Published online Aug 7, 2020. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v9.i3.54

Peer-review started: April 6, 2020

First decision: June 8, 2020

Revised: June 8, 2020

Accepted: July 19, 2020

Article in press: July 19, 2020

Published online: August 7, 2020

Processing time: 121 Days and 19 Hours

Mass methanol poisonings are challenging, especially in regions with no preparedness, management guidelines and available antidotes.

Six Ukrainian patients were referred to our emergency department in Cairo, Egypt several hours after drinking an alcoholic beverage made of 70%-ethanol disinfectant bought from a local pharmacy. All patients presented with severe metabolic acidosis and visual impairments. Two were comatose. Management was based on the clinical features and chemistry tests due to deficient resources for methanol leveling. No antidote was administered due to fomepizole unavailability and the difficulties expected to obtain ethanol and safely administer it without concentration monitoring. One patient died from multiorgan failure, another developed blindness and the four other patients rapidly improved.

This methanol poisoning outbreak strongly highlights the lack of safety from hazardous pharmaceuticals sold in pharmacies and limitations due to the lack of diagnostic testing, antidote availability and staff training in countries with limited-resources such as Egypt.

Core tip: Mass methanol poisoning with unpredictable risk assessment represents a major threat in developing countries. This work reports a clinical series with patients' features and outcome, describes the investigations to identify rapidly the involved causative agent (here, a homemade beverage made with alcoholic disinfectant) and discusses the observed insufficiencies to improve hospital preparedness in case of methanol poisoning outbreak.

- Citation: Gouda AS, Khattab AM, Mégarbane B. Lessons from a methanol poisoning outbreak in Egypt: Six case reports. World J Crit Care Med 2020; 9(3): 54-62

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v9/i3/54.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v9.i3.54

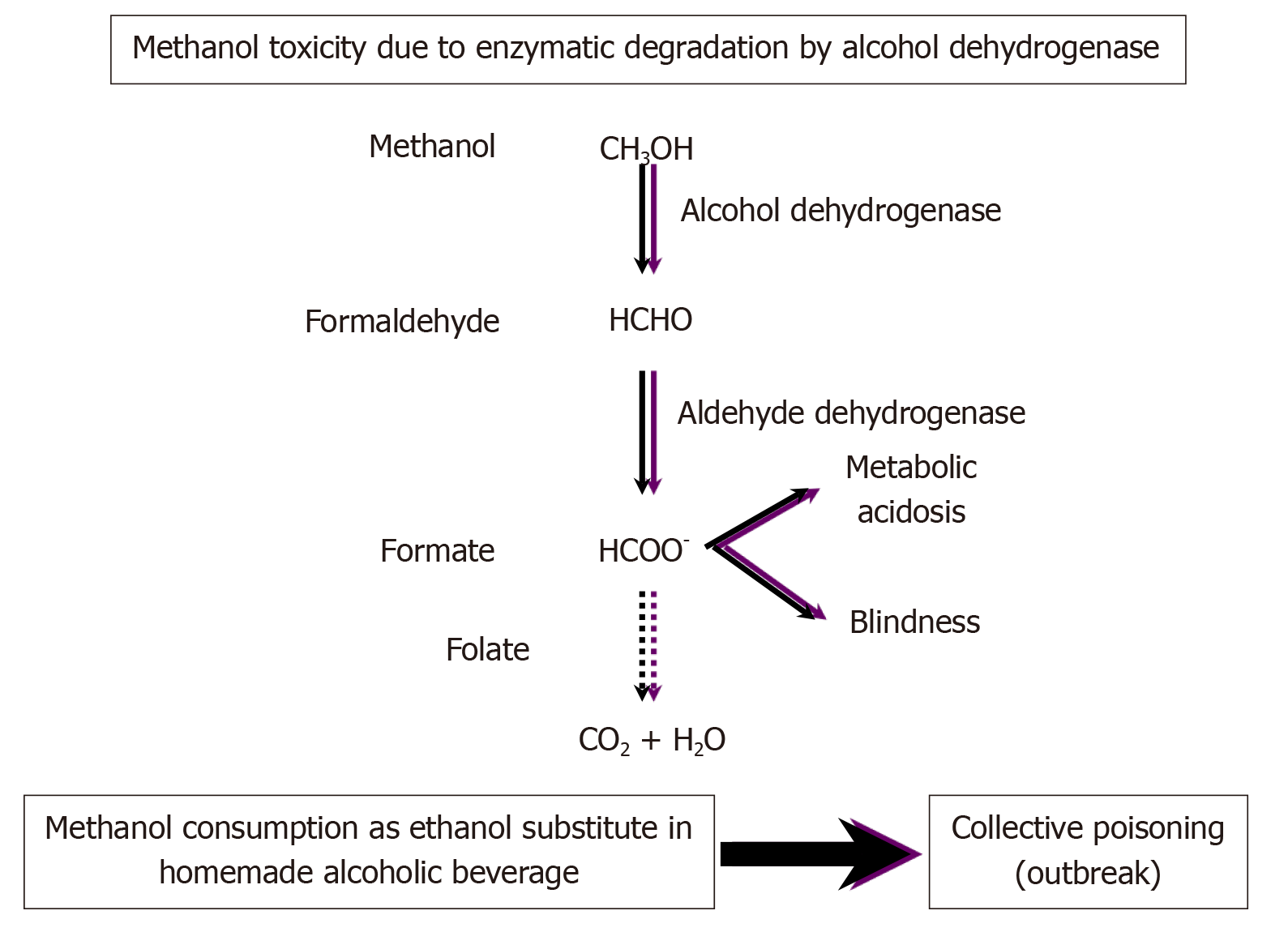

Methanol is included in many home chemicals, fluids, varnishes, stains and dyes. Toxicity results from its metabolism by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) to formic acid, which accumulates and results in metabolic acidosis and organ injuries (Figure 1)[1]. Small ingested amounts as little as 10 mL of pure methanol may be sufficient to cause life-threatening toxicity and permanent blindness[2].

Acute single-patient methanol poisonings are commonly reported while outbreaks occur sporadically, especially in countries with limited accessibility to ethanol due to unavailability or religious, cultural and economic reasons. Methanol is consumed accidentally as ethanol substitute in underground homemade alcoholic beverages[3-6]. Methanol poisoning outbreaks have also been reported in occidental countries resulting in hundreds of victims and deaths[7-10]. In such epidemics, providing effective therapy on time may be challenging, especially if the number of patients exceeds the availability of resources and in the absence of national guidelines to help physicians in charge. As dramatic illustration, a recent methanol poisoning outbreak in the northeast state of Assam in India has killed at least 154 people and left more than 200 people hospitalized after drinking an unregulated moonshine, known locally as "country-made liquor"[11]. Here, we report the outcome of a collective methanol intoxication that occurred in Cairo, Egypt in 2018 and discuss the different challenging issues from a public health perspective.

Five Ukrainian males were referred to our emergency department in Cairo, Egypt on May 28, 2018. The patients were transferred by ambulance and accompanied by an Arabic translator. Two patients were comatose, and three others drowsy with vomiting and headaches. Detailed history was taken from the conscious persons. All five patients were recently assigned to a local multinational factory in a neighboring area and lived there together in the same building. The day before, they tried to buy alcoholic beverages but did not know any local store. So, they prepared and ingested a homemade alcoholic beverage using bottles containing 70% ethanol disinfectant bought from a local pharmacy and fresh orange juice. They drank several glasses of this beverage during the day prior. Another sixth patient drank with them but refused to come to the hospital as he felt well. We requested from the translator to convince him to come as soon as possible. He came on the next day while presenting severe impairment in visual acuity, with perception limited to hand motion for the right eye and light for the left eye. All patients were promptly admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Vital signs, physical and biological parameters on admission as well as management and outcome data are presented in Table 1.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | ||

| Clinical parameters on admission | |||||||

| Age in yr | 41 | 47 | 41 | 46 | 42 | 42 | |

| Glasgow coma score | 3 | 3 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| Respiratory rate as /min | 32 | 30 | 26 | 29 | 23 | 18 | |

| Systolic/diastolic blood pressure in mmHg | 80/60 | 60/40 | 110/70 | 110/80 | 100/80 | 150/100 | |

| Pupils | Dilated | Dilated | Dilated | Dilated | Dilated | Dilated | |

| Repeated seizures | + | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Ophthalmological examination | - | Diminished visual acuity bilaterally with diminished visual field for follow-up | Diminished visual acuity bilaterally for follow-up | Diminished visual acuity bilaterally for follow-up | Diminished visual acuity bilaterally for follow-up | Hand motion by the right eye and light perception by the left eye | |

| Opthalmoscopy | Bilateral hyperemic swollen optic discs with flame-shaped shadow along superior arcade | Bilateral hyperemic optic discs with pale vassal rim | Bilateral hyperemic optic discs with peripapillary nerve fiber layer edema | Bilateral mild disc pallor and retinal edema | Bilateral pale swollen optic discs with superior and inferior retinal nerve fiber layer swelling | Bilateral disc pallor with normal retina | |

| Biological parameters on admission | |||||||

| Arterial pH | 6.80 | 6.80 | 7.18 | 7.03 | 7.07 | 7.36 | |

| HCO3- concentration in mmol/L | 4.2 | 4.5 | 9.7 | 8.2 | 4.3 | 20.9 | |

| PaCO2 in mmHg | 27 | 22 | 26 | 31 | 15 | 37 | |

| Serum creatinine in mg/dL | 1.1 | 1.6 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | |

| Blood urea nitrogen in mg/dL | 26 | 44 | 26 | 26 | 31 | 36 | |

| AST/ALT | 80/60 | 31/15 | 36/38 | 43/57 | 28/20 | 28/24 | |

| Hemoglobin in g/dL | 15.0 | 15.0 | 13.2 | 15.0 | 15.6 | 14.0 | |

| Platelets in G/L | 150 | 250 | 226 | 202 | 314 | 150 | |

| White blood cells in G/L | 8.1 | 22.7 | 13.6 | 8.3 | 14.3 | 6.1 | |

| Management | |||||||

| Sodium bicarbonates | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Thiamin at 400 mg/d, IV | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Leucovorin at 200 mg/d, IV | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Methylprednisolone at 400 mg/d, IV | + | + | - | - | + | + | |

| Diazepam at 30 mg/d, IV | + | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Hemodialysis 2-h session | One session | One session /d during 4 d | One session /d during 2 d | One session | One session | One session /d during 2 d | |

| Mechanical ventilation | + | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Vasopressor, norepinephrine | + | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Outcome | |||||||

| Outcome | Multiorgan failure and death | Disorientation, abnormal behavior, Diminished visual acuity | Full orientation, Pneumonia, Diminished visual acuity | Full orientation, Diminished visual acuity | Full orientation, Diminished visual acuity | Full orientation, Blindness | |

| ICU discharge | Day 1 | Day 7 | Day 3 | Day 3 | Day 3 | Day 5 | |

| Risk score, predicted risk of death1 | Risk E, 83% | Risk D, 50% | Risk A, 5% | Risk A, 5% | Risk A, 5% | Risk A, 5% | |

Based on history and presence of metabolic acidosis and visual impairment in all patients, methanol poisoning was suspected.

Due to the lack of readily available antidote and blood ethanol measurement in our laboratory, patients were treated with supportive care, vitamins (thiamin and leucoverin) and intermittent dialysis. Two hemodialysis devices were available in the ICU. Thus, 2-h sessions were successively provided to all patients starting with the most severely injured ones (Patient 1 to 5 then Patient 6 when admitted) and secondarily repeated on a daily basis if required by the metabolic disturbances.

One patient rapidly died from multiorgan failure a few hours after ICU admission. Due to persistent disorientation, brain magnetic resonance imaging was performed in Patient 2 showing bilateral, symmetrical sizable patchy areas of abnormal signals at cerebellar hemispheres and basal ganglia as well as bilateral and mainly subcortical frontal, parietal and occipital regions. Brain injuries elicited faintly bright to intermediate T2 and more bright fluid attenuation inversion recovery signals with restricted diffusion in diffusion-weighted imaging. The five survivors were discharged upon their request when possible to continue treatment and follow-up in their country. Before living our ICU, they gave their consent for the anonymous use of their data for research purposes.

Outbreaks of methanol poisoning occur frequently on a global basis and affect vulnerable populations[5]. The situation in Egypt is poorly known, likely with many cases and even outbreaks going unnoticed. Here, we described the features and outcome of six methanol-poisoned patients managed in Cairo, allowing us to acknowledge the limitations that influenced our therapeutic strategy and to review the main underlying public health issues that remain unsolved to date.

All six patients presented with severe metabolic acidosis, which is the most common disturbance in methanol intoxication due to the accumulation of formic acid[1,12]. All patients presented with visual disturbances, which is the only specific symptom of methanol poisoning. Visual disturbances are frequently reported in methanol poisoning, with approximately 30%-60% prevalence on hospital admission[9,13-17]. Ocular changes consist in bilateral retinal edema, hyperemia of the discs and blurring of the disc margins. Usually, optic atrophy is a late complication of methanol poisoning[12,13]. In our series, 1 patient developed almost complete blindness, probably due to his delayed admission and treatment in comparison to the others.

When methanol poisoning is suspected based on medical history, osmolal gap or anion gap metabolic acidosis, confirmation should be rapidly obtained with the measurement of blood methanol concentration[18,19]. However, if not readily available, osmolal gap has been reported to be a useful indicator for the presence of toxic alcohol to guide the treatment[19]. In our hospital, due to deficient regional resources, neither osmolality testing, anion gap measurement nor methanol leveling was readily available. Therefore, empirical therapy was immediately started based on the typical features attributed to methanol toxicity.

The full correction of metabolic acidosis and the rapid formate formation blockage and elimination are the cornerstones of management[2,12,20]. Ethanol, a competitive ADH substrate and fomepizole, a potent ADH inhibitor, are the two recommended antidotes with established effectiveness to reverse methanol toxicity[1,12,14,15,21]. Hemodialysis is effective to reverse rapidly metabolic acidosis and enhance methanol and formate elimination[2,12,20]. Leucoverin (folinic acid) is commonly administered due to its attributed effects to enhance formate metabolism in the monkey[22]. Our patients did not receive any antidote and were only treated with hemodialysis, folinic acid and supportive care. Fomepizole is not marketed in Egypt. Ethanol is not readily available at the bedside in our region; additionally, due to the non-availability of blood ethanol concentration measurement, its administration was estimated to be unsafe by the physicians in charge.

The recommended indications for extracorporeal treatment of methanol poisoning were revisited by the international Extracorporeal Treatment in Poisoning Work Group[20]. Recommendations included any of the following criteria being attributed to methanol: Coma, seizures, new vision deficits, metabolic acidosis with blood pH ≤ 7.15, persistent metabolic acidosis despite adequate supportive measures and antidotes and serum anion gap ≥ 24 mmol/L. Intermittent hemodialysis was recognized as the modality of choice, while continuous modalities were considered as acceptable alternatives. In our series, all patients presented at least one of these criteria and were therefore dialyzed. If available, serum methanol concentration should also be considered to indicate hemodialysis if ≥ 700 mg/L (21.8 mmol/L) in the context of fomepizole therapy; if ≥ 600 mg/L (18.7 mmol/L) in the context of ethanol treatment; and if ≥ 500 mg/L (15.6 mmol/L) in the absence of an ADH blocker[20]. In the absence of methanol concentration, the osmolal gap was estimated to inform the decision. In our situation, none of these biological parameters was available, and hemodialysis decision was undertaken based on the severity of acidosis and the presence of visual impairments on admission.

Although hemodialysis should be done in severely methanol-intoxicated patients, it may be readily unavailable in case of outbreak due to limited resources[23,24]. Selection of patients to perform hemodialysis should thus be prioritized on clinical indications (respiratory, neurological or visual symptoms or reduced kidney function) rather than on absolute methanol levels[12,20]. Contrary to conventional teaching, acidosis may occur only a few hours after ingestion, but this delay is prolonged in case of ethanol co-ingestion[23]. Here, the exact starting time and duration of drinking as well as the beverage composition remained unknown. Published data are insufficient to apply 200 mg/L (6.2 mmol/L) as treatment threshold in a non-acidotic patient arriving early for care. It is possible to offer prolonged ADH inhibition with fomepizole until hemodialysis can be performed, if necessary. Nevertheless, this approach should be balanced against the longer (approximately 52 h) methanol half-life with the antidote and need for extended hospitalization[14,21,25]. In patients without significant acidosis or ocular symptoms, treatment with ADH inhibition alone has been shown to be safe and is therefore a viable option if hemodialysis is not possible or methanol concentrations are not markedly elevated.

These international recommendations should reduce the allocation of resources to patients with less severe poisoning, so that extracorporeal treatments can be prioritized to those with greater need. Guidance on risk stratification of patients with severe methanol poisoning may be useful to help physicians in charge of mass casualty care[24]. Very recently, consensus statements were established on the approach to patients in a methanol poisoning outbreak, setting up international recommendations and a triage system that identifies patients most likely to benefit, so that they are prioritized in favor of those in whom treatment is futile or those with low toxicity exposures at that time[23]. A risk assessment score utilizing simple readily available parameters on patient admission exists, and it is based on a multicenter study that included observational data from several methanol poisoning outbreaks to help identify the patients associated with poor outcome (Table 2)[26]. Low pH (pH < 7.00), coma (Glasgow coma score < 8) and inadequate hyperventilation [PaCO2 ≥ 3.1 kPa (or 23 mmHg) in spite of arterial pH < 7.00] on admission were shown to be the strongest predictors of poor outcome after methanol poisoning. Interestingly, improved clinical outcome was more recently shown to be positively associated with out-of-hospital ethanol administration[27,28]. Therefore, conscious adults with suspected poisoning should be considered for administration of out-of-hospital ethanol to reduce morbidity and mortality. However, we acknowledge that such a recommendation has serious limitations in a Muslim country like Egypt.

| Risk group | Coma | Arterial pH | PaCO2 | Death risk |

| A | No | ≥ 7.00 | - | 5% |

| B | No | 6.74-6.99 | - | 10% |

| C | No | < 6.74 | - | 25% |

| D | Yes | 6.74-6.99 | < 3.07 | 50% |

| E | Yes | 6.74-6.99 | ≥ 3.07 | 83% |

| F | Yes | < 6.74 | - | 89% |

Outcome of methanol-induced blindness appears less predictable. However, improvement of optic nerve conductivity has been reported in more than 80% of the patients during the first years of follow-up[28]. Visual disturbances on admission and coma are significantly more prevalent in the patients with visual sequelae[16]. Although depth of acidosis at presentation is the strongest determinant of the final visual acuity, no other parameter at presentation including demographics, elapsed time to presentation, symptoms, neurological examination, arterial blood gas and brain computed tomography-scan findings was found able to identify transient versus permanent visual injuries in the initial disturbances[17,29]. In the recent Czech mass methanol outbreak, no association was found between visual sequelae and type of antidote administered, mode of hemodialysis or folate substitution, while only pre-hospital administration of ethanol seemed beneficial, if based on the follow-up evaluating the retinal nerve fibers layer by optical coherence tomography[16]. Intravenous high-dose methylprednisolone, alone[13] or in combination with intravenous erythropoietin[30], has been suggested to reverse methanol-induced ocular injuries provided the interval between methanol consumption and starting treatment is short like in our patients; but its definitive effectiveness remains to be proved.

One major issue in mass methanol poisoning is the rapid identification of the involved causative agent. Here, our investigations concluded that the suspected beverage was homemade with alcoholic disinfectant used for medicinal purposes and sold in most of local pharmacies, in bottles lacking pamphlet and use instructions. Data on the bottles written in Arabic only showed that they contained 70% ethanol and have to be kept away from children (Figure 2). It is probable that the absence of adequate information on the disinfectant bottles was misleading and confusing.

Prevention is also a major critical issue from a public health perspective and includes public education, constraining the public purchase of methanol-containing items and storing these items securely[7]. According to the Classification, Labeling and Packaging article 17 of the European Chemical Agency’s guidance of labeling and packaging, a substance and mixture classified as hazardous must bear a label including the following elements: (1) Name, address and telephone number of the supplier(s); (2) The nominal quantity of the substance or mixture in the package made available to the general public, unless this quantity is specified elsewhere on the package; and (3) Product identifiers; hazard pictograms, where applicable; the relevant signal word, where applicable; hazard statements, where applicable; and appropriate precautionary statements where applicable[31]. In addition, according to the Egyptian New Consumer Law 181/2018, the producer or supplier of any commodity must inform the consumer of all essential data about the product, including particularly its source, price, characteristics and all basic components in accordance with the Egyptian or international specifications standards. Clearly, the basic laws have not been respected in this situation.

This experience has alarmed us about the terrible consequences of shortages in staff, testing and treatment availability (antidote and extracorporeal treatments) in Egypt that may become challenging in a larger methanol poisoning outbreak. Poor knowledge of management of methanol poisoning among health workers and late diagnosis of the suspected cases may result in high case fatality. Increasing local competencies is crucial since mobilization of international teams in case of major outbreaks takes time[5]. A strategic plan should be in place in the rare event of an outbreak. Government health authorities should search for poisoned individuals who have not yet presented to hospitals. Joint effort between local health authorities and non-governmental organizations with the necessary infrastructure and emergency experience combined with provision of detailed and locally adapted treatment protocols and training is life-saving. Guidelines have to be rapidly disseminated by email alert systems or other internet-based services or hand-delivered when required in resource-limited regions.

Mass methanol poisoning with unpredictable risk assessment represents a major threat in developing countries with resource limitations like Egypt. In this local outbreak, immediate supply of supportive care and hemodialysis overcame the deficit in diagnostic testing and antidotes. This study brings attention to the risks due to sold products with no warnings or ingredients notice. Like the ongoing extended methanol poisoning outbreak in India, dramatic consequences are not impossible to exclude.

The authors would like to acknowledge Alison Good, Scotland, United Kingdom, for her helpful review of this manuscript.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country/Territory of origin: France

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tabaran F S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Kraut JA, Mullins ME. Toxic Alcohols. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:270-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Mégarbane B, Borron SW, Baud FJ. Current recommendations for treatment of severe toxic alcohol poisonings. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:189-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Aghababaeian H, Araghi Ahvazi L, Ostadtaghizadeh A. The Methanol Poisoning Outbreaks in Iran 2018. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019;54:128-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Onyekwere N, Nwadiuto I, Maleghemi S, Maduka O, Numbere TW, Akpuh N, Kanu E, Katchy I, Okeafor I. Methanol poisoning in South- South Nigeria: Reflections on the outbreak response. J Public Health Afr. 2018;9:748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rostrup M, Edwards JK, Abukalish M, Ezzabi M, Some D, Ritter H, Menge T, Abdelrahman A, Rootwelt R, Janssens B, Lind K, Paasma R, Hovda KE. The Methanol Poisoning Outbreaks in Libya 2013 and Kenya 2014. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Nikfarjam A, Mirafzal A, Saberinia A, Nasehi AA, Masoumi Asl H, Memaryan N. Methanol mass poisoning in Iran: role of case finding in outbreak management. J Public Health (Oxf). 2015;37:354-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Collister D, Duff G, Palatnick W, Komenda P, Tangri N, Hingwala J. A Methanol Intoxication Outbreak From Recreational Ingestion of Fracking Fluid. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69:696-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zakharov S, Pelclova D, Urban P, Navratil T, Diblik P, Kuthan P, Hubacek JA, Miovsky M, Klempir J, Vaneckova M, Seidl Z, Pilin A, Fenclova Z, Petrik V, Kotikova K, Nurieva O, Ridzon P, Rulisek J, Komarc M, Hovda KE. Czech mass methanol outbreak 2012: epidemiology, challenges and clinical features. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:1013-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Paasma R, Hovda KE, Tikkerberi A, Jacobsen D. Methanol mass poisoning in Estonia: outbreak in 154 patients. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2007;45:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hovda KE, Hunderi OH, Tafjord AB, Dunlop O, Rudberg N, Jacobsen D. Methanol outbreak in Norway 2002-2004: epidemiology, clinical features and prognostic signs. J Intern Med. 2005;258:181-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gupta S, Guy J, Humayun H, CNN. Toxic moonshine kills 154 people and leaves hundreds hospitalized in India. [published 25 February 2019]. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/02/24/asia/india-alcohol-poisoning/index.html. |

| 12. | Barceloux DG, Bond GR, Krenzelok EP, Cooper H, Vale JA; American Academy of Clinical Toxicology Ad Hoc Committee on the Treatment Guidelines for Methanol Poisoning. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2002;40:415-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in RCA: 358] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sodhi PK, Goyal JL, Mehta DK. Methanol-induced optic neuropathy: treatment with intravenous high dose steroids. Int J Clin Pract. 2001;55:599-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mégarbane B, Borron SW, Trout H, Hantson P, Jaeger A, Krencker E, Bismuth C, Baud FJ. Treatment of acute methanol poisoning with fomepizole. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1370-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Brent J, McMartin K, Phillips S, Aaron C, Kulig K; Methylpyrazole for Toxic Alcohols Study Group. Fomepizole for the treatment of methanol poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:424-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zakharov S, Pelclova D, Diblik P, Urban P, Kuthan P, Nurieva O, Kotikova K, Navratil T, Komarc M, Belacek J, Seidl Z, Vaneckova M, Hubacek JA, Bezdicek O, Klempir J, Yurchenko M, Ruzicka E, Miovsky M, Janikova B, Hovda KE. Long-term visual damage after acute methanol poisonings: Longitudinal cross-sectional study in 50 patients. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2015;53:884-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Desai T, Sudhalkar A, Vyas U, Khamar B. Methanol poisoning: predictors of visual outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kraut JA. Diagnosis of toxic alcohols: limitations of present methods. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2015;53:589-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hovda KE, Hunderi OH, Rudberg N, Froyshov S, Jacobsen D. Anion and osmolal gaps in the diagnosis of methanol poisoning: clinical study in 28 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1842-1846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Roberts DM, Yates C, Megarbane B, Winchester JF, Maclaren R, Gosselin S, Nolin TD, Lavergne V, Hoffman RS, Ghannoum M; EXTRIP Work Group. Recommendations for the role of extracorporeal treatments in the management of acute methanol poisoning: a systematic review and consensus statement. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:461-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Brent J. Fomepizole for ethylene glycol and methanol poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2216-2223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | McMartin KE, Martin-Amat G, Makar AB, Tephly TR. Methanol poisoning. V. Role of formate metabolism in the monkey. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;201:564-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Zamani N, Roberts DM, Brent J, McMartin K, Aaron C, Eddleston M, Dargan PI, Olson K, Nelson L, Bhalla A, Hantson P, Jacobsen D, Megarbane B, Balali-Mood M, Buckley NA, Zakharov S, Paasma R, Jarwani B, Mirafzal A, Salek T, Hovda KE. Consensus statements on the approach to patients in a methanol poisoning outbreak. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:1129-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Roberts DM, Hoffman RS, Gosselin S, Megarbane B, Yates C, Ghannoum M. The authors reply. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:e211-e212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hovda KE, Jacobsen D. Expert opinion: fomepizole may ameliorate the need for hemodialysis in methanol poisoning. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2008;27:539-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sanaei-Zadeh H, Zamani N, Shadnia S. Outcomes of visual disturbances after methanol poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:102-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zakharov S, Pelclova D, Urban P, Navratil T, Nurieva O, Kotikova K, Diblik P, Kurcova I, Belacek J, Komarc M, Eddleston M, Hovda KE. Use of Out-of-Hospital Ethanol Administration to Improve Outcome in Mass Methanol Outbreaks. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68:52-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nurieva O, Hubacek JA, Urban P, Hlusicka J, Diblik P, Kuthan P, Sklenka P, Meliska M, Bydzovsky J, Heissigerova J, Kotikova K, Navratil T, Komarc M, Seidl Z, Vaneckova M, Vojtova L, Zakharov S. Clinical and genetic determinants of chronic visual pathway changes after methanol - induced optic neuropathy: four-year follow-up study. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019;57:387-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Paasma R, Hovda KE, Hassanian-Moghaddam H, Brahmi N, Afshari R, Sandvik L, Jacobsen D. Risk factors related to poor outcome after methanol poisoning and the relation between outcome and antidotes--a multicenter study. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012;50:823-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pakdel F, Sanjari MS, Naderi A, Pirmarzdashti N, Haghighi A, Kashkouli MB. Erythropoietin in Treatment of Methanol Optic Neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2018;38:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | European Chemical Agency’s guidance of labeling and packaging. [cited 6 April 2020]. Available from: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/23036412/clp_labelling_en.pdf/89628d94-573a-4024-86cc-0b4052a74d65. |