Published online Mar 20, 2024. doi: 10.5493/wjem.v14.i1.87551

Peer-review started: August 21, 2023

First decision: November 28, 2023

Revised: December 18, 2023

Accepted: December 26, 2023

Article in press: December 26, 2023

Published online: March 20, 2024

Processing time: 211 Days and 2.7 Hours

Prisons can be a reservoir for infectious diseases, including severe acute respira

To investigate the SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology in prisons, this study evaluated the infection incidence rate in prisoners who underwent nasopharyngeal swabs.

This is an observational cohort study. Data collection included information on prisoners who underwent nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2 and the results. Nasopharyngeal swab tests for SARS-CoV-2 were performed between 15 February 2021 and 31 May 2021 for prisoners with symptoms and all new arrivals to the facility. Another section included information on the diagnosis of the disease according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Clinical Modification.

Up until the 31 May 2021, 79.2% of the prisoner cohort (n = 1744) agreed to a nasopharyngeal swab test (n = 1381). Of these, 1288 were negative (93.3%) and 85 were positive (6.2%). A significant association [relative risk (RR)] was found only for the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection among foreigners compared to Italians [RR = 2.4, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.2-4.8]. A positive association with SARS-CoV-2 infection was also found for inmates with at least one nervous system disorder (RR = 4, 95%CI: 1.8-9.1). The SARS-CoV-2 incidence rate among prisoners is significantly lower than in the general population in Tuscany (standardized inci

In the prisoner cohort, screening and rapid access to health care for the immigrant population were critical to limiting virus transmission and subsequent morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population.

Core Tip: Prisons can be a reservoir for infectious diseases. Based on this premise, this study evaluated the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in prisons. A significant association was found in the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in foreigners compared to Italians, in particular those with at least one nervous system disorder. The SARS-CoV-2 incidence rate in prisoners is significantly lower than in the general population in Tuscany. In the prisoner cohort, screening and rapid access to health care for the immigrant population were critical to limiting virus transmission and subsequent morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population.

- Citation: Stasi C, Pacifici M, Milli C, Profili F, Silvestri C, Voller F. Prevalence and features of SARS-CoV-2 infection in prisons in Tuscany. World J Exp Med 2024; 14(1): 87551

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-315x/full/v14/i1/87551.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5493/wjem.v14.i1.87551

The prison environment can be a place where infectious diseases, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), can be amplified and spread due to the very intimate nature of the living spaces and the large number of people forced to share them (both prisoners and prison staff).

According to the international literature, the crude incidence rate for SARS-CoV-2 calculated in the prison population (September 2020) in England[1] was 988.1/100000 population at risk and did not differ significantly from that in the general population [935.3/100000 population at risk; relative risk (RR) 1.05; P = 0.14]. The results from a study carried out in Massachusetts (July 2020) showed a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) positivity rate 2.91 times higher [95% confidence interval (CI): 2.69-3.14] than in the general local population and 4.80 times higher (95%CI: 4.45-5.18) than in the general United States population[2].

A recent study by Stufano et al[3] performed a COVID-19 screening campaign by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on 515 inmates from 4 to 30 January 2022. In addition, 101 serum samples collected from healthy inmates 21 d after receiving a second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine were tested for neutralizing antibodies against both wild-type SARS-CoV-2 and the Omicron BA.1 variant. The global prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the study period was 43.6% (RR = 0.8), significantly lower than that of unvaccinated inmates (62.7%). The proportion testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 in unvaccinated subjects was significantly higher than in the other groups (P < 0.001) receiving one dose (52.3%), two doses (full cycle; 45.0%), and the third dose (booster; 31.4%).

In Italy, the data published weekly by the Ministry of Justice cannot be used to calculate specific incidence or prevalence rates because of the lack of details on the cases published. However, according to the XVII Report on detention conditions-COVID-19 and the pandemic in Italy, in February 2021, published by the Antigone Association[4], the average rate of positive cases in prisons was 91.1 per 10000 inmates, compared with 68.3 per 10000 in the general population[4].

Based on these premises, this study evaluated the epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection in prisons.

This is a cross-sectional study, with health status assessed at a single point in time. The study population was represented by all the inmates present in the prisons of Tuscany on 15 February 2021. From 15 January to 10 February, web meetings were organized with the representatives of the health care facilities to explain the data entry form and the methods for completion. On 14 February 2021, the list of inmates present in the prison was drawn up, including the new arrivals on that day (at midnight on 14 February). From 15 February 2021, doctors had 3 mo to complete the health status form for all detained citizens present on 14 February 2021.

For this study, we used specific clinical data created using the Python programming language. The data was divided into different areas: Socio-demographic, health, drugs and two other areas containing specific information about suicide attempts and self-harm, including any episodes in the last year of detention, number of episodes and method.

The first area included general information such as age, sex, nationality, origin of the prisoner (outside prison, another prison, Diagnostic Therapy Centre, social care or house arrest), daily tobacco and cigarette consumption, weight and height to calculate body mass index (BMI), and the number of hours per day spent in their cell. During this data collection, we also recorded whether the prisoner had already completed a nasopharyngeal swab test for SARS-CoV-2 and the result. All prisoners who had a nasopharyngeal swab test for SARS-CoV-2 were tested between the start of the pandemic and 31 May 2021, both for presenting symptoms and for new arrivals to the facility. These were compared with nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2 in the general population between the start of the pandemic and 31 May 2021. The second area included information on all disease diagnoses (one primary diagnosis and an unlimited number of secondary diagnoses) relating to both general medical health and mental/psychiatric health according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Clinical Modification.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in Edinburgh, 2000). According to Italian legislation on data confidentiality, the dataset used is not openly available (Decree No. 196/2003). No identifiable data were used in this study.

The association between positive swabs and other health aspects was investigated using the binomial Poisson model to estimate the RR for each factor considered with respect to the baseline category. The factors considered were place of birth (Italy/abroad), BMI, and the presence of at least one disease (infectious, nervous system, psychiatric, endocrine and immune system or cardiovascular disease, considered separately).

Chi-squared tests were used to identify any significant differences at the 95% level between swab results and the presence of at least one disease (in general, psychiatric, infectious, cardiovascular, endocrine and immune system, digestive system, respiratory system, musculoskeletal and connective apparatus, genitourinary system, nervous system, traumatic, hematological, cutaneous and subcutaneous, or neoplastic).

Standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) with approximated 95%CIs were calculated in order to compare the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 between the local population in Tuscany and the prisoners, in general and stratified by socio-demographic characteristics (age and nationality). Approximate CI were constructed using the Wilson and Hilferty[5] (1931) approximation for chi-square percentiles. The SARS-CoV-2 incidence rate in the local population was calculated using the Tuscany SARS-CoV-2 database and the number of people who tested positive between the start of the pandemic and 31 May 2021 as a proportion of the general population aged 18 years and over.

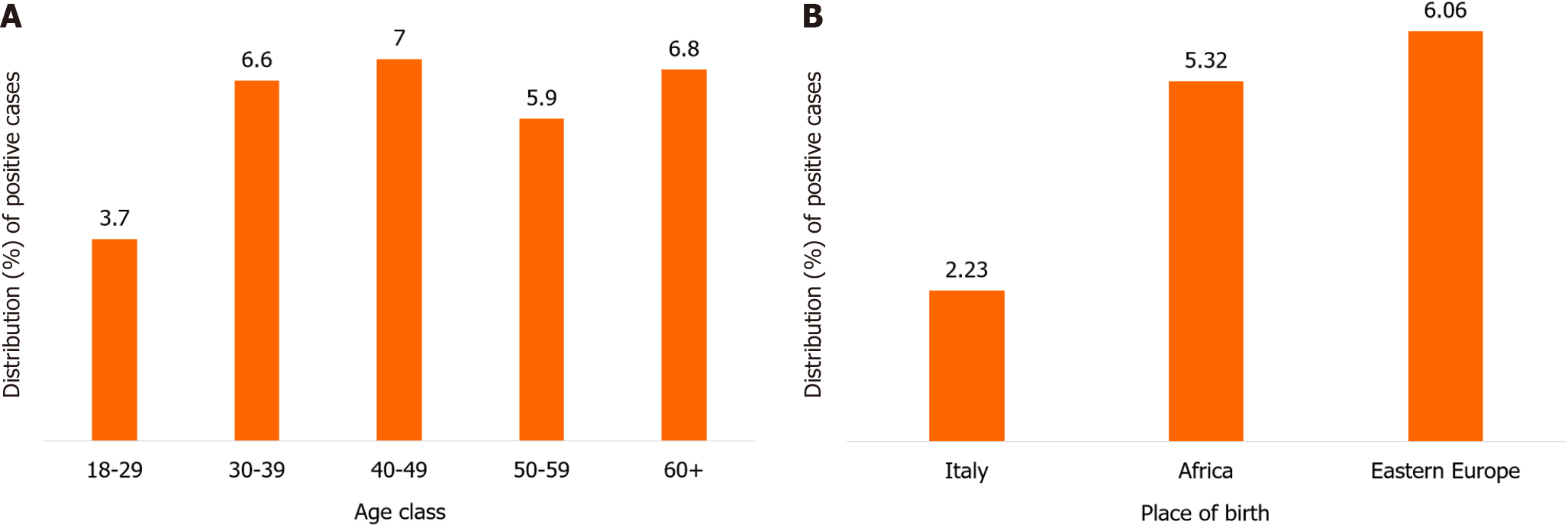

At the index date (31 May 2021), 79.2% of the inmates in our cohort (n = 1744) agreed to a nasopharyngeal swab test (n = 1381). Of these, 1288 were negative (93.3%) and 85 were positive (6.2%), while the results of the swab test were not recorded in 8 cases; this was compared with the positivity rate (4.1%) recorded in the general population. Figure 1 shows the bar plot for positive swabs (%) by age group (Figure 1A). The positive swab tests were most common among inmates from Eastern Europe and Africa (Figure 1B).

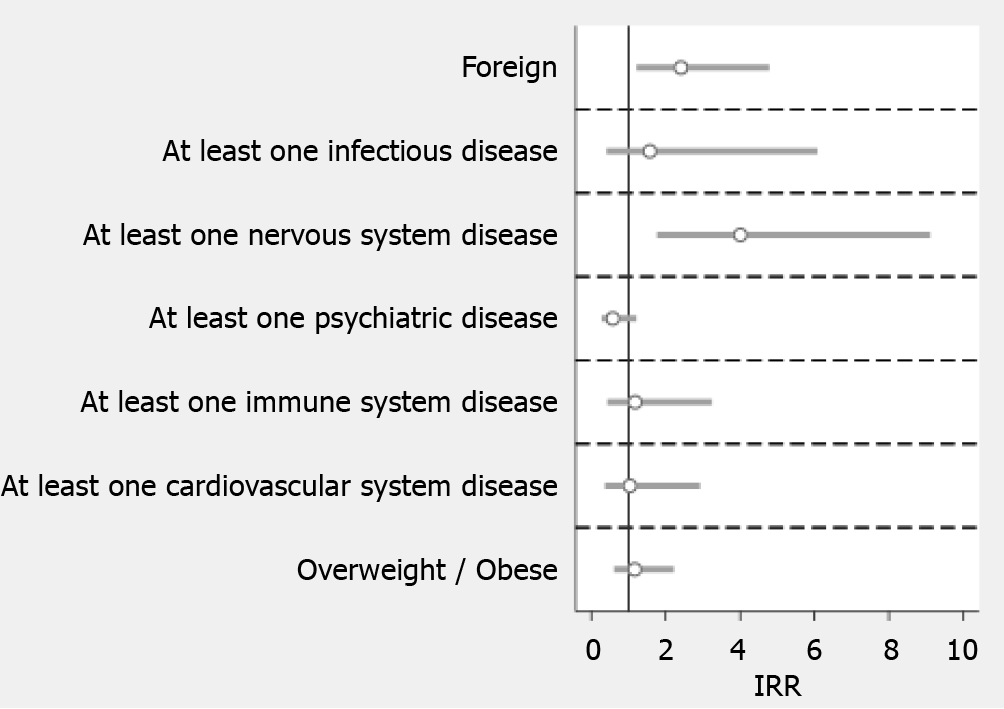

A significant association (RR) was found only for the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in foreigners compared to Italians (Figure 2) (RR = 2.4, 95%CI: 1.2-4.8). In addition to socio-demographic characteristics, we examined the association between positive swabs and other health aspects by applying the binomial Poisson model to estimate the RR for each factor considered compared to the baseline category (Figure 2). A positive association was confirmed for inmates with at least one nervous system disorder (RR = 4, 95%CI: 1.8-9.1).

Chi-squared tests showed significant differences in swab results between inmates with at least one disease and those who were disease-free (Table 1). In particular, only 5.1% of prisoners with at least one disease had a positive swab compared to 8.3% of healthy prisoners (P < 0.05). Similar differences were found between those with at least one psychiatric, digestive system or respiratory system disease and healthy inmates.

| Parameter | Negative1 | Positive1 | P value |

| Diseases in general | |||

| At least one disease | 867 (94.9) | 47 (5.1) | < 0.05 |

| No disease | 421 (91.7) | 38 (8.3) | |

| Psychiatric | |||

| At least one disease | 435 (96.2) | 17 (3.8) | < 0.05 |

| No disease | 853 (92.6) | 68 (7.4) | |

| Infectious | |||

| At least one disease | 58 (93.6) | 4 (6.4) | 0.9 |

| No disease | 1230 (93.8) | 81 (6.2) | |

| Cardiovascular | |||

| At least one disease | 157 (93.5) | 11 (6.5) | 0.8 |

| No disease | 1131 (93.9) | 74 (6.1) | |

| Endocrine and immune system | |||

| At least one disease | 138 (92) | 12 (8) | 0.3 |

| No disease | 1150 (94) | 73 (6) | |

| Digestive system | |||

| At least one disease | 165 (97.6) | 4 (2.4) | < 0.05 |

| No disease | 1123 (93.3) | 81 (6.7) | |

| Respiratory system | |||

| At least one disease | 65 (100) | 0 (0) | < 0.05 |

| No disease | 1223 (93.5) | 85 (6.5) | |

| Musculoskeletal and connective apparatus | |||

| At least one disease | 97 (95.1) | 5 (4.9) | 0.6 |

| No disease | 1191 (93.7) | 80 (6.3) | |

| Genitourinary system | |||

| At least one disease | 56 (94.9) | 3 (5.1) | 0.7 |

| No disease | 1232 (93.8) | 82 (6.2) | |

| Nervous system | |||

| At least one disease | 64 (90.1) | 7 (9.9) | 0.2 |

| No disease | 1224 (94) | 78 (6) | |

| Traumas | |||

| At least one trauma or poisoning | 33 (94.3) | 2 (5.7) | 0.9 |

| No traumas or poisoning | 1255 (93.8) | 83 (6.2) | |

| Blood organs | |||

| At least one disease | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.4 |

| No disease | 1277 (93.8) | 85 (6.2) | |

| Tumour | |||

| At least one tumour | 20 (95.2) | 1 (4.8) | 0.8 |

| No tumours | 1268 (93.8) | 84 (6.2) | |

| Cutaneous and subcutaneous | |||

| At least one disease | 49 (96.1) | 2 (3.9) | 0.5 |

| No disease | 1239 (93.7) | 83 (6.3) |

The incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 in prisoners is significantly lower than in the general local population in Tuscany (SIR 0.7, 95%CI: 0.6-0.9) (Table 2). In terms of age groups, the results were comparable only among prisoners aged 18-29 years.

| Parameter | SIR | 95%CI |

| Total | 0.7 | 0.6-0.9 |

| Age in yr | ||

| 18-29 | 0.4 | 0.2-0.8 |

| 30-39 | 0.8 | 0.5-1.1 |

| 40-49 | 0.8 | 0.5-1.1 |

| 50-59 | 0.6 | 0.4-1 |

| 60 + | 1 | 0.5-1.8 |

| Nationality | ||

| Italian | 0.3 | 0.2-0.5 |

| Foreign | 0.5 | 0.3-0.7 |

In March 2020, the World Health Organization published the guidance document “Preparedness, prevention and control of COVID-19 in prisons and other places of detention”, which provided updated information on COVID-19 case definitions, management strategies, vaccine availability and distribution procedures and indicators recommended for surveillance purposes in detention settings[6]. Although people living in close proximity to each other are likely to be more susceptible to COVID-19 than the general population, the percentage of SARS-CoV-2 infection found in the Tuscan prison was in line with that reported in other studies[7]. In fact, due to the particularly stringent prevention and control measures in place in prisons, the rate of positive cases in some studies was comparable to that in the general population. In line with our study, a recently published Italian article[8] conducted between 1 October and 31 December 2020 on 504 prisoners who underwent antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic tests showed that 21 (4.2%) were positive for viremia. In fact, Augustynowicz et al[9] showed that based on the results of a study conducted in Poland, infections among prison officers and staff as well as inmates seem parallel to the epidemiological situation in the general population[9]. Contrary to our observations, a study conducted in a prison in Barcelona[10] highlighted a high percentage (24.1%) of people who tested positive by RT-PCR. Of these, 94.8% were asymptomatic. The same high prevalence was found in a study evaluating the percentage of SARS-CoV-2-infected inmates, health care professionals, and prison officers in prisons in Espírito Santo. Specifically, among 1830 individuals, the prevalence of COVID-19 infection was 11.89% among health care professionals, 22.07% among prison officers, and 31.64% among inmates[11].

In England, prison-associated cases accounted for < 1% of COVID-19 cases from 16 March to 12 October 2020[1]. In their study of incarcerated men in Canada, Kronfli et al[7] showed that a total of 246/1100 (22%) participants tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Similar to the general population, the risk increases with age. When the incidence rates among prisoners were compared with those of the general population in Tuscany, according to the different age groups, a statistically significant difference was found only in the 18-29 age group. The data from the Canadian study showed a high prevalence compared with our data (6%); moreover, the incarcerated men who tested positive had several prison-related modifiable risk factors associated with increased seropositivity, such as length of time spent in prison, employment, consumption of communal meals during incarceration, and post-prison outbreak.

Our study found a significant association in the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in foreigners compared with Italians, which is in line with previous studies in the general population. These studies have shown that the socioeconomic and living conditions of migrants may contribute to increased rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection, with a subsequent higher risk of COVID-19 mortality[12-13]. Marquez et al[14], analyzing the mortality patterns of the population incarcerated in Texas state prisons during both the year before (from 1 April 2019) and the 1st year (from 1 April 2020) of the COVID-19 pandemic, found that COVID-19 mortality was 1.61 and 2.12 times higher in the black and Hispanic populations, respectively, compared with the white population. A study conducted from 23 December 2020 to 19 February 2021 in Lombardy, one of the Italian regions most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, showed that the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in the general population was 12.4%, with this proportion more than doubled in foreigners (23.3%) compared with Italians (9.1%)[15].

The spread of SARS-CoV-2 from October 2020 was characterized by the so-called “British” variant, a significantly more contagious variant of SARS-CoV-2 that was responsible for increasing nosocomial infections or the spread of the virus in closed environments such as prisons, despite the containment measures put in place.

Few studies have investigated the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first waves. To the best of our knowledge, this study was one of the first studies to be conducted in Italy on SARS-CoV-2 infection in a large cohort of prisoners who underwent nasopharyngeal swab testing. Therefore, its strength is the very early detection of the epidemic situation in the prison setting. Its limitation is the lack of data relating on prison and health staff during the same period in Tuscany.

In conclusion, although the control and management of SARS-CoV-2 infection in some prisons was similar to that outside, campaigns to improve disease prevention and screening, and rapid access to health care for the migrant population in prisons are critical to limiting transmission of the virus and subsequent morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population.

In conclusion, although the control and management of SARS-CoV-2 infection in some prisons was similar to that outside, campaigns to improve disease prevention and screening, and rapid access to health care for the migrant population in prisons are critical to limiting transmission of the virus and subsequent morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population.

Prisons can be a reservoir for infectious diseases, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), due to the very intimate nature of the living spaces and the large number of people forced to share them. Therefore, in this place infectious diseases, including SARS-CoV-2, can be amplified and spread.

The main motivation was to improve epidemiological knowledge, aimed at better understanding what action could be taken to improve the health status of the detained population.

Based on these premises, this study evaluated the epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection in prisons.

This is a cross-sectional study, with health status assessed at a single point in time. The study population was represented by all the inmates present in the prisons of Tuscany on 15 February 2021. Data collection included information on prisoners who underwent nasopharyngeal swab testing for SARS-CoV-2 and the results. Nasopharyngeal swab tests for SARS-CoV-2 were performed between 15 February 2021 and 31 May 2021 for prisoners with symptoms and all new arrivals to the facility. Another section included information on the diagnosis of the disease according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Clinical Modification.

A high percentage of prisoners agreed to take the swab. This high adherence was probably due to a perception of risk. A significant association was found only for the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection among foreigners compared to Italians but the SARS-CoV-2 incidence rate among prisoners is significantly lower than in the general population in Tuscany, probably due to the high level of attention of prison staff towards this public health problem.

Although the control and management of SARS-CoV-2 infection in some prisons was similar to that outside, campaigns to improve disease prevention and screening, and rapid access to health care for the migrant population in prisons are critical to limiting transmission of the virus and subsequent morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population.

Future research is needed to definitively establish a screening program to manage organized screening programs for high-prevalence infectious diseases in the prison population.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liao Z, Singapore S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Rice WM, Chudasama DY, Lewis J, Senyah F, Florence I, Thelwall S, Glaser L, Czachorowski M, Plugge E, Kirkbride H, Dabrera G, Lamagni T. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in Prisons, England, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:2183-2186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jiménez MC, Cowger TL, Simon LE, Behn M, Cassarino N, Bassett MT. Epidemiology of COVID-19 Among Incarcerated Individuals and Staff in Massachusetts Jails and Prisons. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2018851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stufano A, Buonvino N, Trombetta CM, Pontrelli D, Marchi S, Lobefaro G, De Benedictis L, Lorusso E, Carofiglio MT, Vasinioti VI, Montomoli E, Decaro N, Lovreglio P. COVID-19 Outbreak and BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccination Coverage in a Correctional Facility during Circulation of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 Variant in Italy. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Antigone. Oltre il virus. XVII Rapporto di Antigone sulle condizioni di detenzione. [cited 23 Dec 2023]. Available from: http://www.antoniocasella.eu/nume/Antigone_marzo21.pdf. |

| 5. | Wilson EB, Hilferty MM. The Distribution of Chi-Square. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1931;17:684-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 484] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | World Health Organization; Regional Office for Europe. Preparedness, prevention and control of COVID-19 in prisons and other places of detention: Interim guidance. Feb 8, 2021. [cited 21 Dec 2023]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/339830. |

| 7. | Kronfli N, Dussault C, Maheu-Giroux M, Halavrezos A, Chalifoux S, Sherman J, Park H, Del Balso L, Cheng MP, Poulin S, Cox J. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Among Incarcerated Adult Men in Quebec, Canada, 2021. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75:e165-e173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mazzilli S, Oliani F, Restivo A, Giuliani R, Tavoschi L, Ranieri R. Antigenic rapid test for SARS-CoV2 screening of individuals newly admitted to detention facilities: sensibility in an asymptomatic cohort. J Clin Virol Plus. 2021;1:100019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Augustynowicz A, Wójcik M, Bachurska B, Opolski J, Czerw A, Raczkiewicz D, Pinkas J. COVID-19 - Infection prevention in prisons and jails in Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2021;28:621-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marco A, Gallego C, Pérez-Cáceres V, Guerrero RA, Sánchez-Roig M, Sala-Farré RM, Fernández-Náger J, Turu E. Public health response to an outbreak of SARS-CoV2 infection in a Barcelona prison. Epidemiol Infect. 2021;149:e91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Silva AID, Maciel ELN, Duque CLC, Gomes CC, Bianchi EDN, Cardoso OA, Lira P, Jabor PM, Zanotti RL, Sá RT, Magno Filho SJS, Zandonade E. Prevalence of COVID-19 infection in the prison system in Espírito Santo/Brazil: persons deprived of liberty and justice workers. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2021;24:e210053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alahmad B, AlMekhled D, Odeh A, Albloushi D, Gasana J. Disparities in excess deaths from the COVID-19 pandemic among migrant workers in Kuwait. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adams ML, Katz DL, Grandpre J. Population-Based Estimates of Chronic Conditions Affecting Risk for Complications from Coronavirus Disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1831-1833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Marquez N, Moreno D, Klonsky A, Dolovich S. Racial And Ethnic Inequalities In COVID-19 Mortality Within Carceral Settings: An Analysis Of Texas Prisons. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41:1626-1634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pagani G, Conti F, Giacomelli A, Oreni L, Beltrami M, Pezzati L, Casalini G, Rondanin R, Prina A, Zagari A, Rusconi S, Galli M. Differences in the Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Access to Care between Italians and Non-Italians in a Social-Housing Neighbourhood of Milan, Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |