Published online Jun 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.101377

Revised: December 15, 2024

Accepted: January 3, 2025

Published online: June 9, 2025

Processing time: 168 Days and 0.1 Hours

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a critical condition characterized by acute hypoxemia, non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema, and decreased lung compliance. The Berlin definition, updated in 2012, classifies ARDS severity based on the partial pressure of arterial oxygen/fractional inspired oxygen fraction ratio. Despite various treatment strategies, ARDS remains a significant public health concern with high mortality rates.

To evaluate the implications of driving pressure (DP) in ARDS management and its potential as a protective lung strategy.

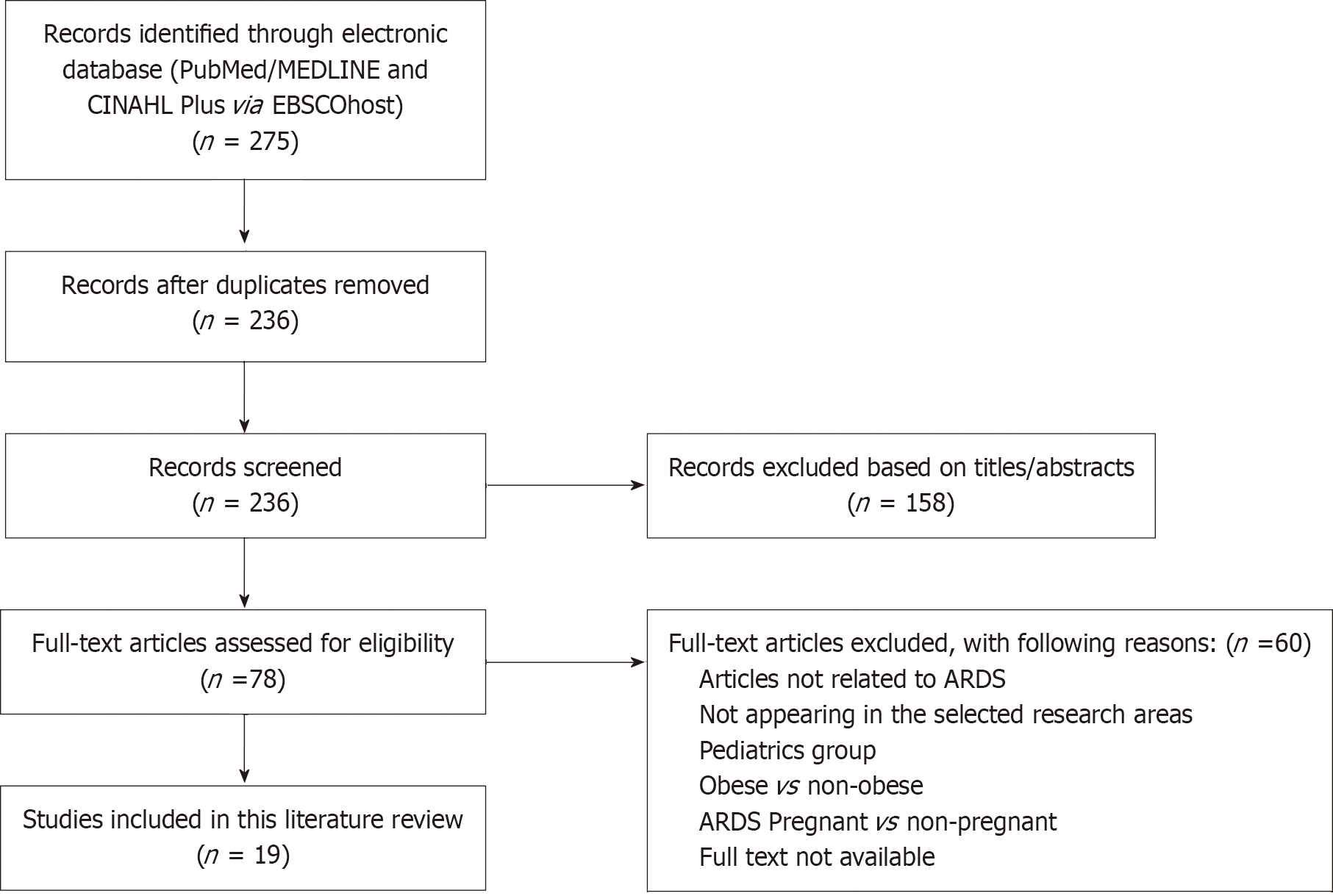

We conducted a systematic review using databases including EbscoHost, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, and Google Scholar. The search was limited to articles published between January 2015 and September 2024. Twenty-three peer-reviewed articles were selected based on inclusion criteria focusing on adult ARDS patients undergoing mechanical ventilation and DP strategies. The literature review was conducted and reported according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

DP, the difference between plateau pressure and positive end-expiratory pressure, is crucial in ARDS management. Studies indicate that lower DP levels are significantly associated with improved survival rates in ARDS patients. DP is a better predictor of mortality than tidal volume or positive end-expiratory pressure alone. Adjusting DP by optimizing lung compliance and minimizing overdistension and collapse can reduce ventilator-induced lung injury.

DP is a valuable parameter in ARDS management, offering a more precise measure of lung stress and strain than traditional metrics. Implementing DP as a threshold for safety can enhance protective ventilation strategies, po

Core Tip: This manuscript reviews the concept of monitoring driving pressure generated by mechanical ventilation to protect the lung. The literature demonstrated that driving pressure (DP) is a valuable parameter in acute respiratory distress syndrome management, offering a more precise measure of lung stress and strain than traditional metrics. Implementing DP as a threshold for safety can enhance protective ventilation strategies, potentially reducing mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Further research is needed to refine DP measurement techniques and validate its clinical application in diverse patient populations.

- Citation: Alzahrani HA, Corcione N, Alghamdi SM, Alhindi AO, Albishi OA, Mawlawi MM, Nofal WO, Ali SM, Albadrani SA, AlJuaid MA, Alshehri AM, Alzluaq MZ. Driving pressure in acute respiratory distress syndrome for developing a protective lung strategy: A systematic review. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(2): 101377

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i2/101377.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.101377

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was first discussed in a 1967 case-based study that described the clinical features in critically ill adults of acute hypoxemia, non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema, decreased lung compliance, elevated work of breathing, and the need for positive-pressure ventilation[1]. Pathological specimens from patients with ARDS often reveal diffuse alveolar damage. Laboratory studies have shown both alveolar epithelial and lung endothelial injury, resulting in an accumulation of protein-rich inflammatory edematous fluid in the alveolar space[2]. An American European consensus conference in 1992 created specific diagnostic criteria for the syndrome[3]. These criteria of ARDS were updated in 2012 and were denominated as the Berlin definition. It differs from the former American European Consensus definition by eliminating the term acute lung injury; it also excluded the requirement for wedge pressure < 18 and introduced the requirement of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) or continuous positive airway pressure of greater than or equivalent to 5 cmH2O[4]. The ratio of oxygen in the patient’s arterial blood to the fraction of the oxygen in the inspired air is used to diagnose ARDS. Partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2)/fractional inspired of oxygen (FiO2) ratio of these patients is less than 300[5].

The Berlin definition uses the PaO2/FiO2 ratio to distinguish mild (200-300 mmHg), moderate (100-200 mmHg), and severe (≤ 100 mmHg)[5]. ARDS is an acute disorder that begins within seven days of the inciting situation and is designated by bilateral lung infiltrates and severe progressive hypoxemia in the lack of any evidence of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. In addition, the Berlin definition was created to achieve more reliable diagnostic criteria that would aid in disease recognition and help align care choices and clinical outcomes based on the severity of the disease groups. ARDS diagnosis depends on clinical criteria solely because it is not feasible to obtain direct lung injury measurements by pathological specimens of lung tissue in most cases. Accordingly, neither distal airspace nor blood samples can be used to diagnose ARDS[2].

The emphasis on viability, reliability, and relevance during definition development; the implementation of an empiric assessment method in refining the definition; and the production of explicit illustrations to utilize the radiographic and origin of edema parameters are all significant incremental advances in this ARDS definition[6]. Berlin criteria are shown in Table 1. Epidemiologic research revealed that this clinical condition had a substantial effect in the United States, with 200000 cases each year associated with increased patient morbidity and healthcare costs[1]. Moreover, cellular damage in ARDS is distinguished by inflammation, apoptosis, necrosis, and increased alveolar-capillary permeability, which leads to the development of alveolar edema[7].

| Features | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Timing | Acute onset within one week of a known respiratory clinical insult or new/worsening respiratory symptoms | ||

| Hypoxemia | 200 < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 with PEEP or CPAP ≥ 5 cmH2O | 100 < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 with PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O | PaO2/FiO2 < 100 with PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O |

| Origin of edema | Respiratory failure is associated with known risk factors and is not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload. An objective assessment of cardiac failure or fluid overload is needed if no risk factor is present | ||

| Radiologic abnormalities | Bilateral opacities | Opacities involving at least three quadrants | |

| Additional physiological derangement | N/A | Crs < 40 mL/cmH2O1 | |

ARDS appeared to be a significant public health concern worldwide in a prospective study conducted in 459 intensive care units (ICUs) in 50 countries across five regions, with some geographical variation and very high mortality of approximately 40%[8]. Also, ARDS has been reported in 10.4% of total ICUs admissions and 23.4% of all patients requiring mechanical ventilation (MV)[8]. Since its first report in 1967, several studies have addressed various clinical aspects of the syndrome (risk factors, epidemiology, and treatment) and studies addressing its pathogenesis (underlying mechanisms, biomarkers, and genetic predisposition)[9].

Despite several randomized clinical trials to control the lung inflammatory response, the only proven method to consistently reduce mortality is a protective ventilation strategy[10]. An attractive method of setting tidal volume (VT) normalized to respiratory system compliance (Crs) proposed to be a predictor of survival than VT scaled to normal lung volume using predicted body weight (PBW)[11,12]. Driving pressure (DP) represents the difference between plateau pressure (Pplat) and PEEP and might be influenced by changes in VT or PEEP or Crs. Despite the correlation of DP and death rate in patients with ARDS, this relationship is less evident to non-ARDS patients[13]. Some authors recommended that DP was a goal in itself for ARDS management, implementing DP as a threshold for safety to reduce ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI)[14].

When treating the underlying pathology of ARDS, MV is the most effective method of reinstating or supporting optimal oxygenation and carbon dioxide removal requirements in patients with ARDS. ARDS patients’ lungs are highly susceptible to MV injury, widely known as VILI[15,16]. Consequently, an inappropriate MV approach leads to the development of VILI. The relative contributions to the development of the VILI are unclear as to the magnitude and frequency of mechanical stress and expiratory pressure[17]. This chain of events begins with mechanical injury to the lung tissue determined as the first hit by excess stress-induced strain, with subsequent barotrauma development as a response to the physical damage caused by excessive strain[18].

Thus, minimizing lung injury while ensuring adequate gas exchange (protective ventilation) is essential for ARDS to be safely managed clinically. There is currently widespread confusion concerning how best to perform protective ventilation in ARDS. Numerous strategies have been recommended and used, each with its rationale, advocates, and evidence of effectiveness[10]. Several ventilator strategies have been suggested for ARDS, such as lower VT, higher PEEP, and adjuncts such as prone positioning, neuromuscular blockade, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation[8]. However, the lung-protective ventilation technique suggested low VT, depending on optimal body weight and appropriate amounts of PEEP. Therefore, overstress and overstrain are not permanently reduced by lowering VT according to ideal body weight[19].

Numerous studies have been performed since the ARDS Net trials were published in 2000 to establish ventilation strategies to minimize or prevent VILI in patients with ARDS. Lowering the VT to 6 mL/kg of PBW was subsequently proven to improve the outcomes and reduce VILI incidence[20]. The goal of lung-protective MV strategies is to reduce the incidence of VILI. These strategies typically focus on delivering relatively low VT of 5-8 mL/kg of PBW and restricting Pplat to 30 cmH2O[20,21]. However, there is growing evidence showing that VILI can still be affected in patients with minimal aerated lung units available for ventilation, even when the VT is 6 mL/kg of PBW.

Ultimately, the Crs is linearly correlated to the “baby lung” dimensions, meaning that the ARDS lung is not “stiff” but small, with nearly normal intrinsic elasticity. Scientifically, the “baby lung” is a distinct anatomical structure in the nondependent lung regions. Nevertheless, the density redistribution in the prone position reveals that the “baby lung” is a functional and not an anatomical concept. This demonstrates conditions such as barotrauma and volutrauma and offers a rationale for the lung-protective strategy[22-24]. On the other hand, improved oxygenation has not consistently been shown to be an effective strategy for lowering mortality rates in ARDS patients[20]. However, lung stress and strain are more strongly correlated with outcomes and reflect VILI risk[22,25,26]. In 2015, the team of Amato et al[12] first began to seriously evaluate the effect of DP in treating ARDS patients with a meta-analysis of nine prospective trials involving 3500 patients with ARDS. The most remarkable conclusions from this data were that DP’s identification as an inde

This study employs a systematic literature review adhering to the PRISMA guidelines. We conducted comprehensive searches across electronic databases including EbscoHost, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, and Google Scholar, with the assistance of medical librarian experts. The search strategy incorporated key terms and Medical Subject Headings such as “Mechanical Ventilation”, “Driving Pressure”, “Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)”, and “Mortality”. The search was confined to articles published between January 2015 and September 2024 and limited to English-language publications.

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts, with a third reviewer available to resolve any disa

| Ref. | Title of the article | Objective of the article | Methodology of the article | Number of patients included in the article | Summary of the results | How driving pressure is described in the article | Mortality rate or mortality outcome mentioned in article | Effect of driving pressure on mortality |

| Gattinoni et al[22], 2006 | Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome | Studying lung recruitment in ARDS | Prospective study | Not specified | Lung recruitment beneficial for ARDS | Not described | Yes | Lung recruitment beneficial for ARDS |

| Meade et al[16], 2008 | Ventilation strategy using low tidal volumes, recruitment maneuvers, and high positive end-expiratory pressure for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: A randomized controlled trial | To study the effect of ventilation strategy on ARDS | Randomized controlled trial | Not specified | Low tidal volumes and high PEEP beneficial for ARDS | Not described | Yes | Low tidal volumes and high PEEP beneficial for ARDS |

| Mercat et al[21], 2008 | Positive end-expiratory pressure setting in adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: A randomized controlled trial | To study the effect of PEEP setting on ARDS | Randomized controlled trial | Not specified | High PEEP beneficial for ARDS | Not described | Yes | High PEEP beneficial for ARDS |

| Retamal et al[25], 2015 | High PEEP levels are associated with overdistension and tidal recruitment/derecruitment in ARDS patients | To study the effects of high PEEP levels on lung mechanics in ARDS patients | Prospective study | Not specified | High PEEP levels associated with overdistension and tidal recruitment/derecruitment | Not described | Yes | High PEEP levels associated with overdistension and tidal recruitment/derecruitment |

| Borges et al[28], 2015 | Altering the mechanical scenario to decrease the driving pressure | To study the effect of altering mechanical scenarios on DP | Prospective study | Not specified | Altering mechanical scenarios can decrease DP | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | Altering mechanical scenarios can decrease DP |

| Bellani et al[8], 2016 | Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries | To study the epidemiology and outcomes of ARDS | Prospective study | 459 ICUs | High mortality rate and geographical variation in ARDS | Not described | Yes | Not specified |

| Chiumello et al[19], 2016 | Airway driving pressure and lung stress in ARDS patients | To study the relationship between driving pressure and lung stress in ARDS | Retrospective study | 150 patients | DP correlated with lung stress | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | Driving pressure correlated with lung stress |

| Baedorf Kassis et al[31], 2016 | Mortality and pulmonary mechanics in relation to respiratory system and transpulmonary driving pressures in ARDS | To study the relationship between pulmonary mechanics and mortality in ARDS | Retrospective study | 150 patients | DP correlated with lung stress and mortality | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | DP correlated with lung stress and mortality |

| Guérin et al[33], 2016 | Effect of driving pressure on mortality in ARDS patients during lung protective mechanical ventilation in two randomized controlled trials | To study the effect of DP on mortality in ARDS | Randomized controlled trial | Not specified | DP correlated with mortality in ARDS | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | DP correlated with mortality in ARDS |

| Xie et al[29], 2017 | The effects of low tidal ventilation on lung strain correlate with respiratory system compliance | To study the effects of low tidal ventilation on lung strain | Prospective study | Not specified | Low tidal ventilation correlated with respiratory system compliance | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | Low tidal ventilation correlated with respiratory system compliance |

| Mezidi et al[36], 2017 | Effect of end-inspiratory plateau pressure duration on driving pressure | To study the effect of plateau pressure duration on DP | Prospective study | Not specified | Plateau pressure duration affects DP | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | Plateau pressure duration affects DP |

| Das et al[10], 2019 | What links ventilator driving pressure with survival in acute respiratory distress syndrome? | To study the link between ventilator driving pressure and survival in ARDS | Computational study | Not specified | Link between DP and survival | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | Driving pressure linked to survival |

| Collino et al[26], 2019 | Positive end-expiratory pressure and mechanical power | To study the effect of PEEP and mechanical power on ARDS | Prospective study | Not specified | High PEEP levels associated with overdistension and tidal recruitment/derecruitment | Not described | Yes | High PEEP levels associated with overdistension and tidal recruitment/derecruitment |

| Dai et al[32], 2019 | Risk factors for outcomes of acute respiratory distress syndrome patients: a retrospective study | To identify risk factors for ARDS outcomes | Retrospective study | Not specified | Identified risk factors for ARDS outcomes | Not described | Yes | Identified risk factors for ARDS outcomes |

| Bellani et al[37], 2019 | Driving pressure is associated with outcome during assisted ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome | To study the association of DP with outcomes during assisted ventilation in ARDS | Prospective study | Not specified | DP associated with outcomes during assisted ventilation in ARDS | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | DP associated with outcomes during assisted ventilation in ARDS |

| Yehya et al[30], 2021 | Response to ventilator adjustments for predicting ARDS mortality: Driving pressure versus oxygenation | To compare the predictive value of DP and oxygenation on ARDS mortality | Comparative study | Not specified | DP more informative about ventilator adjustments than oxygenation | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | DP more informative about ventilator adjustments than oxygenation |

| Dianti et al[17], 2021 | Comparing the effects of tidal volume, driving pressure, and mechanical power on mortality in trials of lung-protective mechanical ventilation | Comparing the effects of tidal volume, driving pressure, and mechanical power on mortality | Comparative study | Not specified | DP and mechanical power correlated with mortality | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | Driving pressure correlated with mortality |

| Goligher et al[35], 2021 | Effect of lowering VT on mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome varies with respiratory system elastance | To study the effect of lowering tidal volume on mortality in ARDS | Prospective study | Not specified | Lowering tidal volume beneficial for ARDS | Not described | Yes | Lowering tidal volume beneficial for ARDS |

| Costa et al[42], 2021 | Ventilatory variables and mechanical power in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome | To study ventilatory variables and mechanical power in ARDS | Prospective study | Not specified | Ventilatory variables and mechanical power associated with ARDS outcomes | Described as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Yes | Ventilatory variables and mechanical power associated with ARDS outcomes |

Adjustments was more strongly linked with lower mortality than improved PaO2/FiO2, making change in DP more informative about the advantage from ventilator adjustments. Since the Amato et al[12] in 2015 study, DP has been a significant area of concern in ARDS management in the past five years. The research had a multilevel mediation analysis that applied data from ARDS patients who participated in previously recorded randomized and controlled trials. Relatively low DP levels were significantly related to survival in ARDS patients[27], while survival was not inde

Transpulmonary DP, the pressure differential around the lung, must be considered when distinguishing lung from chest wall mechanics. Although measuring transpulmonary DP might be better to evaluate lung stress, an estimation of pleural pressure by using esophageal manometry is required. This measurement is not routinely implemented in most ICUs due to its laborious nature and some assumptions and limitations related to the technique[31]. Alternatively, DP is readily and promptly measured at the bedside, without the necessity for extra equipment or software. Two previous studies indicate for most patients, DP associates with transpulmonary DP and is a sufficient surrogate for lung stress[19,31].

Chiumello et al[19] in 2016 state that DP may vary from minimal variations (skinny patient, pneumonia) to a considerable overestimation (morbid obesity, abdominal hypertension) of transpulmonary DP. However, in the patient without spontaneous ventilatory activity, transpulmonary DP will always be lower than DP. For instance, it has been shown that DP correlates with lung stress and could be used to identify over-distension[19]. Hence, it appears logical to suspect that DP might be strongly associated with the risk of VILI so that the DP may be sufficient to detect lung overstress with acceptable accuracy[19]. Controlling VT without considering lung mechanics may be ineffective. New evidence strongly suggests that VT normalized to lung mechanics (e.g., VT/C) is a better predictor of mortality than VT dosage[28]. Amato et al[12] in 2015 stated that DP could be measured through the difference between Pplat and PEEP, “DP = Pplat - PEEP”. So, the Crs is measured as a ratio between VT and the DP. “Crs = VT/ (Pplat - PEEP) = VT/DP; DP = VT/ Crs”. Thus, The DP can be formulated as the ratio between VT and Crs resembling the lung and chest wall elastance.

As the equation indicates, a change in VT or pressure will impact the respiratory system’s Crs. A change in PEEP may likely minimize the stress associated with a VT (i.e., increase the Crs) if it will recruit non-aerated lung previously[11]. Amato and his colleagues hypothesized that if VT could be normalized to Crs rather than PBW, the impact of tidal ventilation could be calculated in a better way. That clearly shows that the ratio of VT/Crs represents the dynamic lung strain; it could be imprecise as the available lung volume is variable with the severity of ARDS[11]. The relationship between the airway DP (Pplat-PEEP) and transpulmonary DP (the difference between end-inspiratory transpulmonary pressure and end-expiratory transpulmonary pressure) is worth mentioning. Considering the chest wall’s elastance, such a variable can positively evaluate lung stress, which may be a safe technique to change MV support[19]. Therefore, adjusting VT through the available lung units by measuring DP can contribute to a more effective protective lung strategy in ARDS patients[12].

Chiumello et al[19] conducted a retrospective study of 150 heavily sedated and paralyzed ARDS patients recruited to a constant VT, respiratory rate (RR), and PEEP trial of 5 cmH2O and 15 cmH2O. At both PEEP levels, the higher DP group had significantly greater lung stress, respiratory system, and lung elastance than the lower DP group. More importantly, DP was significantly related to lung stress (transpulmonary pressure), and DP higher than 15 cmH2O and transpulmonary DP higher than 11.7 cmH2O, both measured at PEEP 15 cmH2O, were correlated with critical levels of stress. The only ventilation predictor linked to survival was airway DP, which has received a lot of attention after past findings by Amato et al[12] in 2015. DP was used as a surrogate for cyclic lung strain because it was the most accessible and easiest to measure. The amplitude of cyclic stretch is more closely related to cell and tissue damage than the maximum stretch level[32].

In critically ill patients with ARDS, the chest wall and abdomen play an unpredictable role in pleural pressure and respiratory system mechanics. As a result, a given PEEP can facilitate significantly different degrees of lung recruitment and distension in different patients. Moreover, airway pressure alone might not be enough to conduct lung-protective PEEP titration[31]. Therefore, if PEEP increases (with a constant VT) and DP decreases, this suggests a rise in Crs, and more non-aerated lung units are recruited via the higher PEEP. Likewise, if the DP increases and the Crs decrease with a rise in PEEP, it signifies that increased PEEP causes the aerated lung systems to overdistention. Accordingly, titrating PEEP to reduce DP can allow the clinician to reduce possible VILI.

However, since DP is mathematically coupled with VT and elastance, “causal mediation” does not provide a clear causal relation between setting a particular DP and the outcomes. As a result, a change in elastance after an intervention suggests a change in lung dynamics beyond a specific DP value setting. As recently shown by Guérin et al[33], when Pplat, VT, and PEEP are set within the close ranges of protective ventilation, DP does not give any additional benefit over indices of lung mechanics such as elastance Crs or Pplat. Indeed, independently from complex statistics, the best association between outcome and DP, instead of VT/kg PBW, is self-evident considering the correlation between the two variables: Elastance and VT. DP = VT × elastance. As revealed, Guérin et al[33] in 2016 suggest that the impact of DP on survival may be either due to elastance (severity of the disease) or VT (degree of strain). Another study revealed that DP and lung stress were closely linked. The optimal cutoff value for the DP was 15.0 cmH2O for lung stress greater than 24 cmH2O or 26 cmH2O, a level that has been associated with VILI[19]. Furthermore, other randomized controlled trials in patients with ARDS proved that besides Crs and Pplat, DP is an associated risk factor for elevated hospital mortality[33].

In ARDS, the mortality of ventilation with lower VT ventilation varies with respiratory system elastance, indicating that lung-protective ventilation strategies should focus on DP rather than VT[14,3]. Baedorf Kassis et al[31] reported ven

Several studies confirmed that DP values are significantly changed by how Pplat and PEEP are measured[31-33]. As intrinsic PEEP (autoPEEP) is frequently greater than PEEP in patients with ARDS, the standard calculation will overestimate DP if total PEEP is not considered[34], higher DP may induce lung damage[35]. Mezidi et al[36] in 2017 confirmed that alveolar recruitment maneuvers with increased PEEP levels decrease DP in patients responding to alveolar opening. Likewise, DP increases again when the patient begins with alveolar collapse, even maintaining the same VT.

Recent evidence suggests that lung mechanics (i.e., DP) should be used to titrate ventilation in ARDS patients rather than patient-based prescriptions (i.e., VT based on ideal body weight)[36-38]. However, regional characteristics of lung parenchyma may locally amplify (i.e., stress risers) the applied ventilation power and contribute to VILI[38]. Thus, small variations in VT or PEEP that result in a lower DP benefit can be considered protective for patients with acute respiratory failure or ARDS. The effect of DP in spontaneously breathing ARDS subjects has recently been investigated. The findings support the effectiveness of determining DP during assisted MV, and the authors notice that subjects with lower DP and higher Crs have a greater chance of surviving[38].

There was conflicting data regarding the additive prognostic advantage of DP beyond other pulmonary mechanics, such as Pplat and Crs, in confirmed ARDS cases. Amato et al[12] announced that DP was the most valuable ventilator parameter to treat ARDS because it was significantly associated with mortality. A study concluded that DP was also correlated with mortality, yet it provided the same information as Pplat[33]. Pplat predicted mortality better than DP in several studies[33]. For example, Villar et al[34], in their cohort of non-ARDS patients, indicated that fact. Measuring the Pplat correlated better with mortality than DP. Even in likely patients ventilated with a DP below 19 cmH2O, a Pplat strictly below 30 cmH2O would enable a significant reduction in mortality, a greater effect than that of a DP below 19 cmH2O when the Pplat was already below 30 cmH2O.

The PEEP level with the least overdistention and collapse does not always correspond to the best respiratory system Crs, particularly when tidal recruitment is affected by repetitive opening and closing of collapsed alveoli and small airways within atelectatic areas. Using DP separately may neglect the role of PEEP in treating and managing patients on ventilatory support. For instance, although a theoretically “safe” level of DP of 14 cmH2O, it could become harmful if PEEP is 20 cmH2O or 0 cmH2O[34,35]. Besides, using Crs could help clinicians easily recognize subjects at lower or higher risk of being exposed to “safe” or “unsafe” lung strain levels. However, higher DP may induce lung injury more easily in patients with low Crs[35]. Despite the possibility of reducing DP in patients with ARDS may improve survival rate, an accurate measurement of DP could be challenging in clinical settings. Furthermore, inaccuracies in ventilator pressure measurements and the role of spontaneous breathing efforts in the management of ARDS contribute to the clinical question about how to calculate and titrate DP at the bedside optimally[36].

In a secondary review of the lung safe study (2016), researchers investigated the predictors associated with beneficial outcomes in 2377 ARDS patients who underwent MV[37]. According to the authors, optimal DP, higher PEEP level, and lower RR were valid predictors to improve ARDS survival[37]. In another study, Pplat, DP, and Crs can be evaluated at the bedside during spontaneous breathing trials. Also, the data suggested that both higher DP and lower Crs are associated with more mortality[38].

In 2018, a systematic review and meta-analysis research observed that higher DP was associated with a significantly higher mortality rate in the meta-analysis of four studies of 3252 patients. The median DP between the higher and lower groups (interquartile range) was 15 cmH2O[11]. At the same time, high DP was related to increased mortality in patients requiring pressure support ventilation mode. Non-survivors had a higher DP than survivors, but it was just one cmH2O where non-survivors had lower static Crs[39]. In adjusted analyses, a pooled database of 4549 ARDS patients who had enrolled in six randomized clinical trials and one large observational cohort of ARDS patients confirmed that DP was a significant predictor of mortality. Interestingly, during controlled MV in ARDS, mechanical power was associated with mortality, but a simplified model using DP and RR was equivalent[39].

Researchers in 2015 identified DP as an independent factor correlated with survival in patients with ARDS[12]. Their study demonstrated that lower DP levels were significantly associated with improved survival rates in ARDS patients. Similarly, another study in 2021 found that reduced DP following protocolized ventilator adjustments was more strongly linked with lower mortality than improvements in the PaO2/FiO2 ratio[30]. A meta-analysis conducted in 2018 conducted involving 3252 patients and observed that higher DP was associated with a significantly higher mortality rate[11]. Further researcherconfirmed these findings by showing that DP was a significant predictor of mortality in ARDS[40,41].

A study in 2015 suggested that active modification of the lung “mechanical scenario” through lung recruiting and PEEP selection could reduce DP[28]. This approach involves redistributing VT from overextended to recruited lung regions, thereby decreasing overdistension and improving lung Crs. Another retrospective study of 150 heavily sedated and paralyzed ARDS patients, finding that higher DP was significantly related to greater lung stress and mortality[19]. Additional study confirmed that DP values are significantly influenced by how Pplat and PEEP are measured[31]. Intrinsic PEEP (auto-PEEP) can overestimate DP if total PEEP is not considered. Further research reported that alveolar recruitment maneuvers with increased PEEP levels decrease DP in patients responding to alveolar opening, although DP increases again when the patient begins with alveolar collapse[28-41].

Researchers in 2015 explained that DP can be measured through the difference between Pplat and PEEP[12]. The Crs of the respiratory system is measured as a ratio between VT and DP. Adjusting VT through available lung units by mea

The findings from this review highlight the critical role of DP in the management of ARDS. The review emphasizes that lower DP is significantly associated with improved survival rates in ARDS patients. The physiological basis of DP, noting that it represents the pressure differential around the lung. While measuring transpulmonary DP might offer a more accurate assessment of lung stress, it is often impractical in clinical settings due to the need for esophageal manometry. Instead, DP can be readily measured at the bedside, making it a practical surrogate for lung stress in most patients.

With regards to the relationship between DP and lung mechanics, it is indicating that DP is a better predictor of mortality than VT alone. This is because DP accounts for the Crs of the respiratory system, which varies among patients. The review highlights that controlling VT without considering lung mechanics may be ineffective, and adjusting VT based on DP can lead to more effective lung-protective ventilation strategies. Several challenges in measuring and interpreting DP are noted. For instance, intrinsic PEEP (autoPEEP) can lead to overestimation of DP if not properly accounted for. Additionally, the variability in chest wall and abdominal mechanics among critically ill patients can affect DP measurements. Also, DP is a valuable parameter, and it should not be used in isolation but rather in conjunction with other indices of lung mechanics such as elastance and Pplat.

The clinical evidence underscores the importance of DP as a critical parameter in the management of ARDS. Lower DP is consistently associated with better survival outcomes, making it a valuable target for lung-protective ventilation strategies. While there are challenges in measuring and interpreting DP, its practical applicability at the bedside makes it a useful tool for clinicians. Future research should continue to refine our understanding of DP and its role in optimizing ventilation strategies for ARDS patients. Integrating DP with other indices of lung mechanics can enhance the precision of ventilatory support and improve patient outcomes.

| 1. | Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1685-1693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2636] [Cited by in RCA: 2797] [Article Influence: 139.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Matthay MA, Zemans RL, Zimmerman GA, Arabi YM, Beitler JR, Mercat A, Herridge M, Randolph AG, Calfee CS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 913] [Cited by in RCA: 1575] [Article Influence: 262.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4145] [Cited by in RCA: 4158] [Article Influence: 134.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Diamond M, Peniston HL, Sanghavi DK, Mahapatra S. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. 2024 Jan 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Papazian L, Aubron C, Brochard L, Chiche JD, Combes A, Dreyfuss D, Forel JM, Guérin C, Jaber S, Mekontso-Dessap A, Mercat A, Richard JC, Roux D, Vieillard-Baron A, Faure H. Formal guidelines: management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 77.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, Antonelli M, Anzueto A, Beale R, Brochard L, Brower R, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, Rhodes A, Slutsky AS, Vincent JL, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ranieri VM. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1573-1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1051] [Cited by in RCA: 964] [Article Influence: 74.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3976] [Cited by in RCA: 3860] [Article Influence: 154.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, Ranieri M, Rubenfeld G, Thompson BT, Wrigge H, Slutsky AS, Pesenti A; LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA. 2016;315:788-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2627] [Cited by in RCA: 3600] [Article Influence: 400.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ashbaugh DG, Bigelow DB, Petty TL, Levine BE. Acute respiratory distress in adults. Lancet. 1967;2:319-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2410] [Cited by in RCA: 2241] [Article Influence: 38.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Das A, Camporota L, Hardman JG, Bates DG. What links ventilator driving pressure with survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome? A computational study. Respir Res. 2019;20:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aoyama H, Pettenuzzo T, Aoyama K, Pinto R, Englesakis M, Fan E. Association of Driving Pressure With Mortality Among Ventilated Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Amato MB, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, Brochard L, Costa EL, Schoenfeld DA, Stewart TE, Briel M, Talmor D, Mercat A, Richard JC, Carvalho CR, Brower RG. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:747-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1397] [Cited by in RCA: 1606] [Article Influence: 160.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Schmidt MFS, Amaral ACKB, Fan E, Rubenfeld GD. Driving Pressure and Hospital Mortality in Patients Without ARDS: A Cohort Study. Chest. 2018;153:46-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goligher EC, Ferguson ND, Brochard LJ. Clinical challenges in mechanical ventilation. Lancet. 2016;387:1856-1866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Spieth PM, Gama de Abreu M. Lung recruitment in ARDS: we are still confused, but on a higher PEEP level. Crit Care. 2012;16:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Meade MO, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Slutsky AS, Arabi YM, Cooper DJ, Davies AR, Hand LE, Zhou Q, Thabane L, Austin P, Lapinsky S, Baxter A, Russell J, Skrobik Y, Ronco JJ, Stewart TE; Lung Open Ventilation Study Investigators. Ventilation strategy using low tidal volumes, recruitment maneuvers, and high positive end-expiratory pressure for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:637-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 887] [Cited by in RCA: 873] [Article Influence: 51.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dianti J, Matelski J, Tisminetzky M, Walkey AJ, Munshi L, Del Sorbo L, Fan E, Costa EL, Hodgson CL, Brochard L, Goligher EC. Comparing the Effects of Tidal Volume, Driving Pressure, and Mechanical Power on Mortality in Trials of Lung-Protective Mechanical Ventilation. Respir Care. 2021;66:221-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Umbrello M, Marino A, Chiumello D. Tidal volume in acute respiratory distress syndrome: how best to select it. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chiumello D, Carlesso E, Brioni M, Cressoni M. Airway driving pressure and lung stress in ARDS patients. Crit Care. 2016;20:276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8487] [Cited by in RCA: 8333] [Article Influence: 333.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 21. | Mercat A, Richard JC, Vielle B, Jaber S, Osman D, Diehl JL, Lefrant JY, Prat G, Richecoeur J, Nieszkowska A, Gervais C, Baudot J, Bouadma L, Brochard L; Expiratory Pressure (Express) Study Group. Positive end-expiratory pressure setting in adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:646-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 846] [Cited by in RCA: 850] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M, Chiumello D, Ranieri VM, Quintel M, Russo S, Patroniti N, Cornejo R, Bugedo G. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1775-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 977] [Cited by in RCA: 960] [Article Influence: 50.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gattinoni L, Pesenti A. The concept of “baby lung”. In: Pinsky M, Brochard L, Hedenstierna G, Antonelli M, editors. Applied Physiology in Intensive Care Medicine 1. Berlin: Springer, 2021: 289–297. |

| 24. | Gattinoni L, Marini JJ, Pesenti A, Quintel M, Mancebo J, Brochard L. The "baby lung" became an adult. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:663-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Retamal J, Bugedo G, Larsson A, Bruhn A. High PEEP levels are associated with overdistension and tidal recruitment/derecruitment in ARDS patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2015;59:1161-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Collino F, Rapetti F, Vasques F, Maiolo G, Tonetti T, Romitti F, Niewenhuys J, Behnemann T, Camporota L, Hahn G, Reupke V, Holke K, Herrmann P, Duscio E, Cipulli F, Moerer O, Marini JJ, Quintel M, Gattinoni L. Positive End-expiratory Pressure and Mechanical Power. Anesthesiology. 2019;130:119-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Laffey JG, Bellani G, Pham T, Fan E, Madotto F, Bajwa EK, Brochard L, Clarkson K, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Heunks LM, Kurahashi K, Laake JH, Larsson A, McAuley DF, McNamee L, Nin N, Qiu H, Ranieri M, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Wrigge H, Slutsky AS, Pesenti A; LUNG SAFE Investigators and the ESICM Trials Group. Potentially modifiable factors contributing to outcome from acute respiratory distress syndrome: the LUNG SAFE study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1865-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Borges JB, Hedenstierna G, Larsson A, Suarez-Sipmann F. Altering the mechanical scenario to decrease the driving pressure. Crit Care. 2015;19:342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Xie J, Jin F, Pan C, Liu S, Liu L, Xu J, Yang Y, Qiu H. The effects of low tidal ventilation on lung strain correlate with respiratory system compliance. Crit Care. 2017;21:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yehya N, Hodgson CL, Amato MBP, Richard JC, Brochard LJ, Mercat A, Goligher EC. Response to Ventilator Adjustments for Predicting Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Mortality. Driving Pressure versus Oxygenation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18:857-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Baedorf Kassis E, Loring SH, Talmor D. Mortality and pulmonary mechanics in relation to respiratory system and transpulmonary driving pressures in ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1206-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dai Q, Wang S, Liu R, Wang H, Zheng J, Yu K. Risk factors for outcomes of acute respiratory distress syndrome patients: a retrospective study. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:673-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Guérin C, Papazian L, Reignier J, Ayzac L, Loundou A, Forel JM; investigators of the Acurasys and Proseva trials. Effect of driving pressure on mortality in ARDS patients during lung protective mechanical ventilation in two randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2016;20:384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Villar J, Herrán-Monge R, González-Higueras E, Prieto-González M, Ambrós A, Rodríguez-Pérez A, Muriel-Bombín A, Solano R, Cuenca-Rubio C, Vidal A, Flores C, González-Martín JM, García-Laorden MI; Genetics of Sepsis (GEN-SEP) Network. Clinical and biological markers for predicting ARDS and outcome in septic patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:22702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Goligher EC, Costa ELV, Yarnell CJ, Brochard LJ, Stewart TE, Tomlinson G, Brower RG, Slutsky AS, Amato MPB. Effect of Lowering Vt on Mortality in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Varies with Respiratory System Elastance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:1378-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Mezidi M, Yonis H, Aublanc M, Lissonde F, Louf-Durier A, Perinel S, Tapponnier R, Richard JC, Guérin C. Effect of end-inspiratory plateau pressure duration on driving pressure. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:587-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Russotto V, Bellani G, Foti G. Respiratory mechanics in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bellani G, Grassi A, Sosio S, Gatti S, Kavanagh BP, Pesenti A, Foti G. Driving Pressure Is Associated with Outcome during Assisted Ventilation in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2019;131:594-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Loring SH, Malhotra A. Driving pressure and respiratory mechanics in ARDS. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:776-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chen Z, Wei X, Liu G, Tai Q, Zheng D, Xie W, Chen L, Wang G, Sun JQ, Wang S, Liu N, Lv H, Zuo L. Higher vs. Lower DP for Ventilated Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Emerg Med Int. 2019;2019:4654705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Pelosi P, Ball L. Should we titrate ventilation based on driving pressure? Maybe not in the way we would expect. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Costa ELV, Slutsky AS, Brochard LJ, Brower R, Serpa-Neto A, Cavalcanti AB, Mercat A, Meade M, Morais CCA, Goligher E, Carvalho CRR, Amato MBP. Ventilatory Variables and Mechanical Power in Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204:303-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 49.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |