Published online Mar 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i1.98487

Revised: October 30, 2024

Accepted: November 19, 2024

Published online: March 9, 2025

Processing time: 167 Days and 4.2 Hours

The care of a patient involved in major trauma with exsanguinating haemorrhage is time-critical to achieve definitive haemorrhage control, and it requires co-ordinated multidisciplinary care. During initial resuscitation of a patient in the emergency department (ED), Code Crimson activation facilitates rapid decision-making by multi-disciplinary specialists for definitive haemorrhage control in operating theatre (OT) and/or interventional radiology (IR) suite. Once this decision has been made, there may still be various factors that lead to delay in transporting the patient from ED to OT/IR. Red Blanket protocol identifies and addresses these factors and processes which cause delay, and aims to facilitate rapid and safe transport of the haemodynamically unstable patient from ED to OT, while minimizing delay in resuscitation during the transfer. The two pro

Core Tip: Code Crimson is aimed at rapid decision-making for definitive haemorrhage control, while Red Blanket addresses the factors and processes causing delay and aims to get the patient rapidly to operating theatre/ interventional radiology for definitive haemorrhage control. Both these processes complement each other. Hence, unifying these processes into a single workflow would ensure combined benefits of both these protocols, aimed at reducing the time from emergency department to definitive haemorrhage control in a patient with exsanguinating trauma. This will eventually aim to improve the care for the complex trauma patients requiring multi-disciplinary care and definitive haemorrhage control.

- Citation: Pothiawala S, Bhagvan S, MacCormick A. Incorporating red blanket protocol within code crimson: Streamlining definitive trauma care amid the chaos. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(1): 98487

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i1/98487.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i1.98487

The care of a patient involved in major trauma is time-critical and requires co-ordinated multidisciplinary care. Trauma care has evolved over time with a range of interventions like trauma team activation criteria, composition of trauma team members, recommended equipment list and trauma care protocols[1]. Haemorrhagic shock from exsanguinating bleeding is a major cause of mortality in trauma patients, and these patients constitute a small subset of the total trauma patients. To address this challenge, rapid initiation of damage control resuscitation in the emergency department (ED) combined with definitive haemorrhage control, either through damage control surgery or angio-embolization by interventional radiology (IR) is important for optimal patient care[2].

These patients will benefit from a step-up response in addition to the standard trauma team activation in the ED. To address this, Code Crimson protocol has been implemented across hospitals in Australasia[3,4], with a focus on early initiation of massive transfusion protocol (MTP) and definitive intervention to control haemorrhage[5]. In Singapore, Woodlands Health and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH) have implemented Critical Haemorrhage to Operating-room Protocol (CHOP), which is the equivalent of Code Crimson protocol in Australasia and United States. A study of 148 patients who met the Code Crimson activation criteria at Auckland City Hospital from August 2015 to February 2021 showed significant reduction in the average time from arrival in ED to transfer to operating theatre (OT) or IR for definitive intervention to a mean of 54 minutes, and a mortality rate of of 19.6%[5]. Another study of 37 patients who were managed by CHOP protocol activation in KTPH, Singapore from March 2018 to December 2019 showed that there was significant improvement in time to definitive intervention in OT/IR (78 min vs 113 min), as well as mortality (11% vs 31%)[6].

Activating Code Crimson mobilizes additional multi-disciplinary specialists (trauma surgeon, interventional radiologist, intensive care specialist, anaesthetist, blood bank) to be present in the ED during the initial resuscitation of the patient. This helps in rapid decision-making for definitive haemorrhage control in the OT or IR suite[5,7].

Code Crimson should be activated in the ED, either upon pre-hospital notification or upon patient’s arrival in the ED, if a trauma patient meets any two out of the following four criteria[5]: (1) Heart rate > 120 beats per minute; (2) Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg; (3) Penetrating injuries to head, neck, chest, abdomen, proximal extremities (or) blunt trauma leading to pelvic disruption, massive hemothorax, uncontrolled maxillo-facial haemorrhage or limb amputation; and (4) Positive Focused Abdominal Sonography in Trauma.

Once the decision for definitive haemorrhage control has been made by the Trauma and IR specialists, there are factors that can still lead to delays in transporting the patient from ED to OT/IR. Some of these factors include various pre-operative procedures like coordination amongst various stakeholders regarding OT location and timing of surgery, anaesthetist availability, consent-taking, ensuring patient property lists, pre-operative checklists, awaiting results of laboratory or radiological investigations, mobilizing appropriate staff for transfer, etc.[8,9]. Moreover, it also involves the ED/Trauma registrar and ED nurses making multiple phone calls to book the emergency OT and arranging patient transfer. Moreover, a study suggested higher mortality rate and increased intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS) for major trauma patients with exsanguinating haemorrhage who faced delayed transportation from ED to OT for definitive haemorrhage control[10,11].

The Red Blanket protocol was initially implemented at the Los Angeles County Trauma Center and then at Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital to avoid these delays once the decision has been made[11-13]. Red Blanket is a communication process intended to facilitate rapid and safe transport of a haemodynamically unstable patients from ED to OT/IR, with an attempt to address the various factors that lead to delay once the decision has been made. It also aims to ensure minimal delay in resuscitation during the transfer. Implementation of Red Blanket protocol at The Royal Brisbane and Woman’s Hospital led to significant reduction in time from ED to OT from 153 minutes to 27 minutes post-protocol implementation[13]. A recent study from New Zealand also showed reduction in ED to definitive surgery time from 79 minutes pre-red blanket protocol implementation to 67 minutes post-implementation. This study also showed a trend towards reduced LOS in ICU and improved clinical outcomes in this group of patients[8]. These studies show that implementation of Red Blanket protocol leads to reduction in time for transferring the patient from ED to OT/IR once a decision has been made for definitive haemorrhage control for patients with exsanguinating haemorrhage.

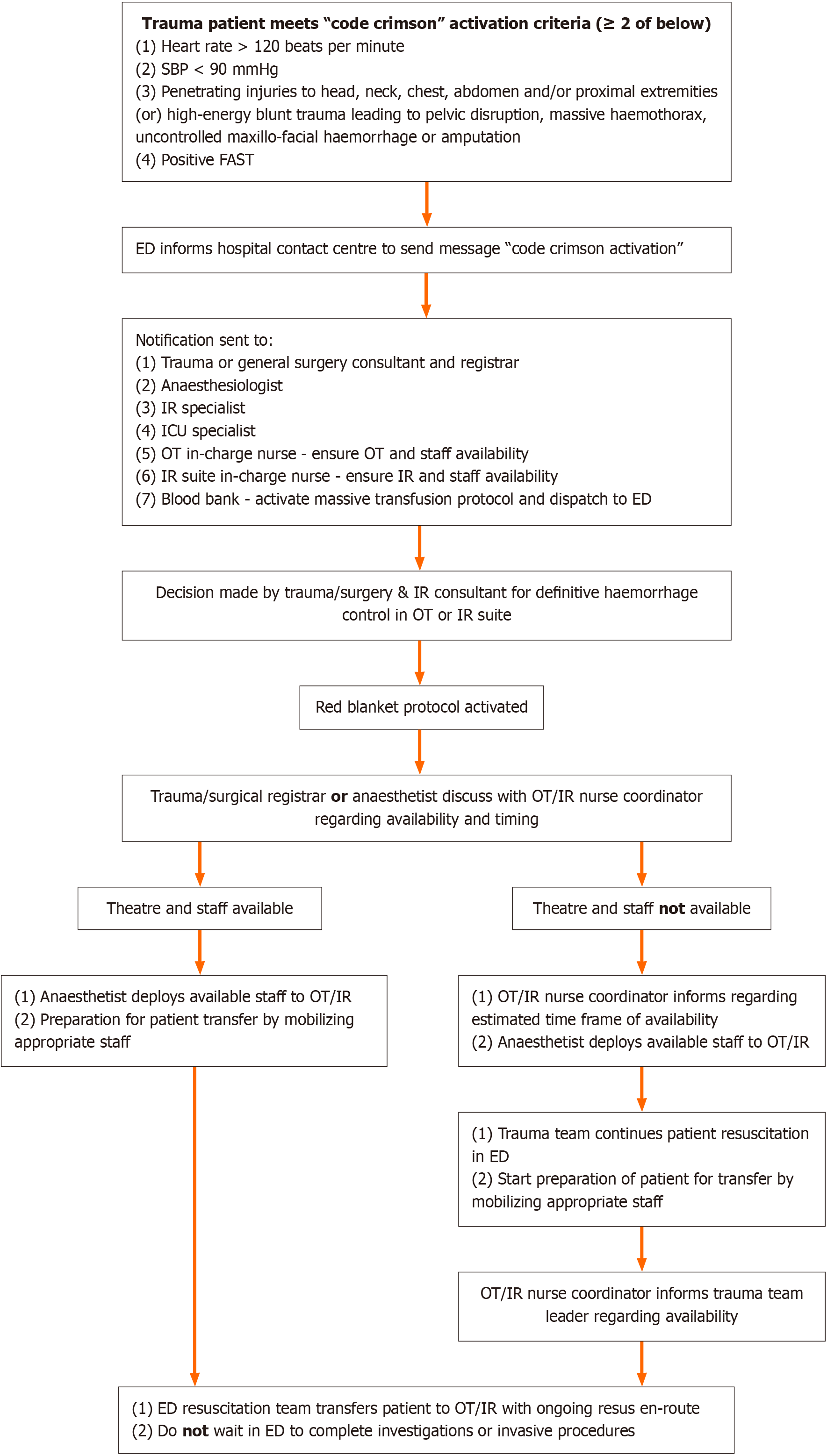

While most trauma systems activate trauma teams to respond to patients with major trauma, many hospitals do not have a workflow for rapid decision making and definitive haemorrhage control for the subset of patients with massive or exsanguinating haemorrhage. Implementing a combination of Code Crimson and Red Blanket protocols will be effective in ensuring early definitive haemorrhage control, as well as address the issues which often lead to a delay in transferring the patient to OT/IR. The proposed unified workflow for activation of Code Crimson and Red Blanket protocols is outlined in Figure 1. Once activated, communication between various multi-disciplinary coordinators occurs rapidly and seamlessly, with as few calls as necessary. The trauma team registrar or the anaestheist immediately contact the OT or IR nurse coordinator regarding theatre availability. If the theatre is immediately available, the ED resuscitation team accompanies the patient to OT/IR with ongoing resuscitation en-route. The trauma team does not need to not wait to complete unnecessary investigations, radiographic imaging or invasive procedures like arterial line or central venous line insertion prior to transfer to OT. Thus, the Red Blanket protocol activation minimizes the number of calls that otherwise need to be made by the ED team as well as the trauma team to various stakeholders, and it relieves the ED resuscitation team from these administrative tasks to focus on patient resuscitation. If OT/IR suite is not immediately available, resuscitation is continued in ED and the resus team transfers the patient once they are informed by the OT/IR nurse coordinator regarding the availability. Post-operatively, the patient will be immediately transferred to ICU as required for continued management. Thus, streamlining this transfer process minimizes multiple calls, reduces delay, and provides a safe process for appropriate staff required during the transfer.

Implementation of this protocol not only focuses on time-related benefits to improve patient outcomes, but will also foster improved team communication across various stakeholders by establishing clear role and guidelines. Furthermore, with a structured framework in place, resources can be allocated more effectively, ensuring that critical supplies and personnel are rapidly available when needed. This in-turn will encourage collaborative decision-making and a cohesive, coordinated approach while managing critical patients.

Implementation of a new protocol in a hospital can face several challenges and barriers. Resistance to change is a significant hurdle, as staff are already accustomed to existing protocols and hence may be hesitant to adopt new workflows. To overcome this, training and education are crucial, but that requires time and resources that can impact work schedules and budget. Logistical issues of integrating the new unified workflow in the existing system, along with adherence to the new protocol amidst the high-pressure situation also poses a challenge.

Hence, to overcome these challenges, investing in training of this new unified protocol will facilitate smoother transition to the new workflow. This necessitates comprehensive education and multi-disciplinary simulation exercises to ensure that all the team members across various departments are proficient in their respective roles. Education regarding this workflow will provide the foundational knowledge regarding the principles and objectives of the combined workflow, while simulation will allow the physicians and nurses to practice and refine their skills during the scenarios. This dual approach will help foster collaboration, enhance communication as well as prepare the staff the respond effectively under pressure, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Table 1 compares the key features, benefits and limitations of Code Crimson, Red Blanket and Unified Protocol respectively. To ensure adherence to the new protocol, all cases where the unified Code Crimson/Red Blanket protocol was activated should be subsequently evaluated, and the review should include the appropriateness of patient inclusion and whether other pre-determined Key Performance Indicators were met. The outcomes can be measured by comparing the following determinants between the pre-protocol and post-protocol implementation groups: Time from the patient’s arrival in the ED to transfer to the operating room for definite haemorrhage control, the number of blood products used upon activation of MTP, overall hospital LOS) as well as 30- and 90-day survival.

| Protocol | Key features | Benefits | Limitations |

| Code crimson | (1) Second-tier of response in addition to the standard trauma team activation for trauma patients with exsanguinating haemorrhage; and (2) Effective step-up strategy to reduce morbidity and mortality in major trauma patients with severe haemorrhage | (1) Mobilization of additional personnel and resources specifically required for decision-making; (2) Expedites time for rapid diagnosis of major haemorrhage; (3) Initiation of haemostatic resuscitation using MTP; and (4) Rapid operative or radiological intervention for definitive haemorrhage control | (1) Does not address the factors leading to delays in transporting patient from ED to OT/IR after decision for haemorrhage control; and (2) Multiple phone calls amongst various stakeholders regarding OT location and timing of surgery, anaesthetist availability, consent-taking, pre-operative checklists, mobilizing staff for transfer |

| Red blanket | (1) Address the various factors that lead to delay once the decision has been made to transfer patient from ED to OT/IR; and (2) A communication process intended to facilitate rapid and safe transport of a haemodynamically unstable patients | (1) Significant reduction in time for transferring the patient from ED to OT/IR once a decision has been made for definitive haemorrhage control; (2) Ensure minimal delay in resuscitation during the transfer; and (3) Reduced length of stay in ICU and improved clinical outcomes | (1) Relies on assumption that hospital has an existing Code Crimson workflow; and (2) Does not address the need for early activation of key personnel for rapid decision-making for definitive haemorrhage control in patients with exsanguinating haemorrhage |

| Unified protocol | (1) Effective in ensuring early decision-making for definitive haemorrhage control as well; (2) Addresses the issues which lead to a delay in transferring the patient from ED to OT/IR; and (3) Benefits are not physician or time dependent | (1) Combines benefits of both Code Crimson and Red Blanket protocols. Reduces time from ED to definitive haemorrhage control in a patient with exsanguinating trauma; (2) Communication between various multi-disciplinary coordinators occurs rapidly and seamlessly; (3) Minimizes the number of calls that need to be made by the ED and trauma teams to various stakeholders and focus on resuscitation; and (4) Effective resource allocation and utilization | (1) Hesitancy of staff to adopt new workflow; (2) Logistical challenges of integrating the new unified workflow in the existing trauma system; and (3) Training requires time and resources that can impact work schedules and budget |

In conclusion, Code Crimson is aimed at rapid decision-making for definitive haemorrhage control, while Red Blanket addresses the factors and processes causing delay and aims to get the patient rapidly to OT/IR for definitive haemorrhage control. Code Crimson and Red Blanket have been adapted separately in some hospitals in Australasia, but not as one merged process. Both these processes complement each other. Hence, unifying these processes into a single workflow as suggested would ensure combined benefits of both these protocols, and ascertain that these benefits are not physician or time dependent. Considering the overlap between these two protocols, which both aimed at reducing the time from ED to definitive haemorrhage control in a patient with exsanguinating trauma, healthcare leaders should consider introducing these quality improvement strategies and a coordinated, unified processes within their respective trauma framework. This will eventually aim to improve the care for the complex trauma patients requiring multi-disciplinary care and definitive haemorrhage control.

| 1. | Purdy EI, McLean D, Alexander C, Scott M, Donohue A, Campbell D, Wullschleger M, Berkowitz G, Winearls J, Henry D, Brazil V. Doing our work better, together: a relationship-based approach to defining the quality improvement agenda in trauma care. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lamb CM, MacGoey P, Navarro AP, Brooks AJ. Damage control surgery in the era of damage control resuscitation. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tovmassian D, Hameed AM, Ly J, Pathmanathan N, Devadas M, Gomez D, Hsu JM. Process measure aimed at reducing time to haemorrhage control: outcomes associated with Code Crimson activation in exsanguinating truncal trauma. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:481-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Grabs AJ, May AN, Fulde GW, McDonell KA. Code crimson: a life-saving measure to treat exsanguinating emergencies in trauma. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:523-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pothiawala S, Friedericksen M, Civil I. Activating Code Crimson in the emergency department: Expediting definitive care for trauma patients with severe haemorrhage in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2022;51:502-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee DJK, Kang ML, Christie LMJ, Lim WW, Tay DX, Patel S, Goo JTT. Improving trauma care in exsanguinating patients with CHOP (critical haemorrhage to operating-room patient) resuscitation protocol-A cumulative summation (CUSUM) analysis. Injury. 2021;52:2508-2514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | NSW Institute of Trauma and Injury Management. Clinical guidelines: Trauma 'Code Crimson' pathway. Available from: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/networks/institute-of-trauma-and-injury-management/clinical/trauma-guidelines/Guidelines/trauma-code-crimson-pathway. |

| 8. | Mohamed F, Grinlinton M, Henshall K, Cox M, MacCormick AD. The Red Blanket Protocol in a tertiary centre in Aotearoa New Zealand: does this trauma protocol improve time to surgery and clinical outcomes? ANZ J Surg. 2022;92:1714-1723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gruen RL, Jurkovich GJ, McIntyre LK, Foy HM, Maier RV. Patterns of errors contributing to trauma mortality: lessons learned from 2,594 deaths. Ann Surg. 2006;244:371-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Davidson GH, Maier RV, Arbabi S, Goldin AB, Rivara FP. Impact of operative intervention delay on pediatric trauma outcomes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:162-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Queensland Government. Rapid Transfer (Red Blanket) of the trauma patient from the department of emergency medicine to the operating room. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/document/145152649/Red-Blanket-Protocol-RBWH.pdf. |

| 12. | Metro South Health. Time critical care red blanket transfer from emergency department to operating theatre. Princess Alexandra Hospital procedure manual. Available from: http://www.emergpa.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/Time-Critical-Care-Red-Blanket-Guideline-V3-3.pdf. |

| 13. | Grant K, Handy M. Reducing the transfer delay of the trauma patient from the Emergency Department to the Operating Room. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2010;13:147. [DOI] [Full Text] |