Published online Jul 19, 2021. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i7.375

Peer-review started: February 8, 2021

First decision: March 30, 2021

Revised: April 9, 2021

Accepted: June 16, 2021

Article in press: June 16, 2021

Published online: July 19, 2021

Processing time: 157 Days and 1.2 Hours

Grouping eating disorders (ED) patients into subtypes could help improve the establishment of more effective diagnostic and treatment strategies.

To identify clinically meaningful subgroups among subjects with ED using multiple correspondence analysis (MCA).

A prospective cohort study was conducted of all outpatients diagnosed for an ED at an Eating Disorders Outpatient Clinic to characterize groups of patients with ED into subtypes according to sociodemographic and psychosocial impairment data, and to validate the results using several illustrative variables. In all, 176 (72.13%) patients completed five questionnaires (clinical impairment assessment, eating attitudes test-12, ED-short form health-related quality of life, metacognitions questionnaire, Penn State Worry Questionnaire) and sociodemographic data. ED patient groups were defined using MCA and cluster analysis. Results were validated using key outcomes of subtypes of ED.

Four ED subgroups were identified based on the sociodemographic and psychosocial impairment data.

ED patients were differentiated into well-defined outcome groups according to specific clusters of compensating behaviours.

Core Tip: This is the first study to apply multiple correspondence analysis to eating disorders (ED) diagnostic data and to use cluster analysis (CA) in such detail to search for ED patient groups in this area. Multiple correspondence analysis and CA made it possible to identify different typologies of patients with specific features. Grouping ED patients into subtypes could help improve the establishment of more effective strategies of diagnosis and treatment, and improve patient care and prognosis in clinical practice.

- Citation: Martín J, Anton-Ladislao A, Padierna Á, Berjano B, Quintana JM. Classification of subtypes of patients with eating disorders by correspondence analysis. World J Psychiatr 2021; 11(7): 375-387

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v11/i7/375.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v11.i7.375

Eating disorders (ED) are serious psychiatric conditions; clinical presentations of persons with ED[1,2] vary substantially and they may be associated with many factors, e.g., sociodemographic as gender[3] or clinical as personality profiles[4]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-5[5] aims to better capture the presentations of ED symptoms observed by modifying previous ED diagnostic criteria. However, as Turner et al[6] have, noted some researchers remain concerned, that these adjustments will fail adequately to address the substantial heterogeneity in clinical presentations amongst patients with ED[1]. It is important to research subtypes of ED, since otherwise the field might merely end up ‘studying what it defines’ (or failing to study anything it does not define)[7]. Thus, removing any reference to non-purging compensatory behaviors would reinforce the impression-(created by subtyping) that bulimic-type ED characterized by purging behaviors is more severe than that involving non-purging behaviors when there is actually little empirical evidence to support this view[7,8]. Insofar as distinct subgroups of ED patients can be reliably identified, it is possible that these groupings might be used to inform assessment, treatment and future diagnostic nosologies[9]. Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) is an exploratory technique that offers descriptive patterns based on the categories of the original active variables[10,11]. It transforms the information on the categorical active variables into continuous factors. The relative positions of the categories given by the MCA factors are used to perform the cluster analysis (CA) which classifies information into relatively homogenous groups. By combining MCA and CA it might be possible to arrive at a classification of the subjects suggested by the data, rather than defined a priori, where subjects in each group are similar to one another but dissimilar to those of other groups[10,12].

Grouping ED patients into subtypes could help improve the establishment of more effective strategies of diagnosis and treatment, and improve patient care and prognosis in clinical practice. The aim of this study was to identify ED patient subtypes. To this end, MCA and CA statistical techniques were combined to analyze clinical data obtained in a prospective cohort study of ED patients treated in an ED Outpatient Clinic. The subtypes were then validated by estimating their relationships to key outcomes such as health-related quality of life (HRQoL), psychosocial impairment due to ED, worry and metacognitions, eating problems, and sociodemographic variables.

A prospective cohort study was conducted of all patients diagnosed with and treated for an ED at the Eating Disorders Outpatient Clinic The clinic forms part of the psychiatric services at the hospital, which serves a population of 300000. It is part of the Basque Health Care Service, which provides unlimited free care to nearly 100% of the population. Outpatients recruited between January 2010 and January 2011 were considered eligible for the study if they had received a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), or an ED not otherwise specified (EDNOS) by a psychiatrist, on the basis of the criteria listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition text revision[5]. Patients were required to provide written informed consent before participating. They were excluded if they had a malignant, severe organic disease were unable to complete the questionnaires because of languagedifficulties, or had not given their written informed consent to participate in the study.

The study received approval from the institutional review board of the Hospital.

ED patients gave their sociodemographic data, including age, gender, marital status, education, employment status, and living situation.

The clinical impairment assessment (CIA v.3.0)[13,14] is a 16-item self-report instrument specifically designed to assess psychosocial impairment secondary to features of an ED. A higher score indicates greater impairment. The CIA report of psychometric properties indicated that the measure was both adequate and valid[13,15].

Eating pathologies were measured using the eating attitudes test-12 (EAT-12)[16]. This is a 12-item instrument, which uses a 4-point scale, with scores from 0 (never) to 3 (always). Higher scores indicate more disordered eating. Its validity as a measure of disordered eating has been backed by previous studies[17,18].

The quality of life of ED patients was evaluated using the health-related quality of life in ED-short form)[19] ,a 20-item questionnaire divided into two domains: social maladjustment and mental health and functionality. The lower the quality of life, the higher the score[15,20].

The metacognitions questionnaire (MCQ-30)[21] is a brief multidimensional measure of a range of metacognitive processes and metacognitive beliefs related to worry and cognition relevant to vulnerability to and maintenance of emotional disorders. Higher scores reflect a more dysfunctional metacognitive belief. The subscales have good psychometric properties[21,22].

The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ-R) is a 16-item self-report measure of trait worry that is widely used to measure pathological worry[23]. A Spanish version reduced to 11 items was used[24]. Higher scores indicate greater levels of pathological worry. The PSWQ-R has been shown to have good psychometric properties[25,26].

Data gathering began in 2010. Psychiatrists who collaborated in the study informed their patients of the aims of the study and recorded sociodemographic information. Patients agreeing participate were mailed questionnaires and an informed consent form ,which they were asked to mail back using an enclosed, pre- franked envelope. Two reminders were mailed out at 15-d intervals to patients who failed to reply to the first mailing.

Various multivariate techniques are used in order to synthesize the information contained in a large set of explanatory variables into a few components, also called factors. One of them is the technique selected for this analysis, MCA, which is designed for categorical explanatory variables, while others, as principal component analysis, are designed for continuous variables. Based on the categories of the original variables, MCA provides descriptive patterns by factors. In the continuous factors, therefore, each category of variables is represented by a numerical value and a positive/negative sign, used for interpretation. Graphical displays of these factors are very useful in interpretation, as the association between the categories is indicated by their relative position on the graph. The closer the categories are to one another, the stronger the association. Variables included in the analysis are known as active variables, whilst those not included in the analysis but used to verify the relationship with active variables are termed illustrative variables or outcomes[10]. A descriptive analysis was made of sociodemographic and psychosocial impairment data, using frequencies and percentages. Means and standard deviations were also used as additional information for questionnaires of psychosocial impairment. The active variables in the MCA were gender, age (13-25, 26-35, 35-63), marital status [single, spouse/partner, divorced/widow(er)], education completed (primary, secondary, higher), employment status (employed, unemployed, student, disabled, unpaid work/housewife), living situation (living alone, with partner/children, friends, parents/siblings), MCQ-30 questionnaire (≤ 57, 58-75, > 75), CIA questionnaire (< 16, ≥ 16), EAT-12 questionnaire (< 8, ≥ 8), HeRQoLED-SocM (≤ 50, > 50), HeRQoLED-MHF (≤ 50, > 50) and PSWQ-R (≤ 28, > 28). Type (AN, BN and EDNOS) and subtype (restrictive, purgative and binge) of ED patients were used as illustrative variables.

For classification purposes, CA organizes information into relatively homogeneous groups based on their values in a range of variables — in this case, based on the factors derived from the MCA. In other words, the objective of the CA is to assign individuals into different groups, in the way that individuals from the same group are similar to each other, but dissimilar from individuals of other groups. The number of groups derived from the CA is selected using the minimum inertia lost method[27].

The association between the active variables and the groups derived from the CA was evaluated using the chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test when expected frequencies were less than 5). The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used for the scores of the psychosocial impairment questionnaires. In addition, the relationship of outcomes or illustrative variables was evaluated according to the groups obtained from the CA. In order to see the stability of the groups obtained and since we had all the active variables measured at 12 mo of follow up too, the same analysis was replicated with the variables at 12 mo of follow up. Statistical analyses were carried out with R v3.0.2 and SAS 9.4 software (copyright, SAS Institute Inc.). “SAS” and the names of all other SAS Institute Inc. products and services are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital. Written consent for participation was obtained. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02483117. All methods were used in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

A total of 244 patients with ED were invited to take part in the study. Of these, 176 filled out the questionnaires. Early dropouts were largely due to patients failing to consent to participation. The mean of the CIA questionnaire was 19.5 (SD 13.6), which indicates a high level of impairment due to ED.

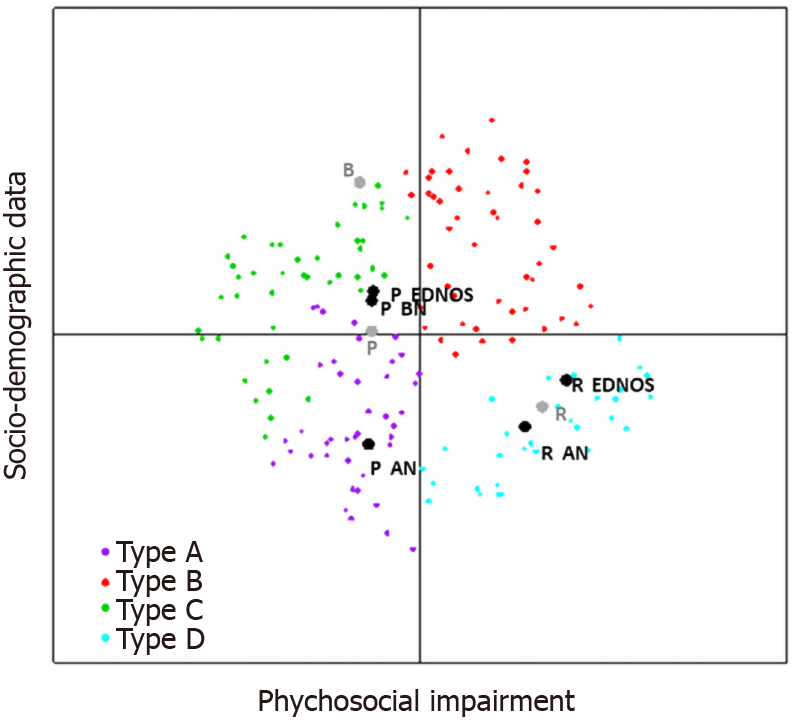

Results from the MCA showed that 74% of data variability could be explained by two factors, the first primarily associated with the HRQoL and the second with socio-demographic data. Figure 1 shows the map created by the first and second factors. The first factor is represented on the horizontal axis and the second on the vertical axis. Variables that were well-represented in the first factor were: the questionnaires related to psychosocial impairment; eating problems; HRQoL; worry; and metacognitions. Categories located in the positive part (right) of the map included lower values at CIA, EAT-12, HeRQoLED-s, MCQ-30, PSWQ. In contrast, higher values of the questionnaires were in the negative part (left). This axis was defined as “Psychosocial impairment: from high to low”.Moreover, the relative position of the illustrative variables on the graph indicates that some subtypes of diagnosis according to compensatory behaviour as well as some subtypes of diagnosis related to DSM-IV-TR classification were well represented by this factor. Indeed, restrictive behaviour (AN, EDNOS) was located in the right side of the axis, whereas purgative behaviour (BN, EDNOS) stood on the left of the axis. The variables that were well-represented in the second factor were socio-demographic variables. Categories such as being male, having a spouse, having secondary studies, being a housewife and living with a partner/children were related to the positive part (top). In contrast, the categories of being single, having higher studies, being a student and living with friends or parents or/and a sibling, were related to the negative part of the axis (bottom). This axis was therefore interpreted as “socio-demographic data”. As in the other axis, some categories of the illustrative variables were well-represented by this axis. Purgative AN was located in the negative part, while binge behaviour (only in patients with EDNOS diagnosis) was located in the positive part.

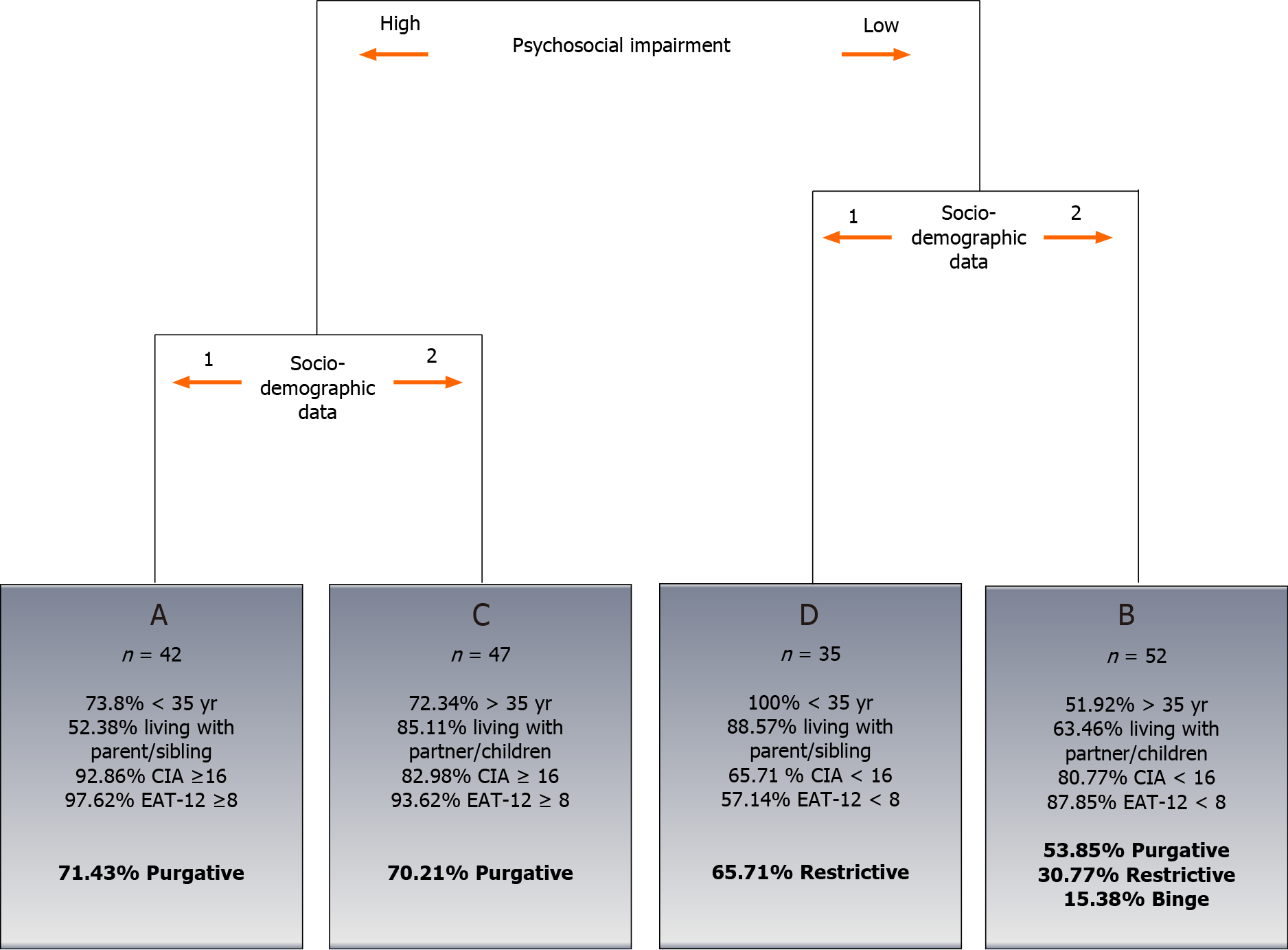

Following application of CA to the factors derived from the MCA, four ED patient types were identified (Figure 2) and labelled from A to D. Types A and C were patients with high psychosocial impairment, while types B and D were patients with low psychosocial impairment. However, types A and C, and B and D, differed in their socio-demographic characteristics. Figure 3 shows the two-dimensional distribution resulting from graphing the first and second factors. Types were represented by colours and the relative positions of the two illustrative variables were projected on the graph.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the variables collected for all ED patients across the four ED subtypes. Statistically significant differences between subtypes were observed in all socio-demographic and psychosocial impairment variables, except for gender. Table 2 shows the associations between the subtypes and the illustrative variables and subtypes. Among patients in subtypes A (n = 42) and C (n = 47), 71.43% and 70.21% respectively had purgative behaviours. Subtype D included 35 patients, of whom 65.71% had restrictive behaviours. Among the 52 patients in subtype B, 58.85% had purgative behaviours, 30.77% had restrictive behaviours, and 15.38% had binge behaviours. The distribution of patients across the subtypes was significantly associated with the illustrative variable (P < 0.0001). In order to see the stability of the groups obtained in another way, results at 12 mo of follow-up showed that factors created by the MCA with the 12 mo follow-up data were the same as in the baseline (see material online, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary Figure 1). So, the characteristics that define the groups derived from the CA (A, B, C, D) are stable. Table 3 shows the differences in quality of life among the three groups defined in the literature (AN, BN and EDNOS).

| n (%) | Type of patient | P value | |||||||

| A | B | C | D | ||||||

| Active variables | 176 | 42 (23.86) | 52 (29.55) | 47 (26.70) | 35 (19.89) | ||||

| Sociodemographic variables | |||||||||

| Gender (Female) | 166 (94.32) | 42 (100) | 47 (90.38) | 44 (93.62) | 33 (94.29) | 0.25 | |||

| Age | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| ≤ 25 | 42 (23.86) | 9 (21.43) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 33 (94.29) | ||||

| 26-35 | 62 (35.23) | 22 (52.38) | 25 (48.08) | 13 (27.66) | 2 (5.71) | ||||

| > 35 | 72 (40.91) | 11 (26.19) | 27 (51.92) | 34 (72.34) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Marital status | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Single | 102 (57.95) | 36 (85.71) | 26 (50.00) | 6 (12.77) | 34 (97.14) | ||||

| Spouse/partner | 64 (36.36) | 5 (11.90) | 25 (48.08) | 33 (70.21) | 1 (2.86) | ||||

| Divorced/Widow(er) | 10 (5.68) | 1 (2.38) | 1 (1.92) | 8 (17.02) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Educational level | 0.007 | ||||||||

| Primary education | 36 (20.45) | 7 (16.67) | 12 (23.08) | 10 (21.28) | 7 (20.00) | ||||

| Secondary education | 56 (31.82) | 7 (16.67) | 17 (32.69) | 24 (51.06) | 8 (22.86) | ||||

| Higher education | 84 (47.73) | 28 (66.67) | 23 (44.23) | 13 (27.66) | 20 (57.14) | ||||

| Employment status | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Employed | 72 (40.91) | 20 (47.62) | 33 (63.46) | 17 (36.17) | 2 (5.71) | ||||

| Unemployed | 25 (14.20) | 11 (26.19) | 8 (15.38) | 6 (12.77) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Student | 41 (23.30) | 6 (14.29) | 2 (3.85) | 0 (0) | 33 (94.29) | ||||

| Disabled | 18 (10.23) | 4 (9.52) | 2 (3.85) | 12 (25.53) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Non-paid work/housewife | 20 (11.36) | 1 (2.38) | 7 (13.46) | 12 (25.53) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Living situation | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Alone | 13 (7.39) | 4 (9.52) | 5 (9.62) | 3 (6.38) | 1 (2.86) | ||||

| Partner/children | 82 (46.59) | 8 (19.05) | 33 (63.46) | 40 (85.11) | 1 (2.86) | ||||

| Friends | 14 (7.95) | 8 (19.05) | 1 (1.92) | 3 (6.38) | 2 (5.71) | ||||

| Parents/siblings | 67 (38.07) | 22 (52.38) | 13 (25.00) | 1 (2.13) | 31 (88.57) | ||||

| Health-related quality of life variables | |||||||||

| MCQ-30 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| ≤ 57 | 59 (33.52) | 4 (9.52) | 30 (57.69) | 7 (14.89) | 18 (51.43) | ||||

| 58-75 | 58 (32.95) | 23 (54.76) | 11 (21.15) | 10 (21.28) | 14 (40.00) | ||||

| > 75 | 59 (33.52) | 15 (35.71) | 11 (21.15) | 30 (63.83) | 3 (8.57) | ||||

| MCQ-301 | 67.0 (18.5) | 72.2 (12.4)BD | 57.6 (18.6)AC | 78.4 (18.4)BD | 58.6 (12.8)AC | < 0.0001 | |||

| CIA (≥ 16) | 100 (56.82) | 39 (92.86) | 10 (19.23) | 39 (82.98) | 12 (34.29) | < 0.0001 | |||

| CIA1 | 19.5 (13.6) | 30.7 (9.6)BD | 9.2 (8.0)AC | 26.0 (12.8)BD | 12.2 (9.2)AC | < 0.0001 | |||

| EAT-12 (≥ 8) | 111 (63.07) | 41 (97.62) | 11 (21.15) | 44 (93.62) | 15 (42.86) | < 0.0001 | |||

| EAT-121 | 10.7 (7.5) | 16.4 (5.9)BD | 4.9 (4.6)AC | 14.1 (6.2)BD | 7.6 (6.2)AC | < 0.0001 | |||

| HeRQoLED-s | |||||||||

| SocM (> 50) | 84 (47.73) | 35 (83.33) | 4 (7.69) | 35 (74.47) | 10 (28.57) | < 0.0001 | |||

| SocM1 | 48.1 (24.0) | 63.9 (16.4)BD | 29.0 (15.8)AC | 63.1 (19.4)BD | 36.6 (20.6)AC | < 0.0001 | |||

| MHF (> 50) | 61 (34.66) | 28 (66.67) | 2 (3.85) | 25 (53.19) | 6 (17.14) | < 0.0001 | |||

| MHF1 | 43.5 (21.7) | 56.8 (17.8)BD | 29.0 (15.2)AC | 56.9 (17.8)BD | 30.4 (17.0)AC | < 0.0001 | |||

| PSWQ-R (> 28) | 110 (62.50) | 38 (90.48) | 18 (34.62) | 39 (82.98) | 15 (42.86) | < 0.0001 | |||

| PSWQ-R1 | 29.7 (8.3) | 34.8 (4.1)BD | 24.4 (8.4)AC | 33.6 (5.9)BD | 25.9 (8.2)AC | < 0.0001 | |||

| n (%) | Type of patient | P value | ||||

| A | B | C | D | |||

| Illustrative variables | ||||||

| Type of ED | 0.11 | |||||

| AN | 53 (30.11) | 17 (40.48) | 13 (25.00) | 8 (17.02) | 15 (42.86) | |

| BN | 34 (19.32) | 6 (14.29) | 10 (19.23) | 13 (27.66) | 5 (14.29) | |

| EDNOS | 89 (50.57) | 19 (45.24) | 29 (55.77) | 26 (55.32) | 15 (42.86) | |

| Subtype of ED | < 0.0001 | |||||

| Restrictive | 51 (28.98) | 8 (19.05) | 16 (30.77) | 4 (8.51) | 23 (65.71) | |

| Purgative | 103 (58.52) | 30 (71.43) | 28 (53.85) | 33 (70.21) | 12 (34.29) | |

| Binge | 22 (12.50) | 4 (9.52) | 8 (15.38) | 10 (21.28) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | Type of ED | P value | |||

| n (%) | AN, n (%) | BN, n (%) | EDNOS, n (%) | ||

| Health-related quality of life variables | 176 | 53 (30.11) | 34 (19.32) | 89 (50.57) | |

| MCQ-30 | 0.25 | ||||

| ≤ 57 | 59 (33.52) | 17 (32.08) | 8 (23.53) | 34 (38.20) | |

| 58-75 | 58 (32.95) | 22 (41.51) | 11 (32.35) | 25 (28.09) | |

| > 75 | 59 (33.52) | 14 (26.42) | 15 (44.12) | 30 (33.71) | |

| MCQ-301 | 67.0 (18.5) | 65.3 (19.5) | 72.1 (18.5) | 66.1 (17.7) | 0.19 |

| CIA (≥ 16) | 100 (56.82) | 32 (60.38) | 20 (58.82) | 48 (53.93) | 0.73 |

| CIA1 | 19.5 (13.6) | 21.7 (14.4) | 21.3 (13.9) | 17.6 (12.8) | 0.17 |

| EAT-12 (≥ 8) | 111 (63.07) | 35 (66.04) | 22 (64.71) | 54 (60.67) | 0.8 |

| EAT-121 | 10.7 (7.5) | 12.9 (8.6) | 12.1 (8.1) | 8.9 (6.1) | 0.02 |

| HeRQoLED-s | |||||

| SocM (> 50) | 84 (47.73) | 25 (47.17) | 19 (55.88) | 40 (44.94) | 0.55 |

| SocM1 | 48.1 (24.0) | 48.4 (25.2) | 52.0 (25.0) | 46.5 (22.9) | 0.58 |

| MHF (> 50) | 61 (34.66) | 21 (39.62) | 12 (35.29) | 28 (31.46) | 0.61 |

| MHF1 | 43.5 (21.7) | 43.3 (24.5) | 44.2 (23.3) | 43.4 (19.5) | 0.99 |

| PSWQ-R (> 28) | 110 (62.50) | 32 (60.38) | 24 (70.59) | 54 (60.67) | 0.56 |

| PSWQ-R1 | 29.7 (8.3) | 28.6 (8.7) | 31.1 (9.0) | 29.8 (7.7) | 0.23 |

The purpose of this study was to identify clinically meaningful subgroups among subjects with ED using multiple correspondence analyses. MCA is a well-established statistical technique that is suitable for suggesting possible diagnostic categories, as seeks to identify clusters of individuals with similar features. In this study, ED outpatients can be categorized by two main components: one related to sociodemographic data (in graphical terms, shown by the second factor, in which negative values were associated with being old and living with partner/children and positive values were associated with being young and living with parents/siblings), and the other related to psychosocial impairment data (shown by the first factor, in which positive values were associated with better HRQoL and negative values were associated with worse HRQoL). In the hierarchy used, patients were first classified based on HRQoL variables, followed by the sociodemographic variables. The four subtypes (A, B, C, and D) provide a typology of ED patients.

Moreover MCA and CA made it possible to identify different typologies of patients with specific features. Types D and A were similar with regard to sociodemographic data, while Types A and C (D and C) were similar with regard to psychosocial impairment variables. In relation to the sociodemographic variables, Types D and A were characterized by being younger, having a higher education level, being single, and living with their parents or siblings. Types B and C, in contrast, were characterized by being older (> 35 years), having secondary education and living with their partner/children. According to psychosocial impairment variables, Types A and C had the most severe ED and were characterized by higher psychosocial impairment, ED severity, lower HRQoL, higher dysfunctional metacognitive belief and level of pathological worry, while Types D and B had a lower psychosocial impairment and less severe ED. As regards the diagnostic, as in this study, other research[28,29] have also failed to identify specific differences between the HRQoL effect of distinct ED diagnostic groups. With regard to the type of compensating behaviour, 65.71% of patients in Group D, and 53.85% of patients in Group B belong to the group of restrictive patients; while 71.43% of patients in Group A and 70.21% of those in Group C belong to the group of purgative patients.

These findings are consistent with those of DeJong et al[30], who explored whether purge spectrum groups have a higher degree of clinical severity than restrictive groups. Indeed, a major meta-analysis concluded that vomiting and purgative abuse suggested an unfavourable prognosis[31].

Patients with restrictive subtypes of ED are known to tend to underestimate the impact of their illness on their everyday activities and often continue to work and to maintain an active lifestyle, even at extreme levels of starvation[32]. There is some evidence that individuals with bingeing and/or purging forms of AN are more impaired than those with restrictive AN[30,33]. Several authors have suggested that restrictive EDs are often experienced as ego-syntonic as a result of the highly valued weight loss associated with these disorders[30,34,35]. In the study by DeJong et al[30], there were no differences in the CIA scores of different diagnostic groups (AN, BN, EDNOS). However when the groups were divided into restrictive and binge-purge subtypes, significant differences were found, as in this study. This suggests a greater degree of functional impairment amongst binge-purge spectrum diagnoses. This is consistent with an apparently higher degree of clinical severity amongst binge-purge spectrum groups than restrictive groups[30]. As Fairburn et al[2] have suggested, is that EDs are not stable. As Fairburn et al[36] one possible explanation note, the current arrangement used for classifying EDs is a historical accident that poorly reflects the clinical reality. They propose a (transdiagnostic) model highlighting similarities amongst diagnoses rather than focusing on differences between EDs[36]. Such similarities include extreme dietary restraint and restriction, binge eating, self-induced vomiting and misuse of laxatives, driven exercising, body checking and avoidance, and an over-evaluation of control over eating, shape and weight[37,38].

In DSM-5 the subtypes of BN disappear, since in clinical practice, the non-purging subtype was uncommon and tended to be confused with the diagnosis of binge ED[39]. Although it is important to clarify that fasting and/or excessive exercise are still considered as control behavior in order not to gain weight in BN, so that this type of patients could continue to be diagnosed. The main purpose of the DSM is to be clinically useful, i.e., to improve the assessment and care of individuals with mental disorders[39]. The current focus of the DSM on “clinical utility” may incentivize the use of MCA and CA methods; the groups of ED patients formed after applying this methodology, do so based on common characteristics (sociodemographic, clinical and HRQoL), which may or may not coincide with the clinical diagnosis of each patient (DSM criteria). The data of this study may have important implications for ED patient care. The development of compensating behaviour-oriented treatments may prove useful for management of ED patients. But before these findings can be used to justify adjustments in therapeutic interventions, they will have to be replicated using the DSM-5 criteria to examine whether similar, or different clusters are present in different populations. Furthermore, future studies are needed to evaluate our ability to use this CA prospectively to classify disease severity and improve ED control by personalizing ED management. It would be interesting to determine whether the cluster groups have a differential response to one or more specific ED treatments. The potential interest in clinical practice is the usefulness that this method can have for clinicians, detecting typologies that may be useful for decision-making in these types of patients.

This study has several strengths. The MCA sought to identify groups of patients with homogeneous characteristics. For quality of life, the MCA methodology shows groups that are more discriminating, i.e., patients of each group (A, B, C, D) are more similar/homogeneous among themselves and dissimilar/heterogeneous among the different groups. This methodology has proven useful for eliminating superfluous variables and retaining significant ones[10]. Traditional statistical methods, such as regression models, are designed to test the relationship between explanatory or independent variables and one outcome or dependent variable. In contrast, the aim in this study was to create ED patient typologies that were not strictly related to a specific outcome. The utility of this approach lies in the fact that the classification does not depend on a specific outcome, but is instead related to several[10]. Appropriate validation of the subtypes identified was provided by statistically significant relationships between the subtypes and several key outcomes.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to apply MCA to ED diagnostic data and to use CA in such detail to search for ED patient groups in this area. Based on a review of the existing literature, only one study[40] used MCA in ED patients, but only in AN patients, and for another purpose (the aim was to differentiate patients with AN into well-defined outcome groups according to specific clusters of prognostic factors).

This study has a number of limitations. The first of these is that it only included patients who were attending a dedicated ED outpatient care program. It may therefore not necessarily be possible to extrapolate the results to other settings, such as inpatients or patients treated as part of primary care. Another limitation is the large number of non-completors, and that there were no analyses of those patients who did and did not participate to determine if they differ based on certain characteristics. The third limitation is that this research was conducted prior to the publication of the DSM-5, and thus used DSM-IV-TR criteria for ED. An examination of patient subtypes across a range of ED patients using the new DSM-5 criteria, will be helpful.

In conclusion, four subtypes of ED patients were identified, which were associated with different illustrative variables. The classification was primarily driven by two components: (1) The HRQoL status; and (2) The sociodemographic data. As Fairburn et al[37] have noted, a classificatory scheme that reflects the clinical reality would greatly facilitate research and clinical practice.

Eating disorders (ED) pose special problems for patients and have serious implications, including impaired health, psychiatric comorbidity and poor quality of life. Some authors assert that there is heterogeneity in clinical presentations that characterize patients with ED. It is relevant to research subtypes of ED, and these groupings might possibly be used to inform assessment, treatment and future diagnostic nosologies.

This is the first study to apply multiple correspondence analysis to EDs diagnostic data and to use cluster analysis (CA) in such detail to search for EDs patient groups in this area.

The aim of our study was to characterize groups of patients with ED into subtypes according to sociodemographic and psychosocial impairment data using multiple correspondence analysis (MCA), and to validate the results using several illustrative variables and arrive at a classification of the subjects that is suggested by the data, rather being defined a priori, where subjects in each group are similar to one another but dissimilar to those from other groups.

This study involved ED patients, who were receiving psychiatric care at the Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo in Biscay, Spain, all of whom were informed of the nature of this research by their psychiatrist before agreeing to participate. MCA provides descriptive patterns based on categories of the original variables, and CA organizes information from apparently heterogeneous individuals into relatively homogeneous groups based on their values in different variables.

Of 176 ED patients were differentiated into well-defined outcome groups according to specific clusters of compensating behaviours. Types D and A were similar with respect to sociodemographic data, while types D and B were similar with respect to psychosocial impairment variables. Types B and D had the least severe ED (according to psychosocial impairment variables); Types A and C had the most severe.

In our study, the MCA methodology shows groups that are more discriminating, i.e., patients of each group (A, B, C, D) are more similar or homogeneous among themselves and dissimilar or heterogeneous among the different groups. A technique such as MCA synthesizes information on the original variables into a small number of components, making data interpretation easier and more viable.

Grouping ED patients into subtypes could help improve the establishment of more effective diagnostic and treatment strategies, and improve patient care and prognosis in clinical practice.

We thank the Research Committee of Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital for help in editing this article. We are most grateful to the individuals with an eating disorder who collaborated with us in our research.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Official Academy of Psychologists, No. BI02843.

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Crenn PP S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Bohn K, O'Connor ME, Doll HA, Palmer RL. The severity and status of eating disorder NOS: implications for DSM-V. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1705-1715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. Therapist competence, therapy quality, and therapist training. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:373-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Davison KM, Marshall-Fabien GL, Gondara L. Sex differences and eating disorder risk among psychiatric conditions, compulsive behaviors and substance use in a screened Canadian national sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:411-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Barajas Iglesias B, Jáuregui Lobera I, Laporta Herrero I, Santed Germán MÁ. Eating disorders during the adolescence: personality characteristics associated with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Nutr Hosp. 2017;34:1178-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2010: 553-564. |

| 6. | Turner H, Tatham M, Lant M, Mountford VA, Waller G. Clinicians' concerns about delivering cognitive-behavioural therapy for eating disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2014;57:38-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mond JM. Classification of bulimic-type eating disorders: from DSM-IV to DSM-5. J Eat Disord. 2013;1:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mond JJ, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Mitchell J. Correlates of the use of purging and non-purging methods of weight control in a community sample of women. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:136-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Turner BJ, Claes L, Wilderjans TF, Pauwels E, Dierckx E, Chapman AL, Schoevaerts K. Personality profiles in Eating Disorders: further evidence of the clinical utility of examining subtypes based on temperament. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arostegui I, Esteban C, García-Gutierrez S, Bare M, Fernández-de-Larrea N, Briones E, Quintana JM; IRYSS-COPD Group. Subtypes of patients experiencing exacerbations of COPD and associations with outcomes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Altobelli E, Rapacchietta L, Marziliano C, Campagna G, Profeta VF, Fagnano R. Differences in colorectal cancer surveillance epidemiology and screening in the WHO European Region. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:2531-2542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sendín-Hernández MP, Ávila-Zarza C, Sanz C, García-Sánchez A, Marcos-Vadillo E, Muñoz-Bellido FJ, Laffond E, Domingo C, Isidoro-García M, Dávila I. Cluster Analysis Identifies 3 Phenotypes within Allergic Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6: 955-961. e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bohn K, Doll HA, Cooper Z, O'Connor M, Palmer RL, Fairburn CG. The measurement of impairment due to eating disorder psychopathology. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:1105-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bohn K, Fairburn CG. Clinical impairment assessment questionnaire (CIA 3.0). Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders. New York: The Guilford Press, 2008: 315-317. |

| 15. | Martín J, Padierna A, Unzurrunzaga A, González N, Berjano B, Quintana JM. Adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the Clinical Impairment Assessment Questionnaire. Appetite. 2015;91:20-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lavik NJ, Clausen SE, Pedersen W. Eating behaviour, drug use, psychopathology and parental bonding in adolescents in Norway. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:387-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wichstrøm L, Skogen K, Øia T. Social and cultural factors related to eating problems among adolescents in Norway. J Adolesc. 1994;17:471. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wichstrøm L. Social, psychological and physical correlates of eating problems. A study of the general adolescent population in Norway. Psychol Med. 1995;25:567-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Las Hayas C, Quintana JM, Padierna JA, Bilbao A, Muñoz P. Use of Rasch methodology to develop a short version of the health related quality of life for eating disorders questionnaire: a prospective study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Engel SG, Adair CE, Las Hayas C, Abraham S. Health-related quality of life and eating disorders: a review and update. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:179-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wells A, Cartwright-Hatton S. A short form of the metacognitions questionnaire: properties of the MCQ-30. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:385-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 696] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Martín J, Padierna A, Unzurrunzaga A, González N, Berjano B, Quintana JM. Adaptation and validation of the Metacognition Questionnaire (MCQ-30) in Spanish clinical and nonclinical samples. J Affect Disord. 2014;167:228-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:487-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3105] [Cited by in RCA: 3182] [Article Influence: 90.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nuevo R, Montorio I, Ruiz MA. Application of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) to elderly population. Ansiedad y Estrés. 2002;8:157-172. |

| 25. | Fresco DM, Heimberg RG, Mennin DS, Turk CL. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:313-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sandín B, Chorot P, Valiente R, Lostao L. Spanish validation of the PSWQ: Factor structure and psychometric properties. Rev Psicopatol Psicol Clín. 2009;14:107-122. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ward JH. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J Am Stat Assoc. 1963;58:236-244. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9993] [Cited by in RCA: 5399] [Article Influence: 87.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Winkler LA, Christiansen E, Lichtenstein MB, Hansen NB, Bilenberg N, Støving RK. Quality of life in eating disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | de la Rie SM, Noordenbos G, van Furth EF. Quality of life and eating disorders. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1511-1522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | DeJong H, Oldershaw A, Sternheim L, Samarawickrema N, Kenyon MD, Broadbent H, Lavender A, Startup H, Treasure J, Schmidt U. Quality of life in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not-otherwise-specified. J Eat Disord. 2013;1:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Steinhausen HC. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1284-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1139] [Cited by in RCA: 999] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Moser CM, Lobato MI, Rosa AR, Thomé E, Ribar J, Primo L, Santos AC, Brunstein MG. Impairment in psychosocial functioning in patients with different subtypes of eating disorders. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2013;35:111-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Mond J, Rodgers B, Hay P, Korten A, Owen C, Beumont P. Disability associated with community cases of commonly occurring eating disorders. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28:246-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ. Assessing quality of life in eating disorder patients. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:171-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Williams S, Reid M. Understanding the experience of ambivalence in anorexia nervosa: the maintainer's perspective. Psychol Health. 2010;25:551-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome "not otherwise specified" (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:691-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fairburn CG, Harrison PJ. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2003;361:407-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1101] [Cited by in RCA: 938] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Herzog DB, Keller MB, Sacks NR, Yeh CJ, Lavori PW. Psychiatric comorbidity in treatment-seeking anorexics and bulimics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:810-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | van Hoeken D, Veling W, Sinke S, Mitchell JE, Hoek HW. The validity and utility of subtyping bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:595-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Errichiello L, Iodice D, Bruzzese D, Gherghi M, Senatore I. Prognostic factors and outcome in anorexia nervosa: a follow-up study. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;21:73-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |