Published online Dec 19, 2021. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i12.1314

Peer-review started: May 23, 2021

First decision: July 14, 2021

Revised: July 18, 2021

Accepted: November 3, 2021

Article in press: November 3, 2021

Published online: December 19, 2021

Processing time: 206 Days and 0.7 Hours

Although the number of senior citizens living alone is increasing, only a few studies have identified factors related to the depression characteristics of senior citizens living alone by using epidemiological survey data that can represent a population group.

To evaluate prediction performance by building models for predicting the depression of senior citizens living alone that included subjective social isolation and perceived social support as well as personal characteristics such as age and drinking.

This study analyzed 1558 senior citizens (695 males and 863 females) who were 60 years or older and completed an epidemiological survey representing the South Korean population. Depression, an outcome variable, was measured using the short form of the Korean version CES-D (short form of CES-D).

The prevalence of depression among the senior citizens living alone was 7.7%. The results of multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the experience of suicidal urge over the past year, subjective satisfaction with help from neighbors, subjective loneliness, age, and self-esteem were significantly related to the depre

It is necessary to strengthen the social network of senior citizens living alone with friends and neighbors based on the results of this study to protect them from depression.

Core Tip: In this study, the significant predictors of depression of the senior citizens living alone were the experiences of suicidal urge over the past year, dissatisfaction with help from neighbors, subjective loneliness, age, and low self-esteem. The results of this study implied that it is necessary to develop a support system customized for subjects to strengthen the relation network for preventing depression in senior citizens living alone so that they can receive actual support (reinforced qualitative network) from acquaintances such as neighbors rather than the frequency of physical contact (reinforced quantitative network).

- Citation: Byeon H. Developing a nomogram for predicting the depression of senior citizens living alone while focusing on perceived social support. World J Psychiatr 2021; 11(12): 1314-1327

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v11/i12/1314.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v11.i12.1314

The incidence of diseases involving senile dementia is rapidly increasing globally due to a rapid increase in the aging population[1]. One of the outcomes of these diseases, depression, is an important and frequent psychiatric disorder in the senile stage, and it is predicted to become the second most important factor in the global disease burden[1]. Since depression can be treated through drug and psychosocial therapy, it is very important to diagnose and treat it as soon as possible. Nevertheless, it is difficult to diagnose depression in the senile stage in good time because it is often erroneously confused with physical symptoms (e.g., a headache, dizziness, etc.) by other family members (senior citizens complain about these more often than younger people), while cognitive decline due to depression is often obscured by the normal aging process[2,3]. Thus, it tends to be neglected without receiving appropriate attention, diagnosis, and/or treatment[2,3]. Hence, many senior citizens living in the community may be suffering from depression even if they have not been clinically diagnosed with it by medical personnel[4].

Although detecting depression in good time is an important requirement for the aged, depression tends to be discovered late or not treated adequately due to various reasons, such as a lack of awareness of one's depression, the complex manifestation of depression, and a decrease in the interest of close acquaintances and family members. However, if geriatric depression is neglected without being properly treated, the individual will suffer from unnecessary mental and social pain, which can lead to serious outcomes such as suicidal ideation[5,6]. Consequently, it is very important to accurately diagnose and detect geriatric depression when treating diseases involving senility[5,6].

The proportion of the elderly population who are living with and/or supported by their children continues to decrease in South Korea in concert with a rapid increase in the number of elderly people living alone[7]. As of 2015, the number of senior citizens living alone in South Korea was 1379000, which is a 1.8-fold increase (777000 people) compared to 2005[7], and is expected to increase to 3.43 million by 2035[7]. Moreover, the proportion of senior citizens living alone is expected to increase to 23.2% in 2035 from 17.8% in 2020. Senior citizens living alone must handle everything that arises in their daily lives, and they exist in poorer environments than those supported by their children not only from economic (income and consumption) and welfare perspectives but also concerning their mental health. The findings from the Survey of Living Con

Although the number of senior citizens living alone is increasing, few researchers have identified factors related to the characteristics of depression in these individuals by using epidemiological survey data representative of this population group. Al

This study is a secondary data based on the Korean Psychosocial Anxiety (KPA) survey, an epidemiological survey representing the South Korean population. KPA-survey was conducted from August to September 2015 by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. The study stratified the population, obtained from the Residence Registration Data (complete enumeration) conducted by the Ministry of Security and Public Administration as of June 2015, into 17 cities and provinces (i.e., Seoul, Busan, Daegu, Incheon, Gwangju, Daejeon, Ulsan, Sejong, Gyeonggi-do, Gangwon-do, Chungcheongbuk-do, Chungcheongnam-do, Jeollabuk-do, Jeollanam-do, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Gyeongsangnam-do, and Jeju-do). Afterward, this study extracted samples using the quota sampling method with considering the gender, age, and residential area ratios. This study selected 200 eups, myeons, and dongs from 3552 eups, myeons, and dongs in South Korea using the probabilities proportional to size (PPS) method. In order to secure randomness when extracting sampling sites, the PPS was applied after sorting the districts in the order of city, county, and district based on the administrative district code. After selecting 200 sampling sites, the 5th household from the Community Service Center of each selected eup, myeon, or dong was chosen as the sampling household by visiting the selected sampling site, and finally, 7000 adults (19 years or older) were surveyed. This study conducted an in-person survey by having trained surveyors who received survey training visit the sample households using the computer assisted personal interview method. This study was approved by H University's Clinical Research Ethics Committee (No. 20180042). This study analy

Depression, an outcome variable, was measured using the short form of the Korean version CES-D (short form of CES-D)[16]. CES-D[15] is a standardized self-report depression test that is used most commonly in the world and can measure depression in healthy people easily. This test was developed by the National Institute of Mental Health for investigating the epidemiological status of depression in a community and has been widely used in many countries in various languages as a screening instru

Explanatory variables were age (continuous variable), alcohol consumption (abstainers or normal drinkers, high-risk drinkers, and those with alcohol use dis

The general characteristics and depression prevalence of the subjects were presented/ present in percentages. The effects of depression were examined by Chi-square test. This study built a depression prediction model using logistic regression analysis to find out the effect of each variable on depression. This study selected variables using step-forward regression analysis. Moreover, this study presented an unadjusted crude model, which was not adjusted with confounding factors, and an adjusted model, which was adjusted with confounding factors.

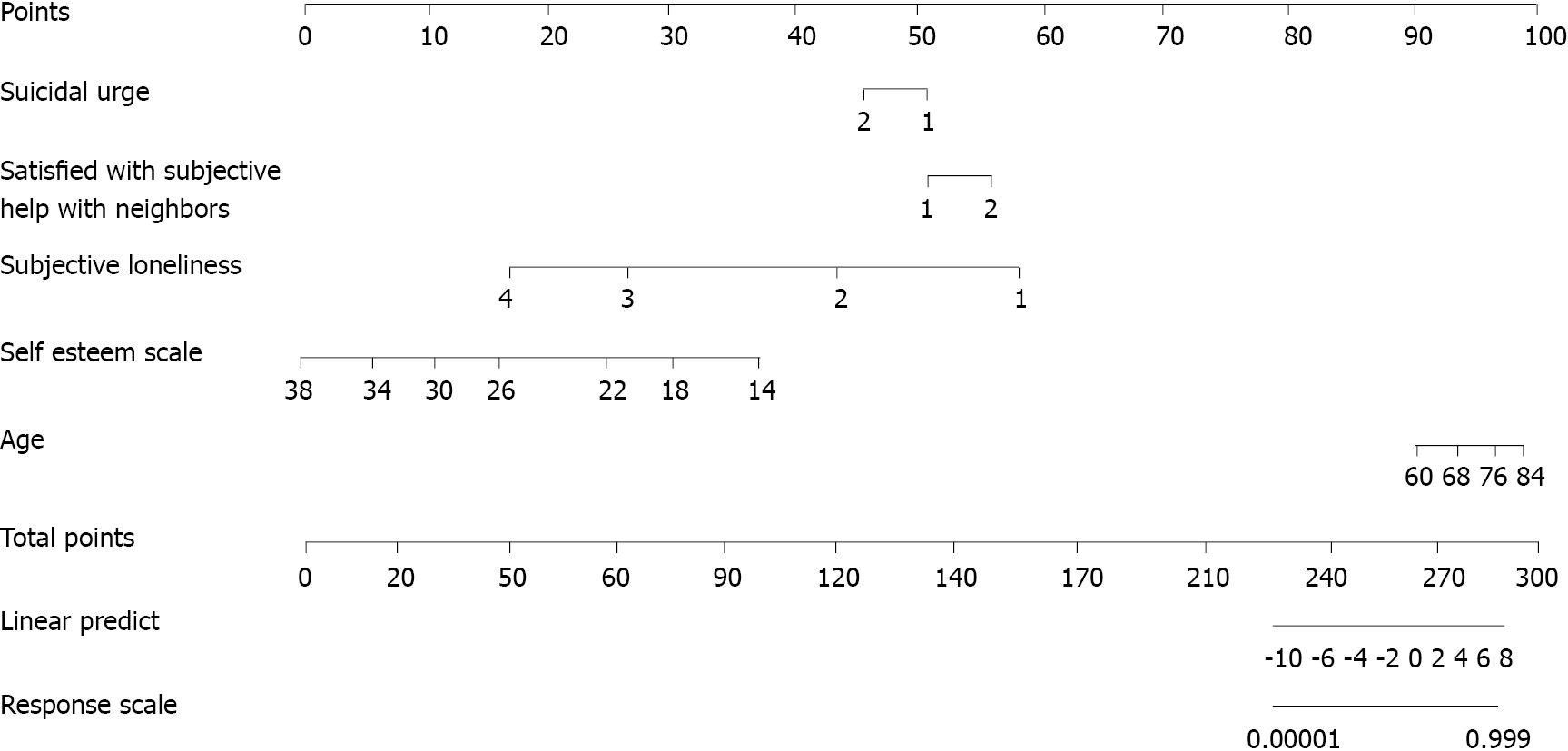

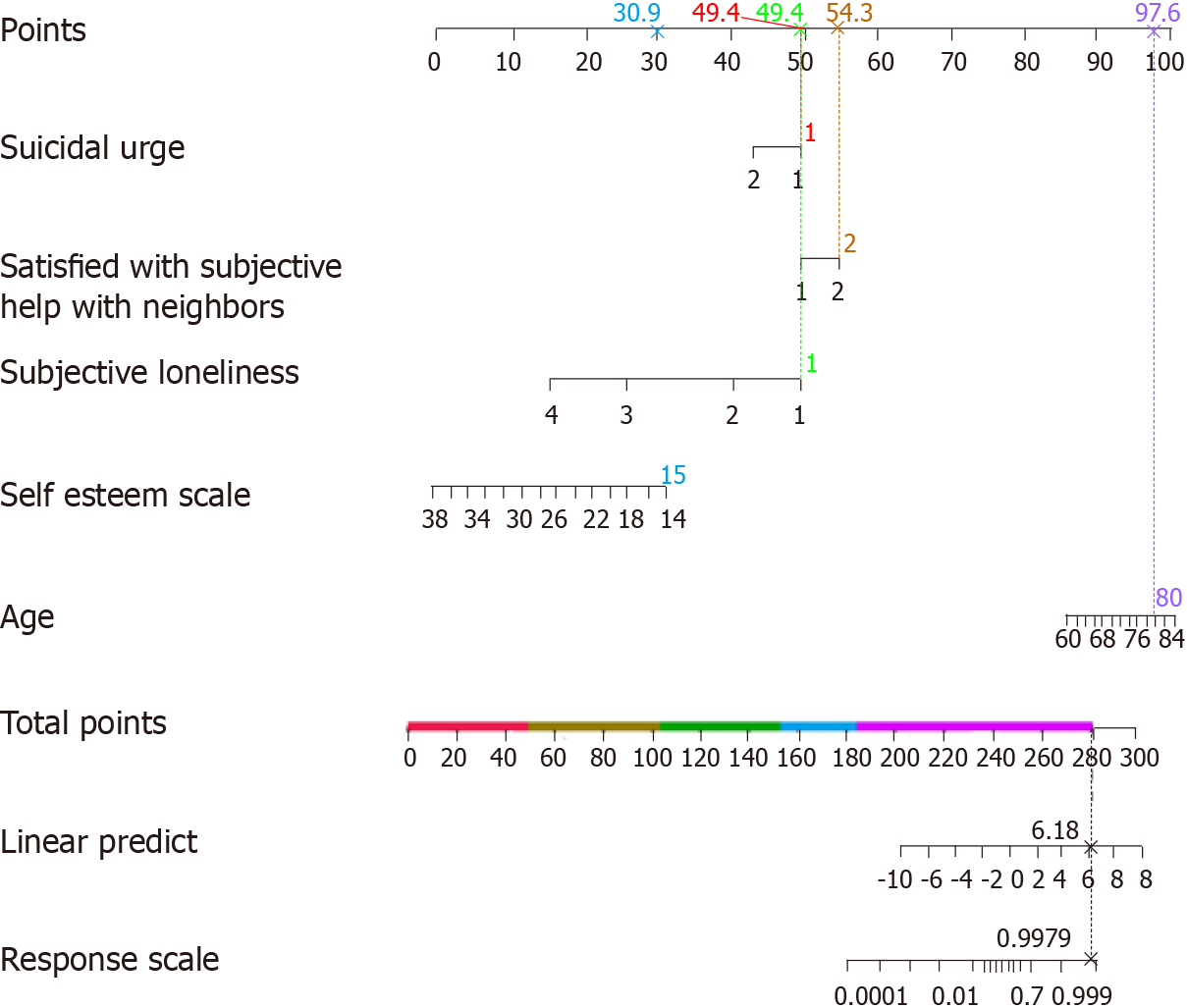

The developed depression prediction model contained a nomogram to make it possible for clinicians to interpret the prediction results (prediction probability) easily. The nomogram was composed of 4 elements. The first was a point line. It was the line located at the top of the monogram to indicate the score corresponding to the risk range of a factor. In the case of a logistic nomogram, it ranged from 0 to 100 points. The second was a risk factor line. This line indicates the score range of a risk factor influencing the occurrence of an event. The number of risk factor lines was equal to the number of risk factors. The third was a probability line. The probability line was the sum of finally calculated nomogram scores and it was placed at the bottom of the nomogram to derive the probability (risk) of depression. The fourth is a total point line. It was constructed by calculating it based on a statistical model.

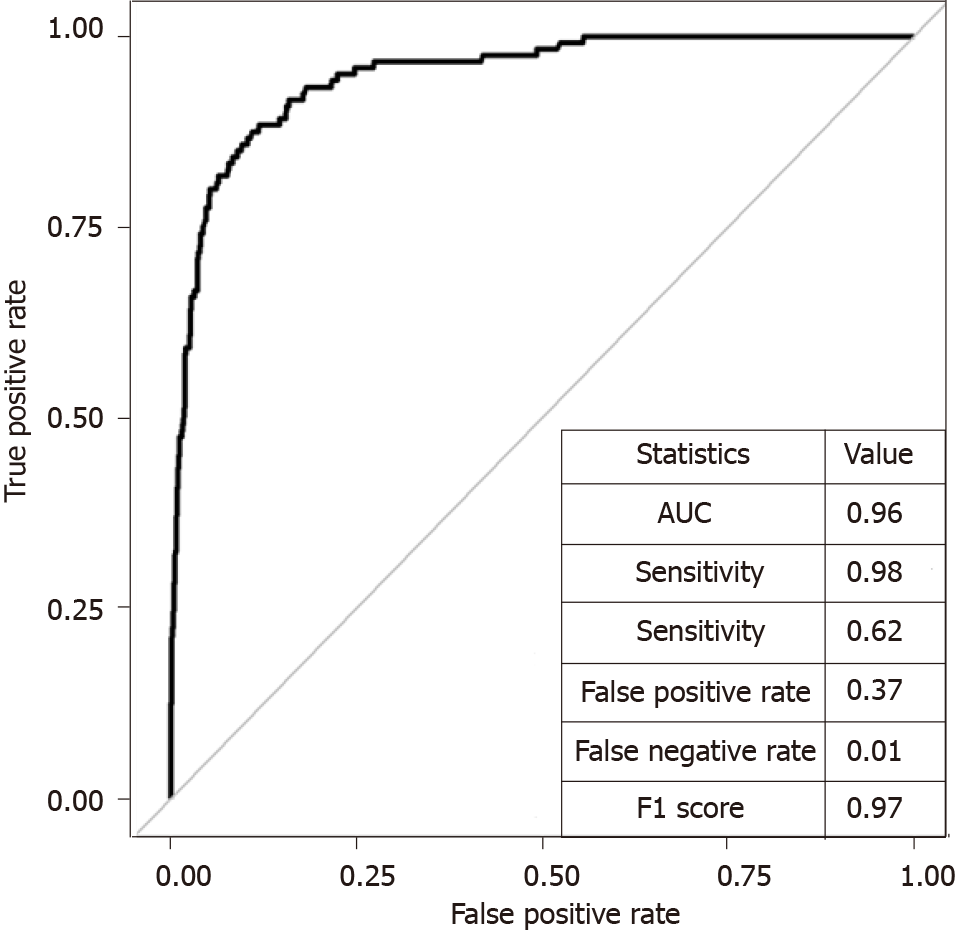

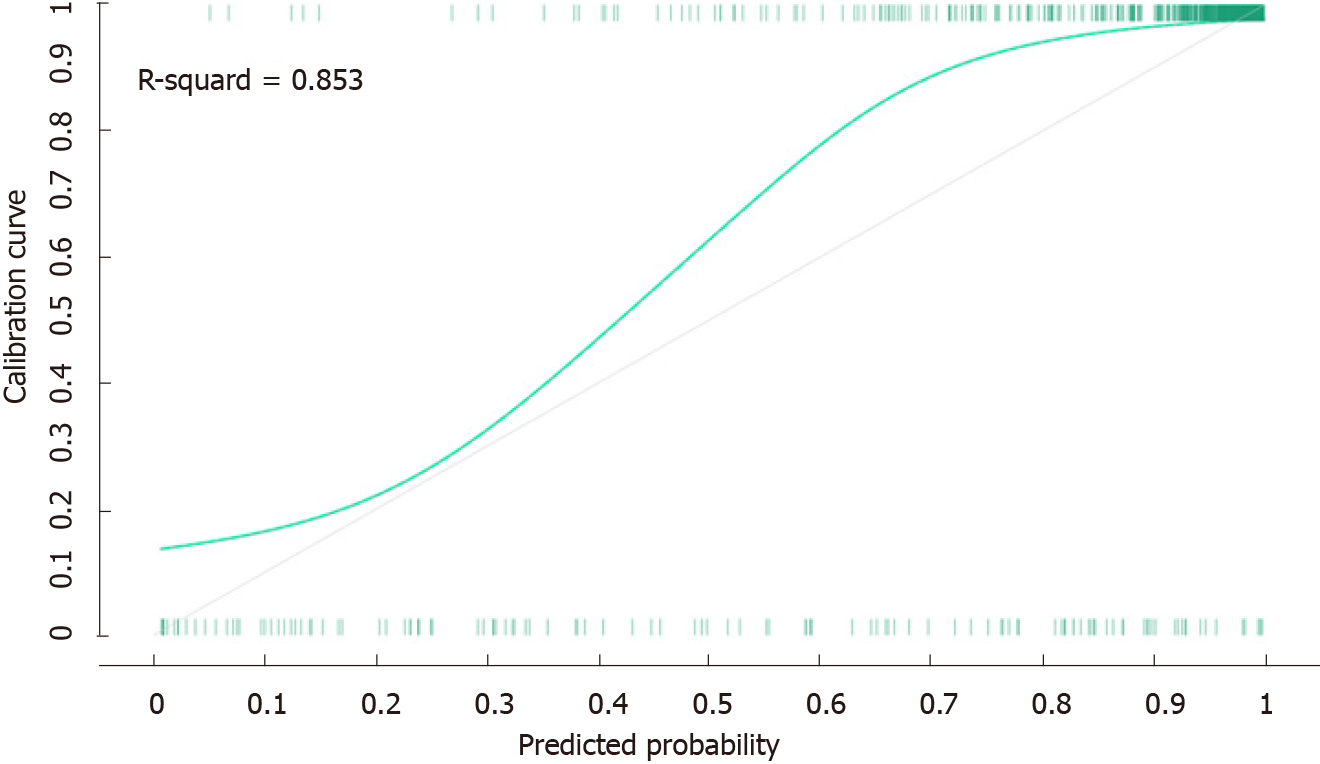

The sample size of this study was small (n = 1558). Therefore, when the prediction performance of the model is validated using a held-out validation method (i.e., a validation method that divides the dataset into a training dataset and a validation dataset at a 7:3 ratio), it poses a risk of overfitting. Consequently, it is more likely to decrease the reliability of prediction results. As a result, this study used 10-fold cross-validation to validate the prediction performance of the developed depression prediction model (nomogram). AUC, general accuracy, balanced accuracy, F1 score, sensitivity, specificity and calibration plot were presented. The calibration plot is a graph for visually confirming the degree of agreement (y, Calibration curve and x, predicted probability) between the predicted probability and the observed probability. Sensitivity indicates the ratio of true positives: The ratio of the developed model to predict the senior citizen living alone with depression as depression. Specificity indicates the ratio of true negatives: The ratio of the developed model to predict the senior citizen living alone without depression as no-depression accurately. R version 4.0.3 (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for analyses and significance level was 0.05 in two-tailed test.

General characteristics of all subjects (1558 subjects) are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 67.9 ± 5.5 years old: 55.4% of them were women and 44.6% of them were men. The results of the AUDIT showed that most of the subjects were normal (52.4%), no suicidal urge over the past one year (91.0%), very rare subjective loneliness (44.1%), and homemaker (35.5%). The prevalence of depression among the senior citizens living alone in the community, measured by short form of CES-D was 7.7%.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 67.9 ± 5.5 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 695 (44.6) |

| Female | 863 (55.4) |

| Occupation (ISCO) | |

| Managers | 20 (1.3) |

| Professional | 12 (0.8) |

| Clerical support workers | 6 (0.4) |

| Service workers | 97 (6.2) |

| Sales workers | 166 (10.7) |

| Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers | 88 (5.6) |

| Craft and related trades workers | 77 (4.9) |

| Plant and machine operators, and assemblers | 9 (0.6) |

| Elementary occupations | 130 (8.3) |

| Housewives | 553 (35.5) |

| Unemployed persons | 399 (25.6) |

| Alcohol use disorder (AUDIT) | |

| Normal drinker | 817 (52.4) |

| High-risk drinker | 278 (17.8) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 13 (0.8) |

| Self-esteem, the experience of suicidal urge over the past year | |

| No | 1418 (91.0) |

| Yes | 140 (9.0) |

| Subjective loneliness | |

| Very rare | 687 (44.1) |

| Occasionally lonely | 639 (41.0) |

| Often lonely | 210 (13.5) |

| Mostly lonely | 22 (1.4) |

| Self-esteem scale, mean ± SD | 28.7 ± 3.4 |

| Depression | |

| No | 1438 (92.3) |

| Yes | 120 (7.7) |

The characteristics of the subjects according to the prevalence of depression are presented in Table 2. The results of chi-square test showed that depression was significantly (P < 0.05) affected by age, self-esteem, subjective frequency of commu

| Variables | Depression | P | |

| No (n = 1438) | Yes (n = 120) | ||

| Age, mean ± SD | 67.75 ± 5.53 | 70.95 ± 4.99 | < 0.0001 |

| Self-esteem scale, mean ± SD | 29.06 ± 3.26 | 25.01 ± 3.43 | < 0.0001 |

| Subjective frequency of communication with other family members, mean ± SD | 2.54 ± 0.95 | 2.05 ± 0.94 | < 0.0001 |

| Subjective frequency of communication with neighbors and friends, mean ± SD | 2.25 ± 1.05 | 2.05 ± 1.11 | 0.05 |

| Alcohol use disorder | < 0.001 | ||

| Normal drinker | 766 (93.8) | 51 (6.2) | |

| High-risk drinker | 258 (92.8) | 20 (7.2) | |

| Alcohol use disorder | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.8) | |

| Self-esteem, the experience of suicidal urge over the past year | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 1349 (95.1) | 69 (4.9) | |

| Yes | 89 (63.6) | 51 (36.4) | |

| Subjective trust satisfaction with neighbors | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 163 (76.9) | 49 (23.1) | |

| Yes | 1275 (94.7) | 71 (5.3) | |

| Subjective satisfaction with help from neighbors | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 420 (85.7) | 70 (14.3) | |

| Yes | 1018 (95.3) | 50 (4.7) | |

| Subjective satisfaction of the living environment of the neighborhood | 0.08 | ||

| No | 245 (89.7) | 28 (10.3) | |

| Yes | 1193 (92.8) | 92 (7.2) | |

| Subjective satisfaction of the safety level of the neighborhood | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 230 (84.3) | 43 (15.7) | |

| Yes | 1208(94.0) | 77 (6.0) | |

| Subjective satisfaction of the medical service of the region | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 386 (88.5) | 50 (11.5) | |

| Yes | 1,438 (92.3) | 120(7.7) | |

| Regular club activities | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 975 (90.5) | 103(9.5) | |

| Yes | 463 (96.5) | 17(3.5) | |

| Subjective loneliness | < 0.001 | ||

| Very rare | 685 (99.7) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Occasionally lonely | 617 (96.6) | 22 (3.44) | |

| Often lonely | 131 (62.4) | 79(37.6) | |

| Mostly lonely | 5 (22.7) | 17(77.3) | |

Table 3 shows a model for predicting the depression of senior citizens living alone. The results of univariate logistic regression analysis (crude model) showed that all vari

| Variables | Crude model | Adjusted model | VIF |

| Alcohol use disorder | |||

| Normal drinker | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| High-risk drinker | 1.16 (0.68, 1.99) | 1.08 (0.45, 2.59) | 1.14 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 17.52 (5.67, 54.06)a | 1.54 (0.16, 14.80) | 1.20 |

| Self-esteem, the experience of suicidal urge over the past year | |||

| No (Ref) | |||

| Yes | 12.83 (7.74, 21.26)a | 3.57 (1.55, 8.22)a | 1.27 |

| Subjective trust satisfaction with neighbors | |||

| No (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.20 (0.12, 0.32)a | 1.02 (0.43, 2.40) | 1.37 |

| Subjective satisfaction with help from neighbors | |||

| No (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.24 (0.15, 0.39)a | 0.29 (0.13, 0.66)a | 1.40 |

| Subjective satisfaction of the living environment of the neighborhood | |||

| No (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.41 (0.25, 0.66)a | 0.51 (0.23, 1.10) | 1.19 |

| Subjective satisfaction of the safety level of the neighborhood | |||

| No (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.32 (0.20, 0.53)a | 0.46 (0.21, 1.04) | 1.19 |

| Subjective satisfaction of the medical service of the region | |||

| No (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.46 (0.28, 0.73)a | 0.56 (0.26, 1.20) | 1.19 |

| Regular club activities | |||

| No (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.38 (0.20, 0.70)a | 2.04 (0.81, 5.15) | 1.31 |

| Subjective loneliness | |||

| Very rare (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Occasionally lonely | 12.21 (2.86, 52.14)a | 5.04 (0.58, 43.39) | 6.87 |

| Often lonely | 206.54 (50.13, 850.86)a | 187.19 (23.17, 1512.13)a | 7.89 |

| Mostly lonely | 1164.50 (210.83, 6431.88)a | 758.12 (56.44, 10183.32)a | 3.10 |

| Subjective frequency of communication with other family members | 0.55 (0.49, 0.61)a | 0.95 (0.71, 1.27) | 2.16 |

| Subjective frequency of communication with neighbors and friends | 0.59 (0.53, 0.66)a | 1.10 (0.81, 1.48) | 2.12 |

| Age | 0.89 (0.85, 0.93)a | 1.17 (1.07, 1.26)a | 1.42 |

| Self-esteem scale | 0.70 (0.65, 0.74)a | 0.81 (0.72, 0.91)a | 1.33 |

A nomogram for predicting the depression of elderly living alone based on multiple risk factors is presented in Figure 1. Among the risk factors of depression of senior citizens living alone, subjective loneliness had the greatest influence, and the senior citizens living alone who responded that they felt lonely showed the highest risk of depression. For example, the nomogram for predicting depression predicted that the depression risk of senior citizens who had suicidal urge over the past year, were not satisfied with subjective help (support) with neighbors, thought that they were mostly lonely, had 15 points in Rosenburg SES scale (self-esteem), and were 80 years or older was 99.8% (Figure 2).

The developed nomogram for predicting the depression of senior citizens living alone was validated by using AUC, general accuracy, balanced accuracy, F1 score, sen

| Measure | Description | Value |

| TP | 1012 | |

| TN | 49 | |

| FP | 29 | |

| FN | 18 | |

| AUC | 0.96 | |

| Accuracy | (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN) | 0.95 |

| Balanced accuracy | [TP/(TP + FN) + TN/(TN + FP)]/2 | 0.80 |

| Sens | TP/(TP + FN) | 0.98 |

| Spec | TN/(TN + FP) | 0.62 |

| FPR | FP/(TN + FP) | 0.37 |

| FNR | FN/(TP + FN) | 0.01 |

| F1 score | 2/(1/Sens + 1/PPV) | 0.97 |

The prevalence of depression in senior citizens living alone in the community mea

In the present study, the significant predictors of depression in senior citizens living alone were suicidal ideation over the past year, dissatisfaction with help (support) from neighbors, subjective loneliness, age, and low self-esteem. It is known that the prevalence of depression in the elderly increases with age[34,35] and low self-esteem[36,37]. Many studies have reported that old people show a high risk of depression regardless of gender because they are more likely to lose their spouses, become phy

Another finding of this study was that poor perceived social support or a weakened social network (social bonds and meaningful social contact[44]) was identified as a risk factor for depression in senior citizens living alone. A social network is a multidimensional concept that encompasses social relationships and factors such as the frequency of contact with family members, friends, and spouses; the degree of mutual assistance; and satisfaction with social relationships can be used to measure it[45]. Previously, several research groups have also reported that the lack of a social network is a major risk factor for depression in the elderly[41,43], which is in agreement with our results.

It has been reported that the reinforcement of a social network (such as support from acquaintances) can alleviate depression (i.e., it is a preventative factor)[46]. In the case of senior citizens living alone, support from acquaintances such as neighbors can complement a lack of support from immediate family members and/or relatives. Senior citizens living alone and interacting with neighbors on equal terms is consi

In summary, the results of the present study reveal that living alone due to the loss of a spouse and/or breakdown of the family network are more likely to cause emo

We identified factors related to depression in the elderly living alone using representative epidemiologic data and developed a nomogram that can help clinicians visually and conveniently identify the risk factors of depression, including social networks as well as demographic factors, which are the advantages of the study.

The limitations of this study are as follows: (1) We could not identify the severity of depression because we only analyzed the prevalence of depression in senior citizens living alone using a depression screening test, further studies are required to prove the risk factors of depression by identifying the severity of depression based on medical diagnosis; (2) We only used a self-report survey on the social isolation or social network of senior citizens living alone; a self-report survey poses the risk of recall bias, so in future studies, we will mitigate this by using interviews with social workers who regularly visit the homes of the senior citizens living alone and collecting data by using the Internet of Things; and (3) Since this is a cross-sectional study, it is impossible to determine causal relationships between the risk factors for depression in senior citizens living alone, and thus, a longitudinal study should be conducted in the future to achieve this.

The results of the present study imply that it is necessary to develop a support system customized for each senior citizen living along by strengthening his/her relationship network for preventing depression. Actual support from acquaintances such as neighbors (reinforcement of the qualitative aspect of the network) rather than the frequency of physical contact (reinforcement of the quantitative aspect of the network) is key for protecting them from depression. Furthermore, establishing an improved mental health policy that identifies and continually manages groups of senior citizens living alone with a high risk of developing depression based on multiple risk factors is needed.

Senile diseases are rapidly increasing globally due to the rapid aging of the popu

Although the number of senior citizens living alone is increasing, only a few studies have identified factors related to the depression characteristics of senior citizens living alone by using epidemiological survey data that can represent a population group.

This study developed a nomogram that allows physicians to check the multiple risk factors of depression of senior citizens living alone using visual graphs and to calculate the prevalence probability of depression while considering the personal characteristics of a subject based on these results.

This study analyzed 1558 senior citizens (695 males and 863 females) who were 60 years or older. Depression, an outcome variable, was measured using the short form of the Korean version CES-D (short form of CES-D). This study built a depression prediction model using logistic regression analysis to find out the effect of each vari

In this study, the significant predictors of depression of the senior citizens living alone were the experiences of suicidal urge over the past year, dissatisfaction with help (support) from neighbors, subjective loneliness, age, and low self-esteem.

The results of this study implied that it is necessary to develop a support system customized for subjects to strengthen the relation network for preventing depression in senior citizens living alone so that they can receive actual support from acqua

It is needed to establish an improved mental health policy that identifies high de

The authors wish to thank the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs that pro

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wang Z S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJ, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2149] [Cited by in RCA: 2072] [Article Influence: 172.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Haigh EAP, Bogucki OE, Sigmon ST, Blazer DG. Depression Among Older Adults: A 20-Year Update on Five Common Myths and Misconceptions. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26:107-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Gomez GE, Gomez EA. Depression in the elderly. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1993;31:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Byeon H. Development of a depression in Parkinson's disease prediction model using machine learning. World J Psychiatry. 2020;10:234-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Conejero I, Olié E, Courtet P, Calati R. Suicide in older adults: current perspectives. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:691-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Szücs A, Szanto K, Aubry JM, Dombrovski AY. Personality and Suicidal Behavior in Old Age: A Systematic Literature Review. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kyunghee Chung. 2017 national survey of older Koreans. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, Sejong, 2018.. |

| 8. | Pogŏn Sahoe Yŏn'gu. The study of the impact of the family type on the health promoting behavior and physical and mental health of elderly people. Health and Social Welfare Review. 2014;34:400-429. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Jia YH, Ye ZH. Impress of intergenerational emotional support on the depression in non-cohabiting parents. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3407-3418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pilania M, Yadav V, Bairwa M, Behera P, Gupta SD, Khurana H, Mohan V, Baniya G, Poongothai S. Prevalence of depression among the elderly (60 years and above) population in India, 1997-2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Buvneshkumar M, John KR, Logaraj M. A study on prevalence of depression and associated risk factors among elderly in a rural block of Tamil Nadu. Indian J Public Health. 2018;62:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | El-Gilany AH, Elkhawaga GO, Sarraf BB. Depression and its associated factors among elderly: A community-based study in Egypt. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;77:103-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mulat N, Gutema H, Wassie GT. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among elderly people in Womberma District, north-west, Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Newman SC, Shrout PE, Bland RC. The efficiency of two-phase designs in prevalence surveys of mental disorders. Psychol Med. 1990;20:183-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385-401. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Bae JN, Cho MJ. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:297-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Haringsma R, Engels GI, Beekman AT, Spinhoven P. The criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of self-referred elders with depressive symptomatology. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:558-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fountoulakis K, Iacovides A, Kleanthous S, Samolis S, Kaprinis SG, Sitzoglou K, St Kaprinis G, Bech P. Reliability, validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2001;1:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1451] [Cited by in RCA: 1605] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gellis ZD. Assessment of a brief CES-D measure for depression in homebound medically ill older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2010;53:289-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Choi DW, Han KT, Jeon J, Ju YJ, Park EC. Association between family conflict resolution methods and depressive symptoms in South Korea: a longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hoe MS, Park BS, Bae SW. Testing measurement invariance of the 11-item Korean version CES-D scale. Mental Health & Social Work. 2015;43:313-339. |

| 23. | Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701-1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 798] [Cited by in RCA: 882] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Wilson J, Hall LA, Rayens MK, Sachs B, Cunningham LL. Psychometrics for two short forms of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1998;19:481-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cho JH, Olmstead R, Choi H, Carrillo C, Seeman TE, Irwin MR. Associations of objective versus subjective social isolation with sleep disturbance, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23:1130-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rosenberg M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). In Rosenberg M: Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Basic Books, 1979: 61. |

| 27. | Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7971] [Cited by in RCA: 8953] [Article Influence: 279.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Newman SC, Sheldon CT, Bland RC. Prevalence of depression in an elderly community sample: a comparison of GMS-AGECAT and DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1339-1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Slade T, Brownhill S, Andrews G. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV major depression in an Australian national survey. J Affect Disord. 2003;75:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Battaglia A, Dubini A, Mannheimer R, Pancheri P. Depression in the Italian community: epidemiology and socio-economic implications. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:135-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:249-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1380] [Cited by in RCA: 1418] [Article Influence: 64.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ. Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 805] [Cited by in RCA: 670] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Park JH, Kim KW, Kim MH, Kim MD, Kim BJ, Kim SK, Kim JL, Moon SW, Bae JN, Woo JI, Ryu SH, Yoon JC, Lee NJ, Lee DY, Lee DW, Lee SB, Lee JJ, Lee JY, Lee CU, Chang SM, Jhoo JH, Cho MJ. A nationwide survey on the prevalence and risk factors of late life depression in South Korea. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:34-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kok RM, Reynolds CF 3rd. Management of Depression in Older Adults: A Review. JAMA. 2017;317:2114-2122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kim JM, Shin IS, Yoon JS, Stewart R. Prevalence and correlates of late-life depression compared between urban and rural populations in Korea. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:409-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tosangwarn S, Clissett P, Blake H. Predictors of depressive symptoms in older adults living in care homes in Thailand. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32:51-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wang X, Wang W, Xie X, Wang P, Wang Y, Nie J, Lei L. Self-esteem and depression among Chinese adults: a moderated mediation model of relationship satisfaction and positive affect. Pers Individ Dif. 2018;135:121-127. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017;143:783-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1293] [Cited by in RCA: 1423] [Article Influence: 177.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Cao W, Guo C, Ping W, Tan Z, Guo Y, Zheng J. A Community-Based Study of Quality of Life and Depression among Older Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wu HY, Chiou AF. Social media usage, social support, intergenerational relationships, and depressive symptoms among older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2020;41:615-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ge L, Yap CW, Ong R, Heng BH. Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: A population-based study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Yao HM, Xiao RS, Cao PL, Wang XL, Zuo W, Zhang W. Risk factors for depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. World J Psychiatry. 2020;10:59-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Noguchi T, Saito M, Aida J, Cable N, Tsuji T, Koyama S, Ikeda T, Osaka K, Kondo K. Association between social isolation and depression onset among older adults: a cross-national longitudinal study in England and Japan. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e045834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kelly ME, Duff H, Kelly S, McHugh Power JE, Brennan S, Lawlor BA, Loughrey DG. The impact of social activities, social networks, social support and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Krause N. Assessing change in social support during late life. Res Aging. 1999;21:539-569. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Domènech-Abella J, Lara E, Rubio-Valera M, Olaya B, Moneta MV, Rico-Uribe LA, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Mundó J, Haro JM. Loneliness and depression in the elderly: the role of social network. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:381-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |