiety.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kolla NJ, Canada; Leenen FH, Canada S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 88.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Postma IR, Bouma A, Ankersmit IF, Zeeman GG. Neurocognitive functioning following preeclampsia and eclampsia: a long-term follow-up study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:37.e1-37.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Roberts L, Davis GK, Homer CSE. Depression, Anxiety, and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Following a Hypertensive Disorder of Pregnancy: A Narrative Literature Review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abedian Z, Soltani N, Mokhber N, Esmaily H. Depression and anxiety in pregnancy and postpartum in women with mild and severe preeclampsia. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2015;20:454-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nakić Radoš S, Tadinac M, Herman R. Anxiety During Pregnancy and Postpartum: Course, Predictors and Comorbidity with Postpartum Depression. Acta Clin Croat. 2018;57:39-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kendig S, Keats JP, Hoffman MC, Kay LB, Miller ES, Moore Simas TA, Frieder A, Hackley B, Indman P, Raines C, Semenuk K, Wisner KL, Lemieux LA. Consensus Bundle on Maternal Mental Health: Perinatal Depression and Anxiety. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:422-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jordan V, Minikel M. Postpartum anxiety: More common than you think. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:165;168;170;174. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Tanaka ME, Keefe N, Caridi T, Kohi M, Salazar G. Interventional Radiology in Obstetrics and Gynecology: Updates in Women's Health. Radiographics. 2023;43:e220039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pawluski JL, Lonstein JS, Fleming AS. The Neurobiology of Postpartum Anxiety and Depression. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:106-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jack SM, Boyle M, McKee C, Ford-Gilboe M, Wathen CN, Scribano P, Davidov D, McNaughton D, O'Brien R, Johnston C, Gasbarro M, Tanaka M, Kimber M, Coben J, Olds DL, MacMillan HL. Effect of Addition of an Intimate Partner Violence Intervention to a Nurse Home Visitation Program on Maternal Quality of Life: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321:1576-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Huang C, Fan Y, Hu S. The Prevalence and Influencing Factors of Postpartum Depression Between Primiparous and Secundiparous. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2023;211:190-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fan F, Zou Y, Tian H, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Ma X, Meng Y, Yue Y, Liu K, Dart AM. Effects of maternal anxiety and depression during pregnancy in Chinese women on children's heart rate and blood pressure response to stress. J Hum Hypertens. 2016;30:171-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhu W, Chen Z, Shen Y, Wang H, Cai X, Zhu J, Tang Y, Wang X, Li S. Relationship between serum gonadal hormone levels and synkinesis in postmenopausal women and man with idiopathic facial paralysis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2022;49:782-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bhatia NY, Ved HS, Kale PP, Doshi GM. Importance of Exploring N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) as a Future Perspective Target in Depression. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2022;21:1004-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Edinoff AN, Odisho AS, Lewis K, Kaskas A, Hunt G, Cornett EM, Kaye AD, Kaye A, Morgan J, Barrilleaux PS, Lewis D, Viswanath O, Urits I. Brexanolone, a GABA(A) Modulator, in the Treatment of Postpartum Depression in Adults: A Comprehensive Review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:699740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ramiro-Cortijo D, de la Calle M, Rodriguez-Rodriguez P, Phuthong S, López de Pablo ÁL, Martín-Cabrejas MA, Arribas SM. First trimester elevations of hematocrit, lipid peroxidation and nitrates in women with twin pregnancies who develop preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2020;22:132-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Noori M, Donald AE, Angelakopoulou A, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Prospective study of placental angiogenic factors and maternal vascular function before and after preeclampsia and gestational hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:478-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Demirer S, Hocaoglu M, Turgut A, Karateke A, Komurcu-Bayrak E. Expression profiles of candidate microRNAs in the peripheral blood leukocytes of patients with early- and late-onset preeclampsia versus normal pregnancies. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2020;19:239-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maes M, Berk M, Goehler L, Song C, Anderson G, Gałecki P, Leonard B. Depression and sickness behavior are Janus-faced responses to shared inflammatory pathways. BMC Med. 2012;10:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jia Y, Liu L, Sheng C, Cheng Z, Cui L, Li M, Zhao Y, Shi T, Yau TO, Li F, Chen L. Increased Serum Levels of Cortisol and Inflammatory Cytokines in People With Depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2019;207:271-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |