Published online Mar 9, 2025. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v14.i1.97006

Revised: October 24, 2024

Accepted: November 19, 2024

Published online: March 9, 2025

Processing time: 205 Days and 3 Hours

Understanding a patient's clinical status and setting priorities for their care are two aspects of the constantly changing process of clinical decision-making. One analytical technique that can be helpful in uncertain situations is clinical judg

To examine the ethical issues healthcare professionals faced during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the factors affecting clinical decision-making.

This pilot study, which means it was a preliminary investigation to gather information and test the feasibility of a larger investigation was conducted over 6 months and we invited responses from clinicians worldwide who managed patients with COVID-19. The survey focused on topics related to their professional roles and personal relationships. We examined five core areas influencing critical care decision-making: Patients' personal factors, family-related factors, informed consent, communication and media, and hospital administrative policies on clinical decision-making. The collected data were analyzed using the χ2 test for categorical variables.

A total of 102 clinicians from 23 specialties and 17 countries responded to the survey. Age was a significant factor in treatment planning (n = 88) and ventilator access (n = 78). Sex had no bearing on how decisions were made. Most doctors reported maintaining patient confidentiality regarding privacy and informed consent. Approximately 50% of clinicians reported a moderate influence of clinical work, with many citing it as one of the most important factors affecting their health and relationships. Clinicians from developing countries had a significantly higher score for considering a patient's financial status when creating a treatment plan than their counterparts from developed countries. Regarding personal experiences, some respondents noted that treatment plans and preferences changed from wave to wave, and that there was a rapid turnover of studies and evidence. Hospital and government policies also played a role in critical decision-making. Rather than assessing the appropriateness of treatment, some doctors observed that hospital policies regarding medications were driven by patient demand.

Factors other than medical considerations frequently affect management choices. The disparity in treatment choices, became more apparent during the pandemic. We highlight the difficulties and contradictions between moral standards and the realities physicians encountered during this medical emergency. False information, large patient populations, and limited resources caused problems for clinicians. These factors impacted decision-making, which, in turn, affected patient care and healthcare staff well-being.

Core Tip: Ethical principles guide healthcare practitioners (HCPs) in their everyday practice. However, in unstable situations such as pandemics, the principles of good decision-making can often conflict, leaving clinicians perplexed about the best course of action. HCPs faced ethical dilemmas involving duty of care, justice, and dignity. In the absence of evidence, clinical judgments were made using value-based approaches. The pandemic exposed gaps in health care availability, causing providers to experience high levels of stress and worry. It is important to view this as an opportunity to strengthen public health funding policies.

- Citation: Vadi S, Sanwalka N, Thaker P. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on factors influencing their critical care decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international pilot survey. World J Crit Care Med 2025; 14(1): 97006

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v14/i1/97006.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v14.i1.97006

The clinical decision-making process is dynamic, and involves comprehending the clinical status of patients and prioritizing their care. Clinical judgment is an analytical process that can be advantageous in times of uncertainty. When emergencies arise, clinicians must handle conflicting information, limited decision-making time, and long-term tradeoffs[1].

The World Health Organization declared the coronavirus outbreak a global public health emergency on January 30, 2020[2] and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak a pandemic[3] on March 11, 2020, after it was first reported in China. The healthcare system was unprepared and quickly overwhelmed by the large number of critically ill patients. A survey[4] including 29 countries with 852 physicians from 44 specialties showed that perceived expertise and publications, sex, geographical origin, medical specialty, and its implications influenced clinical decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic. The increasing demand for ventilators made rationing equipment[5] a difficult decision. Vulnerable groups of patients, specifically older individuals, were impacted by admission to intensive care unit (ICU) and provision of life-support. Hospitals had to limit visitation policies to reduce the transmission of contagion from an infection control perspective. Health-care provider (HCP) and next-of-kin exchanged minimal information in some instances.

The pandemic caused considerable misinformation to circulate in the media, resulting in increased fear and anxiety among the public. The spread of incorrect information regarding the available treatment options caused patients and their families to demand these treatments during hospitalization. At times, the public’s response to media information unsupported by credible evidence was alarming.

The contagion negatively impacted healthcare workers’ personal and professional relationships, creating a social disconnect. Long working hours caused feelings of isolation and alienation, leading to a higher incidence of depression among ICU workers. The decisions made by HCPs during these challenging times will impact on them for years by affecting their physical and mental well-being. In a mental health survey[6] of ICU and emergency room front-liners, 21.6% had post-traumatic stress disorder, 88.6% had moderate to high stress, 16.3% had anxiety, and 59.5% had poor sleep.

Patients who were afflicted were stigmatized even after they were healed. In health emergencies, conflicts can arise between public rights (basic social rights) and patient privacy or confidentiality (individual rights). For health surveillance purposes, public health authorities (limited to authorized personnel) were provided feedback on patient identities. Hospitals were overwhelmed with patients, and ICU environments became ethically challenging. Early data from mainland China revealed a case-fatality ratio of 1.38% (1.2-1.53) with higher ratios in those aged ≥ 80 years (13.4% [11.2-15.9]), vs for those ≥ 60 years (6.4% [5.7-7.2]) vs for those aged < 60 years (0.32% [0.27-0.38])[7]. European Center for Disease Prevention and Control reported a 28% death rate in Belgium[8] with a risk of long-term care facility residents unable to secure ICU beds. Patients aged 65 or over were at greater risk of death for this reason. This indicates a higher propensity for death among the older population.

During the initial pandemic, no guidelines or algorithms existed for decision-making. With time, as clinical knowledge evolved, patient management improved and progress was achieved in the surveillance system. Differences in healthcare organizations, exist among countries, depending on their societal and legal relevance[9,10]. Health systems were overstretched to cater to the needs of patients with COVID-19. Interferences and uncertainties were created in the delivery of care. What level of influence do age, sex, and financial status have on clinicians’ recommendations? Did hospital policies affect preferences owing to these factors?

We acknowledge that efficient patient-HCP interactions are essential for achieving effective clinical outcomes. If this is true in routine and non-emergency settings, the factors affecting the interactions between patients and clinicians will be more significant in emergencies, such as the case of pandemic. Exercising good judgement in decision-making for complex COVID-19 cases during this time was fraught with high stakes, along with the need to make quick decisions associated with uncertain outcomes. In this study, we examine the factors that impacted clinical decision-making and the ethical challenges faced by HCPs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this pilot study, we conducted a cross-sectional online survey between May 27, 2021, and November 14, 2021. HCPs who managed patients with SARS CoV-2 infection were included in the survey regardless of their specialty. The investigators used a convenience sampling method to contact 500 clinicians through social networks such as WhatsApp and X, professional networks, and personal contacts. 102 clinicians responded to the survey (response rate of approximately 21.6%). Anonymity was maintained and our study followed the ‘Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology’ guidelines for observational studies.

Data was collected using Google Forms structured questionnaire. Details of the survey, including the purpose and need of the study, were provided to the participants in the description section. Informed consent was obtained via Google Forms prior to data collection.

Demographic variables such as age range, sex, and professional status, including place of work, specialty, and country of work were collected.

A structured questionnaire was developed to collect data. After conducting a literature review and brainstorming sessions, the authors identified five core areas that influence critical care decision-making: Patients' personal factors, family-related factors, informed consent, communication and media, and hospital administrative policies regarding clinical decision-making. The goal was to minimize the number of questions in order to maximize the response rate. The questionnaire was written in English and used a 5-point rating scale (ranging from "no influence" to "most important factor"). Information on patients' personal factors (such as age and sex), family-related factors (including financial status and the influence of accompanying family members), hospital administration-related factors (such as time of arrival, hospital policies, and clinical research), and communication-related factors (such as social media information and language of communication) were gathered. Additionally, a 5-point scale (ranging from "never" to "always") was used to collect details on the influence of patient privacy and informed consent policies. The questionnaire also included three questions about the impact of clinical work on professional and personal relationships and, personal health. This was done to assess the impact of COVID-19 on clinicians’ health and interpersonal relationships. The questionnaire is available in the Supplementary material.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States, 2017). The rating scales were coded as follows: No influence/never = 1, very little influence/mostly not = 2, moderate influence/sometimes = 3, one of the important factors/mostly = 4, and most important factor/always = 5.

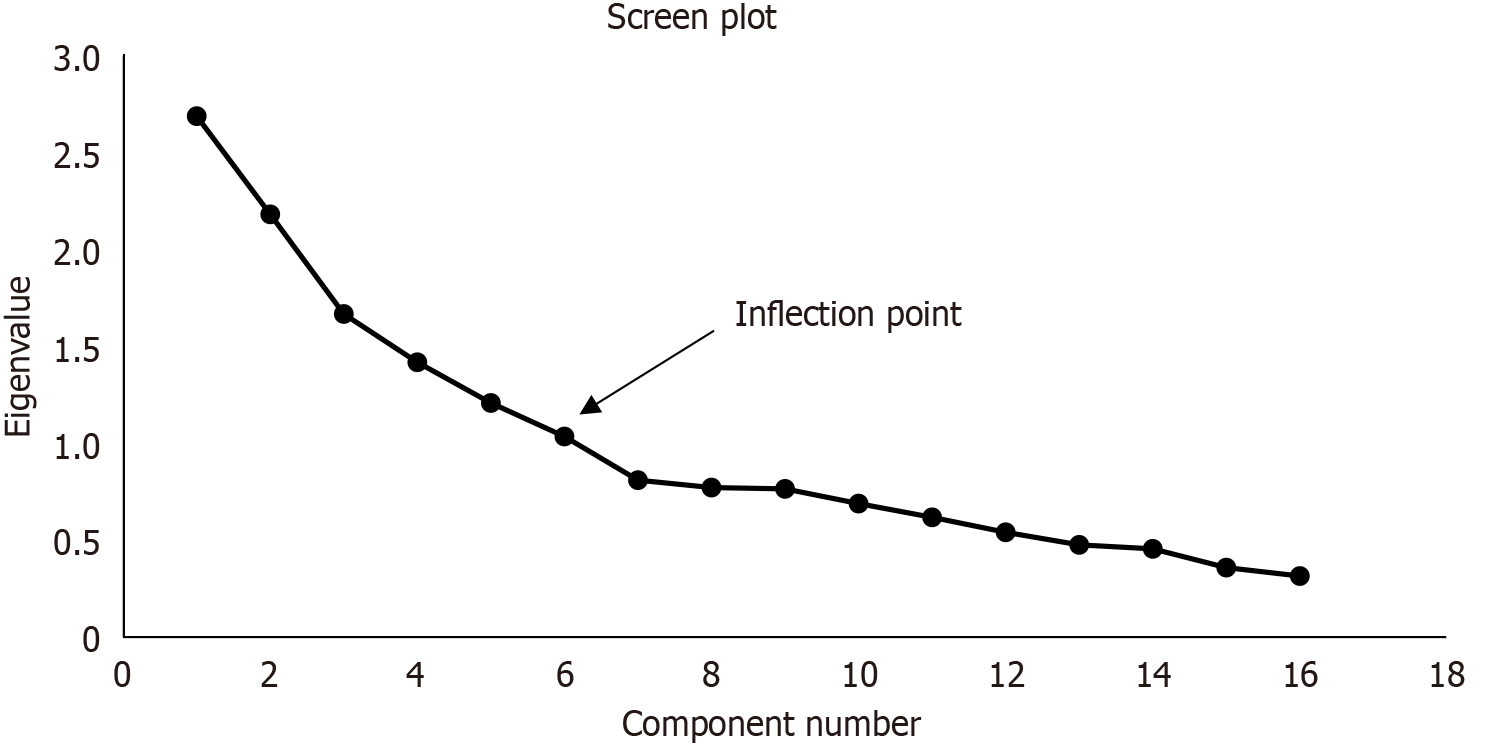

After the questionnaire was formulated, its initial validity was tested using the face validity method. Five doctors actively involved in managing patients with COVID-19 patients were asked to provide feedback on the format, content, and clarity of the questionnaire. They confirmed that the questions were easy to understand and suggested minor modifications, which were incorporated. The reliability of the 16 questions used to assess the influence of the factors on decision-making was then evaluated using Cronbach's alpha. Additionally, principal axis factoring was conducted to determine the variability of the collected data. The principal component analysis results are presented as a scree plot and a rotated structure matrix.

Survey data are presented as frequency (%) or mean ± SD. The Mann Whitney U test was used to analyze differences ratings provided by clinicians from developed and developing countries. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Cronbach’s alpha was 0.783 indicating the internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire were close to being in the good range.

A principal axis factoring analysis was conducted on the 16 questions that measured the impact of different factors on decision making in 102 participants. The overall Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure was 0.626, indicating a moderate level of sampling adequacy. Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a statistically significant result (P < 0.005), indicating the data were suitable for factor analysis.

The analysis revealed that six components had eigenvalues greater than one, and these explained 16.8%, 13.6%, 10.4%. 8.9%, 7.6% and 6.5% of the total variance, respectively. Visual inspection of the scree plot indicated that five components should be retained (Figure 1). Six components were retained as they met the interpretability criteria. The six components accounted for 63.7% of the total variance. The rotated matrix exhibited a “simple structure.” Data interpretation was as follows: (1) Informed consent on; component; (2) Patient related factors; component; (3) Patients’ financial status and family presence as well as time of arrival; component; (4) Research-related; component; and (5) Hospital administrative policies and component 6 communication (Table 1).

| Rotated component coefficients for components | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Obtain informed consent | 0.785 | |||||

| Accurately inform patient’s family regarding patient’s condition | 0.711 | |||||

| Age influence on treatment | 0.883 | |||||

| Give priority to patient’s interests over other interests in the treatment plan | 0.410 | |||||

| Age influence on decision to access ventilator | 0.407 | |||||

| Sex influence on treatment | 0.302 | |||||

| Family member presence influence on treatment plan | 0.624 | |||||

| Patient’s financial status influence on treatment plan | 0.568 | |||||

| Time of arrival influence on treatment plan | 0.415 | |||||

| Maintain privacy of patient’s information | 0.538 | |||||

| Clinical research data collection influence on patient treatment | 0.500 | |||||

| Give accurate information about risk/ benefit of treatment plan | 0.416 | |||||

| Hospital policies and decisions helpful in treatment plan | 0.652 | |||||

| Hindrance of hospital policies and decisions on treatment plan | 0.427 | |||||

| Language influence treatment | 0.466 | |||||

| Social media information influence on treatment plan | -0.385 | |||||

Table 2 presents the demographic information of the participants. Most participants (70.6%) were male, and 49% were aged 46 years and older. The data was collected from a total of 102 clinicians representing 23 specialties and 17 countries. The distribution of respondents is as follows: 55 from India, 11 from Canada, 5 each from the United States and the United Arab Emirates, 4 from Italy, 3 each from Australia and Nepal, 2 each from Brazil, Pakistan, Romania, Belgium, and Spain, and 1 each from Britain, Germany, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, and Saudi Arabia.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 72 | 70.6 |

| Female | 30 | 29.4 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 31-35 | 7 | 6.9 |

| 36-40 | 13 | 12.7 |

| 41-45 | 32 | 31.4 |

| 46-50 | 20 | 19.6 |

| > 50 | 30 | 29.4 |

| Hospital department | ||

| Emergency room | 3 | 2.9 |

| COVID ICU | 57 | 55.9 |

| Non-COVID ICU | 13 | 12.7 |

| Ward/floor | 29 | 28.4 |

Various factors influencing decision making as reported by clinicians, are presented in Tables 3 and 4. Language (n = 98) and sex (n = 90) were reported as factors that had no influence on their clinical decision making. Conversely, age was one of the factors that most influenced the treatment plan (n = 88), as well as ventilator accessibility (n = 78) (Table 3).

| No influence | Very little influence | Moderate influence | One of the important factors | Most important factor | |

| Patient-related factors | |||||

| Age influence on treatment | 14 (13.7) | 21 (20.6) | 33 (32.4) | 30 (29.4) | 4 (3.9) |

| Age influence on decision to access ventilator | 24 (23.5) | 16 (15.7) | 36 (35.3) | 23 (22.5) | 3 (2.9) |

| Sex influence on treatment | 90 (88.2) | 8 (7.8) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Patient’s family and financial status-related factors | |||||

| Patient’s financial status influence on treatment plan | 60 (58.8) | 15 (14.7) | 23 (22.5) | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1) |

| Family member presence influence on treatment plan | 47 (46.1) | 39 (38.2) | 9 (8.8) | 5 (4.9) | 2 (2) |

| Hospital administration-related factors | |||||

| Time of arrival influence on treatment plan | 39 (38.2) | 18 (17.6) | 19 (18.6) | 21 (20.6) | 5 (4.9) |

| Hospital policies and decisions helpful in treatment plan | 20 (19.6) | 31 (30.4) | 29 (28.4) | 16 (15.7) | 6 (5.9) |

| Hindrance of hospital policies and decisions in treatment plan | 41 (40.2) | 39 (38.2) | 16 (15.7) | 4 (3.9) | 2 (2) |

| Clinical research data collection influence on patient treatment | 43 (42.2) | 30 (29.4) | 13 (12.7) | 8 (7.8) | 8 (7.8) |

| Communication-related factors | |||||

| Social media information influence on treatment plan | 59 (57.8) | 33 (32.4) | 9 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Language influence on treatment | 98 (96.1) | 3 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Never | Mostly not | Sometimes | Mostly | Always | |

| Accurately inform patient’s family regarding patient’s condition | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.9) | 44 (43.1) | 52 (51) |

| Obtain informed consent | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 10 (9.8) | 45 (44.1) | 46 (45.1) |

| Give accurate information about risk/benefit of treatment plan | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 8 (7.8) | 38 (37.3) | 55 (53.9) |

| Maintain privacy of patient’s information | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 (17.6) | 84 (82.4) |

| Give priority to patient’s interests over other interests in the treatment plan | 2 (2) | 3 (2.9) | 6 (5.9) | 27 (26.5) | 66 (64.7) |

Almost all doctors maintained patient privacy and confidentiality. Most clinicians obtained most of the time or always before making critical care decisions (Table 4).

Table 5 shows the influence of clinical work on clinicians’ health and interpersonal relationships. Approximately 50% of clinicians reported a moderate influence, with many citing it as one of the most important factors affecting their health and relationships. This suggests that clinical work had a moderate to significant impact on the well-being and interpersonal dynamics of clinicians.

| Never | Mostly not | Sometimes | Mostly | Always | |

| Clinical work affects professional relationships | 24 (23.5) | 36 (35.3) | 28 (27.5) | 13 (12.7) | 1 (1) |

| Clinical work affects family relationships | 19 (18.6) | 28 (27.5) | 27 (26.5) | 23 (22.5) | 5 (4.9) |

| Clinical work affects health | 18 (17.6) | 33 (32.4) | 33 (32.4) | 12 (11.8) | 6 (5.9) |

We analyzed the differences between clinicians from developed and developing countries (Table 6) to determine whether a country's level of development impacted their answers. Clinicians from developed countries had a significantly higher score for considering age when making decisions about access to ventilators and for recognizing how clinical work can affect professional relationships than, clinicians from developing countries (P < 0.05). Conversely, clinicians from developing countries had a significantly higher score for considering a patient's financial status when creating a treatment plan, involving family members in the treatment plan, accurately informing the patient's family about their condition, and obtaining informed consent than, clinicians from developed countries (P < 0.05).

| Developing country (n = 64) | Developed country (n = 38) | P value | |

| Patient-related factors | |||

| Age influence on treatment | 2.75 ± 1.11 | 3.13 ± 1.04 | 0.063 |

| Age influence on decision to access ventilator | 2.45 ± 1.17 | 3.00 ± 1.07 | 0.017 |

| Sex influence on treatment | 1.13 ± 0.42 | 1.29 ± 0.84 | 0.320 |

| Patient’s family and financial status-related factors | |||

| Patient’s financial status influence on treatment plan | 1.95 ± 0.97 | 1.50 ± 0.83 | 0.001 |

| Family member presence influence on treatment plan | 2.08 ± 0.97 | 1.13 ± 0.67 | 0.007 |

| Hospital administration-related factors | |||

| Time of arrival influence on treatment plan | 2.53 ± 1.27 | 2.08 ± 1.34 | 0.076 |

| Hospital policies and decisions helpful in treatment plan | 2.73 ± 1.14 | 2.32 ± 1.12 | 0.064 |

| Hindrance of hospital policies and decisions in treatment plan | 1.83 ± 0.95 | 2.00 ± 0.93 | 0.247 |

| Clinical research data collection influence on patient treatment | 2.13 ± 1.25 | 2.05 ± 1.27 | 0.770 |

| Communication-related factors | |||

| Social media information influence on treatment plan | 1.53 ± 0.69 | 1.55 ± 0.83 | 0.918 |

| Language influence on treatment | 1.02 ± 0.13 | 1.16 ± 0.68 | 0.110 |

| Patient privacy and informed consent | |||

| Accurately inform patient’s family regarding patient’s condition | 3.55 ± 0.62 | 3.26 ± 0.64 | 0.018 |

| Obtain informed consent | 3.48 ± 0.71 | 3.08 ± 0.59 | 0.001 |

| Give accurate information about risk/benefit of treatment plan | 3.53 ± 0.67 | 3.29 ± 0.69 | 0.057 |

| Maintain privacy of patient’s information | 1.78 ± 0.42 | 1.89 ± 0.31 | 0.148 |

| Give priority to patient’s interest over other interests in the treatment plan | 4.56 ± 0.79 | 4.45 ± 0.76 | 0.286 |

| Effect on health and interpersonal relationships | |||

| Clinical work affects professional relationships | 2.13 ± 0.92 | 2.66 ± 1.07 | 0.014 |

| Clinical work affects family relationships | 2.56 ± 1.15 | 2.87 ± 1.17 | 0.196 |

| Clinical work affects health | 2.69 ± 1.05 | 2.34 ± 1.15 | 0.092 |

An open-ended question was posed to understand the factors influencing clinicians’ critical care decision-making: "Do you have any specific comments or experiences to share regarding the factors that influenced your treatment plan?"

We have categorized some of the main findings and included comments from the physicians: One factor that affecting critical decision making was the uncertainty in medical science, as knowledge in the field constantly evolves. Some physicians noted that treatment plans and preferences changed from wave to wave, and that there was a rapid turnover of studies and evidence. Others mentioned that while their treatment plans were evidence-based, extra effort was required to sift through the vast amount of literature to make the best decisions. Some physicians also expressed frustration because of the lack of accurate guidelines and limited evidence. Hospital and government policies also played a role in critical decision-making. Some physicians noted that hospital policies on medication were influenced by patient demand rather than by the appropriateness of the treatment. Others mentioned they had to consider resource limitations in resources and the expected burden on the patient and healthcare system. Some physicians also expressed frustration with political and government interference in their decision-making. Patient and family-centred aspects were also important factors in critical decision-making. Age was a significant factor, especially during the second wave, when resources were scarce. Effective communication with patients and their families was viewed as crucial, and some physicians noted that visitor restrictions during the pandemic made this challenging. The absence or presence of family and social support also played a role in the rehabilitation and discharge possibilities of patients.

Healthcare equity is crucial for a population that is limited from the individual patient perspective. In this study, we analyzed the influence of patient’s age, sex, financial status, time of arrival, hospital policies, and the presence of family members on clinical decision-making.

The magnitude and complexity of events necessitate a shift from an individual-centered to a society-centered approach. Older individuals are prone to more severe infections with unfavorable outcomes[11] owing to age-related physiological changes and impaired immunity. Age is commonly regarded as a marker of comorbidity and frailty[12]. When demand exceeds the supply, the healthcare system responds by shifting from conventional to crisis care[13]. When triage shifts from conventional to crisis-based triage to save health-related quality of life years, chronological age matters[14,15].

A gender gap exists in resource management, and the pandemic has contributed to the widening of sex disparities. Understanding the impact inequality in healthcare distribution based on sex and gender is critical. Heterogeneity in decision-making and its implementation was noted in areas such as the influence of time to arrival on treatment plans, the extent to which informed consent was obtained, and communication of clinical progress to family members among respondents from various countries. As the demand for ventilators increased, difficult decisions regarding rationing equipment had to be made. ICU admission and criteria for providing life support had a disproportionate impact on vulnerable patients, particularly the older adults, as observed in our study.

HCPs had to consider prioritizing patients with the best chance of survival over those with low odds. This has sparked intense debate regarding the right for everyone to receive healthcare[16].

Bioethical principles can conflict in pandemic settings. The pandemic has resulted in unequal access to basic health services. Pandemics and other health emergencies (e.g., the Ebola crisis in 2014) require swift mobilization of funds to ensure appropriate use for the intended at-risk population. This is vital for minimizing gaps in public sector hospitals and protecting vulnerable populations[17]. Hence, we investigated the potential impact of a patients’ financial status on the treatment they received.

Patient care was directly impacted by decisions made by hospital’s administrative teams. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital policies that approved certain medications and treatments to be administered to patients based on the patient’s wants and preferences appeared appealing to the public, but negatively influenced clinicians’ decision-making. The conventional belief is that resources should be distributed equitably. However, given the overwhelming emergency resource-allocation decisions had to be made regarding scarcity, leading to the need to determine who should be treated. The ethical premise of rationing must be objective and unbiased[18]. The typical approach to treatment (the principle of distributive justice)[19] is to treat the sickest person first, or on a first-come, first-served basis, rather than VIPs. Rationing shifted this decision away from the disadvantaged.

Efficient communication is necessary to ensure the dissemination of reliable information, establish trusting relationships with families, and prevent paternalistic and negative accusations.

This survey from India is the first to examine the factors influencing HCPs decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic. Age was a significant factor in treatment decisions for 29.4% of the respondents, with 22.5% of the treating physicians citing age as a factor in decisions regarding ventilator access. Those who were expected to live longer, according to the age criteria, were given priority. When all patient-related factors were considered, age appeared to be a significant variable in determining whether a patient was referred for ICU admission. The availability of resources in an overburdened healthcare system will likely shape these decisions.

Autonomy was also identified as a crucial factor in clinical decision-making, with 4% of the respondents recognizing its importance, and 15.7% reporting that hospital policies and decisions moderately influenced their treatment plans. However, most clinicians (64.7%) prioritized patients’ interests over other factors in their treatment plans.

Guidelines[20] for the family-centered care of ICU patients emphasize the importance of incorporating patient and family perspectives. Participation in team rounds was encouraged to improve patient and family satisfaction with communication. However, the realities of a health emergency often conflict with the ideals that can be advocated and implemented during non-emergency clinical encounters.

Patient and family involvement in decision-making was limited, and phone calls to update families on the patient's clinical status were only made once a day in some hospitals. These discussions gave families an idea of the patient's criticality and allowed them time to consider difficult decisions, if necessary. Follow-up calls were made in case of destabilization, and patients were allowed to communicate with their families via personal mobile phones. In some cases, video calls were arranged for sedated patients on ventilators, those with communication challenges, and children.

This is an opportunity to learn about and improve health financing policies for the general public.

A new pandemic has brought about ethical challenges similar to those faced in any global health emergency. Without robust evidence, clinical decisions must be based on principles that require value judgements. Health governance varies among countries, leading to differences in ethical perceptions influenced by societal and legal distinctiveness. Decisions regarding critical care resource allocation, are often made using practical approaches. Clinicians may encounter ethical predicaments related to duty of care, fairness, and dignity.

Duty of care: During the pandemic, when ethical considerations were not clarified by public health authorities, there were inconsistencies in the outlined policies. Clinicians had to rationalize when making difficult decisions, such as triage and rationing equipment, especially ventilators, and dealing with choices of life vs death. This responsibility through deliberation[21] was based on the intention to do well, even when incorrect information was disseminated in the media. Impulsive research uploaded to preprint medical servers without peer review also raise ethical issues. Several treatments commissioned were without a strong and logical scientific basis and served to comply with the newly formed chain of command not involved in direct patient care. The courses of action were considered as ethically appropriate because they were legally permissible. Despite morally sound deliberations, undesirable outcomes have left HCPs with a sense of guilt.

Fairness: Fairness through impartiality means that all patients, irrespective of age, sex, and financial status, have an equal right to treatment. However, given the pandemic, this has not been the case in several parts of the world. Rationing policies vary according to the institutional policies and legal systems.

Dignity: Interference by the mass media to circulate sensational news impinged on the privacy of patients, even after their deaths. This has impacted nations across the board and their corresponding health care systems.

Unprecedented work intensity and shortage of ICU beds and ventilators have caused clinicians to make disturbing choices for management decisions. Utilitarian ethics considered at a group level have taken antecedence to individual ethics. Many of these have been polarizing in contrast to their basic ethical principles. These effects will persist for years to come.

Interprofessional power gaps: For some respondents, centralized institutional decision-making norms have hampered their bedside decision-making. These power differentials affect patient care during health emergencies.

The survey was disseminated through email and social media, leading to selection bias. This self-reporting survey is prone to response bias. Given the sample size, the differences in responses between geographical areas should be interpreted cautiously. This pilot study was conducted during the peak of the pandemic. Owing to ethical considerations and the timing of the study, we did not receive a significant response. However, larger confirmatory studies should be conducted based on our findings.

This survey is the first of its kind in India and provides insights into the factors that influencing critical decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic. The target respondents were a diverse group of HCPs who actively managed patients with COVID-19. Using a close-ended questionnaire allowed for pooling responses from a sample of pandemic respondents. The survey results highlight the challenges faced when providing family centric care for ICU patients. Our study aimed to gather information about clinicians' responses to treating patients during the pandemic and draw attention to the ethical dimensions of these decisions.

Clinical decision-making is essential part to patient care, particularly during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinicians face difficulties owing to the large number of patients, limited resources, and false information. These elements affect decision-making, which in turn affects patient care and the welfare of healthcare personnel. HCPs experienced high levels of stress and worry because of the pandemic, which has exposed gaps in healthcare availability. Serious long-term consequences to bodily and mental well-being were evident. This emphasizes the importance of helping medical workers through trying times. This poll sheds light on the choices made by HCPs worldwide during a medical emergency. The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted and rewritten the professional duties and relationships of clinicians.

| 1. | Redelmeier DA, Ferris LE, Tu JV, Hux JE, Schull MJ. Problems for clinical judgement: introducing cognitive psychology as one more basic science. CMAJ. 2001;164:358-360. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Worldometers. Coronavirus statistics. January 2020 Coronavirus News Updates. Worldometer. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. |

| 3. | Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:157-160. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2619] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Martínez-Sanz J, Pérez-Molina JA, Moreno S, Zamora J, Serrano-Villar S. Understanding clinical decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional worldwide survey. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;27:100539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | White DB, Lo B. A Framework for Rationing Ventilators and Critical Care Beds During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1773-1774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 99.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vadi S, Shah S, Bajpe S, George N, Santhosh A, Sanwalka N, Ramakrishnan A. Mental Health Indices of Intensive Care Unit and Emergency Room Frontliners during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Pandemic in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022;26:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Verity R, Okell LC, Dorigatti I, Winskill P, Whittaker C, Imai N, Cuomo-Dannenburg G, Thompson H, Walker PGT, Fu H, Dighe A, Griffin JT, Baguelin M, Bhatia S, Boonyasiri A, Cori A, Cucunubá Z, FitzJohn R, Gaythorpe K, Green W, Hamlet A, Hinsley W, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, Riley S, van Elsland S, Volz E, Wang H, Wang Y, Xi X, Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Ferguson NM. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:669-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2689] [Cited by in RCA: 2222] [Article Influence: 444.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Increase in fatal cases of COVID-19 among long-term care facility residents. 2020. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/2019-ncov-background-disease. |

| 9. | Redaniel MT, Laudico A, Mirasol-Lumague MR, Gondos A, Pulte D, Mapua C, Brenner H. Cancer survival discrepancies in developed and developing countries: comparisons between the Philippines and the United States. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:858-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Austin S, Murthy S, Wunsch H, Adhikari NK, Karir V, Rowan K, Jacob ST, Salluh J, Bozza FA, Du B, An Y, Lee B, Wu F, Nguyen YL, Oppong C, Venkataraman R, Velayutham V, Dueñas C, Angus DC; International Forum of Acute Care Trialists. Access to urban acute care services in high- vs. middle-income countries: an analysis of seven cities. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:342-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | ICNARC. ICNARC report on COVID-19 in critical care 15 may 2020. Available from: https://www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports. |

| 12. | James FR, Power N, Laha S. Decision-making in intensive care medicine - A review. J Intensive Care Soc. 2018;19:247-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jecker NS. Too old to save? COVID-19 and age-based allocation of lifesaving medical care. Bioethics. 2022;36:802-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rhodes R. Justice and Guidance for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Bioeth. 2020;20:163-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, Zhang C, Boyle C, Smith M, Phillips JP. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2049-2055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1844] [Cited by in RCA: 1870] [Article Influence: 374.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mannelli C. Whose life to save? Scarce resources allocation in the COVID-19 outbreak. J Med Ethics. 2020;46:364-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | De Foo C, Verma M, Tan SY, Hamer J, van der Mark N, Pholpark A, Hanvoravongchai P, Cheh PLJ, Marthias T, Mahendradhata Y, Putri LP, Hafidz F, Giang KB, Khuc THH, Van Minh H, Wu S, Caamal-Olvera CG, Orive G, Wang H, Nachuk S, Lim J, de Oliveira Cruz V, Yates R, Legido-Quigley H. Health financing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic and implications for universal health care: a case study of 15 countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11:e1964-e1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Iserson KV. Healthcare Ethics During a Pandemic. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21:477-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vincent JL, Creteur J. Ethical aspects of the COVID-19 crisis: How to deal with an overwhelming shortage of acute beds. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9:248-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, Puntillo KA, Kross EK, Hart J, Cox CE, Wunsch H, Wickline MA, Nunnally ME, Netzer G, Kentish-Barnes N, Sprung CL, Hartog CS, Coombs M, Gerritsen RT, Hopkins RO, Franck LS, Skrobik Y, Kon AA, Scruth EA, Harvey MA, Lewis-Newby M, White DB, Swoboda SM, Cooke CR, Levy MM, Azoulay E, Curtis JR. Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:103-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 719] [Cited by in RCA: 937] [Article Influence: 117.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bustan S, Nacoti M, Botbol-Baum M, Fischkoff K, Charon R, Madé L, Simon JR, Kritzinger M. COVID 19: Ethical dilemmas in human lives. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27:716-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |