Published online Jun 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.98004

Revised: October 27, 2024

Accepted: December 10, 2024

Published online: June 9, 2025

Processing time: 257 Days and 11.4 Hours

Rhabdomyolysis (RML) as an etiological factor causing acute kidney injury (AKI) is sparsely reported in the literature.

To study the incidence of RML after surgical repair of an ascending aortic dissection (AAD) and to correlate with the outcome, especially regarding renal function. To pinpoint the perioperative risk factors associated with the deve

Retrospective single-center cohort study conducted in a tertiary cardiac center. We included all patients who underwent AAD repair from 2011-2017. Post-operative RML workup is part of the institutional protocol; studied patients were divided into two groups: Group 1 with RML (creatine kinase above cut-off levels 2500 U/L) and Group 2 without RML. The potential determinants of RML and impact on patient outcome, especially post

Out of 33 patients studied, 21 patients (64%) developed RML (Group RML), and 12 did not (Group non-RML). Demographic and intraoperative factors, notably body mass index, duration of surgery, and cardiopulmonary bypass, had no significant impact on the incidence of RML. Preoperative visceral/peripheral malperfusion, though not statistically significant, was higher in the RML group. A significantly higher incidence of renal complications, including de novo postoperative dialysis, was noticed in the RML group. Other morbidity parameters were also higher in the RML group. There was a significantly higher incidence of AKI in the RML group (90%) than in the non-RML group (25%). All four patients who required de novo dialysis belonged to the RML group. The peak troponin levels were significantly higher in the RML group.

In this study, we noticed a high incidence of RML after aortic dissection surgery, coupled with an adverse renal outcome and the need for post-operative dialysis. Prompt recognition and management of RML might improve the renal outcome. Further large-scale prospective trials are warranted to investigate the predisposing factors and influence of RML on major morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Core Tip: Renal complications contribute significantly to postoperative morbidity and mortality. Rhabdomyolysis (RML) is one of the etiological factors leading to tubular damage and acute kidney injury (AKI) perioperatively. There is no robust data on RML after ascending aortic dissection (AAD) surgery. Our single-center retrospective study, among AAD patients, evaluated the incidence of RML and its impact on renal outcome-We found a relatively high incidence (64%) of RML coupled with a higher rate of AKI and the need for renal replacement therapy. Further prospective studies are warranted to identify the risk factors of RML and its impact on outcomes.

- Citation: Sivadasan PC, Carr CS, Pattath ARA, Hanoura S, Sudarsanan S, Ragab HO, Sarhan H, Karmakar A, Singh R, Omar AS. Incidence and outcome of rhabdomyolysis after type A aortic dissection surgery: A retrospective analysis. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(2): 98004

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i2/98004.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.98004

Despite ongoing research, the etiology of acute kidney injury (AKI) remains incompletely understood, especially after aortic dissection surgeries. Omar et al[1] recently reported the association between rhabdomyolysis (RML) and AKI during cardiac surgery. However, there is no robust data regarding the same in aortic dissection surgeries specifically.

RML is a syndrome characterized by the breakdown of skeletal muscles and the release of toxic intracellular contents into the systemic circulation, causing damage to the renal tubules. Multiple factors are involved in the etiology of RML, predominantly direct trauma to muscles, as seen in crush injuries, burns, or prolonged muscle compression. It can also be associated with congenital disorders of metabolism, certain drugs (anesthetic agents, neuroleptic agents, and statins), infections, and sustained muscle contraction (seizures and prolonged exercise)[2]. Ischemia, followed by reperfusion of the muscle tissue, is a significant contributor to RML[3], which is relevant in the context of this study. The illness might vary in severity from asymptomatic elevations in markers of muscle injury [namely creatinine kinase (CK) and myo

AKI complicates recovery from cardiac surgery in up to 30% of patients and places them at a 5-fold increased risk of death during hospitalization. The etiology is often multifactorial, and preventive strategies are limited. AKI that requires RRT occurs in 2–5% of patients following cardiac surgery and is associated with a 50% mortality[8].

Aortic surgery is specifically associated with a higher incidence of renal complications than other types of cardiac surgery (with a reported incidence of AKI ranging from 18% to 55%)[9]. A significant number of patients with ascending aortic dissection (AAD) have chronic renal impairment on presentation[10]. The etiology of AKI post-AAD includes renal malperfusion, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, ischemia-reperfusion injury, hypertension, obesity, contrast-induced nephropathy, prolonged operation time, massive blood transfusion, and perioperative hypotension[11]. Renal failure and dialysis after aortic dissection surgery are independent predictors of mortality as per the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Perioperative predictors for postoperative AKI and RRT, according to various stu

In this retrospective study, we reviewed the charts of all patients who underwent surgical repair of type A aortic dissection from 2011 to 2017 in a tertiary care cardiac surgical center in Qatar. We obtained prior approval from the Insti

The patient data were collected anonymously from the electronic medical records using the prescribed data collection sheet. We included all patients who underwent AAD surgery except those who didn’t have a post-operative CK/myoglobin value. We also excluded patients with renal dysfunction before surgery.

In our center, the surgical and anesthetic techniques for AAD surgery follow a standard protocol. We use general anes

After systemic heparinization, arterial access for cardiopulmonary bypass is achieved through femoral, axillary, or ascending aortic cannulation (or a combination). A standard two-stage cannula is placed into the right atrium. Following initiation of cardiopulmonary bypass, the patients are cooled to 18-24 degrees centigrade. Depending on the anatomy of the dissection, the operations performed are a valved conduit with reimplantation of the coronary ostia or an inter

Following the surgical repair, complete de-airing, full rewarming, return of cardiac function, and acceptable metabolic parameters, cardiopulmonary bypass is weaned. Residual heparinization is reversed with protamine, and hemostasis is achieved. The administration of procoagulants and blood products is guided by rotational thromboelastometry to promote hemostasis. Inotrope/vasopressor usage is guided by echocardiography-derived cardiac output measurements, as well as arterial pressure readings. The patient is ventilated until the drainage is acceptable and other weaning criteria are satisfied.

It is our department protocol to estimate serum CK and myoglobin levels for all cardiac surgery patients, including aortic dissections, on the first day after surgery and to follow up on these values if they are significantly elevated.

Based on the highest value of CK recorded, our study divided patients into two groups – Group 1- with RML (CK above cut-off levels of 2500 U/L) and Group 2 without RML. The determinants of RML and the impact of the same on the outcome - predominantly renal function were evaluated. Collected data included preoperative and intraoperative variables potentially affecting the renal outcome and incidence of RML: Age, BMI, preoperative creatinine, statin use, the delay from onset of symptoms to surgical intervention, renal artery involvement, peripheral and visceral malperfusion, duration of surgery, bypass time, cross-clamp time, circulatory arrest time, propofol dosage, etc. We also collected data relating to patient outcomes in terms of mortality and morbidity indicators -focusing mainly on the renal outcome.

The primary objective of this study was to elucidate the incidence of RML following type A aortic dissection surgery and to correlate its severity with the patient outcome -primarily in terms of renal function. Other outcome measures included mechanical ventilation duration, length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay, duration of hospital stay, and mortality. We also proposed to formulate a risk-scoring system based on preoperative and intraoperative variables to predict the deve

We followed the same definition for RML used by Omar et al[1] in their study. In cardiac surgery, a higher cut-off value (2500 U/L) to diagnose RML is proposed to account for the release of CK from related myocardial injury[1]. Clinical indicators like dark urine, muscle pain, and fluctuation in serum potassium levels were not incorporated in the diagnostic criteria of RML, as these findings are relatively common in post-cardiac surgery settings as a sequela of cardiopulmonary bypass. The patients were divided into two groups based on this diagnostic cutoff: Group A with RML (highest CK value above 2500 U/L) and Group B without RML (highest CK below 2500 U/L). AKI was defined using the KDIGO criteria of AKI-KDIGO criteria which defined AKI as a 0.3 mg/dL (≥ 26.5 μmol/L) Serum Creatinine increase from baseline within 48 hours of surgery, a 1.5 times Serum Creatinine increase from baseline within 7 days of surgery[22]. The original KDIGO criteria also uses urine output below 0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 hours to define AKI. Urine output criteria were not used to define AKI, following the footsteps of a similar study[9]. Malperfusion was defined as symptoms, physical examination findings, or deranged laboratory results suggesting abnormal perfusion to visceral organs/ extremities[23].

Descriptive statistics were performed as mean and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequency and percentages for categorical variables. χ² tests were performed to see the association between the RML vs non-RML group and other independent categorical variables. Meanwhile, student t-tests (unpaired) were performed to see significant mean differences between the RML vs non-RML group with continuous variables. Levene's test for equality of variances was taken into consideration for P value. Correlation was performed between CK peak and change in creatinine μmol/liter. Likewise, the correlation was performed for myoglobin values vs change in creatinine and CK peak vs myoglobin. A correlation P value of 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered for a statistically significant level[24]. SPSS 22.0 statistical software was used for the analysis. Clinical and laboratory data were entered into a database (Microsoft Excel 97, Redmond, WA, United States), and statistical analyses were performed (Version 22, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

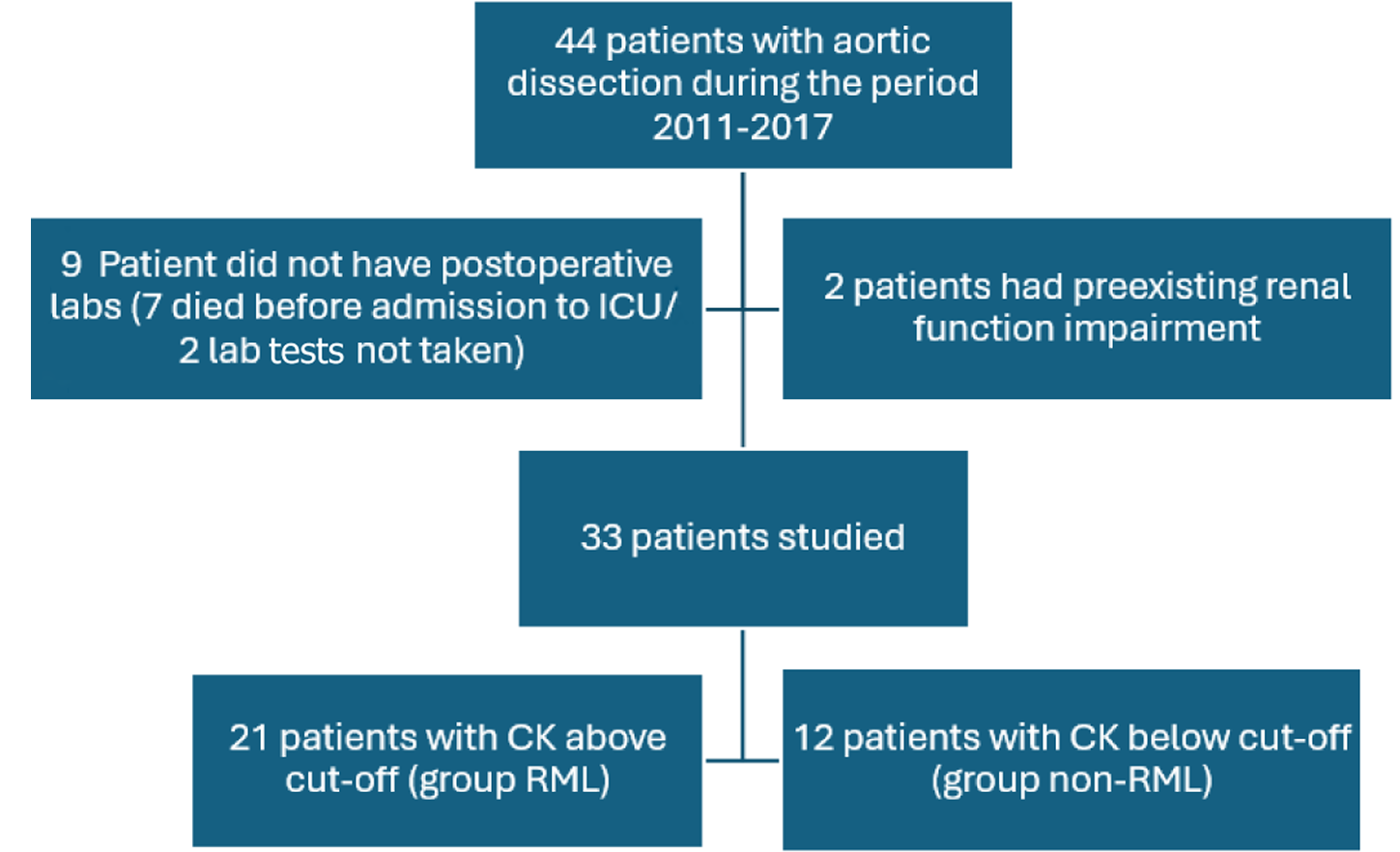

Forty-four patients underwent aortic dissection surgery in our center during the period 2011-2017. Out of these, seven patients died on the table, and two didn’t have post-op CK levels and hence were excluded from the study. Additionally, two patients with preexisting chronic kidney disease were also excluded. Of the remaining 33 patients, 21 patients (63.64%) developed RML based on our diagnostic cut-off value of CK (Group RML), and 12 did not (Group non-RML). The study design is summarized in Figure 1.

Other preoperative and intraoperative factors, like critical preoperative clinical status, congestive heart failure, cannulation method, type of surgical procedure, etc., did not have a significant impact on the incidence of RML postoperatively (Table 1). The RML group of patients had a higher BMI, though not statistically significant (P value 0.07). Of note, patients with a delayed presentation for surgery tend to develop RML less frequently than those presenting early (P value 0.03).

| Parameter | Group non-RML, n = 12 | Group RML, n = 21 | P value |

| Age | 46.75 ± 14.23 | 44.38 ± 11.87 | 0.56 |

| Sex: Female | 2 (16.7) | 1 (4.8) | 0.25 |

| Body mass index | 26.14 ± 3.33 | 32.08 ± 14.92 | 0.07 |

| Delay from the onset of symptoms to hospital admission | 52.81 ± 104.53 | 26.85 ± 33.67 | 0.03 |

| Preoperative Hb in gm/dL | 12.95 ± 1.86 | 13.41 ± 1.80 | 0.97 |

| Preoperative liver function (alanine aminotransferase) unit/liter | 47.33 ± 36.97 | 52.47 ± 39.77 | 0.76 |

| Preoperative ejection fraction | 48.80 ± 9.48 | 49.62 ± 7.07 | 0.81 |

| Preoperative cardiac arrest | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | 0.44 |

| Preop renal artery involvement by dissection | 3 (25) | 9 (43) | 0.30 |

| Preop peripheral/visceral malperfusion | 1 (8.3) | 6 (28.5) | 0.39 |

| Preoperative mechanical ventilation | 0 (0) | 1 (4.8) | 0.44 |

| Euroscore-logistic | 20.22 ± 14.83 | 16.27 ± 13.30 | 0.52 |

| Additive euroscore | 11.5 ± 3.46 | 11.05 ± 2.67 | 0.75 |

| Anesthesia time in minutes | 423.83 ± 73.34 | 495.57 ± 128.35 | 0.07 |

| Duration of surgery in minutes | 365.83 ± 70.13 | 433.6 ± 113.00 | 0.15 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time in minutes | 200.67 ± 66.11 | 213.43 ± 63.08 | 0.73 |

| Femoral Artery cannulation | 8 (73) | 13 (62) | 0.823 |

Analyzing the variables, it is apparent that almost all the patients who had a preoperative malperfusion belonged to the RML group (six patients) as against one patient in the non-RML group, the difference was not statistically significant (P value 0.39). Amongst the six malperfusion cases in the RML group, three had peripheral malperfusion, two had visceral, and one had combined visceral and peripheral malperfusion. One case in the non-RML group had peripheral malperfusion. The observed higher incidence of renal artery involvement by dissection in CT angiogram in the RML group also failed to reach statistical significance.

There were 2 ICU mortalities in the RML group, while there were none in the non-RML group, with the small number precluding statistical analysis for significance. AKI, as defined by KDIGO criteria, occurred in 22 patients out of 33 study patients (67% of patients). There was a significantly higher incidence of AKI in the RML group (90%) than in the non-RML group (25%), P = 0.002. The cumulative occurrence of de novo postoperative dialysis was 12% in the study po

| Parameter | Group non-RML | Group RML | P value |

| Peak creatinine in mmol/L | 113.25 ± 44.79 | 250.01 ± 165.50 | < 0.01 |

| Change in creatinine in mmol/L | 18.75 ± 30.04 | 124.33 ± 129.48 | < 0.01 |

| Peak troponin in ng/mL | 1243.23 ± 794.63 | 6257. 48 ± 9157.77 | < 0.01 |

| New acute kidney injury | 3 (25) | 19 (90) | < 0.01 |

| Mortality | 0 (0) | 2 (9.5) | 0.27 |

| Length of intensive care unit stay in hours | 92.83 ± 84.62 | 120.57 ± 124.73 | 0.45 |

| Length of hospital stay in days | 11.67 ± 6.38 | 16.52 ± 21.96 | 0.35 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation | 21.42 ± 25.52 | 36.68 ± 40.81 | 0.12 |

| Inotrope duration | 22.33 ± 24.86 | 37.04 ± 47.68 | 0.25 |

| New post-operative dialysis | 0 (0) | 4 (19.04) | 0.04 |

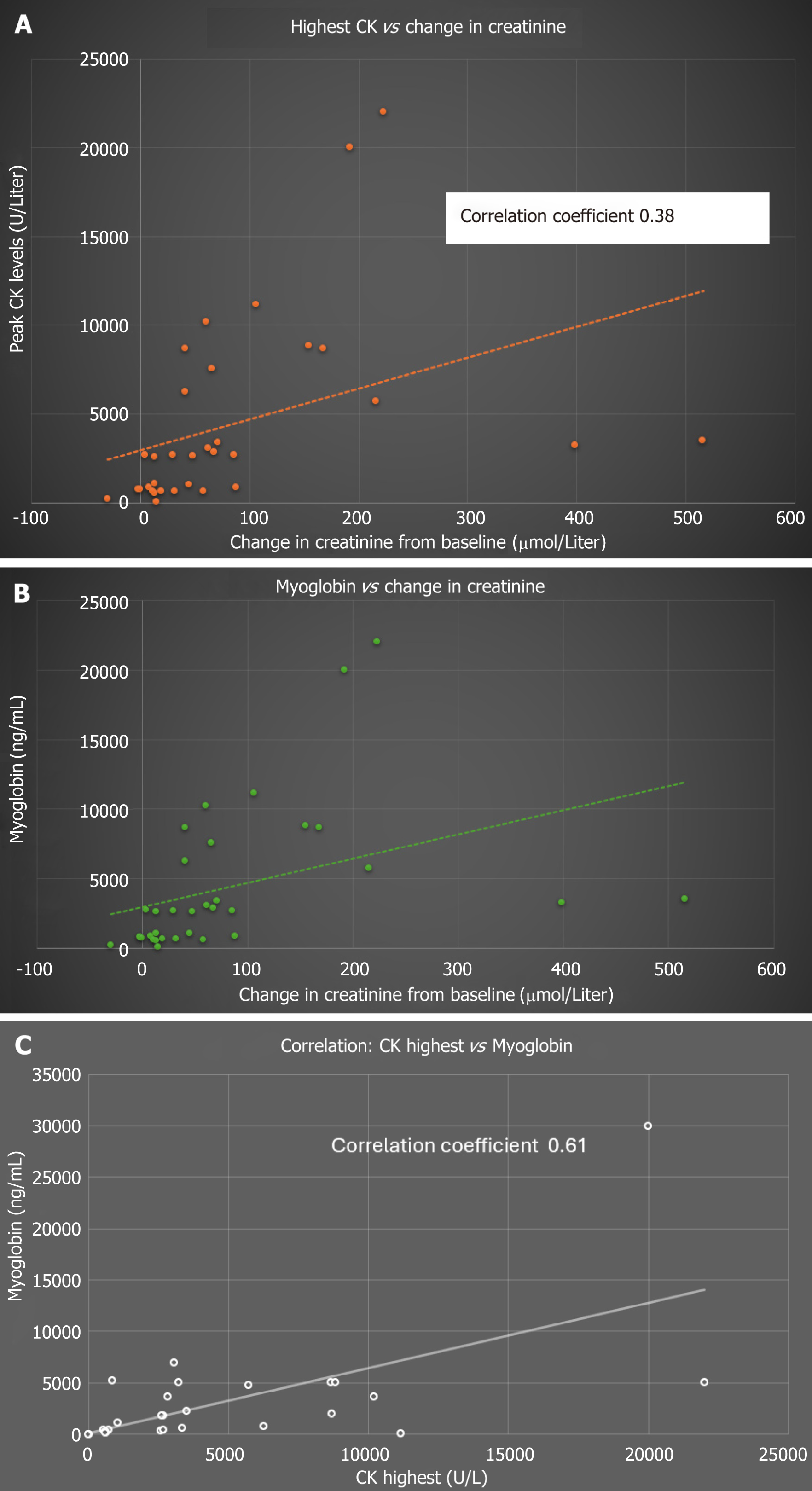

Figure 2A depicts the correlation between the change in creatinine in mmol/L (the difference between the peak creatinine and preoperative baseline) and the highest CK levels (U/L). Even though a significant correlation exists between the two (P = 0.0001), the correlation was not strong enough, as elicited by a Pearson coefficient of 0.38.

Figure 2B demonstrates the correlation between the change in creatinine in mmol/L (the difference between the peak creatinine and preoperative baseline) and postoperative myoglobin levels (ng/mL). A degree of correlation was noted (like the one observed with CK values) with a correlation coefficient of 0.28 (P = 0.0001).

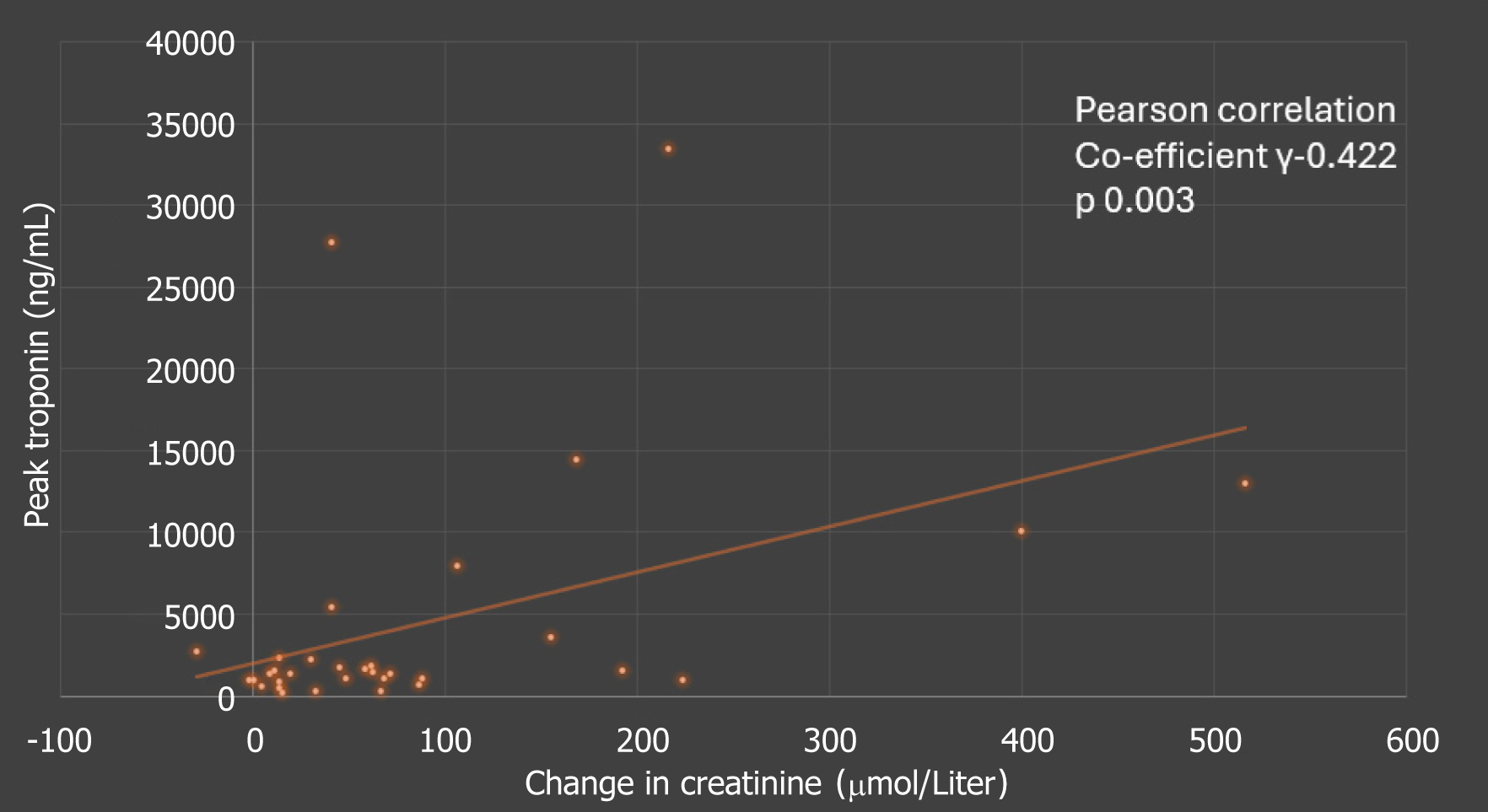

Figure 2C Demonstrates a near linear correlation between CK (U/L) and myoglobin levels (ng/mL) as expected -correlation coefficient 0.61 (P = 0.0001). Similarly, there was some weak correlation between the peak troponin levels and change in creatinine, as outlined in Figure 3.

The key findings of this study were: (1) Unusually high prevalence of RML amongst patients with AAD compared to other cardiac surgical patients; (2) Strong association of RML with AKI; (3) Patients with high BMI were more likely to develop RML (even though the association wasn’t statistically significant); (4) Higher occurrence of malperfusion in the RML group (again not to the level of statistical significance); and (5) Delayed presentation for surgery was associated with a lesser risk of RML. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies looked at these associations in Aortic Dissection Surgery.

Our study substantiates the hypothesis that aortic dissection surgery is associated with an unusually high incidence of RML (63%) compared to general cardiac surgical cases reported by Omar et al[1] (8.41%). The possible explanation for this predisposition could be occult ischemia to the lower limb following femoral cannulation, ischemia to paraspinal muscles due to malperfusion, and prolonged positioning due to a comparatively longer duration of the surgery[1,17]. It is pos

Miller et al[18], in an observational trial of 109 patients requiring thoracic/thoracoabdominal aortic repair, reported a dialysis requirement of 38% in the postoperative period. This study's dialysis rate was high, probably because of the liberal inclusion criteria used. Myoglobin levels were strongly predictive of postoperative renal dysfunction, which also agreed with our observations. However, this study was done in patients undergoing thoraco-abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery without the use of cardiopulmonary bypass. Still, risk factors like femoral cannulation and prolonged positioning associated with muscle damage are common in both patient cohorts. The same group has also reported the relationship between loss of Somato-Sensory Evoked Potential signals in the cannulated leg and adverse renal outcome, indicating leg ischemia as a potential contributing factor for RML[27].

The proposed risk factors for RML, like the presence of diabetes or hypertension, didn’t have a significant impact on the incidence of RML in our study. Femoral cannulation could theoretically be associated with a higher incidence of RML because of the potential for limb ischemia, but our study couldn’t demonstrate a difference in outcome in terms of RML with femoral cannulation.

Patients who developed RML were more obese compared to the non-RML group, but this difference failed to achieve statistical significance. Zhao et al[9] reported a higher incidence of AKI (66.7%) among obese patients with type A aortic dissection. They found elevated preoperative serum Creatinine level and 72-hour drainage volume as independent predictors of AKI, but they didn’t investigate the contribution of RML to the development of kidney injury. The asso

The incidence of AKI in our study population was 67%, which is slightly higher than that reported in the literature for AAD cases. It is noteworthy that the incidence of de novo postoperative dialysis (12%) in our study is comparable to the previous literature[12-14]. This difference in AKI incidence could be attributed to the variation in the definition of AKI used in various studies, surgical techniques, demographic characteristics, and institutional protocols for the initiation of CVVHD. Ko et al[12], in their study, which included 375 patients, reported an incidence of 44.0% AKI, out of which 9% required temporary dialysis and a further 3% progressed to end-stage renal disease. They also observed that the mortality and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events correlated significantly with the severity of AKI. Duration of Extracorporeal circulation, BMI, perioperative peak serum C-reactive protein concentration, renal malperfusion, and perioperative sepsis were found to be risk factors for AKI.

Imasaka et al[13], in their retrospective review, reported an incidence of 15.8% of RRT. The proposed risk factors for postoperative RRT were estimated glomerular filtration rate, coronary ischemic time, and total arch replacement. Sansone et al[14] observed a 37.8% incidence of AKI needing CVVHD after type A aortic dissection. Preoperative oliguria, longer Cardiopulmonary bypass /circulatory arrest times, and postoperative bleeding requiring a surgical revision were impli

One interesting observation from the study was that, despite using a higher cut-off value for CK to define RML (to account for the myocardial injury associated with cardiac surgery), we observed a significantly higher value of troponin in the RML group. This was not associated with other signs of myocardial damage, as evidenced by an insignificant difference in inotropic requirements (Table 2). This difference could be explained by the fact that in RML, cardiac enzymes may be elevated, unrelated to the degree of muscle damage[31-33]. Yet another explanation could be the higher incidence of AKI in the RML group. AKI is known to be associated with delayed clearance of troponins, as reported by Omar et al[34]. Myoglobin, as an alternative marker for RML, has the advantage of being unaffected by the degree of myocardial injury. However, the faster clearance from the circulation makes myoglobin less reliable than CK in quantifying RML[3,5]. Hence, it was not used as the primary marker of RML in our study.

Yet another finding that evolved from the review was that RML was more frequent in those patients who underwent early surgical intervention. One possible explanation could be that some degree of stabilization of perfusion is established as the disease progresses towards chronicity. Yet another possibility is some form of ischemic preconditioning, which offers protection against ischemia in chronic dissection cases[35]. However, we were not able to find any literature justifying this argument.

Interventions like aggressive fluid loading and forced diuresis titrated to a urine output of 200-300 mL/hour might help to mitigate the severity of renal failure in patients at risk of RML[5]. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, we were not able to assess the impact of these interventions on the renal outcome. However, considering the findings from our prior publication[1], we are focusing on the above line of management in patients at risk of RML, especially when there is unexplained hyperkalemia in the immediate postoperative period.

This study has several limitations- The sample size was small. The study was retrospective, which precluded further standardization of the design. We could not incorporate clinical indicators of RML in the diagnostic criteria due to the context of cardiac surgery. The study was not powered enough to do a multivariate analysis to investigate the risk factors for RML. We believe that a higher sample size would probably have enabled us to establish a significant association between malperfusion and RML.

In this study, we found a high incidence of RML after aortic dissection surgery, which paralleled an adverse renal outcome. Further large-scale prospective trials are warranted to investigate the predisposing factors (predominantly organ malperfusion) and influence of RML on major morbidity and mortality outcomes.

The authors are immensely indebted to all members of the Hamad Medical Corporation for fulfilling the requirements for research. The authors thank all members of the Cardiothoracic Surgery department, Cardiac Anesthesia and CTICU division, Heart Hospital, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar, for the required data and patient pool. The authors also thank every member of the medical research department of Hamad Medical Corporation for their support throughout this project. Our sincere thanks to Dr. Abulaziz Alkhulaifi, Chairman of the Cardiothoracic Surgery Department, for his administrative support.

| 1. | Omar AS, Ewila H, Aboulnaga S, Tuli AK, Singh R. Rhabdomyolysis following Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective, Descriptive, Single-Center Study. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:7497936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shapiro ML, Baldea A, Luchette FA. Rhabdomyolysis in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27:335-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huerta-Alardín AL, Varon J, Marik PE. Bench-to-bedside review: Rhabdomyolysis -- an overview for clinicians. Crit Care. 2005;9:158-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in RCA: 556] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Warren JD, Blumbergs PC, Thompson PD. Rhabdomyolysis: a review. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:332-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cote DR, Fuentes E, Elsayes AH, Ross JJ, Quraishi SA. A "crush" course on rhabdomyolysis: risk stratification and clinical management update for the perioperative clinician. J Anesth. 2020;34:585-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hofmann D, Buettner M, Rissner F, Wahl M, Sakka SG. Prognostic value of serum myoglobin in patients after cardiac surgery. J Anesth. 2007;21:304-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Benedetto U, Angeloni E, Luciani R, Refice S, Stefanelli M, Comito C, Roscitano A, Sinatra R. Acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting: does rhabdomyolysis play a role? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | O'Neal JB, Shaw AD, Billings FT 4th. Acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery: current understanding and future directions. Crit Care. 2016;20:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao H, Pan X, Gong Z, Zheng J, Liu Y, Zhu J, Sun L. Risk factors for acute kidney injury in overweight patients with acute type A aortic dissection: a retrospective study. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:1385-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mussa FF, Horton JD, Moridzadeh R, Nicholson J, Trimarchi S, Eagle KA. Acute Aortic Dissection and Intramural Hematoma: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016;316:754-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ma X, Li J, Yun Y, Zhao D, Chen S, Ma H, Wang Z, Zhang H, Zou C, Cui Y. Risk factors analysis of acute kidney injury following open thoracic aortic surgery in the patients with or without acute aortic syndrome: a retrospective study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;15:213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ko T, Higashitani M, Sato A, Uemura Y, Norimatsu T, Mahara K, Takamisawa I, Seki A, Shimizu J, Tobaru T, Aramoto H, Iguchi N, Fukui T, Watanabe M, Nagayama M, Takayama M, Takanashi S, Sumiyoshi T, Komuro I, Tomoike H. Impact of Acute Kidney Injury on Early to Long-Term Outcomes in Patients Who Underwent Surgery for Type A Acute Aortic Dissection. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:463-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Imasaka K, Tayama E, Tomita Y. Preoperative renal function and surgical outcomes in patients with acute type A aortic dissection†. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;20:470-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sansone F, Morgante A, Ceresa F, Salamone G, Patanè F. Prognostic Implications of Acute Renal Failure after Surgery for Type A Acute Aortic Dissection. Aorta (Stamford). 2015;3:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ghincea CV, Reece TB, Eldeiry M, Roda GF, Bronsert MR, Jarrett MJ, Pal JD, Cleveland JC Jr, Fullerton DA, Aftab M. Predictors of Acute Kidney Injury Following Aortic Arch Surgery. J Surg Res. 2019;242:40-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Qian SC, Ma WG, Pan XD, Liu H, Zhang K, Zheng J, Liu YM, Zhu JM, Sun LZ. Renal malperfusion affects operative mortality rather than late death following acute type A aortic dissection repair. Asian J Surg. 2020;43:213-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Anthony DG, Diaz J, Allen Bashour C, Moon D, Soltesz E. Occult rhabdomyolysis after acute type A aortic dissection. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1992-1994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Miller CC 3rd, Villa MA, Sutton J, Lau D, Keyhani K, Estrera AL, Azizzadeh A, Coogan SM, Safi HJ. Serum myoglobin and renal morbidity and mortality following thoracic and thoraco-abdominal aortic repair: does rhabdomyolysis play a role? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:388-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hiromasa S, Urabe T, Ishikawa T, Kaseno K, Nishimura M. Acute renal failure secondary to rhabdomyolysis associated with dissecting aortic aneurysm. Acta Cardiol. 1989;44:329-333. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ichikawa M, Tachibana K, Imanaka H, Takeuchi M, Takauchi Y, Inamori N. [Successful management of a patient with rhabdomyolysis and marked elevation of serum creatine kinase level]. Masui. 2005;54:914-917. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Cameron-Gagné M, Bédard L, Lafrenière-Bessi V, Lévesque MH, Dagenais F, Langevin S, Laflamme M, Voisine P, Jacques F. Buttocks Hard as Rocks: Not Wanted after Aortic Dissection Repair. Aorta (Stamford). 2018;6:37-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c179-c184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1436] [Cited by in RCA: 3327] [Article Influence: 255.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yang B, Patel HJ, Williams DM, Dasika NL, Deeb GM. Management of type A dissection with malperfusion. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;5:265-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Munro BH. Statistical methods for health care research fourth edition. Philadelphia, United States: University of Pennsylvania: Boston Collage Lipincott, 2001. |

| 25. | Czerny M, Siepe M, Beyersdorf F, Feisst M, Gabel M, Pilz M, Pöling J, Dohle DS, Sarvanakis K, Luehr M, Hagl C, Rawa A, Schneider W, Detter C, Holubec T, Borger M, Böning A, Rylski B. Prediction of mortality rate in acute type A dissection: the German Registry for Acute Type A Aortic Dissection score. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;58:700-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sandridge L, Kern JA. Acute descending aortic dissections: management of visceral, spinal cord, and extremity malperfusion. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;17:256-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Miller CC 3rd, Villa MA, Achouh P, Estrera AL, Azizzadeh A, Coogan SM, Porat EE, Safi HJ. Intraoperative skeletal muscle ischemia contributes to risk of renal dysfunction following thoracoabdominal aortic repair. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:691-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Youssef T, Abd-Elaal I, Zakaria G, Hasheesh M. Bariatric surgery: Rhabdomyolysis after open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a prospective study. Int J Surg. 2010;8:484-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chan JL, Imai T, Barmparas G, Lee JB, Lamb AW, Melo N, Margulies D, Ley EJ. Rhabdomyolysis in obese trauma patients. Am Surg. 2014;80:1012-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kato A, Ito E, Kamegai N, Mizutani M, Shimogushi H, Tanaka A, Shinjo H, Otsuka Y, Inaguma D, Takeda A. Risk factors for acute kidney injury after initial acute aortic dissection and their effect on long-term mortality. Ren Replace Ther. 2016;2:53. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Punukollu G, Gowda RM, Khan IA, Mehta NJ, Navarro V, Vasavada BC, Sacchi TJ. Elevated serum cardiac troponin I in rhabdomyolysis. Int J Cardiol. 2004;96:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Inbar R, Shoenfeld Y. Elevated cardiac troponins: the ultimate marker for myocardial necrosis, but not without a differential diagnosis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2009;11:50-53. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Li SF, Zapata J, Tillem E. The prevalence of false-positive cardiac troponin I in ED patients with rhabdomyolysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:860-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Omar AS, Mahmoud K, Hanoura S, Osman H, Sivadasan P, Sudarsanan S, Shouman Y, Singh R, AlKhulaifi A. Acute kidney injury induces high-sensitivity troponin measurement changes after cardiac surgery. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Twine CP, Ferguson S, Boyle JR. Benefits of remote ischaemic preconditioning in vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48:215-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |