Published online Mar 28, 2015. doi: 10.5412/wjsp.v5.i1.167

Peer-review started: August 6, 2014

First decision: August 28, 2014

Revised: September 13, 2014

Accepted: February 9, 2015

Article in press: February 11, 2015

Published online: March 28, 2015

Processing time: 239 Days and 23.4 Hours

AIM: To appraise the current evidence for prophylactic oophorectomy in patients undergoing primary curative colorectal cancer resection.

METHODS: Occult ovarian metastases may lead to increased mortality, therefore prophylactic oophorectomy may be considered for women undergoing colorectal resection. A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed for English language studies from 1994 to 2014 (PROSPERO Registry number: CRD42014009340), comparing outcomes following prophylactic oophorectomy (no known ovarian or other metastatic disease at time of surgery) vs no ovarian surgery, synchronous with colorectal resection for malignancy. Outcomes assessed: local recurrence, 5-year mortality, immediate post-operative morbidity and mortality, and rate of distant metastases.

RESULTS: Final analysis included 4 studies from the United States, Europe and China, which included 627 patients (210 prophylactic oophorectomy and 417 non-oophorectomy). There was one randomized controlled trials, the remainder being non-randomised cohort studies. The studies were all at high risk of bias according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s assessment tool for randomised studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa Score for the cohort studies. The mean age of patients amongst the studies ranged from 56.5 to 67 years. There were no significant differences between the patients having prophylactic oophorectomy at time of primary colorectal resection compared with patients who did not with respect to local recurrence, 5-year survival and distant metastases. There was no difference in post-operative complications or immediate post-operative mortality between the groups.

CONCLUSION: Current evidence does not favour prophylactic oophorectomy for patients without known genetic predisposition. Prophylactic surgery is not associated with additional risk of post-operative complications or death.

Core tip: Prophylactic oophorectomy is a potentially attractive additional procedure that can be performed at the time of primary colorectal resection, to reduce the risk of ovarian metastasis and de novo ovarian malignancy later in a female patient’s clinical course. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the available literature reveals that, though this procedure can be performed with little additional morbidity or mortality risk at the time of surgery, it confers no long term survival benefit, and carries a significant side effect profile.

- Citation: Thompson CV, Naumann DN, Kelly M, Karandikar S, McArthur DR. Prophylactic oophorectomy during primary colorectal cancer resection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Proced 2015; 5(1): 167-172

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2832/full/v5/i1/167.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5412/wjsp.v5.i1.167

Women who have colorectal cancer are at a higher risk of developing primary gynaecological tumours, particularly when aged less than 50[1,2], and there is a relatively high rate of ovarian metastases amongst pre-menopausal women with colorectal cancer[3,4]. Furthermore, patients who have colorectal metastases to the ovary have a poor prognosis and respond poorly to chemotherapy[5]. Although the route of spread is mostly unknown, haematogenous, lymphatic and transcoelomic routes of dissemination have all been proposed[6,7]. Prophylactic ovarian surgery has been advocated for women with hereditary syndromes such as Lynch syndrome and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)[8,9]. However, prophylactic surgery for women with no known genetic risk factors is more controversial[10]. Prophylactic oophorectomy in these patients would be aimed at preventing the subsequent development of primary ovarian malignancy, or improving the local recurrence rate following colorectal cancer resection by removing occult synchronous or future metachronous metastases. The authors hypothesized that prophylactic oophorectomy would result in a reduction of local recurrence rate and mortality.

Surgeons undertaking primary curative colorectal cancer have ready access to the pelvis and therefore are ideally placed to perform the relatively straightforward procedure of oophorectomy if such surgery was considered appropriate. Concurrent oophorectomy therefore has the theoretical potential to utilize the same surgical approach (laparoscopic or open), and have similar wound-associated morbidity. Justification for prophylactic oophorectomy in these circumstances must be made on the basis of evidence of safety, improved outcomes in terms of local recurrence rate and survival of patients with colorectal cancer, and patient preference. The authors aimed to examine the current peer-reviewed literature in order to determine whether evidence in the last 20 years justifies prophylactic surgery.

A systematic review was performed according to a pre-specified protocol registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registry number CRD42014009340). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, OVID SP, and PubMed versions of MEDLINE were searched for published articles comparing outcomes following prophylactic oophorectomy at the time of primary colorectal cancer resection with patients without prophylactic surgery. Only studies published after 1994 were included in order to capture a 20-year period to date of investigation. This systematic search was performed independently by two investigators. Search terms were use to search MEDLINE, including “prophylactic”, “oophorectomy”, “ovariectomy”, and “colorectal cancer”. Manual search of reference lists in relevant review articles was also undertaken in order to identify other studies of interest. Citations were collated (and all duplicates removed) by using EndNote Reference Manager (V.X4, Thomson Reuters). The final search was performed on 1st February 2014.

In order to be included in the meta-analysis, studies had to be (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective or retrospective cohort studies; (2) reported data on at least one outcome following prophylactic oophorectomy vs no oophorectomy; (3) on the same occasion as primary curative colorectal cancer resection, with or without chemotherapy; and (4) no established diagnosis of ovarian neoplasia. Any primary cancer resection of the colon or rectum, regardless of laparoscopic or open technique was able to be included. Exclusion criteria were: histologically or radiologically established ovarian disease at time of colorectal resection, clearly visible or well established ovarian metastases at time of surgery, high clinical suspicion of ovarian metastases, known genetic diseases with higher risk of ovarian cancer such as lynch syndrome or HNPCC.

Two authors extracted data independently. Discrepancies in outcome extraction were resolved by discussion of the relevant data until consensus was achieved. Data extracted on study design included: randomisation technique, intervention arms, type of surgery. Details relating to the included patients were: number, age, indication for surgery, and site of cancer.

Prophylactic oophorectomy was defined as the removal of both ovaries where otherwise no surgical indication exists, in the absence of any evidence of histological or radiologically established metastases. Colorectal cancer was defined as any neoplastic process of the colon or rectum. Primary colorectal resection was defined as a curative resection (with or without adjuvant chemotherapy) of a primary colorectal cancer with no evidence of distant metastases at time of surgery.

The primary outcomes measured were local recurrence rate and overall 5-year survival. Secondary outcomes included immediate post-operative death, post-operative complications, and rate of distant metastases.

Assessment of bias was pre-planned, using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials[11], and the Newcastle-Ottawa score[12] for non-randomised studies. Scores were determined based on randomisation, patient selection techniques, comparability of the two intervention groups and the methods of measuring end points. Studies were deemed to be at low or high risk of bias based on these scores.

Meta-analysis of survival was carried out by calculation of a pooled hazard ratio (HR) from Kaplan-Meier curves using methods described by Parmar et al[13]. A HR of more than 1.00 represented worse survival for the experimental group (for example oophorectomy) vs the control group (no oophorectomy). The HR was considered significant if the 95%CI did not include 1.0 and P < 0.05. Data were analysed using Review Manager 5.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Due to the relatively high risk of bias from heterogeneity between studies, random effects modelling were used in order to estimate the mean of a distribution of effects of all included studies.

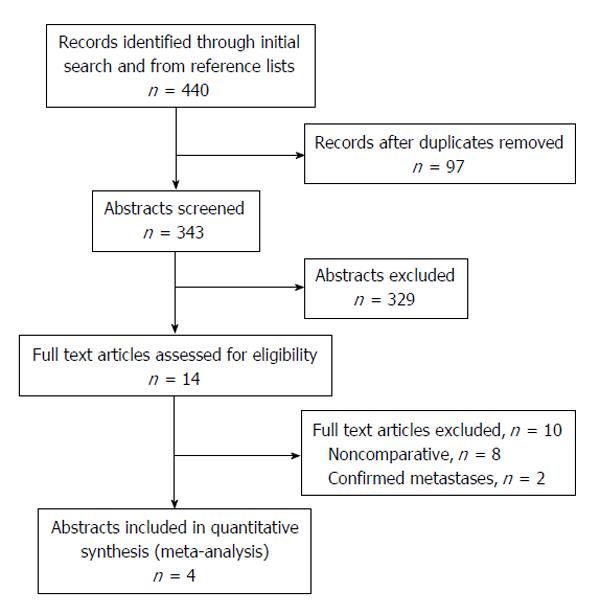

Initial literature search yielded 440 potential studies of interest, and after duplicates were removed a total of 343 study abstracts were reviewed, of which 14 of these abstracts were of interest. The majority of studies were excluded due to their study participants having known genetic disorders such as Lynch syndrome and HNPCC. Of the 14 full texts reviewed, 2 were excluded because the oophorectomy was undertaken with known diagnosis or strong suspicion of ovarian metastases. Eight studies were excluded because they did not adequately compare the outcomes of interest between the two groups. There were 4 studies[6,14-16] that could be included in the quantitative synthesis that met all inclusion criteria and directly compared the outcomes of interest (Figure 1 for preferred reporting item for systematic reviews and meta-analyses diagram).

The final analysis included four studies published between 1998 and 2004, with study periods ranging from 9 to 15 years[6,14-16]. There were a total of 627 patients, with 210 patients having undergone prophylactic oophorectomy, and 417 patients with colorectal resection only, from China, France, Greece, and the United States (summarised in Table 1). All four studies reported the mean age of the patients, and these ranged from 56.5 to 69 years.

| Ref. | Year | Study period | Setting | Design | Total patients | Patientsoophorectomy | Patients nooophorectomy | Mean age/yr (all) |

| Cai et al[14] | 2004 | 1991-2000 | Shanghai, China | Retrospective cohort | 267 | 43 | 224 | 56.5 |

| Sielezneff et al[15] | 1997 | 1980-1990 | Marseille, France | Prospective, non randomised | 90 | 39 | 51 | 65 |

| Tentes et al[16] | 2004 | 1987-2002 | Didimotichon Greece | Retrospective cohort | 124 | 54 | 70 | 69 |

| Young-Fadok et al[6] | 1998 | 1986-1996 | Mayo clinic, United States | RCT | 146 | 74 | 72 | 67 |

Although it had a very low attrition bias, the overall risk assessment scoring for the RCT put it at high risk of bias, due to lack of blinding, unclear randomisation and allocation. The remaining three cohort studies were all at high risk of bias, with the main concern being that selection of surgical group depended on patient choice in two studies[14,15] and was unclear in the remaining study[16]. None of the three cohorts studies scored more than 6 stars (out of a possible 9) according to NOS scoring.

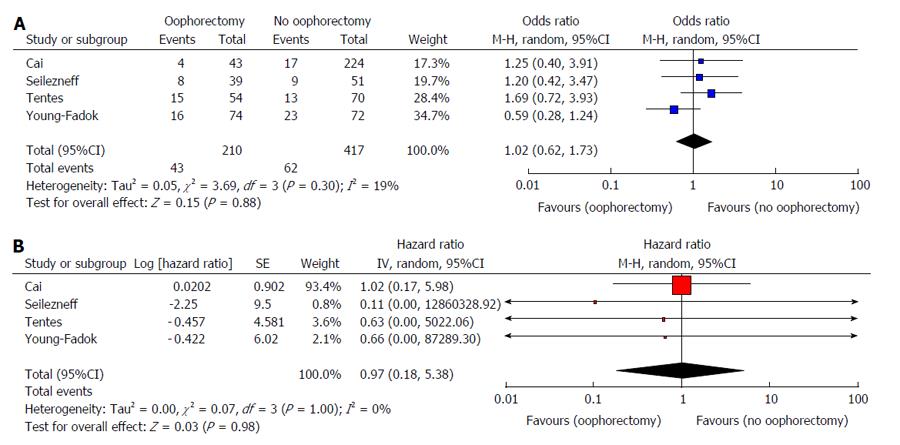

The primary endpoints of local recurrence and five-year survival are summarised in Table 2. There was no difference in the rate of local recurrence between patients who underwent prophylactic oophorectomy at the time of primary colorectal resection and those who did not (629 patients, four studies, OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.62-1.70, P = 0.920) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, no significant difference in five-year overall survival between these patients was found (636 patients, four studies, HR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.18-5.38, P = 0.980) (Figure 2B).

| No. of studies | No. of patients | No. of events | Random-effects model | Heterogeneity | ||||

| OR/HR | P | I2(%) | χ2 | P | ||||

| Oncological outcome | ||||||||

| Local recurrence | 4 | 627 | 105 | 1.04 (0.62, 1.73) | 0.88 | 19 | 3.69 | 0.300 |

| Five-year overall survival | 4 | 636 | - | 0.97 (0.18, 5.38) | 0.98 | 0 | 0.07 | 1.00 |

Only one study reported both mortality and complications in the immediate post-operative period[16]; there was no significant difference between mortality (oophorectomy group = 3/54 patients; non-oophorectomy group = 8/70 patients), or post-operative complications (oophorectomy group = 12/54 patients; non-oophorectomy group = 17/70 patients). Two studies reported distant metastases on follow up[14,15]; the first showed no significant difference between the groups (oophorectomy group = 13/43 patients; non-oophorectomy group = 16/224 patients), and similarly the second study showed no difference (oophorectomy group = 3/39 patients; non-oophorectomy group = 8/51 patients).

The current systematic review and meta-analysis specifically analysed the differences in outcomes between patients undergoing prophylactic oophorectomy at time of curative colorectal resection and those without oophorectomy amongst women with no known established genetic predisposition to ovarian cancer. We find that published evidence on this research question in the last 20 years is sparse, and no study has been published in the peer-reviewed literature in the last 10 years regarding this question. In the 4 studies that were meta-analysed, there are no trends towards favourable outcomes amongst the prophylactic oophorectomy patients. Using the random effects models, there are no differences in local recurrence, 5-year survival, or distant metastases between prophylactic oophorectomy and non-oophorectomy groups. However, where prophylactic surgery did take place, there were no extra risks of undertaking such surgery in terms of post-operative complications and mortality. All studies were at high risk of bias.

Studies examining prophylactic oophorectomy for women with genetic predisposition to ovarian cancer have shown favourable outcomes[9,17]. There is some evidence that women with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer should be screened for genetic predisposition to ovarian cancer so that risk-reducing surgery might be considered[18], and that such screening may yield long-term gains in life expectancy, which outweigh the short-term detrimental effects on quality of life from testing[19]. However, opinion has been divided for decades in the surgical community regarding prophylactic oophorectomy in the absence of genetic predisposition[7]. Prophylactic oophorectomy to improve survival in women with colorectal cancer was first suggested in the 1980s by the retrospective analysis of survival in a group of 571 women in the 1970s who had undergone curative resection for colon cancer, with a suggestion that 3%-8% of women might benefit[20]. Studies published before the data collection period of the current review had recommended prophylactic oophorectomy, but these were small, retrospective reviews[21-23]. Disagreement is compounded by varying and flawed methodology in these studies; for example one earlier study demonstrated no difference in recurrence rate or survival with prophylactic oophorectomy, but patient selection was based on surgeon preference, leading to bias in stage of colorectal cancer in each arm of the study[24].

There is some evidence that prophylactic oophorectomy results in an increased rate of premature death, cardiovascular disease, dementia, osteoporosis and Parkinsonism[25]. Oophorectomy before the age of 45 has been associated with an increased risk of death in a retrospective cohort study, especially for women not receiving hormone replacement therapy[26]. Therefore oophorectomy where not otherwise indicated has its own implications separate to the colorectal cancer resection; risk of these adverse outcomes must be balanced against oncological risks. Such risk vs benefits analysis may however be limited by fear of physiological and psychological adverse effects, as well as gaps in knowledge regarding risk[27], and these deficiencies must be addressed if informed decisions are to be made. If prophylactic ovarian surgery is not to be undertaken, close post-operative observation as well as ovarian metastatectomy when required appears to have a survival benefit, whilst avoiding the deleterious effects of oophorectomy in those who do not require it[28].

There is a striking paucity of data in the last 20 years regarding outcomes following prophylactic oophorectomy during resection of primary colorectal cancer, which limits this review. However such a finding is in itself important, since it implies that that there are limiting factors involved in studies which aim to test this research question. Indeed the only RCT in the last 20 years to have attempted to randomise patients was unable to accrue the anticipated number of patients after 10 years, and was forced to publish their preliminary results[6]. Although the authors of this RCT recommend further data collection, the final results have not been published, implying that the study may have been abandoned. The available evidence therefore must be based on only a handful of non-randomised cohort studies.

Currently, the published evidence cannot make an overwhelming case for prophylactic oophorectomy or ovarian conservation at the time of colorectal resection. The 4 studies analysed all individually reported no long-term survival benefit of prophylactic oophorectomy, and meta-analysis of all data confirmed this for the whole population. In practice, young women are not routinely screened for HNPCC and other genetic risks prior to colorectal cancer resection. Although there appears to be no benefit in offering oophorectomy to women with no known genetic disorder, such an informed choice might be more practical if high-risk women were screened prior to their planned colorectal surgery.

It is likely that future RCTs may not be feasible, and therefore the current review represents the best current evidence with which to base surgical decisions on this question. This review concludes that prophylactic oophorectomy cannot be recommended based on current evidence, but if it is performed has no extra risk of post-operative morbidity or mortality. If a patient would like to opt for prophylactic oophorectomy, surgery can only be undertaken with a full, frank discussion of the risks and lack of measurable benefits, and for those at high risk, results from genetic screening.

The development of ovarian metastases may lead to increased death in female colorectal cancer patients, and therefore preventative oophorectomy may be considered when undergoing colorectal cancer resection. Undertaking such surgery remains controversial, and therefore robust evidence is crucial. The authors aim to appraise the current evidence for prophylactic oophorectomy in patients undergoing primary curative colorectal cancer resection.

The topic of preventative surgery at the time of primary resection in of increasing importance as the cure rate for colorectal cancer improves. Cyto-reductive surgery and heated intra-peritoneal chemotherapy is being used with increasing frequency to salvage patients with recurrent or metastatic disease but carries a high morbidity and a risk of mortality. Preventative surgery may be able to avoid these risks.

The scientific literature regarding prophylactic oophorectomy at the time of primary colorectal surgery has not been reviewed since 2005 by Moran et al. Up to date review of evidence is required to inform colorectal surgeons about what is known about the risks and benefits of this procedure.

This systematic review and meta-analysis is relevant to all female patients undergoing colorectal cancer. It allows patients and their doctors have an informed discussion about whether prophylactic oophorectomy is in their best interests

Prophylactic oophorectomy-the removal of normal ovaries in an effort to prevent future disease.

In this study, the authors performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the association between prophylactic oophorectomy during primary colorectal cancer resection and risk of local recurrence and overall 5-year mortality. Rationale and aim for conducting this meta-analysis on this topic are clear.

P- Reviewer: Jiang WJ, Mashreky SR S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Lynge E, Jensen OM, Carstensen B. Second cancer following cancer of the digestive system in Denmark, 1943-80. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1985;68:277-308. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Tanaka H, Hiyama T, Hanai A, Fujimoto I. Second primary cancers following colon and rectal cancer in Osaka, Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1991;82:1356-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Birnkrant A, Sampson J, Sugarbaker PH. Ovarian metastasis from colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:767-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Perdomo JA, Hizuta A, Iwagaki H, Takasu S, Nonaka Y, Kimura T, Takada S, Moreira LF, Tanaka N, Orita K. Ovarian metastasis in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Acta Med Okayama. 1994;48:43-46. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Goéré D, Daveau C, Elias D, Boige V, Tomasic G, Bonnet S, Pocard M, Dromain C, Ducreux M, Lasser P. The differential response to chemotherapy of ovarian metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1335-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Young-Fadok TM, Wolff BG, Nivatvongs S, Metzger PP, Ilstrup DM. Prophylactic oophorectomy in colorectal carcinoma: preliminary results of a randomized, prospective trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:277-283; discussion 283-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hanna NN, Cohen AM. Ovarian neoplasms in patients with colorectal cancer: understanding the role of prophylactic oophorectomy. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2004;3:215-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Celentano V, Luglio G, Antonelli G, Tarquini R, Bucci L. Prophylactic surgery in Lynch syndrome. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schmeler KM, Lynch HT, Chen LM, Munsell MF, Soliman PT, Clark MB, Daniels MS, White KG, Boyd-Rogers SG, Conrad PG. Prophylactic surgery to reduce the risk of gynecologic cancers in the Lynch syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:261-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 580] [Cited by in RCA: 521] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Banerjee S, Kapur S, Moran BJ. The role of prophylactic oophorectomy in women undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:214-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18487] [Cited by in RCA: 24818] [Article Influence: 1772.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 12. | Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 3rd Symposium on Systematic Reviews: beyond the basics. UK: Oxford 2000; . |

| 13. | Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815-2834. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Cai GX, Xu Y, Tang DF, Lian P, Peng JJ, Wang MH, Guan ZQ, Cai SJ. Interaction between synchronous bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy in female patients with locally advanced colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:414-419. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sielezneff I, Salle E, Antoine K, Thirion X, Brunet C, Sastre B. Simultaneous bilateral oophorectomy does not improve prognosis of postmenopausal women undergoing colorectal resection for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1299-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tentes A, Markakidis S, Mirelis C, Leventis C, Mitrousi K, Gosev A, Kaisas C, Bouyioukas Y, Xanthoulis A, Korakianitis O. Oophorectomy during surgery for colorectal carcinoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8 Suppl 1:s214-s216. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, Narod SA, Van’t Veer L, Garber JE, Evans G, Isaacs C, Daly MB, Matloff E. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616-1622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1162] [Cited by in RCA: 1020] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang G, Kuppermann M, Kim B, Phillips KA, Ladabaum U. Influence of patient preferences on the cost-effectiveness of screening for Lynch syndrome. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18:e179-e185. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ladabaum U, Wang G, Terdiman J, Blanco A, Kuppermann M, Boland CR, Ford J, Elkin E, Phillips KA. Strategies to identify the Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:69-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ballantyne GH, Reigel MM, Wolff BG, Ilstrup DM. Oophorectomy and colon cancer. Impact on survival. Ann Surg. 1985;202:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Burt CV. Prophylactic oophorectomy with resection of the large bowel for cancer. Am J Surg. 1951;82:571-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | MacKeigan JM, Ferguson JA. Prophylactic oophorectomy and colorectal cancer in premenopausal patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:401-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Graffner HO, Alm PO, Oscarson JE. Prophylactic oophorectomy in colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1983;146:233-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cutait R, Lesser ML, Enker WE. Prophylactic oophorectomy in surgery for large-bowel cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:6-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shuster LT, Gostout BS, Grossardt BR, Rocca WA. Prophylactic oophorectomy in premenopausal women and long-term health. Menopause Int. 2008;14:111-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, de Andrade M, Malkasian GD, Melton LJ. Survival patterns after oophorectomy in premenopausal women: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:821-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cherry C, Ropka M, Lyle J, Napolitano L, Daly MB. Understanding the needs of women considering risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:E33-E38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lee SJ, Lee J, Lim HY, Kang WK, Choi CH, Lee JW, Kim TJ, Kim BG, Bae DS, Cho YB. Survival benefit from ovarian metastatectomy in colorectal cancer patients with ovarian metastasis: a retrospective analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:229-235. [PubMed] |