Published online Jun 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.100844

Revised: January 8, 2025

Accepted: February 8, 2025

Published online: June 9, 2025

Processing time: 183 Days and 6.2 Hours

The burden of cannabis use disorder (CUD) in the context of its prevalence and subsequent cardiopulmonary outcomes among cancer patients with severe sepsis is unclear.

To address this knowledge gap, especially due to rising patterns of cannabis use and its emerging pharmacological role in cancer.

By applying relevant International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes to the National Inpatient Sample database between 2016-2020, we identified CUD(+) and CUD(-) arms among adult cancer admissions with severe sepsis. Comparing the two cohorts, we examined baseline demo

We identified a total of 743520 cancer patients admitted with severe sepsis, of which 4945 had CUD. Demographically, the CUD(+) cohort was more likely to be younger (median age = 58 vs 69, P < 0.001), male (67.9% vs 57.2%, P < 0.001), black (23.7% vs 14.4%, P < 0.001), Medicaid enrollees (35.2% vs 10.7%, P < 0.001), in whom higher rates of substance use and depression were observed. CUD(+) patients also exhibited a higher prevalence of chronic pulmonary disease but lower rates of cardiovascular comorbidities. There was no significant difference in major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events between CUD(+) and CUD(-) cohorts on multivariable regression analysis. However, the CUD(+) cohort had lower all-cause mortality (adjusted odds ratio = 0.83, 95% confidence interval: 0.7-0.97, P < 0.001) and respiratory failure (adjusted odds ratio = 0.8, 95% confidence interval: 0.69-0.92, P = 0.002). Both groups had similar median length of stay, though CUD(+) patients were more likely to have higher hospital cost compared to CUD(-) patients (median = 94574 dollars vs 86615 dollars, P < 0.001).

CUD(+) cancer patients with severe sepsis, who tended to be younger, black, males with higher rates of substance use and depression had paradoxically significantly lower odds of all-cause in-hospital mortality and respiratory failure. Future research should aim to better elucidate the underlying mechanisms for these observations.

Core Tip: Cannabis use disorder (CUD) in cancer patients with severe sepsis is associated with lower in-hospital mortality and respiratory failure despite higher rates of substance use and depression. CUD(+) patients, who are more likely to be younger, male, and black, also face increased hospital costs. These findings highlight the complex interplay between CUD and sepsis outcomes in cancer, suggesting the need for further research into the mechanisms behind these observations.

- Citation: Sager AR, Desai R, Mylavarapu M, Shastri D, Devaprasad N, Thiagarajan SN, Chandramohan D, Agrawal A, Gada U, Jain A. Cannabis use disorder and severe sepsis outcomes in cancer patients: Insights from a national inpatient sample. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(2): 100844

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i2/100844.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i2.100844

Cannabis use disorder (CUD) is defined by a set of diagnostic criteria, including patterns of gradually increasing intake, craving, unsuccessful attempts to limit use, disruptions in social and professional obligations, use in settings that pose physical harm, and the development of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms[1]. A meta-analysis of 21 studies identified that cannabis users have a one in five risk of developing CUD, and weekly or more frequent use increased the risk of cannabis dependence to one in three[2]. A study of Veterans Health Administration patients between 2005 and 2019 showed an increased prevalence of CUD over 14 years, from 1.38% to 2.25% in states where cannabis is not legal, 1.38% to 2.54% in states with medical cannabis laws only, and 1.40% to 2.56% in states with medical cannabis and recreational cannabis laws. However, the impact that legalization by state laws played on this up-trending pattern of use is relatively small and inconsistent across age groups, with the authors citing other possible factors like a concurrent rise in psy

Among cancer patients as well, age seems to play a role in cannabis use and perceptions about availability and risk. One study identified significantly higher use rates among those with past or recent cancer diagnosis in the middle age population compared to those without cancer, whereas this effect was not observed in younger or older age groups. Cousins et al[4] reported that 8.9% of total cancer patients and 9.9% of cancer patients who had been diagnosed in the past year had reported cannabis use. In general, increasing perceived risk and difficulty in access seemed to be a function of increasing age[4]. There are several approved cannabis-based medications on the market targeting a wide variety of cancer-related issues like chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, fatigue, anorexia, and chronic pain[5]. A study among 2970 patients with advanced cancer between 2015 and 2017 showed 95.9% of patients reported improvement in palliative symptoms with cannabis use at six-month follow-up[6]. In 2019, the American Cancer Society estimated 1.7 million new cancer diagnoses and more than 600000 deaths[7]. Hence, advancing novel therapeutic modalities to address this morbidity and mortality burden is imperative.

In recent years, the anticancer effects of cannabis have been explored more. Some researchers have noted its potential for modulating tumor growth in several in vitro and in vivo models, though this effect seems to be dependent on the type of cancer and drug dosage[8]. For example, a 2021 meta-analysis of 34 studies revealed a negative association between non-testicular cancer and cannabis use, though this study was notable for a high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 79.2%), obscuring the interpretation of its results[9]. Sepsis arises secondary to a dysregulation in the host response to infection, causing end-organ compromise that is life-threatening[10-12]. The incidence of sepsis or severe sepsis in cancer is variable in the literature. One large database study that included 29795 severe sepsis admissions with cancer found an overall incidence of 16.4 cases per 1000[13]. Another study found that across 19 million hospitalizations for sepsis between 2008 and 2017, one in five had concurrent cancer, with 80% of those being solid cancers[14]. Common sources are pulmonary, genitourinary, and abdominal, with gram-negative organisms like E. coli being most commonly encountered[15,16]. The rate of sepsis-related readmission appears higher in the cancer cohort vs the non-cancer cohort (6.2% vs 5.4%, P < 0.001)[17]. A 2013-2014 study of the United States National Readmissions Database found higher rates of in-hospital mortality among cancer-related sepsis admissions vs non-cancer-related sepsis (27.9% vs 19.5%, P < 0.001). Sepsis survivors also appear to have higher rates of all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events at long-term follow-up[18]. In contrast, a retrospective analysis of 20975 admissions between 2003 and 2014 demonstrated an improving trend in sepsis-associated mortality in cancer patients compared to those without cancer [adjusted (odds ratio) = 0.53, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.45-0.63][19]. There is insufficient data on the impact of CUD on severe sepsis and subsequent cardiopulmonary outcomes in cancer patients, which we have studied and intend to provide a basis for further research on this topic.

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) is part of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Qualities Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. We utilized the 2016-2020 dataset for our study. It is the largest public, all-payer dataset, and weighted survey analysis of the NIS datasets produces results that are representative estimates of the national outcomes[20]. As this database is de-identified to protect patient confidentiality, Institutional Review Board approval is not needed.

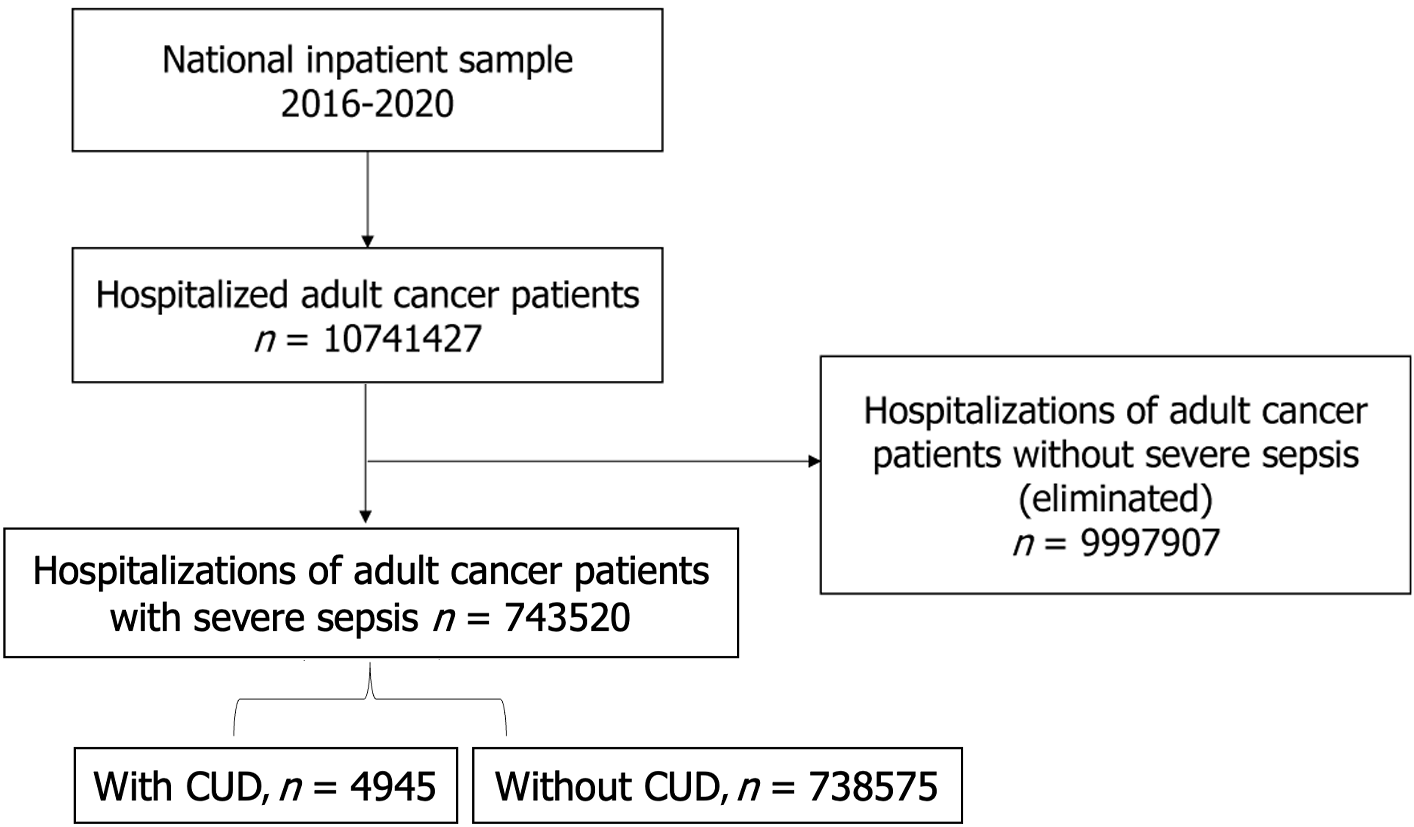

The study utilized the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnostic codes F12.1x and F12.2x (excluding F12.21 for dependence in remission) to identify cases of CUD, and R65.2x to identify cases of severe sepsis. The Revised Clinical Classifications Software was used to identify our two cohorts among all adult cancer patients admitted with severe sepsis between 2016 and 2020; specifically, the group with CUD(+) and the group without CUD(-)[21,22]. Both primary and secondary discharge diagnoses of severe sepsis and CUD were considered in distributing our cohorts (Figure 1).

Between the two cohorts, we compared patient demographics, hospital-specific features, and comorbidities among cancer patients admitted with severe sepsis. Primary outcomes were the prevalence and trends in CUD, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, and respiratory failure. Secondary outcomes were the hospital length of stay, cost, and impact on the utilization of healthcare resources.

IBM SPSS statistics (Version 25.0) with weighted data and complex sample modules with strata and cluster designs were used for our statistical analysis [IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows (Version 25.0) Armonk, NY: IBM Corp]. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and continuous variables were expressed as medians with ranges between the 25th and 75th percentile. We used Pearson-chi squared test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous non-normally distributed variables. Statistical significance was set at a P value of less than 0.05. Multivariable regression analysis was used to analyze primary outcomes after adjusting for age, sex, race, median household income, payer type, hospital bed size, hospital location and teaching status, hospital region and patient comorbidities. Results of this regression analysis were expressed as adjusted OR with 95%CI and P values.

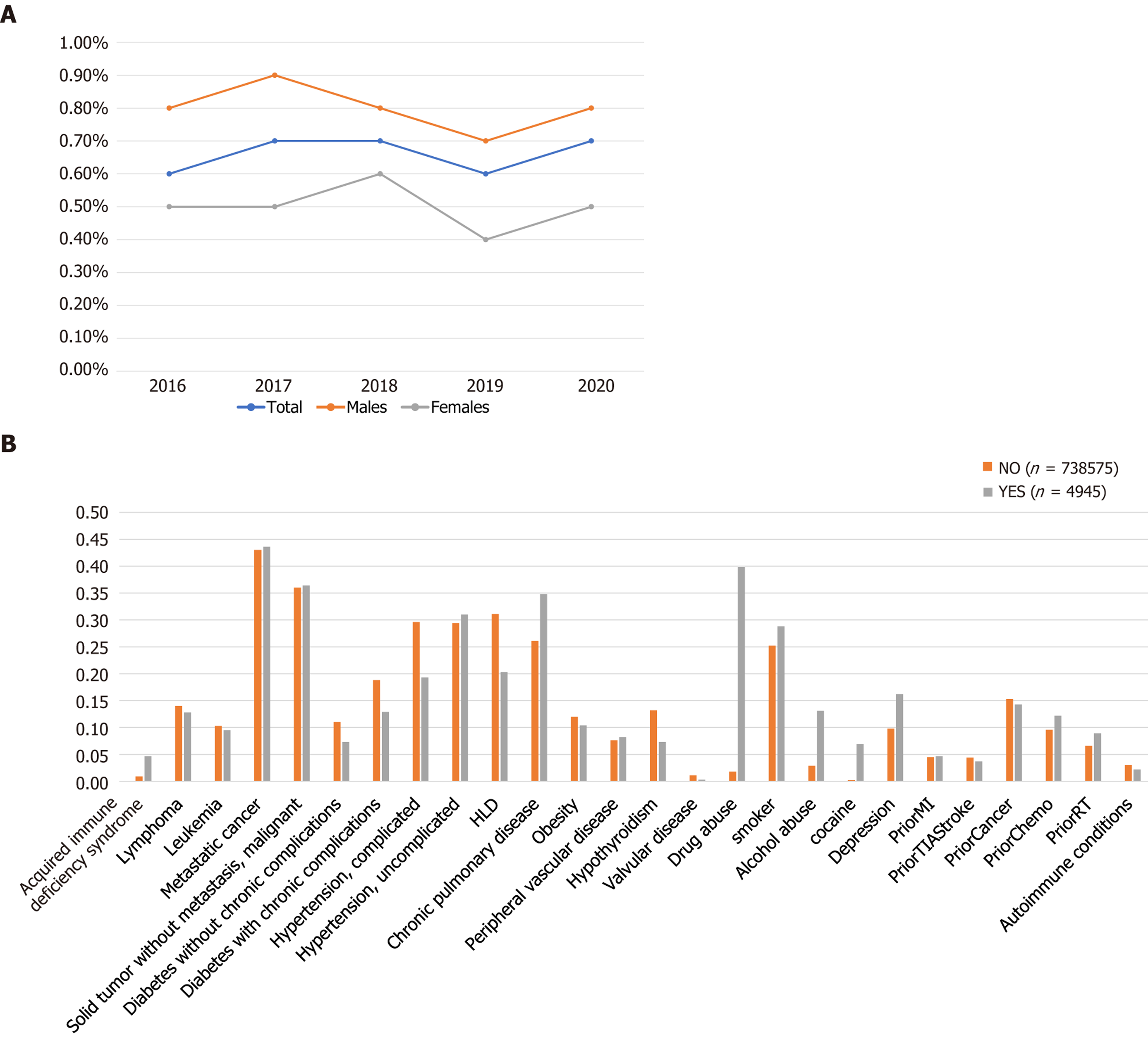

We identified a total of 743520 adult (≥ 18 years) cancer patients who were hospitalized with a primary discharge diagnosis of severe sepsis between 2016-2020. Out of these total hospitalizations, 4945 patients had a secondary diagnosis of CUD while 738575 patients served as control. The prevalence of severe sepsis with CUD was found to be 4.6%. Figure 2A depicts the trends in cannabis use among hospitalized cancer patients with severe sepsis. We compared the baseline demographics, hospital-specific characteristics, and comorbidities between the two cohorts (Table 1). Severe sepsis hospitalizations with CUD(+) cohort consisted of predominantly younger population (median age 58 years vs 69 years), males (67.9% vs 32.1%), blacks (23.7 vs 14.4%), low median income population (0-25th quartile 36.7% vs 27.2%), and Medicaid enrollees (35.2% vs 10.7%). Among hospitals in the west, there were more hospitalizations for severe sepsis among cancer patients with CUD than without (34.1% vs 24.2%) (Table 1, Figure 2B). We included patients with both hematological malignancies (leukemia and lymphoma) as well as non-hematological malignancies in our study. There was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of these malignancies in both cohorts (Supplementary Table 1).

| Baseline characteristics of cancer patients hospitalized with severe sepsis (n = 743520) | CUD(-) (n = 738575) | CUD(+) (n = 4945) | P value |

| Demographics | |||

| Age at admission, years (median with 25th-75th percentile values) | 69 (61-77) | 58 (49-64) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | - | - | < 0.001 |

| Males | 57.2 | 67.9 | - |

| Females | 42.8 | 32.1 | - |

| Race | - | - | < 0.001 |

| White | 70.8 | 64.8 | - |

| Black | 14.4 | 23.7 | - |

| Hispanic | 10 | 9.5 | - |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4.3 | 1.1 | - |

| Native American | 0.6 | 0.9 | - |

| Median household income1 | - | - | < 0.001 |

| 0th-25th | 27.2 | 36.7 | - |

| 26th-50th | 25 | 26.9 | - |

| 51th-75th | 24.6 | 21.5 | - |

| 76th-100th | 23.2 | 14.9 | - |

| Payer type | - | - | < 0.001 |

| Medicare | 66.1 | 38.2 | - |

| Medicaid | 10.7 | 35.2 | - |

| Private | 21.4 | 22.4 | - |

| Self-pay | 1.8 | 4.1 | - |

| No charge | 0.1 | 0.1 | - |

| Hospital-specific admitting characteristics | - | - | - |

| Hospital location and teaching status2 | - | - | < 0.001 |

| Rural | 6 | 5.6 | - |

| Urban non-teaching | 19.5 | 15.8 | - |

| Urban teaching | 74.5 | 78.7 | - |

| Hospital region | - | - | < 0.001 |

| Northeast | 17.9 | 10.8 | - |

| Midwest | 21 | 20.3 | - |

| South | 36.8 | 34.8 | - |

| West | 24.2 | 34.1 | - |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome | 0.9 | 4.7 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes without chronic complications | 11 | 7.3 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 18.8 | 12.9 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 29.6 | 19.3 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 29.4 | 31 | 0.012 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 31.1 | 20.3 | < 0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 26.1 | 34.8 | < 0.001 |

| Obesity | 12 | 10.4 | 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 7.6 | 8.2 | 0.11 |

| Hypothyroidism | 13.2 | 7.3 | < 0.001 |

| Valvular disease | 1.1 | 0.3 | < 0.001 |

| Tobacco use | 25.2 | 28.8 | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 2.9 | 13.1 | < 0.001 |

| Cocaine use | 0.2 | 6.9 | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 9.8 | 16.2 | < 0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 4.5 | 4.7 | 0.521 |

| Prior transient ischemic attack or stroke | 4.4 | 3.7 | 0.022 |

| Prior cancer | 15.3 | 14.3 | 0.038 |

| Prior chemotherapy | 9.6 | 12.2 | < 0.001 |

| Prior radiotherapy | 6.6 | 8.9 | < 0.001 |

| Autoimmune conditions | 3 | 2.2 | 0.003 |

Comorbidities including chronic pulmonary disease (34.8% vs 26.1%), depression (16.2 vs 9.8%), alcohol abuse (13.1% vs 2.9%), and tobacco use (28.8% vs 25.2%) were significantly more in the CUD(+) cohort than CUD(-) cohort. Diabetes mellitus with complications (18.8% vs 12.9%), hyperlipidemia (31.1% vs 20.3%), and obesity (12% vs 10.4%) were significantly higher in the CUD(-) cohort. Other comorbidities were not significantly different in both cohorts (Table 1 and Figure 2B).

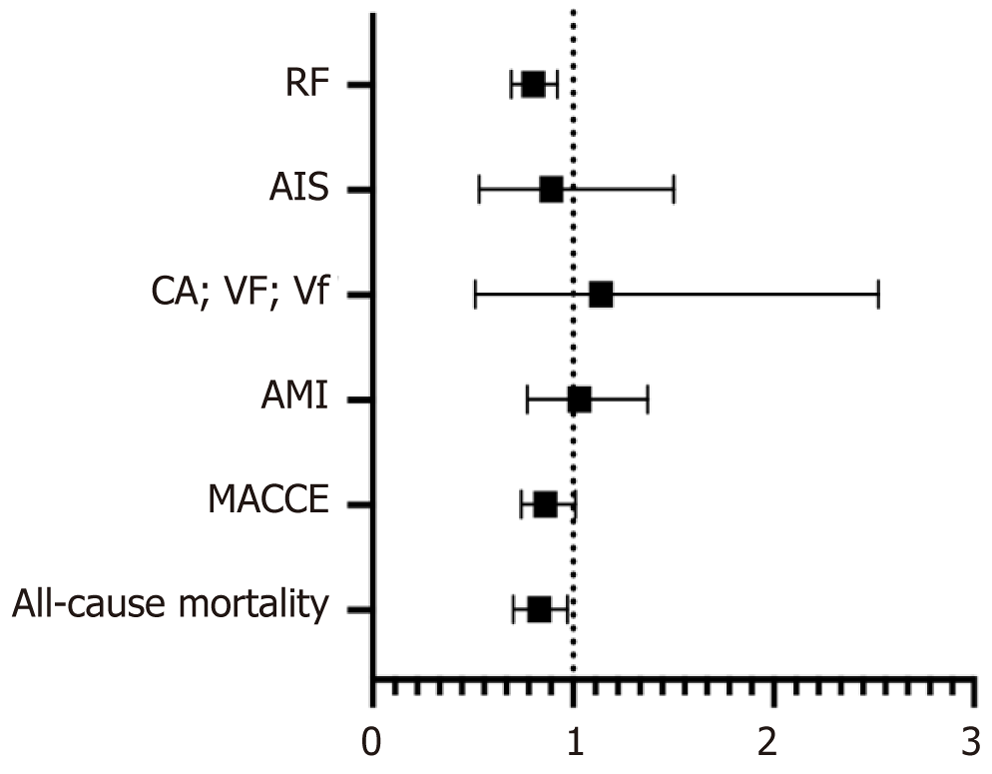

There was no significant difference in major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events in both cohorts (adjusted OR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.74-1.01, P = 0.059). There was no significant difference in the odds of acute myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, and acute ischemic stroke. However, the odds of respiratory failure were lower in the CUD(+) cohort (adjusted OR = 0.8, 95%CI: 0.69-0.92, P = 0.002) (Table 2).

| Outcomes | CUD(-) (n = 738575) | CUD(+) (n = 4945) | P value |

| MACCE | 36 | 28.4 | < 0.001 |

| All-cause in-hospital mortality | 30.5 | 23.4 | < 0.001 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 7.2 | 5.5 | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillationand ventricular flutter | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.038 |

| Acute ischemic stroke | 2 | 1.7 | 0.207 |

| Respiratory failure | 50.9 | 48.6 | 0.002 |

| Disposition of patient1 | - | - | < 0.001 |

| Routine | 18.8 | 31.5 | - |

| Transfer to short term facility | 3.4 | 3 | - |

| Other transfers (SNF, ICF etc.) | 25.8 | 17.8 | - |

| Home healthcare | 21 | 21.8 | - |

| Length of stay (median, days) | 7 | 7 | 0.034 |

| Total cost of hospitalization (median, USD) | 86615 | 94574 | < 0.001 |

All-cause mortality during hospitalization was found to be less in severe sepsis patients in the CUD(+) cohort compared to the CUD(-) cohort (2.9% vs 4.7%, P < 0.001). A multivariate regression analysis was performed to assess the inpatient all-cause mortality, which showed lower odds of mortality (adjusted OR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.7-0.9, P = 0.002) in severe sepsis patients with CUD compared to the CUD(-) cohort (Tables 2 and 3, Figure 3).

| Events | Adjusted OR | 95%CI | P value |

| MACCE | 0.86 | 0.74-1.01 | 0.059 |

| All-cause in-hospital mortality | 0.83 | 0.7-0.97 | 0.022 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.03 | 0.77-1.37 | 0.84 |

| Cardiac arrest, ventricular fibrillationand ventricular flutter | 1.14 | 0.51-2.52 | 0.754 |

| Acute ischemic stroke | 0.89 | 0.53-1.5 | 0.671 |

| Respiratory failure | 0.8 | 0.69-0.92 | 0.002 |

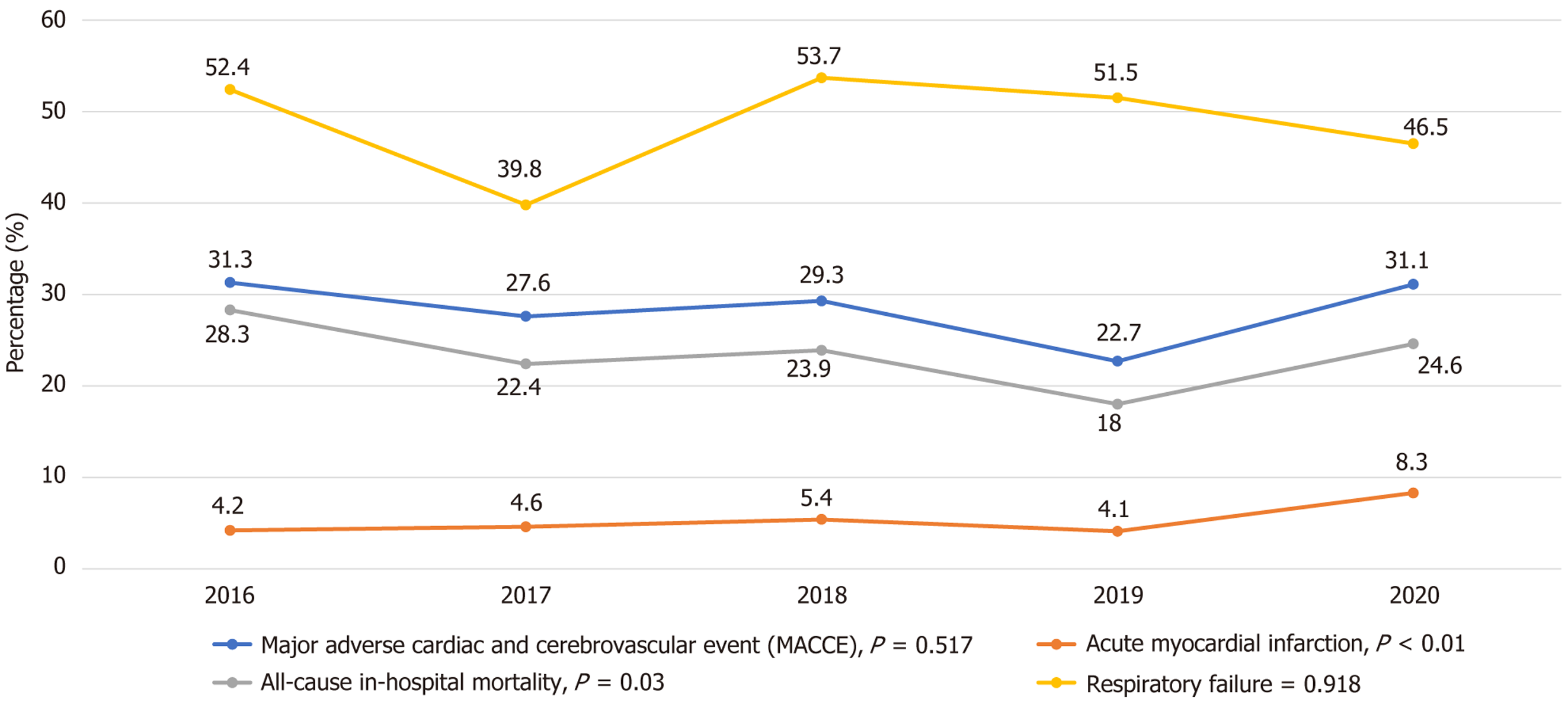

There was a significant linear upward trend in the incidence of acute MI in severe sepsis patients with CUD compared to the non-CUD cohort from 2016-2020 (P trend < 0.001). However, there was no significant linear trend in death during hospitalizations and respiratory failure in the CUD cohort from 2016 to 2020 (Figure 4).

Though the median length of hospitalization stay was similar in both cohorts (7 days), there was a statistical difference in the length of stay with a P value of 0.034, suggesting a difference in the distribution of the length of stay between the two cohorts. The cost of hospitalization was found to be significantly higher in the CUD cohort compared to the non-CUD cohort (median cost 94574 dollars vs 86615 dollars, P < 0.001) (Tables 2 and 3).

In our study of cancer patients admitted with severe sepsis, the CUD(+) cohort was more likely to be younger, male, black, and Medicaid enrollees. They had lower rates of cardiovascular comorbidities but higher rates of chronic pulmonary disease, substance use, and depression. They had lower odds of all-cause mortality and respiratory failure, but higher median cost of hospital stay compared to the CUD(-) cohort. In line with our findings, several authors have also previously examined the higher rates of cannabis use and dependence among young adults and blacks[4,23-25]. Furthermore, we report higher rates of CUD in hospitals based in the western United States. This is reflective of data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, where the Western states of Washington, Oregon, Nevada, and California reported the highest rates of marijuana use[26].

Our study revealed higher rates of comorbid alcohol use (13.1% vs 2.9%) and mood disorders (16.2% vs 9.8%) amongst the CUD(+) arm. Though concurrent alcohol and CUD are understudied, some authors have noted a significant two-way association between major depressive disorder and concurrent alcohol and cannabis use[27]. One primary care-based electronic health record study reported significantly higher odds for other substance use and most mental health conditions, including social anxiety, bipolar disorder, and depression, among those with CUD or cannabis use[28]. We, too, find that patients with CUD were more likely to have higher rates of concomitant depression. Animal studies have explored the neuromodulatory effects of cannabis on gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate neurotransmission, though this is still of unclear clinical significance[29,30].

A nationally representative 2018 survey of medical oncologists reported that nearly half (46%) recommend medical marijuana to their patients[31]. From a patient perspective, active users most often cited cannabis use for physical and neuropsychiatric symptoms, including pain, poor sleep or appetite, nausea, low mood and stress[32]. Interestingly, one study of cancer patients undergoing treatment noted that those using cannabis also tended to report more severe symptoms, though whether this is linked to cannabis use is unclear due to the cross-sectional design[25]. A multivariable analysis of different cancers found a statistically significant association between patients with gastrointestinal cancers and cannabis use[33]. A minority of patients discuss cannabis use with their healthcare providers or have medical authorization for its usage, with rates of around 25% and 30% respectively[33,34].

A cross-sectional study of 905 participants in Australia found comparable rates of CUD (32%) among those who used cannabis medically vs those who reported illicit use, with withdrawal and tolerance symptoms being the most common manifestations[35]. Another study found that around 80% of medical users also report recreational use and are more prone to daily usage, highlighting the overlap between medical and recreational cannabis use[36]. The significance of these study findings are underscored by data that suggest important gaps in medical literacy among regular cannabis users on its health effects, with a tendency to underestimate risks and overestimate benefits[37]. In fact, evidence-based studies regarding the potential risks and benefits of medical cannabis have been heterogeneous and inconsistent[38-40]. In part, this is due to its federal status as a Class I narcotic, limiting research funding[41].

Cannabinoids (CBs), the most well-researched chemical compound of cannabis, exert their action in the human body via the endocannabinoid system and are classified pharmacologically into the intoxicating tetrahydrocannabinol, non-intoxicating cannabidiol (CBD) and several other minor, less well-studied CBs[42]. Experiments investigating the cardiovascular effects of CBD in various pathological states have exhibited a wide range of effects. For example, reductions in stress related hypertension, not causing hypotension in animal hypertension models as well as vascular and cardiac protection in models of diabetes, sepsis and MI[43]. There is also a fair amount of basic science data supporting the ability of CBs to attenuate inflammatory pathways and oxidative stress by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines in sepsis[44-47]. Though much of this research has focused on CBD and tetrahydrocannabinol, more recent studies have also demonstrated similar anti-inflammatory properties during the lipopolysaccharide-induced, macrophage-mediated, cytokine storm of sepsis among minor cannabinoid groups like tetrahydrocannabivarin, cannabichromene, and cannabinol[48]. Some authors have also cited its anticancer potential through a diverse range of me

The link between inflammation, sepsis, and its subsequent adverse consequences like shock, metabolic acidosis and end-organ dysfunction is through the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, during which there is a hypermetabolic accumulation of hydrogen peroxide[47,57]. Hence, reducing maladaptive inflammation could be an important component of future therapeutic options aiming to improve outcomes in sepsis[43,58,59]. For example, a mouse sepsis experiment demonstrated decreased systemic inflammation, as well as cardiac and renal protective effects in mice injected with CBD compared to controls[60]. There have been other observational data with concurrent findings of paradoxically improved outcomes among cannabis users. One NIS study between 2005 and 2014 found that among 6073862 COPD admissions, those with cannabis use (0.4%) had statistically significantly lower odds of in-hospital mortality and pneumonia compared to those without cannabis use (99.6%). The cannabis use cohort also had lower odds of sepsis and respiratory failure, but this did not reach statistical significance[61]. In another cross-sectional analysis of the NIS database between 2007-2011, multivariable logistic regression showed lower in-hospital mortality among cancer patients with active marijuana use vs non-users (OR = 0.44, 95%CI: 0.35-0.55)[62]. In a retrospective cohort study of 510007 vascular surgery patients, those with CUD had a lower incidence of sepsis in the perioperative period (OR = 0.64, 95%CI: 0.47-0.85), though this association was not statistically significant on sensitivity analysis[63]. In contrast, there have also been studies showing cannabis use to be associated with higher risk for some adverse outcomes. For example, a mendelian randomization study of patients with genetic liability for cannabis use identified a greater risk for small vessel strokes and atrial fibrillation on multivariate analysis[64]. Another population-level cohort study comparing individuals reporting cannabis use within one year to propensity-matched controls found that the cannabis use group had significantly higher rates of emergency room visits and hospital admissions, though there was no difference in all-cause mortality (OR = 0.99, 95%CI: 0.49-2.02)[65].

The major strength of our study is that it utilizes the largest inpatient dataset, which encompasses hospitalizations across 47 states participating in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, approximating around 97% of the United States population, or around 7 million unweighted and 35 million weighted admissions nationwide. This allows for an analysis of trends and outcomes across various sociodemographic factors and co-morbidities. As a result, clinicians can better understand nationwide patterns, associations and disease burden. However, our study also has some limitations. The major limitation is that, as a population level administrative dataset, the NIS collects data from admission related International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes and not individual patients. Additionally, through the retrospective cohort design, there is a possibility of unmeasured confounding factors, selection, and sampling bias. Hence, no causality can be inferred regarding outcomes of CUD in sepsis among cancer patients. Furthermore, data regarding prior vs current cancer, chemotherapy regimen, age related variations in cancer profile, laboratory and microbiological data and the source of sepsis could not be assessed, which may have influenced the findings in our study by introducing uncontrolled confounders. Despite these limitations, we provide contemporary results from the largest database for outcomes of severe sepsis in cancer patients with CUD.

Prospective cohort studies with standardized data collection on cancer staging, treatment history, and microbiological data can help better account for these variables and improve the robustness of the study findings. Additionally, further research is needed to continue to elucidate the underlying immunological mechanisms of how cannabis use may influence the prognosis of critically ill patients. Furthermore, our study emphasizes the need for heightened awareness of CUD among cancer patients and its potential effects on sepsis outcomes. Healthcare providers need education on this relationship to deliver informed care. Importantly, policies should promote access to treatment for CUD treatment and support integrated care models for this vulnerable population.

Our study is unique in investigating the implications of CUD on severe sepsis outcomes in the cancer population. We found among cancer patients with severe sepsis, those with CUD tended to be younger, black, male, Medicaid enrollees and had higher rates of substance use disorder, depression, chronic pulmonary disease and healthcare utilization cost. However, they had lower rates of cardiovascular co-morbidities and paradoxically lower odds of all-cause mortality and respiratory failure on multivariable regression analysis. A possible link in unraveling this paradox is the potential for CBs to modulate the systemic inflammatory response syndrome of sepsis.

With the increasing prevalence of cannabis use, we aim to inform clinicians about the importance of understanding how CUD affects sepsis in cancer patients. Focusing on the presence of CUD among these patients can enhance care and management. Furthermore, future studies with prospective designs would allow for better control of confounders and more robust conclusions. Additionally, research should also aim to clarify the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of CUD in sepsis and investigate potential therapeutic options. In the interim, we express concern over findings in the present literature which suggest significantly overlapping recreational and medicinal usage of cannabis and low disclosure rates of such use in the physician-patient relationship, consequently limiting informed decision making and predisposing cancer patients towards CUD without clear medical benefit.

| 1. | Sen MS, Sarkar S, Singh YC. The DSM: 5 Criteria of cannabis use disorder: Methods and applications. In: Martin CR, Patel VB, Preedy VR, editor. Cannabis Use, Neurobiology, Psychology, and Treatment. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2023: 499-510. |

| 2. | Leung J, Chan GCK, Hides L, Hall WD. What is the prevalence and risk of cannabis use disorders among people who use cannabis? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Behav. 2020;109:106479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hasin DS, Wall MM, Choi CJ, Alschuler DM, Malte C, Olfson M, Keyes KM, Gradus JL, Cerdá M, Maynard CC, Keyhani S, Martins SS, Fink DS, Livne O, Mannes Z, Sherman S, Saxon AJ. State Cannabis Legalization and Cannabis Use Disorder in the US Veterans Health Administration, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80:380-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cousins MM, Jannausch ML, Coughlin LN, Jagsi R, Ilgen MA. Prevalence of cannabis use among individuals with a history of cancer in the United States. Cancer. 2021;127:3437-3444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Legare CA, Raup-Konsavage WM, Vrana KE. Therapeutic Potential of Cannabis, Cannabidiol, and Cannabinoid-Based Pharmaceuticals. Pharmacology. 2022;107:131-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bar-Lev Schleider L, Mechoulam R, Lederman V, Hilou M, Lencovsky O, Betzalel O, Shbiro L, Novack V. Prospective analysis of safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in large unselected population of patients with cancer. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;49:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13300] [Cited by in RCA: 15468] [Article Influence: 2578.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Dariš B, Tancer Verboten M, Knez Ž, Ferk P. Cannabinoids in cancer treatment: Therapeutic potential and legislation. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2019;19:14-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Clark TM. Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis Suggests that Cannabis Use May Reduce Cancer Risk in the United States. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2021;6:413-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15803] [Cited by in RCA: 17142] [Article Influence: 1904.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Cecconi M, Evans L, Levy M, Rhodes A. Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet. 2018;392:75-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 810] [Cited by in RCA: 1394] [Article Influence: 199.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, Mcintyre L, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Schorr C, Simpson S, Wiersinga WJ, Alshamsi F, Angus DC, Arabi Y, Azevedo L, Beale R, Beilman G, Belley-Cote E, Burry L, Cecconi M, Centofanti J, Coz Yataco A, De Waele J, Dellinger RP, Doi K, Du B, Estenssoro E, Ferrer R, Gomersall C, Hodgson C, Hylander Møller M, Iwashyna T, Jacob S, Kleinpell R, Klompas M, Koh Y, Kumar A, Kwizera A, Lobo S, Masur H, McGloughlin S, Mehta S, Mehta Y, Mer M, Nunnally M, Oczkowski S, Osborn T, Papathanassoglou E, Perner A, Puskarich M, Roberts J, Schweickert W, Seckel M, Sevransky J, Sprung CL, Welte T, Zimmerman J, Levy M. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e1063-e1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 1344] [Article Influence: 336.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Williams MD, Braun LA, Cooper LM, Johnston J, Weiss RV, Qualy RL, Linde-Zwirble W. Hospitalized cancer patients with severe sepsis: analysis of incidence, mortality, and associated costs of care. Crit Care. 2004;8:R291-R298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sharma A, Nguyen P, Taha M, Soubani AO. Sepsis Hospitalizations With Versus Without Cancer: Epidemiology, Outcomes, and Trends in Nationwide Analysis From 2008 to 2017. Am J Clin Oncol. 2021;44:505-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gudiol C, Albasanz-Puig A, Cuervo G, Carratalà J. Understanding and Managing Sepsis in Patients With Cancer in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:636547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang YG, Zhou JC, Wu KS. High 28-day mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis and concomitant active cancer. J Int Med Res. 2018;46:5030-5039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hensley MK, Donnelly JP, Carlton EF, Prescott HC. Epidemiology and Outcomes of Cancer-Related Versus Non-Cancer-Related Sepsis Hospitalizations. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1310-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ou SM, Chu H, Chao PW, Lee YJ, Kuo SC, Chen TJ, Tseng CM, Shih CJ, Chen YT. Long-Term Mortality and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Sepsis Survivors. A Nationwide Population-based Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:209-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cooper AJ, Keller SP, Chan C, Glotzbecker BE, Klompas M, Baron RM, Rhee C. Improvements in Sepsis-associated Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with Cancer versus Those without Cancer. A 12-Year Analysis Using Clinical Data. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17:466-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. NIS Overview. [cited 28 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. |

| 21. | United States Centers For Disease Control And Prevention. ICD-10-CM. Jun 7, 2024. [cited 28 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd-10-cm.htm. |

| 22. | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR)For ICD-10-CM Diagnoses. [cited 28 August 2024]. Available from: https:www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/dxccsr.jsp. |

| 23. | Kwon E, Oshri A, Zapolski TCB, Zuercher H, Kogan SM. Substance use trajectories among emerging adult Black men: Risk factors and consequences. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2023;42:1816-1824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ahuja M, Haeny AM, Sartor CE, Bucholz KK. Perceived racial and social class discrimination and cannabis involvement among Black youth and young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;232:109304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Azizoddin DR, Cohn AM, Ulahannan SV, Henson CE, Alexander AC, Moore KN, Holman LL, Boozary LK, Sifat MS, Kendzor DE. Cannabis use among adults undergoing cancer treatment. Cancer. 2023;129:3498-3508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Interactive NSDUH State Estimates. [cited 28 August 2024]. Database: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Internet]. Available from: https://datatools.samhsa.gov/saes/state. |

| 27. | Pacek LR, Martins SS, Crum RM. The bidirectional relationships between alcohol, cannabis, co-occurring alcohol and cannabis use disorders with major depressive disorder: results from a national sample. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:188-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Padwa H, Huang D, Mooney L, Grella CE, Urada D, Bell DS, Bass B, Boustead AE. Medical conditions of primary care patients with documented cannabis use and cannabis use disorder in electronic health records: a case control study from an academic health system in a medical marijuana state. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2022;17:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Martin M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Maldonado R, Valverde O. Involvement of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in emotional behaviour. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2002;159:379-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | De Giacomo V, Ruehle S, Lutz B, Häring M, Remmers F. Differential glutamatergic and GABAergic contributions to the tetrad effects of Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol revealed by cell-type-specific reconstitution of the CB1 receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2020;179:108287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Braun IM, Wright A, Peteet J, Meyer FL, Yuppa DP, Bolcic-Jankovic D, LeBlanc J, Chang Y, Yu L, Nayak MM, Tulsky JA, Suzuki J, Nabati L, Campbell EG. Medical Oncologists' Beliefs, Practices, and Knowledge Regarding Marijuana Used Therapeutically: A Nationally Representative Survey Study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1957-1962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pergam SA, Woodfield MC, Lee CM, Cheng GS, Baker KK, Marquis SR, Fann JR. Cannabis use among patients at a comprehensive cancer center in a state with legalized medicinal and recreational use. Cancer. 2017;123:4488-4497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Salz T, Meza AM, Chino F, Mao JJ, Raghunathan NJ, Jinna S, Brens J, Furberg H, Korenstein D. Cannabis use among recently treated cancer patients: perceptions and experiences. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31:545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hawley P, Gobbo M. Cannabis use in cancer: a survey of the current state at BC Cancer before recreational legalization in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2019;26:e425-e432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mills L, Lintzeris N, O'Malley M, Arnold JC, McGregor IS. Prevalence and correlates of cannabis use disorder among Australians using cannabis products to treat a medical condition. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022;41:1095-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Turna J, Balodis I, Munn C, Van Ameringen M, Busse J, MacKillop J. Overlapping patterns of recreational and medical cannabis use in a large community sample of cannabis users. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;102:152188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kruger DJ, Kruger JS, Collins RL. Cannabis Enthusiasts' Knowledge of Medical Treatment Effectiveness and Increased Risks From Cannabis Use. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34:436-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Wilkie G, Sakr B, Rizack T. Medical Marijuana Use in Oncology: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:670-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Machado Rocha FC, Stéfano SC, De Cássia Haiek R, Rosa Oliveira LM, Da Silveira DX. Therapeutic use of Cannabis sativa on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting among cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2008;17:431-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cannabis-In-Cachexia-Study-Group; Strasser F, Luftner D, Possinger K, Ernst G, Ruhstaller T, Meissner W, Ko YD, Schnelle M, Reif M, Cerny T. Comparison of orally administered cannabis extract and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in treating patients with cancer-related anorexia-cachexia syndrome: a multicenter, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial from the Cannabis-In-Cachexia-Study-Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3394-3400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Braun IM, Abrams DI, Blansky SE, Pergam SA. Cannabis and the Cancer Patient. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2021;2021:68-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Lal S, Shekher A, Puneet, Narula AS, Abrahamse H, Gupta SC. Cannabis and its constituents for cancer: History, biogenesis, chemistry and pharmacological activities. Pharmacol Res. 2021;163:105302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kicman A, Toczek M. The Effects of Cannabidiol, a Non-Intoxicating Compound of Cannabis, on the Cardiovascular System in Health and Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Jean-Gilles L, Gran B, Constantinescu CS. Interaction between cytokines, cannabinoids and the nervous system. Immunobiology. 2010;215:606-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Pellati F, Borgonetti V, Brighenti V, Biagi M, Benvenuti S, Corsi L. Cannabis sativa L. and Nonpsychoactive Cannabinoids: Their Chemistry and Role against Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1691428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Martini S, Gemma A, Ferrari M, Cosentino M, Marino F. Effects of Cannabidiol on Innate Immunity: Experimental Evidence and Clinical Relevance. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Dinu AR, Rogobete AF, Bratu T, Popovici SE, Bedreag OH, Papurica M, Bratu LM, Sandesc D. Cannabis Sativa Revisited-Crosstalk between microRNA Expression, Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Endocannabinoid Response System in Critically Ill Patients with Sepsis. Cells. 2020;9:307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Gojani EG, Wang B, Li DP, Kovalchuk O, Kovalchuk I. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Minor Cannabinoids CBC, THCV, and CBN in Human Macrophages. Molecules. 2023;28:6487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Davis MP. Cannabinoids for Symptom Management and Cancer Therapy: The Evidence. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:915-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Fu Z, Zhao PY, Yang XP, Li H, Hu SD, Xu YX, Du XH. Cannabidiol regulates apoptosis and autophagy in inflammation and cancer: A review. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1094020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Baumeister SE, Baurecht H, Nolde M, Alayash Z, Gläser S, Johansson M, Amos CI; International Lung Cancer Consortium, Johnson EC, Hung RJ. Cannabis Use, Pulmonary Function, and Lung Cancer Susceptibility: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:1127-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Tomko AM, Whynot EG, O'Leary LF, Dupré DJ. Anti-cancer potential of cannabis terpenes in a Taxol-resistant model of breast cancer. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2022;100:806-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Buchtova T, Lukac D, Skrott Z, Chroma K, Bartek J, Mistrik M. Drug-Drug Interactions of Cannabidiol with Standard-of-Care Chemotherapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:2885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Twelves C, Sabel M, Checketts D, Miller S, Tayo B, Jove M, Brazil L, Short SC; GWCA1208 study group. A phase 1b randomised, placebo-controlled trial of nabiximols cannabinoid oromucosal spray with temozolomide in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:1379-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Braun IM, Bohlke K, Abrams DI, Anderson H, Balneaves LG, Bar-Sela G, Bowles DW, Chai PR, Damani A, Gupta A, Hallmeyer S, Subbiah IM, Twelves C, Wallace MS, Roeland EJ. Cannabis and Cannabinoids in Adults With Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:1575-1593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Abu-Amna M, Salti T, Khoury M, Cohen I, Bar-Sela G. Medical Cannabis in Oncology: a Valuable Unappreciated Remedy or an Undesirable Risk? Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2021;22:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Pravda J. Metabolic theory of septic shock. World J Crit Care Med. 2014;3:45-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Meza A, Lehmann C. Betacaryophyllene - A phytocannabinoid as potential therapeutic modality for human sepsis? Med Hypotheses. 2018;110:68-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Joffre J, Yeh CC, Wong E, Thete M, Xu F, Zlatanova I, Lloyd E, Kobzik L, Legrand M, Hellman J. Activation of CB(1)R Promotes Lipopolysaccharide-Induced IL-10 Secretion by Monocytic Myeloid-Derived Suppressive Cells and Reduces Acute Inflammation and Organ Injury. J Immunol. 2020;204:3339-3350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Maayah ZH, Ferdaoussi M, Alam A, Takahara S, Silver H, Soni S, Martens MD, Eurich DT, Dyck JRB. Cannabidiol Suppresses Cytokine Storm and Protects Against Cardiac and Renal Injury Associated with Sepsis. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2024;9:160-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Gunasekaran K, Voruganti DC, Singh Rahi M, Elango K, Ramalingam S, Geeti A, Kwon J. Trends in Prevalence and Outcomes of Cannabis Use Among Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Hospitalizations: A Nationwide Population-Based Study 2005-2014. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2021;6:340-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Vin-Raviv N, Akinyemiju T, Meng Q, Sakhuja S, Hayward R. Marijuana use and inpatient outcomes among hospitalized patients: analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample database. Cancer Med. 2017;6:320-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | McGuinness B, Goel A, Elias F, Rapanos T, Mittleman MA, Ladha KS. Cannabis use disorder and perioperative outcomes in vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73:1376-1387.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Zhao J, Chen H, Zhuo C, Xia S. Cannabis Use and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:676850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Vozoris NT, Zhu J, Ryan CM, Chow CW, To T. Cannabis use and risks of respiratory and all-cause morbidity and mortality: a population-based, data-linkage, cohort study. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2022;9:e001216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |