Published online Aug 25, 2017. doi: 10.5495/wjcid.v7.i3.46

Peer-review started: March 31, 2017

First decision: May 8, 2017

Revised: July 9, 2017

Accepted: July 21, 2017

Article in press: July 23, 2017

Published online: August 25, 2017

Processing time: 148 Days and 4.3 Hours

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is known to cause esophagitis in immunosuppressed patients; however, it is rarely seen in immunocompetent patients. We present a unique case of HSV esophagitis in a healthy male, without any immunocompromising conditions or significant comorbidities. The patient presented with a two-week history of dysphagia, odynophagia and epigastric pain. Physical exam revealed oral hyperemia without any visible ulcers or vesicles. He underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy which noted severe esophagitis with ulceration. Esophageal biopsies were positive for HSV. Serology was positive for HSV as well. After initiating treatment with Famciclovir 250 mg 3 times/d, high dose proton pump inhibitor and sucralfate, patient had complete resolution of symptoms at his 2.5 wk follow up appointment. Subsequent workup did not reveal any underlying immune disorders. While HSV is a known causative of esophagitis in the immunocompromised, its presentation in healthy patients without any significant comorbidity is uncommon. Presentation with a systemic viral prodrome further makes this case unique.

Core tip: Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is known to cause esophagitis in immunosuppressed patients but rarely does it cause esophagitis in immunocompetent patients. We present a unique case of a healthy 43-year-old man who presented with two week course of dysphagia, odynophagia, and epigastric pain. Work up, which included esophagogastroduodenoscopy, revealed severe esophagitis with ulceration and biopsies showed HSV. He was successfully treated with famciclovir.

- Citation: de Choudens FCR, Sethi S, Pandya S, Nanjappa S, Greene JN. Atypical manifestation of herpes esophagitis in an immunocompetent patient: Case report and literature review. World J Clin Infect Dis 2017; 7(3): 46-49

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3176/full/v7/i3/46.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5495/wjcid.v7.i3.46

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a known causative agent for esophagitis in the immunocompromised host. However, its presence in immunocompetent and otherwise healthy patients is rare. Patients with esophagitis often presents with concerning clinical features such as odynophagia, dysphagia, and retrosternal pain. Endoscopic visualization demonstrates mid distal esophageal ulcers[1,2]. Our case report describes a unique case of HSV esophagitis in an immunocompetent, otherwise healthy male host with an unusual prodome of symptoms.

A 43-year-old man with a past medical history of migraines presented with a 10-d history of progressively worsening dysphagia, odynophagia and burning sensation at the epigastric region with radiation to the back. Although the patient denied any oral ulcers, his symptoms were exacerbated by oral intake lasting for several hours which lead to decreased oral intake, weight loss, generalized weakness, and fatigue. He denied any changes in his bowel habits or gastrointestinal blood loss.

The patient reported a recent history of severe chills, a pustule on his face with purulent discharge, diffuse body aches, nausea, vomiting, and arthralgias. He also noted a diffuse erythematous pruritic rash on his back, lower chest and abdomen that worsened over the last week prior to presentation.

Patient was born in North Carolina and had lived in Florida for over 10 years. He denied any known allergies and denied starting any new medications including over the counter medicines or herbal medications. He reported being employed as a state trooper and denied any sick contacts or recent travel. He admitted to a 20-year history of daily alcohol use. Denied any history of smoking or illicit drug use. He did endorse having an affair with a new girlfriend with whom he had oral sex prior to onset of his symptoms.

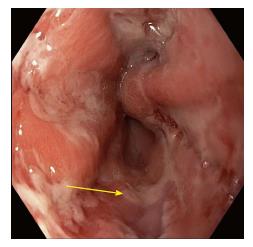

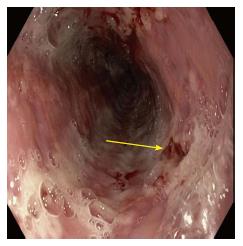

Physical examination revealed a man in no acute distress. Mild hyperemia was noted in the oropharynx without any lesions on the mucosal membranes. The patient was afebrile, acyanotic, and anicteric. Other systems were unremarkable. No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was noted. Skin exam revealed erythematous follicular rash on chest, back and lower abdomen. No insect bites or target rash was noted. Basic labs, including complete blood count and complete chemistry, were unremarkable. He underwent diagnostic testing which resulted in a positive Hepatitis A IgG. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), monospot, Lyme disease and rapid plasma reagin testing were negative. On complete blood count (CBC), he had white blood cell count of 7.7 with atypical lymphocytes that were reported at 8% of total, which was slightly higher than normal. HSV 1/2 antibody was positive. Blood cultures and urine cultures remained negative. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed severe esophagitis with evidence of erosions and superficial bleeding in the mid esophagus (Figures 1 and 2).

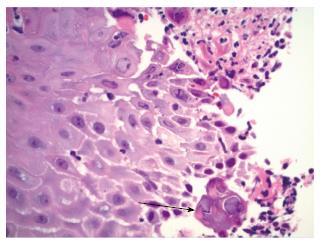

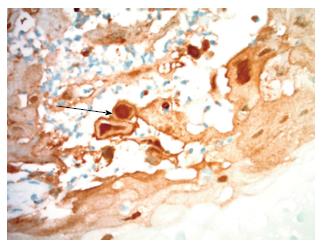

Pathology on esophageal biopsy demonstrated mild chronic inflammation with reactive changes and focal intestinal metaplasia along with positive immunohistochemical staining for HSV (Figures 3 and 4). Also, it revealed multinucleated squamous cells with margination of chromatin and molding of nuclei. Stains for cytomegalovirus (CMV) were negative and Grocott methenamine silver stain did not reveal any fungal organisms. Unfortunately, PCR for HSV-1 and 2 on biopsy specimen was reported as HSV-1/2 and no distinction could be made as to whether HSV virus in biopsy specimen was type 1 or 2. The final diagnosis on pathology report for esophageal biopsy was “HSV esophagitis with ulceration”.

Treatment with famciclovir 250 mg thrice daily, pantoprazole 40 mg daily and sucralfate was begun. Within three days of treatment initiation, patient felt well enough to be discharged home on the same regimen. He was seen at a follow up visit after two and a half weeks and reported remarkable improvement of symptoms and was able to tolerate all foods with subsequent weight gain.

HSV esophagitis is a common pathologic agent in immunocompromised patients who are on chronic immunosuppressive medications as well as patients with underlying neoplasia, organ transplant recipients and HIV infection. Infection in an immunocompetent host has been noted in rare cases and may be secondary to a primary infection or reactivation of a latent infection[3].

These infections are mostly caused by HSV-1. HSV-2 related esophagitis is extremely rare. Traditionally, the first episode of oral-facial HSV infection is caused by HSV-1 with a current rise in oral HSV-2 infections paralleling the change in sexual behaviors[2]. Also, HSV-1 is becoming a predominant cause of first episode of genital herpes in young adults[2].

Oral-facial HSV infections caused by either HSV-1 or HSV-2 can be transmitted to heterosexual partner involved in an orogenital contact. With an increasing prevalence of unprotected orogenital sexual contacts, there has been a reported increase in transmission of anogenital infections caused by HSV to the oropharynx resulting in HSV related esophagitis[2].

We believe that our patient who was recently involved in an orogenital contact with a new girlfriend and may have contracted HSV-1 or HSV-2 infection resulting in infection of his oropharynx by either HSV strain and eventually causing esophagitis.

We performed a review of all available literature on the topic and noted a paucity of data. Patients usually present with typical symptoms of dysphagia, odynophagia, retrosternal discomfort, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, cough, and epigastric pain[3]. Once noninfectious etiologies of esophagitis have been ruled out, the most common etiologies include HSV, CMV and Candida. Other etiologies should be considered in differential diagnosis of esophagitis and these include but are not limited to malignancy, esophageal stricture, reflux esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis. HSV is the second most common cause of infectious esophagitis[4]. It has been described in a wide age range and appears to have a pattern of male predominance with a ratio of 3:1[1]. Prior exposure to HSV is reported in 20% of cases[4]. Symptoms are usually characterized by acute onset of odynophagia and epigastric pain in the majority of patients with or without prodromal symptoms. These prodromal symptoms usually consist of fever, malaise, pharyngitis, and upper respiratory symptoms[5]. Oropharyngeal manifestations (herpes labialis) may be associated and has been reported in 20% of cases[5].

The distal esophagus is the most common site involved (63.8%) and usually affects with the large portions of esophageal mucosa (92.1%)[5]. In the early stages of the disease, discrete vesicles can be appreciated; these typically slough off to form circumscribed ulcers. The mucosa is friable and inflamed in most cases (84%) and can be covered with a white exudate. Late stages are characterized by mucosal necrosis[4]. Biopsies from the edge of ulcers can confirm the disease and such biopsies usually show cowdry type A inclusion bodies which are very classic for HSV related infections. Although polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is preferred for its high sensitivity (92%-100%) and specificity (100%), cell culture and virus isolation are considered the gold standard[1,3]. Direct immunofluorescence assays can be applied as a faster diagnostic tool but is limited by a sensitivity of only 69%-88%[1]. Serology is usually a poor diagnostic tool considering most adults have prior exposure to HSV, however, it can be useful in cases of primary HSV were patients experience seroconversion[4]. Although, not usually obtained, double contrast radiographic studies can visualize superficial ulcers against a background of normal mucosa[6]. Ulcers develop a punctate, stellate, or ring like configuration and may be surrounded by radiolucent mounds of edema.

The diffuse rash in our patient was of uncertain etiology. HSV may present with dermatologic manifestations in the form of erythema multiforme[7]. This is an immune mediated hypersensitivity reaction and in the setting of HSV, presents with oral lesions and a classic targetoid rash and typically resolves with HSV treatment. HSV esophagitis in an immunocompetent host is usually self-limiting and recurrence is rare. Rare complications such as upper GI bleed and perforation of the distal esophagus can occur without treatment[5].

Benefits of therapy have no clear evidence, although it has been shown to shorten duration of illness by about 6 d[4]. Due to odynophagia, IV Acyclovir is traditionally the drug of choice which can be then transitioned to oral prodrugs such as famciclovir and valaciclovir. Cases treated with acyclovir showed clinical response in less than 3 d with complete resolution of symptoms within 4-14 d of therapy[1]. Our case highlights the importance of keeping HSV esophagitis as one of the differential diagnosis for immunocompetent patients who present with symptoms suggestive of esophagitis.

A healthy 43-year-old man presented with 2 wk history of dysphagia, odynophagia, and epigastric pain radiating to back that worsened with oral intake.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed severe esophagitis with evidence of erosions and superficial bleeding in the mild esophagus. Pathology on biopsy was positive for herpes simplex virus (HSV).

With ulcerate lesions in the esophagus and odynophagia, differential is broad and includes infection, malignancy, esophageal strictures, reflux esophagitis, and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Gold standard for diagnosis is cell culture and virus isolation but PCR is preferred for its high sensitivity and specificity.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy provides direct visualization of the ulcerate lesions that characterize HSV esophagitis.

Ulcer biopsy can confirm the disease and they usually show cowdry type A inclusion bodies which are pathognomonic for HSV related infections.

Therapy has shown to shorten duration of illness and options include intravenous acyclovir or oral famcyclovir and valacyclovir.

Very few reports exist for immunocompetent patients with HSV esophagitis. It is more common in immunocompromised hosts.

EGD is abbreviation for esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

HSV esophagitis must be kept in the differential when any patient presents with odynophagia regardless of immune status.

This manuscript presents an interesting case and it is well written, organized, and informative.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Borkow G, Firstenberg MS, Krishnan T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Marinho AV, Bonfim VM, de Alencar LR, Pinto SA, de Araújo Filho JA. Herpetic esophagitis in immunocompetent medical student. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2014;2014:930459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hoyne DS, Patel Y, Katta J, Sandin RL, Greene JN. Isolated Posterior Pharyngitis. Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice. 2012;20:67-70. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, Wilson LA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1305-1313; quiz 1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Geraci G, Pisello F, Modica G, Li Volsi F, Cajozzo M, Sciumè C. Herpes simplex esophagitis in immunocompetent host: a case report. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2009;2009:717183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ramanathan J, Rammouni M, Baran J Jr, Khatib R. Herpes simplex virus esophagitis in the immunocompetent host: an overview. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2171-2176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Levine MS, Laufer I, Kressel HY, Friedman HM. Herpes esophagitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;136:863-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ladizinski B, Lee KC. Oral ulcers and targetoid lesions on the palms. JAMA. 2014;311:1152-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |