INTRODUCTION

Endoscopy performed in the intensive care unit (ICU) had different aims and management than elective endoscopy. Often, patients are hemodynamically unstable and have multiple comorbidities that require careful consideration before the procedure. The majority of outpatient colonoscopies are for screening for colorectal cancer. The majority of inpatient colonoscopies are for rectal bleeding, colitis, and decompression of bowel obstruction[1]. In a retrospective study by Cremone et al[2], 295 of 603 patients who underwent urgent colonoscopy in the hospital were ICU patients[2]. Rectal bleeding, melena, colonic distension, volvulus, pseudo-obstruction and diarrhea were common indications for urgent bedside colonoscopy.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in outpatient is often for refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease, anemia, weight loss, and diarrhea. Whereas inpatient EGD includes hematemesis, melena, symptomatic anemia, abnormal inpatient imaging findings, and dysphagia[3]. This mini review aims to identify the indications, common diagnoses, challenges, outcomes and anesthesia considerations in bedside endoscopy procedures.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF GUT IN ICU

The gastrointestinal (GI) organ system includes intestinal epithelium, mucosal immune system, enteric nervous system, microflora of the gut lumen. Impaired function can occur at any level of the gut. Patients in the ICU often have Impaired intestinal absorption, and slow gut motility, imbalance in endocrine response, increased intra-abdominal pressure, changes in gut microbiome, increased gut translocation, impaired mesenteric perfusion, altered mucosal barrier integrity, impaired absorption of fluids, electrolytes and nutrients and altered mucosal immune activity[4,5]. These pathophysiological changes may be from multi organ failure in the ICU. These changes lead to malnutrition, cholestasis, gastroparesis, Ileus, Bowel edema, oral feed intolerance, gastric ulceration, decreased intestinal blood supply, Bacterial translocation, GI infections, lactic acidosis, GI reflux. Complications from altered gut pathophysiology led to Ogilvie’s syndrome, GI tract perforation, Massive GI bleeding, sepsis, abdominal compartment syndrome, bowel ischemia and poor clinical outcomes[4,5].

CLINICAL INDICATIONS FOR GI ENDOSCOPY IN THE ICU

Patients in the ICU can develop new onset GI bleeding during the ICU admission. This may be due to multiorgan failure, ICU therapies, and the stress of ICU stay. The commonest noted causes for new onset bleeding in the ICU include peptic ulcer, gastritis, esophagitis, variceal bleeding, Mallory Weiss tear, vascular lesions (Angio ectasia, dieulafoy’s), and tumors. Penaud et al[6] in their study of 255 patients who underwent EGD at the bedside in the ICU for indications of anemia, melena, shock, and hematemesis, found ulcers in 23%, esophagitis in 19%, and gastritis in 13%[6]. Based on these findings, the authors derived the SUGIBI score and found that a score < 4 had a negative predictive value for hemostatic intervention on endoscopy. The SUGIBI score includes male gender, smoking history, cirrhosis and hematochezia, which scored one point each, and renal replacement therapy, hemodynamic instability with no alternative etiology, and hematemesis score two points each. The absence of external bleeding was scored a negative point. Lee et al[7] in their retrospective study of 105 patients who underwent bedside EGD for upper GI bleeding, found approximately 30% of patients had bleeding ulcers, 26% had nonbleeding ulcers, and 23% had stress-related mucosal changes[7]. Varices and malignancy were identified in 5 and 4%, respectively.

Stress ulcers are common in critical care settings, up to 3% from prior literature. Acute illness and inflammation can alter splanchnic circulation and mucosal protection, making GI mucosa vulnerable to ulceration and resultant bleeding[8]. Shock and hemodynamic instability, mechanical ventilation, and renal failure further increase the risk of GI bleeding in ICU patients[9]. Additionally, critically ill patients have underlying ailments requiring the use of corticosteroids, anticoagulants, and antiplatelets (AP) agents. This polypharmacy further increases the risk of bleeding. Coagulopathy and the use of mechanical ventilation have also been identified as risk factors for GI bleeding[10]. Endoscopy is the standard of treatment for acute GI bleeding unresponsive to proton pump inhibitors and conservative management. Endoscopy is recommended within 24 hours of the bleeding episode and could provide direct visualization of the bleeding vessel for ligation. Repeat endoscopic ligation or embolization may be needed for repeated bleeding episodes[11]. Optimal timing of endoscopy is essential in critically ill patients[12].

On colonoscopy, the commonest causes were colitis, ulcers, and diverticular bleeding. Cremone et al[2] state the most common diagnoses besides colonoscopy in ICU were diverticular bleeding, ischemic colitis, tumor lesion, and angiodysplasia[2]. Kim et al[13] state ischemic colitis, rectal ulcer, and hemorrhoids as primary diagnoses in 28 patients through bedside colonoscopy[13]. Lin et al[14] describe fifty-five patients admitted for lower GI bleeding[14]. Colitis and rectal ulcers were the most frequent causes of lower GI bleeding in 24/55 patients. A retrospective study on 253 patients who underwent EGD or colonoscopy for GI bleeding in the ICU described Peptic ulcer disease and mucosal lesions as the most common cause of bleeding on EGD[12]. Ischemic colitis and rectal ulcers were the common diagnoses in the colonoscopy group[15].

Critically ill patients are highly susceptible to adynamic/dynamic bowel obstruction due to poor gut motility. Multiple causes can contribute to ileus in the critical care setting: Electrolyte abnormalities, polypharmacy with drugs that decrease gut motility, and prolonged patient immobilization[16]. Small bowel ileus is often managed conservatively with lactulose and polyethylene glycol solutions. In large bowel ileus, especially colonic pseudo-obstruction, neostigmine can be tried. However, endoscopic decompression is often required when the dilation diameter reaches a critical point (cecum diameter > 12 cm) and heralds a risk of rupture[17,18]. Endoscopy carries an inherent risk of perforation in such cases, but subsequent decompression and rectal tube placement improves prognosis. Percutaneous cecostomy or surgery may be needed in severe emergent cases. Prolonged placement of rectal tubes should be avoided as it is associated with an increased risk of perforation. In patients with low-grade bowel obstruction, temporary rectal tube placement for decompression collaboration with surgery for resection may be necessary.

The third most common indication for endoscopy in the critical care setting is volvulus, especially sigmoid volvulus[19]. It is common in elderly patients and is associated with the presence of a hyper-mobile sigmoid colon with one or more redundant sections and a narrow mesenteric base. Constipation, diabetes, previous abdominal surgery, prolonged immobilization and neuro-psychiatric conditions have also been identified as risk factors[20]. If not promptly treated, sigmoid volvulus can lead to necrosis and perforation. Volvulus with intact blood supply requires urgent colonoscopic detorsion to preserve the bowel. However, due to the increased risk of recurrence, elective surgical removal of redundant bowel segments is often required[21].

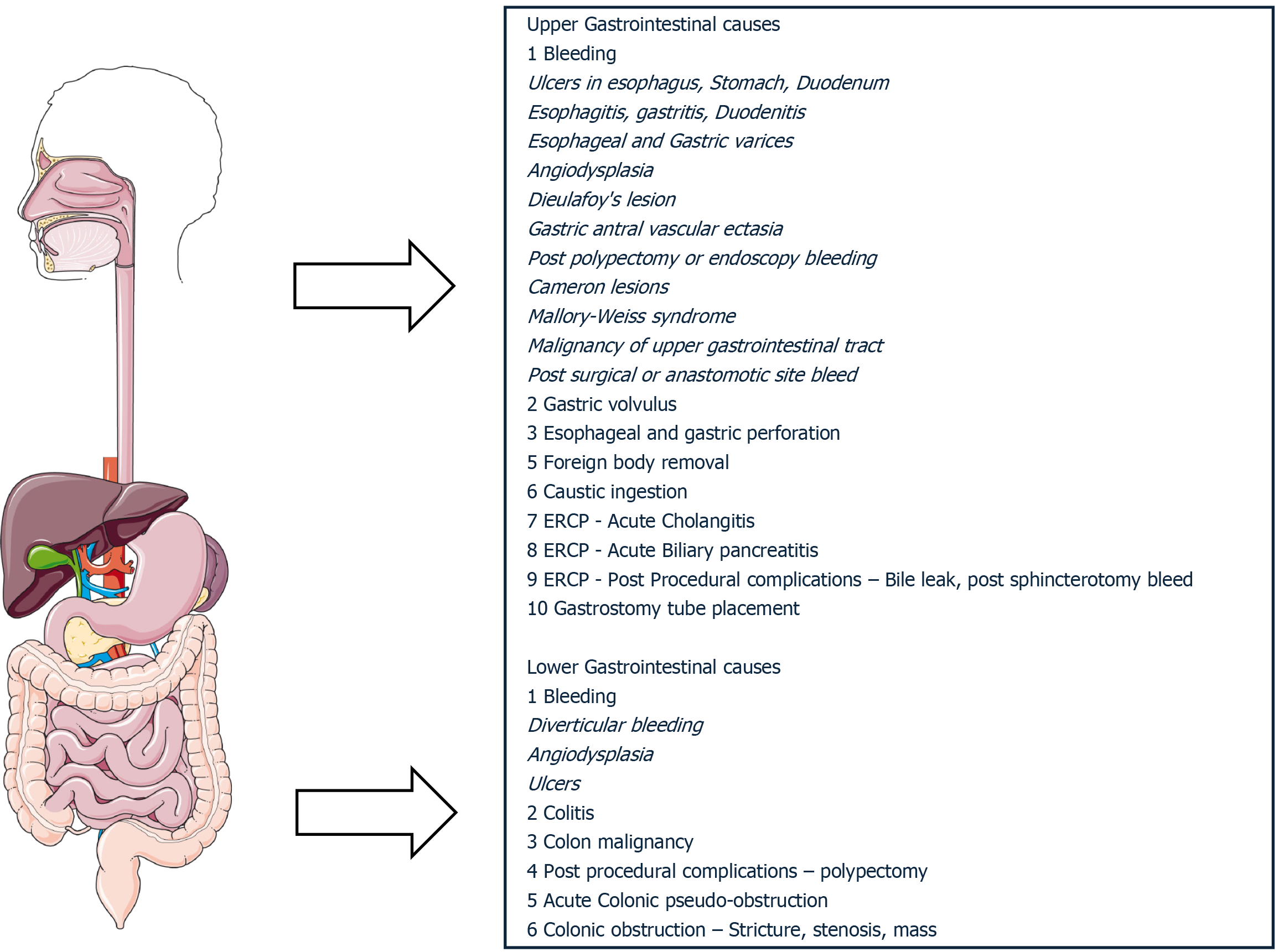

Percutaneous gastrostomy tubes can be placed in the ICU for patients requiring long-term nutritional support that cannot be transported to the endoscopy unit due to multiorgan dysfunction[22]. Figure 1 shows the common indications for performing endoscopy in the ICU.

Figure 1 Common encountered gastrointestinal emergencies requiring endoscopy in critically ill patients.

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography.

Bedside endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) may be necessary for hemodynamically unstable patients with Acute cholangitis[23]. Complications such as post-ERCP pancreatitis need preventative measures perioperatively to decrease complication risk. Saleem et al[24] describe a retrospective study on ERCPs performed in the ICU for unstable patients who could not be transported to the endoscopy unit[24]. The authors describe biliary sepsis, gallstone pancreatitis, choledocholithiasis, and cholangitis as indications for ERCP in the ICU. The procedure is often safe; however, patients often have high 30-day mortality due to underlying multiorgan dysfunction.

The literature provides evidence of bedside endoscopic ultrasound in critically ill patients for choledocholithiasis, Cholecystitis, mediastinal abscess, pancreatic abscess, and pancreatic pseudocyst. It additionally allows for therapeutic interventions, including transmural drainage[25].

CONSIDERATIONS OF GI ENDOSCOPY IN THE ICU

It is often not feasible to take ICU patients to the operative room for most procedures due to concerns of decompensation during transport or interruption in critical care. Technological advancements, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness have made bedside procedures more common these days. However, bedside procedures carry inherent risks and an inability to escalate care in case of complications. Bedside procedures often have drawbacks, such as a lack of space and fewer available personnel and tools. Operating rooms are better equipped with necessary equipment, have better sterility, and better care escalation measures, i.e., in case of bleeding during endoscopic procedures, open laparotomy can be performed if needed[26].

Coagulopathy and bleeding risk

Elevated bilirubin and creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, and longer hospital length of stay were predictive of new-onset GI bleeding in critically ill[27]. Krag et al[28] state coexisting diseases including liver failure, coagulopathy, and organ failure as risk factors for GI bleeding in his study of 1034 ICU patients from 97 ICUs[28]. The presence of H pylori and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were also a risk factor for GI bleeding in the ICU[29,30]. In patients in the ICU with thrombocytopenia, diagnostic colonoscopies can be performed if the platelet count is greater than 20000/mL. In patients requiring biopsies, platelets have to be greater than 50000/mL[31]. American College of Gastroenterology guideline recommends blood transfusion for Hemoglobin < 7 g/dL in hospitalized hemodynamically stable patients, including critically ill patients[11]. Studies have not shown the benefit of a liberal transfusion strategy in the ICU. Often, patients in the ICU are on anticoagulation (AC) or AP for various reasons, including atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, and hypercoagulable states. Discontinuation is often associated with increased risk and is not possible for patients taken for emergent procedures. Endoscopic procedures and interventions are often associated with a higher risk of bleeding in patients on AP and AC. Employing a dual modality of interventions such as epinephrine, hemostatic clip, coagulation, and cauterization for hemostatic control can ensure a decreased risk of bleeding. A low threshold for bleeding interventions should be followed during endoscopy in such patients. Correction of platelet and hemoglobin can ensure a decreased risk of complications. Second look endoscopy in patients with Peptic ulcer disease bleeding patients does not improve mortality, need for interventions or blood transfusions[32].

Bowel preparation and impaired mucosal visualization

Good bowel preparation is essential for complete colon visualization and identifying the source of bleeding. Poor bowel preparation increases the rate of complications. Kim et al[13] conducted a study on 253 patients who underwent EGD or colonoscopy for GI bleeding in the ICU and concluded that early EGD helps identify the bleeding focus and endoscopic hemostasis[12]. However, the authors state early colon in a patient with poor bowel prep and the presence of blood made identifying the site of bleeding difficult. Church et al[1] also described poor prep in 15 of 49 bedside colonoscopies in ICU patients, making it necessary to abort the procedure[1]. Therefore, bowel preparation is necessary before colonoscopy to better identify the source of bleeding. Tap water enema or Polyethylene glycol solutions can be utilized. Tap water enemas are often beneficial if the source of pathology is suspected to be in the rectal area. Ablation techniques used for the management of vascular ectasia can be associated with perforation and bleeding in the immediate period. Argon photocoagulation of colon, when performed in a poor bowel preparation patient, particularly those in the ICU urgent colonoscopy, can be associated with colonic explosion leading to perforation and emergent surgery. Therefore, attempting to optimize the bowel cleansing is necessary to avoid complications[31]. Duboc et al[33] state colonoscopes in the ICU are more successful for indications other than lower GI bleed[33]. One factor may be poor preparation, making visualization of the bleed site difficult. However, bowel cleansing is not always successful in patients with bowel obstruction of the bowel from mass or stricture. However, decompression can be successful with suboptimal preparation, unlike identifying the source of bleeding. Duboc et al[33] also states that 50% of the patients who underwent bedside colonoscopy also needed an additional investigation, such as a contrast-enhanced computed tomography, to identify the source of bleeding[33].

Impaired mucosal visualization from poor preparation can increase the risk of perforation. CO2 insufflation instead of air can decrease air retention in the colon and risk of perforation. Utilizing water jet instead of air for visualization of the colon in poor preparation and bowel obstruction decreases further distension and risk of perforation. Post-procedural observation for abdominal distension, chest pain, dyspnea, emphysema, and fever may be necessary. Multidisciplinary care and collaboration with surgery, if necessary, in emergencies, can decrease mortality.

Outcomes in ICU

Cremone et al[2] state septic shock, heart transplantation, multiorgan failure, and ischemic colitis as significant factors for death within one month after an emergency colonoscopy[2]. Kim et al[13] in their study of 28 ICU patients who underwent bedside colonoscopy, stated endoscopic hemostasis was achieved in 39% of patients on colonoscopy[13]. Lin et al[14] describe fifty-five patients admitted for lower GI bleeding and state endoscopic hemostasis was achieved in 30% of patients[14]. Patients, however, had a > 50% in hospital mortality due to underlying comorbidities.

Lee et al[7] in their retrospective study of 105 patients who underwent bedside EGD for upper GI bleeding, found state endoscopic hemostasis was achieved in 68% of bleeding ulcers; however, the rebleeding rate was 30%[7]. The mortality rate in the hospital was 77% for these patients, a high rate as in prior studies due to underlying multiorgan failure. Church et al[1] also describe 36% mortality in forty-nine bedside colonoscopies in ICU patients from multiorgan failure[1].

Anesthesiology and sedation challenges

Non-operating room anesthesia is a spectrum of anesthesia cases outside the traditional operating room[34]. It includes Anesthesia in locations with a lack of a controlled environment presents in an operating room. Critically ill patients in the ICU often have multiple comorbidities and may be hemodynamically unstable. Critically ill patients have an increased susceptibility to anesthetic side effects due to multiorgan dysfunction. Anesthetics can also cause hemodynamic instability and arrhythmias[16]. ICU patients need extensive respiratory and hemodynamic support due to limited physiologic reserve to maintain organ function and oxygenation. This can further worsen mucosal ischemia and increase the risk of GI bleeding. Anesthesia increases these support needs due to its inherent depressive properties on the cardio-pulmonary system[17,18]. Thus, transient hypoxemia or hypercarbia may be poorly tolerated in these patients and can lead to cardiovascular collapse. Thus, care must be taken to properly titrate the analgesic and cardiopulmonary effects of anesthesia in critically ill patients. Care of intubated and tracheostomy patients that are on ventilation to prevent accidental extubation during the procedure and careful drug dosing to avoids errors since patients are on multiple medications.

Further logistics and ergonomics in regard to space in ICU for endoscopy equipment and personnel. Often Total Intravenous anesthesia is the most common anesthetic technique used in the ICU. Communication with the ICU team, including nurses, respiratory therapists, and intensivists before procedure setup, can help with smooth procedures. The choice of sedation or anesthesia depends on patient comorbidities and procedure. Patients in the ICU are often American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status IV and V and are at high perioperative risks and complications. Dedicated trained anesthesiologist for the procedure and for managing any adverse events peri procedurally. Patient factors including Sepsis, Shock, Arrhythmias, Cardiac Failure, Hemodynamic instability, Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Renal failure, Delirium, Bleeding, Electrolyte abnormalities, Ventilation status, Vascular access are some challenges faced by anesthesiologists in the ICU. Discussing advance directives with family and patients prior to procedure to have clarity prior to procedure[35].

Familiarization with local ICU practices can help with successful procedures in the ICU. Metzner et al[36] in their study on analyzing the anesthesia closed claims database, state anesthesia in remote locations have an increased risk of oversedation and inadequate respiratory management[36]. This is due to inadequate workspace, lack of support staff, and unfamiliar equipment and practices.

Multidisciplinary collaboration in the ICU

Gastroenterologists, Intensivists, Anesthesiologists, and Surgeons involved in decision-making the best care for patients often lead to improved outcomes. Aspects of bowel preparation, anticoagulation, hemodynamic instability, and Patient and family consent should be discussed between gastroenterologists and the critical care team. Involvement of surgeons prior to endoscopy procedure for patients with colitis, risk of perforation, bowel obstruction, volvulus ensures quicker care in emergent situations on unsuccessful endoscopy.