Published online Sep 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i3.106387

Revised: April 3, 2025

Accepted: May 7, 2025

Published online: September 9, 2025

Processing time: 144 Days and 7.5 Hours

Sepsis and septic shock pose critical public health challenges with high mortality, particularly in critical care. While racial differences in sepsis incidence are documented, the impact of race on sepsis outcomes remains inconsistent.

To evaluate racial disparities in clinical outcomes among patients hospitalized with septic shock, focusing on in-hospital mortality, length of stay (LOS), and hospitalization costs.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the National Inpatient Sample database from 2016 to 2021. Patients diagnosed with septic shock were identified using ICD-10 code R65.21. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality; secondary outcomes included trends in septic shock hospitalizations, mortality, length of stay, and cost of hospitalizations.

Among 3581504 hospitalizations for septic shock, the racial distribution was 67% Non-Hispanic White (NHW), 15% Non-Hispanic Black (NHB), 11% Hispanic, and 7% other groups, with a mean age of 66.3 years. In-hospital mor

We found higher mortality among NHB, Hispanic, and other racial groups in septic shock patients, likely driven by higher risk of in-hospital complications among these racial groups. This highlights the need for future research to identify the factors contributing to the adverse outcomes in these populations.

Core Tip: Non-Hispanic Black (NHB) and Hispanic patients faced higher adjusted in-hospital mortality compared to Non-Hispanic White patients, primarily driven by higher incidence of in-hospital complications. Mortality increased sharply during 2020–2021, particularly among Hispanic patients. NHB patients had the longest hospital stays, while "Other" racial groups incurred the highest costs. Structural inequities in healthcare access and pandemic-related stressors likely contributed to worsening outcomes in marginalized groups, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions.

- Citation: Ang SP, Chia JE, Iglesias J. Racial differences in outcomes among patients with septic shock: A national cohort study. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(3): 106387

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i3/106387.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i3.106387

Sepsis, a life-threatening condition characterized by a dysregulated host response to infection, remains a significant global health concern, affecting millions of individuals annually and contributing substantially to morbidity and mortality in healthcare settings worldwide[1]. Septic shock, the most severe form of sepsis, is associated with particularly high mortality rates, ranging from 40% to 60% in various studies[2-4]. The complex pathophysiology of sepsis, involving intricate interactions between the host immune system and pathogenic microorganisms, poses considerable challenges in diagnosis and management. Despite advances in critical care medicine and the implementation of standardized treatment protocols, such as the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, outcomes for patients with septic shock remain suboptimal[5,6]. In recent years, there has been growing recognition of the impact of social determinants of health on sepsis out

The existence of racial disparities in healthcare outcomes is well-documented across various medical conditions, and sepsis is no exception[10]. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated higher incidence rates of sepsis among racial and ethnic minority populations, particularly African Americans and Hispanics, compared to their White counterparts. These disparities have been attributed to a complex interplay of factors, including differences in socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, prevalence of comorbidities, and genetic predisposition to infection. However, the literature on racial disparities in sepsis outcomes, particularly in the context of septic shock, has yielded conflicting results. Some studies have reported higher mortality rates among minority patients, while others have found no significant differences or even lower mortality rates in certain minority groups after adjusting for confounding factors. These inconsistencies highlight the need for comprehensive, large-scale studies that can provide a more definitive understanding of the relationship between race and septic shock outcomes. Furthermore, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought renewed attention to health disparities, with emerging evidence suggesting that racial and ethnic minorities have been disproportionately affected by severe COVID-19 and its complications, including sepsis[11-13]. This highlights the urgency of investigating racial disparities in septic shock outcomes in the context of evolving healthcare challenges.

The present study aims to address this gap in knowledge by conducting a comprehensive analysis of racial disparities in septic shock outcomes using a large, nationally representative database.

This retrospective cohort study utilized data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database spanning 2016 to 2021. The NIS, a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) and sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, represents the largest publicly accessible all-payer inpatient healthcare database in the United States[14]. It includes data from approximately 7 million hospitalizations annually, which represents a 20% stratified sample of discharges from United States community hospitals, excluding rehabilitation and long-term acute care facilities. Given the use of this deidentified, limited dataset, ethical approval is not required according to HCUP data use agre

Adult patients (≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of septic shock were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code R65.21. This ICD-10 code has been validated in prior studies as a reliable identifier of septic shock cases in administrative datasets[15,16]. Patients with missing data on key variables (age, sex, race, or mortality) were excluded from the analysis.

Demographic variables included age, sex, and race/ethnicity, categorized as White, Black, Hispanic, and Other (which included Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, and other races or ethnicities). We also collected data on hospital characteristics (teaching status, bed size, urban/rural location), type of admission (elective vs non-elective), primary payer (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, no charge, other), and relevant comorbidities based on ICD-10-CM codes.

The primary outcome of interest was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI), AKI requiring dialysis, use of mechanical ventilation, trends in septic shock hospitalizations and mortality, length of stay (LOS), and cost of hospitalization.

To account for the complex sampling design of the NIS, we utilized survey-based analysis with appropriate weighting to generate national estimates. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value of < 0.05. Given that missing data were minimal, we performed a complete case analysis. Unadjusted and adjusted analyses were conducted to examine racial/ethnic differences in in-hospital outcomes. For the unadjusted analysis, continuous variables were summarized as weighted means with SD while categorical variables were expressed as weighted frequencies with percentages. Comparisons across racial/ethnic groups were conducted using weighted χ2 tests for categorical variables and weighted linear regression analysis for continuous variables. For trend analysis over the study period, the Cochran-Armitage test was applied to examine trends in septic shock hospitalizations and mortality rates.

In the adjusted analysis, multivariable logistic regression models were used to compare outcomes between NHB vs NHW and Hispanic vs NHW groups. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each outcome, controlling for potential confounders including age, gender, hospital characteristics and comorbidities significant on univariate analysis.

We further constructed a multivariable logistic regression model to assess race/ethnicity as a predictor of in-hospital mortality. Model 1 was adjusted for potential confounders, including age, sex, comorbidities, hospital characteristics, admission type, and primary payer, as well as any covariates found significant in univariate analyses. Model 2 further adjusted for in-hospital events including AKI, AKI requiring dialysis and use of mechanical ventilation. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v18 (College Station, TX, United States).

In this contemporary 6-year period, we analyzed 3581504 septic shock hospitalizations. The demographic breakdown of the patients included 67% (n = 2391504) White, 15% Black (n = 524535), 11% (n = 405145) Hispanic, and 7% (n = 260320) from other racial groups. Mean age of the cohort was 66.3 (15.3) years. Specifically, the mean age of patients was 67.69 ± 14.75 years for NHWs, 63.38 ± 15.39 years for NHBs, 62.58 ± 16.74 years for Hispanics, and 65.64 ± 16.37 years for others, with significant age differences across groups (P < 0.001). The proportion of female patients was 47.3% overall, with similar gender distributions across racial groups. Details of baseline characteristics are available in Table 1.

| Variables | NHW (n = 2391504) | NHB (n = 524535) | Hispanics (n = 405145) | Others (n = 260320) | P value |

| Age | 67.69 ± 14.75 | 63.38 ± 15.39 | 62.58 ± 16.74 | 65.64 ± 16.37 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 1130920 (47.3) | 256595 (48.9) | 182825 (45.1) | 118395 (45.5) | |

| Hospital bed size | 0.0035 | ||||

| Small | 450774 (18.8) | 93780 (17.9) | 71750 (17.7) | 45055 (17.3) | |

| Medium | 689954 (28.9) | 151535 (28.9) | 124735 (30.8) | 75240 (28.9) | |

| Large | 1250775 (52.3) | 279220 (53.2) | 208660 (51.5) | 140025 (53.8) | |

| Hospital teaching status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Rural | 197030 (8.2) | 22795 (4.3) | 6850 (1.7) | 8350 (3.2) | |

| Urban non-teaching | 506685 (21.2) | 77955 (14.9) | 89720 (22.1) | 51625 (19.8) | |

| Urban teaching | 1687789 (70.6) | 423785 (80.8) | 308575 (76.2) | 200345 (77.0) | |

| Admission | < 0.001 | ||||

| Elective | 102625 (4.3) | 16710 (3.2) | 14610 (3.6) | 9960 (3.8) | |

| Missing | 3385 (0.1) | 765 (0.1) | 460 (0.1) | 330 (0.1) | |

| Primary payment coverage | < 0.001 | ||||

| Medicare | 1609239 (67.3) | 317860 (60.6) | 206445 (51.0) | 144475 (55.5) | |

| Medicaid | 252545 (10.6) | 100525 (19.2) | 97345 (24.0) | 51335 (19.7) | |

| Private insurance | 403975 (16.9) | 76220 (14.5) | 65855 (16.3) | 47415 (18.2) | |

| Self-pay | 55375 (2.3) | 14470 (2.8) | 23785 (5.9) | 9115 (3.5) | |

| No charge | 4000 (0.2) | 1100 (0.2) | 1590 (0.4) | 550 (0.2) | |

| Other | 63630 (2.7) | 13530 (2.6) | 9660 (2.4) | 7080 (2.7) | |

| Missing | 2740 (0.1) | 830 (0.2) | 465 (0.1) | 350 (0.1) | |

| Median household income, $ | < 0.001 | ||||

| 1-28999 | 647215 (27.1) | 266905 (50.9) | 158690 (39.2) | 63695 (24.5) | |

| 29000-35999 | 651700 (27.3) | 110845 (21.1) | 100835 (24.9) | 53255 (20.5) | |

| 36000-46999 | 575325 (24.1) | 82855 (15.8) | 86380 (21.3) | 61235 (23.5) | |

| 47000+ | 475645 (19.9) | 54170 (10.3) | 50045 (12.4) | 74660 (28.7) | |

| Missing | 41620 (1.7) | 9760 (1.9) | 9195 (2.3) | 7475 (2.9) | |

| Hospital region | < 0.001 | ||||

| Northeast | 431420 (18.0) | 82520 (15.7) | 51890 (12.8) | 51375 (19.7) | |

| Midwest | 551250 (23.1) | 100175 (19.1) | 24830 (6.1) | 25200 (9.7) | |

| South | 958410 (40.1) | 288280 (55.0) | 158370 (39.1) | 66325 (25.5) | |

| West | 450424 (18.8) | 53560 (10.2) | 170055 (42.0) | 117420 (45.1) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Congestive heart failure | 879550 (36.8) | 205260 (39.1) | 120295 (29.7) | 84100 (32.3) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1036490 (43.3) | 193560 (36.9) | 133205 (32.9) | 96575 (37.1) | < 0.001 |

| Valvular heart diseases | 225415 (9.4) | 37995 (7.2) | 25705 (6.3) | 19340 (7.4) | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary circulatory disorders | 233610 (9.8) | 62480 (11.9) | 33895 (8.4) | 23065 (8.9) | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 264480 (11.1) | 54685 (10.4) | 33775 (8.3) | 23630 (9.1) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1497265 (62.6) | 365370 (69.7) | 247160 (61.0) | 159030 (61.1) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 732830 (30.6) | 124415 (23.7) | 73185 (18.1) | 53225 (20.4) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 804655 (33.6) | 221880 (42.3) | 190655 (47.1) | 109730 (42.2) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 683580 (28.6) | 215725 (41.1) | 128585 (31.7) | 81530 (31.3) | < 0.001 |

| Liver disease | 442915 (18.5) | 97530 (18.6) | 94405 (23.3) | 56030 (21.5) | < 0.001 |

| Anemia | 170080 (7.1) | 45145 (8.6) | 30785 (7.6) | 19385 (7.4) | < 0.001 |

| AIDS | 8715 (0.4) | 14495 (2.8) | 4640 (1.1) | 1970 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer | 333525 (13.9) | 73540 (14.0) | 49790 (12.3) | 39595 (15.2) | < 0.001 |

| Rheumatologic disorders | 95845 (4.0) | 20310 (3.9) | 15035 (3.7) | 8565 (3.3) | < 0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 615690 (25.7) | 151545 (28.9) | 126840 (31.3) | 81305 (31.2) | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 410760 (17.2) | 89985 (17.2) | 76005 (18.8) | 31645 (12.2) | < 0.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 1865804 (78.0) | 424535 (80.9) | 322810 (79.7) | 207375 (79.7) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 184730 (7.7) | 33290 (6.3) | 33860 (8.4) | 18570 (7.1) | < 0.001 |

| Drug abuse | 138285 (5.8) | 27410 (5.2) | 21515 (5.3) | 10910 (4.2) | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 326810 (13.7) | 42430 (8.1) | 36215 (8.9) | 19590 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | 328675 (13.7) | 59840 (11.4) | 30585 (7.5) | 20615 (7.9) | < 0.001 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score | 5.51 ± 2.20 | 5.82 ± 2.22 | 5.31 ± 2.21 | 5.33 ± 2.18 | < 0.001 |

Hospital bed size distribution varied significantly across racial groups (P = 0.0035), with most patients across all groups being admitted to large hospitals (52.5% overall). NHWs had the highest proportion of patients in rural hospitals (8.2%), while NHBs, Hispanics, and Others were more frequently treated in urban teaching hospitals, with NHBs having the highest representation (80.8%). Elective admissions were low across all racial groups, representing approximately 4% of the total admissions.

There were significant differences in median household income (P < 0.001), with NHWs having a higher representation in the highest income quartile (≥ $47000), while NHBs and Hispanics were more likely to be from the lowest income quartile (≤ $28999). Medicare was the primary payer for most patients (63.7%), with the highest proportion among NHWs (67.3%), followed by NHBs (60.7%), Hispanics (51.0%), and Others (55.6%). Medicaid coverage was more prevalent among NHBs (19.2%) and Hispanics (24.1%), compared to NHWs (10.6%).

Congestive heart failure was the most common cardiac comorbidity, affecting 35.9% of patients, with higher prevalence in NHWs (36.8%) and NHBs (39.1%) compared to Hispanics (29.7%). Cardiac arrhythmias were present in 40.8% of the total population, with significant variation across racial groups (NHWs: 43.4%, NHBs: 36.9%, Hispanics: 32.9%). Chronic lung disease affected 27.5% of patients, most frequently in NHWs (30.6%), followed by NHBs (23.7%) and Hispanics (18.1%). Pulmonary circulatory disorders were more common in NHBs (11.9%) and others (8.9%). Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was present in 30.9% of patients, with the highest prevalence in NHBs (41.1%), followed by others (31.3%) and NHWs (28.6%). Hypertension was the most prevalent comorbidity, affecting 63.3% of patients, with NHBs having the highest prevalence (69.6%), followed by NHWs (62.6%) and Hispanics (61.0%). Diabetes was observed in 37.0% of patients, most commonly among NHBs (42.3%) and Hispanics (47.1%). Anemia affected 7.4% of the population, with higher rates in NHBs (8.6%) compared to NHWs (7.1%). Coagulopathy was present in 27.2% of patients, most frequently in NHWs (25.8%). Obesity was reported in 17.0% of patients, with the highest prevalence in NHWs (17.2%) and the lowest in others (12.2%). Alcohol and drug abuse were more common among NHWs and NHBs compared to Hispanics and Others.

In-hospital mortality rates were highest among NHB at 36.77%, followed by others (36.62%), Hispanics (35.52%), and NHW at 32.27% (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Mechanical ventilation was more commonly required among NHBs (54.13%), compared to Hispanics (48.85%), others (49.84%), and NHWs (43.39%) (P < 0.001). In terms of AKI, NHW experienced the highest rate of AKI (67.67%) while the Hispanics had the lowest (63.90%) (P < 0.001). However, AKI requiring dialysis was most prevalent among NHBs (12.36%), compared to NHWs (8.36%), Hispanics (10.94%), and others (9.93%) (P < 0.001). The cost of hospitalization and LOS varied significantly by race. Hispanics and the other racial/ethnicity group incurred the highest hospitalization costs, with averages of $58786 ± $89798 and $60093 ± $94254, respectively. NHBs followed with $52587 ± $75439, while NHWs had the lowest costs at $41384 ± $61342. The mean LOS was longest for NHBs (15.04 ± 18.20 days), followed by Hispanics (14.32 ± 18.02 days), and other racial/ethnicity group (13.86 ± 17.58 days), with NHWs having the shortest stays at 11.59 ± 13.73 days.

| Variables | NHW (n = 2391504) | NHB (n = 524535) | Hispanics (n = 405145) | Others (n = 260320) | P value |

| Mortality | 771800 (32.3) | 192865 (36.8) | 143900 (35.5) | 95335 (36.6) | < 0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1037710 (43.4) | 283910 (54.1) | 197920 (48.9) | 129745 (49.8) | < 0.001 |

| AKI | 1618359 (67.7) | 353470 (67.4) | 258870 (63.9) | 168670 (64.8) | < 0.001 |

| AKI requiring dialysis | 199885 (8.4) | 64850 (12.4) | 44320 (10.9) | 25840 (9.9) | < 0.001 |

| Cost of hospitalization | 41384 ± 61342 | 52587 ± 75439 | 58786 ± 89798 | 60093 ± 94254 | < 0.001 |

| LOS | 11.59 ± 13.73 | 15.04 ± 18.20 | 14.32 ± 18.02 | 13.86 ± 17.58 | < 0.001 |

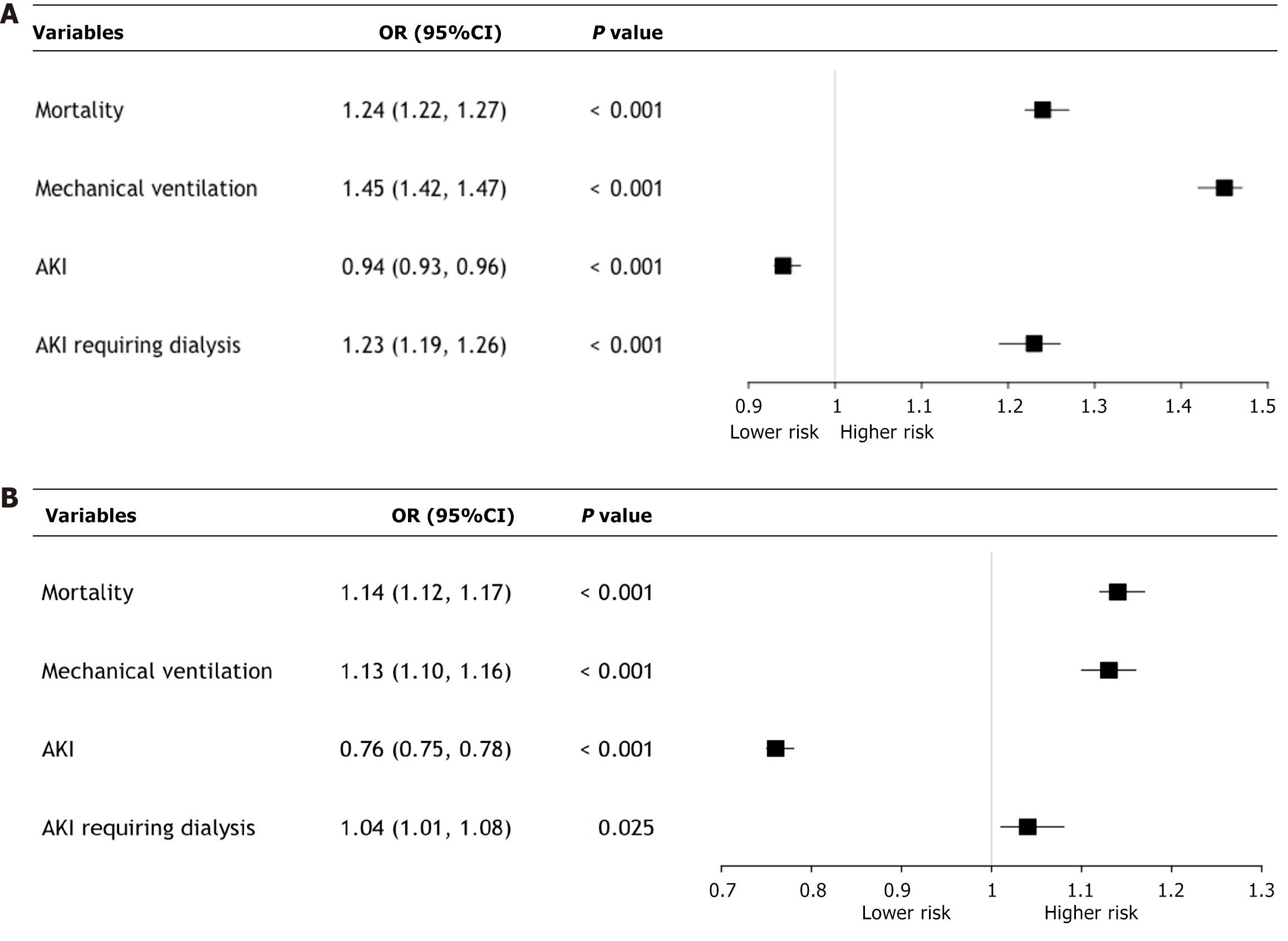

For NHB vs NHW comparisons, NHB patients were associated with significantly higher adjusted odds of in-hospital mortality (aOR: 1.24, 95%CI: 1.22–1.27, P < 0.001) and the need for mechanical ventilation (aOR: 1.45, 95%CI: 1.42–1.47, P < 0.001) (Figure 1A). Conversely, NHB patients were associated with lower odds of AKI (aOR: 0.94, 95%CI: 0.93–0.96, P < 0.001) but demonstrated higher odds of AKI requiring dialysis (aOR: 1.23, 95%CI: 1.19–1.26, P < 0.001).

In the Hispanic vs NHW comparisons, Hispanic patients were associated with elevated odds of mortality (aOR: 1.14, 95%CI: 1.12–1.17, P < 0.001) and mechanical ventilation (aOR: 1.13, 95%CI: 1.10–1.16, P < 0.001) (Figure 1B). However, Hispanics had significantly lower odds of AKI (aOR: 0.76, 95%CI: 0.75–0.78, P < 0.001), while the odds of AKI requiring dialysis were marginally higher (aOR: 1.04, 95%CI: 1.01–1.08, P = 0.025). Results of adjusted analysis are summarized in Table 3.

| Variables | NHB vs NHW1 | Hispanics vs NHW2 | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Mortality | 1.24 (1.22-1.27) | < 0.001 | 1.14 (1.12-1.17) | < 0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.45 (1.42-1.47) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (1.10-1.16) | < 0.001 |

| AKI | 0.94 (0.93-0.96) | < 0.001 | 0.76 (0.75-0.78) | < 0.001 |

| AKI requiring dialysis | 1.23 (1.19-1.26) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (1.01-1.08) | 0.025 |

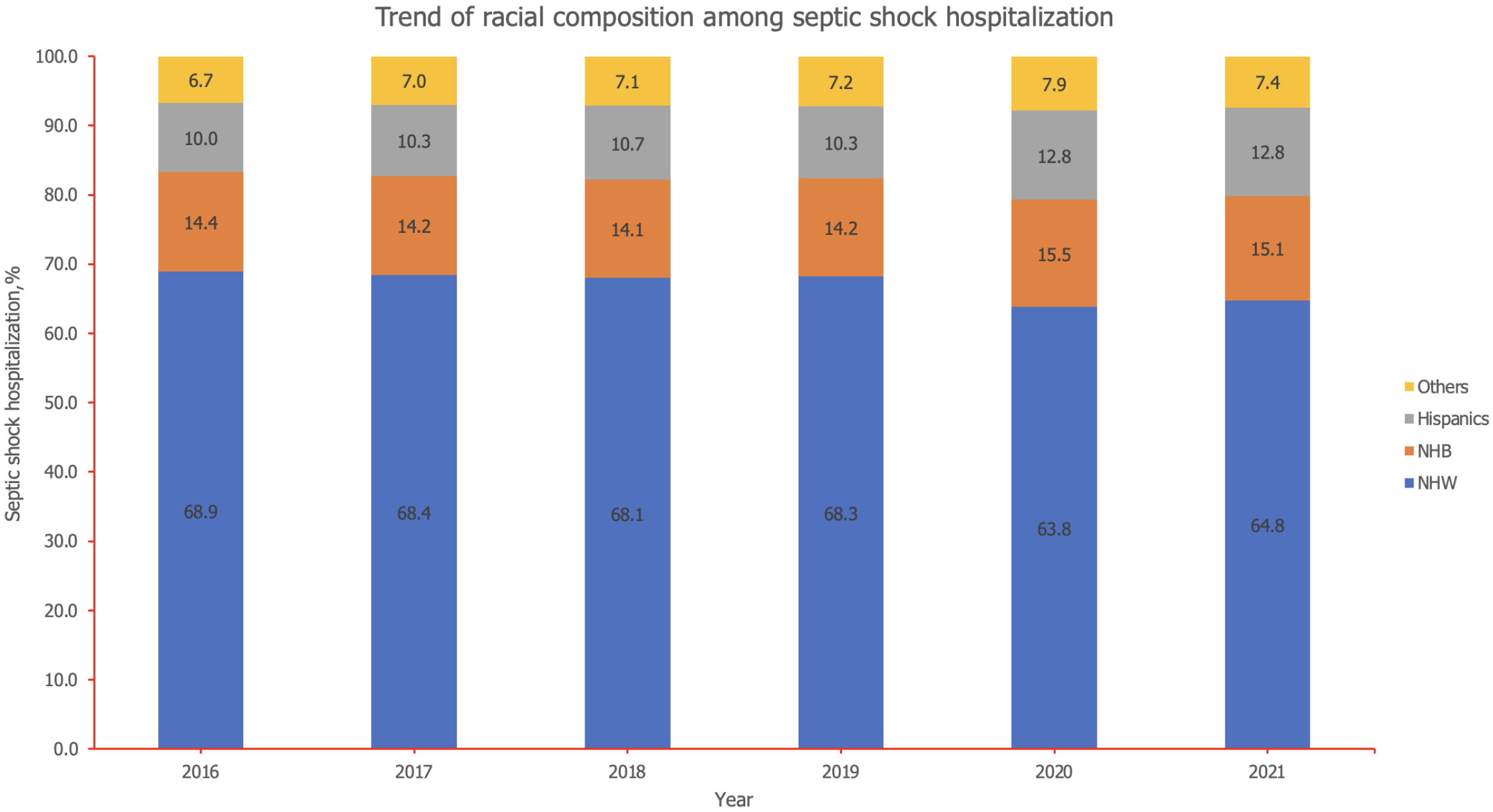

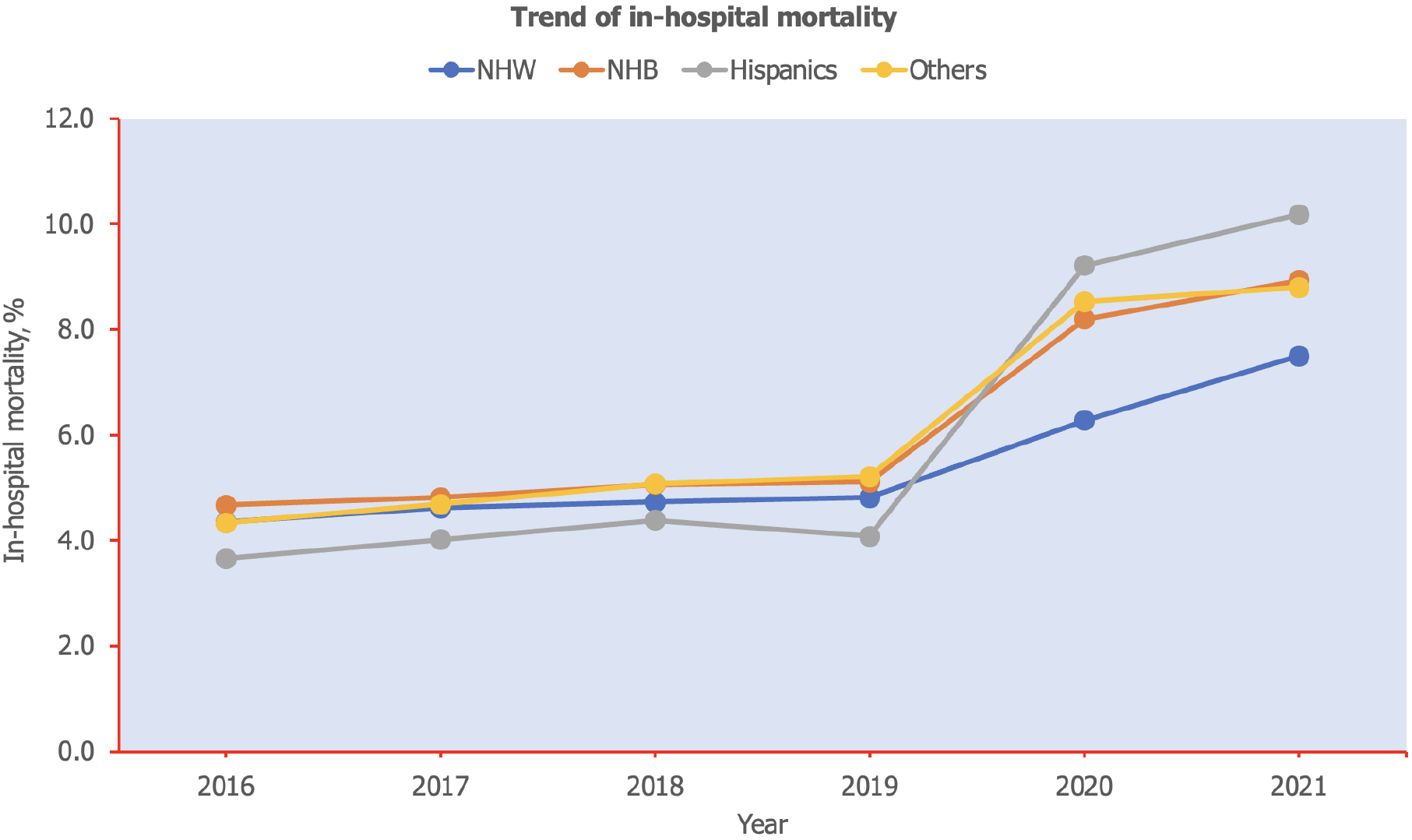

Between 2016 and 2021, the racial composition of septic shock cases shifted notably: The proportion of NHW decreased from 68.9% to 64.8%, indicating a downward trend (Figure 2). In contrast, the percentages for Hispanics and other racial groups increased, with Hispanics rising from 10.0% to 12.8% and others from 6.7% to 7.4%. NHB remained relatively stable around 14%, with a slight uptick to over 15% in the last two years. Overall mortality rate among septic shock hospitalization was 33.6%. The trend of mortality from 2016 to 2021 shows a consistent increase across all racial groups, with the most pronounced rise starting in 2020 (Figure 3). NHW saw mortality rise from 4.3% in 2016 to 7.5% in 2021 (P-trend = 0.01). NHB experienced a similar upward trend, increasing from 4.7% to 8.9% (P-trend = 0.01). Hispanics showed the most dramatic growth in mortality, more than doubling from 3.7% in 2016 to 10.2% in 2021 (P-trend = 0.02). The individuals from other racial groups also saw a significant increase from 4.3% to 8.8% during this period (P-trend = 0.01).

Two models were employed to assess the predictors of in-hospital mortality, with each model adjusting for various patient demographics, hospital characteristics, socioeconomic factors, and comorbidities. Model 1 primarily includes baseline demographic and hospital factors, while Model 2 further incorporates in-hospital events (Table 4). In Model 1, NHB patients (OR: 1.17, 95%CI: 1.15–1.19, P < 0.001), Hispanic patients (OR: 1.12, 95%CI: 1.09–1.14, P < 0.001), and individuals of other races (OR: 1.14, 95%CI: 1.12–1.17, P < 0.001) all have higher odds of in-hospital mortality compared to NHW patients. Similarly, patients in urban teaching hospitals (OR: 1.30, 95%CI: 1.26–1.35, P < 0.001) and those from large hospitals (OR: 1.16, 95%CI: 1.13–1.18, P < 0.001) also showed higher odds of mortality. Socioeconomic factors were inversely associated with mortality risk, with higher median household income associated with lower mortality.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| NHW | Ref | Ref | ||

| NHB | 1.17 (1.15-1.19) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | < 0.001 |

| Hispanics | 1.12 (1.09-1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.08 (1.06-1.11) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 1.14 (1.12-1.17) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.05-1.10) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.017 | 1.10 (1.09-1.12) | < 0.001 |

| Elective | 1.15 (1.12-1.19) | < 0.001 | 1.12 (1.08-1.16) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital bed size | ||||

| Small | Ref | Ref | ||

| Medium | 1.09 (1.07-1.12) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.02-1.08) | < 0.001 |

| Large | 1.16 (1.13-1.18) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.04-1.09) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital teaching status | ||||

| Rural | Ref | Ref | ||

| Urban non-teaching | 1.17 (1.13-1.21) | < 0.001 | 1.02 (0.98-1.06) | 0.307 |

| Urban teaching | 1.30 (1.26-1.35) | < 0.001 | 1.08 (1.04-1.11) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital region | ||||

| Northeast | Ref | Ref | ||

| Midwest | 0.76 (0.74-0.79) | < 0.001 | 0.77 (0.75-0.80) | < 0.001 |

| South | 0.86 (0.83-0.88) | < 0.001 | 0.87 (0.84-0.89) | < 0.001 |

| West | 0.85 (0.82-0.87) | < 0.001 | 0.87 (0.85-0.90) | < 0.001 |

| Median household income | ||||

| 1-28999 | ||||

| 29000-35999 | 0.93 (0.91-0.94) | < 0.001 | 0.94 (0.93-0.96) | < 0.001 |

| 36000-46999 | 0.91 (0.89-0.92) | < 0.001 | 0.94 (0.92-0.95) | < 0.001 |

| 47000+ | 0.86 (0.85-0.88) | < 0.001 | 0.91 (0.89-0.93) | < 0.001 |

| Primary payment | ||||

| Medicare | Ref | Ref | ||

| Medicaid | 0.82 (0.80-0.83) | < 0.001 | 0.73 (0.71-0.74) | < 0.001 |

| Private insurance | 0.91 (0.89-0.92) | < 0.001 | 0.83 (0.82-0.85) | < 0.001 |

| Self-pay | 1.10 (1.06-1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 0.11 |

| No charge | 0.76 (0.66-0.87) | < 0.001 | 0.73 (0.64-0.83) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 1.32 (1.27-1.38) | < 0.001 | 1.35 (1.29-1.41) | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Congestive heart failure | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | 0.001 | 0.97 (0.96-0.98) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1.37 (1.35-1.39) | < 0.001 | 1.28 (1.27-1.30) | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary circulatory disorders | 1.16 (1.14-1.18) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.08-1.13) | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.20 (1.17-1.22) | < 0.001 | 1.27 (1.24-1.29) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 1.04 (1.02-1.05) | < 0.001 | 0.95 (0.94-0.96) | < 0.001 |

| CKD | 1.07 (1.06-1.09) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.09-1.12) | < 0.001 |

| Liver disease | 2.07 (2.04-2.10) | < 0.001 | 1.82 (1.80-1.85) | < 0.001 |

| Rheumatologic disorders | 0.95 (0.92-0.97) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 0.879 |

| Coagulopathy | 1.35 (1.33-1.37) | < 0.001 | 1.22 (1.20-1.23) | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 0.86 (0.85-0.88) | < 0.001 | 0.77 (0.76-0.79) | < 0.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 1.33 (1.31-1.35) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.03-1.07) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.93 (0.91-0.95) | < 0.001 | 0.89 (0.87-0.91) | < 0.001 |

| Drug abuse | 0.70 (0.69-0.72) | < 0.001 | 0.74 (0.72-0.75) | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 0.63 (0.61-0.64) | < 0.001 | 0.57 (0.56-0.59) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.96 (0.95-0.97) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 0.717 |

| Anemia | 0.68 (0.66-0.69) | < 0.001 | 0.71 (0.70-0.73) | < 0.001 |

| Cancer | 1.45 (1.43-1.47) | < 0.001 | 1.73 (1.70-1.76) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 0.94 (0.93-0.95) | < 0.001 | 0.93 (0.91-0.94) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | 0.78 (0.77-0.80) | < 0.001 | 0.77 (0.76-0.79) | < 0.001 |

| AKI | - | - | 1.34 (1.32-1.36) | < 0.001 |

| AKI requiring dialysis | - | - | 1.37 (1.34-1.40) | < 0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | - | - | 3.90 (3.85-3.95) | < 0.001 |

Model 2 builds on this framework by incorporating in-hospital events including AKI, AKI requiring dialysis and use of mechanical ventilation. In Model 2, NHB (OR: 1.04), Hispanic (OR: 1.08), and other racial groups (OR: 1.07) had higher odds of mortality compared to NHW, while female sex was also associated with increased mortality (OR: 1.10). The incidence of in-hospital events including the use of mechanical ventilation (OR: 3.90), AKI (OR: 1.34), and AKI requiring dialysis (OR: 1.37) were the strongest predictors of mortality.

In this contemporary six-year period, analysis of the NIS database involving patients with septic shock, we discovered significant racial disparities between NHB and other minorities when compared to their NHW counterparts, showing a higher cost of care, longer hospital length of stay, and higher mortality. The current study demonstrates that the causes of these racial disparities are multifactorial, such as the burden of comorbidities, geographical, cultural, and socioeconomic. The disparity in the in-hospital mortality is markedly attenuated when adjusting for comorbidities, AKI, AKI requiring dialysis, mechanical ventilation, socioeconomic status, and hospital-level factors.

Hospital-level factors may contribute to disparities in sepsis care. Consistent with other studies, the current study demonstrates that over 80% of NHB received care at large urban teaching hospitals[17]. This finding raises the issue that these generally "non-profit safety net hospitals", which are usually understaffed and underfunded, may account for the disparity in sepsis care and mortality[18,19]. Mayr et al[20] and others have demonstrated that hospitals caring for minority patients have a higher severity of illness, multi-organ failure, and mortality. Recent studies have demonstrated that NHB and other minorities receive care that does not meet the standards of the sepsis bundle. Corl et al[21], evaluating over 50000 emergency room encounters from 2014-2016, demonstrated that although during the first quarter of 2014, there were no differences between completion of the 3-hour sepsis bundle between NHW, NHB and other minorities in completion of the 3-hour sepsis bundle, however, for the remaining time period of the study NHW experienced a greater adjusted performance rate of completion rate for the 3-hour sepsis bundle over NHB and other minority group counterparts. In a prospective observational cohort involving 28 hospitals, Mayr and colleagues demonstrated that NHBs with community-acquired pneumonia were less likely to initiate timely antibiotics[22]. NHB patients appeared to have lower quality and higher intensity of care; however, when adjusted for case mix and variability of care across hospitals, there was no care disparity between NHB and their white counterparts within the same hospital[22]. In comparison to non-safety-net hospitals, sepsis admissions to safety-net hospitals sepsis are associated with a higher mortality. Law et al[17], in a large cohort study, suggested these differences may be attributed to less use of hospice care in safety net hospitals, which then attributes the death to hospitalization rather than hospice.

We found significant differences in median household income, with more NHB and Hispanics being in the lower income brackets. Additionally, Medicaid as a primary source of insurance was more prevalent in NHB and Hispanic patients. Socioeconomic factors are another driving force for healthcare disparities as they impact the social determinants of health. Income inequality may lead to less access to better educational services, limited access to healthier living conditions, and care focusing on health promotion and disease prevention[23]. Reliance on Medicaid services may limit an individual's access to provider networks and specialist care. The financial constraints of persons in the lower income brackets limit their ability to pay out of pocket health expenditures, which may lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment. Interestingly, Vazquez Guillamet et al[24] displayed that race was not an independent risk factor for sepsis outcomes when their analysis was adjusted for socioeconomic status.

Among patients with sepsis, the number of chronic comorbidities increases the risk for organ dysfunction[25]. Our study demonstrated that NHB, Hispanics, and other races have a higher burden of comorbidities. When compared to NHW, underlying liver disease, CKD, hypertension, HIV/AIDs, and diabetes were more prevalent among all minority groups. In the current study, multivariable logistic regression demonstrated that CKD and liver disease were significant predictors of mortality. Similarly, Esper et al[25] analysis of the National Hospital Discharge Survey concluded that chronic comorbidities partially account for the healthcare disparities in sepsis. In fact, presence of cirrhosis has been shown to have adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients[26,27]. Chebl et al[28] studied 7906 ICU patients with sepsis, of which 6.3% had cirrhosis and found that patients with underlying cirrhosis had a higher crude mortality rate compared to patients without cirrhosis (65% vs 32%). On multivariable analysis, they reported that cirrhosis patients were associated with more than twice the odds of in-hospital mortality compared to that without cirrhosis[28].

Organ injuries such as respiratory failure and AKI are common complications among patients hospitalized with sepsis, which may require invasive medical therapy such as mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapy. The requirement of mechanical ventilation and or renal replacement in septic patients is associated with increased mortality[29]. Consistent with current epidemiologic data, in the current study, multivariable logistic regression analysis demonstrates that AKI, AKI requiring dialysis, and the need for mechanical ventilation are significant predictors of mortality and may account in part for racial disparities in mortality. Several studies evaluating hospitalized patients with different case mixes have demonstrated significant racial disparities in the development of AKI, with a higher prevalence of AKI developing among NHB[30]. These disparities seem to become attenuated when adjusted for comorbidities and socioeconomic status[30]. In contrast to other studies, the current study shows that the development of AKI occurred with increasing frequency among NHW[30]. However, there were significant differences in the development of AKI requiring dialysis, particularly among NHB and other minorities compared to their NHW counterparts. Although Hsu et a[31] previously described the trend in AKI requiring dialysis as more prevalent among hospitalized NHBs, to our knowledge, the current study is the first to describe this disparity among patients hospitalized with septic shock. Several studies evaluating racial disparities in the use of mechanical ventilation have yielded conflicting results, with some studies demonstrating a higher frequency of mechanical ventilation utilization among NHB and other minorities while others have not[32]. In the current analysis, the utilization of mechanical ventilation was greater among NHB, Hispanics, and other minorities than non-NHW. Notably, adjusting for AKI, AKI requiring dialysis and mechanical ventilation attenuated the racial disparity in mortality.

Our study's primary strengths lie in the comprehensive analysis of multiple variables that may contribute to healthcare disparities within a sample reflective of the United States healthcare system. By analyzing an extensive range of sociodemographic and clinical factors, we contribute novel insights into healthcare disparities, supporting the development of targeted public health interventions and policies designed to mitigate inequities in healthcare access and outcomes. Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, the NIS is an administrative database, which inherently relies on coding accuracy. Although the ICD-10-CM code used to identify septic shock has been validated, there remains the possibility of variability in coding practice, coding errors or misclassifications that could impact case identification. Additionally, the NIS lacks certain clinical details, such as the severity of illness, laboratory results, treatments, and time-to-treatment, which may influence patient outcomes but are not captured in this dataset. This study’s retrospective observational design limits the ability to establish causal relationships, and residual confounding cannot be ruled out. An important limitation is that this study does not account for the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on septic shock outcomes. The sharp rise in mortality during 2020–2021 may reflect a combination of factors including the direct effects of COVID-19 infections, as well as pandemic-related factors such as overwhelmed healthcare systems and delayed access to care. This gap represents an important avenue for future research. Lastly, the database is from the United States and may not be generalized to other countries.

In patients admitted with septic shock, significant racial disparities in mortality exist, which became attenuated when adjusting for comorbidities, AKI, AKI requiring dialysis, mechanical ventilation, socioeconomic status, and hospital level factors. These findings emphasize that the issue is multifactorial, and there are many drivers of these disparities, including social determinants of health and management of comorbidities, occur before patients develop the acuity of septic shock.

| 1. | Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, Colombara DV, Ikuta KS, Kissoon N, Finfer S, Fleischmann-Struzek C, Machado FR, Reinhart KK, Rowan K, Seymour CW, Watson RS, West TE, Marinho F, Hay SI, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Angus DC, Murray CJL, Naghavi M. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395:200-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2870] [Cited by in RCA: 4085] [Article Influence: 817.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Cecconi M, Evans L, Levy M, Rhodes A. Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet. 2018;392:75-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 810] [Cited by in RCA: 1393] [Article Influence: 199.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bauer M, Gerlach H, Vogelmann T, Preissing F, Stiefel J, Adam D. Mortality in sepsis and septic shock in Europe, North America and Australia between 2009 and 2019- results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24:239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 89.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lakbar I, Munoz M, Pauly V, Orleans V, Fabre C, Fond G, Vincent JL, Boyer L, Leone M. Septic shock: incidence, mortality and hospital readmission rates in French intensive care units from 2014 to 2018. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2022;41:101082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | De Backer D, Deutschman CS, Hellman J, Myatra SN, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Talmor D, Antonelli M, Pontes Azevedo LC, Bauer SR, Kissoon N, Loeches IM, Nunnally M, Tissieres P, Vieillard-Baron A, Coopersmith CM; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Research Committee. Surviving Sepsis Campaign Research Priorities 2023. Crit Care Med. 2024;52:268-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sterling SA, Miller WR, Pryor J, Puskarich MA, Jones AE. The Impact of Timing of Antibiotics on Outcomes in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1907-1915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Amrollahi F, Shashikumar SP, Meier A, Ohno-Machado L, Nemati S, Wardi G. Inclusion of social determinants of health improves sepsis readmission prediction models. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29:1263-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sheikh F, Douglas W, Diao YD, Correia RH, Gregoris R, Machon C, Johnston N, Fox-Robichaud AE; Sepsis Canada. Social determinants of health and sepsis: a case-control study. Can J Anaesth. 2024;71:1397-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Amrollahi F, Kennis BD, Shashikumar SP, Malhotra A, Taylor SP, Ford J, Rodriguez A, Weston J, Maheshwary R, Nemati S, Wardi G, Meier A. Prediction of Readmission Following Sepsis Using Social Determinants of Health. Crit Care Explor. 2024;6:e1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ang SP, Chia JE, Krittanawong C, Vummadi T, Deshmukh A, Usman MH, Lavie CJ, Mukherjee D. Racial disparities in trend, clinical characteristics and outcomes in Takotsubo syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024;49:102826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Mackey K, Ayers CK, Kondo KK, Saha S, Advani SM, Young S, Spencer H, Rusek M, Anderson J, Veazie S, Smith M, Kansagara D. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in COVID-19-Related Infections, Hospitalizations, and Deaths : A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:362-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 807] [Cited by in RCA: 784] [Article Influence: 196.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Macias Gil R, Marcelin JR, Zuniga-Blanco B, Marquez C, Mathew T, Piggott DA. COVID-19 Pandemic: Disparate Health Impact on the Hispanic/Latinx Population in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:1592-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 47.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ricardo AC, Chen J, Toth-Manikowski SM, Meza N, Joo M, Gupta S, Lazarous DG, Leaf DE, Lash JP; STOP-COVID Investigators. Hispanic ethnicity and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0268022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2016-2021. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available from: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. |

| 15. | Rinderknecht MD, Klopfenstein Y. Predicting critical state after COVID-19 diagnosis: model development using a large US electronic health record dataset. NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4:113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gaieski DF, Tsukuda J, Maddox P, Li M. Are Patients With an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition Discharge Diagnosis Code for Sepsis Different in Regard to Demographics and Outcome Variables When Comparing Those With Sepsis Only to Those Also Diagnosed With COVID-19 or Those With a COVID-19 Diagnosis Alone? Crit Care Explor. 2023;5:e0964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Law AC, Bosch NA, Song Y, Tale A, Lasser KE, Walkey AJ. In-Hospital vs 30-Day Sepsis Mortality at US Safety-Net and Non-Safety-Net Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2412873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Soto GJ, Martin GS, Gong MN. Healthcare disparities in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2784-2793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | DiMeglio M, Dubensky J, Schadt S, Potdar R, Laudanski K. Factors Underlying Racial Disparities in Sepsis Management. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mayr FB, Yende S, Linde-Zwirble WT, Peck-Palmer OM, Barnato AE, Weissfeld LA, Angus DC. Infection rate and acute organ dysfunction risk as explanations for racial differences in severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;303:2495-2503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Corl K, Levy M, Phillips G, Terry K, Friedrich M, Trivedi AN. Racial And Ethnic Disparities In Care Following The New York State Sepsis Initiative. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38:1119-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mayr FB, Yende S, D'Angelo G, Barnato AE, Kellum JA, Weissfeld L, Yealy DM, Reade MC, Milbrandt EB, Angus DC. Do hospitals provide lower quality of care to black patients for pneumonia? Crit Care Med. 2010;38:759-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McMaughan DJ, Oloruntoba O, Smith ML. Socioeconomic Status and Access to Healthcare: Interrelated Drivers for Healthy Aging. Front Public Health. 2020;8:231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 424] [Article Influence: 84.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vazquez Guillamet MC, Dodda S, Liu L, Kollef MH, Micek ST. Race Does Not Impact Sepsis Outcomes When Considering Socioeconomic Factors in Multilevel Modeling. Crit Care Med. 2022;50:410-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Esper AM, Moss M, Lewis CA, Nisbet R, Mannino DM, Martin GS. The role of infection and comorbidity: Factors that influence disparities in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2576-2582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ang SP, Chia JE, Iglesias J, Usman MH, Krittanawong C. Coronary Intervention Outcomes in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2025;27:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ndomba N, Soldera J. Management of sepsis in a cirrhotic patient admitted to the intensive care unit: A systematic literature review. World J Hepatol. 2023;15:850-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chebl RB, Tamim H, Sadat M, Qahtani S, Dabbagh T, Arabi YM. Outcomes of septic cirrhosis patients admitted to the intensive care unit: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e27593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Singbartl K, Kellum JA. AKI in the ICU: definition, epidemiology, risk stratification, and outcomes. Kidney Int. 2012;81:819-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Muiru AN, Yang J, Derebail VK, Liu KD, Feldman HI, Srivastava A, Bhat Z, Saraf SL, Chen TK, He J, Estrella MM, Go AS, Hsu CY; CRIC Study Investigators. Black and White Adults With CKD Hospitalized With Acute Kidney Injury: Findings From the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;80:610-618.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, Lo LJ, Hsu CY. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:37-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Abdelmalek FM, Angriman F, Moore J, Liu K, Burry L, Seyyed-Kalantari L, Mehta S, Gichoya J, Celi LA, Tomlinson G, Fralick M, Yarnell CJ. Association between Patient Race and Ethnicity and Use of Invasive Ventilation in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2024;21:287-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |