Published online Jun 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.96624

Revised: January 11, 2025

Accepted: February 18, 2025

Published online: June 9, 2025

Processing time: 292 Days and 0.5 Hours

Valvular heart disease affects more than 100 million people worldwide and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The prevalence of at least moderate valvular heart disease is 2.5% across all age groups, but its prevalence increases with age. Mitral regurgitation and aortic stenosis are the most frequent types of valvular heart disease in the community and hospital context, res

We present a case of a 71-year-old female patient with a history of mitral valve replacement and warfarin anti-coagulation therapy. She was admitted to the intensive care unit due to spontaneously reperfused ischemic stroke of probable cardioembolic etiology. A dysfunctional mitral prosthesis was identified due to malfunction of one of the fixed discs. Furthermore, a possible microthrombotic lesion was suspected. Therefore, systemic thrombolysis was performed with subsequent normalization of mitral disc opening and closing.

This case underscores the critical importance of a multidisciplinary approach for timely decision-making in critically ill patients with prosthetic valve complications.

Core Tip: We describe the case of a 71-year-old woman with a history of mitral valve replacement who presented with car

- Citation: Barrios-Martínez DD, Pinzon YV, Giraldo V, Gonzalez G. Thrombolysis in dysfunctional valve and stroke. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(2): 96624

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i2/96624.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.96624

Heart valve disease affects more than 100 million people worldwide and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality[1]. The prevalence of at least moderate valvular heart disease is 2.5% and it increases with age. Mitral regurgitation and aortic stenosis are the most frequent types of valvular heart disease within the community and hospital settings, respectively[2]. Surgical valve replacement or mitral valve repair are the standard of care for valvular heart disease treatment[3]; however, prosthetic heart valve replacement can be associated with complications in either the peri- procedural phase or in the long-term follow-up period[4]. After prosthetic implantation, transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiography can detect valve dysfunction secondary to structural damage or thrombosis[5]. Prosthetic valve-associated thrombosis is a serious complication with a high mortality rate; the most common cause is inadequate anticoagulation therapy or other associated pathogenic factors, such as type of prosthesis and atrial fibrillation[6]. Although surgical treatment is usually preferred in cases of prosthetic valve-associated thrombosis, the optimal treatment approach remains controversial. The different therapeutic modalities available for prosthetic valve-associated thrombosis (heparin therapy, fibrinolysis, surgery) are largely influenced by the presence of valvular obstruction, valve location (left or right) and the patient’s clinical status[7].

We present herein the case of a 71-year-old female patient with a history of mitral valve replacement and warfarin anticoagulation therapy. She was admitted to the intensive care unit for neurological monitoring due to spontaneously reperfused ischemic stroke of probable cardioembolic etiology. A dysfunctional mitral prosthesis was documented due to malfunction of one of the fixed discs. Furthermore, a possible microthrombotic lesion was suspected, so systemic thrombolysis was considered through a multidisciplinary approach with subsequent normalization of the opening and closing of the mitral discs.

A 71-year-old woman consulted the emergency department with symptoms of nausea, somnolence and headache.

The patient presented with clinical symptoms over the course of 2 hours characterized by nausea, dizziness and intense headache, which did not improve with analgesic use such as acetaminophen.

The patient has a history of mechanical mitral valve replacement 20 years ago with regular echocardiographic follow-up, last performed a year before admission. Transthoracic echocardiograms documented a normofunctioning prosthetic with adequate transvalvular gradients.

Patient with a history of atrial fibrillation, warfarin use, and two cerebrovascular events in the last 3 years.

On presentation, the patient was in hypertensive crisis with a blood pressure of 186/90 mmHg and mitral holosystolic murmur. There were no signs of acute heart failure and no neurological findings. NIH Stroke Score, 0 points.

Blood work analysis suggested anemia (hemoglobin: 10.7 g%; normal range: 13-16 g%), leukocytosis (total leukocyte count: 13700; normal range: 4500-11000) with a shift to the left (75% neutrophils), and thrombocytosis (platelets: 4.14 × 105; normal range: 1.50-4.00 × 105). Liver and kidney function tests were within normal limits. The patient had a subtherapeutic international normalized ratio of 1.3 (therapeutic range: 2.0-3.0).

A simple cranial computed tomography (CT) scan was performed to rule out acute ischemic events and a cerebral magnetic resonance imaging showed right temporal punctate infarcts with recanalization, in addition to several old ischemic lesions.

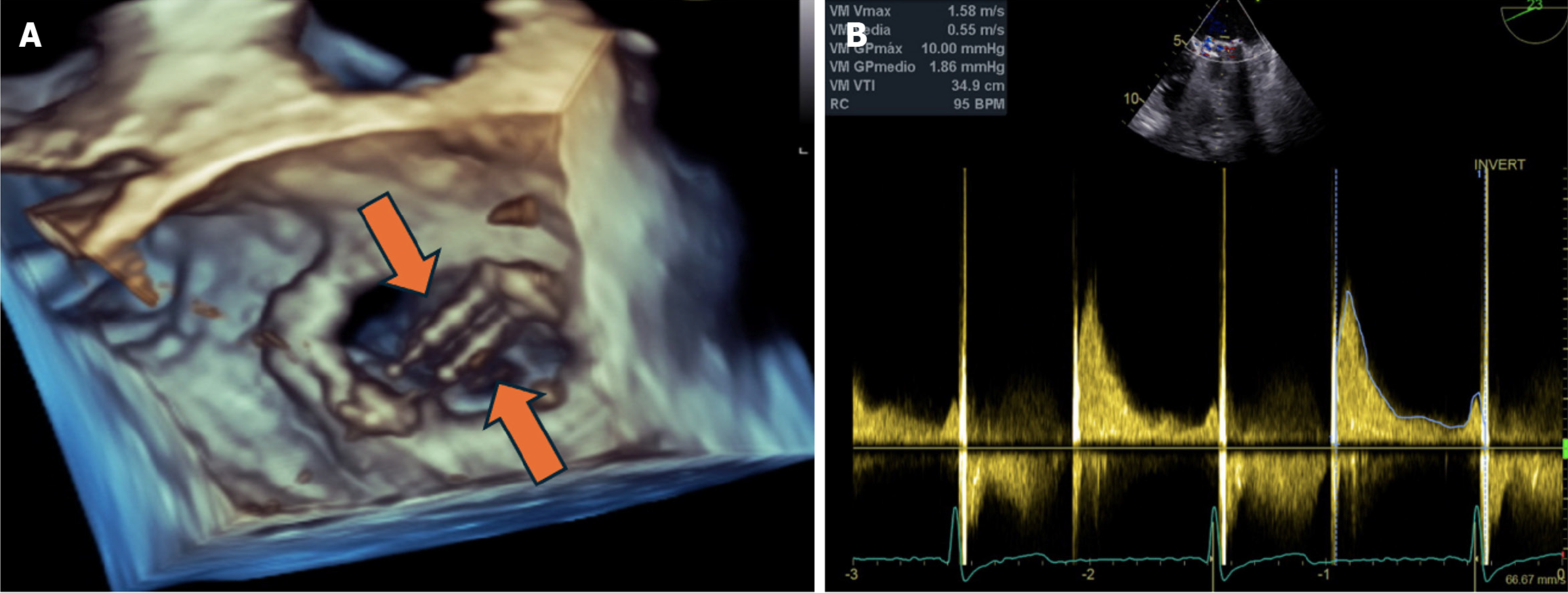

Transthoracic echocardiogram was initially performed and identified high transvalvular gradients, with a mean gradient of 6 mmHg. However, it did not allow for adequate visualization of the valve prosthesis. Therefore, a transesophageal echocardiogram was subsequently performed. Three-dimensional evaluation revealed a thickened prosthesis with altered mobility of one of the discs, generating an increase in transvalvular gradients and moderate insufficiency, compatible with thrombotic dysfunction (Figure 1).

Cardiology assessment was requested and, together with the neurocritical care service, thrombolysis was decided.

Cardioembolic etiology was suspected.

We consulted the Neurology and Critical Medicine Departments on thrombolysis as an alternative treatment to surgery. We requested a cardiology assessment, and together with the neurocritical care service decided to perform thrombolysis.

Prior to the procedure, warfarin reversal with prothrombin complex is required. We confirmed that there was no residual anticoagulant effect at the time of tissue plasminogen activator administration, which was administered at a dose of 0.9 mg/kg, the initial 10% as a bolus and the remaining infusion for 60 minutes. The infusion was completed without complications, without major bleeding nor changes in clinical status.

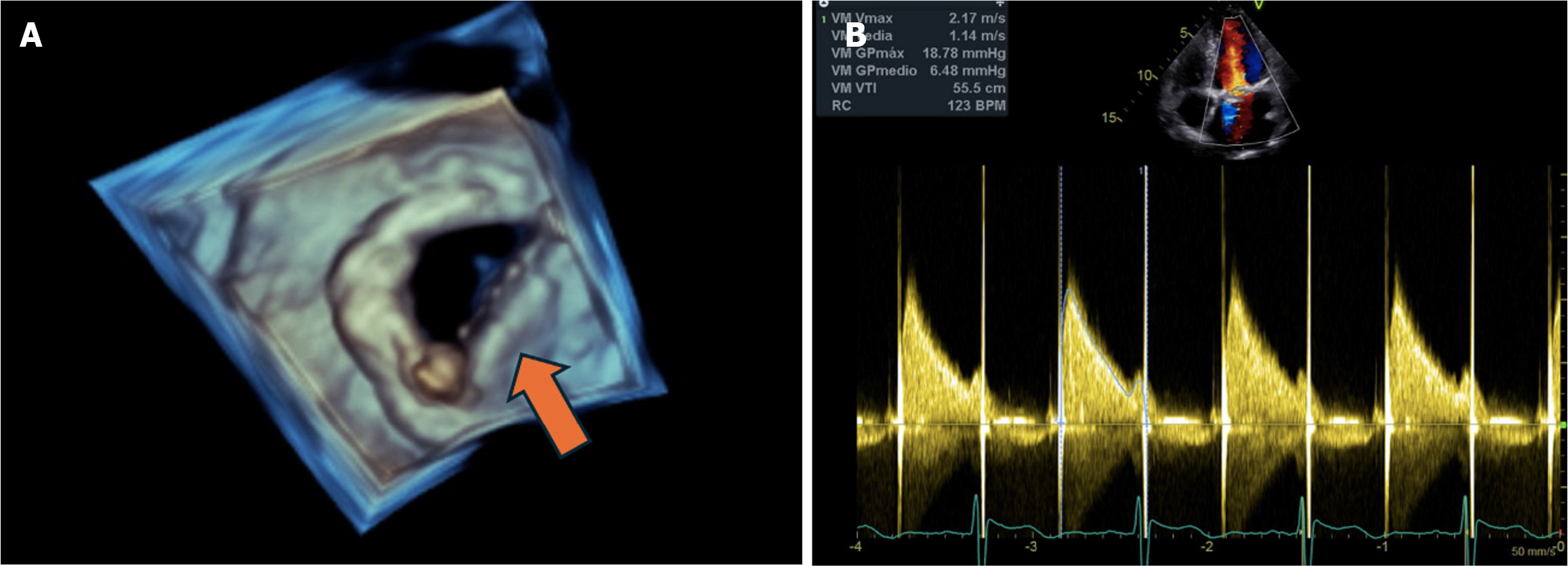

A transesophageal echocardiogram was performed 24 hours after thrombolysis and demonstrated normalization of the opening of the hemidiscs of the mitral valve prosthesis, reduction of the transvalvular gradients and reduction of the insufficiency to mild residual (Figure 2).

An additional CT scan of the skull showed no signs of bleeding. Anticoagulation therapy was restarted the day after thrombolysis.

The patient was transferred to a general hospital with adequate neurological evolution under anticoagulation therapy with unfractionated heparin. Warfarin was started for long-term anticoagulation and management of cardiovascular comorbidities. The patient was discharged without complications.

The worldwide incidence of prosthetic valve thrombosis is 0.03% in bioprosthetic valves, 0.5% to 8% in mechanical valves in the mitral and aortic positions, and up to 20% in mechanical tricuspid valves[8]. In contrast, a previous study found that 1.2% of patients in a 402 person cohort had mitral valve disease[9]. Periprosthetic valve-associated thrombosis is not very common but is one of the most frequent complications of mechanical or biological valve prostheses. Thrombotic phenomena account for 11% of valve dysfunction[10]. Another study by the same group found that in a study of 575 patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease, acute cardioembolic phenomena occurred in 16.3% of patients[11]. Mitral valve dysfunction can occur through several mechanisms: Reduced leaflet motion, impaired leaflet coaptation, leaflet thickening, reduction or enlargement of the prosthetic orifice, leading to stenosis or insufficiency. These changes cause disruptions to the transvalvular gradients that may or may not co-occur with other associated symptoms[12]. Although inadequate anticoagulation is the main cause of this phenomenon, other comorbidities or associated factors contribute, including atrial fibrillation, mechanical prostheses, and prosthesis location. Finally, thrombin generation can be induced through tissue factor and contact coagulation pathway activation, increasing thrombotic risk through proatherogenic and proinflammatory mechanisms[13].

Patients with prosthetic valve dysfunction with or without thrombosis may present with variable symptoms ranging from progressive dyspnea and signs of heart failure or systemic embolization. It is sometimes even asymptomatic with non-obstructive thrombi. These patients are at an increased risk of developing cerebral embolism, manifesting as tra

In this case study, our patient presented with a cardioembolic ischemic stroke. Echocardiogram analysis suggested that the stroke was caused by mitral mechanical prosthesis dysfunction with thrombotic lesion leading to mitral valve dysfunction. Left atrial thrombi are the most likely embolic source in these patients. Barbetseas et al[14] found that patients with ischemic stroke had a higher rate of mitral valve replacement and atrial fibrillation and increased left atrial size compared to patients with transient ischemic attack. However, none of these differences were statistically significant; the presence of left atrial thrombus, visualized by transesophageal echocardiography, was the only parameter that differentiated between patients with ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack.

Antithrombotic treatments indicated in prosthetic valve thrombosis and thromboembolic events after prosthetic heart valve replacement can be broadly classified according to their mechanisms of action as antiplatelet-based strategies (aspirin and/or a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor) and anticoagulant-based strategies [using vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) or direct oral anticoagulants][1].

VKAs are the primary preventative treatment against thrombosis due to prosthetic valve dysfunction, with dosing adjusted to maintain INRs of 2 to 3 and 2.5 to 3.5 for mechanical heart valves implanted in the aortic and mitral positions, respectively; for bioprosthetic heart valves, anticoagulation with VKA is recommended for the 1st 3 months after the procedure, with a target INR between 2.0 and 3.0, regardless of prosthesis position (aortic, mitral or right)[3,15,16].

In recent years, thrombolytic therapy has become an alternative to surgery in the treatment of obstructive prosthetic valve thrombosis[4]. Fibrinolytic therapy has a success rate of over 80%[15]. The appropriate management for obstructive prosthetic valve thrombosis has remained debatable. Some guidelines [e.g., European Society of Cardiology (ESC)] recommend surgery for all patients regardless of clinical status, while others (Heart Valve Disease Society) recommend thrombolytic therapy for all patients without contraindications[17,18]. However, the current update of the ESC/EACTS guidelines still considers surgery as the first-line approach[19].

Due to its high fibrin specificity, recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) is widely used in managing prosthetic heart valve thrombosis. However, streptokinase remains the drug of choice in low-income countries due to its relatively lower cost, while other agents such as tenecteplase and urokinase have also been used, with similar safety and efficacy compared to streptokinase[4,19].

The ESC guidelines recommend the standard dose (recombinant tissue plasminogen activator 10 mg bolus to 90 mg over 90 minutes with unfractionated heparin) of fibrinolytic therapy (class IIa) based on a meta-analysis of seven trials[20]. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines recommend the use of slow infusion, low-dose (25 mg tPA over 6 hours to 24 hours without bolus) fibrinolytic therapy as a comparable initial approach (Class I)[5]. Comparison of complication rates between the study groups showed a statistically lower combined complication rate in the slow infusion low-dose tPA group[21]. The ultra-slow PROMETEE trial demonstrated that ultra-slow (25 hours) infusion of low-dose (25 mg) tPA without bolus dosing is associated with fairly low non-fatal complications and mortality without loss of efficacy, except for those with NYHA class IV[22].

For a patient with prosthetic valve thrombosis, stroke may be the initial symptom resulting in cerebral embolism or may be secondary to thrombolysis therapy, with rates as high as 5%-6% for left-sided prosthetic heart valve thrombosis[23]. The recommended RTPA dose according to the ischemic stroke guideline is 0.9 mg/kg over 60 minutes, with a bolus of 10% of the total dose over 1 minute[24].

Simple cranial CT scan is essential to exclude intracranial hemorrhage and to define the administration of thrombolytic agents[25]. There are no protocols for thrombolytic therapy in patients presenting with stroke associated with cardiac valvular prosthesis. However, accelerated thrombolytic therapy regimens may complicate treatment[25]. In their case report, Özka et al[24] demonstrated that prolonged low-dose infusion of thrombolytic therapy and its continuation for the treatment of acute cerebral ischemic complications induced thrombolysis and limited the risk of hemorrhage and embolization. It resulted in subsequent normal mitral valve function with no evidence of residual thrombus, as assessed by echocardiography. However, there is no consensus on the best thrombolytic therapy strategy or specific agent. Therefore, thrombolysis in ischemic stroke associated with prosthetic heart valve thrombosis may be an effective therapy in selected cases[26].

We thank Dr. Nohra Piedad Romero Vanegas and the Echocardiography Service, Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe De Bogotá, Bogotá, Colombia. We also thank the Neurology Service, Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe De Bogotá, Bogotá, Colombia. During the final review and approval of the manuscript, our professor Jose del Carreño passed away. May he rest in peace.

| 1. | Dangas GD, Weitz JI, Giustino G, Makkar R, Mehran R. Prosthetic Heart Valve Thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2670-2689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huntley GD, Thaden JJ, Nkomo VT. Epidemiology of heart valve disease. Princ Heart Valve Eng. 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM 3rd, Thomas JD; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:2440-2492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 1077] [Article Influence: 97.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gündüz S, Kalçık M, Gürsoy MO, Güner A, Özkan M. Diagnosis, treatment & management of prosthetic valve thrombosis: the key considerations. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2020;17:209-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Singh M, Sporn ZA, Schaff HV, Pellikka PA. ACC/AHA Versus ESC Guidelines on Prosthetic Heart Valve Management: JACC Guideline Comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1707-1718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cáceres-Lóriga FM, Pérez-López H, Morlans-Hernández K, Facundo-Sánchez H, Santos-Gracia J, Valiente-Mustelier J, Rodiles-Aldana F, Marrero-Mirayaga MA, Betancourt BY, López-Saura P. Thrombolysis as first choice therapy in prosthetic heart valve thrombosis. A study of 68 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;21:185-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Roudaut R, Serri K, Lafitte S. Thrombosis of prosthetic heart valves: diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Heart. 2007;93:137-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Briët E. Thromboembolic and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Circulation. 1994;89:635-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 658] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pujadas Capmany R, Arboix A, Casañas-Muñoz R, Anguera-Ferrando N. Specific cardiac disorders in 402 consecutive patients with ischaemic cardioembolic stroke. Int J Cardiol. 2004;95:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Egbe AC, Pislaru SV, Pellikka PA, Poterucha JT, Schaff HV, Maleszewski JJ, Connolly HM. Bioprosthetic Valve Thrombosis Versus Structural Failure: Clinical and Echocardiographic Predictors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2285-2294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Arboix A, Massons J, García-Eroles L, Targa C, Parra O, Oliveres M. Trends in clinical features and early outcome in patients with acute cardioembolic stroke subtype over a 19-year period. Neurol India. 2012;60:288-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zoghbi WA, Chambers JB, Dumesnil JG, Foster E, Gottdiener JS, Grayburn PA, Khandheria BK, Levine RA, Marx GR, Miller FA Jr, Nakatani S, Quiñones MA, Rakowski H, Rodriguez LL, Swaminathan M, Waggoner AD, Weissman NJ, Zabalgoitia M; American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee; Task Force on Prosthetic Valves; American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Imaging Committee; Cardiac Imaging Committee of the American Heart Association; European Association of Echocardiography; European Society of Cardiology; Japanese Society of Echocardiography; Canadian Society of Echocardiography; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association; European Association of Echocardiography; European Society of Cardiology; Japanese Society of Echocardiography; Canadian Society of Echocardiography. Recommendations for evaluation of prosthetic valves with echocardiography and doppler ultrasound: a report From the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Task Force on Prosthetic Valves, developed in conjunction with the American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Imaging Committee, Cardiac Imaging Committee of the American Heart Association, the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, the Japanese Society of Echocardiography and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography, endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association, European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, the Japanese Society of Echocardiography, and Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:975-1014; quiz 1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 909] [Cited by in RCA: 966] [Article Influence: 60.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lip GYH, Collet JP, Caterina R, Fauchier L, Lane DA, Larsen TB, Marin F, Morais J, Narasimhan C, Olshansky B, Pierard L, Potpara T, Sarrafzadegan N, Sliwa K, Varela G, Vilahur G, Weiss T, Boriani G, Rocca B; ESC Scientific Document Group. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation associated with valvular heart disease: a joint consensus document from the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, endorsed by the ESC Working Group on Valvular Heart Disease, Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), South African Heart (SA Heart) Association and Sociedad Latinoamericana de Estimulación Cardíaca y Electrofisiología (SOLEACE). Europace. 2017;19:1757-1758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barbetseas J, Pitsavos C, Aggeli C, Psarros T, Frogoudaki A, Lambrou S, Toutouzas P. Comparison of frequency of left atrial thrombus in patients with mechanical prosthetic cardiac valves and stroke versus transient ischemic attacks. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:526-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Fleisher LA, Jneid H, Mack MJ, McLeod CJ, O'Gara PT, Rigolin VH, Sundt TM 3rd, Thompson A. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e1159-e1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1308] [Cited by in RCA: 1473] [Article Influence: 184.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Whitlock RP, Sun JC, Fremes SE, Rubens FD, Teoh KH. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for valvular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e576S-e600S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 484] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Butchart EG, Gohlke-Bärwolf C, Antunes MJ, Tornos P, De Caterina R, Cormier B, Prendergast B, Iung B, Bjornstad H, Leport C, Hall RJ, Vahanian A; Working Groups on Valvular Heart Disease, Thrombosis, and Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology, European Society of Cardiology. Recommendations for the management of patients after heart valve surgery. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2463-2471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Patil S, Setty N, Ramalingam R, Bedar Rudrappa MM, Manjunath CN. Study of prosthetic heart valve thrombosis and outcomes after thrombolysis. Int J Res Med Sci. 2019;7:1074. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, De Bonis M, Hamm C, Holm PJ, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Lansac E, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Rosenhek R, Sjögren J, Tornos Mas P, Vahanian A, Walther T, Wendler O, Windecker S, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2739-2791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4598] [Cited by in RCA: 4391] [Article Influence: 548.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Raman K, Mohanraj A, Palanisamy V, Ganesh J, Rawal S, Kurian VM, Sethuratnam R. Thrombolysis and surgery for mitral prosthetic valve thrombosis: 11-year outcomes. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2019;27:633-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Karthikeyan G, Senguttuvan NB, Joseph J, Devasenapathy N, Bahl VK, Airan B. Urgent surgery compared with fibrinolytic therapy for the treatment of left-sided prosthetic heart valve thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1557-1566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Özkan M, Gündüz S, Biteker M, Astarcioglu MA, Çevik C, Kaynak E, Yıldız M, Oğuz E, Aykan AÇ, Ertürk E, Karavelioğlu Y, Gökdeniz T, Kaya H, Gürsoy OM, Çakal B, Karakoyun S, Duran N, Özdemir N. Comparison of different TEE-guided thrombolytic regimens for prosthetic valve thrombosis: the TROIA trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:206-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Özkan M, Gündüz S, Gürsoy OM, Karakoyun S, Astarcıoğlu MA, Kalçık M, Aykan AÇ, Çakal B, Bayram Z, Oğuz AE, Ertürk E, Yesin M, Gökdeniz T, Duran NE, Yıldız M, Esen AM. Ultraslow thrombolytic therapy: A novel strategy in the management of PROsthetic MEchanical valve Thrombosis and the prEdictors of outcomE: The Ultra-slow PROMETEE trial. Am Heart J. 2015;170:409-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Özkan M, Gürsoy OM, Atasoy B, Uslu Z. Management of acute ischemic stroke occurred during thrombolytic treatment of a patient with prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis: continuing thrombolysis on top of thrombolysis. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2012;12:689-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Executive Committee; ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2008. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:457-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1738] [Cited by in RCA: 1698] [Article Influence: 99.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, Grubb RL, Higashida RT, Jauch EC, Kidwell C, Lyden PD, Morgenstern LB, Qureshi AI, Rosenwasser RH, Scott PA, Wijdicks EF; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Clinical Cardiology Council; American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council; Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Working Group; Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Circulation. 2007;115:e478-e534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 693] [Cited by in RCA: 678] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |