Published online Mar 19, 2022. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i3.494

Peer-review started: September 6, 2021

First decision: December 27, 2021

Revised: January 5, 2022

Accepted: February 16, 2022

Article in press: February 16, 2022

Published online: March 19, 2022

Processing time: 193 Days and 5.7 Hours

Previous studies have shown that personality traits are associated with self-harm (SH) in adolescents. However, the role of resilience in this association remains unclear. Our research aims to explore the hypothesized mediation effect of resilience in the relationship between personality traits and SH in Chinese children and adolescents.

To evaluate resilience as a mediator of the association between personality traits and SH.

A population-based cross-sectional survey involving 4471 children and adolescents in Yunnan province in southwestern China was carried out. Relevant data were collected by self-reporting questionnaires. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were employed to identify associated factors of SH. A path model was used to assess the mediation effect of resilience with respect to personality traits and SH association.

Among the 4471 subjects, 1795 reported SH, with a prevalence of 40.1% (95%CI: 34.4%-46.0%). All dimensions of personality traits were significantly associated with SH prevalence. Resilience significantly mediated the associations between three dimensions of personality (extroversion, neuroticism, psychoticism) and SH, accounting for 21.5%, 4.53%, and 9.65%, respectively, of the total associations. Among all dimensions of resilience, only emotional regulation played a significant mediation role.

The results of the study suggest that improving emotion regulation ability might be effective in preventing personality-associated SH among Chinese children and adolescents.

Core Tip: In children and adolescents, personality traits are closely related to self-harm (SH) behaviors. In this cross-sectional study of 4471 Chinese children and adolescents, we detected a significant role of resilience in the association between personality traits and SH. Further, among all dimensions of resilience, only emotion regulation mediated the association between personality and SH. Improving emotion regulation ability could reduce the occurrence of SH in Chinese children and adolescents.

- Citation: Jiao XY, Xu CZ, Chen Y, Peng QL, Ran HL, Che YS, Fang D, Peng JW, Chen L, Wang SF, Xiao YY. Personality traits and self-harm behaviors among Chinese children and adolescents: The mediating effect of psychological resilience. World J Psychiatry 2022; 12(3): 494-504

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v12/i3/494.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i3.494

Self-harm (SH) refers to the behavior of harming one’s own body with or without the intention of suicide[1]. SH is a global health concern. Among all age groups, the highest risk of SH has been reported in the adolescent population, and the lifetime prevalence of SH in non-Western countries was found to be higher than that in Western countries[2]. A meta-analysis found that the prevalence of SH among Chinese adolescents has reached 22.37%[3]. SH is the most prominent risk factor of future suicide[4]. Considering the high prevalence of SH among adolescents, together with the intimate relationship between SH and suicide, proactively preventing SH can be an effective way to reduce suicidal risk among teenagers.

Identifying the influencing factors of SH is crucial for SH prevention. In recent years, the positive link between poor mental health and SH has been repeatedly reported in adolescent populations: Impulsivity, anger dysregulation, and low self-esteem are the identified risk factors for SH in adolescents[5,6]. Personality traits are also significantly associated with adolescent SH. A study on Norwegian adolescents found that neuroticism was a risk factor that contributed to SH in youth[7]. Similarly, among Italian middle school students, those with more impulsive and aggressive personalities were more likely to report SH[8]. A domestic study in Chinese college students suggested that, those with higher extraversion scores (E scores) in the Eysenck personality questionnaire were at higher risk of SH[9]. In addition, a cross-sectional study with a large sample size showed that susceptible personality traits were significantly related to SH consciousness[10].

As a long-lasting and stable feature of an individual, personality is hard to intervene directly. Therefore, exploring modifiable factors which lie along the pathway between personality and SH would be more practicable in preventing personality-associated SH among adolescents. In recent years, some studies have found that mental resilience plays a beneficial role in protecting adolescents from SH[11-13]. Psychological resilience refers to the ability of an individual to adjust to changes when experiencing a traumatic, or negative, or frustrating event[14]. Many studies have shown that personality traits are significantly associated with resilience: For instance, extroversion, conscientiousness, and openness have been shown to be positively correlated with resilience, whereas emotionality has shown a negative association[15,16]. All of these findings suggest that resilience may play a mediating role in the association between personality traits and SH; however, this hypothesis has never been thoroughly investigated.

Aiming to address this shortcoming, the current study used a large representative sample of Chinese children and adolescents to examine the relationship between personality traits and SH, and more importantly, the possible mediation effect of resilience on personality-associated SH.

The data used for analysis in this study were obtained from the Mental Health Survey of Children and Adolescents in Kaiyuan. A cross-sectional survey was carried out in Kaiyuan, Yunnan province in southwest China, from October 27 to November 4, 2020. The survey used a population-based two-stage simple random cluster sampling method with probability proportionate to sample size (PPS) design. It was carried out in two stages: In stage one, eight primary schools, nine junior high schools and two senior high schools were randomly selected from all schools in Kaiyuan; in stage two, 3–4 classes were randomly selected from each chosen school, and all students within the chosen classes who met the inclusion criteria were included.

Based on the literature, we set a conservative SH prevalence of 20%, and an acceptable error rate of 2% was determined. According to the simple random sampling sample size calculation method, we reached a preliminary required sample size of 1600. Considering that the sampling error in the cluster samples would inevitably be higher than that in random samples, we used a design effect of ‘2’ to further adjust for the required sample size, and the final calculated sample size was 3200.

In this study, except for personality, SH, and resilience, we also measured suicide ideation among the respondents. Since children under the age of 10 cannot fully understand the definition and consequences of suicide[17], we only included adolescents aged 10 years old and above. Subjects were further excluded if at least one of the following exclusion criteria was satisfied: (1) Unable to complete the questionnaire due to severe psychological or physical illnesses; (2) Having a speech disorder, communication disorder or reading comprehension disorder; and (3) Refused to participate. Before the survey, the written informed consent of the respondents was obtained from their legal guardians. In addition, when the survey was underway, verbal consent was also obtained from the respondents themselves.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Board of Kunming Medical University, No. KMMU2020MEC047.

A structured questionnaire was used to collect information from the participants. This questionnaire mainly measures demographics, personality traits, anxiety and depression, SH behaviors, psychological resilience, suicide ideation, and parenting styles. The demographics section consisted of factual questions, and validated instruments were used for all of the other sections. In the current study, we used the following sections to perform the data analysis: General characteristics, SH behavior, psychological resilience, personality traits, depression, and anxiety.

SH behaviors: The modified version of the Adolescents Self-Harm Scale (MASHS) developed by Feng[18] was used to measure lifetime SH behaviors[18]. The MASHS includes 18 items measuring frequency (never, 1 time; 2–4 times, 5 times and above) and severity (non-observable, mild, moderate, severe, devastating) of the 18 most common SH behaviors in Chinese adolescents.

Personality traits: The children’s version of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire developed by Eysenck and other researchers in 1975 was used to assess personality traits[19]. The questionnaire consists of 88 items, divided into four subscales: Neuroticism (N); psychoticism (P); E; lie (L). The first three scales represent the three dimensions of the personality structure and are independent of each other. The L scale is a measure of effectiveness and represents the personality traits related to false trust. Each question is scored ‘1’ or ‘0’, and finally converted into a normal standard T score. For the L scale, a T score greater than 61.5 was taken to indicate a lack of authenticity. The T scores for N, P, and E scales were collectively used to classify subjects into five levels. E (extraversion) was divided into: Typical introversion (T ≤ 38.5), introversion (38.5 < T ≤ 43.3), extraversion intermediate (43.3 < T ≤ 56.7), extroversion (56.7 < T ≤ 61.5), and typical extroversion (T > 61.5). N was divided into: Typical non-neuroticism (T ≤ 38.5), non-neuroticism (38.5 < T ≤ 43.3), neuroticism intermediate (43.3 < T ≤ 56.7), neuroticism (56.7 < T ≤ 61.5), and typical neuroticism (T > 61.5). P was divided into: Typical non-psychoticism (T ≤ 38.5), non-psychoticism (38.5 < T ≤ 43.3), psychoticism intermediate (43.3 < T ≤ 56.7), psychoticism (56.7 < T ≤ 61.5), and typical psychoticism (T > 61.5)[9,20]. The Cronbach’s α was 0.891 (Bootstrap 95%CI: 0.886-0.896).

Depression and anxiety: The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) were used to assess the subjects’ experience of depression and anxiety in the past two weeks. There are nine items on the PHQ-9, which correspond to the nine diagnostic criteria for depression (interest in doing things, mood fluctuations, sleep quality, vitality, appetite, self-evaluation, concentration on things, speed of movement, thoughts of suicide)[21]. The GAD-7 contains seven items, which measure nervousness, anxiety, uncontrollable worry, excessive worry, inability to relax, inability to sit still, irritability, and ominous premonition[22]. Each item on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 is divided into four levels by severity of the scenario: Not at all (0 point), several days (1 point), more than half of the days (2 points), almost every day (3 points). A higher combined score was taken to indicate more severe symptoms of depression or anxiety[23]. The Cronbach’s α for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were 0.883 (Bootstrap 95%CI: 0.874-0.890) and 0.909 (Bootstrap 95%CI: 0.902-0.915).

Resilience: The Resilience Scale for Chinese Adolescents (RSCA) compiled by Hu and Gan[24] was used. It contains 27 items, including two dimensions of personal strength and support. The personal strength dimension is divided into three factors: Goal concentration, emotion regulation, and positive perception. The support dimension is divided into two factors: Family support and interpersonal assistance. The questionnaire is scored using a five-point scale (1-totally disagree, 2-disagree, 3-not sure, 4-agree, 5-totally agree), with a higher total score representing a higher level of mental resilience[24]. The Cronbach’s α was 0.846 (Bootstrap 95%CI: 0.837-0.855).

We used the R software (Version 4.0.3, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) to perform the statistical analysis, and the “Survey” package has been mainly used to adjust for unequal sampling probability. Descriptive statistics are presented to describe the general characteristics of the survey subjects, t tests, chi-squared tests, and rank-based non-parametric tests were carried out to compare the differences between subgroups as appropriate to variable type. Univariate and multivariate binary unconditional logistic regression models were used to explore the crude and adjusted associations between personality traits and SH (prevalence, repetition, severity). A series of path models were fitted to examine psychological resilience as a mediator of the associations between personality and SH prevalence, SH severity, and SH repetition. Except for the univariate logistic regression models which adopted a lower significance level of 0.10 to screen for possible covariates, the significance level for all of the other statistical analyses was set as 0.05 (two-tailed).

A total of 4780 children and adolescents met the inclusion criteria, of whom 57 were excluded because of incomplete information. A further 252 respondents were defined as untrustworthy because their EPQ-L scores were greater than 61.5. In the end, 4471 subjects were included in the analysis, and the effective response rate was 93.5%. Among all analyzed participants, 1795 reported SH behaviors, accounting for 40.1% (95%CI: 34.4%-46.0%). In respect to the general characteristics listed in Table 1, except for sex and ethnicity, statistically significant differences were found between respondents who self-harmed and those who did not SH. The T sores for the E, N, and P dimensions of personality traits were also different between the two groups. Compared with SH subjects, subjects who did not SH reported a consistently higher level of resilience, either in general, or on the five specific dimensions.

| Features | Total (n = 4471) | SH (n = 1795) | Non-SH (n = 2676) | Test statistic | P value |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (X bar ± S) | 13.01 (0.40) | 13.42 (0.34) | 12.73 (0.43) | -11.991 | 0.01 |

| Sex, n, (%): Boys | 2184 (48.8) | 824 (45.9) | 1360 (50.8) | 3.172 | 0.09 |

| Ethnicity, n, (%) | 0.372 | 0.67 | |||

| Han | 1242 (27.8) | 504 (28.1) | 738 (27.6) | ||

| Yi | 1788 (40.0) | 693 (38.6) | 1095 (40.9) | ||

| Others | 1441 (32.2) | 598 (33.3) | 843 (31.5) | ||

| Grade, n, (%) | 32.242 | 0.01 | |||

| Primary school | 1472 (32.9) | 374 (20.8) | 1098 (41.0) | ||

| Junior high school | 2442 (54.6) | 1157 (64.5) | 1285 (48.0) | ||

| Senior high school | 557 (12.5) | 264 (14.7) | 293 (10.9) | ||

| Mental health | |||||

| Depression, n, (%): Yes (PHQ9 ≥ 10) | 501 (11.2) | 411 (22.9) | 90 (3.4) | 176.272 | 0.01 |

| Anxiety, n, (%): Yes (GAD7 ≥ 7) | 778 (17.4) | 570 (31.8) | 208 (7.8) | 244.432 | 0.01 |

| Personality traits | |||||

| EPQ-E, n, (%) | 3.543 | 0.01 | |||

| Typical extroversion: Score E > 61.5 | 1024 (22.9) | 357 (19.9) | 667 (24.9) | ||

| Extroversion: 56.7 < score E ≤ 61.5 | 740 (16.6) | 270 (15.0) | 470 (17.6) | ||

| Intermediate: 43.3 < score E ≤ 56.7 | 1825 (40.8) | 763 (42.5) | 1062 (39.7) | ||

| Introversion: 38.5 < score E ≤ 43.3 | 419 (9.4) | 191 (10.6) | 228 (8.5) | ||

| Typical introversion: score E ≤ 38.5 | 463 (10.4) | 214 (11.9) | 249 (9.3) | ||

| EPQ-N, n, (%) | -18.103 | 0.01 | |||

| Typical neuroticism: Score N > 61.5 | 646 (14.4) | 510 (28.4) | 136 (5.1) | ||

| Neuroticism: 56.7 < score N ≤ 61.5 | 323 (7.2) | 197 (11.0) | 126 (4.7) | ||

| Intermediate: 43.3 < score N ≤ 56.7 | 1227 (27.4) | 574 (32.0) | 653 (24.4) | ||

| Non-neuroticism: 38.5 < score N ≤ 43.3 N ≤ 43.3 | 552 (12.3) | 189 (10.5) | 363 (13.6) | ||

| Typical non-neuroticism: Score N ≤ 38.5 NN ≤ 38.5 | 1723 (38.5) | 325 (18.1) | 1398 (52.2) | ||

| EPQ-P, n, (%) | -11.023 | 0.01 | |||

| Typical psychoticism: score P > 61.5 | 422 (9.4) | 289 (16.1) | 133 (5.0) | ||

| Psychoticism: 56.7 < score P ≤ 61.5 | 518 (11.6) | 308 (17.2) | 210 (7.8) | ||

| Intermediate: 43.3 < score P ≤ 56.7 | 2335 (52.2) | 967 (53.9) | 1368 (51.1) | ||

| Non-psychoticism: 38.5 < score P ≤ 43.3 | 1026 (22.9) | 211 (11.8) | 815 (30.5) | ||

| Typical non-psychoticism: Score P ≤ 38.5 | 170 (3.8) | 20 (1.1) | 150 (5.6) | ||

| Resilience (Median, IQR) | |||||

| Combined score | 89 (19) | 84 (16) | 93 (20) | -15.983 | 0.01 |

| Goal concentration | 17 (6) | 16 (6) | 18 (6) | -11.173 | 0.01 |

| Emotion regulation | 20 (7) | 18 (7) | 21 (6) | -13.263 | 0.01 |

| Positive perception | 14 (5) | 13 (5) | 14 (5) | -2.683 | 0.02 |

| Family support | 21 (6) | 19 (5) | 22 (5) | -10.273 | 0.01 |

| Interpersonal assistance | 20 (6) | 18 (6) | 21 (6) | -10.933 | 0.01 |

Based on univariate logistic regression analysis, age, gender, grade, anxiety, depression, resilience, and all of the personality trait dimensions (extraversion, neuroticism, psychoticism) were included into the subsequent multivariate logistic regression models: Model 1 represented the adjusted associations between the three dimensions of personality traits and SH; Model 2 revealed the adjusted association between resilience and SH; in Model 3, personality traits and resilience were simultaneously incorporated into the model, and the results indicated that typical introverted personality types (E ≤ 38.5) were associated with an increased risk of SH (OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 1.14-1.87), whereas a more stable mood (a lower N score) (OR = 0.19, 95%CI: 0.13-0.26) and a lower psychotic score (P ≤ 56.7) (OR = 0.29, 95%CI: 0.17-0.51) were associated with a decreased risk of SH (Table 2).

| Variable | Univariate model; Crude OR (90%CI) | Multivariate model 1; Adjusted OR (95%CI) | Multivariate model 2; Adjusted OR (95%CI) | Multivariate model 3; Adjusted OR (95%CI) |

| Age: +1 yr | 1.20 (1.14-1.27) | 1.00 (0.93-1.08) | 1.03 (0.95-1.11) | 1.01 (0.94-1.09) |

| Sex (Ref: Boys): Girls | 1.22 (1.01-1.46) | 0.98 (0.75-1.28) | 1.09 (0.89-1.34) | 0.98 (0.76-1.27) |

| Grade (Ref: Primary school) | ||||

| Junior high school | 2.64 (2.11-3.31) | 1.81 (1.23-2.67) | 2.18 (1.49-3.19) | 1.82 (1.24-2.69) |

| Senior high school | 2.65 (2.01-3.48) | 1.43 (0.89-2.30) | 2.12 (1.29-3.49) | 1.51 (0.93-2.46) |

| Depression (Ref: PHQ9 < 10): PHQ9 ≥ 10 | 8.53 (6.29-11.59) | 2.21 (1.49-3.27) | 3.30 (2.56-4.82) | 2.18 (1.47-3.23) |

| Anxiety (Ref: GAD7 < 7): GAD7 ≥ 7 | 5.52 (4.55-6.69) | 1.43 (1.14-1.78) | 2.28 (1.84-2.83) | 1.37 (1.10-1.70) |

| Personality traits | ||||

| EPQ-E (Ref: Typical extroversion, score E > 61.5) | ||||

| Extroversion (56.7 < score E ≤ 61.5) | 1.07 (0.94-1.22) | 1.10 (0.90-1.34) | 1.05 (0.85-1.29) | |

| Intermediate (43.3 < score E ≤ 56.7) | 1.34 (1.16-1.55) | 1.29 (1.06-1.57) | 1.13 (0.92-1.40) | |

| Introversion (38.5 < score E ≤ 43.3) | 1.57 (1.26-1.95) | 1.50 (1.17-1.91) | 1.21 (0.94-1.54) | |

| Typical introversion (score E ≤ 38.5) | 1.61 (1.26-2.04) | 1.90 (1.41-2.56) | 1.46 (1.14-1.87) | |

| EPQ-N (Ref: Typical neuroticism, score N > 61.5) | ||||

| Neuroticism (56.7 < score N ≤ 61.5) | 0.42 (0.33-0.52) | 0.63 (0.45-0.88) | 0.64 (0.45-0.91) | |

| Intermediate (43.3 < score N ≤ 56.7) | 0.23 (0.20-0.27) | 0.45 (0.34-0.60) | 0.50 (0.37-0.67) | |

| Non-neuroticism (38.5 < score N ≤ 43.3) | 0.14 (0.11-0.18) | 0.31 (0.21-0.46) | 0.36 (0.24-0.54) | |

| Typical non-neuroticism (score N ≤ 38.5) | 0.06 (0.05-0.08) | 0.16 (0.11-0.22) | 0.19 (0.13-0.26) | |

| EPQ-P (Ref: Typical psychoticism, score P > 61.5) | ||||

| Psychoticism (56.7 < score P ≤ 61.5) | 0.67 (0.51-0.90) | 0.83 (0.61-1.13) | 0.86 (0.62-1.19) | |

| Intermediate (43.3 < score P ≤ 56.7) | 0.33 (0.24-0.44) | 0.66 (0.47-0.93) | 0.73 (0.51-1.03) | |

| Non-psychoticism (38.5 < score P ≤ 43.3) | 0.12 (0.09-0.17) | 0.36 (0.26-0.50) | 0.42 (0.30-0.58) | |

| Typical non-psychoticism (score P ≤ 38.5) | 0.06 (0.04-0.09) | 0.25 (0.14-0.42) | 0.29 (0.17-0.51) | |

| Resilience (Ref: RSCA < 89): RSCA ≥ 89 | 0.32 (0.27-0.36) | 0.42 (0.36-0.50) | 0.63 (0.52-0.77) |

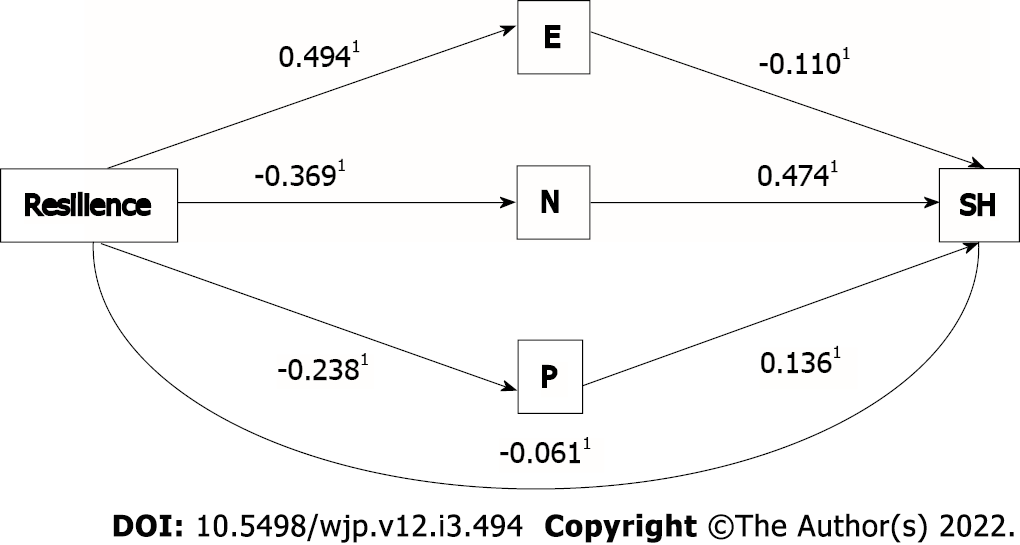

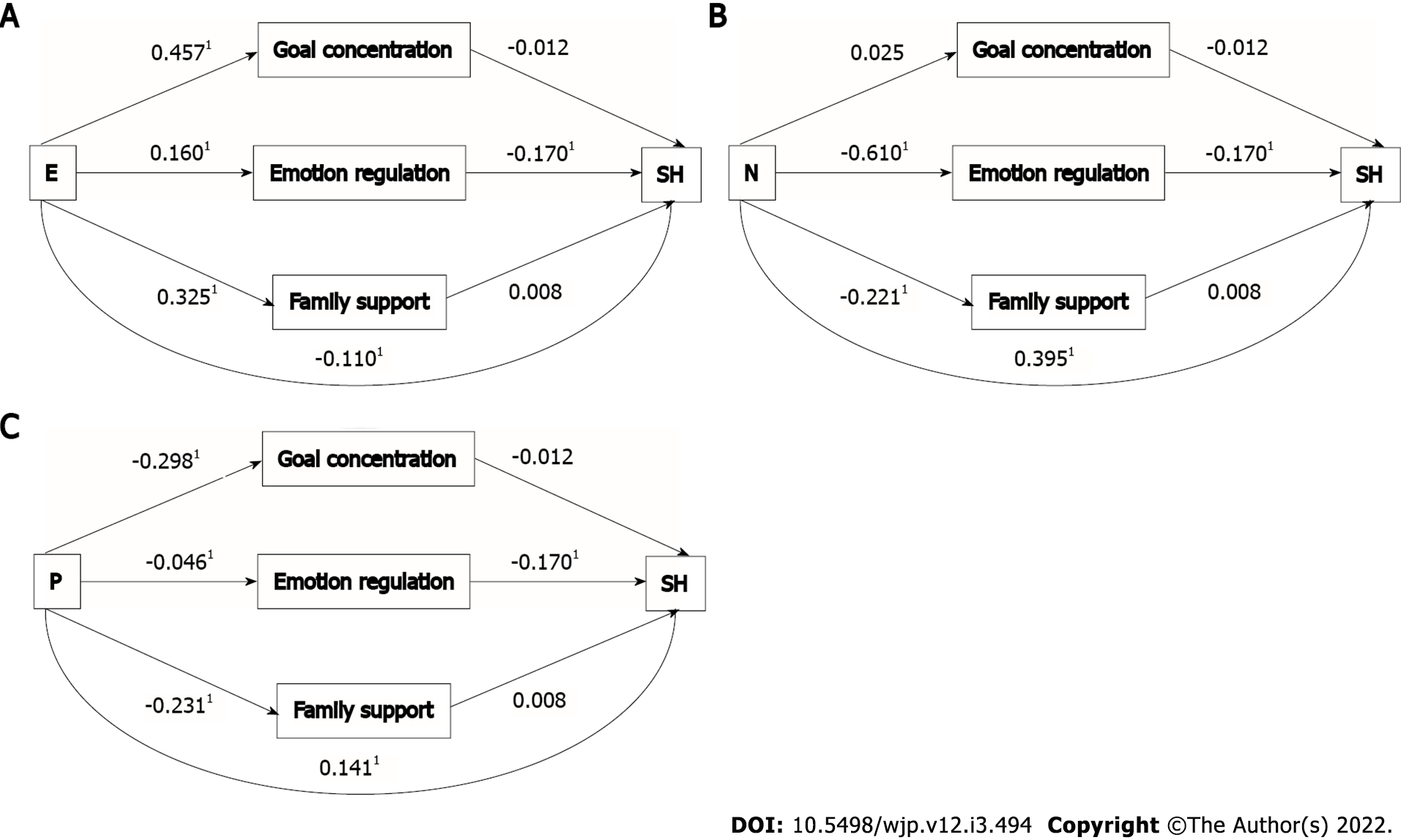

Based on the results of the multivariate logistic regression models, we constructed a possible path model to illustrate resilience as a mediator of the associations between the three personality trait dimensions and SH prevalence. The analytical results showed that the mediation effect of resilience for all of the three personality trait dimensions was significant: The standardized path coefficients were -0.0301 (0.494 × -0.061), 0.0225 (-0.369 × -0.061), and 0.0145 (-0.238 × -0.061), which accounted for 21.5%, 4.53%, and 9.65% of the total associations, respectively (Figure 1). We further dissected this association based on the five dimensions of resilience. The path model suggested that among the three significant dimensions of resilience identified by a prior multivariate logistic regression model (the results are summarized in Supplementary Table 1), only emotion regulation was identified as a prominent mediator (Figure 2).

We intended to further analyze the possible mediation effect of emotion regulation in terms of the associations between personality traits and SH repetition, as well as SH severity. However, the preliminary multivariate analysis revealed that the adjusted associations between emotion regulation and SH repetition/severity were all insignificant (Supplementary Table 2); thus, the suspected mediation effect was not found.

In the current study, we discussed the relationship between personality traits and SH in a large representative sample of Chinese children and adolescents. The analysis of the results showed that all personality trait dimensions were significantly related to the prevalence of SH after adjusting for other covariates. Resilience played a noticeable mediating role in terms of the associations between different dimensions of personality (E, N, P) and SH, accounting for 21.5%, 4.53%, and 9.65% of the total associations, respectively. Further analysis revealed that, for different dimensions of resilience, only emotion regulation was identified as a prominent mediator in this association. The current study could provide valuable evidence for personality-associated SH prevention in children and adolescents.

A high lifetime prevalence of SH (40.1%) was found in our study sample, and this prevalence was much higher than that previously reported. For example, two previously published meta-analysis papers found a lifetime SH prevalence of 13.7% (95%CI: 11.0%-17.0%) and 16.9% (95%CI: 15.1%-18.9%) among children and adolescents globally[2,25]. Another meta-analysis found that the prevalence of SH among Chinese adolescents was 22.37%[3], which is comparable to our previous study involving children and adolescents who were randomly chosen from another city (Lincang) of Yunnan province, with a reported lifetime prevalence of SH of 47%[12]. These prominent differences in the lifetime prevalence of SH can likely be attributed to heterogeneity in SH instruments and definitions, which prevent a direct comparison of the studies involving different children and adolescent populations.

An important finding of our study is that personality traits were significantly associated with SH prevalence: Higher E scores were correlated with lower SH odds, whereas higher N and P scores were associated with an increased risk of SH. These associations were well supported by existing literature. First of all, introverts may find it more difficult to integrate into society, although no pertinent studies have been published to elaborate upon the influence of introversion on SH, and a higher risk of future suicide has been reported among introverted college students[26]. The positive association that was identified in the current study between neuroticism and SH is in line with the results published by Hafferty et al[27]. Another meta-analysis on neuroticism and suicide ideation showed that neuroticism was also a significant risk factor for suicide ideation and is of great significance for suicide prevention[28]. The positive connection between psychoticism and SH can also be justified. Studies have found that high psychoticism individuals exhibited higher levels of impulsivity and aggressiveness, which are known risk factors for SH[29,30].

The path analysis results indicated that resilience was a significant mediator of the association between all personality trait dimensions and SH. In general, resilience is related to positive personality traits such as optimism, persistence, cooperation, maturity, and responsibility[31]. A study on American college students also found that neuroticism in personality traits was negatively correlated with resilience, while conscientiousness and extroversion were positively correlated with resilience[16,32]. In addition, existing studies have shown that resilience has a protective effect on the occurrence of SH in adolescents, and adolescents with higher levels of resilience were less likely to develop SH[11]. In the relationship between personality and SH, resilience-mediated associations accounted for over one-fifth (21.5%) of the total association for the extraversion dimension, which was the highest among all of the three dimensions. This finding probably suggests that, for introverted children and adolescents, building up resilience might be an effective way to prevent personality-related SH.

Resilience is a composite definition. Our further analysis revealed that, among the five dimensions of resilience, only emotion regulation was a significant mediator of the association between personality traits and SH. Emotion regulation refers to the ability to respond to the ongoing demands of experience with a range of emotions in a socially tolerable manner[33]. A newly published study found that poor emotion regulation was an important cause of SH[34]. In addition, a retrospective study has also indicated that there were differences in the ability to control emotions among individuals with different personalities[35]. Therefore, among all dimensions of resilience, improving emotion regulation ability could be regarded as the priority in antagonizing personality-associated SH among children and adolescents. Currently, some effective intervention methods in improving emotion regulation ability have already been proposed. Since SH has a high prevalence in children and adolescents, group-based therapy should be prioritized when considering interventions. Acceptance-based emotion regulation group therapy had a good effect on improving emotion regulation ability and reducing SH: It focuses on controlling behavior when emotions are present, rather than controlling emotions themselves[36-38]. Domestic studies have also shown that acceptance-commitment therapy has a positive effect on the acceptance of bad emotions and feelings, as well as on the rational use of emotion regulation strategies in patients with bipolar disorder[39]. Moreover, although studies on emotion regulation intervention strategies were also published recently in China, they mainly focused on clinical populations, such as depressed teenagers[40]. Therefore, the usefulness and effectiveness of available emotion regulation intervention methods for the general child and adolescent population in China are yet to be corroborated.

The major advantages of the current research are that it involved a large population-based representative sample of Chinese children and adolescents, and the study design and implementation were scientific and rigorous. However, two limitations should be noted. First, due to the cross-sectional design, causal inferences were impossible. Second, the entire study sample was chosen from a single province in southwest China; therefore, the results cannot be generalized to the entire Chinese child and adolescent population.

In this cross-sectional study, we discussed the relationship between personality traits and SH in a large sample of Chinese children and adolescents. More importantly, we thoroughly examined the mediating role of resilience in this relationship. We found that personality traits were significantly associated with SH, and resilience was identified as a prominent mediator. Further analysis revealed that, for all the dimensions of resilience, emotion regulation was the only noticeable mediator. The major findings of our study are of significance in preventing seemingly unchangeable personality-associated SH among children and adolescents: For introverted individuals, interventions that focus on reinforcing resilience might be a promising strategy. This hypothesis should be further corroborated by future intervention studies.

Children and adolescents are at increased risk of self-harm (SH), an established indicator of future suicide. Published studies support a positive relationship between personality traits and SH. There is a possibility that resilience may play a mediating role in the association between personality traits and SH; however, this hypothesis has never been thoroughly investigated.

The current study aimed to provide valuable evidence for identifying personality traits that are associated with SH in children and adolescents.

To investigate resilience as a mediator of the association between personality traits and SH among a large representative sample of Chinese children and adolescents.

We surveyed 4780 children and adolescents from Kaiyuan City, Honghe Prefecture, Yunnan province, China. The children’s version of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire was used to assess the personality traits. The Chinese Youth psychological resilience scale was used to measure the level of resilience. The revised version of the Adolescent Self-harm Scale was used to measure the lifetime prevalence of SH among the survey subjects. We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression models and path analysis to evaluate resilience as a mediator.

Among the 4471 subjects included into the final analysis, the prevalence of SH was 40.1% (95%CI: 34.4%-46.0%). For different dimensions of personality traits, higher E-dimension scores and lower N- and P-dimension scores were associated with a lower SH prevalence. Resilience was identified as an obvious mediator of the associations between the three dimensions of personality and SH, accounting for 21.5%, 4.53%, and 9.65%, respectively, of the total associations. In addition, we found that, among the five dimensions of resilience, only emotion regulation was identified as a significant mediator.

According to the current research results, we found that resilience was a significant mediator of the association between personality traits and SH, especially the dimension of emotion regulation. Intervention measures which aim to improve resilience may be effective in preventing personality traits that are associated with SH in Chinese children and adolescents.

Future interventional studies are warranted to further corroborate our major findings.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cotez CM, Hosak L, Vyshka G S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

| 1. | Hawton K, Hall S, Simkin S, Bale L, Bond A, Codd S, Stewart A. Deliberate self-harm in adolescents: a study of characteristics and trends in Oxford, 1990-2000. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:1191-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lim KS, Wong CH, McIntyre RS, Wang J, Zhang Z, Tran BX, Tan W, Ho CS, Ho RC. Global Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of Suicidal Behavior, Deliberate Self-Harm and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Children and Adolescents between 1989 and 2018: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 51.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lang J, Yao Y. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in chinese middle school and high school students: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Eckenrode J, Purington A, Baral Abrams G, Barreira P, Kress V. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:486-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lockwood J, Daley D, Townsend E, Sayal K. Impulsivity and self-harm in adolescence: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26:387-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chang SH, Hall WA, Campbell S, Lee L. Experiences of Chinese immigrant women following "Zuo Yue Zi" in British Columbia. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:e1385-e1394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Junker A, Nordahl HM, Bjørngaard JH, Bjerkeset O. Adolescent personality traits, low self-esteem and self-harm hospitalisation: a 15-year follow-up of the Norwegian Young-HUNT1 cohort. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28:329-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Di Pierro R, Sarno I, Perego S, Gallucci M, Madeddu F. Adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: the effects of personality traits, family relationships and maltreatment on the presence and severity of behaviours. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21:511-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen F, Huang J, Zhang LS. Influencing factors of self-injury behavior among undergraduates by two-level binary Logistic regression model. Chinese J Dis Cont Preven. 2017;21:387-390. |

| 10. | Kuang L, Wang W, Huang Y, Chen X, Lv Z, Cao J, Ai M, Chen J. Relationship between Internet addiction, susceptible personality traits, and suicidal and self-harm ideation in Chinese adolescent students. J Behav Addict. 2020;9:676-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Xiao Y, He L, Chen Y, Wang Y, Chang W, Yu Z. Depression and deliberate self-harm among Chinese left-behind adolescents: A dual role of resilience. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;48:101883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ran H, Cai L, He X, Jiang L, Wang T, Yang R, Xu X, Lu J, Xiao Y. Resilience mediates the association between school bullying victimization and self-harm in Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tian X, Chang W, Meng Q, Chen Y, Yu Z, He L, Xiao Y. Resilience and self-harm among left-behind children in Yunnan, China: a community-based survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xu MJ, Wan PY, Yang XG. Positive cognitive emotion regulation and psychological resilience on suicide ideation among left-behind adolescents. Modern Preven Med. 2016;43:4143-4146. |

| 15. | Nakaya M, Oshio A, Kaneko H. Correlations for Adolescent Resilience Scale with big five personality traits. Psychol Rep. 2006;98:927-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Campbell-Sills L, Cohan SL, Stein MB. Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:585-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 652] [Cited by in RCA: 572] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mishara BL. Conceptions of death and suicide in children ages 6-12 and their implications for suicide prevention. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1999;29:105-118. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Feng Y. The relationship of adolecents'self-harm behaviors, individual emotion characteristics and family environment factors. Cent China Normal Uni. 2008;. |

| 20. | Zhang Y. Investigation on Depressive State of Cadet Pilots and Analysis of Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Pract Pre Med. 2009;16:378-379. |

| 21. | Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365:l1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1320] [Cited by in RCA: 1108] [Article Influence: 123.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737-1744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6086] [Cited by in RCA: 6845] [Article Influence: 263.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hu YQ, Gan YQ. Development and Psychometric Validity of the Resilience Scale for Chinese Adolescents: Development and Psychometric Validity of the Resilience Scale for Chinese Adolescents. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2008;8:902-912. |

| 25. | Gillies D, Christou MA, Dixon AC, Featherston OJ, Rapti I, Garcia-Anguita A, Villasis-Keever M, Reebye P, Christou E, Al Kabir N, Christou PA. Prevalence and Characteristics of Self-Harm in Adolescents: Meta-Analyses of Community-Based Studies 1990-2015. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57:733-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mars B, Heron J, Klonsky ED, Moran P, O'Connor RC, Tilling K, Wilkinson P, Gunnell D. Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:327-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hafferty JD, Navrady LB, Adams MJ, Howard DM, Campbell AI, Whalley HC, Lawrie SM, Nicodemus KK, Porteous DJ, Deary IJ, McIntosh AM. The role of neuroticism in self-harm and suicidal ideation: results from two UK population-based cohorts. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54:1505-1518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Garcia HA, Sanchez-Meca J, Alvarez MF, Rubio-Aparicio M, Navarro-Mateu F. [Neuroticism and suicidal thoughts: a meta-analytic study]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2018;92:e201808049. |

| 29. | Lockwood J, Townsend E, Daley D, Sayal K. Impulsivity as a predictor of self-harm onset and maintenance in young adolescents: a longitudinal prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:583-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | O'Donnell O, House A, Waterman M. The co-occurrence of aggression and self-harm: systematic literature review. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:325-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Eley DS, Cloninger CR, Walters L, Laurence C, Synnott R, Wilkinson D. The relationship between resilience and personality traits in doctors: implications for enhancing well being. PeerJ. 2013;1:e216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Shi M, Liu L, Wang ZY, Wang L. The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between big five personality and anxiety among Chinese medical students: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: a clinical perspective. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59:73-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Brereton A, McGlinchey E. Self-harm, Emotion Regulation, and Experiential Avoidance: A Systematic Review. Arch Suicide Res. 2020;24:1-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hughes DJ, Kratsiotis IK, Niven K, Holman D. Personality traits and emotion regulation: A targeted review and recommendations. Emotion. 2020;20:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gratz KL, Gunderson JG. Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behav Ther. 2006;37:25-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Gratz KL, Tull MT. Extending research on the utility of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality pathology. Personal Disord. 2011;2:316-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gratz KL, Weiss NH, Tull MT. Examining Emotion Regulation as an Outcome, Mechanism, or Target of Psychological Treatments. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;3:85-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Li M, Shi JY, Feng G, Shi YQ, Sun LL, Li L, Wang BH. The Intervention of Group Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Emotion Regulation of Patients with Bipolar Disorder (BD). World Latest Med Infor. 2019;19:23-24+27. |