Published online Feb 4, 2017. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v6.i1.85

Peer-review started: July 13, 2016

First decision: September 2, 2016

Revised: October 26, 2016

Accepted: November 16, 2016

Article in press: November 17, 2016

Published online: February 4, 2017

Processing time: 193 Days and 21 Hours

We report a case of virus-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) treated with parenteral vitamin C in a patient testing positive for enterovirus/rhinovirus on viral screening. This report outlines the first use of high dose intravenous vitamin C as an interventional therapy for ARDS, resulting from enterovirus/rhinovirus respiratory infection. From very significant preclinical research performed at Virginia Commonwealth University with vitamin C and with the very positive results of a previously performed phase I safety trial infusing high dose vitamin C intravenously into patients with severe sepsis, we reasoned that infusing identical dosing to a patient with ARDS from viral infection would be therapeutic. We report here the case of a 20-year-old, previously healthy, female who contracted respiratory enterovirus/rhinovirus infection that led to acute lung injury and rapidly to ARDS. She contracted the infection in central Italy while on an 8-d spring break from college. During a return flight to the United States, she developed increasing dyspnea and hypoxemia that rapidly developed into acute lung injury that led to ARDS. When support with mechanical ventilation failed, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was initiated. Twelve hours following ECMO initiation, high dose intravenous vitamin C was begun. The patient’s recovery was rapid. ECMO and mechanical ventilation were discontinued by day-7 and the patient recovered with no long-term ARDS sequelae. Infusing high dose intravenous vitamin C into this patient with virus-induced ARDS was associated with rapid resolution of lung injury with no evidence of post-ARDS fibroproliferative sequelae. Intravenous vitamin C as a treatment for ARDS may open a new era of therapy for ARDS from many causes.

Core tip: Enterovirus/rhinovirus has been reported to cause devastating acute lung injury. We report here the first use of high dose intravenous vitamin C to attenuate the acute respiratory distress syndrome that was caused by this viral infection. We have previously reported that vitamin C used in this interventional fashion is a potent anti-inflammatory agent.

- Citation: Fowler III AA, Kim C, Lepler L, Malhotra R, Debesa O, Natarajan R, Fisher BJ, Syed A, DeWilde C, Priday A, Kasirajan V. Intravenous vitamin C as adjunctive therapy for enterovirus/rhinovirus induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. World J Crit Care Med 2017; 6(1): 85-90

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v6/i1/85.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v6.i1.85

Viral diseases can produce the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)[1]. Pandemic viruses are the most common viruses that produce lung injury. Influenza viruses and coronaviruses (e.g., H5N1, H1N1 2009, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus) are potentially lethal pathogens known to produce lung injury and death from ARDS[2-5]. At the tissue level, lung injury results from increased permeability of the alveolar-capillary membrane that leads to hypoxia, pulmonary edema, and intense cellular infiltration, particularly neutrophilic infiltration. The exact pathogenesis of virus-induced ARDS is slowly becoming understood. Unlike the “cytokine storm” occurring in bacterial sepsis that leads to up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines [e.g., interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-8, IL-6] and generation of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species in the vascular space, viruses such as the influenza virus target alveolar epithelium, disabling sodium pump activity, damaging tight junctions, and inducing cell death in infected cells. Cytokines produced by virally infected alveolar epithelial cells activate adjacent lung capillary endothelial cells which then leads to neutrophil infiltration. Subsequent production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by infiltrating neutrophils further damages lung barrier function[1]. Apart from pandemic viruses other viruses, are increasingly reported to produce severe ARDS. While most of the approximately 100 strains of enterovirus primarily infect the gastrointestinal tract, enterovirus-D68 (EV-D68) has tropism for the respiratory tract. EV-D68 produces acute respiratory disease ranging from mild upper respiratory tract symptoms to severe pneumonia and lung injury as in the case we describe here. In an outpatient setting, EV-D68 disease has manifested most commonly among persons younger than 20 years and adults aged 50-59 years[6]. In August 2014, EV-D68 emerged as a cause of severe respiratory infections with hospitals in Illinois and Missouri reporting an increased incidence of rhinovirus and enterovirus infection[7]. In this report, 30 of 36 isolates from the nasopharyngeal secretions of patients with severe respiratory illness were identified as EV-D68. Following these reports, an unusually high number of patients with severe respiratory illness were admitted to these facilities, presumably with EV-D68 infection. Enterovirus-D68 leading to ARDS has been reported in China, Japan, and in the United States[8-11]. The report by Farrell et al[11], describes a previously healthy 26-year-old woman who developed severe ARDS following an enterovirus-D68 infection. Despite all critical care support measures, the patient required protracted mechanical ventilation for 32-d, necessitating tracheostomy and endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. She was discharged alive 55 d following admission. Enterovirus and rhinovirus were recovered from the respiratory secretions of the patient we report here. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was rapidly required in our patient’s care following failure of conventional mechanical ventilation. The patient reported by Farrell et al[11] is the full extent of support required for patients with ARDS who ultimately develop a fibroproliferative course as described by Burnham et al[12]. Karhu et al[13] and Choi et al[14] recently reported finding rhinovirus as the etiology of severe community acquired pneumonia and respiratory failure in mechanically ventilated adults who had a proven viral etiology of respiratory failure.

We report here the first application of high dose intravenous vitamin C employed as an interventional drug treatment for virus-induced ARDS. Very few studies in critically ill patients with ARDS have reported the use of intravenous vitamin C. The use of vitamin C to treat lung injury is still investigational. Nathens et al[15] infused ascorbic acid at 1 g every 8 h combined with oral vitamin E for 28 d in 594 surgically critically ill patients and found a significantly lower incidence of acute lung injury and multiple organ failure. Tanaka et al[16] infused ascorbic acid continuously at 66 mg/kg per hour for the first 24 h in patients with greater than 50% surface area burns and showed significantly reduced burn capillary permeability. A single report (published as abstract only) of a clinical study of large intravenous doses of ascorbic acid, and other antioxidants (tocopherol, N-acetyl-cysteine, selenium), in patients with established ARDS showed reduction in mortality of 50%[17]. Clinical protocols currently in use for hospitalized septic patients fail to normalize ascorbic acid levels. Vitamin C dosages utilized in the treatment of the patient we describe in this case report arose from our previous human studies, infusing high dose intravenous vitamin C into critically ill patients with severe sepsis[18] and in our preclinical studies[19-21]. Our work thus far shows vitamin C to exert potent “pleotropic effects” when used as described in this report. We showed that septic patients receiving high dose intravenous vitamin C exhibit significant reduction in multiple organ injury and reduced inflammatory biomarker levels[18]. Our preclinical work in septic lung-injured animals shows that vitamin C down-regulates pro-inflammatory genes that are driven by transcription factor NF-κB. Furthermore, vitamin C significantly increases alveolar fluid clearance in septic lung-injured animals[21]. Finally, infused vitamin C’s capability to down-regulate liberated reactive oxygen and nitrogen species appears to be critical for attenuating lung injury[22].

A 20-year-old white female presented to urgent care with 24 h of increasing dyspnea after returning from a 7-d trip to Italy. While in Italy she was exposed to several members of the family with whom she was visiting who had symptoms of upper tract respiratory infection. One family member had recently traveled to Morocco. While in Italy, the patient had visited a buffalo farm and ate unpasteurized cheese. There were no other unusual exposures. She noted cough and yellow sputum for 3 d with intermittent fever and night sweats.

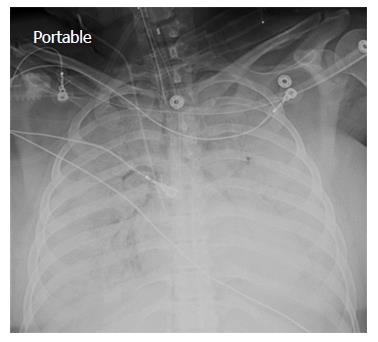

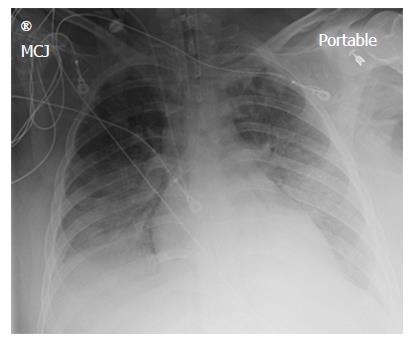

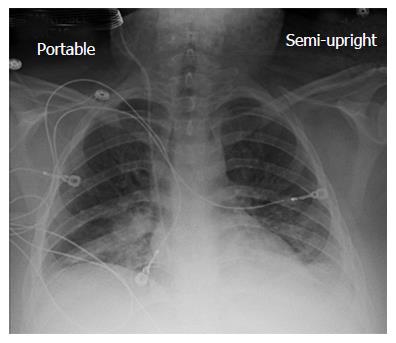

A chest X-ray revealed diffuse bilateral opacities (Figure 1). Arterial blood gas testing revealed severe hypoxemia while receiving 100% oxygen by non-rebreather mask. Antibiotics were initiated and she was admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) with a diagnosis of community acquired pneumonia. She denied GI symptoms, rash or arthralgia. She denied any history of thromboembolic disease, chest or leg pain or swelling. Her only medication was oral contraceptive for migraines associated with her menstrual cycle. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation failed to support hypoxemic respiratory failure and intubation was required on hospital day 3. An echocardiogram revealed normal cardiac function. Respiratory cultures were negative, but a molecular detection viral respiratory panel was positive for enterovirus/rhinovirus (FilmArray, BioFire Diagnostics, LLC, Salt Lake City, Utah). Despite high PEEP and low tidal volume ventilation, hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 = 75) and hypercapnia remained severe. Chest imaging on hospital day 3 revealed dense bilateral opacities with central air bronchograms (Figure 2). Due to failure of conventional ventilatory strategies, veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was initiated on hospital day 3. Low tidal volume assist-control, pressure-control ventilatory strategy was continued. Vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam and levofloxacin started at ICU admission were continued. High-dose intravenous vitamin C (200 mg/kg per 24 h) was initiated on ECMO day 1 with the total daily vitamin C dosage divided equally into four doses and infused every 6 h. AP chest X-ray imaging on ECMO day 2 following institution of vitamin C infusion revealed significant improvement in bilateral lung opacities (Figure 3). Given the patient’s hemodynamic instability and vasopressor requirements, the critical care physician staff and nursing staff were very careful to keep the patient’s intake and output fluid balance even, being careful not to volume load a patient who was suffering from permeability pulmonary edema. Bronchoscopy on ECMO day 3 was negative for bacterial or fungal respiratory pathogens. Histoplasma, Blastomyces, Aspergillus, and Legionella antigen studies were negative. Furosemide was used to achieve a daily negative fluid balance. Daily chest imaging with AP chest X-rays documented continued resolution of bilateral opacities. Importantly, lung gas exchange significantly improved following institution of vitamin C infusions. Chest imaging on ECMO day 6 revealed significant further reduction in lung opacities. ECMO decannulation and extubation from ventilation occurred on ECMO day 7 (Figure 4). Vitamin C dosing was continued while the patient remained on ECMO. Vitamin C dosing was reduced by half (100 mg/kg per 24 h) for one day following decannulation from ECMO then reduced by half again (50 mg/kg per 24 h) for an additional day. Post-extubation the patient required 4 L/min nasal oxygen for 48 h and then was discharged home on room air. She was discharged home on hospital day 12. Although we did not quantify the plasma ascorbic acid levels in the patient we report here, we have previously reported that critically ill patients with severe sepsis treated with the identical vitamin C infusion protocol achieved plasma ascorbic acid levels of 3.2 mmol, values which are 60 fold higher than normal plasma ascorbic acid levels[18].

In conclusion, we report here the first use of vitamin C as an interventional drug to attenuate lung injury produced by viral infection. The patient described here was discharged home 12 d following hospitalization, requiring no oxygen therapy. Follow-up exam at 1 mo following the patient’s initial hospitalization revealed her to have completely recovered. Figure 5 displays her follow-up chest X-ray film. Importantly, it should be noted that this is a single case report. The role of Vitamin C in this patient’s recovery is not certain, and clearly additional investigation will be required before this can be recommended as a therapy for ARDS.

The authors are grateful to Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center in Richmond, Virginia, the Divisions of Medical, Surgical, and Anesthesia Critical Care Medicine, Richmond, Virginia, United States. The pre-clinical work that led up to the use of vitamin C as an interventional agent in humans was supported by the Aubrey Sage McFarlane acute lung injury fund, the VCU Johnson Center for Critical Care and Pulmonary Research.

A 20-year-old female with no significant medical history presented with acute respiratory failure following a spring break in central Italy. While in Italy she was exposed to a sick contact who was a member of the family she was staying with.

The clinical diagnosis of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in this case was established by the extent of respiratory failure present, the radiographic findings, and the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenator support required. The patient’s exposure to the sick contact in Italy suggested the diagnosis of a viral etiology.

ARDS, viral pneumonia, sepsis from unknown etiology.

The diagnosis of the etiology of the patient’s respiratory failure was obtained by a panel that uses real-time polymerase chain reaction technology to identify respiratory viral pathogens. FilmArray Respiratory panel is manufactured by BioFire Diagnostics, LLC, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Standard Anterior-Posterior chest X-ray films confirmed the diagnosis of ARDS.

No lung tissue was obtained from the patient. The diagnosis of ARDS was established by the extent of respiratory failure and the imaging required during the patients hospital stay.

In this case report, the authors describe the first use of high dosage intravenous vitamin C as adjunctive therapy for viral induced ARDS.

At this point in time, there are no other case reports specifically referencing vitamin C as a treatment for ARDS. The authors have previously reported (ref. [18]) the use of high dose vitamin C as an adjunctive therapy for severe sepsis. Many patients in that trial likely could be considered to have had ARDS.

For many years multiple investigators have conducted clinical treatment trials, searching for effective therapies to assist in the treatment for ARDS. In this case report, the authors may have shed new light on a treatment which may ultimately be effective. The successful outcome described in this case report would suggest that larger trials must be conducted with high dosage intravenous vitamin C.

This is an interesting report of use of high dose intravenous vitamin C in ARDS.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Critical care medicine

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Boucek CD, Inchauspe AA, Riutta AA, Willms DC S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Short KR, Kroeze EJ, Fouchier RA, Kuiken T. Pathogenesis of influenza-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:57-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4030] [Cited by in RCA: 4029] [Article Influence: 309.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Guery B, Poissy J, el Mansouf L, Séjourné C, Ettahar N, Lemaire X, Vuotto F, Goffard A, Behillil S, Enouf V. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet. 2013;381:2265-2272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Drosten C, Seilmaier M, Corman VM, Hartmann W, Scheible G, Sack S, Guggemos W, Kallies R, Muth D, Junglen S. Clinical features and virological analysis of a case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:745-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | de Jong MD, Simmons CP, Thanh TT, Hien VM, Smith GJ, Chau TN, Hoang DM, Chau NV, Khanh TH, Dong VC. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat Med. 2006;12:1203-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1545] [Cited by in RCA: 1490] [Article Influence: 78.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Meijer A, van der Sanden S, Snijders BE, Jaramillo-Gutierrez G, Bont L, van der Ent CK, Overduin P, Jenny SL, Jusic E, van der Avoort HG. Emergence and epidemic occurrence of enterovirus 68 respiratory infections in The Netherlands in 2010. Virology. 2012;423:49-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Midgley CM, Jackson MA, Selvarangan R, Turabelidze G, Obringer E, Johnson D, Giles BL, Patel A, Echols F, Oberste MS. Severe respiratory illness associated with enterovirus D68 - Missouri and Illinois, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:798-799. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Xiang Z, Gonzalez R, Wang Z, Ren L, Xiao Y, Li J, Li Y, Vernet G, Paranhos-Baccalà G, Jin Q. Coxsackievirus A21, enterovirus 68, and acute respiratory tract infection, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:821-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang T, Ren L, Luo M, Li A, Gong C, Chen M, Yu X, Wu J, Deng Y, Huang F. Enterovirus D68-associated severe pneumonia, China, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:916-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kaida A, Kubo H, Sekiguchi J, Kohdera U, Togawa M, Shiomi M, Nishigaki T, Iritani N. Enterovirus 68 in children with acute respiratory tract infections, Osaka, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1494-1497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Farrell JJ, Ikladios O, Wylie KM, O’Rourke LM, Lowery KS, Cromwell JS, Wylie TN, Melendez EL, Makhoul Y, Sampath R. Enterovirus D68-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome in adult, United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:914-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Riches DW, Moss M, Downey GP. The fibroproliferative response in acute respiratory distress syndrome: mechanisms and clinical significance. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:276-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karhu J, Ala-Kokko TI, Vuorinen T, Ohtonen P, Syrjälä H. Lower respiratory tract virus findings in mechanically ventilated patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Choi SH, Hong SB, Ko GB, Lee Y, Park HJ, Park SY, Moon SM, Cho OH, Park KH, Chong YP. Viral infection in patients with severe pneumonia requiring intensive care unit admission. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nathens AB, Neff MJ, Jurkovich GJ, Klotz P, Farver K, Ruzinski JT, Radella F, Garcia I, Maier RV. Randomized, prospective trial of antioxidant supplementation in critically ill surgical patients. Ann Surg. 2002;236:814-822. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Tanaka H, Matsuda T, Miyagantani Y, Yukioka T, Matsuda H, Shimazaki S. Reduction of resuscitation fluid volumes in severely burned patients using ascorbic acid administration: a randomized, prospective study. Arch Surg. 2000;135:326-331. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sawyer MAJ, Mike JJ, Chavin K. Antioxidant therapy and survival in ARDS (abstract). Crit Care Med. 1989;17:S153. |

| 18. | Fowler AA, Syed AA, Knowlson S, Sculthorpe R, Farthing D, DeWilde C, Farthing CA, Larus TL, Martin E, Brophy DF. Phase I safety trial of intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with severe sepsis. J Transl Med. 2014;12:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fisher BJ, Seropian IM, Kraskauskas D, Thakkar JN, Voelkel NF, Fowler AA, Natarajan R. Ascorbic acid attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1454-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fisher BJ, Kraskauskas D, Martin EJ, Farkas D, Puri P, Massey HD, Idowu MO, Brophy DF, Voelkel NF, Fowler AA. Attenuation of sepsis-induced organ injury in mice by vitamin C. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:825-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fisher BJ, Kraskauskas D, Martin EJ, Farkas D, Wegelin JA, Brophy D, Ward KR, Voelkel NF, Fowler AA, Natarajan R. Mechanisms of attenuation of abdominal sepsis induced acute lung injury by ascorbic acid. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L20-L32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Berger MM, Oudemans-van Straaten HM. Vitamin C supplementation in the critically ill patient. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18:193-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |