INTRODUCTION

A shock is a form of acute circulatory failure associated with an inequality between systemic oxygen delivery (DO2) and oxygen consumption (VO2), which result in tissue hypoxia[1]. Early recognition and adequate resuscitation of tissue hypoperfusion are of particular importance in the management of septic shock to avoid the development of tissue hypoxia and multi-organ failure. Assessment of mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) from a pulmonary artery catheter has been proposed as an indirect marker of global tissue oxygenation[2]. SvO2 reflects the balance between oxygen demand and supply. A low SvO2 represents a high oxygen extraction (O2ER) in order to maintain aerobic metabolism and VO2 constant in response to an acute decrease in DO2. However, when DO2 drops under a critical value, O2ER is no longer capable of upholding VO2, and global tissue hypoxia appears, as indicated by the occurrence of lactic acidosis[3-5].

Since the assessment of central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) can be achieved more easily, and is less risky than from pulmonary artery catheter, it would be useful if ScvO2 could function as an accurate reflection of SvO2. In fact, SvO2 is not similar to ScvO2 because the latter primarily reflects the oxygenation of the upper side of the body. In normal patients, ScvO2 is lower than SvO2 by about 2% to 3%, largely because of the less rate of oxygen extraction by the kidneys[6]. In shock state, the absolute value of ScvO2 was more often reported to be higher than ScvO2, probably due to the oxygen extraction increases in splanchnic and renal tissues[7-11]. This suggests that the existence of a decreased ScvO2 implies an even smaller SvO2. Because of the lack of agreement regarding absolute values, some authors questioned the clinical utility of ScvO2[12,13]. However, despite absolute values differ, trends in ScvO2 closely mirror trends in SvO2[8,9], suggesting that monitoring ScvO2 makes sense in critically ill patients.

It has been shown that an early hemodynamic optimization using a resuscitation bundle aimed at increasing ScvO2 > 70% was related to an important reduction in septic shock mortality[14]. Since that, monitoring ScvO2 has become widely recommended[1,14,15]. Recently, three large multicenter studies[16-18] failed to demonstrate any benefits of the early goal-directed therapy approach. Nevertheless, the design of these trials was not to answer the question of whether targeting an ScvO2 > 70% was effective. Also, in these studies, the mean baseline ScvO2 values were already above 70%. Thus, these findings do not indicate that clinicians should stop monitoring ScvO2 and adjust DO2 by optimizing ScvO2 levels, particularly in septic shock patients with low ScvO2, who are at the highest risk of death[19].

On the other hand, normalization of ScvO2 does not rule out persistent tissue hypoperfusion and does not preclude evolution to multi-organ dysfunction and death[20]. The obvious limitation of ScvO2 is that normal/high values cannot distinguish if DO2 is sufficient or in excess to demand. In septic conditions, normal/high ScvO2 values might be due to the heterogeneity of the microcirculation that generates capillary shunting and/or mitochondrial damage responsible of disturbances in tissue oxygen extraction. Because ScvO2 is measured downstream from tissues, when a given tissue receives inadequate DO2, the resulting low local oxygen venous saturations may be “masked” by admixture with highly saturated venous blood from tissues with better perfusion and DO2, resulting overall in normal or even high ScvO2. Although ScvO2 may thus not miss any global DO2 dysfunction, it may stay “blind” to local perfusion disturbances, which exist in abundance in sepsis due to damaged microcirculation. Indeed, high ScvO2 values have been associated with increased mortality in septic shock patients[21,22]. Thus, in some circumstances the use of ScvO2 might erroneously drive a clinician to conclude that the physiologic state of the patient has ameliorated when, in fact, it may not have improved.

Lactate has also been proposed as a resuscitation endpoint[23,24]. However, no benefits have been observed for lactate decrease-guided therapy over resuscitation guided by ScvO2 in septic shock patients[25]. Moreover, given the nonspecific nature of lactate level elevation, hyperlactatemia alone is not a discriminatory factor in establishing the source of the circulatory failure. Hence, additional circulatory parameters such as the venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide tension difference are needed to identify patients with septic shock who presently may still insufficiently reanimated, especially when ScvO2 values are normal/high in the context of hyperlactatemia. The purpose of this review is to discuss the physiologic background and the potential clinical usefulness of the venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide tension difference in septic shock.

PHYSIOLOGICAL BACKGROUND

CO2 transport in the blood

CO2 is transported in the blood in three figures[26]: Dissolved, in combination with proteins as carbamino compounds, and as bicarbonate. Physically dissolved CO2 is a function of CO2 solubility in blood, which is about 20 times that of oxygen (O2); therefore, considerably more CO2 than O2 is present in simple solution at equal partial pressures. However, dissolved CO2 shares only around 5% of the whole CO2 concentration in arterial blood.

Carbamino compounds comprise the second form of CO2 in the blood. These compounds occur when CO2 combines with terminal amine groups in blood proteins, especially with the globin of hemoglobin. However, this chemical combination between CO2 and hemoglobin is much less important than haemoglobin-O2 binding, so carbamino compounds comprise only 5% of the total CO2 in the arterial blood.

The bicarbonate ion (HCO3–) is the most significant form of the CO2 carriage in the blood. CO2 combines with water (H2O) to form carbonic acid (H2CO3), and this dissociates to HCO3– and hydrogen ion (H+): CO2 + H2O = H2CO3 = HCO3– + H+. Carbonic anhydrase is the enzyme that catalyzes the first reaction, making it almost instantaneous. Carbonic anhydrase occurs mainly in red blood cells (RBC), but it also occurs on pulmonary capillary endothelial cells, and it accelerates the reaction in plasma in the lungs. The uncatalyzed reaction will occur in plasma, but at a much slower rate. The second reaction happens immediately inside RBC and does not require any enzyme. The H2CO3 dissociates to H+ and HCO3–, and the H+ is buffered primarily by hemoglobin while the excess HCO3– is transported out the RBC into plasma by an electrically neutral bicarbonate-chloride exchanger. The fast conversion of CO2 to HCO3– results in nearly 90% of the CO2 in arterial blood being transported in that manner.

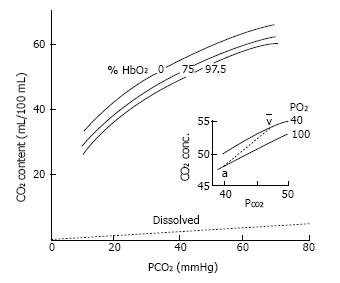

Hemoglobin-O2 saturation is the major factor affecting the capacity of hemoglobin to fix CO2 (Haldane effect). Consequently, CO2 concentration increases when blood is deoxygenated, or CO2 concentration diminishes when blood is oxygenated, at any assumed carbon dioxide tension (PCO2)[26] (Figure 1). H+ ions from CO2 can be deemed as competing with O2 for hemoglobin binding. Accordingly, rising oxygen reduces the affinity of hemoglobin for H+ and blood CO2 concentration (Haldane effect). The physiological assets of the Haldane effect are that it promotes removing of CO2 in the lungs when blood is oxygenated and CO2 filling in the blood when oxygen is delivered to tissues. Additionally, the Haldane effect leads to a sharper physiologic CO2 blood equilibrium curve that has the physiologic interest of rising CO2 concentration differences for a given PCO2 difference.

Figure 1 CO2 dissociation curve.

CO2 content (mL/100 mL) vs CO2 partial tension (PCO2). Differences between the curves result in higher CO2 content in the blood, and smaller PCO2 differences between arterial and venous blood. Hemoglobin-O2 saturation affects the position of the CO2 dissociation curve (Haldane effect).

CO2 is rapidly excreted from the circulation by the lungs by passive diffusion from the capillaries to the alveoli, and its production approximately matches excretion.

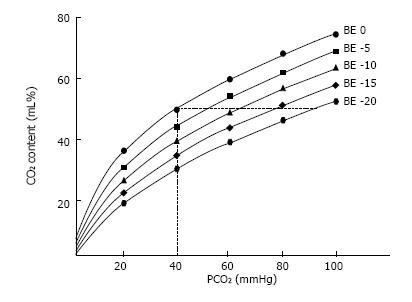

The relationship between PCO2 and the total blood CO2 content (CCO2) is curvilinear even though more linear than the oxygen dissociation curve[26]. Oxygen saturation, hematocrit, temperature, and the degree of metabolic acidosis influence the PCO2/CCO2 relationship[26]. Hence, for a given value of CCO2, PCO2 is higher in the case of metabolic acidosis than in the case of normal pH (Figure 2).

Figure 2 CO2 dissociation curve.

CO2 content (mL/100 mL) vs CO2 partial tension (PCO2). Each curve is described at constant base excess (BE). As displayed, for the same CO2 content, changing the BE results in a great change in PCO2.

Determinant of venous-to-arterial CO2 tension difference

The venous-to-arterial CO2 tension difference [P (v-a) CO2] is the gradient between PCO2 in mixed venous blood (PvCO2) and PCO2 in arterial blood (PaCO2): P (v-a) CO2 = PvCO2 -PaCO2; PvCO2 and PaCO2 are partial pressures of the dissolved CO2 in the mixed venous and arterial blood, respectively.

The application of Fick equation to CO2 shows that the CO2 elimination (identical to CO2 generation in a stable condition) equals the product of the difference between mixed venous blood CO2 content (CvCO2) and arterial blood CO2 content (CaCO2) and cardiac output: Total CO2 production (VCO2) = cardiac output × (CvCO2 - CaCO2). In spite of a global curvilinear shape of the relation between PCO2 and the total CCO2, there is a rather linear association between CCO2 and PCO2 over the general physiological range of CO2 content so that CCO2 can be substituted by PCO2 (PCO2 = k × CCO2)[27-29]. Therefore, VCO2 can be calculated from a modified Fick equation as: VCO2 = cardiac output × k × P (v-a) CO2 so that P (v-a) CO2 = k × VCO2/cardiac output, where k is the pseudo-linear coefficient supposed to be constant in physiological states[27]. Therefore, P (v-a) CO2 would be linearly linked to CO2 generation and inversely associated to cardiac output. Under normal conditions, P (v-a) CO2 values range between 2 and 6 mmHg[30].

Influence of CO2 production on P (v-a) CO2

Aerobic CO2 production: Oxidative phosphorylation proceeds with the formation of energy-laden molecules, CO2 and water. Total CO2 production is directly related to VO2: VCO2 = R × VO2, where R is the respiratory quotient varying among 0.7 and 1.0 according to the energy intake. Under circumstances of important carbohydrate consumption, R becomes close to 1.0. Thus, CO2 generation should increase either with elevated oxidative metabolism or for a constant VO2 when a balanced alimentation regime is substituted by a high carbohydrate consumption regime[31]. Under both situations of increased VCO2, P (v-a) CO2 should increase unless cardiac output can increase to the same extent.

Anaerobic CO2 production: Under conditions of tissue hypoxia, there is an increased generation of H+ ions from an excessive generation of lactic acid due to an acceleration of anaerobic glycolysis, and the hydrolysis of high-energy phosphates[32]. These H+ ions will then be buffered by the bicarbonate existing in the cells so that CO2 will be produced. Decarboxylation of metabolic intermediates such as α-ketoglutarate and oxaloacetate during hypoxia is, also, a possible but trivial cause of anaerobic CO2 generation[32].

Anaerobic CO2 generation in hypoxic tissues is not simple to identify. Indeed, the effluent venous blood flow can be sufficiently high to wash out the CO2 generated under these conditions of a significant decline in aerobic CO2 production[33]. Consequently, PCO2 could be not increased in the efferent vein, and anaerobic CO2 generation not recognized from the calculation of P (v-a) CO2. Nevertheless, if afferent and efferent blood flows are artificially arrested, hypoxia will happen inside the organ and the sustained CO2 production would then be disclosed by measuring an augmented PCO2 in the sluggish efferent blood flow, in spite of the drop in CO2 generation from the aerobic pathway[34,35].

Influence of cardiac output on P (v-a) CO2

According to the modified Fick equation, P (v-a) CO2 is related to VCO2 and inversely linked to cardiac output. Under steady states of both VO2 and VCO2, P (v-a) CO2 was observed to increase in parallel with the reduction in cardiac output[33,36,37]. In other words, when cardiac output is adapted to VO2, P (v-a) CO2 should not increase due to increased clearance of CO2, whereas P (v-a) CO2 should be high following cardiac output reduction because of a low flow-induced tissue CO2 stagnation phenomenon. Due to the decreasing of transit time a higher than usual addition of CO2 per unit of blood passing the efferent microvessels leads to produce hypercapnia in the venous blood. As long as alveolar respiration is sufficient, a gradient will occur between PvCO2 and PaCO2. However, under spontaneous breathing situations, hyperventilation, stimulated by the decreased blood flow, may reduce PaCO2 and thus may prevent the CO2 stagnation-induced rise in PvCO2[38]. This finding underscores the utility of calculating P (v-a) CO2 rather than simply assessing PvCO2, particularly in the case of spontaneous breathing[39].

Can P (v-a) CO2 be used as a marker of tissue hypoxia?

Marked increases in P (v-a) CO2 were reported in patients during cardiopulmonary resuscitation[40]. Furthermore, higher P (v-a) CO2 values were observed in patients with circulatory failure compared with those without circulatory failure[41]. These observations were attributed to the decrease of blood flow and the development of anaerobic metabolism with anaerobic CO2 production. Thus, it has been suggested that P (v-a) CO2can be used to detect the presence of tissue hypoxia in patients with acute circulatory failure[33,36]. In fact, under conditions of tissue hypoxia with a decreased VO2, the relationship between changes in cardiac output and P (v-a) CO2 are much more complex. Indeed, in these circumstances, the increase in CO2 production related to the anaerobic pathway is counterbalanced by a reduced aerobic CO2 production, so that VCO2 and hence P (v-a) CO2 could be at best unchanged or decreased[37]. Nevertheless, since the k factor should rise during tissue hypoxia[33] while VCO2 must decrease, the resultant effect on P (v-a) CO2 depends mainly on the flow state (cardiac output)[27].

Tissue hypoxia with low blood flow

Experimental studies in which blood flow was progressively reduced, an elevation in P (v-a) CO2 following the reduction in DO2 was reported, while a constant VO2 was measured[33,36,37,42]. In this state of O2 supply-independency and steady CO2 generation, rising of P (v-a) CO2 after flow decrease can be explained clearly by CO2 stagnation.

In those studies, when DO2 was more diminished under its critical value, a drop in VO2 was noticed, insinuating O2 supply-dependency and occurrence of anaerobic metabolism. The progressive widening of P (v-a) CO2 seen before DO2 had achieved the critical point, was amplified by an acute rise in PvCO2 when DO2 declined below that point. The authors[33,36,42] assumed that this brisk increase in P (v-a) CO2 can be utilized as a good indicator of tissue dysoxia. However, since both VCO2 (aerobic production) and venous efferent blood flow decrease, P (v-a) CO2 should not be considerably changed unless very low values of blood flow were achieved during the supply dependent period. Therefore, from the analysis of the data of these experimental studies[33,36,37,42], it can be reasonably supposed that an abrupt increase in P (v-a) CO2 should not be easily attributed to the outset of hypoxia but rather to an additional decrease in cardiac output. This fact can be explained by the two following reasons.

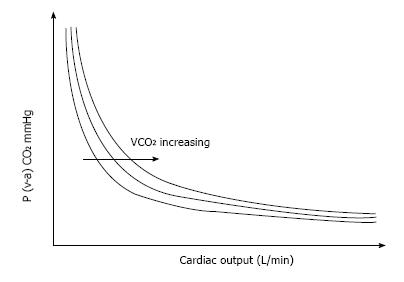

Since the association between P (v-a) CO2 and cardiac output is curvilinear (Fick equation), an enormous rise in P (v-a) CO2 must be noticed for a reduction in cardiac output in its lowest scale. In fact, even if this mathematical phenomenon may be robust under conditions of maintained VCO2, it should be moderated in hypoxic states because the decline in VCO2 leftward shift the isopleth which describes the P (v-a) CO2/cardiac output relationship (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Relationship between the mixed venous-to-arterial PCO2 difference P (v-a) CO2 and cardiac output.

For a constant total CO2 production (VCO2), changes in cardiac output result in large changes in P (v-a) CO2 in the low values of cardiac output, whereas changes in cardiac output will not result in significant changes in P (v-a) CO2 in the high values of cardiac output.

The curvilinearity of the relationship between CvCO2 and PvCO2 may be another cause for this sharp increase in P (v-a) CO2. Indeed, due to this particular relationship, PvCO2 changes are greater than CvCO2 changes at the highest range of CCO2[29]. Furthermore, the disproportions between CCO2 and PCO2 at high values of CCO2 are magnified in the presence of an elevated O2 saturation and by the decrease in venous pH[29], which is frequently associated with the increase in PvCO2 and may be of greater significance if metabolic acidosis coexists (Figure 2). Therefore, in the case of low flow states, P[v-a]CO2 can substantially increase resulting from CO2 stagnation in spite of the decrease in VCO2 as reported in those experimental studies[33,36,37,42].

Tissue hypoxia with maintained or high blood flow

Under conditions of tissue hypoxia with maintained flow state, venous blood flow should be sufficiently elevated to assure adequate clearance of the CO2 generated by the hypoxic cells, so that P (v-a) CO2 should not increase even if the CO2 production is not decreased. Conversely, low flow states can result in a widening of P (v-a) CO2 due to the tissue CO2 stagnation phenomenon[43] even if no additional CO2 production occurs. This point was nicely demonstrated by Vallet et al[44] in a canine model of isolated limb in which a diminished DO2 by reducing blood flow (ischemic hypoxia) was related to a rise in P (v-a) CO2. On the other hand, when blood flow was preserved, but arterial PO2 was decreased by lowering the input oxygen concentration (hypoxic hypoxia), P (v-a) CO2 did not rise despite a significant decline in VO2. This because the preserved blood flow was sufficient to clear the generated CO2[40]. Accordingly, Nevière et al[45] demonstrated that for the same level of induced oxygen supply dependency, P (v-a) CO2 was risen only in ischemic hypoxia but not in hypoxic hypoxia, indicating that augmented P (v-a) CO2 was mostly linked to the reduction in cardiac output. These studies clearly show that the absence of elevated P (v-a) CO2 does not preclude the presence of tissue hypoxia and hence underline the good value of P (v-a) CO2 to detect inadequate tissue perfusion related to its metabolic production but also its poor sensitivity to detect tissue hypoxia. A mathematical model analysis also established that cardiac output plays the key role in the widening of P (v-a) CO2[46].

Clinical studies

Results from clinical investigations in septic shock patients have also supported that the decreased cardiac output is the major determinant in the elevation of P (v-a) CO2[37,38]. Mecher et al[47] observed that septic shock patients with P (v-a) CO2 > 6 mmHg had a significantly lower mean cardiac output when compared to patients with P (v-a) CO2≤ 6 mmHg. No differences in blood lactate levels were found between the two subgroups. Interestingly, the volume expansion engendered a reduction in P (v-a) CO2 associated with an increase in cardiac output only in patients with elevated P (v-a) CO2. Moreover, the changes in cardiac output induced by volume expansion were correlated with changes in P (v-a) CO2 (R = 0.46, P < 0.01). The authors rightly concluded that in patients with septic shock, an elevated P (v-a) CO2 is related to a decreased systemic blood flow. In septic shock patients, Bakker et al[48] similarly found a significant negative correlation between cardiac output and P (v-a) CO2. Thus, a strong association between cardiac output and P (v-a) CO2 is also well documented in septic shock. Furthermore, increased P (v-a) CO2 was found merely in patients with lower cardiac output. In that study, the dissimilarities in P (v-a) CO2 cannot be explained by the inequalities in CO2 production, as implied by the identical VO2 and lactate concentration found in the two groups of patients[48]. On the other hand, many patients in those studies[47,48] had normal P (v-a) CO2 despite the presence of tissue hypoxia, presumably since their elevated cardiac output had simply washed out the CO2 generated in the peripheral circulation.

Creteur et al[49] examined the association between impairment in microcirculatory perfusion and tissue PCO2. They showed that the reperfusion of damaged microcirculation (assessed using orthogonal polarized spectroscopy) was associated with normalized sublingual tissue PCO2 levels. Thus, there is a clear relation between tissue CO2 accumulation and blood flow leading to increasing venous-arterial CO2 gradients.

In short, altogether, these results strengthen the conception that low flow situations act a crucial part in the enlargement of P (v-a) CO2 in states of tissue hypoxia. Elevated P (v-a) CO2 might imply that: (1) cardiac output is not enough under states of supposed tissue hypoxia; and (2) microcirculatory flow is not sufficiently high or adequately distributed to remove the additional CO2 in spite of the existence of normal/high cardiac output.

The P (v-a) CO2 should, therefore, be regarded as an indicator of the ability of an adequate venous blood flow return to clear the CO2 excess rather than as a marker of tissue hypoxia.

Recently, Ospina-Tascon et al[50] have shown that the persistence of high P (v-a) CO2 (≥ 6 mmHg) during the first six hours of reanimation of septic shock patients was linked to more severe multiple organ failure and higher mortality rate (Relative Risk = 2.23, P = 0.01). However, further studies are required to test if P (v-a) CO2 used as a resuscitation endpoint would be associated with improved outcomes.

Central venous-to-arterial PCO2 difference as a target in resuscitation of septic shock

The measurement of P (v-a) CO2 requires the presence of a pulmonary artery catheter, which is rarely practiced nowadays[51]. Since the central venous catheter is implanted in most septic shock patients, the usage of central venous-arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure difference (ΔPCO2) is greatly easier and similarly helpful. Interestingly, a strong agreement between P (v-a) CO2 and ΔPCO2, calculated as the difference between central venous PCO2 sampled from a central vein catheter and arterial PCO2, was reported in critically ill patients[52] and severe sepsis and septic shock patients[53].

As emphasized above, high values of ScvO2 do not preclude the presence of tissue hypoperfusion and hypoxia in cases of impaired O2ER capabilities that can occur in septic shock[21,22]. Since the solubility of CO2 is very high (around 20 times than O2), its capability of spreading out of ischemic tissues into the efferent veins is phenomenal, making it an extremely sensitive indicator of hypoperfusion. Consequently, in conditions where there are O2 diffusion difficulties (resulting from shunted and obstructed capillaries), ‘‘covering’’ reduced O2ER and increased tissue O2 debt, CO2 still diffuses to the efferent veins, ‘‘uncovering’’ the hypoperfusion situation for the clinician when ΔPCO2 is evaluated[54]. Accordingly, Vallée et al[55] tested the hypothesis that the ΔPCO2 can be used as a global indicator of tissue hypoperfusion in reanimated septic shock patients in whom ScvO2 was already greater than 70%. They showed that despite a normalized DO2/VO2 ratio, patients who had impaired tissue perfusion with blood lactate concentration > 2 mmol/L remained with an elevated ΔPCO2 (> 6 mmHg). Also, patients with low ΔPCO2 values had greater lactate decrease and cardiac index values and exhibited a significantly higher reduction in SOFA score than patients with high ΔPCO2. In a prospective study that included 80 patients, we recently examined the usefulness of measuring ΔPCO2 during the initial resuscitation period of septic shock[56]. We found that during the very early period of septic shock, patients who reached a normal ΔPCO2 (≤ 6 mmHg) after six hours of resuscitation had greater decreases in blood lactate and in SOFA score than those who failed to normalize ΔPCO2 (> 6 mmHg). Interestingly, patients who achieved the goals of both ΔPCO2≤ 6 mmHg and ScvO2 > 70% after the first six hours of resuscitation had the greatest blood lactate decrease, which was found to be an independent prognostic factor of ICU mortality[56]. In addition, Du et al[57], in a retrospective study, showed that the normalization of both ScvO2 and ΔPCO2 seems to be a better prognostic factor of outcome after reanimation from septic shock than ScvO2 only. Patients who achieved both targets seemed to clear blood lactate more efficiently[57].

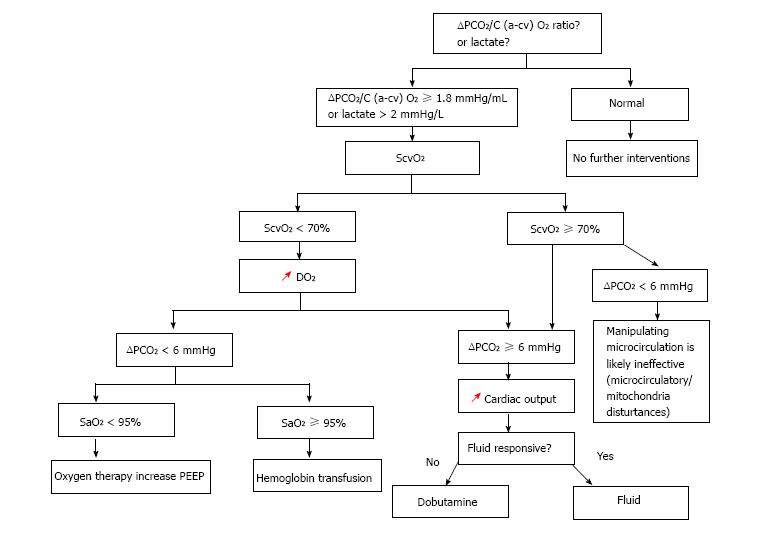

Taken all these studies together[55-57], we believe that monitoring the ΔPCO2 from the beginning of the reanimation of patients with septic shock may be a valuable means to evaluate the adequacy of cardiac output in tissue perfusion and, thus, guiding the therapy (Figure 4). Indeed, in patients with decreased ScvO2, an augmented ΔPCO2 is suggestive of the involvement of low cardiac output, and assessing ΔPCO2 could assist in expediting treatments intended at increasing cardiac output, rather than the arterial O2 saturation and hemoglobin concentration. When ScvO2 is normal/high (≥ 70%), the presence of elevated ΔPCO2 is indicative of the persisting impaired perfusion. ΔPCO2 provides further assistance in making the relevant choices about inotropes and fluids. Randomized clinical trial, however, is required to validate this hypothesis.

Figure 4 ScvO2-∆PCO2 guided protocol.

ScvO2: Central venous oxygen saturation; ∆PCO2: Central venous-to-arterial carbon dioxide tension difference; SaO2: Arterial oxygen saturation; C (a-cv) O2: Central arteriovenous oxygen content difference; DO2: Oxygen delivery; PEEP: Positive end expiratory pressure; red arrows: Increasing.

How to interpret ∆PCO2 in septic shock sates?

As developed extensively above, the ΔPCO2 should be considered as a marker of tissue perfusion (i.e., the adequacy of blood flow to wash out the CO2 generated by the tissues) rather than a marker of tissue hypoxia.

The clinical inferences of this approach can be outlined as follows: (1) in a patient with an initially increased ΔPCO2 (≥ 6 mmHg), clinicians should be aware that blood flow might not be sufficient despite apparent normal macrocirculatory parameters, including ScvO2. Thus, with respect to the metabolic states, an elevated ΔPCO2 could encourage clinicians to rise cardiac output in order to improve tissue perfusion, especially under suspected hypoxic conditions (elevated blood lactate levels). Nevertheless, we should stress out that, in the absence of suspected conditions of tissue ischemia, increasing cardiac output to supranormal values not only failed to demonstrate any benefit but could also be potentially harmful in septic shock patients[58,59]; and (2) A normal ΔPCO2 (< 6 mmHg) would suggest that blood flow is sufficiently high to remove the global CO2 production from the peripheral circulation, and increasing cardiac output could not be a first concern in the management approach even in the presence of tissue hypoxia. On the other hand, clinicians should keep in mind that a normal ΔPCO2 with high cardiac output did not preclude the inadequacy of regional blood flow.

The change in ΔPCO2 - as an index of VCO2/cardiac output ratio - should be interpreted in line with changes in cardiac output and VCO2. Under aerobic conditions, ΔPCO2 along with ScvO2 and O2ER can serve to guide therapy with dobutamine better than cardiac output in septic shock patients[60]. Indeed, dobutamine in parallel to its effects on systemic hemodynamics may increase VO2, and therefore VCO2, through its potential thermogenic effects related to its β1-adrenergic properties[61]. Recently, we showed that during the stepwise increase of dobutamine dose from 0-10 μg/kg per minute, ΔPCO2 decreased in parallel with an increase in cardiac output. However, an unchanged ΔPCO2 was observed when dobutamine was increased from 10-15 μg/kg per minute in spite of the further increase in cardiac output because of the thermogenic effects of the drug at that rate[60]. Thus, ΔPCO2 can assist the clinician in distinguishing between the hemodynamic and the metabolic effects of dobutamine. Similar results were reported in stable chronic heart failure patients, but with P (v-a) CO2[43].

Otherwise, the increase in systemic blood flow can affect VCO2 production under situations of tissue hypoxia. Indeed, under conditions of O2 supply dependency, an increase in cardiac output may lead to an increase in aerobic VCO2 production through the supply-dependent increase in VO2. In this situation, the changes in cardiac output may have no effect on the time-course of ΔPCO2. Accordingly, almost unaffected ΔPCO2 with treatment would not indicate that the treatment has been unsuccessful. In such situation, the therapeutic approach would be preferably kept until achieving a significant drop in ΔPCO2 that would imply that the critical value of DO2 has been overcome.

Moreover, the clinicians should be aware that because the relationship between ΔPCO2 and cardiac output is curvilinear, large variations in cardiac output will not necessary engender important variations in ∆PCO2 (Figure 3). In other words, the interpretation should be cautious in case of high flow states.

Limitations of ∆PCO2

There are many pre-analytical sources of errors in PCO2 measurement that should be avoided to interpret ΔPCO2 correctly: inappropriate sample container, insufficient sample volume compared to anticoagulant volume, and contaminated sample with resident fluid in the line or with air or venous blood, etc. Even after have taken all precautions to minimize the pre-analytical and analytical errors, we, recently, found, in a prospective study[62], that the measurement error for ΔPCO2 was ± 1.4 mmHg and the smallest detectable difference, which is the least change that requires to be measured by a laboratory analyzer to identify a genuine change of measurement, was ± 2 mmHg. This means that the changes in ∆PCO2 should be more than ± 2 mmHg to be considered as real changes and not due to natural variation[62].

Combined analysis of P (v-a) CO2 or ∆PCO2 and O2-derived parameters

Under situations of tissue hypoxia, a drop in VO2 is associated with a decline in aerobic CO2 generation while an anaerobic CO2 generation can still arise[36,37]. Therefore, the VCO2 being reduced less than the VO2, a rise of the respiratory quotient (VCO2/VO2 ratio) can be observed[37,63]. Therefore, the rise in the respiratory quotient was suggested to identify global tissue hypoxia[63]. Because VO2 is equal to the product of cardiac output by the difference between arterial and mixed venous O2 content C (a-mv) O2, and VCO2 is proportional to the product of cardiac output and P (v-a) CO2 the P (v-a) CO2/C (a-mv) O2 ratio could be utilized as indicator of the presence of global tissue hypoxia in critically ill patients. Accordingly, Mekontso-Dessap et al[64] tested this hypothesis in a retrospective study of critically ill patients with normalized cardiac output values and DO2. The authors found a good correlation between P (v-a) CO2/C (a-mv) O2 ratio, presented as a substitute of the respiratory quotient, and arterial blood lactate level, while no correlation was found between blood lactate and P (v-a) CO2 alone and between blood lactate and C (a-mv) O2 alone. Moreover, for a threshold value > 1.4 the P (v-a) CO2/C (a-mv) O2 ratio was able to predict with reliability the presence of hyperlactatemia[64]. The authors concluded that this ratio could be utilized as a reliable indicator of the presence of global anaerobic metabolism in critically ill patients. In a more recent study, Monnet et al[65] found that this ratio, calculated from central venous blood [ΔPCO2/C (a-cv) O2], predicted an increase in VO2 after a fluid-induced increase in DO2 (VO2/DO2 dependency), and thus, can be able to detect the presence of global tissue hypoxia as accurately as the blood lactate level and far better than ScvO2. In a series of 60 fluid-responder patients, we recently found that ΔPCO2/C (a-cv) O2 ratio at baseline predicted accurately the presence of VO2/DO2 dependency phenomenon and better than blood lactate (unpublished data).

In a population of 35 septic shock patients with normalized mean arterial pressure and ScvO2, Mesquida et al[66] showed that the presence of elevated ΔPCO2/C (a-cv) O2 values at baseline was associated with the absence of lactate clearance within the following hours, and this condition was also associated with mortality. However, this was a retrospective study and it was not powered to explore the prognostic value of the ΔPCO2/C (a-cv) O2 ratio. In a recent prospective study that included 135 septic shock patients[67], Ospina-Tascon et al[50] found that the mixed venous-to-arterial CCO2 difference/C (a-mv) O2 ratio at baseline and six hours after resuscitation was an independent prognostic factor of 28 d mortality, but not P (v-a) CO2/C (a-mv) O2 ratio. The authors attributed this discrepancy to the fact that the PCO2/CCO2 relationship is curvilinear rather than linear and is influenced by many factors such as pH and oxygen saturation (Haldane effect), and under these conditions, the mixed venous-to-arterial CCO2 difference/C (a-mv) O2 ratio might not be equivalent to P (v-a) CO2/C (a-mv) O2 ratio.

From the results of those above studies[64-67], we believe that we can reasonably admit that the ΔPCO2/C (a-cv) O2 ratio can be used as an indicator of the presence of global tissue hypoxia in critically ill patients. Further clinical trials are needed to assess its prognostic value in patients with septic shock.