Published online Nov 25, 2013. doi: 10.5495/wjcid.v3.i4.86

Revised: October 4, 2013

Accepted: November 2, 2013

Published online: November 25, 2013

Processing time: 151 Days and 23.2 Hours

Most cases of nocardiosis are seen in immunocompromised patients. Primary lymphocutaneous is a relatively uncommon presentation of this disease that may also occurs in normal hosts. Diagnosing this infection requires a high index of suspicion since cultures can take several days to exhibit growth. The microbiology laboratory must therefore be notified about cases in which this pathogen is suspected. We report four cases of primary lymphocutaneous norcardiosis. Of particular interest is the association of three of these cases with gardening.

Core tip: Nocardiosis is an infection most often seen in immunocompromised individuals. In particular, primary cutaneous disease rarely occurs in normal hosts. We present a case series of patients that developed this infection after gardening. As nocardial infections are frequently mistaken for routine pyogenic processes and as routine cultures are rarely kept long enough to show growth, this condition should be considered in patients with such a history and cultures should be incubated for several weeks.

- Citation: Tarchini G, Ross FS. Primary lymphocutaneous nocardiosis associated with gardening: A case series. World J Clin Infect Dis 2013; 3(4): 86-89

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3176/full/v3/i4/86.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5495/wjcid.v3.i4.86

Nocardia species are ubiquitous soil-dwelling Gram-positive branching beaded bacteria that are responsible for a wide spectrum of diseases in both normal and immunocompromised patients[1,2]. Nocardia infections of the pulmonary system and disease dissemination, including secondary cutaneous involvement, are well documented in immunosuppressed patients[3,4]. We report four cases that demonstrate the classic features of primary lymphocutaneous nocardia infection. Three of these infections were associated with gardening.

A 49-year-old Hispanic man with a history of diabetes mellitus presented with swelling and redness in the left elbow after squeezing a furuncle on his left hand 2 d prior. He had no fever and did not recall any injury or trauma to the hand. On physical exam, he had a furuncle with visible pus on the dorsum of the left ring finger. He also exhibited erythema and edema up to the left elbow with streaks of lymphangitis. He had a normal white blood cell count (WBC) count of 7.0 K/μL and an elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) of 6.6 mg/L. He was admitted and treated with intravenous clindamycin for 2 d. The lesion was incised and drained and the purulent fluid was sent for cultures. He was discharged on oral cephalexin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for suspected methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The Gram stain revealed the presence of Gram-positive beaded rods 3 d after admission. Nocardia brasiliensis was found by sequence identification 25 d after the initial admission. Treatment with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was continued for 6 mo.

A 59-year-old Hispanic man with a history of esophageal cancer with metastases to the lung and hypertension presented to his primary care physician with left calf redness, swelling and pain. The symptoms started after manipulating a furuncle on his left calf. Two days prior to this, he had been working in his garden and had knelt down in soil. He had not received any chemotherapy in the last 2 years. He was started on oral cephalexin but after 2 d, he developed rigors, diaphoresis and fever. He therefore returned to the emergency room and was admitted. On physical exam, he was afebrile and had a 1 cm ulcer with purulent discharge on the posterior aspect of his left calf. The surrounding area was erythematous and tender but not fluctuant or indurated. He had an area of erythema on the medial aspect of the left thigh with tender left inguinal lymphadenopathy. The largest lymph node was about 1 cm in diameter. The patient exhibited lymphangitis along the medial aspect of the lower extremity (Figure 1). He had a normal WBC count of 8.2 K/μL, elevated CRP of 31.2 mg/L, alkaline phosphatase of 341 U/L, AST of 41 U/L and total bilirubin of 2.2 mg/dL. The wound was incised and drained and the fluid sent for cultures. He was started on vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam. The Gram stain showed Gram-positive beaded rods 3 d after admission. He was discharged on oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Final cultures were positive for Nocardia brasiliensis by sequence identification 37 d after admission. Treatment with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was continued for a total of 6 mo with complete resolution of symptoms.

A 78-year-old Caucasian man with a history of prostate cancer and coronary artery disease presented to his primary care physician with a right knee lesion that had started as a small furuncle one week prior. He had been gardening and kneeling in the soil recently. Due to concerns for septic arthritis, an aspiration of the knee was attempted but no fluid was recovered. He was started on an outpatient regimen with oral doxycycline. After 2 d, he developed a new erythema over his right thigh. He therefore returned to the emergency room and was admitted to the hospital. On physical exam, he was afebrile and his right knee was erythematous. He had a suppurative lesion in the subpatellar region and there were multiple indurated and erythematous areas in a linear pattern from the patella to just below the femoral ligament. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. He had a normal WBC count of 8.6 K/μL and an elevated CRP of 56 mg/L. The area was incised and drained and the fluid sent for cultures. He was started on intravenous vancomycin. He was discharged after 2 d on oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Fungal cultures were positive for partial acid-fast thin-branched filaments 6 d after admission. The organism was identified as Nocardia brasiliensis 39 d after admission. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was stopped because of a rising creatinine level and he was switched to amoxicillin/clavulanate and minocycline. The treatment was continued for a total of 6 mo with complete resolution of symptoms.

A 62-year-old Caucasian man living in the Bahamas presented to his primary care physician with a right knee lesion associated with pain, redness, swelling and warmth for the last 3 d. About a week prior to developing these symptoms, he had noticed a small scratch in the same area. This wound had not been covered while gardening and he had been kneeling in soil on his bare knees. He had a past medical history of ulcerative colitis being treated with infliximab. As his symptoms worsened, he decided to seek care at our facility. On physical exam, he was afebrile, had a 2 cm × 3 cm × 1 cm abscess on the right knee, right inguinal lymphadenitis and signs of lymphangitis along the medial thigh. He had a normal WBC count of 7.0 K/μL and an elevated CRP of 24.5 mg/L. His alkaline phosphatase was 69 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 67 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase 45 U/L. He was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone and his infliximab therapy was put on hold. Gram positive beaded rods were seen on the Gram stain 3 d after admission. The organism was identified as Nocardia brasiliensis 10 d later. He was then switched to oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. After 6 mo of therapy, his infliximab therapy was resumed. Given the need for treatment with his immunomodulator, he was continued on prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole indefinitely.

The Nocardia genus belongs to the order Actinomycetales, a group of gram-positive, aerobic, branching, beaded, partially acid-fast bacteria[5]. They are ubiquitous in nature and can be found in soil, air, and water[1,6]. Nocardia asteroides is the most common species associated with human disease[7]. There may be geographic variation in Nocardia species distribution with more case of Nocardia brasiliensis observed in the Southern United States[4].

The exact incidence of nocardiosis is difficult to estimate but approximately 1000 cases occur annually in the United States[8,9]. Nocardia infections of the pulmonary system and disease dissemination, including secondary cutaneous involvement, are well documented in immunosuppressed patients[1,2]. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis accounts for up to 5% of all cases of nocardiosis and is more often associated with Nocardia brasiliensis[2,3,10,11].

Primary cutaneous nocardiosis results from direct inoculation of the organism into the skin as a result of minor trauma, thorn puncture or insect bite[5,10,11]. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis may cause ulceration, pyoderma, cellulitis, nodules or subcutaneous abscesses. Patients commonly present with pain, swelling, erythema and warmth[2,3,6]. It can be clinically indistinguishable from other bacterial infections such as the ones caused by Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococci.

Lymphocutaneous nocardiosis occurs when a primary nocardial skin infection involves and spreads within the lymphatic system. The clinical picture of lymphocutaneous nocardiosis could look similar to infections caused by Sporothrix schenckii or atypical mycobacterial infection[7,10]. However, in nocardia infections, the presentation is usually more acute.

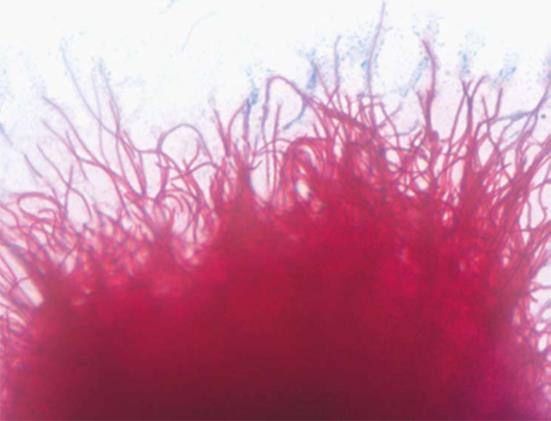

Nocardia are relatively slow-growing organisms that can be grown on standard blood agar but prefer enriched media such as Lowenstein Jensen or Sabouraraud-dextrose agar. They typically appear as white, yellow, or orange rugous colonies (Figure 2). On microscopy, nocardia appears as aerial filaments that break up into small bead-like spores (Figure 3). Routine cultures usually require 5-21 d to exhibit growth, which may lead to underdiagnosis if the organism is not seen on Gram staining since most routine cultures are discarded after 3 d of incubation[6].

The standard treatment for nocardiosis is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Surgical debridement of purulent lesions may be needed to optimize therapy. While no definitive length of treatment has been established, the patient should be treated for at least 6 mo to prevent relapse. Longer treatment courses should be considered in immunosuppressed patients[2,6,8,10,12].

Our case series is of particular interest because three of the four patients had had recent exposure to soil while gardening. In addition, two of them recalled having a small wound on their knee prior to kneeling on soil. We believe that the patients inoculated themselves with the organism at that time. We therefore suggest that a careful history should be taken with specific questions about soil exposure in patients presenting with symptoms similar to those described. In addition, we suggest that a modified acid-fast stain be performed and that cultures be kept for 21 d in such cases.

Nocardiosis is an infection most often seen in immunocompromised individuals. Infections most commonly affect the lungs and are more often associated with Nocardia asteroides. Primary cutaneous disease rarely occurs in normal hosts and is typically associated with significant soil contact. In these cases, the main pathogen is Nocardia brasiliensis. Nocardial infections are frequently mistaken for routine pyogenic processes, as routine cultures are rarely kept long enough to show growth. Sulfa-containing regimens are often effective in treating nocardia infections and treatment should be continued for at least 6 mo.

We would like to thank Margret Oethinger, MD PhD, Clinical Pathology, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 44106 for the pictures.

P- Reviewer: Randhawa HS S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Iwasawa MT, Togawa Y, Kamada N, Kambe N, Matsue H, Yazawa K, Yaguchi T, Mikami Y. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia vinacea in a patient with polymyositis. Mycopathologia. 2011;172:47-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dodiuk-Gad R, Cohen E, Ziv M, Goldstein LH, Chazan B, Shafer J, Sprecher H, Elias M, Keness Y, Rozenman D. Cutaneous nocardiosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1380-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fukuda H, Saotome A, Usami N, Urushibata O, Mukai H. Lymphocutaneous type of nocardiosis caused by Nocardia brasiliensis: a case report and review of primary cutaneous nocardiosis caused by N. brasiliensis reported in Japan. J Dermatol. 2008;35:346-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lederman ER, Crum NF. A case series and focused review of nocardiosis: clinical and microbiologic aspects. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83:300-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Folgaresi M, Ferdani G, Coppini M, Pincelli C. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:430-431. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ichikawa Y, Nakayama Y, Hata J, Umebayashi Y, Ito M. Cutaneous nocardiosis caused by Nocardia africana on the lower thigh. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:e503-e505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Baradkar VP, Mathur M, Kulkarni SD, Kumar S. Sporotrichoid pattern of cutaneous nocardiasis due to Nocardia asteroids. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:432-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Walensky RP, Moore R. A Case Series of 59 Patients with Nocardiosis. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2001;10:249-254. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sharma NL, Mahajan VK, Agarwal S, Katoch VM, Das R, Kashyap M, Gupta P, Verma GK. Nocardial mycetoma: diverse clinical presentations. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:635-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Maraki S, Chochlidakis S, Nioti E, Tselentis Y. Primary lymphocutaneous nocardiosis in an immunocompetent patient. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2004;3:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Inamadar AC, Palit A. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis: a case study and review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:386-391. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Gosselink C, Thomas J, Brahmbhatt S, Patel NK, Vindas J. Nocardiosis causing pedal actinomycetoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;47:457-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |