Published online Dec 19, 2021. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v11.i12.1267

Peer-review started: April 1, 2021

First decision: June 17, 2021

Revised: June 27, 2021

Accepted: September 22, 2021

Article in press: September 22, 2021

Published online: December 19, 2021

Processing time: 249 Days and 9.8 Hours

The corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in most nations deciding upon self-isolation and social distancing policies for their citizens to control the pandemic and reduce hospital admission. This review aimed at evaluating the effect of physical activity on mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic may lead to augmented levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-2 that led to cardiovascular and neurological disorders associated with highly inflammatory effects of viral infection affecting the brain tissues leading to damage of the nervous system and resulting in cognition dysfunction, insulin sensitivity reduction, and behavioral impairments. Anxiety and depression may lead to negative effects on various quality of life domains, such as being physically inactive. Regular physical activities may reduce inflammatory responses, improve ACE-2 responses, and improve mental well-being during self-isolation and social distancing policies related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Further studies should be conducted to assess the different intensities of physical activities on cardiova

Core Tip: The corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in most nations deciding upon self-isolation and social distancing policies for their citizens to control the pandemic and reduce hospital admission. This review aimed at evaluating the effect of physical activity on mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 may lead to cardiovascular and neurological disorders associated with inflammatory effects of viral infection affecting brain tissues, leading to nervous system damage and cognitive dysfunction, insulin sensitivity reduction, and behavioral impairments. Regular physical activities may reduce inflammatory responses, improve angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 responses, and mental well-being during self-isolation and social distancing.

- Citation: Abdelbasset WK, Nambi G, Eid MM, Elkholi SM. Physical activity and mental well-being during COVID-19 pandemic. World J Psychiatr 2021; 11(12): 1267-1273

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v11/i12/1267.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v11.i12.1267

The corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 appeared in China in 2019[1]. The infection probably resulted from a usual assortment of animal hosts prior to zoonotic spread that affected populations worldwide and caused thousands of deaths[2]. Through a cellular membrane receptor known as angiotensin-converting enzyme-2, SARS-COV-2 influences host cells, affects lungs with insufficient oxygen supply, and accordingly may affect cardiac and brain tissues[3]. With the rapid progress of COVID-19, most nations decided upon self-isolation and social distancing policies for their citizens and residents to control the pandemic and reduce hospital admission, with a recommendation of self-isolation and social distancing to successfully control the pandemic outbreak[4].

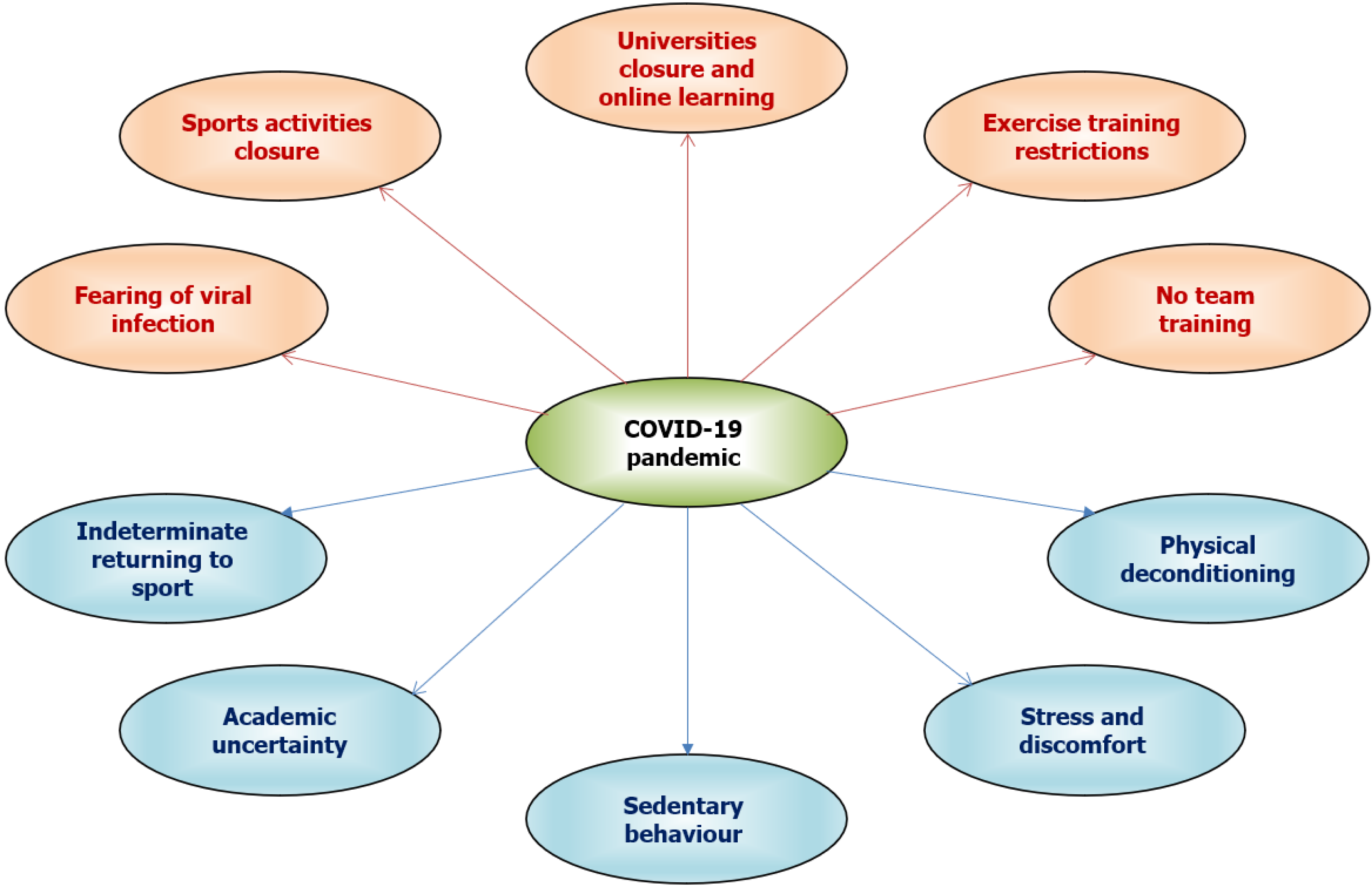

At this time, it is important for all populations to understand the local characteristics of COVID-19 transmission and social distancing policy as the transmission of COVID-19 is predicted to occur up to 2024, and intermittent or extended social distancing may be continued to 2022 and will cause major lifestyle changes among people worldwide[5]. Therefore, it is doubtful during these policies that individuals can continue their sedentary behaviors to maintain their healthy condition[6]. Government policies of social isolation and distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic can increase disturbance of mental health, including anxiety and depression[7]. Figure 1 presents the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and mental health.

Nutritional deprivation may affect cognitive status and lead to mood disorders[8]. Poor physical activity levels during COVID-19 quarantine can also lead to sedentary behaviors that could lead to the development of chronic cardiovascular, metabolic and mood disorders[9,10]. Several studies have reported that regular physical activity and exercise training are considered effective nonpharmacological interventions in several chronic disorders[9].

Generally, the development and prevalence of mental health impairments are associated with social and physical determinants[11]. Community service integration may promote awareness of mental well-being, reduce discrimination and stigma, support social recovery, and prevent mental dysfunction[12,13].

International guidelines accentuate community care for mental well-being and the World Health Organization also has suggested stipulations of integrated and comprehensive social care for mental well-being, including prevention and interventional protocols in the community incorporating the perceptions of families and service providers[14]. It is reported that individuals with psychological impairment should be encouraged to live without assistance among populations[15].

Brain tissues may be affected by viral infection due to infected nerve cells through infected vascular endothelium, or leukocyte migration into the brain circulation[16]. Although headache and anosmia are the major prevalent neurological disorders related to COVID-19, neurophysiological impairments have been documented, including encephalopathy, seizures, consciousness impairment, and stroke[17,18].

It was reported that approximately 36% of COVID-19 patients suffered from neurological symptoms such as impaired consciousness and cerebrovascular disorders associated with inflammatory effects of viral infection[19]. This inflammation may affect the brain tissues leading to damage of the nervous system and cognitive dysfunction, insulin sensitivity reduction, and behavioral impairments[20]. Also, these inflammatory reactions associated with viral infection may develop primitive neurological manifestations[21].

Due to impaired neural plasticity, the initial fatality of nerve cells, and disturbed neurotransmitter production, psychoses, impaired memory, and post-traumatic stress disorders may occur with COVID-19[22]. In addition, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-2 is expressed with COVID-19 in several brain areas, such as the olfactory system, striatum, and cortex, and on various types of nerve cells such as astrocytes, microglia, neurons, and oligodendrocytes[23]. The primary projected mechanism that affects the function of the nervous system is ACE-2 activation associated with COVID-19 through augmentation of inflammatory responses[20,23].

A recent cross-sectional study found that individuals who conducted a regular physical exercise for one month had good life satisfaction during quarantine, while the individuals who stayed at home and without physical exercise suffered from poor health conditions[24]. It was also reported that isolation and social distancing related to COVID-19 led to a greater incidence of anxiety and depression[25]. Accordingly, these reports suggest that individuals who conducted physical exercise during COVID-19 should be regularly observed as they may be particularly irritated by self-isolation. Therefore, exercise training for a long time does not indicate good mental well-being, but it may be a predictor of developing mood disorders[25].

It can be assumed that overtraining or prolonged exercise training may lead to pessimistic health conditions such as mood disorders[20]. The quarantine associated with COVID-19 may increase the development of a sedentary lifestyle among different populations including adolescents[26]. Regular exercise training improves immune function, lowers the severity of symptoms, and reduces the mortality rate in individuals exposed to viral infection[10]. Conducting physical activity or sports during the COVID-19 pandemic may provide a complementary and alternative treatment to develop mental well-being[27].

It is documented that COVID-19 may be associated with neurotropism, neuroinvasion, and neuroinflammation that could clearly affect the outcomes of mental well-being including acute myelitis, cerebrovascular disorders, encephalitis, and encephalopathy[28]. Several exercise training programs and different laboratory investigations should be conducted to assess the influence of exercise training on COVID-19 and how it prevents disturbances of mental well-being. Regrettably, studies that suggest or explain the ideal exercise protocol conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and its influence on mental and cardiovascular well-being are limited, and therefore the relationship between exercise training, cardiovascular function, and mental well-being should be investigated.

Anxiety and depression are the most frequent mental disorders, with varied incidence rates among different ages, including adults, adolescents, children, and particularly aged individuals[29]. It is reported that anxiety and depression may lead to negative effects on various quality of life domains, such as being physically inactive[30]. The pathophysiology of anxiety and depression is still not clearly explained, and an abundance of biomarkers have been recommended to identify the sequences and development of mental disorders[30,31].

Recent studies have proved that adherence to physical activities and exercise training programs during COVID-19 quarantine is associated with better mental health and lower anxiety and depression levels. However, poor physical activity levels are associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression in addition to poor mental health and well-being[32-40] (Table 1).

| Refs | Measures | Findings and recommendations |

| Wright et al[32], 2021 | Incidence of fear, physical activity, and mental well-being indicators questionnaires | Physical activity may improve mental well-being and protect against the undesirable impacts of COVID-19. Regular physical activities should be encouraged to improve mental well-being during COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Xiao et al[33], 2021 | Lifestyle and home environment, physical and mental well-being, and occupational environment questionnaires | Significant reduction in physical and mental well-being including impaired physical activity, increased junk food intake, and absence of coworker communications |

| Faulkner et al[34], 2021 | Short form of IPAQ, WHO-5 well-being index, and depression, anxiety and stress scale-9 | Negative changes in physical activity before COVID-19 containment policies presented poor mental well-being, while positive physical activity behavior showed better mental well-being |

| Meyer et al[35], 2020 | Self-reported physical activity, anxiety and depression status, social connection, loneliness, and stress | Adherence to physical activity contributions and restrictive screening time during unexpected societal alterations may alleviate the consequences of mental well-being |

| Carriedo et al[36], 2020 | International Physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ), 6-item self-report scale of depression symptoms, Connor-Davidson CD-RISC resilience scale, and positive and negative affect schedule | Regular moderate or vigorous physical activity provide positive resilience and reduce depression symptoms during COVID-19 quarantine |

| Maugeri et al[37], 2020 | IPAQ and psychological general well-being index | Reduced physical activity have a greatly undesirable effects on psychological status and mental well-being. Adherence to a regular physical activity program is the main approach for improving physical and mental well-being during COVID-19 confinement. |

| López-Bueno et al[38], 2020 | Short form of physical activity vital sign and single-item question for mood and anxiety | Adherence to regular physical activities associated with better mood and lower anxiety with WHO recommendations during COVID-19 quarantine |

| Duncan et al[39], 2020 | Online survey on perceived changes in physical activity due to COVID-19 mitigation and mental well-being using 10-item perceived stress scale and 6-item anxiety subscale | COVID-19 mitigation policies may affect physical activity and mental well-being. Participants with reduced physical activity levels showed higher anxiety and stress levels. |

| Jacob et al[40], 2020 | Self-reported physical activity questionnaire, Beck anxiety and depression inventories, and 7-item short Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale | During COVID-19 social distancing, participants adherent to vigorous and moderate physical activity showed better mental well-being |

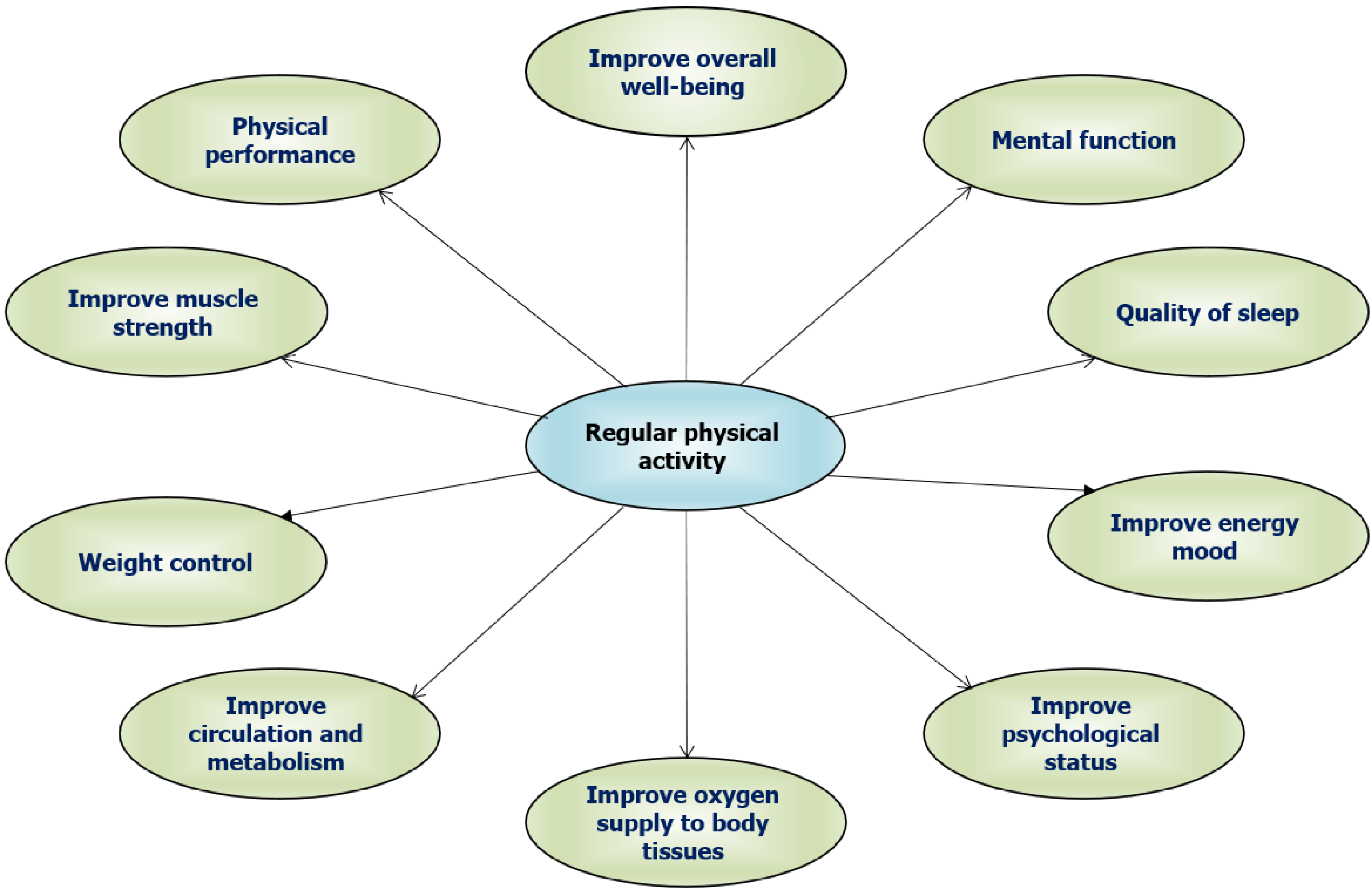

Exercise training and physical activity have been suggested as nonpharmacological interventions to eliminate the complications associated with self-isolation and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic [27]. The effects of different exercise programs are not being clearly investigated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Physical activity may improve mental well-being and protect against the undesirable impacts of COVID-19. Regular physical activities should be encouraged to improve mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic[32-40]. Figure 2 shows the positive effects of regular physical activity on physical and mental well-being.

The COVID-19 pandemic may lead to augmented levels of ACE-2 that led to cardiovascular and neurological disorders associated with inflammatory effects of viral infection, affecting the brain tissues and leading to damage to the nervous system and cognitive dysfunction, insulin sensitivity reduction, and behavioral impairments. Anxiety and depression may lead to negative effects on various quality of life domains, such as being physically inactive. Regular physical activities may reduce inflammatory responses, improve ACE-2 responses and mental well-being during self-isolation and social distancing related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Further studies should be conducted to assess the different intensities of physical activities on cardiovascular function, and mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mukherjee M S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, Tamin A, Harcourt JL, Thornburg NJ, Gerber SI, Lloyd-Smith JO, de Wit E, Munster VJ. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564-1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5894] [Cited by in RCA: 5665] [Article Influence: 1133.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2020;26:450-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3581] [Cited by in RCA: 2866] [Article Influence: 573.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Libby P. The Heart in COVID-19: Primary Target or Secondary Bystander? JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5:537-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kucharski AJ, Klepac P, Conlan AJK, Kissler SM, Tang ML, Fry H, Gog JR, Edmunds WJ; CMMID COVID-19 working group. Effectiveness of isolation, testing, contact tracing, and physical distancing on reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in different settings: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1151-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 622] [Cited by in RCA: 553] [Article Influence: 110.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, Grad YH, Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368:860-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1897] [Cited by in RCA: 1564] [Article Influence: 312.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hall G, Laddu DR, Phillips SA, Lavie CJ, Arena R. A tale of two pandemics: How will COVID-19 and global trends in physical inactivity and sedentary behavior affect one another? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;64:108-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 83.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abdelbasset WK. Stay Home: Role of Physical Exercise Training in Elderly Individuals' Ability to Face the COVID-19 Infection. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:8375096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sousa RAL, Freitas DA, Leite HR. Cross-talk between obesity and central nervous system: role in cognitive function. Interv Obes Diabetes. 2019;3:7-9. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine - evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25 Suppl 3:1-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1405] [Cited by in RCA: 1919] [Article Influence: 213.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abdelbasset WK, Alqahtani BA, Alrawaili SM, Ahmed AS, Elnegamy TE, Ibrahim AA, Soliman GS. Similar effects of low to moderate-intensity exercise program vs moderate-intensity continuous exercise program on depressive disorder in heart failure patients: A 12-week randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sederer LI. The Social Determinants of Mental Health. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67:234-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jorm AF. Mental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am Psychol. 2012;67:231-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 732] [Cited by in RCA: 801] [Article Influence: 57.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Evans-Lacko S, Corker E, Williams P, Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Effect of the Time to Change anti-stigma campaign on trends in mental-illness-related public stigma among the English population in 2003-13: an analysis of survey data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saxena S, Funk M, Chisholm D. WHO's Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020: what can psychiatrists do to facilitate its implementation? World Psychiatry. 2014;13:107-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kohrt BA, Asher L, Bhardwaj A, Fazel M, Jordans MJD, Mutamba BB, Nadkarni A, Pedersen GA, Singla DR, Patel V. The Role of Communities in Mental Health Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Meta-Review of Components and Competencies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis and Neurologic Manifestations of the Coronaviruses in the Age of Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Review. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1018-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 714] [Cited by in RCA: 655] [Article Influence: 131.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vaira LA, Salzano G, Deiana G, De Riu G. Anosmia and Ageusia: Common Findings in COVID-19 Patients. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:1787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 93.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Orozco-Hernández JP, Marin-Medina DS, Sánchez-Duque JA. [Neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection]. Semergen. 2020;46 Suppl 1:106-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X, Li Y, Hu B. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4761] [Cited by in RCA: 4704] [Article Influence: 940.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | De Sousa RAL, Improta-Caria AC, Aras-Júnior R, de Oliveira EM, Soci ÚPR, Cassilhas RC. Physical exercise effects on the brain during COVID-19 pandemic: links between mental and cardiovascular health. Neurol Sci. 2021;42:1325-1334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Karwowski MP, Nelson JM, Staples JE, Fischer M, Fleming-Dutra KE, Villanueva J, Powers AM, Mead P, Honein MA, Moore CA, Rasmussen SA. Zika Virus Disease: A CDC Update for Pediatric Health Care Providers. Pediatrics. 2016;137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Huarcaya-Victoria J, Meneses-Saco A, Luna-Cuadros MA. Psychotic symptoms in COVID-19 infection: A case series from Lima, Peru. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen R, Wang K, Yu J, Howard D, French L, Chen Z, Wen C, Xu Z. The Spatial and Cell-Type Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 in the Human and Mouse Brains. Front Neurol. 2020;11:573095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 78.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang SX, Wang Y, Rauch A, Wei F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 441] [Cited by in RCA: 420] [Article Influence: 84.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pearson GS. The Mental Health Implications of COVID-19. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2020;26:443-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lam K, Lee JH, Cheng P, Ajani Z, Salem MM, Sangha N. Pediatric stroke associated with a sedentary lifestyle during the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic: a case report on a 17-year-old. Neurol Sci. 2021;42:21-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jiménez-Pavón D, Carbonell-Baeza A, Lavie CJ. Physical exercise as therapy to fight against the mental and physical consequences of COVID-19 quarantine: Special focus in older people. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63:386-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 534] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 82.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yachou Y, El Idrissi A, Belapasov V, Ait Benali S. Neuroinvasion, neurotropic, and neuroinflammatory events of SARS-CoV-2: understanding the neurological manifestations in COVID-19 patients. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:2657-2669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: Global Health Estimates. World Health Organization 2017. [cited 20 February 2021]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254610. |

| 30. | Vancini RL, Rayes ABR, Lira CAB, Sarro KJ, Andrade MS. Pilates and aerobic training improve levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in overweight and obese individuals. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017;75:850-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Strawbridge R, Young AH, Cleare AJ. Biomarkers for depression: recent insights, current challenges and future prospects. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1245-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wright LJ, Williams SE, Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJCS. Physical Activity Protects Against the Negative Impact of Coronavirus Fear on Adolescent Mental Health and Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12:580511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Xiao Y, Becerik-Gerber B, Lucas G, Roll SC. Impacts of Working From Home During COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Well-Being of Office Workstation Users. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63:181-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 64.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Faulkner J, O'Brien WJ, McGrane B, Wadsworth D, Batten J, Askew CD, Badenhorst C, Byrd E, Coulter M, Draper N, Elliot C, Fryer S, Hamlin MJ, Jakeman J, Mackintosh KA, McNarry MA, Mitchelmore A, Murphy J, Ryan-Stewart H, Saynor Z, Schaumberg M, Stone K, Stoner L, Stuart B, Lambrick D. Physical activity, mental health and well-being of adults during initial COVID-19 containment strategies: A multi-country cross-sectional analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2021;24:320-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Meyer J, McDowell C, Lansing J, Brower C, Smith L, Tully M, Herring M. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 80.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Carriedo A, Cecchini JA, Fernandez-Rio J, Méndez-Giménez A. COVID-19, Psychological Well-being and Physical Activity Levels in Older Adults During the Nationwide Lockdown in Spain. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:1146-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Maugeri G, Castrogiovanni P, Battaglia G, Pippi R, D'Agata V, Palma A, Di Rosa M, Musumeci G. The impact of physical activity on psychological health during Covid-19 pandemic in Italy. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 513] [Cited by in RCA: 460] [Article Influence: 92.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | López-Bueno R, Calatayud J, Ezzatvar Y, Casajús JA, Smith L, Andersen LL, López-Sánchez GF. Association Between Current Physical Activity and Current Perceived Anxiety and Mood in the Initial Phase of COVID-19 Confinement. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Duncan GE, Avery AR, Seto E, Tsang S. Perceived change in physical activity levels and mental health during COVID-19: Findings among adult twin pairs. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0237695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Jacob L, Tully MA, Barnett Y, Lopez-Sanchez GF, Butler L, Schuch F, López-Bueno R, McDermott D, Firth J, Grabovac I, Yakkundi A, Armstrong N, Young T, Smith L. The relationship between physical activity and mental health in a sample of the UK public: A cross-sectional study during the implementation of COVID-19 social distancing measures. Ment Health Phys Act. 2020;19:100345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |