Published online Nov 28, 2015. doi: 10.5412/wjsp.v5.i3.229

Peer-review started: May 21, 2015

First decision: June 18, 2015

Revised: July 1, 2015

Accepted: September 7, 2015

Article in press: September 8, 2015

Published online: November 28, 2015

Processing time: 188 Days and 19.4 Hours

Controversial pigmented lesions in children are a problem for pathologist, clinicians and families that are confronted with this dilemma. Some skin lesions in this population defy diagnosis with pathologists split between a benign diagnosis and a cancer diagnosis. Three cases of controversial pigmented lesions in the pediatric population are presented. Three patients underwent radical resection of the controversial pigmented lesion, intra-operative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy. Due to the low morbidity of the SLN procedure a case is made to perform lymphatic mapping in this clinical scenario. If the SLNs are negative, not much is lost except for the scar and this becomes another line of evidence that perhaps the original lesion was benign. If the SLN shows metastatic cells, then the original skin lesion must be malignant and the patient is offered stage III recommendations that would include complete node dissections and adjuvant Interferon therapy. This strategy provides for adequate treatment of the worse-case scenario, that the skin lesion is malignant. The cost to the patient is a low morbidity procedure, the SLN biopsy.

Core tip: The sentinel lymph node staging procedure can be used to treat effectively pediatric patients with ambiguous pigmented skin lesions.

- Citation: Psaltis J, Reintgen E, Antar A, Giori M, Alvin L, Benjamin A, Budny B, Gianangelo T, Gruman A, Stamas A, Reintgen M, Giuliano R, Smith J, Reintgen D. Malignant melanoma in the pediatric population. World J Surg Proced 2015; 5(3): 229-234

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2832/full/v5/i3/229.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5412/wjsp.v5.i3.229

Malignant melanomas are remarkably rare in children. Roughly 2% of melanomas occur in children under the age of 20 and approximately 0.4% of cases occur in prepubescent children[1]. In the United States, childhood and adolescent melanoma accounts for only 1.3% of all cases of melanoma[2]. Nevertheless, malignant melanoma (MM) is a potentially fatal disease, and it is critical to consider MM as a differential diagnosis of any pigmented lesion in a child. Clinically, childhood melanoma presents similarly to adult melanoma, and the use of the asymmetry, borders, color, diameter, and evolution of early diagnosis criteria can be used to screen children as well[3]. It has been shown that children diagnosed with melanoma have the same prognostic outcomes as their adult counterparts, while those diagnosed with melanoma before the age of 10 have a better outcome than those diagnosed between the ages of 10 and 20[3].

Nevi can be a common finding amongst children. Depending on the size of the lesion, a congenital melanocytic nevus is one of the risk factors for developing childhood melanoma due to the potential malignant transformation[4]. In dealing with pigmented lesions in this population of particular concern is the Spitz nevus, a benign lesion with morphological features similar to malignant melanoma, first described by Sophie Spitz in 1948[5-9]. Spitz stated that although this type of nevus was histologically malignant, it behaved in a benign manner[10]. As such, one of the biggest difficulties in diagnosing melanoma in children is differentiating a malignant melanoma from a benign Spitz Nevus[7,8]. Such lesions of uncertain biological potential are termed atypical spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms[7]. One study demonstrated that even amongst an experienced panel of pathologists, the variability in diagnosis was still substantial[9]. The differential diagnosis between a melanoma and a dysplastic Spitz nevus was still confusing, with the most common error being an interpretation of a benign lesion when it was actually malignant[11]. In addition pathologists are wary of saddling a child with a malignant diagnosis if indeed the skin lesion behaves in a benign fashion. Under-diagnosing or over-diagnosing controversial pigmented lesions in the pediatric population have repercussions either way. If under-diagnosed, the patient may not receive the standard definitive cancer treatment, such as a radical resection and a sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy. Although somewhat controversial, this primary treatment has been associated with a survival benefit in adults if indeed the SLN is found to contain metastatic disease. By under-treating children with MM, life-saving treatment may be denied[4,12-15]. If over-diagnosed, the patient may have procedures that are not necessary, resulting in increased morbidity. In addition the children are then labeled with a cancer diagnosis for the remainder of their lives. Patients mistakenly diagnosed with melanoma may exhibit fear of relapse and may not be able to obtain life or health insurance[14].

The misdiagnosis of melanoma is the second most common reason for cancer malpractice claims in the United States, second only to mistakes in breast cancer diagnosis[16]. All these claims are involved in the under-diagnosis of melanoma and physicians have always been willing to practice defensive medicine, despite increasing the costs of care, to guard against under-diagnosis and less than standard treatment.

In this report we describe three patients with controversial pigmented lesions in the pediatric population. The reports have complete pathology that helps to define the difficulty of the diagnosis, and the full spectrum of issues that arise in dealing with atypical pigmented skin lesions in this population is illustrated. A case is made for lymphatic mapping and SLN biopsy in this setting since the procedure exhibits low morbidity and finding metastatic cells in the SLN can help with the primary diagnosis. Finally a “standard of care” treatment is given for the metastatic disease.

A previously healthy 2-year-old girl presented to outside physicians with an irregular mole on her right calf. A biopsy was performed and pathology showed an atypical nevus (Spitz nevus) vs melanoma. The patient underwent a radical resection of the primary melanoma and SLN biopsy. Pathology showed a 4.1 mm melanoma with clear margins at the primary site. However 2/3 right groin SLNs were positive for metastatic melanoma. The patient underwent a complete lymph node dissection (CLND) of her right groin and all further nodes were negative. The patient was referred to St. Jude’s Children Hospital where she received 1 year of adjuvant Interferon therapy.

This case involves an otherwise healthy 4-year-old white male who presented with a solid mass in his pinna of the right ear that appeared mostly subcutaneous. It had increased in size and became painful and irritating to the patient.

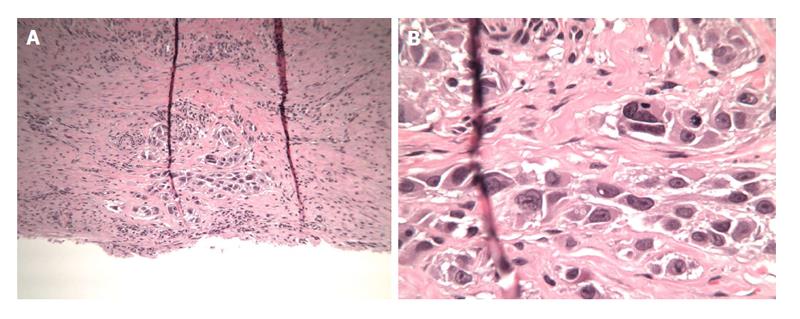

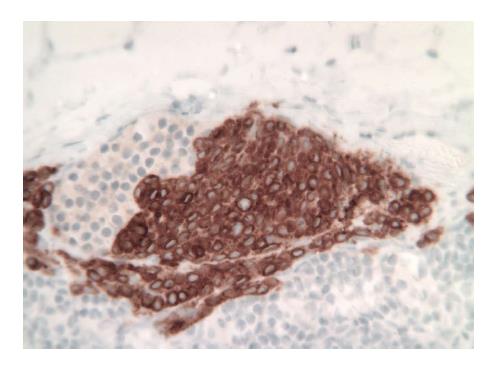

The patient underwent an excisional biopsy of the mass and pathology revealed features of an intradermal Spitz nevus, with low mitotic rate, nuclear atypia and incomplete maturation of melanocytes at the base of the lesion. Local pathology showed an atypical nevus with the proliferation of large melanocytes. The lesion was positive for Melan-A and S-100 and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, desmin, ESA, GFAP, muscle specific actin and Ki-67. Ki-67 stain was positive and showed increased proliferative activity in the tumor cells. The case was then sent for consultation with the Mayo Clinic, which reported a non-ulcerated malignant spitzoid melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 3.6 mm. The lesion was analyzed at UCSF and pathology was interpreted as an atypical compound proliferation of spitzoid melanocytes consistent with a spitzoid melanoma. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of the tumor demonstrated gain in chromosomes 6p, 11q and 8q. These molecular findings favor interpretation as a spitzoid melanoma. Immunostaining for p16 demonstrated relative prominent positivity to verify no loss in chromosome 9p.

The patient was taken to the OR where, under general anesthesia, he underwent a radical resection of the melanoma of the right ear (wedge resection), intra-operative lymphatic mapping and SLN biopsy (Figures 1 and 2). Histologic examination revealed the SLNs to be negative for any evidence of metastatic disease. The wedge resection of the ear showed a nest of malignant appearing melanocytes deep within the dermis (Figure 3) and margins were free. The final diagnosis was residual malignant spitzoid melanoma with clear margins and negative SLNs.

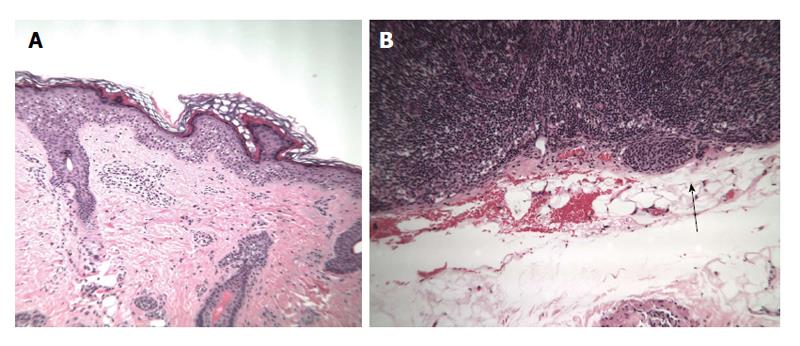

A previously healthy 12-year-old girl presented to her local dermatologist with an atypical nevus on her left forearm. A biopsy was performed that had the differential diagnosis of a dysplastic nevus vs melanoma (Figure 4A). The patient was treated under the melanoma protocol at USF with a radical resection of the primary site, intra-operative lymphatic mapping and SLN biopsy. Pathology showed clear margins from the primary site but the SLN was initially diagnosed as positive for micrometastatic disease (Figure 4B). A second opinion on the pathology showed a dysplastic nevus and benign nevus cells in the SLN (Figure 5). The patient is being observed.

The melanoma database at the University of South Florida (USF) and Florida Hospital - North Pinellas is a prospective database that is used for day-to-day clinical care and for clinical research. Under a USF IRB approval, all patients registered in the database are consented to have their data de-identified and used in future research projects. Case reports at USF do not require IRB approval.

Despite such difficulties in diagnosing malignant melanoma, it is important to avoid a delay in the diagnosis because early detection and aggressive treatment improves the patient’ chances of survival[6,10,12]. The recommended course of action after detection and diagnosis of malignant melanoma is a radical resection of the primary site and if the melanoma is greater than 0.76 mm in thickness, a SLN biopsy. Complete lymph node dissections are reserved for those patients with a positive SLN[6-10]. The nosologic category of childhood spitzoid melanoma refers to an emerging entity that seems distinct from conventional adult melanoma. Such tumors often lack BRAF mutations and are reported in the past literature under such flawed designations as malignant Spitz nevus. Findings to date suggest a small risk for metastases to regional lymph nodes with a low risk for widespread dissemination. It is thought that such lesions represent a low-grade form of melanoma[14]. Immunohistochemical differentiation with S-100 protein and HMB-45, although useful in identifying melanocytic cells, is not useful in distinguishing between malignant melanoma and Spitz Nevi, as both lesions stain positive with both markers[6,17]. A newer diagnostic assay using 5 markers (ARPC2, FN1, RGS1, SPP1 and WNT2) has been shown to be effective in differentiating between malignant melanoma and Spitz nevi[17]. Using an algorithm based on the pattern and intensity of these 5 markers with varying skin lesions, this multi-marker assay was able to correctly diagnose a high percentage of melanomas, Spitz nevi, dysplastic nevi, and other misdiagnosed lesions[17]. The multi-marker assay corrected three-quarters of cases in which incorrect pathological diagnosis were rendered, including melanomas initially diagnosed as nevi[17]. The test could be used to aid in the histologic diagnosis of melanoma, preventing errors in under diagnosis[17]. Regardless, it still remains difficult for clinicians and pathologists to differentiate between the two diagnoses (benign vs malignant), even for those who deal with such cases on a daily basis.

Performing a SLN biopsy after a wide local excision of the lesion can serve both a diagnostic and therapeutic purpose. Histopathological examination of the harvested SLNs can be used to support the diagnosis of the lesion as benign, helping to avoid incorrectly burdening a young patient with a lifelong diagnosis of malignancy as well as decrease the morbidity from subsequent and more invasive procedures such as a CLND. However, if the pathology reveals that the lesion is malignant, then the nodes can still serve a further diagnostic purpose by allowing clinicians to better stage and grade the harmful lesion, and determine if further surgery is indicated. In addition to these diagnostic benefits, the removal of the SLN can serve a therapeutic purpose by removing all disease, since in all stage III patients (regional nodal disease), the metastatic disease is confined to the SLN 85% of the time. That is, the SLN acts as an effective trap in the regional basin to spread of the metastatic disease to higher non-SLNs[18].

Although controversy exists on whether performing the SLN procedure provides a survival benefit to the patient, we know that the best evidence of efficacy for the SLN procedure is displayed in those patients with documented stage III disease, and a positive SLN[12-15].

Controversial pigmented lesions in children refer to the fact that some skin lesions in this population are problematic in trying to determine a benign pathology from a malignant. Many times multiple pathologists will render an opinion on the skin biopsy with some basing their benign reading on the prognosis for a Spitz nevus quoted in the literature for patients even though the cytology of the cells are malignant. Other pathologists prefer to interpret the skin histology based on what they observe with their microscopic examination. Newer genetic profiling of these skin lesions may be helpful in differentiating these lesions into appropriate benign vs malignant categories. However, clinicians are left with little guidance in trying to care for patients with this clinical scenario.

For the last 10 years the Cutaneous Oncology Program at USF/FH-N Pinellas has implemented a protocol for dealing with these difficult cases. Since the lymphatic mapping and SLN procedure is a low morbidity procedure, pediatric patients with controversial pigmented lesions are treated as if they carry the melanoma diagnosis, and are considered candidates for a radical resection of the primary melanoma to obtain clear margins and SLN biopsy for nodal staging. This protocol can accomplish the following: (1) If the SLN is negative for metastases, then that data would be considered a line of evidence that the skin lesion is benign and the patient has a good prognosis; (2) If the SLN is positive for metastases, this is a good indication that the original skin lesion is malignant making the patient eligible for CLNDs and adjuvant Interferon therapy. Case 3 illustrates the fact that benign nevus cell rests in the SLN must be differentiated from metastatic melanoma cells in the SLN; and (3) Patients will not be under treated if indeed they have the malignant phenotype. Likewise any over treatment of the patients is associated with a low morbidity operation, the SLN biopsy.

Even though malignant melanoma diagnoses in children are rare, we must be cognizant of such a possibility because early diagnosis is crucial to patient outcome. Despite new methods used to distinguish nevi and melanoma from each other, a certain protocol system, such as that implemented at the Cutaneous Oncology Program at USF/FH-N Pinellas, is crucial in assuring the appropriate patient treatment.

As recurrences and melanoma-related death inevitably remain a possibility years after patient diagnosis, it is necessary for long-term patient follow-up, including full-body skin examination in this population for the remainder of their lives[3,19].

Pediatric patients with controversial pigmented skin lesions are problematic in treatment and for assigning prognosis.

Three patients are described with skin lesions where the histologic diagnosis of benign or malignant is in doubt.

The differential diagnosis is between a benign dysplastic nevus and a malignant melanoma.

Histologic examination using routine hematoxolin and eosin stain and immunohistochemistry with S-100 and HMB-45 stains was performed.

Pre-operative lymphoscintigraphy was performed to identify all nodal basins at risk for metastases.

The primary site differential was between dysplastic nevi vs malignant melanoma. The differential diagnosis in the sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) was metastatic melanoma vs benign nevus cells.

All 3 patients underwent radical resection of their primary sites and SLN biopsy. The patient with a positive SLN was administered adjuvant Interferon alfa-2b for 1 year.

The SLNs are all nodes in the regional basin that have a direct connection by way of afferent lymphatics to the primary melanoma site. SLNs are identified with either a blue dye or radiocolloid mapping technique.

Since the lymphatic mapping and SLN procedure is a low morbidity procedure, pediatric patients with controversial pigmented lesions are treated as if they carry the melanoma diagnosis, and are considered candidates for a radical resection of the primary melanoma to obtain clear margins and SLN biopsy for nodal staging.

This article includes valuable information regarding the complexities of distinguishing benign nevi from malignant melanoma in the pediatric population.

P- Reviewer: Mocellin S, de la Serna IL S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Boddie AW, Smith JL, McBride CM. Malignant melanoma in children and young adults: effect of diagnostic criteria on staging and end results. South Med J. 1978;71:1074-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hamre MR, Chuba P, Bakhshi S, Thomas R, Severson RK. Cutaneous melanoma in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;19:309-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ferrari A, Bono A, Baldi M, Collini P, Casanova M, Pennacchioli E, Terenziani M, Marcon I, Santinami M, Bartoli C. Does melanoma behave differently in younger children than in adults? A retrospective study of 33 cases of childhood melanoma from a single institution. Pediatrics. 2005;115:649-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van der Ploeg AP, Haydu LE, Spillane AJ, Quinn MJ, Saw RP, Shannon KF, Stretch JR, Uren RF, Scolyer RA, Thompson JF. Outcome following sentinel node biopsy plus wide local excision versus wide local excision only for primary cutaneous melanoma: analysis of 5840 patients treated at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2014;260:149-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Spitz S. Melanomas of childhood. Am J Pathol. 1948;24:591-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Reintgen DS, Vollmer R, Seigler HF. Juvenile malignant melanoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;168:249-253. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ghazi B, Carlson GW, Murray DR, Gow KW, Page A, Durham M, Kooby DA, Parker D, Rapkin L, Lawson DH. Utility of lymph node assessment for atypical spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2471-2475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Murali R, Sharma RN, Thompson JF, Stretch JR, Lee CS, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in histologically ambiguous melanocytic tumors with spitzoid features (so-called atypical spitzoid tumors). Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:302-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Allen AC, Spitz S. Histogenesis and clinicopathologic correlation of nevi and malignant melanomas; current status. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;69:150-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ceballos PI, Ruiz-Maldonado R, Mihm MC. Melanoma in children. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:656-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Barnhill RL, Argenyi ZB, From L, Glass LF, Maize JC, Mihm MC, Rabkin MS, Ronan SG, White WL, Piepkorn M. Atypical Spitz nevi/tumors: lack of consensus for diagnosis, discrimination from melanoma, and prediction of outcome. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:513-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Mozzillo N, Nieweg OE, Roses DF, Hoekstra HJ, Karakousis CP, Puleo CA, Coventry BJ. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:599-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1104] [Cited by in RCA: 1061] [Article Influence: 96.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Coit D. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: a plea to let the data speak. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3359-3361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Thompson JF, Faries MB, Cochran AJ. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: a plea to let the data be heard. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3362-3364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kachare SD, Brinkley J, Wong JH, Vohra NA, Zervos EE, Fitzgerald TL. The influence of sentinel lymph node biopsy on survival for intermediate-thickness melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3377-3385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Palazzo JP, Duray PH. Congenital agminated Spitz nevi: immunoreactivity with a melanoma-associated monoclonal antibody. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:166-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kashani-Sabet M, Rangel J, Torabian S, Nosrati M, Simko J, Jablons DM, Moore DH, Haqq C, Miller JR, Sagebiel RW. A multi-marker assay to distinguish malignant melanomas from benign nevi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6268-6272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Reintgen C, Reintgen M, Reintgen D. Evidence for a Better Nodal Staging System for Cancers. The Importance of Non-Sentinel Lymph Node Metastases. 2014;. |

| 19. | Larsen AK, Jensen MB, Krag C. Long-term Survival after Metastatic Childhood Melanoma. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2:e163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |