Copyright

©The Author(s) 2016.

World J Crit Care Med. Feb 4, 2016; 5(1): 17-26

Published online Feb 4, 2016. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v5.i1.17

Published online Feb 4, 2016. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v5.i1.17

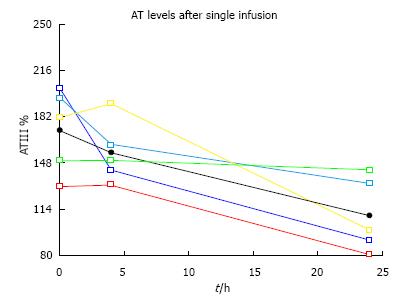

Figure 1 AT levels after calculations for bolus single infusions to attain > 175% plasma antithrombin levels (personal file AKV).

AT: Antithrombin.

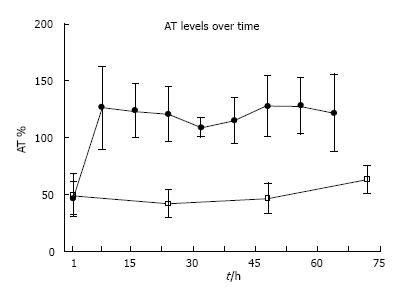

Figure 2 A 72 h depiction of q 8 h dosage coefficient of variations for the antithrombin-treated burn patients (black dots) compared to control plasma antithrombin levels (white squares) (personal file AKV).

AT: Antithrombin.

Figure 3 The severity of injury requiring an escharotomy in a burn patient with 80% total body surface area (personal file AKV).

Figure 4 The “peeling off” of the eschar, not requiring knife excision with exposed viable subcutaneous tissue and minimal bleeding (personal file AKV).

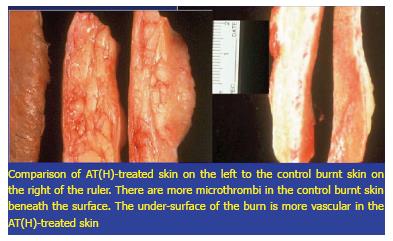

Figure 5 A representation of the pathology in third degree burnt skin from a patient treated with plasma-derived antithrombin and in patient without plasma-derived antithrombin treatment.

Whereas the skin beneath the control eschar is dead and non-viable with clotted and coagulated blood vessels, the skin and subcutaneous tissue beneath the phAT-treated skin is more viable in comparison with fewer thrombi (personal file AKV). phAT: Plasma-derived antithrombin.

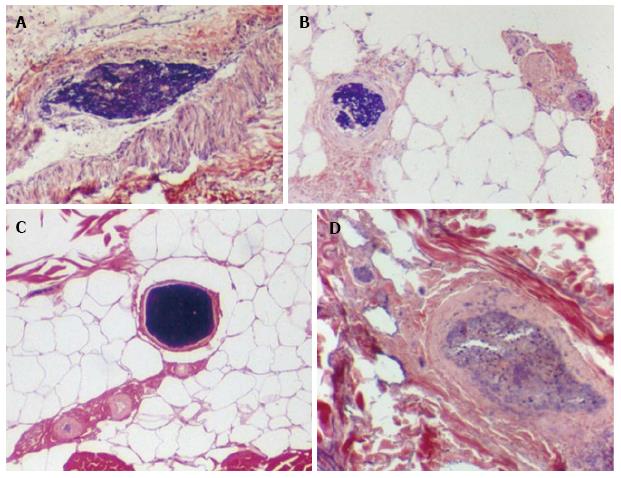

Figure 6 The thrombi, sludge and necrotic debris in burnt skin subcutaneous tissue blood vessels.

A: Illustrates a blood vessel with sludge and fibrin debris; B: Depicts a small vessel with fibrin debris; C: Shows a clotted vessel; D: A larger vessel occluded with amorphous material. Magnification 40-100 ×, PTAH staining (personal file AKV).

- Citation: Kowal-Vern A, Orkin BA. Antithrombin in the treatment of burn trauma. World J Crit Care Med 2016; 5(1): 17-26

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3141/full/v5/i1/17.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v5.i1.17