Published online Nov 19, 2022. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v12.i11.1313

Peer-review started: January 16, 2022

First decision: April 18, 2022

Revised: April 28, 2022

Accepted: August 12, 2022

Article in press: August 12, 2022

Published online: November 19, 2022

Processing time: 304 Days and 23.6 Hours

To summarize the most relevant data from a systematic review on the impact of COVID-19 on children and adolescents, particularly analyzing its psychiatric effects.

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and included experimental studies (randomized-individually or pooled-and non-randomized controlled trials), observational studies with a group for internal comparison (cohort studies-prospective and retrospective-and case-control) and qualitative studies in the period from 2021 to 2022.

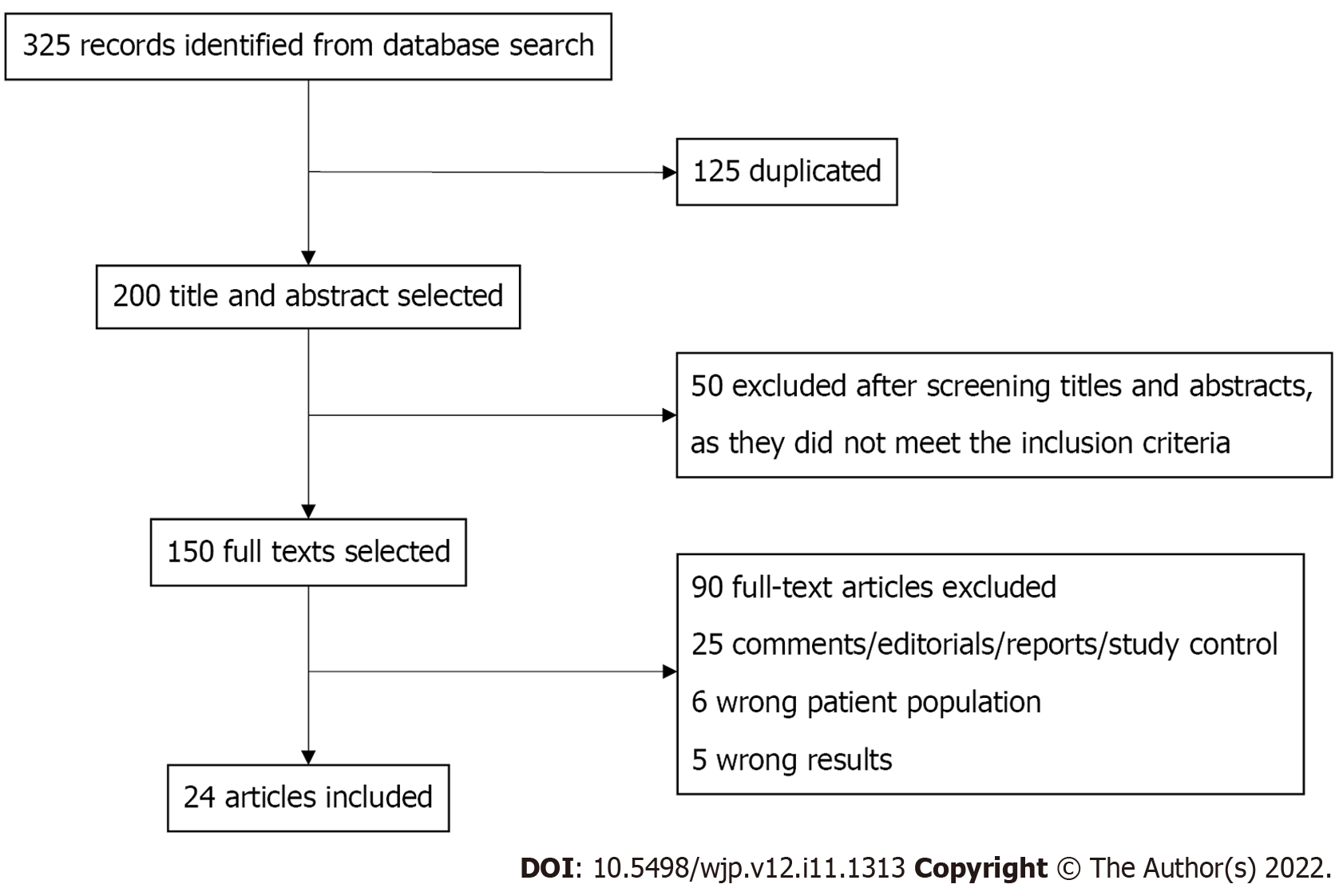

The search identified 325 articles; we removed 125 duplicates. We selected 200 manuscripts, chosen by title and selected abstracts. We excluded 50 records after screening titles and abstracts, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. We retrieved 150 records selected for a full reading. We excluded 90 text articles and we selected 25 records for the (n) final. Limitations: Due to the short period of data collection, from 2021 to 2022, there is a possibility of lack of relevant studies related to the mental health care of children and adolescents. In addition, there is the possibility of publication bias, such as only significant findings being published.

The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of children and adolescents is of great concern to child and youth psychiatry. Situations such as fear, anxiety, panic, depression, sleep and appetite disorders, as well as impairment in social interactions caused by psychic stress, are punctual markers of pain and psychic suffering, which have increasing impacts on the mental health panorama of children and adolescents globally, particularly in vulnerable and socially at-risk populations.

Core Tip: Fear, anxiety, panic, depression, sleep, and appetite disorders, as well as impairment in social interactions caused by psychic stress are punctual markers of pain and psychic suffering, which have increasing impacts on the mental health panorama of children and adolescents in the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

- Citation: Gabriel IWM, Lima DGS, Pires JP, Vieira NB, Brasil AAGM, Pereira YTG, Oliveira EG, Menezes HL, Lima NNR, Reis AOA, Alves RNP, Silva UPD, Gonçalves Junior J, Rolim-Neto ML. Impacts of COVID-19 on children and adolescents: A systematic review analyzing its psychiatric effects. World J Psychiatry 2022; 12(11): 1313-1322

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v12/i11/1313.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i11.1313

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused pain and psychological suffering in children and adolescents, particularly considering the new variants of the disease[1]. Psychologically stressful situations are the main effects caused to populations under the influence of COVID-19, which can contribute to the development of post-traumatic stress symptoms, especially for vulnerable children/adolescents (C-A) in critical developmental stages, with variable prevalence, risk factors, and severity[2]. Recent studies highlight that C-A are more likely to have high rates of depressive or anxiety disorders, impairing family, school, cultural, and social interactions, with multiple and adverse consequences to mental health in the medium and long term[3,4].

Current studies have observed that parental stress, co-parenting, emotional well-being, and children and adolescents’ adjustment were impacts that acted unfavorably in the COVID-19 pandemic[5,6]. These findings highlight the psychic burden and stress faced by caregivers of C-A with disabilities and compromised psychiatric development during the pandemic.

In this context, C-A with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) have higher levels of distress compared to typically developing children. Distress levels may be heightened by restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic[7,8]. Parents’ perceptions of how the pandemic has mitigated their mental health have implications for their well-being and that of their children, with a stronger association for low-income families[9].

Although parenting is essential for positive development, increased parental distress interferes with children’s well-being. Sesso et al[10] warn that internalization problems in C-A with NDD were among the strongest predictors of parental stress during the pandemic lockdown. The dysfunctional interactions of a child are usually mediated by their internalizing/externalizing problems[11,12]. In this context, parents of children with NDD should be valued groups in public policies to promote mental health in the post-pandemic period[13].

It is also important to highlight that the prevalence of anxiety generally varies from 19% to 64% and depression from 22.3% to 43.7% among adolescents. Among children aged 5 to 12 years, the prevalence of anxiety ranges from 19% to 78%, while depression among adolescents ranges from 6.3% to 22.6%[14]. Among preschool-age children, some studies have found that behavioral and emotional problems worsen during the pandemic[4,15].

This paper aims to summarize the most relevant data on the impact of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic on C-A through a systematic review, particularly analyzing its psychiatric effects.

A systematic review was carried out using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) protocol from 2021 to 2022. Qualitative studies, quantitative studies (e.g., prospective/retrospective cohorts, case-control studies), and experimental studies (randomized, pooled or individual, and non-randomized controlled trials) were included. Case reports, case studies, opinions, editorials, letters, and conference abstracts were excluded.

The following descriptors were used with the respective Boolean operators: “2019 nCoV” OR # 2019 nCoV OR “2019 novel coronavirus” OR “COVID 19” OR “COVID19” OR “new coronavirus” OR “novel coronavirus” OR “SARS CoV-2” OR “Mental health” OR “depression” OR “Anxiety” OR “Child Psychiatry” OR “Adolescent Psychiatry”.

We searched the Web of Science Index Medicus, MEDLINE, WHO COVID-19 databases, EMBASE, Scopus, and Cochrane Library. Non-indexed databases, including MedRxiv preprint and Google Scholar, were also used. To identify missing documents, all systematic reviews and relevant comments were manually searched.

Studies on children and adolescents aged 3 to 19 years from 2021 to 2022, and which focused on psychiatric interventions in children and adolescents during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic were included.

Articles were included only if the study exclusively examined the mental health impacts of COVID-19 on children and adolescents from 2021 to 2022. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. Using Covidence, a web-based tool that helps to identify studies and involves data extraction processes, two reviewers (MLRN and JPP) independently examined all potential articles. In the case of disagreement, both reviewers read the article and discussed it until a consensus was reached.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Types of studies: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, experimental and observational studies, human studies | Articles that were not in English; studies that did not report age; studies that included participants with mental health issues prior to COVID-19 |

| Types of Participants: Studies carried out with children and adolescents (3 to 19 years old) from 2021 to 2022 | |

| Interventions: Children and adolescents impacted by COVID-19 and its repercussions on mental health | |

| Types of results: Rates of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents in times of COVID-19 | |

| Secondary outcomes: Fear, anguish, pain and psychic suffering related to the pandemic |

Relevant data were extracted from each study, including year and country of publication, study design, target population, pandemic exposure, interventions, and outcomes (Table 2). One reviewer (NNRL) used a form that the research team developed to extract the data. A second reviewer (AOAR) verified the entire data extraction activity and verified its accuracy and completeness. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Target population | Total participants | Exposure | Outcomes |

| Barros et al[19], 2022 | Brazil | Cross-sectional-electronic questionnaire | 12-17 years | 9470 adolescents | COVID-19 | The data showed that factors such as: Family problems, female gender, age 15-17 years, learning disabilities, relatives infected with COVID-19, and death of close friends from COVID-19 were factors associated with worsening mental health |

| Okuyama et al[1], 2021 | Japan | Review | Children under 18 years | Studies included (n = 28) | COVID-19 | Studies have shown correlation between physical activity and psychological health and sedentary time leading to mood disorders. Some studies on adolescents reported a correlation between physical activity and psychological health and others did not |

| Demaria and Vicari[2], 2021 | Italy | Commentary | NA | NA | COVID-19 | The pandemic context, with regard to quarantine, proved to be a psychologically stressful experience |

| Sayed et al[3], 2021 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional-online via social media | 12.25 ± 3.77 years | 537 children (263 boys and 275 girls) | COVID-19 | The data showed that Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms were not correlated with school grade, sex, age or having a close relative working with people infected by COVID-19 |

| Meherali et al[4], 2021 | Canada, Pakistan, Australia | Systematic reviews | 5-19 years | Studies included (n = 18) | COVID-19 | These studies reported that pandemics cause stress, worry, helplessness, and social and risky behavioral problems among children and adolescents |

| Bussières et al[5], 2021 | Canada | Meta-analysis | 5-13 years | Studies included (n = 28) | COVID-19 | During the COVID-19 pandemic, the restriction measures imposed had an impact on children’s mental health. During this period, there was also a change in sleep habits. Even so, the results do not show significant differences in relation to the general population |

| Bentenuto et al[6], 2021 | Italy | Retrospective | Children with NDD and TD | Total 164 (NND 82 and TD 82) | COVID-19 | Quantitative analyzes demonstrated an increase in children’s externalizing behaviors and parental stress. However, they also showed that parents enjoyed spending more time with their children and strengthening the parent-child relationship. Furthermore, in children with NDD, the reduction in therapeutic measures predisposes to high externalizing behaviors |

| Burnett et al[7], 2021 | Sweden, Australia, Italy | Cross-sectional-online self-reported survey | Parents of children aged 3-18 years | Australia (n = 196); Italy (n = 200) | COVID-19 | When compared to other developmental disorders among parents in Australia and Italy, intellectual or learning disorders are the ones that bring them the most suffering |

| Raffagnato et al[8], 2021 | Italy | Longitudinal | Psychiatric patients age between 6 and 18 years and their parents | 39 patients and their parents (25 girls and 14 boys) | COVID-19 | Patients with behavioral disorders were more impacted when compared to patients with internalizing disorders, who were shown to have adapted better to the pandemic context. In parents, it was possible to observe a protective factor against psychological maladjustment. A decrease in mothers’ anxiety and fathers’ stress over time was also observed |

| Kerr et al[9], 2021 | United States | Cross-sectional-online survey | Parents with at least one child 12 years old or younger | 1000 participants | COVID-19 | As for the psychological impacts, the data show high levels of stress and low levels of positive behavior in children, and a high rate of parental exhaustion. Still, there is an indirect association between parental behavior and the psychological impacts of COVID-19 and children’s behaviors. The data also showed that the difference in income is a factor that can increase this indirect association |

| Sesso et al[10], 2021 | Italy | Cross-sectional-online questionnaire | Parents of children 6.62 ± 3.12 years with neuropsychiatric disorders | 77 participants | COVID-19 | Internalizing problems in children during quarantine were the strongest predictor of parental stress |

| Li and Zhou[11], 2021 | China | Cross-sectional-online questionnaire | 5-8 years: 647 children; 9-13 years: 245 adolescents | 892 valid questionnaires (mothers 662 and fathers 230) | COVID-19 | Concerning the data, it was possible to observe that parents are worried about their children’s internalization and externalization problems. It was observed that, in elementary school, significant and negative relationships were observed between family-based disaster education and internalizing and externalizing problems |

| Bate et al[12], 2021 | United States | Cross-sectional-online via social media | Parents of children (6-12 years) | 158 parents of children (151 mothers and 7 fathers) | COVID-19 | It was observed that the biggest EH problems of parents were due to the impact of COVID-19. Parents’ EH was a positive predictor of children’s EBH |

| Kim et al[13], 2021 | Suwon, South Korea | Cross-sectional-web based questionnaire | Parents of children aged 7-12 years | 217 parents | COVID-19 | With schools closed, children had body weight gain, spent less time doing physical activities and more time using the media. In addition, an association can be observed between parental depression and children’s sleep problems, TV time, tablet time and behavior problems |

| Minozzi et al[14], 2021 | Italy | Systematic review | Pre-school children, children 5-12 years and adolescents | Studies included (n = 64) | COVID-19 | Studies have reported an increase in suicides, reduced access to psychiatric emergency services, reduction in allegations of maltreatment. The prevalence of anxiety among adolescents varied considerably, as did depression, although in a lower percentage |

| Backer et al[15], 2021 | Netherlands | Cross-sectional-questionnaire | 0-4, 5-9, 10-19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, 80-89 and ≥ 90 years | 7250 participants | COVID-19 | During the physical distancing restriction measures, it is possible to observe that community contacts in all age groups were restricted to an average of 5 contacts. After relaxation, it was observed that the children returned to maintain their normal contact number, while the elderly maintained their restricted contact numbers |

| Qin et al[16], 2021 | Guangdong province, China | Cross-sectional-electronic questionnaire | School-aged students [12.04 (3.01) years] | 1 199 320 children and adolescents | COVID-19 | Among those who reported psychological distress, the risk of psychological distress was analyzed among high school and elementary school students, among students who never used a mask and those who did, and among students who spent less than 0.5 h exercising and those who spent more than 1 h |

| Lu et al[17], 2021 | China, United Kingdom | Systematic review and meta-analysis | children and adolescents (0-18 years) | Studies included (n = 23) | COVID-19 | Studies show a combined prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and post-traumatic stress symptoms |

| Ma et al[18], 2021 | China, United States | Cross-sectional-online self-report questionnaires | 6-8 years | 17740 children and adolescents | COVID-19 | The data reported that depressive, anxiety, compulsive, inattentive and sleep-related problems were more expressive when compared to before the COVID-19 outbreak |

| Spencer et al[23], 2021 | United States | Cohort study | 5-11 years | Caregivers of 168 children (54% non-Hispanic black, 29% Hispanic, and 22% non-English speaking) | COVID-19 | Children had significantly higher emotional and behavioral symptoms mid-pandemic vs pre-pandemic in all scenarios |

| Han and Song[20], 2021 | South Korea | Retrospective | Middle and high school students | 54948 students | COVID-19 | The data showed, through multivariate logistic regression, that there was a correlation between the perception of the economic situation of the family and the prevalence of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation |

| Giannakopoulos et al[21], 2021 | Greece | Quality study-interviews | 12-17 years | 09 psychiatric inpatients | COVID-19 | Patients identified that the state of quarantine caused negative changes in personal freedom and social life, as well as excessive contact with family members during social isolation |

| Almhizai et al[22], 2021 | Saudi Arabia | Cross sectional study-online self-administered questionnaire | 0-17 years | 1141 respondents, 454 were < 18 years old and 688 children’s parents | COVID-19 | Among the data presented, age was a factor for sleep disorders, nervousness and malaise; aggressive behaviors were also associated with an increase in negative behaviors during the pandemic compared to the previous period |

| Maunula et al[24], 2021 | Northern prairie communities, Canada | Multi-method study, focus groups, and interviews | Children grade 4-6 and their parents | 31 patients (16 children and 15 parents) | COVID-19 | Children were subjected to sudden and stressful changes in their routines. In addition, loneliness and increased screen time were a result of limited social interaction |

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Assessment Tool.

Data were aggregated and analyzed according to the results and objectives of the study. Therefore, the results were summarized according to the reported results and the study design (Table 2).

The likelihood of a treatment effect reported in systematic reviews resembling the truth depends on the validity of the studies included in the analysis as certain methodological characteristics may be associated with effect sizes. Therefore, it was important to determine in the systematic reviews whether the sample of studies obtained was representative of all the research carried out on depression in childhood and adolescence in times of COVID-19. The possibility of bias resulting from a trend of only positive findings being published-known as the “file drawer effect”-was addressed using two methods: Calculating the fail-safe N and the p-curve approach.

The fail-safe N is determined by calculating the number of studies with a mean null result needed to make the overall results insignificant. The p-curve was introduced to account for “p-hacking”, a theory stating that researchers may be able to get most studies to find positive results across different reviews. The p-curve assesses the slope of the reported p-values to determine whether p-hacking has occurred.

The most significant findings of depression in children and adolescents impacted by COVID-19 were found in 24 studies, which required the p-value to be set at > 0.05. In addition, quarantine, sleep disturbances, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and the prevalence of anxiety were findings that validated the results. The p-curve was applied to explain p-hacking-to guarantee positive results. When calculating the p-curve, only 13 studies were included that examined the psychiatric impact on adolescents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic[2,3,6,7,15-23]. The studies existing in the literature (P = 0.5328) indicating depression among children and adolescents have sufficient evidence in their findings, particularly because there were 11 studies on potential interventions to improve the mental health of children and adolescents[1,4,5,8,9-13,23,24].

Clearly, solutions to the file drawer problem present an irritating and challenging issue for meta-analytic research and it will likely take a paradigm shift to truly address this problem, as authors who submit their literature reviews and methods only, abandoning conventional inferential statistics in favor of Bayesian Approaches, or the registration of studies and protocols online before conducting a study.

The search identified 325 articles, but 125 duplicates were removed. Therefore, 200 articles were selected, chosen by the title and abstract. Fifty articles were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Consequently, a total of 150 articles were selected to be read in full. After that, 91 text articles were excluded, with 24 being selected for the final (n) (Figure 1).

We analyzed the studies thematically and divided them into two categories: (1) Psychiatric impact on children and adolescents in times of COVID-19; and (2) potential interventions to improve the mental health of children and adolescents.

Among the studies included, 13 examined the psychiatric impact on children and adolescents in times of COVID-19[2,3,6,7,14-22].

A research study by Demaria and Vicari[2] and Sayed et al[3] showed that quarantine is a psychologically stressful experience. For children, missing school and interruptions in daily routines can have a negative impact on their physical and mental health. In this perspective, they pointed out that parents could also pass on their psychological suffering to children and parent them inappropriately, contributing to the development of post-traumatic stress symptoms. In addition, if the C-A has a mental disorder, the psychic suffering of the parents tends to be greater and depends on the way children externalize their emotions[6,7].

Minozzi et al[14] highlight high rates of anxiety and depression among C-A. Among preschool children, they found aggravation of behavioral and emotional problems, while others did not. They found that psychological well-being had significantly worsened, especially among adolescents. Backer et al[15] demonstrate that the reduced number of social contacts associated with strict social distancing measures contributes to inflicting pain and psychic suffering in children and adolescents. The authors also point out that not wearing a mask; being a high school student[15] and spending less than 0.5 h exercising were positively associated with increased psychological distress[16].

A meta-analysis of 23 studies (n = 57927 children and adolescents from Turkey and China) showed combined prevalence of anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, sleep disorders and depression. In addition, female sex and adolescents were more associated with depressive and/or anxious symptoms when compared to male sex or children, respectively[18].

Barros et al[19] showed high rates of nervousness (48.7%) and sadness (32.4%) among Brazilian adolescents. Individuals aged between 15-17 years; being female; having learning difficulties during the pandemic; having a family that faces financial difficulties; and individuals who previously had trouble sleeping or poor health were the most affected. In the study by Han and Song[20] economic difficulties during the pandemic were correlated with depression and suicidal ideation. Concerning their emotions, adolescents recognized anxiety about self-harm and harm to their loved ones, as well as mood swings in the family nucleus[21].

Globally, the increase in drug abuse has also been mapped in the literature, with alcohol and marijuana being the most used[7]. Almhizai et al[22] showed that the older age of children and adolescents was a risk factor for sleep disorders, malaise, and nervousness. The presence of a relative infected with COVID-19 was also associated with higher rates of anxiety, irritability, sadness, and sleep disorders. Finally, physical punishment and verbal threats had a more negative impact on the mental health promotion of C-A when compared to the pre-pandemic period.

Eleven studies reported potential interventions to improve the mental health of children and adolescents[1,4,5,8-13,23,24].

Bussières et al[5] showed no association between the presence of previous chronic diseases (including NDD) and negative symptoms during the pandemic. Raffagnato et al[8] highlight that patients with internalizing disorders had better adaptation and lower rates of psychological distress when compared to patients with psychological distress.

In addition, the worsening of parents’ mental health[10], school-age children belonging to urban racial and ethnical minorities[23], and physical inactivity[1,17] had a negative impact on the health of children and adolescents. Data from Li and Zhou[11] suggest that children less exposed to parental concerns (e.g., about finances, health and education) were less likely to have internalizing and externalizing problems[11]. It is crucial to promote family well-being through political practices and initiatives, including providing financial and care assistance to parents and supporting the mental and behavioral health of families[9]. In addition to focusing on symptom management, families can benefit from support aimed at the parent-child relationship. Insights and implications for practitioners are discussed[12]. Finally, promoting coping strategies for children and adolescents to deal with extreme situations (e.g., pandemics, wars, and natural disasters) is fundamental. Especially if the strategies encompass the communities/schools the children/adolescents attend[24].

The rapid spread of COVID-19 has significantly influenced the psychological state of children and adolescents. It is clear that poverty[19,20], hunger, housing insecurity, domestic violence, and sexual abuse[19], black children and adolescents, and homeless people living in favelas, especially older adolescents, need urgent mental health support. The physical restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic and the social distancing measures have affected all domains of life. Anxiety, depression, drug abuse, sleep and appetite disorders, as well as impaired social interactions, are the most common presentations[4,13].

The frequency of mask use and time spent on schoolwork were factors associated with good mental health[16]. The prevalence of depression ranges from 13.5% to 81.0%. Analysis by age indicated that the prevalence of depression is higher in children aged 5-9 years and adolescents aged 12-18 years. Analysis by gender showed that the prevalence of depression in females was higher than in males. The prevalence of anxiety among children and adolescents was 45.6%. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms is statistically higher in vulnerable and/or socially at-risk children and adolescents. The prevalence of sleep disorders varies according to the stressor involved in family ties and the way they face COVID-19, as well as the economic situation and the healthcare system, which vary greatly between countries[17]. Parental anxiety has the greatest influence on a child’s psychological symptoms, explaining about 33% of the variation in a child’s overall symptoms[18,23].

Most studies point to negative symptoms being caused by social distancing in children and adolescents of vulnerable families, including restrictions on social life and personal freedom, as well as excessive contact with family members during stay-at-home periods[1,2,21].

It is important to highlight that children and adolescents in extreme poverty report a wide range of negative thoughts associated with the pandemic (for example, abandonment, helplessness, sadness, anguish, anxiety, and feelings of panic). The thoughts and feelings of such teenagers can be triggered by the fact that their survival is threatened[4,5].

Special populations, especially lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) adolescents, have higher rates of pain and psychological distress that lead to anxiety, depression, compulsion, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Additionally, coming into conflicts with parents due to gender issues is observed in the literature as a factor that worsens mental health in this population[7,22].

Due to the short data collection period, from 2021 to 2022, relevant studies on how to care for the mental health of children and adolescents may be lacking. In addition, there is the possibility of publication bias, i.e., only significant findings being published.

Fear, anxiety, panic, depression, insomnia and appetite disorders, as well as impaired routine caused by psychic stress, are individual markers of pain and psychic suffering, which have increasing impacts on the mental health panorama of children and adolescents. A better understanding of the psychological pathways available is necessary to help clinicians, researchers, and decision makers prevent the deterioration of mental and general functioning disorders, as well as other stress-related disorders in children and adolescents[2,4,6,13].

Agreeing with Giannakopoulos et al[21] and Barros et al[19] professionals should continue to provide strategies to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of children, adolescents and their families, aiming at improving the quality of life and rehabilitation in the post-pandemic period. It is necessary to emphasize the need to build resilience and promote strategies to manage negative feelings during crises (environmental, social, political, and economic)[24].

The authors are grateful to the Faculty of Medicine-University of São Paulo (USP), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) linked to the Brazilian Ministry of Education, Doctoral Program in Neuroscience and Human Development-Logos University International-UNILOGOS, Miami, FL, United States of America and Universidade Estácio-IDOMED.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Piccinelli MP, Italy; Wang CX, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Okuyama J, Seto S, Fukuda Y, Funakoshi S, Amae S, Onobe J, Izumi S, Ito K, Imamura F. Mental Health and Physical Activity among Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2021;253:203-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Demaria F, Vicari S. COVID-19 quarantine: Psychological impact and support for children and parents. Ital J Pediatr. 2021;47:58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sayed MH, Hegazi MA, El-Baz MS, Alahmadi TS, Zubairi NA, Altuwiriqi MA, Saeedi FA, Atwah AF, Abdulhaq NM, Almurashi SH. COVID-19 related posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents in Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Meherali S, Punjani N, Louie-Poon S, Abdul Rahim K, Das JK, Salam RA, Lassi ZS. Mental Health of Children and Adolescents Amidst COVID-19 and Past Pandemics: A Rapid Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 102.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bussières EL, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, Meilleur A, Mastine T, Hérault E, Chadi N, Montreuil M, Généreux M, Camden C; PRISME-COVID Team. Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children's Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:691659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bentenuto A, Mazzoni N, Giannotti M, Venuti P, de Falco S. Psychological impact of Covid-19 pandemic in Italian families of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;109:103840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Burnett D, Masi A, Mendoza Diaz A, Rizzo R, Lin PI, Eapen V. Distress Levels of Parents of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparison between Italy and Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Raffagnato A, Iannattone S, Tascini B, Venchiarutti M, Broggio A, Zanato S, Traverso A, Mascoli C, Manganiello A, Miscioscia M, Gatta M. The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study on the Emotional-Behavioral Sequelae for Children and Adolescents with Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Their Families. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kerr ML, Fanning KA, Huynh T, Botto I, Kim CN. Parents' Self-Reported Psychological Impacts of COVID-19: Associations With Parental Burnout, Child Behavior, and Income. J Pediatr Psychol. 2021;46:1162-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sesso G, Bonaventura E, Buchignani B, Della Vecchia S, Fedi C, Gazzillo M, Micomonaco J, Salvati A, Conti E, Cioni G, Muratori F, Masi G, Milone A, Battini R. Parental Distress in the Time of COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study on Pediatric Patients with Neuropsychiatric Conditions during Lockdown. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li X, Zhou S. Parental worry, family-based disaster education and children's internalizing and externalizing problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13:486-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bate J, Pham PT, Borelli JL. Be My Safe Haven: Parent-Child Relationships and Emotional Health During COVID-19. J Pediatr Psychol. 2021;46:624-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim SJ, Lee S, Han H, Jung J, Yang SJ, Shin Y. Parental Mental Health and Children's Behaviors and Media Usage during COVID-19-Related School Closures. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36:e184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Minozzi S, Saulle R, Amato L, Davoli M. [Impact of social distancing for covid-19 on the psychological well-being of youths: a systematic review of the literature.]. Recenti Prog Med. 2021;112:360-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Backer JA, Mollema L, Vos ER, Klinkenberg D, van der Klis FR, de Melker HE, van den Hof S, Wallinga J. Impact of physical distancing measures against COVID-19 on contacts and mixing patterns: repeated cross-sectional surveys, the Netherlands, 2016-17, April 2020 and June 2020. Euro Surveill. 2021;26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Qin Z, Shi L, Xue Y, Lin H, Zhang J, Liang P, Lu Z, Wu M, Chen Y, Zheng X, Qian Y, Ouyang P, Zhang R, Yi X, Zhang C. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated With Self-reported Psychological Distress Among Children and Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2035487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ma L, Mazidi M, Li K, Li Y, Chen S, Kirwan R, Zhou H, Yan N, Rahman A, Wang W, Wang Y. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:78-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 71.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ma J, Ding J, Hu J, Wang K, Xiao S, Luo T, Yu S, Liu C, Xu Y, Liu Y, Wang C, Guo S, Yang X, Song H, Geng Y, Jin Y, Chen H. Children and Adolescents' Psychological Well-Being Became Worse in Heavily Hit Chinese Provinces during the COVID-19 Epidemic. J Psychiatr Brain Sci. 2021;6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Barros MBA, Lima MG, Malta DC, Azevedo RCS, Fehlberg BK, Souza Júnior PRB, Azevedo LO, Machado ÍE, Gomes CS, Romero DE, Damacena GN, Werneck AO, Silva DRPD, Almeida WDS, Szwarcwald CL. Mental health of Brazilian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res Commun. 2022;2:100015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Han JM, Song H. Effect of Subjective Economic Status During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation Among South Korean Adolescents. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:2035-2043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Giannakopoulos G, Mylona S, Zisimopoulou A, Belivanaki M, Charitaki S, Kolaitis G. Perceptions, emotional reactions and needs of adolescent psychiatric inpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative analysis of in-depth interviews. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Almhizai RA, Almogren SH, Altwijery NA, Alanazi BA, Al Dera NM, Alzahrani SS, Alabdulkarim SM. Impact of COVID-19 on Children's and Adolescent's Mental Health in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2021;13:e19786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Spencer AE, Oblath R, Dayal R, Loubeau JK, Lejeune J, Sikov J, Savage M, Posse C, Jain S, Zolli N, Baul TD, Ladino V, Ji C, Kabrt J, Mousad L, Rabin M, Murphy JM, Garg A. Changes in psychosocial functioning among urban, school-age children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2021;15:73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Maunula L, Dabravolskaj J, Maximova K, Sim S, Willows N, Newton AS, Veugelers PJ. "It's Very Stressful for Children": Elementary School-Aged Children's Psychological Wellbeing during COVID-19 in Canada. Children (Basel). 2021;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |