Published online Sep 19, 2022. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i9.1233

Peer-review started: March 21, 2022

First decision: May 30, 2022

Revised: June 16, 2022

Accepted: August 5, 2022

Article in press: August 5, 2022

Published online: September 19, 2022

Processing time: 182 Days and 16.4 Hours

Preterm birth (PTB) is one of the main causes of neonatal deaths globally, with approximately 15 million infants are born preterm. Women from the Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) populations maybe at higher risk of PTB, therefore, the mental health impact on mothers experiencing a PTB is particularly important, within the BAME populations.

To determine the prevalence of mental health conditions among BAME women with PTB as well as the methods of mental health assessments used to characterise the mental health outcomes.

A systematic methodology was developed and published as a protocol in PROSPERO (CRD420

Thirty-nine studies met the eligibility criteria from a possible 3526. The prevalence rates of depression among PTB-BAME mothers were significantly higher than full-term mothers with a standardized mean difference of 1.5 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) 29%-74%. The subgroup analysis indicated depressive symptoms to be time sensitive. Women within the very PTB category demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of depression than those categorised as non-very PTB. The prevalence rates of anxiety and stress among PTB-BAME mothers were significantly higher than in full-term mothers (odds ratio of 88% and 60% with a CI of 42%-149% and 24%-106%, respectively).

BAME women with PTB suffer with mental health conditions. Many studies did not report on specific mental health outcomes for BAME populations. Therefore, the impact of PTB is not accurately represented in this population, and thus could negatively influence the quality of maternity services they receive.

Core Tip: Preterm birth is a multi-etiological condition and a leading cause of perinatal mortality and morbidity. This study demonstrates the mental health impact due to preterm birth among the Black, Asian and Ethnic minority women. There is minimal research available at present around this subject matter, and this important disease sequelae.

- Citation: Delanerolle G, Zeng YT, Phiri P, Phan T, Tempest N, Busuulwa P, Shetty A, Raymont V, Rathod S, Shi JQ, Hapangama DK. Mental health impact on Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic populations with preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry 2022; 12(9): 1233-1254

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v12/i9/1233.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i9.1233

Preterm birth (PTB) is a multi-etiological condition and a leading cause of perinatal mortality and morbidity[1]. PTB can be categorized as per the World Health Organization classification methods as extreme preterm (gestational age < 28 wk), very preterm (gestational age of 28-32 wk) and moderately preterm (32-37 wk). Most preterm infants are at risk of developing respiratory and gastrointestinal complications[2]. The PTB rates are higher in most developed regions of the world, despite advances in medicine. PTB are at the highest level in the US for between 12%-15% and 5%-9% in Europe. In comparison, PTB rates in China range between 4.7%-18.9% (1987-2006) and Taiwan 8.2%-9.1%[3]. The prevalence of PTB increased from 9.8% in 2000 to 10.6% by 2014 and has become a global public health issue[1]. However, the mental health impact associated with PTB is not extensively examined, despite it potentially may exacerbate the patient’s experience of a distressing birth. Furthermore, clearly pronounced risk of PTB among Black women have been reported in studies from United States or United Kingdom[4,5], with limited data on the risk among other ethnic groups. While health disparities, social deprivation are recognised risk factors for PTB that are also frequently associated with Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) populations, the available data on ethnic disparities associated with PTB remains limited.

In the United Kingdom, health disparities within Caribbean and West African populations demonstrate a significant risk of very PTB in comparison to Caucasians. Similar risks within the South Asian community appear to be less consistent in comparison to Caucasian PTB women[11]. In the United Kingdom, National Health Service (NHS) England reports improvements to maternity services are a priority as part of the NHS 10-year plan[12]. As per the 2018 Public Health England report on maternity services, 1 in 4 of all births within Wales and England were to mothers born outside the United Kingdom[12]. Additionally, 13% of all infants born between 2013-2017 are from the BAME population[12]. Importantly, Black women were 5 times more at risk of death during parturition and Asian babies are 73% more likely to result in neonatal death compared to Caucasian women[12], therefore, the mental health impact experienced by PTB mothers is vital to evaluate particularly in the BAME population. A number of socio-economic, genetic and obstetric causes have been proposed to explain mental health disorders among PTB women, but these theories do not fully explain the aetiology. Furthermore, they also exclude the bidirectional relationship between PTB, and mental health conditions demonstrated by some studies[13,18,19].

This available evidence demonstrates a need to explore the mental health impact on BAME women with PTB. We believe that gathering this evidence would inform the forthcoming evidence-based women’s health strategy in the United Kingdom to explore both the physical and mental health components, and to be inclusive using cultural adaptations where appropriate.

An evidence synthesis methodology was developed using a systematic protocol that was developed and published on PROSPERO (CRD42020210863). The aims of the study were to determine the prevalence of mental health conditions among BAME women with PTB as well as the mental health assessments used to characterise the mental health outcomes.

Multiple databases were used, including PubMed, EMBASE, Science direct, and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials for the data extraction process. Searches were carried out using multiple keywords and MeSH terms such as “Depression”, “Anxiety”, “Mood disorders”, “PTSD”, “Psychological distress”, “Psychological stress”, “Psychosis”, “Bipolar”, “Mental Health”, “Unipolar”, “self-harm”, “BAME”, “Preterm birth”, “Maternal wellbeing” and “Psychiatry disorders”. These terms were then expanded using the ‘snow-ball’ method and the fully developed methods are in the supplementary section (Supplementary material).

All eligible randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs published in English were included. The final dataset was reviewed independently. Multiple mental health variables were used alongside of the 2 primary variables of PTB and BAME.

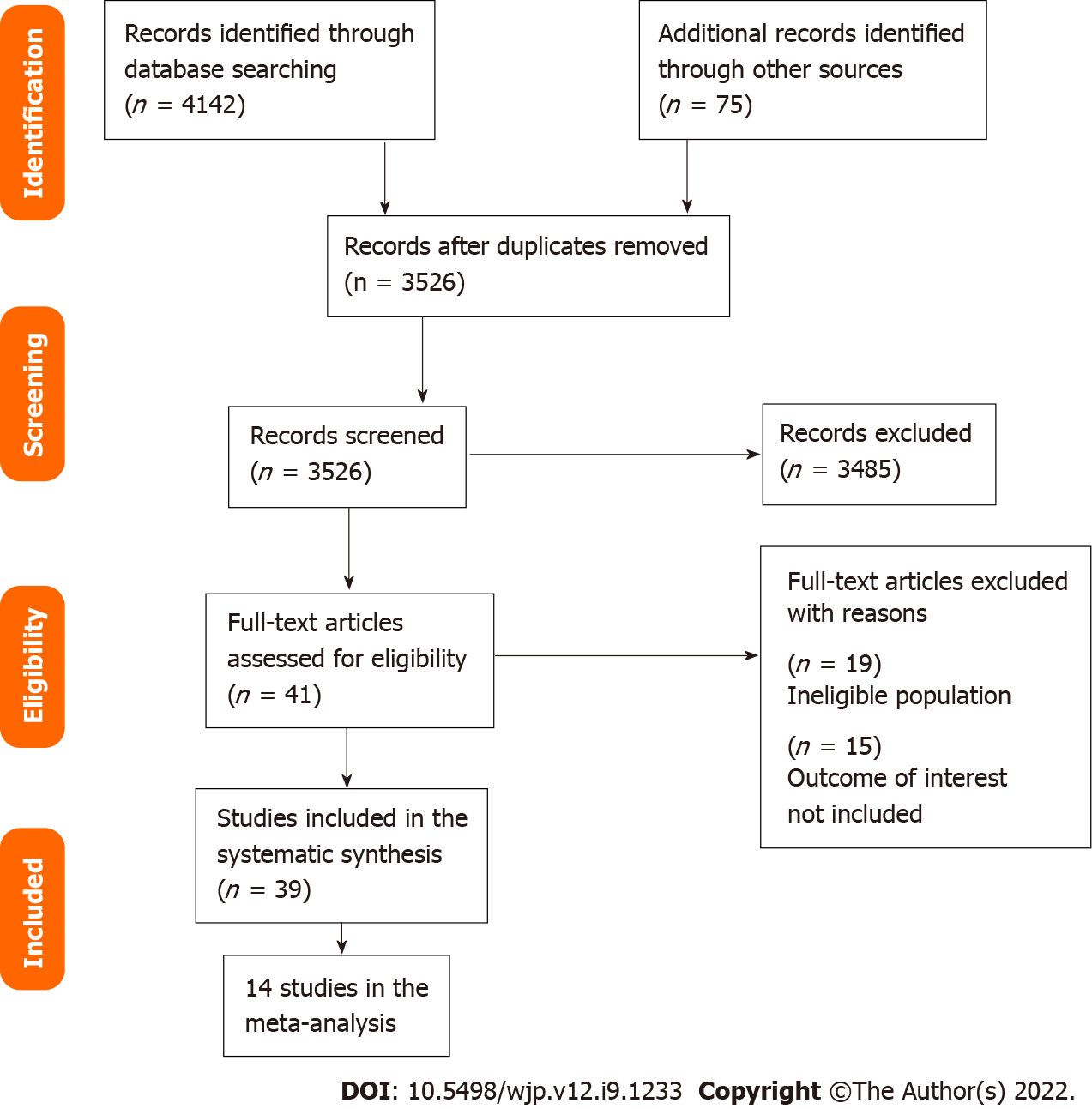

The extraction and eligibility has been demonstrated using a PRISMA diagram. The data was collected using Endnote and Microsoft excel. Stata 16.1 was used as a way to complete the final statistical analysis. Standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were extracted for analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed by way of funnel plots, χ2-test (P value) and I2. A sub-group analysis was conducted to determine the mental health symptomatologies identified and the geographical location.

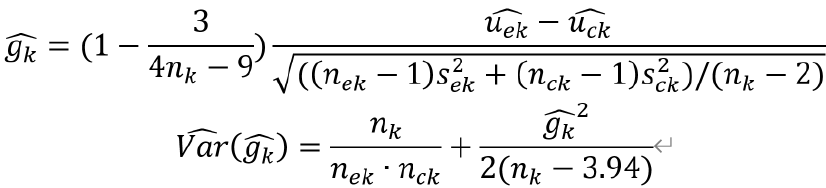

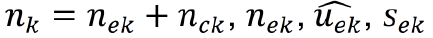

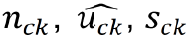

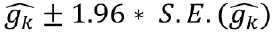

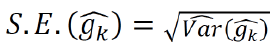

Due to the unified use of mental health assessments, in order to standardize the mean differences reported within each study, the following mathematical method was used[25-27]:

are the number, mean and standard variation of exposed group and

are the number, mean and standard variation of exposed group and  are the number, mean and standard variation of control group. Then we can obtain the 95% confidence interval by

are the number, mean and standard variation of control group. Then we can obtain the 95% confidence interval by  where

where  .

.

To eliminate heterogeneity, a meta-regression and sub-group analyses were conducted by mental health assessment timepoints and country.

To further analyse the heterogeneity of studies reporting depression and anxiety, a sensitivity analysis was conducted.

Studies included within this study were critically appraised individually using mental health variables. All studies appraised for methodological quality and risk of bias based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which is commonly used for cross-sectional and/or cohort studies as demonstrated by Wells et al[73]. These could be further modified using the adapted NOS version as reported by Modesti et al[74]. The NOS scale includes 8 items within 3 specific quality parameters of selection, outcome and comparability. The quality of these studies was reported as good, fair or poor based on the details below: Good quality score of 3 or 4 stars were awarded in selection, 1 or 2 in comparability and 2 or 3 stars in outcomes; Fair quality score of 2 stars were awarded in selection, 1 or 2 stars in comparability and 2 or 3 stars in outcomes; Poor quality score was allocated 0 or 1 star in selection, 0 stars in comparability and 0 or 1 star in outcomes.

The following outcomes were included within the meta-analysis: Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms, and parenting stress; Clinical significance of the data identified; Critical interpretive synthesis of common mental health reported outcomes.

Outcomes such as post-partum depression could not be synthesised for the meta-analysis. Therefore, these aspects have been included in the narrative analysis only.

Publication bias is a concern to the validity of conclusion of a meta-analysis. As a result, several methods could be used to assess this aspect. An egger’s test was used to report on publication bias. Additionally, a trim and fill (TAF) method was used to analyze the influence of publication bias. TAF estimates any missing studies due to publication bias within the funnel plot to adjust the overall effect estimate.

A representative from a patient-public focus group associated with a multi-morbid project investigating women’s physical and mental health sequelae was invited to review the protocol and the resulting paper. This is a vital facet of developing and delivering an authentic evidence synthesis to reduce the gap between evidence production, development of solutions to address the identified gaps and the implementation of the solutions into practice as well as their acceptability by patients.

Of the 3526 studies, 39 met the eligibility criteria. All 39 studies reported the mental health status of BAME women with PTB although it remained unclear if they reported mental health symptoms or clinical diagnoses. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA diagram. The mental health assessments and frequency of the data gathering varied across studies. The 39 studies primarily reported stress, anxiety and depression as indicated in Table 1 along with other characteristics. The quality assessment using the Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS) and Risk of Bias identified within the pooled studies are shown in Tables 2 and 3 and Supplementary Table 1. Brief description of various scales used to assess depression, anxiety, and stress across studies is presented in the supplementary file on Mental Health Questionnaires.

| ID | Ref. | Study type | Country | Symptoms | Outcome assessment1 | ||

| 1 | Ballantyne et al[37] | Cross-sectional study | Canada | Depression | Stress | (1) CES-D; and (2) PSS: NICU | |

| 2 | Baptista et al[48] | Cross-sectional study | Portugal | Psychological problem | Stress | (1) BSI; and (2) Daily hassles questionnaire | |

| 3 | Barroso et al[38] | Cross sectional study | United States | Depression | EPD-S | ||

| 4 | Bener[60] | Hospital-based study (cross sectional study) | Qatar | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | (1) DASS-21; (2) DASS-21; and (3) DASS-21 |

| 5 | Bouras et al[34] | Cross-sectional study | Greece | Depression | Anxiety | (1) BDI; and (2) STAI | |

| 6 | Brandon et al[39] | Descriptive study | United States | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | (1) EPDS; (2) STAI-S; (3) PPQ; and (4) CHWS |

| 7 | Carson et al[49] | Cohort study | United Kingdom | Psychological problem | Modified RMI | ||

| 8 | Cheng et al[13] | Cohort study | United States | Depression | CES-D | ||

| 9 | Davis et al[57] | Cross-sectional study | Australia | Depression | Stress | (1) EPDS; and (2) DASS | |

| 10 | Drewett et al[50] | Cross-sectional study | United Kingdom | Depression | EPDS | ||

| 11 | Edwards et al[58] | Cohort study | Australia | Depression | Parenting stress | (1) EPDS; and (2) PSI | |

| 12 | Fabiyi et al[40] | Cross-sectional study | United States | (1) State anxiety; and (2) Trait anxiety | STAI | ||

| 13 | Gambina et al[33] | Case-control study | Italy | Depression | (1) State anxiety; and (2) Trait anxiety | Stress | (1) EPDS; (2) STAI-State and STAI-Trait; and (3) PSM |

| 14 | Gueron-Sela et al[30] | Cross-sectional study | Israel | Depression | Stress | (1) CES-D; and (2) PSS: NICU | |

| 15 | Gulamani et al[24] | Cohort study | Pakistan | Depression | EPDS | ||

| 16 | Gungor et al[35] | Case-control study | Turkey | Depression | (1) State anxiety; (2) Trait anxiety | (1) BDI; and (2) STAI | |

| 17 | Hagan et al[59] | Prospective, randomised, controlled study | Australia | Depression | Anxiety | (1) EPDS; and (2) BDI | |

| 18 | Henderson et al[51] | Cross-sectional study | United Kingdom | Depression | EPDS | ||

| 19 | Holditch-Davis et al[44] | Cross-sectional study | United States | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | (1) CES-D; (2) STAI; and (3) PSS: NICU |

| 20 | Ionio et al[52] | Longitudinal study | Italy | Depression | Profile of mood states | ||

| 21 | Logsdon et al[41] | Descriptive study | United States | Depression | CES-D | ||

| 22 | Misund et al[53] | Longitudinal study | Norway | Psychological distress | Anxiety | Trauma-related stress | (1) GHQ likert sum and case sum; (2) STAI-X1; and (3) Impact of event scale (IES) |

| 23 | Misund et al[53] | Cohort study | Norway | Psychological distress | Anxiety | Trauma-related stress | (1) GHQ likert sum and case sum; (2) STAI-X1; and (3) IES |

| 24 | Pace et al[32] | Longitudinal, prospective, follow-up cohort study | Australia | Depression | Anxiety | (1) CES-D; and (2) Hospital anxiety and depression scale | |

| 25 | Rogers et al[42] | Cohort study | United States | Depression | Anxiety | (1) EPDS; and (2) STAI | |

| 26 | Sharan et al[61] | Cross-sectional study | Israel | Depression | EPDS | ||

| 27 | Shaw et al[43] | Cross-sectional study | United States | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | (1) BDI-II; (2) BAI; and (3) SASRQ |

| 28 | Trumello et al[54] | Longitudinal study | Italy | Depression | (1) State anxiety; and (2) Trait anxiety | (1) EPDS; and (2) STAI-State Y1 and Y2 | |

| 29 | Holditch-Davis et al[44] | Longitudinal study | United States | Depression | State anxiety | Stress | (1) CESD; (2) STAI; (3) PSS: NICU; and (4) PSS:PBC |

| 30 | Mautner et al[55] | Prospective, longitudinal study | Austria | Depression | EPDS | ||

| 31 | Gray et al[28] | Cross-sectional study | Australia | Depression | Parenting stress | (1) EPDS; and (2) PSI-SF | |

| 32 | Gray et al[29] | Cross-sectional study | Australia | Depression | Parenting stress | (1) EPDS; and (2) PSI-SF | |

| 33 | Howe et al[62] | Cross-sectional study | Taiwan | Parenting stress | PSI-Chinese version | ||

| 34 | Miles et al[45] | Longitudinal, descriptive study | United States | Depression | CES-D | ||

| 35 | Mew et al[46] | Correlational analysis | United States | Depression | CES-D | ||

| 36 | Madu and Roos[31] | Cross-sectional study | South Africa | Depression | EPDS | ||

| 37 | Suttora et al[36] | Descriptive study | Italy | (1) PTSD; and (2) Parenting stress | (1) PPQ-Modified version; and (2) PSI-SF | ||

| 38 | Korja et al[56] | Cross-sectional study | Finland | Depression | EPDS | ||

| 39 | Younger et al[47] | Descriptive correlational study | United States | Depression | Stress | (1) CES-D; and (2) MSI | |

| ID | Ref. | Study type | Country | Symptoms | Outcome assessment | NOS score | ||

| 1 | Ballantyne et al[37] | Cross-sectional study | Canada | Depression | Stress | (1) CES-D; and (2) PSS: NICU | ****** (6) | |

| 2 | Baptista et al[48] | Cross-sectional study | Portugal | Psychological problem | Stress | (1) BSI; and (2) Daily hassles questionnaire | ***** (5) | |

| 3 | Barroso et al[38] | Cross sectional study | United States | Depression | EPD-S | ****** (6) | ||

| 4 | Bener[60] | Hospital-based study (Cross sectional study) | Qatar | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | (1) DASS-21; (2) DASS-21; and (3) DASS-21 | ***** (5) |

| 5 | Bouras et al[34] | Cross-sectional study | Greece | Depression | Anxiety | (1) BDI; and (2) STAI | ****** (6) | |

| 6 | Brandon et al[39] | descriptive study | United States | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | (1) EPDS; (2) STAI-S; (3) PPQ; and (4) CHWS | ******* (7) |

| 7 | Carson et al[49] | Cohort study | United Kingdom | Psychological problem | Modified RMI | ***** (5) | ||

| 8 | Cheng et al[13] | Cohort study | United States | Depression | CES-D | ***** (5) | ||

| 9 | Davis et al[57] | Cross-sectional study | Australia | Depression | Stress | (1) EPDS; and (2) DASS | ***** (5) | |

| 10 | Drewett et al[50] | Cross-sectional study | United Kingdom | Depression | EPDS | ***** (5) | ||

| 11 | Edwards et al[58] | Cohort study | Australia | Depression | Parenting stress | (1) EPDS; and (2) PSI | ***** (5) | |

| 12 | Fabiyi et al[40] | Cross-sectional study | United States | (1) State anxiety; and (2) Trait anxiety | STAI | ****** (6) | ||

| 13 | Gambina et al[33] | Case-control study | Italy | Depression | (1) State anxiety; and (2) Trait anxiety | Stress | (1) EPDS; (2) STAI-State and STAI-Trait; and (3) PSM | ****** (6) |

| 14 | Gueron-Sela et al[30] | Cross-sectional study | Israel | Depression | Stress | (1) CES-D; and (2) PSS: NICU | ******* (7) | |

| 15 | Gulamani et al[24] | Cohort study | Pakistan | Depression | EPDS | **** (4) | ||

| 16 | Gungor et al[35] | Case-control study | Turkey | Depression | (1) State anxiety; (2) Trait anxiety | (1) BDI; and (2) STAI | ****** (6) | |

| 17 | Hagan et al[59] | Prospective,randomised, controlled study | Australia | Depression | Anxiety | (1) EPDS; and (2) BDI | ****** (6) | |

| 18 | Henderson et al[51] | Cross-sectional study | United Kingdom | Depression | EPDS | ******* (7) | ||

| 19 | Holditch-Davis et al[44] | Cross-sectional study | United States | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | (1) CES-D; (2) STAI; and (3) PSS: NICU | ****** (6) |

| 20 | Ionio et al[52] | Longitudinal study | Italy | Depression | Profile of mood states | ***** (5) | ||

| 21 | Logsdon et al[41] | Descriptive study | United States | Depression | CES-D | ****** (6) | ||

| 22 | Misund et al[53] | Longitudinal study | Norway | Psychological distress | Anxiety | Trauma-related stress | (1) GHQ likert sum and case sum; (2) STAI-X1; and (3) Impact of Event Scale (IES) | ****** (6) |

| 23 | Misund et al[53] | Cohort study | Norway | Psychological distress | Anxiety | Trauma-related stress | (1) GHQ likert sum and case sum; (2) STAI-X1; and (3) IES | ***** (5) |

| 24 | Pace et al[32] | Longitudinal, prospective, follow-up cohort study | Australia | Depression | Anxiety | (1) CES-D; and (2) Hospital anxiety and depression scale | ****** (6) | |

| 25 | Rogers et al[42] | Cohort study | US | Depression | Anxiety | (1) EPDS; and (2) STAI | ***** (5) | |

| 26 | Sharan et al[61] | Cross-sectional study | Israel | Depression | EPDS | ****** (6) | ||

| 27 | Shaw et al[43] | Cross-sectional study | US | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | (1) BDI-II; (2) BAI; and (3) SASRQ | ****** (6) |

| 28 | Trumello et al[54] | Longitudinal study | Italy | Depression | 1) State anxiety2) Trait anxiety | (1) EPDS; and (2) STAI-State Y1 and Y2 | ******* (7) | |

| 29 | Holditch-Davis et al[44] | Longitudinal study | US | Depression | 1) State anxiety | Stress | (1) CESD; (2) STAI; (3) PSS: NICU; and (4) PSS:PBC | ****** (6) |

| 30 | Mautner et al[55] | Prospective, longitudinal study | Austria | Depression | EPDS | ****** (6) | ||

| 31 | Gray et al[28] | Cross-sectional study | Australia | Depression | Parenting stress | (1) EPDS; and (2) PSI-SF | ****** (6) | |

| 32 | Gray et al[29] | Cross-sectional study | Australia | Depression | Parenting stress | (1) EPDS; and (2) PSI-SF | ****** (6) | |

| 33 | Howe et al[62] | Cross-sectional study | Taiwan | Parenting stress | PSI-Chinese version | ****** (6) | ||

| 34 | Miles et al[45] | Longitudial, descriptive study | United States | Depression | CES-D | ***** (5) | ||

| 35 | Mew et al[46] | Correlational analysis | United States | Depression | CES-D | ***** (5) | ||

| 36 | Madu and Roos[31] | Cross-sectional study | South Africa | Depression | EPDS | ****** (6) | ||

| 37 | Suttora et al[36] | Decriptive study | Italy | (1) PTSD; and (2) Parenting stress | (1) PPQ-Modified version; and (2) PSI-SF | ***** (5) | ||

| 38 | Korja et al[56] | Cross-sectional study | Finland | Depression | EPDS | ****** (6) | ||

| 39 | Younger et al[47] | Decriptive correlational study | United States | Depression | Stress | (1) CES-D; and (2) MSI | ****** (6) | |

| Selection (S) | Comparability (C) | Exposure/outcome E/O | Sub total assessment | Conclusion | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1a | 1b | 1 | 2 | 3 | S1 | C2 | E/O2 | ||

| Ballantyne et al[37] | * | * | No | * | * | * | No | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Baptista et al[48] | * | * | No | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Barroso et al[38] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | No | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Bener[60] | * | No | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Bouras et al[34] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Brandon et al[39] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Carson et al[49] | * | No | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Cheng et al[13] | * | * | No | * | No | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Davis et al[57] | * | * | No | No | * | * | * | * | * | Fair | Good | Good | Good |

| Drewett et al[50] | * | * | * | * | No | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Edwards et al[58] | * | No | No | * | No | * | * | * | * | Fair | Good | Good | Fair |

| Fabiyi et al[40] | * | No | * | No | No | * | * | * | * | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair |

| Gambina et al[33] | * | No | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Gueron-Sela et al[30] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Gulamani et al[24] | * | No | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Gungor et al[35] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Hagan et al[59] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Henderson et al[51] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Holditch-Davis et al[44] | * | * | No | * | No | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Ionio et al[52] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Logsdon et al[41] | * | No | No | * | No | * | * | * | * | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair |

| Misund et al[53] | No | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Misund et al[53] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Pace et al[32] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Rogers et al[42] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Sharan et al[61] | No | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Shaw et al[43] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Trumello et al[54] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Holditch-Davis et al[44] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Mautner et al[55] | * | No | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Gray et al[28] | * | * | No | * | No | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Gray et al[29] | * | * | No | * | No | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Howe et al[62] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Miles et al[45] | * | No | No | * | No | * | * | * | * | Fair | Good | Good | Fair |

| Mew et al[46] | * | No | No | * | No | * | * | No | * | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair |

| Madu and Roos[31] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Suttora et al[36] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Korja et al[56] | * | * | No | * | No | * | * | * | * | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Younger et al[47] | * | No | No | * | No | * | * | * | * | Fair | Good | Good | Good |

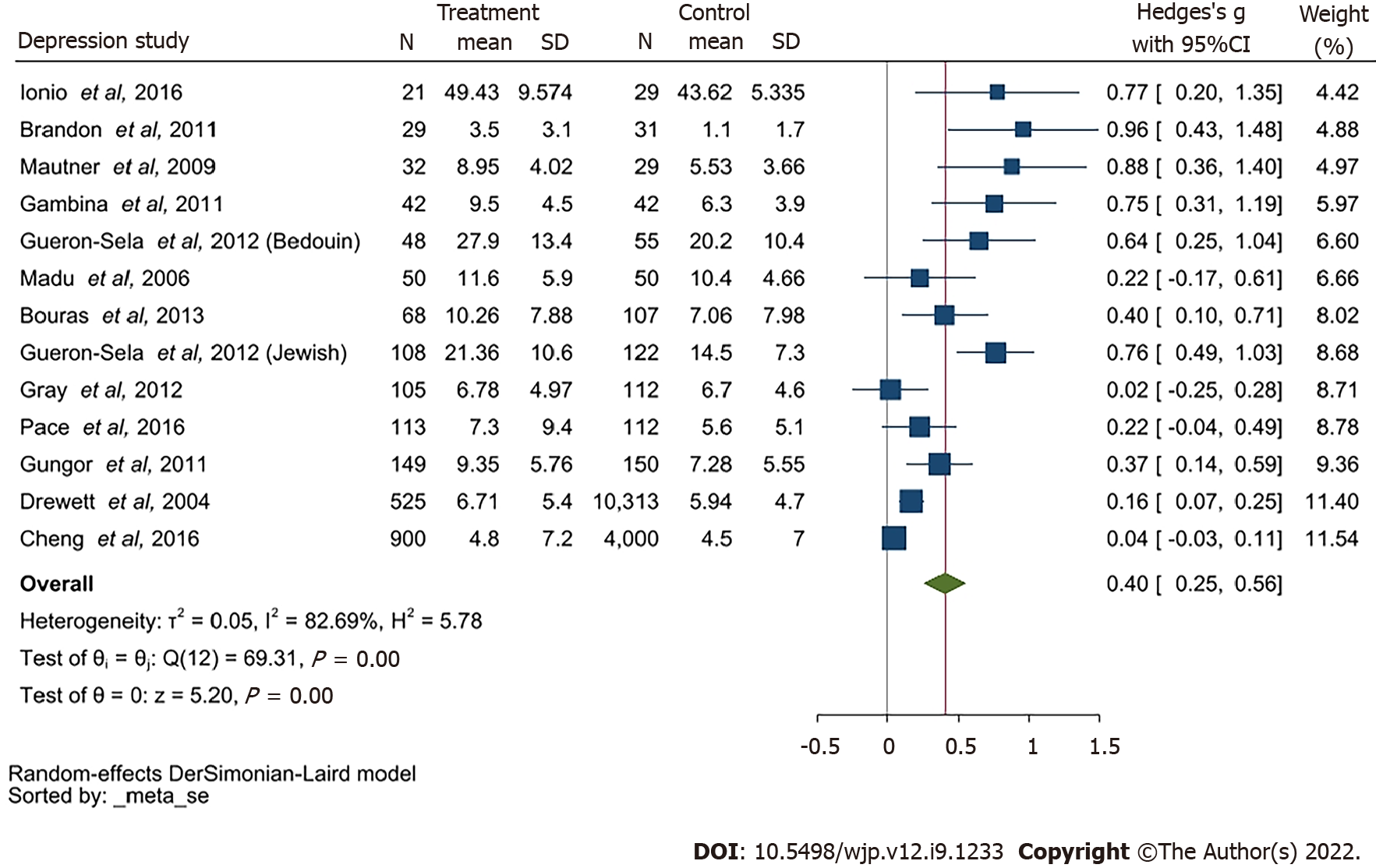

Of the 39 studies, 36 primarily reported an association between the prevalence of depression and PTB. Fifteen studies only examined the differences of non-depressive symptoms as well other factors such as race, ethnicity, plurality across multiple assessment timepoints although, they were not compared to full-term birth mothers of BAME decent. The overall SMD was 0.4 and 95%CI of a range of 0.25-0.56, indicating the prevalence of depression in PTB mothers to be significantly higher than mothers who delivered at term. I2 = 82.69% indicated high heterogeneity among the depression group.

Shaw et al[43] focused on the association between depression symptoms and the efficiency of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), although the specificity of EPDS to the BAME population was not demonstrated. Since most of the studies reported mean and SD, we pooled mean differences and its 95%CI. Seven of the studies lacked information about mean score and SD, thus, were excluded from the meta-analysis. Gray et al[28,29] used the same dataset in two papers, therefore one of these was included into the meta-analysis. Therefore, a total of 12 studies were included in the meta-analysis as indicated by Table 4. Additionally, Gueron-Sela et al[30] studied two ethnicities, therefore it was used twice as reported in Table 4. Therefore, 13 items were reported in the meta-analysis for depression. The meta-analyses for anxiety and stress had 5 studies each, as demonstrated in Tables 5 and 6.

| ID | Ref. | Study type | Country | Sample size | Outcome assessment |

| 1 | Brandon et al[39] | Descriptive study | United States | 60 | EPDS |

| 2 | Bouras et al[34] | Cross-sectional study | Greece | 200 | BDI |

| 3 | Cheng et al[13] | Cohort study | United States | 5350 | CES-D |

| 4 | Drewett et al[50] | Cross-sectional study | United Kingdom | 10838 | EPDS |

| 5 | Gambina et al[33] | Case-control study | Italy | 84 | EPDS |

| 6 | Gray et al[28,29] | Cross-sectional study | Australia | 217 | EPDS |

| 7 | Gueron-Sela et al[30] | Cross-sectional study | Israel | 103 (Bedouin); 230 (Jewish) | CES-D |

| 8 | Gungor et al[35] | Case-control study | Turkey | 299 | BDI |

| 9 | Ionio et al[52] | Longitudinal study | Italy | 50 | Profile of mood states |

| 10 | Madu and Roos[31] | Cross-sectional study | South Africa | 100 | EPDS |

| 11 | Mautner et al[55] | Prospective, longitudinal study | Australia | 61 | EPDS |

| 12 | Pace et al[32] | Longitudinal, prospective cohort study | Australia | 230 | CES-D |

| ID | Ref. | Study type | Country | Sample size | Outcome assessment |

| 1 | Brandon et al[39] | Descriptive study | United States | 60 | STAI-S |

| 2 | Bouras et al[34] | Cross-sectional study | Greece | 200 | STAI-T; STAI-S |

| 3 | Gambina et al[33] | Case-control study | Italy | 84 | STAI-T; STAI-S |

| 4 | Gungor et al[35] | Case-control study | Turkey | 299 | STAI-T; STAI-S |

| 5 | Pace et al[32] | Longitudinal, prospective cohort study | Australia | 230 | HADS-A |

| ID | Ref. | Study type | Country | Sample size | Outcome assessment |

| 1 | Brandon et al[39] | Descriptive study | United States | 60 | PPQ |

| 2 | Gambina et al[33] | Case-control study | Italy | 84 | PSM |

| 3 | Gray et al[28,29] | Cross-sectional study | Australia | 217 | PSI-SF |

| 4 | Howe et al[62] | Cross-sectional study | Taiwan | 420 | PSI-Chinese version |

| 5 | Suttora et al[36] | Descriptive study | Italy | 243 | PSI-SF |

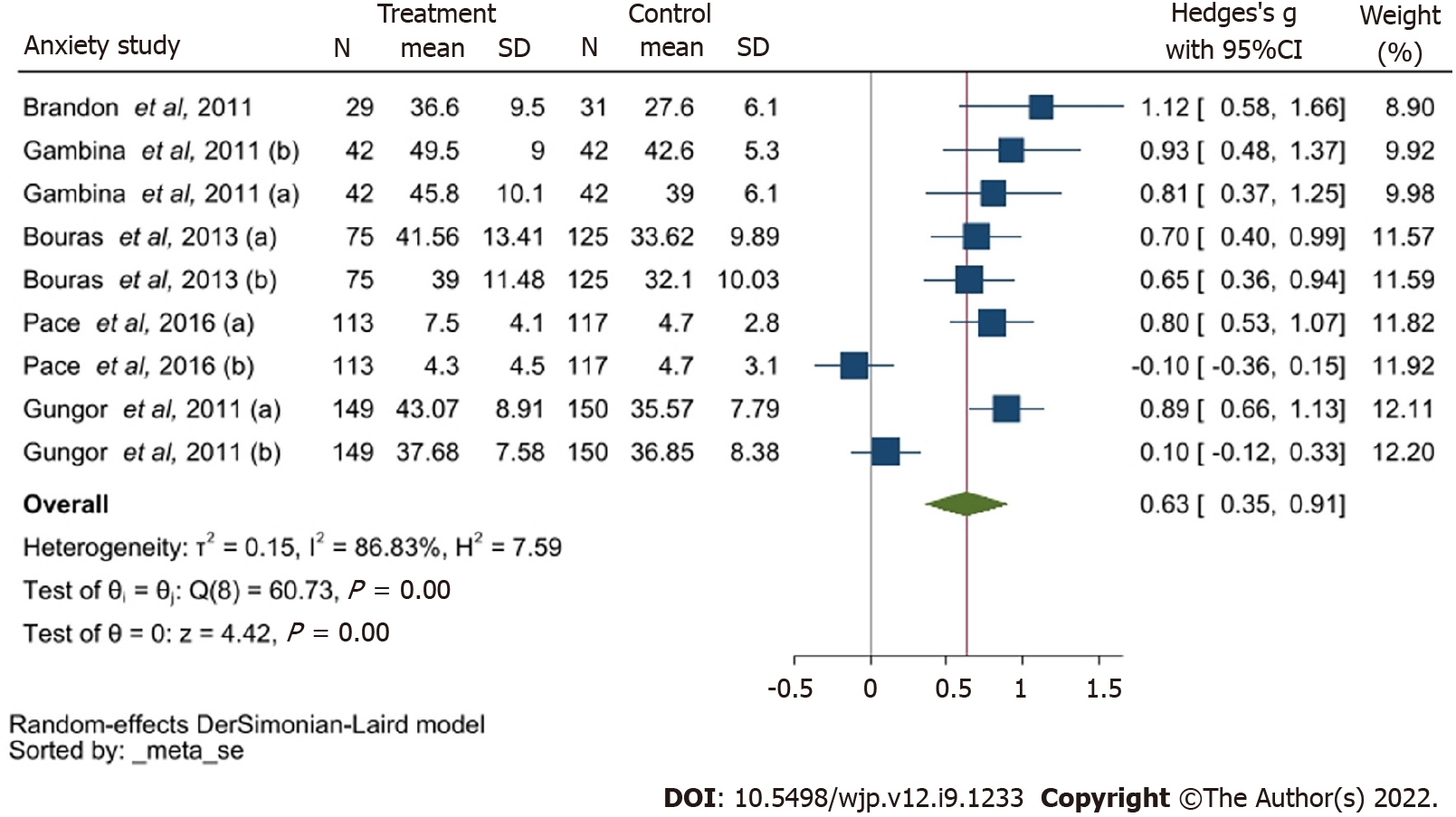

The 12 studies reporting anxiety utilised EDPS, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A), Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression, Beck’s Depression Inventory and Profile of Mood States as their assessment tool. The total scores of these scales are different, and the mean difference of the studies are not compatible. Four studies reported on anxiety using STAI and HADS-A as their mental health assessment of choice. The overall SMD of Anxiety was 0.63 with 95%CI of 0.35-0.91. I2 = 86.83% also indicated high heterogeneity among anxiety group.

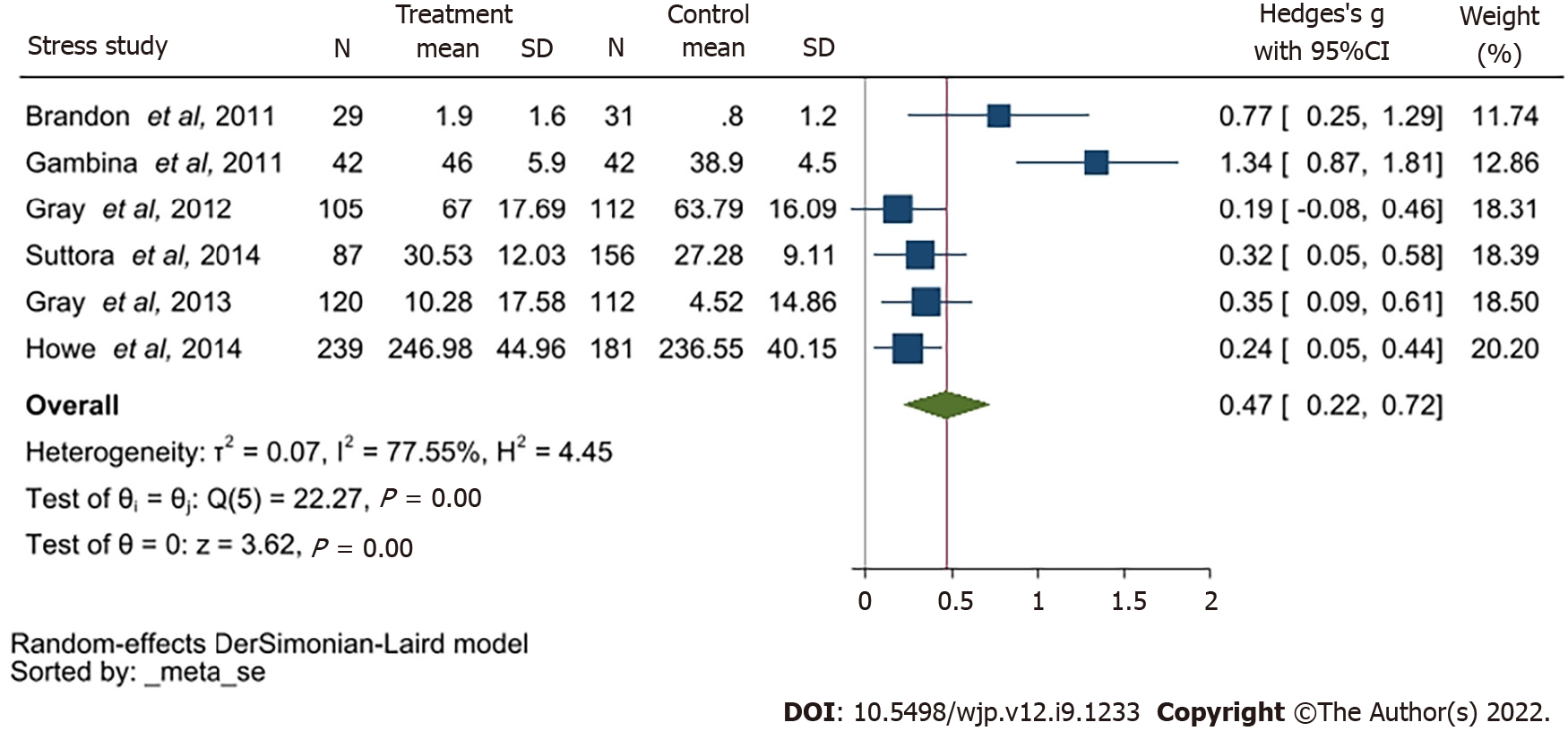

Studies reporting stress used the Parent Stress Index assessment on three separate timepoints along with the Professional Personality Questionnaire and the Perceived Stress Measure. The total scores of these scales in each meta-analysis are different, and the mean difference of the studies are not compatible. The overall SMD of Stress was 0.47 with 95%CI 0.22-0.72. I2 =77.55% indicated high heterogeneity among stress group.

Suttora et al [36] was the only study reporting on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The reported mean and SD of the symptoms of PTSD were transformed to SMD. The SMD was 1.12 with a 95%CI of 0.84-1.40 indicated significantly high PTSD symptoms among BAME PTB women than the term mothers.

Assessment of mental health at differing time-points for depression, anxiety and stress were evaluated between full term and PTB mothers. Different mean scores and SD values were reported across the included studies. The dataset was unified with converting the mean difference to the SMD and demonstrated in the forest plots (Figures 2-4).

This meta-analysis identified depression to be a primary mental health outcome among PTB mothers and significantly higher prevalence rates of depression was reported in PTB mothers compared with full-term mothers.

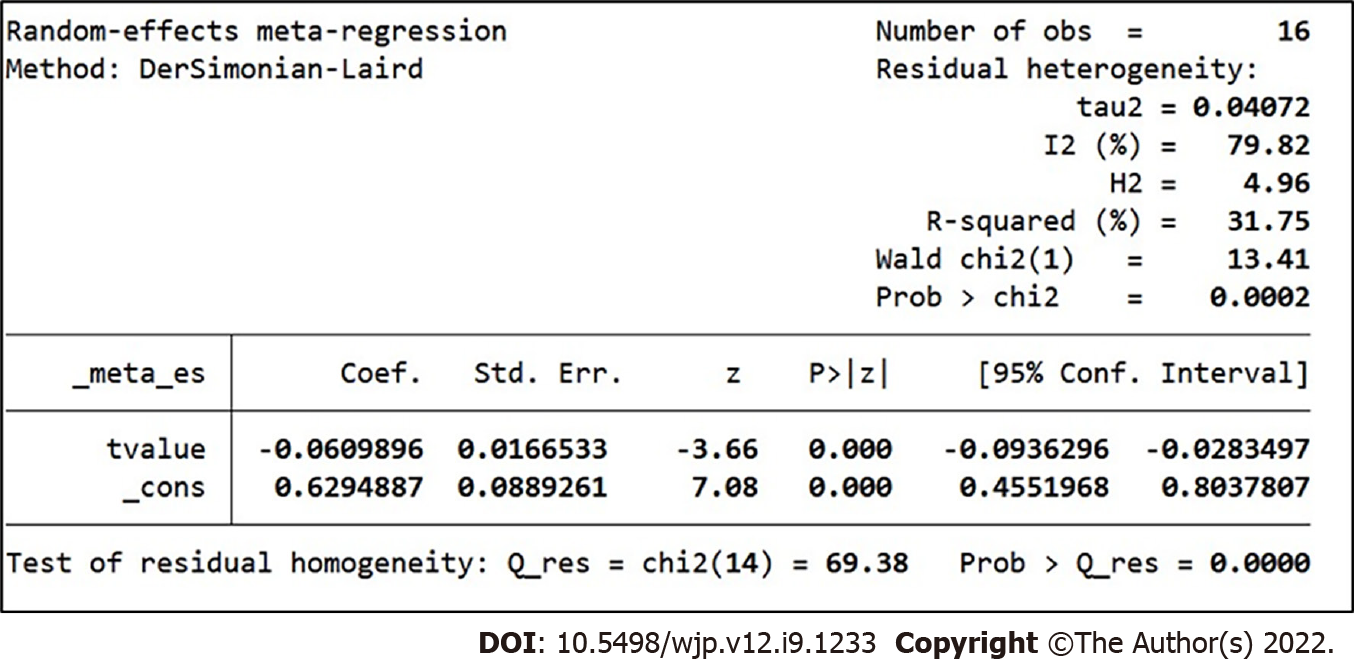

Of the 16 studies included within the meta-regression analysis for depression, 5 reported mean scores and SD of the mental health questionnaires used at parturition. Four studies recorded the mean and SD at 1-mo post-delivery, while another four studies reported the same at 1 mo to 8 mo post-delivery. To eliminate the heterogeneity, these studies were adjusted by timepoints (Figure 5).

The estimated intercept for depression is 0.629 with a 95%CI of 0.455-0.804. This indicates the mental health assessment scores within the PTB group were significantly higher than full-term group at the birth. The coefficient of the covariate time was -0.061 with a 95%CI of -0.094, -0.028 indicating that the coefficients of time were significantly lower than 0. This is indicative of a reduction depression symptoms post-delivery. Heterogeneity decreased from 82.69% to 79.82%, and the differences of assessment time points could explain the 31.75% of the heterogeneity identified.

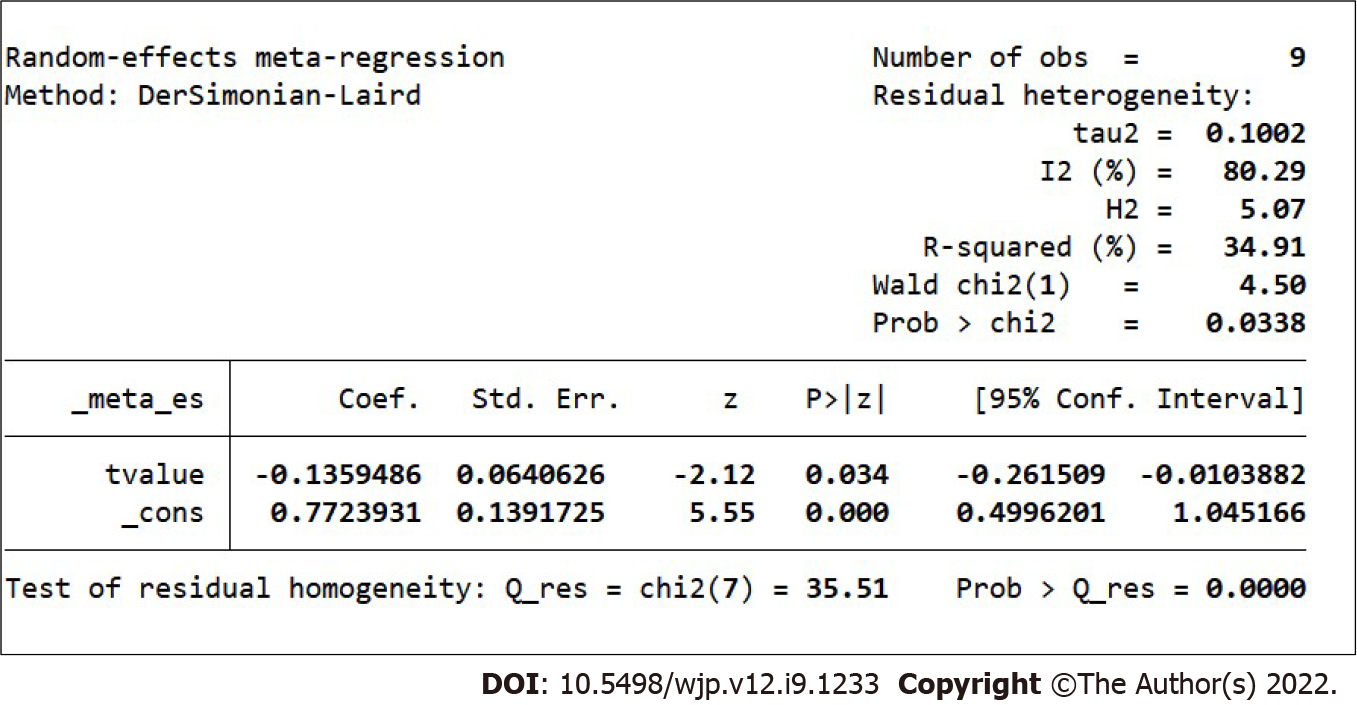

Nine studies that reported anxiety were included in the meta-regression (Figure 6). The estimated intercept was 0.772 with a 95%CI of 0.500-1.045 which indicates the mental health assessment scores of the PTB group are significantly higher than the scores of full-term group. The coefficient of the covariate time is -0.136 with 95%CI of -0.262, -0.010 indicating that the symptoms of anxiety gradually disappeared among PTB group following birth. Heterogeneity reduced from 86.83% to 80.29%. The differing time points in administering the mental health assessment could explain 34.91% of the heterogeneity (Figure 6).

Following the reduction of heterogeneity by way of the meta-regression method, the statistical conclusions demonstrate a statistical significance where the prevalence of depression among BAME women with PTB was higher in comparison to BAME women who delivered at full-term. The I2 was almost 80% which indicates a high heterogeneity.

The pooled SMD within the studies using PTB mothers from United States was 0.46 with a 95%CI of -0.43 – 1.35. The pooled SMD within Australia was 0.44 with a 95%CI of 0.07-0.81. I2 of these two subgroups indicated a high heterogeneity: 91.14% and 87.79% respectively. The assessment timepoints of these two groups have a significant difference, which could be the source of the high heterogeneity. As there were only 2 studies, a meta-regression of the timepoints could not be completed.

A subgroup analysis of depression and anxiety was completed using geographical location as demonstrated in Supplementary Figures 1-3. For depression, the pooled SMD within Greece, Italy, Israel and Turkey was 0.57 with a 95%CI of 0.4-0.74. The pooled SMD within United Kingdom was 0.12 with a 95%CI of 0.03-0.21. I2 was denoted to be indicating a lack of heterogeneity as demonstrated in Supple

Although a meta-regression was not conducted for the pooled SMD within the studies with PTB mothers from United States, a subgroup analysis demonstrated that the high heterogeneity could be attributed to the differences of time points of the mental health assessments.

Of the 39 studies included in the systematic review, thirteen studies were from North America[1,3,6,8,12,19,21,25,27,29,34,35,39], thirteen from Europe[2,5,7,10,13,18,20,22,23,28,30,37,38], six studies from Australia[9,11,17,24,31,32], three from Asia[15,16,33], three from the Middle East[4,14,26] and one from South Africa[36]. These have been demonstrated in Table 1. Depression was the most frequently reported theme across all the studies, followed by anxiety and stress (Table 7). A variety of diagnostic tools were used across the studies, which reflects the diverse clinical practices across different countries.

| Themes | Population group |

| Women who had a preterm birth | |

| Depression | ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ |

| Stress | +++++++++++ |

| Anxiety | +++++++++++ |

| Parenting stress | +++++ |

| State anxiety | +++++ |

| Trait anxiety | ++++ |

| Psychological distress | ++ |

| Trauma-related stress | ++ |

| Psychological problem | ++ |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | + |

Based on the identified data, PTB women from the Mediterranean region (Greece, Italy, Turkey and Israel) may be more prone to depressive symptoms in comparison to BAME women with PTB in Australia and the United States. The pooled odds ratio (OR) and its respective 95%CIs appear credible for PTB BAME women experiencing a significantly higher prevalence of depression post-parturition, although the mental health symptoms appear to reduce over time.

The pooled SMD of anxiety within United States was 1.12 with 95%CI of 0.58-1.66 whilst the pooled SMD of the Mediterranean region (Greece, Italy, Turkey) was 0.66 with a 95%CI of 0.37-0.95. The pooled SMD of Australia was 0.35 with a 95%CI of -0.54 -1.23 (Supplementary Figure 2). BAME women with PTB from Australia appear to have less symptoms of anxiety and the main source of the high heterogeneity in subgroup was still from the time points.

In relation to assessing stress, Gray et al[28,29] conducted mental health assessments at months 4 and 12, post-parturition. Whilst this appears to be useful follow-up data to evaluate, the outcome measures were analysing 2 different mental health variables of parenting stress and general stress. As shown in Supplementary Figure 4 four studies reported on parenting stress and 2 of them reported on the overall state of stress. The subgroup analysis conducted indicated a lack of heterogeneity between these studies. Mild heterogeneity was identified within the studies included in the stress group alone. The pooled SMD within the parenting group was 0.27 with a 95%CI of 0.15-0.39. In the stress group, the pooled SMD was 1.07 with a 95%CI of 0.51-1.62. Additionally, the symptoms of parenting stress were less severe within the PTB group (Table 7 and Supplementary Figures 4 and 5).

Studies reporting depression[32] demonstrated women with severe PTB indicated a high SMD at parturition indicating elevated levels of depressive symptoms (Supplementary Figure 6). A combination of worries about very premature babies and the trauma following parturition may further attribute to elevated depressive symptoms. Only Pace et al’s study conducted the assessment of questionnaires among the very PTB women group at the birth[32]. Women with a more severe PTB may indicate higher scores of depression, therefore this study was excluded from the sensitivity analysis. After removing Pace et al’s study, the heterogeneity in Australia reduced from an I2 of 87.79% to 52.99%[32]. Therefore, conclusions were adjusted from a pooled SMD of 0.42 (with 95%CI: 0.28-0.56) to 0.34 (with 95%CI: 0.22-0.46). Despite this numerical change, an elevated level of depression among BAME PTB women were visible in comparison to those with a full-term pregnancy (Supplementary Figure 6).

Based on the anxiety studies, Gungor et al[35] in particular, reported extremely small OR and a sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding one possible outlier study, as indicated by Supple

For studies with a small sample size, the pooled OR is significantly higher based on the funnel plots, therefore, these would be prone to publication bias. To assess this further, Egger’s tests were conducted for all studies included within the meta-analysis.

Funnel plots developed within this sample intuitively revealed publication bias (Supple

Based on the findings demonstrated in Supplementary Figures 11, 3 further studies were imputed to correct the effect size of small studies. The small study effect was eliminated with using the imputation method, and publication bias was corrected (demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 12). The Hedge’s g (Supplementary Figure 12) was significantly higher than 0 among the meta-analysis based and imputed studies. After imputing the 3 new studies and removing the publication bias, the statistical conclusion was adjusted from a SMD of 0.4 with 95%CI of 0.25-0.56 to 0.32 (95%CI of 0.18-0.47). Despite the adjustments of publication bias, there was significant evidence that the prevalence of depression among BAME PTB women were higher than those who gave birth at full-term (Supplementary Figures 12 and 13).

Egger’s test P value for anxiety was 0.198, indicating no publication bias exists (demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 14). Egger’s test P value for stress was 0.036, indicating a slight publication bias among the studies (demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 15).

Ascertainment bias was considered within the context of the meta-analysis. Due to the lack of required details such as the proportion of different ethnic groups and mental health assessments, it was not possible to assess this numerically. However, within the context of all the studies included in the systematic review portion of the study, it is evident, there could be ascertainment bias as the sampling methods used in the studies comprise of patients who may or may not have a higher or lower probability of reporting mental health symptomatologies. These studies may be subjected to selection bias due to the lack of consistency around frequency of administering the relevant mental health instruments. In essence, studies should have had samples with all ethnicities and races (including Caucasians) to better evaluate the true mental health impact due to PTB. Furthermore, the sample population should have received a standardised set of mental health assessments to determine anxiety, depression, PTSD and other mental illnesses at specific time points during the pre and post-natal period since it is common to have undiagnosed mental health conditions. In addition to this, some studies have had attempted to evaluate the mental health impact after birth at 8 mo although this lacks scientific justification and thereby, epidemiologically insignificant. Furthermore, due to the lack of consistency in assessing and reporting mental health outcomes post-natally, attrition bias may be present. However, a definitive conclusion could not be attained numerically due to limitations in the sample sizes reported.

In this meta-analysis, the prevalence rate of depression among PTB BAME mothers was identified to be significantly higher than in full-term mothers with an OR of 1.50 and 95%CI of 29%-74%. Depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers of premature infants were frequently reported in the post-natal period[13]. There may be many causes for this including the social support. Cheng et al[13] reported that mothers with non-resident fathers experienced higher rates of depressive symptoms, as did the non-resident fathers included in this study. Lack of social support is likely to be further exacerbated by prolonged hospitalisation of preterm infants and the unique challenges faced by infants the premature following hospital discharge. Additionally, mothers may be admitted to hospital prior to delivery, in some cases for weeks, due to conditions like severe preeclampsia or PROM associated with PTB and hence they may be more isolated than mothers of term infants.

This study defined three sub-groups; assessment timepoint < 1 mo, 1-8 mo and > 8 mo, and indicated that shorter the time after giving birth, the more significant was the depression. Therefore, the provision of mental health support following the immediate post-partum period would benefit patients. Within the first month after delivery, depressive symptoms were significant among PTB mothers; however, by 8 mo and after 8 mo, the increased prevalence of depression was only slightly significant among PTB mothers (OR of 1.17 with 95%CI of 8%-27%; OR of 1.06 with a CI of 1%-12%).

Separation of the infant and the mother is an important and frequent occurrence in PTB, which may explain why mothers of preterm infants are at increased risk of depression. Furthermore, maternal co-morbidities including preeclampsia or recovery from an obstetrics intervention such as a caesarean section may also impact on a mother’s ability to bond with her new-born, who maybe in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or special care unit. One study from South Africa[31] demonstrated a high prevalence of depression in mothers of both full term and preterm infants from lower socioeconomic groups. Women from lower socioeconomic groups are likely exposed to greater stressors relevant to the scarcity of resources[31], affecting their mental health.

Adjusting to parenthood is important for all parents. In the case of PTB mothers may not have sufficient time to prepare, which may lead to maternal stress[47]. Familiarity with the situation, possibly by having had a previous preterm infant, and predictability of birth outcome have been found to reduce stress and anxiety[47]. Medically indicated preterm delivery may have been planned, for example, in multiple pregnancies or mothers with diabetes and thus, predictable. Therefore, it is possible that those mothers experience less stress than those who give birth following an acute spontaneous onset preterm labor. In addition to mental preparation, the former group of parents of preterm infants may have had time to visit the NICU and speak with neonatologists to gain further information and this may reduce anxiety following birth.

Parenting stress is found to be higher in mothers of preterm infants at one year[29]. This relationship may by predicted by maternal depression as well as impaired parent and infant interactions[29]. Interestingly, parenting stress is not significantly different in mothers of preterm or full-term infants in early infancy[28], suggesting all mothers require support in the immediate post-partum period to reduce parental mental health but prolonged provision of such support is important in managing PTB mothers.

Increased and unexpected medical interventions associated with PTB, including painful corticosteroid injections or the use of magnesium sulphate. Mothers may have additional intimate examinations and the need for emergency procedures such as caesarean sections, which may negatively impact a mother’s physical and mental health. These may exacerbate the underlying stress faced by a PTB mother and her partner; their feelings of anxiety and stress are compounded in some circumstances by the lack of preparedness and loss of control. Together, these experiences may explain why mothers and fathers of preterm infants have greater levels of stress[29] and depression[13].

Cheng et al[13] conducted the comparison between fathers and mothers suffering as a result of PTB among Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black and Non-Hispanic as well as other races. Gueron-Sela et al[30] on the other hand focused on depression and stress symptomatologies among Bedouin and Jewish women. Based on Gueron-Sela et al’s findings, Bedouin women experienced the highest level of depression[30]. In comparison to these, Rogers et al[42] compared the Caucasian and African American PTB patients that indicated a lack of significant differences between the two groups. Ballantyne et al[37] conducted their study on Canadian PTB women which included immigrant women. However, immigrant’s status had no contribution to the differences in mental health disorders or symptomatologies.

The mental health impact on those with PTB could be exacerbated due to understandable feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, and low mood is commonly reported by these women. On the contrary, Jotzo and Poets[14] demonstrated PTB could lead to traumatising effects on parents with 49% of mothers reporting traumatic reactions even after a year. Muller-Nix et al[15] demonstrated this correlation of traumatic stress and psychological distress between mother and child. Pierrehumbert et al[16] indicated post-traumatic stress symptoms after PTB was a predictor of a child’s eating and sleeping problems. Similarly, Solhaug et al[17] found that parents, who had hospital stays following a PTB requiring NICU, demonstrated high levels of psychological reactions that required treatment.

Perinatal mental health around suicidality or suicidal ideation should be considered as a priority to be addressed among BAME women, which is vital in particular within the United Kingdom. BAME women are at a higher risk of suffering from mental health disorder in comparison to Caucasian women in the United Kingdom and they are less likely to access healthcare support. This is particularly true for women of Pakistani and Indian background. Additionally, Anderson et al[63] reported prevalence and risk of mental health disorders among migrant women. These factors should be considered by those treating clinical groups. In addition to the timepoint, we also considered the impact of population. It remains unclear whether the prevalence rate of depression varies after PTB in different ethnic groups. Gulamani et al[64] have found the depressive symptoms of women with PTB may be associated with race and culture, but further evidence is lacking. Due to the higher risk of mental health symptoms around the time of PTB, this data may help the health service providers to focus on delivering timely support to the BAME mothers with PTB.

Interestingly, alcohol consumption and substance abuse that are linked to worsening of mental health and poor pregnancy outcomes were not identified within the literature pertinent to BAME population in the scope of this study[65-70].

Similarly, substance abuse among pregnant women increases the risk of PTB and the association of mental illness among the BAME population[71,72]. Holden et al[72] demonstrated self-reported depressive symptoms associated with a group of 602 BAME and Caucasian pregnant women that had substance abuse and were subjected to intimate partner violence. This study used the EPDMS which demonstrated elevated levels of depressive illness that required clinical diagnoses and treatments at a mental health care facility. Additionally, women abuse screening tool was used to evaluate relationship issues and those needing appropriate support was referred to social services[71,72]. There is limited information available around substance abuse and partner violence associated with mental health among BAME women. Research conducted within this area appears to lack consistency and this makes systematic evaluation of cultural paradigms relevant to BAME women and the direct association with PTB and mental health difficult, given the complexity of these issues.

Heterogeneity of studies gathered within this review challenged the evidence synthesis. Studies identified reported on mental health outcomes without a clear distinction mostly between mental health symptomatologies and psychiatric comorbidities. Timelines for administering mental health instruments and other tools such as talking therapies were not unified across all studies. Collectively, these are design and methodological flaws influencing heterogeneity. Studies were excluded if they discussed quality of life as this does not demonstrate the identification or reporting of mental health outcomes such as pre or postnatal depression, anxiety, psychosis and other mood disorders.

PTB has a significant association with depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in new mothers during the immediate postpartum period. The mental health symptoms are more significant in very preterm mothers than non-very preterm mothers. However, the effect of PTB on the incidence of depression and other mental health outcomes is unclear among different ethnic groups and therefore more studies are needed to explore this.

This study identified a methodological gap to evaluate disease sequelae between PTB and mental health among BAME populations. This important facet should be considered in future research studies, which requires the involvement of multidisciplinary teams. Most included studies did not indicate a publicly available protocol, and availability of such would have assisted in reducing potential biases during study selection in this systematic review to improve sampling techniques and the subsequent data analysis. Future PTB research will be benefited by Population Intervention (s) Comparator and Outcome (s) based reporting to address true mental health impact within BAME populations. The evidence gap that exists from multi-stakeholder needs to be filled to improving patient care. The development of a classification framework for healthcare systems to better assess BAME women at risk with PTB and mental health outcomes would be beneficial. Including cultural adaptation methods as well as training of healthcare professionals will help to manage patients’ expectations with the required sensitivities. Similarly, cost-effectiveness and long-term sustainability should be considered when developing a suitable framework.

It is also vital to acknowledge health inequalities and avoidable disparities should be addressed as a matter of urgency. Maternal care should have integrated methods of working with mental health care professionals and a culturally adapted and sensitive specialist service to support BAME women after a PTB may improve the patient outcomes. It is important to improve quality of care received by vulnerable BAME women such as those who are refugees or migrants and do not speak English. Equally, mental health services should work more cohesively within the women’s health in the community setting and training should be offered to all healthcare professionals to provide a personalised care.

Preterm birth (PTB) is a complex clinical condition contributing to significant maternal morbidity and a leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality. Therefore, potential mental health impact of PTB on women is an important clinical and social sequel that requires further understanding.

Existing research primarily reports the mental health impact of women with PTB within the Caucasian population. There remains a paucity of research on the ethnic minority populations. Thus, we aimed to assess the current research gap relevant to ethnic minorities to inform future research that could aid with improving patient and clinical reported outcomes.

(1) We aimed to describe the prevalence of mental health conditions and/or symptoms reported by women with PTB experiences within the ethnic minorities; and (2) We also extended our study to report the commonly used methods of mental health assessments to charactertise the identified mental health conditions and/or symptoms with the pooled sample.

A systematic methods protocol was developed, peer reviewed and published in PROSPERO (CRD42040210863). Multiple databases were used to extract relevant data for a meta-analysis. A trim and fill method was used to report publication bias in addition to an Egger’s test. I2 was used to report heterogeneity.

From a total of 3516 studies identified, we included 39 studies that met the inclusion criteria. Depression was the most commonly reported mental illness among PTB mothers in comparison to those who had a full-term pregnancy. The subgroup analysis demonstrated depression to be time-sensitive relative to the PTB. Stress and anxiety were also prevalent among PTB mothers as opposed to full-term mothers.

There appears to be a mental health impact among PTB mothers from ethnic minorities. This is an important aspect to consider for maternity care services to improve the quality care provided to PTB women.

Future researchers should consider inclusion of all ethnicities and races to ensure generalizability of any findings to all mothers that could truly improve maternity care services.

The authors acknowledge support from Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, University College London and Liverpool Women’s hospital. We would like to acknowledge Mrs Haque N who inspired the discussion of BAME groups within the context of this study. This paper is part of the multifaceted ELEMI project that is sponsored by Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust and in collaboration with the University of Liverpool, Liverpool Women’s Hospital, University College London, University College London NHS Foundation Trust, University of Southampton, Robinson Institute-University of Adelaide, Ramaiah Memorial Hospital (India), University of Geneva and Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Nursing & Midwifery Council (NMC), 98I1393; British Association for Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP), 060632.

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chakrabarti S, India; Ng QX, Singapore S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu RR

| 1. | Misund AR, Nerdrum P, Diseth TH. Mental health in women experiencing preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371:261-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1836] [Cited by in RCA: 1966] [Article Influence: 115.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen KH, Chen IC, Yang YC, Chen KT. The trends and associated factors of preterm deliveries from 2001 to 2011 in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e15060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Manuck TA. Racial and ethnic differences in preterm birth: A complex, multifactorial problem. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:511-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schaaf JM, Liem SM, Mol BW, Abu-Hanna A, Ravelli AC. Ethnic and racial disparities in the risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:433-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Hassan S, Erez O, Chaiworapongsa T, Mazor M. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113 Suppl 3:17-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1046] [Cited by in RCA: 974] [Article Influence: 51.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sheikh IA, Ahmad E, Jamal MS, Rehan M, Assidi M, Tayubi IA, AlBasri SF, Bajouh OS, Turki RF, Abuzenadah AM, Damanhouri GA, Beg MA, Al-Qahtani M. Spontaneous preterm birth and single nucleotide gene polymorphisms: a recent update. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ehn NL, Cooper ME, Orr K, Shi M, Johnson MK, Caprau D, Dagle J, Steffen K, Johnson K, Marazita ML, Merrill D, Murray JC. Evaluation of fetal and maternal genetic variation in the progesterone receptor gene for contributions to preterm birth. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:630-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Manuck TA, Major HD, Varner MW, Chettier R, Nelson L, Esplin MS. Progesterone receptor genotype, family history, and spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:765-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Manuck TA, Lai Y, Meis PJ, Dombrowski MP, Sibai B, Spong CY, Rouse DJ, Durnwald CP, Caritis SN, Wapner RJ, Mercer BM, Ramin SM. Progesterone receptor polymorphisms and clinical response to 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:135.e1-135.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li Y, Quigley MA, Macfarlane A, Jayaweera H, Kurinczuk JJ, Hollowell J. Ethnic differences in singleton preterm birth in England and Wales, 2006-12: Analysis of national routinely collected data. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33:449-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Public Health England. Maternity high impact area: Reducing the inequality of outcomes for women from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities and their babies. Public Health England. [cited 8 April 2021]. In: Public Health England [Internet]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/942480/Maternity_high_impact_area_6_Reducing_the_inequality_of_outcomes_for_women_from_Black__Asian_and_Minority_Ethnic__BAME__communities_and_their_babies.pdf. |

| 13. | Cheng ER, Kotelchuck M, Gerstein ED, Taveras EM, Poehlmann-Tynan J. Postnatal Depressive Symptoms Among Mothers and Fathers of Infants Born Preterm: Prevalence and Impacts on Children's Early Cognitive Function. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016;37:33-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jotzo M, Poets CF. Helping parents cope with the trauma of premature birth: an evaluation of a trauma-preventive psychological intervention. Pediatrics. 2005;115:915-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Muller-Nix C, Forcada-Guex M, Pierrehumbert B, Jaunin L, Borghini A, Ansermet F. Prematurity, maternal stress and mother-child interactions. Early Hum Dev. 2004;79:145-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pierrehumbert B, Nicole A, Muller-Nix C, Forcada-Guex M, Ansermet F. Parental post-traumatic reactions after premature birth: implications for sleeping and eating problems in the infant. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F400-F404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Solhaug M, Bjørk IT, Sandtrø HP. Staff perception one year after implementation of the the newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program (NIDCAP). J Pediatr Nurs. 2010;25:89-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1399] [Cited by in RCA: 1256] [Article Influence: 83.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sanchez SE, Puente GC, Atencio G, Qiu C, Yanez D, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Risk of spontaneous preterm birth in relation to maternal depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms. J Reprod Med. 2013;58:25-33. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Staneva A, Bogossian F, Pritchard M, Wittkowski A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: A systematic review. Women Birth. 2015;28:179-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Grigoriadis S, Graves L, Peer M, Mamisashvili L, Tomlinson G, Vigod SN, Dennis CL, Steiner M, Brown C, Cheung A, Dawson H, Rector NA, Guenette M, Richter M. Maternal Anxiety During Pregnancy and the Association With Adverse Perinatal Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fekadu Dadi A, Miller ER, Mwanri L. Antenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ghimire U, Papabathini SS, Kawuki J, Obore N, Musa TH. Depression during pregnancy and the risk of low birth weight, preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction- an updated meta-analysis. Early Hum Dev. 2021;152:105243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gulamani SS, Premji SS, Kanji Z, Azam SI. Preterm birth a risk factor for postpartum depression in Pakistani women. Open J Depress. 2013;2:72-81. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hedges LV. Distribution Theory for Glass's Estimator of Effect Size and Related Estimators. J Educ Stat. 1981;6:107-128. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 704] [Cited by in RCA: 707] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hedges LV. Estimation of effect size from a series of independent experiments. Psychol Bull. 1982;92:490-499. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1985. |

| 28. | Gray PH, Edwards DM, O'Callaghan MJ, Cuskelly M. Parenting stress in mothers of preterm infants during early infancy. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gray PH, Edwards DM, O'Callaghan MJ, Cuskelly M, Gibbons K. Parenting stress in mothers of very preterm infants -- influence of development, temperament and maternal depression. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:625-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gueron-Sela N, Atzaba-Poria N, Meiri G, Marks K. Prematurity, ethnicity and personality: risk for postpartum emotional distress among Bedouin-Arab and Jewish women. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2013;31:81-93. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Madu SN, Roos JJ. Depression among mothers with preterm infants and their stress-coping strategies. Soc Behav Personality: Int J. 2006;34:877-890. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pace CC, Spittle AJ, Molesworth CM, Lee KJ, Northam EA, Cheong JL, Davis PG, Doyle LW, Treyvaud K, Anderson PJ. Evolution of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Parents of Very Preterm Infants During the Newborn Period. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:863-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gambina I, Soldera G, Benevento B, Trivellato P, Visentin S, Cavallin F, Trevisanuto D, Zanardo V. Postpartum psychosocial distress and late preterm delivery. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2011;29:472-479. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bouras G, Theofanopoulou N, Mexi-Bourna P, Poulios A, Michopoulos I, Tassiopoulou I, Daskalaki A, Christodoulou C. Preterm birth and maternal psychological health. J Health Psychol. 2015;20:1388-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gungor I, Oskay U, Beji NK. Biopsychosocial risk factors for preterm birth and postpartum emotional well-being: a case-control study on Turkish women without chronic illnesses. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:653-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Suttora C, Spinelli M, Monzani D. From prematurity to parenting stress: The mediating role of perinatal post-traumatic stress disorder. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2014;11:478-493. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ballantyne M, Benzies KM, Trute B. Depressive symptoms among immigrant and Canadian born mothers of preterm infants at neonatal intensive care discharge: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13 Suppl 1:S11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Barroso NE, Hartley CM, Bagner DM, Pettit JW. The effect of preterm birth on infant negative affect and maternal postpartum depressive symptoms: A preliminary examination in an underrepresented minority sample. Infant Behav Dev. 2015;39:159-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Brandon DH, Tully KP, Silva SG, Malcolm WF, Murtha AP, Turner BS, Holditch-Davis D. Emotional responses of mothers of late-preterm and term infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40:719-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Fabiyi C, Rankin K, Norr K, Shapiro N, White-Traut R. Anxiety among Black and Latina Mothers of Premature Infants at Social-Environmental Risk. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2012;12:132-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Logsdon MC, Davis DW, Birkimer JC, Wilkerson SA. Predictors of Depression in Mothers of Preterm Infants. J Soc Behav Personality. 1997;12:73-88. |

| 42. | Rogers CE, Kidokoro H, Wallendorf M, Inder TE. Identifying mothers of very preterm infants at-risk for postpartum depression and anxiety before discharge. J Perinatol. 2013;33:171-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Shaw RJ, Sweester CJ, St John N, Lilo E, Corcoran JB, Jo B, Howell SH, Benitz WE, Feinstein N, Melnyk B, Horwitz SM. Prevention of postpartum traumatic stress in mothers with preterm infants: manual development and evaluation. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2013;34:578-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Holditch-Davis D, Santos H, Levy J, White-Traut R, O'Shea TM, Geraldo V, David R. Patterns of psychological distress in mothers of preterm infants. Infant Behav Dev. 2015;41:154-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D, Schwartz TA, Scher M. Depressive symptoms in mothers of prematurely born infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28:36-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Mew AM, Holditch-Davis D, Belyea M, Miles MS, Fishel A. Correlates of depressive symptoms in mothers of preterm infants. Neonatal Netw. 2003;22:51-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Younger JB, Kendell MJ, Pickler RH. Mastery of stress in mothers of preterm infants. J Soc Pediatr Nurs. 1997;2:29-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Baptista J, Moutinho V, Mateus V, Guimarães H, Clemente F, Almeida S, Andrade MA, Dias CP, Freitas A, Martins C, Soares I. Being a mother of preterm multiples in the context of socioeconomic disadvantage: perceived stress and psychological symptoms. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Carson C, Redshaw M, Gray R, Quigley MA. Risk of psychological distress in parents of preterm children in the first year: evidence from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Drewett R, Blair P, Emmett P, Emond A; ALSPAC Study Team. Failure to thrive in the term and preterm infants of mothers depressed in the postnatal period: a population-based birth cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:359-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Henderson J, Carson C, Redshaw M. Impact of preterm birth on maternal well-being and women's perceptions of their baby: a population-based survey. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ionio C, Colombo C, Brazzoduro V, Mascheroni E, Confalonieri E, Castoldi F, Lista G. Mothers and Fathers in NICU: The Impact of Preterm Birth on Parental Distress. Eur J Psychol. 2016;12:604-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Misund AR, Nerdrum P, Bråten S, Pripp AH, Diseth TH. Long-term risk of mental health problems in women experiencing preterm birth: a longitudinal study of 29 mothers. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Trumello C, Candelori C, Cofini M, Cimino S, Cerniglia L, Paciello M, Babore A. Mothers' Depression, Anxiety, and Mental Representations After Preterm Birth: A Study During the Infant's Hospitalization in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Front Public Health. 2018;6:359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Mautner E, Greimel E, Trutnovsky G, Daghofer F, Egger JW, Lang U. Quality of life outcomes in pregnancy and postpartum complicated by hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes, and preterm birth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;30:231-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Korja R, Savonlahti E, Ahlqvist-Björkroth S, Stolt S, Haataja L, Lapinleimu H, Piha J, Lehtonen L; PIPARI study group. Maternal depression is associated with mother-infant interaction in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:724-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Davis L, Edwards H, Mohay H, Wollin J. The impact of very premature birth on the psychological health of mothers. Early Hum Dev. 2003;73:61-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Edwards DM, Gibbons K, Gray PH. Relationship quality for mothers of very preterm infants. Early Hum Dev. 2016;92:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hagan R, Evans SF, Pope S. Preventing postnatal depression in mothers of very preterm infants: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2004;111:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Bener A. Psychological distress among postpartum mothers of preterm infants and associated factors: a neglected public health problem. Braz J Psychiatry. 2013;35:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Sharan H, Kaplan B, Weizer N, Sulkes J, Merlob P. Early screening of postpartum depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2006;18:213-218. |

| 62. | Howe TH, Sheu CF, Wang TN, Hsu YW. Parenting stress in families with very low birth weight preterm infants in early infancy. Res Dev Disabil. 2014;35:1748-1756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Anderson FM, Hatch SL, Comacchio C, Howard LM. Prevalence and risk of mental disorders in the perinatal period among migrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20:449-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Gulamani SS, Premji SS, Kanji Z, Azam SI. A review of postpartum depression, preterm birth, and culture. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2013;27:52-9; quiz 60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | NHS Digital. Health Survey for England – 2012. [cited 8 April 2021]. In: NHS Digital [Internet]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/health-survey-for-england-2012. |

| 66. | von Hinke Kessler Scholder S, Wehby GL, Lewis S, Zuccolo L. Alcohol Exposure In Utero and Child Academic Achievement. Econ J (London). 2014;124:634-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | The Royal College of Midwives. Alcohol and pregnancy guidance paper. [cited 8 April 2021]. In: The Royal College of Midwives [Internet]. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/HIR/378336. |

| 68. | Schölin L, Watson J, Dyson J, Smith L. Alcohol Guidelines For Pregnant Women: Barriers and enablers for Midwives to deliver advice. [cited 8 April 2021]. In: The Institute of Alcohol Studies [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/IAS%20reports/rp37092019.pdf. |