Peer-review started: October 6, 2015

First decision: October 27, 2015

Revised: November 19, 2015

Accepted: December 13, 2015

Article in press: December 14, 2015

Published online: March 9, 2016

Processing time: 163 Days and 16.2 Hours

Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) drugs are widely prescribed for inflammatory disease. A loss of response to adalimumab is frequent and the pharmacokinetics of anti-TNF therapy have important implications for patient management. Individual factors such as albumin, body weight, and disease severity based on the C-reactive protein level influence drug metabolism. Adalimumab trough levels are associated with clinical remission. On the other hand, the detection of antibodies is associated with clinical relapse. Immunosuppressive therapy could reduce antibody formation although the clinical impact is not proven. New algorithms are available to provide personalized treatment and adapt the dosage. More data are needed on dose de-escalation.

Core tip: We have reviewed all the recent data about the factors that influence Adalimumab pharmacokinetics and the impact for the clinicians in the assessment of inflammatory disease. We looked at the inter patient variability, the drug clearance, antibodies detection, the effect of concomitant use of immunosuppressive.

- Citation: Pelletier AL, Nicaise-Roland P. Adalimumab and pharmacokinetics: Impact on the clinical prescription for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Pharmacol 2016; 5(1): 44-50

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3192/full/v5/i1/44.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5497/wjp.v5.i1.44

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic disease due to immune dysregulation of the commensal enteric flora in genetically susceptible individuals. There is overproduction of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha by monocytes macrophages and T cells[1-3].

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies targeting the tumor necrosis alpha pathway for the treatment of immune disease have been shown to be effective. Adalimumab is a recombinant fully human subcutaneously delivered immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody. It has binding properties and affinities for the soluble and transmembrane form of TNF alpha[4]. Anti-TNF drugs have been approved for use in moderate to severe CD when corticosteroids and/or immunomodulators have failed[5].

Twenty-five percent to 30% of patients show no or limited response to these treatments and treatment becomes ineffective during maintenance therapy in 50% of responders[2,6]. Dose escalation is often necessary to maintain a clinical response[7,8]. In addition, the aim of treatment has changed from sustained corticoid free remission to mucosal healing[9]. Little is known about the exposure - response relationship and the factors affecting it. These factors must be clarified to improve the therapeutic efficacy of these drugs. In addition, the pharmacology of anti-TNF drugs depends on the structure of the antibody as well as the properties of the target antigen[2,10]. All of these data suggest that individualize therapy and dosing are necessary[11].

This review will present the most recent data on the factors influencing Adalimumab pharmacokinetics and their clinical impact in the assessment of inflammatory bowel disease.

Maintaining effective concentrations of anti-TNF drugs is not easy and deciding on the appropriate dose depends mainly on clinical symptoms or biological data. Pharmacokinetic data have recently been shown to help with this decision[2].

There seems to be different types of non-responders with several pathogenic mechanisms causing non-response. It is unclear why certain non-responders to one anti-TNF respond to another one while others require a different drug.

One potential explanation for the lack of response to TNF is incomplete suppression of TNF activity[4]. Suboptimal exposure may be due to underdosing, rapid drug clearance and/or the development of anti-drug antibodies.

The effective dose of each individual must be identified to adjust the doses of anti-TNF during the course of drug absorption. For example, subcutaneous absorption varies among patients due to lymphatic drainage, a smaller volume of the drug than with intravenous administration and the risk of immunogenicity associated with a skin reaction[4]. Subcutaneous absorption is slow, incomplete and variable. It takes between 2 to 8 d to reach maximum plasma concentrations. Fifty percent to 100% of the administered dose is absorbed, depending on age, body weight and injection site[2]. Low albumin as well as high body mass index (BMI) and male sex increase drug clearance as shown with Infliximab[12-14]. Adalimumab concentrations were also negatively associated with C-reaction protein (CRP) and correlated to disease severity (Table 1)[15,16]. Disease type has also been shown to influence drug response because patients with ulcerative colitis seemed to have faster clearance than CD patients. One hypothesis is that the overall inflammatory burden in patients with ulcerative colitis is higher with a greater area of mucosal lesions and a greater loss of medication in the intestinal lumen. These data must be confirmed[4].

| Sub-cutanous absorption | Age/sex |

| Body weight | |

| Injection site | |

| Disease activity | CRP |

| Nutritional condition | Albumin |

While inter-individual levels vary, intra-patient adalimumab levels are relatively stable over time (28 wk of follow-up)[16].

Because of their high molecular weight, monoclonal antibodies do not undergo renal elimination or metabolism by hepatocytes[4,12].

The primary route of IgG clearance is the intracellular proteolytic catabolism via the reticuloendothelial system with receptor mediated endocytosis. This is a saturable route of clearance[2,4].

The drug provokes antibody formation. An inactive drug antibody complex (neutralizing antibody), may result in decreased efficacy. The drug antibody complex can also be cleared, providing an alternative clearance pathway for therapeutic protein[17,18].

Drug and antibody dosing can be performed. In clinical practice, Maser et al[19] first described the correlation between detectable infliximab trough levels and improved clinical outcomes in CD patients. Results were similar for rheumatoid arthritis[20]. Baert et al[21] first reported that patients with anti-infliximab antibodies lost the response to therapy faster than those without. Low infliximab trough levels and high antibodies were significantly more prevalent in patients with a loss of response. Most of the time, the detection of antibodies preceded the clinical loss of response by 2 mo.

Numerous studies have confirmed the positive correlation between adalimumab levels and efficacy and the negative correlation between adalimumab antibodies (ADA) and clinical response[11,22,23].

ADA levels vary from 2.6% to 46% and have increased with the development recent methods measuring free and bound ADA[3,15,22,24-27]. The risk of developing antibodies against a second anti-TNF is increased in patients who develop antibodies against a first anti-TNF agent and in this case, they usually appear during the first year[28-31].

The notion of transient antibodies has emerged, defined as antibodies that disappear for 2 consecutive infusions. These antibodies, which appear after a median of 13.5 mo, represent 23% of antibodies[15]. Paul et al[32] studied 13 patients treated with adalimumab without concomitant therapy. Five patients had transient antibodies with no impact on clinical outcome.

Factors influencing antibody formation have been identified: Low early serum adalimumab concentrations have been shown to increase the future risk of antibody formation[15]. These concentrations have predictive value and could help as a guide to optimize treatment before symptoms develop. Higher post induction concentrations decrease the risk of antibody formation[13,15].

The level of antibodies rather than a simple positive/negative status is also important and the cut off is not known. For Yanai et al[33] ADA > 4 g/mL is predictive of failure with a 90% specificity while it is 10 ng/mL for Roblin et al[34]. All these factors influence efficacy as well as safety due to hypersensitivity reactions.

However, ADA are not the only mechanism because a loss of response was observed in up to 50% of patients while anti-ADA were detected in 10%-15% of the cases[4].

Different methods were developed to measure adalimumab and ADA with some limitations for ADA depending on the detection of non-neutralizing antibodies and of free and/or bound ADA. So the method used influences the interpretation of results.

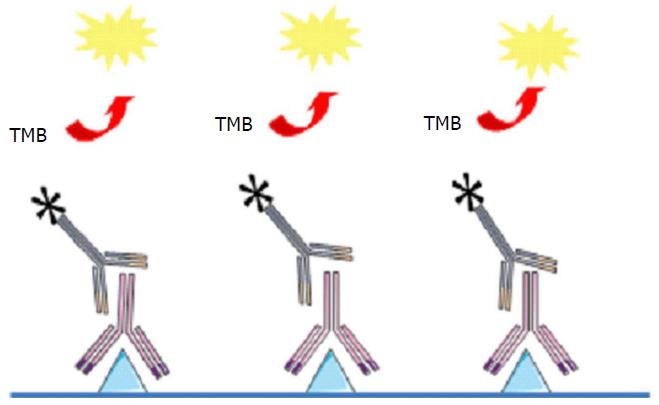

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is the most common test for measuring adalimumab levels and for ADA detection in patient serum. For drug measurement, TNF coated on the assay plate is exposed to patient serum and the presence of adalimumab is revealed by a labelled polyclonal anti-immunoglobulin (Figure 1). All anti-TNF drugs can be detected in this assay and give a signal which explains why adalimumab can be detectable with this test even if the patient is treated with another anti-TNF.

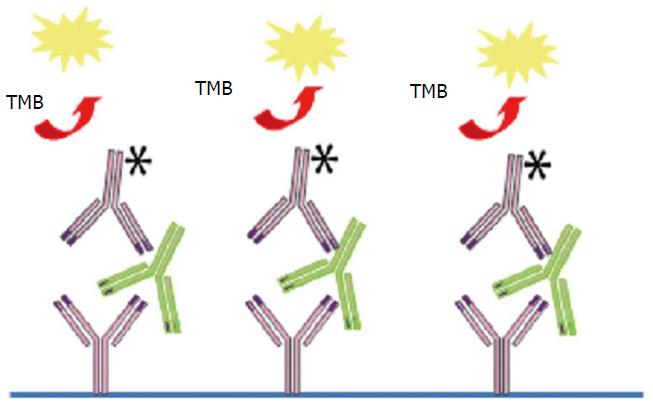

For ADA detection, the therapeutic antibody [Fab or F(ab)2 fragment] is coated on the assay plate and exposed to patient serum and the presence of ADA is revealed by a labelled therapeutic antibody (Figure 2). However, ELISA has the following limitations: Rheumatoid factors, heterophilic antibodies, both may interfere in antibody detection, ELISA may fail to detect IgG4 antibody which may dominate after prolonged immunization and anti-TNF may aggregate on plastic surfaces giving false positive results. More important ELISA is drug-sensitive and only detects free ADA. ADA cannot be detected in presence of the drug as they are complex with a risk of false negative results. Thus, certain investigators state that ADA results are inconclusive if drug levels are elevated in sera testing negative for ADA because of the presence of antibody-drug complex[35].

Different methods have been developed to overcome this problem. Separate drug-antibody complexes by acid dissociation (pH shifting) were proposed and certain authors found that 20% more ADA could be detected. Indeed the level of ADA is underestimated as they are detected only if the concentration of antibody exceeds that of the drug in the serum[36]. In a variant of this assay, the pH shift anti-idiotype antigen-binding test (PIA) was developed in which rabbit anti-idiotype Fab is added to inhibit re-formation of ADA-drug complexes (PIA)[37]. However by this process, incomplete dissociation, re-formation of complexes or even irreversible destruction of ADA binding epitopes may occur. In another test, the drug was used as a capture antibody and anti-lambda antibody was used as a detecting antibody[38].

Fluid assays were also developed to measure drugs and ADA. In the PIA, immunoglobulins from patient sera were aggregated on a protein (Sepharose) and the presence of ADA was revealed by radiolabelled anti-TNF or F(ab)2 (to avoid rheumatoid factor interference). In the homogeneous mobility-shift assay (HMSA), a fluorescent labelled anti-TNF was used to capture free and bound ADA were separated by size exclusion high performance liquid chromatography (unclear)[39]. However, as complexes could be artificially split during chromatography, non-neutralizing ADA in vivo could be detectable by PIA or HMSA with no real clinical relevance.

The last assay was the cell based reporter gene assay (RGA)[40]. This is a functional test based on the detection of TNF activity. It is less sensitive than ELISA and HMSA but highly specific for the clinical response because it detects anti-TNF activity and neutralizing anti-drug antibodies alone thus mimicking the effect of ADA in vivo. Steenholdt et al[41] recently showed that unlike HMSA and PIA which gives false positives, the results of ELISA and RGA were correlated.

The clinical relevance of low concentrations of ADA that are not detectable in drug sensitive assays has not be clarified and ELISA is actually the most commonly used test because it is easy to perform, less expensive and correlated to the cell assay detecting neutralizing ADA. However, a blood sample should be taken before the next injection and testing should not be performed on blood obtained close to when the drug is administer to be sure to measure ADA without drug interference.

Theoretically the effect of concomitant use of immunosuppressive therapy is to reduce antibody formation, to increase the anti-TNF alpha drug in serum and to decrease drug clearance for better clinical outcomes[1].

Two studies have shown that combination therapy minimizes the immunogenicity for Infliximab and Adalimumab[42,43]. In Classic 2, 2.6% (n = 7) of 269 patients developed antibodies to Adalimumab and none of the patients with concomitant immunosuppressive therapy had antibodies. Among the 7 patients with antibodies, 43% were in remission 24% and 29% at week 56. A recent study by Baert et al[15] confirmed that concomitant use of immunosuppressive therapy prevented antibody formation. In a retrospective analysis of 148 patients, a low serum adalimumab concentration in monotherapy was found to increase the risk of antibody formation. On the contrary, a high post induction drug concentration decreased the risk of antibody formation[15].

However, in their meta-analysis Paul et al[3] and Mazor et al[22] found that concomitant immunosuppressive therapy did not influence adalimumab levels. In a retrospective study among 217 patients treated with adalimumab, van Schaik et al[43] found no beneficial effect of immunosuppressive co-medication for antibody formation. The limit of the study is that they did not evaluate clinical response.

A cut off value for adalimumab levels ranged from 4.8 to 5.9 g/mL whatever the method of measurement for a clinical benefit[3].

However it is important to emphasize that the cut off value depends on the dosing method which is often different in published studies. In addition most of the assays were not compared.

Long lasting remission of CD can be optimized by maintaining adequate drug levels and preventing antibody formation. Defining predictors of response to anti-TNF alpha and indications for dose escalation will help clinicians choose the best therapy for the appropriate IBD patients with to maximize efficacy and minimize toxicity.

Dose escalation to weekly therapy was needed in 16 (4%) of patients during the 1st year of adalimumab therapy in a prospective study of 201 patients[44]. CRP at week 12 was predictive of clinical efficacy. Azathioprine decreased the probability of dose escalation in this study. In the CHARM trial of 260 patients, 27.3% changed to weekly dosing during the first year and an additional 13.1% changed to weekly dosing during the second year. In another study, 168 patients were followed-up for a median of 20.4 mo. All failed to response to infliximab. Sixty-seven percent responded to Adalimumab at week 12, 65% had to step up to 40 mg per week and 71% responded to the dose escalation. Discontinuation was related to low adalimumab levels and the presence of antibodies[24].

Dose escalation is effective for managing secondary loss of response in CD. One study followed-up 92 patients for 170 wk who achieved a primary response. Eighty percent had clinical response after dose escalation and 56% experienced tertiary loss of response[45]. For ulcerative colitis the rate of escalation was 38.4% for early non responders. At week 52, 25% were in remission[46]. A high body mass index (BMI) and non-response to infliximab were predictive for a dose escalation[7]. There are no pharmacologic data in these studies.

Pharmacokinetics can help select patients who will benefit from dose escalation. A study on mucosal healing has confirmed the association between trough adalimumab levels, clinical remission and mucosal healing[47].

Roblin et al[47] explored the clinical utility of therapeutic drug monitoring of Adalimumab in a prospective observational study. The cut off for adalimumab blood levels was 4.9 g/mL. They demonstrated that patients with low blood levels and no antibodies had a better response than patients with antibodies whatever the blood level of drug. The presence of antibodies was related to nonresponse to adalimumab.

The induction phase of treatment also influences antibody formation: Baert et al[15] showed that low early drug concentration after induction influenced the risk of antibody formation. These findings show the predictive value of measuring serum adalimumab concentrations early to guide treatment optimization before antibody formation and symptom occurrence. Patients with more severe inflammation require higher than average drug doses to obtain the necessary degree of drug exposure and optimum results.

The reason for discontinuation of infliximab was a clear clinical predictor of response to adalimumab. Among the primary non-responders to infliximab, short-term response to adalimumab was 36% compared to 83% in those who discontinued infliximab for other reasons. There is a clear relationship between serum drug concentrations, clinical effect and long term efficacy.

Mucosal healing has emerged as a major therapeutic goal in IBD. Roblin et al[47] studied the association between therapeutic drug monitoring of ADA and mucosal healing among 40 patients. They have shown that therapeutic drug monitoring of ADA was associated with clinical remission in IBD patients and the negative impact of immunogenicity. Median ADA trough levels were significantly higher in patients who achieved mucosal healing. The optimal cut-off value of ADA trough levels for predicting mucosal healing was generally similar to that observed for clinical remission.

Few studies have explored anti-TNF dosage reduction[48]. Baert et al[49] recently explored reduction in IFX dosage. For adalimumab, dose de-escacalation to every 2 wk after successful escalation was possible in 63% of patients. There are no pharmacokinetics data in this study.

One study evaluated Adalimumab doses in 6 patients treated after surgery for CD. Adalimumab trough levels in patients with clinical or endoscopic levels were lower than in those in clinical remission after a 2 years of follow-up[50]. More studies are needed to confirm these data.

Anti-TNF drugs are extensively prescribed for inflammatory diseases. Loss of response to adalimumab is frequent and the pharmacokinetics of anti-TNF therapy has important implications for patient management. The pharmacology of adalimumab is not completely understood in particular drug clearance. Individual factors such as albumin, body weight and CRP level also influence drug metabolism. Recent data have shown that there is a clinical benefit to the drug and antibody dosage for patient management. Adalimumab levels are associated with clinical remission. On the other hand, the detection of antibodies is associated with treatment failure. There is also a non-anti-TNF pathway in some patients with treatment failure and another therapeutic should then be proposed. New algorithms are available to provide personal treatment and dose adaptations. More data are needed for dose de-escalation. Monitoring drug levels and optimization of treatment without clinical relapse has not been confirmed in clinical practice.

P- Reviewer: Akiho H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Ordás I, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Therapeutic drug monitoring of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1079-1087; quiz e85-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mould DR, Dubinsky MC. Dashboard systems: Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic mediated dose optimization for monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55 Suppl 3:S51-S59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Paul S, Moreau AC, Del Tedesco E, Rinaudo M, Phelip JM, Genin C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Roblin X. Pharmacokinetics of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1288-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ordás I, Mould DR, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: pharmacokinetics-based dosing paradigms. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:635-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Affronti A, Orlando A, Cottone M. An update on medical management on Crohn’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:63-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stidham RW, Lee TC, Higgins PD, Deshpande AR, Sussman DA, Singal AG, Elmunzer BJ, Saini SD, Vijan S, Waljee AK. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: the efficacy of anti-TNF agents for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1349-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bultman E, de Haar C, van Liere-Baron A, Verhoog H, West RL, Kuipers EJ, Zelinkova Z, van der Woude CJ. Predictors of dose escalation of adalimumab in a prospective cohort of Crohn’s disease patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Schreiber S, Plevy SE, Pollack PF, Robinson AM, Chao J, Mulani P. Dosage adjustment during long-term adalimumab treatment for Crohn’s disease: clinical efficacy and pharmacoeconomics. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:141-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khanna R, Bouguen G, Feagan BG, DʼHaens G, Sandborn WJ, Dubcenco E, Baker KA, Levesque BG. A systematic review of measurement of endoscopic disease activity and mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease: recommendations for clinical trial design. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1850-1861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mould DR, Frame B. Population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of biological agents: when modeling meets reality. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50:91S-100S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moss AC, Brinks V, Carpenter JF. Review article: immunogenicity of anti-TNF biologics in IBD - the role of patient, product and prescriber factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1188-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fasanmade AA, Adedokun OJ, Ford J, Hernandez D, Johanns J, Hu C, Davis HM, Zhou H. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:1211-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Baert F, Vande Casteele N, Tops S, Noman M, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P, Gils A, Vermeire S, Ferrante M. Prior response to infliximab and early serum drug concentrations predict effects of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1324-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fasanmade AA, Adedokun OJ, Olson A, Strauss R, Davis HM. Serum albumin concentration: a predictive factor of infliximab pharmacokinetics and clinical response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;48:297-308. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Baert F, Kondragunta V, Lockton S, Vande Casteele N, Hauenstein S, Singh S, Karmiris K, Ferrante M, Gils A, Vermeire S. Antibodies to adalimumab are associated with future inflammation in Crohn’s patients receiving maintenance adalimumab therapy: a post hoc analysis of the Karmiris trial. Gut. 2015;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Lie MR, Peppelenbosch MP, West RL, Zelinkova Z, van der Woude CJ. Adalimumab in Crohn‘s disease patients: pharmacokinetics in the first 6 months of treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1202-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Garcês S, Demengeot J, Benito-Garcia E. The immunogenicity of anti-TNF therapy in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1947-1955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van Schouwenburg PA, Rispens T, Wolbink GJ. Immunogenicity of anti-TNF biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9:164-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maser EA, Villela R, Silverberg MS, Greenberg GR. Association of trough serum infliximab to clinical outcome after scheduled maintenance treatment for Crohn‘s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1248-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Takeuchi T, Miyasaka N, Tatsuki Y, Yano T, Yoshinari T, Abe T, Koike T. Baseline tumour necrosis factor alpha levels predict the necessity for dose escalation of infliximab therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1208-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, D’ Haens G, Carbonez A, Rutgeerts P. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:601-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1523] [Cited by in RCA: 1519] [Article Influence: 69.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mazor Y, Almog R, Kopylov U, Ben Hur D, Blatt A, Dahan A, Waterman M, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y. Adalimumab drug and antibody levels as predictors of clinical and laboratory response in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:620-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | West RL, Zelinkova Z, Wolbink GJ, Kuipers EJ, Stokkers PC, van der Woude CJ. Immunogenicity negatively influences the outcome of adalimumab treatment in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1122-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Karmiris K, Paintaud G, Noman M, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, Ferrante M, Degenne D, Claes K, Coopman T, Van Schuerbeek N, Van Assche G. Influence of trough serum levels and immunogenicity on long-term outcome of adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1628-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh DG, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Kent JD, Bittle B. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease: results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut. 2007;56:1232-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 708] [Cited by in RCA: 768] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ungar B, Chowers Y, Yavzori M, Picard O, Fudim E, Har-Noy O, Kopylov U, Eliakim R, Ben-Horin S. The temporal evolution of antidrug antibodies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab. Gut. 2014;63:1258-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vincent FB, Morand EF, Murphy K, Mackay F, Mariette X, Marcelli C. Antidrug antibodies (ADAb) to tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-specific neutralising agents in chronic inflammatory diseases: a real issue, a clinical perspective. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:165-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Frederiksen MT, Ainsworth MA, Brynskov J, Thomsen OO, Bendtzen K, Steenholdt C. Antibodies against infliximab are associated with de novo development of antibodies to adalimumab and therapeutic failure in infliximab-to-adalimumab switchers with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1714-1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | van Schouwenburg PA, Krieckaert CL, Rispens T, Aarden L, Wolbink GJ, Wouters D. Long-term measurement of anti-adalimumab using pH-shift-anti-idiotype antigen binding test shows predictive value and transient antibody formation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1680-1686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bartelds GM, Wijbrandts CA, Nurmohamed MT, Stapel S, Lems WF, Aarden L, Dijkmans BA, Tak PP, Wolbink GJ. Anti-infliximab and anti-adalimumab antibodies in relation to response to adalimumab in infliximab switchers and anti-tumour necrosis factor naive patients: a cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:817-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bartelds GM, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, van Schouwenburg PA, Lems WF, Twisk JW, Dijkmans BA, Aarden L, Wolbink GJ. Development of antidrug antibodies against adalimumab and association with disease activity and treatment failure during long-term follow-up. JAMA. 2011;305:1460-1468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 551] [Cited by in RCA: 602] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Paul S, Dronne W, Roblin X. Kinetics of Antibodies Against Adalimumab Are Not Associated With Poor Outcomes in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:777-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yanai H, Lichtenstein L, Assa A, Mazor Y, Weiss B, Levine A, Ron Y, Kopylov U, Bujanover Y, Rosenbach Y. Levels of drug and antidrug antibodies are associated with outcome of interventions after loss of response to infliximab or adalimumab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:522-530.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Roblin X, Rinaudo M, Del Tedesco E, Phelip JM, Genin C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Paul S. Development of an algorithm incorporating pharmacokinetics of adalimumab in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1250-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Bendtzen K. Immunogenicity of Anti-TNF-α Biotherapies: II. Clinical Relevance of Methods Used for Anti-Drug Antibody Detection. Front Immunol. 2015;6:109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Imaeda H, Takahashi K, Fujimoto T, Bamba S, Tsujikawa T, Sasaki M, Fujiyama Y, Andoh A. Clinical utility of newly developed immunoassays for serum concentrations of adalimumab and anti-adalimumab antibodies in patients with Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:100-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | van Schouwenburg PA, Bartelds GM, Hart MH, Aarden L, Wolbink GJ, Wouters D. A novel method for the detection of antibodies to adalimumab in the presence of drug reveals “hidden” immunogenicity in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Immunol Methods. 2010;362:82-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kopylov U, Mazor Y, Yavzori M, Fudim E, Katz L, Coscas D, Picard O, Chowers Y, Eliakim R, Ben-Horin S. Clinical utility of antihuman lambda chain-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) versus double antigen ELISA for the detection of anti-infliximab antibodies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1628-1633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Wang SL, Ohrmund L, Hauenstein S, Salbato J, Reddy R, Monk P, Lockton S, Ling N, Singh S. Development and validation of a homogeneous mobility shift assay for the measurement of infliximab and antibodies-to-infliximab levels in patient serum. J Immunol Methods. 2012;382:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lallemand C, Meritet JF, Blanchard B, Lebon P, Tovey MG. One-step assay for quantification of neutralizing antibodies to biopharmaceuticals. J Immunol Methods. 2010;356:18-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Steenholdt C, Bendtzen K, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, Ainsworth MA. Clinical implications of measuring drug and anti-drug antibodies by different assays when optimizing infliximab treatment failure in Crohn’s disease: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1055-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, Lichtiger S, D’Haens G, Diamond RH, Broussard DL. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2539] [Cited by in RCA: 2371] [Article Influence: 158.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | van Schaik T, Maljaars JP, Roopram RK, Verwey MH, Ipenburg N, Hardwick JC, Veenendaal RA, van der Meulen-de Jong AE. Influence of combination therapy with immune modulators on anti-TNF trough levels and antibodies in patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2292-2298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kiss LS, Szamosi T, Molnar T, Miheller P, Lakatos L, Vincze A, Palatka K, Barta Z, Gasztonyi B, Salamon A. Early clinical remission and normalisation of CRP are the strongest predictors of efficacy, mucosal healing and dose escalation during the first year of adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:911-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Ma C, Huang V, Fedorak DK, Kroeker KI, Dieleman LA, Halloran BP, Fedorak RN. Adalimumab dose escalation is effective for managing secondary loss of response in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1044-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wolf D, D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Van Assche G, Robinson AM, Lazar A, Zhou Q, Petersson J, Thakkar RB. Escalation to weekly dosing recaptures response in adalimumab-treated patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:486-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Roblin X, Marotte H, Rinaudo M, Del Tedesco E, Moreau A, Phelip JM, Genin C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Paul S. Association between pharmacokinetics of adalimumab and mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:80-84.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Pariente B, Laharie D. Review article: why, when and how to de-escalate therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:338-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Baert F, Glorieus E, Reenaers C, D’Haens G, Peeters H, Franchimont D, Dewit O, Caenepeel P, Louis E, Van Assche G. Adalimumab dose escalation and dose de-escalation success rate and predictors in a large national cohort of Crohn’s patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:154-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Bodini G, Savarino V, Peyrin-Biroulet L, de Cassan C, Dulbecco P, Baldissarro I, Fazio V, Giambruno E, Savarino E. Low serum trough levels are associated with post-surgical recurrence in Crohn’s disease patients undergoing prophylaxis with adalimumab. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:1043-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |