Published online Mar 28, 2015. doi: 10.5412/wjsp.v5.i1.127

Peer-review started: July 19, 2014

First decision: November 18, 2014

Revised: December 5, 2014

Accepted: December 18, 2014

Article in press: December 19, 2014

Published online: March 28, 2015

Processing time: 257 Days and 17.8 Hours

Retrorectal (also known as presacral) tumor (RT) is a rare disease of retrorectal space. They can be classified as congenital, inflammatory, neurogenic, osseous, or miscellaneous. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic mass discovered on routine rectal examination, but certain nonspecific symptoms can be elicited by careful history and physical examination. The primary and only satisfactory treatment is surgery for RTs. Three approaches commonly used for resection are abdominal, transsacral, or a combined abdominosacral approach. Prognosis is directly related primary local control, which is often difficult to achieve for malignant lesions.

Core tip: Since retrorectal tumors are rare in surgical practice an ordinary surgeon will have been faced a number not more than a fingers of one hand in his lifelong carrier. Diagnostic and surgical practice should be fulfilled by the small but well documented case series, reviews and meta-analyses based on them.

- Citation: Uçar AD, Erkan N, Yıldırım M. Surgical treatment of retrorectal (presacral) tumors. World J Surg Proced 2015; 5(1): 127-136

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2832/full/v5/i1/127.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5412/wjsp.v5.i1.127

Retrorectal tumor (RT) is a rare disease. Average of two patients can be diagnosed annually in an urban area[1]. An ordinary surgeon will have been faced with a few cases in his lifelong carrier. Even many malignant cases can be encountered and necessitate aggressive surgical interventions, fortunately majority are benign. Since misdiagnosis or incorrect operative approach in case of RTs can cause serious complications, always keeping in mind as a differential diagnosis, thorough working knowledge of the etiology, presentation and treatment are essential. In a small number of patients with RT, Singer et al[2] reported that approximately 4.7 unnecessary diagnostic but unrelated interventions have done before definitive diagnosis.

The first reported case of RT in 1847 by Emmerich was an adult teratoma[3]. In 1885, a second case of RT (dermoid cyst) was reported in a young woman’s autopsy[4]. Page reported the first successful excision of a RT in 1891[5]. The first case harboring malignancy was a tail gut cyst described by Ballantine[6] in 1931.

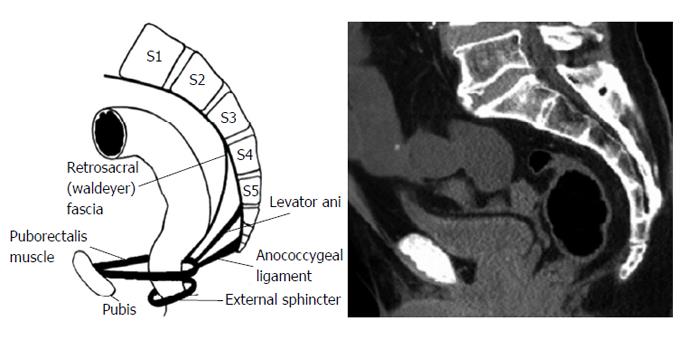

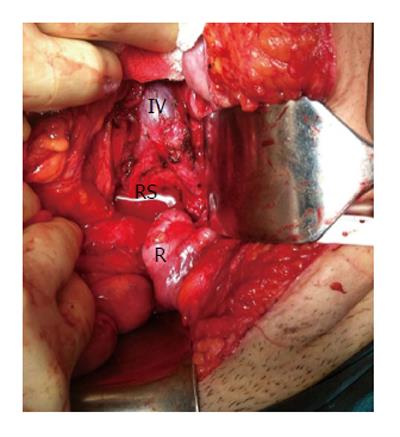

The area of retrorectal space (RS) is delineated posteriorly by presacral fascia overlying the sacrum and anteriorly by fascia propria of the rectum. Lateral borders include different structures like ureters, iliac vessels and lateral borders of the rectum. It’s superior and inferior ends are peritoneal layer of the rectum and Waldeyer’s fascia respectively (Figures 1 and 2).

Since multiple embryologic structures rise up in RS, this area can contain variety of tumors harboring diverse histopathology. For this reason this space may be the most crowded point in which different subspecialties such as surgeons, obstetricians and gynecologists, urology, neurosurgeons, orthopedics encounter each other while managing a lesion herein.

Even though RTs are very common malignancy in the childhood, they are rare in the adults, occurring 1 of 40000 to 63000 admissions at a reference hospital admissions. Different from adults, infants frequently present with an externally visible sacrococcygeal masses showing malignant transformation in untreated cases[7]. Benign lesions in RS are more common in females whereas malignant tumors have an equivalent distribution[1]. While cystic malignancies have been described, malignancy is more common in solid lesions with a rate of 9% to 45%[8]. Estimated incidence of RT in adult population is 0.0025-0.014[9]. Retrospective series shows that 1 to 6 patients are diagnosed annually in major referral centers[1]. After 20851 proctoscopies performed in a single institute, only 3 precoccygeal cysts can be diagnosed per year[10].

The most of the knowledge accumulations are derived from individual case reports and small numbered case series. There are few cohort series with large numbers which span 12 to 35 years interval, reflecting that major referral centers will be accepted approximately 1.4 to 6.3 patients per year[1]. In fact there should be some patients who were overlooked and this may reduce the calculated incidence rate. There is only one large series of 63 patients during 30 years period from a non-referral center[1]. According to this study from an entire metropolitan area, annually diagnosed 2 patients are more representative number to make a decision of incidence in a definite area.

The most frequently used classification system separates RTs into five categories: congenital or developmental, neurogenic, osseous, inflammatory, and miscellaneous[1]. This classification was further divided into benign and malignant because therapeutic approach is mainly based on the histopathology (Table 1)[11]. Other classification system divides RTs into four distinct groups; congenital vs acquired and benign vs malignant clustering in similar characteristics, diagnosis, and management[12].

| Source of origin | Histopathology | |

| Congenital or | Benign | Developmental cysts |

| developmental | Dermoid cysts | |

| Epidermoid cysts | ||

| Tail gut cysts | ||

| Enteric (rectal) duplication | ||

| Anterior sacral meningocele1 | ||

| Teratoma | ||

| Adrenal rest tumors | ||

| Malignant | Chordoma1 | |

| Teratocarcinoma | ||

| Inflammatory | Granulomas (foreign body, chronic) | |

| Perineal/pelvirectal abscess or fistula | ||

| Neurogenic | Benign | Neurofibroma |

| Neurolemmoma (schwannoma) | ||

| Ganglioneuroma | ||

| Malignant | Ependymoma | |

| Ganglioneuroblastoma | ||

| Neurofibrosarcoma | ||

| Osseous | Benign | Osteoma Sacral bone cyst |

| Osteoblastoma | ||

| Osteogenic sarcoma | ||

| Giant cell tumor | ||

| Malignant | Ewing's tumor | |

| Chondromyxosarcoma | ||

| Osteogenic sarcoma | ||

| Myeloma | ||

| Miscellaneous | Benign | Lipoma |

| Fibroma | ||

| Leiomyoma | ||

| Hemangioma | ||

| Endothelioma | ||

| Desmoid tumor | ||

| Lymphangioma | ||

| Ectopic kidney | ||

| Malignant | Fibrosarcoma | |

| Liposarcoma | ||

| Leiomyosarcoma | ||

| Metastatic disease |

Congenital lesions are embryologic remnant which has been present from the birth. They account 55% to 75% of all presacral lesions with subgroups of developmental cysts, chordomas, anterior sacral meningoceles, rectal duplications and adrenal rest tumors[1].

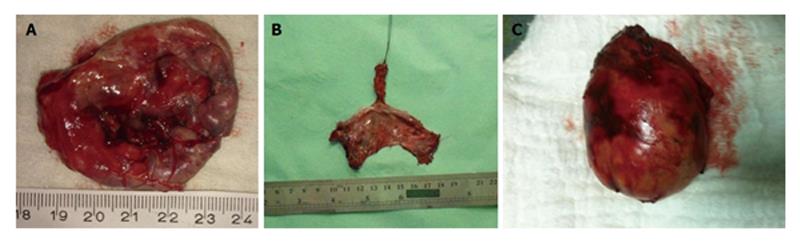

Developmental cysts: About 60% of congenital RTs are developmental cysts originating from different embryologic origin. There is 1:2 female predominance[13]. This predilection may be the result of more frequent routine rectal or pelvic examination in female population than males which makes females more likely for diagnosis[14]. Depending on the origin of embryonic cell, they can be epidermoid, dermoid, tail gut cyst or teratomas. Epidermoid and dermoid cysts are derived from ectodermal tube closure defect. Dermoid cysts made up with more matured components and comprise dermal appendages like hair follicles and sweat glands whereas epidermoid cysts have squamous epithelial lying (Figure 3). Women in between 4th or 5th decades are more prone to develop dermoid and epidermoid cysts. These cysts likely contain viscid green-yellow material unless infected[15]. The next and less frequent congenital lesion sometimes referred as cystic hamartoma is tail gut cysts. Glandular, mucous producing columnar epithelium in these cysts explains it’s derivation from tail gut remnants. Although cyst wall may contain scattered bundles of smooth muscle fibers, muscular and serosal coat is not present. Malignant degeneration is rare in tail gut cysts.

Teratomas: Even sacrococcyx is the most common location for teratomas in neonates, it is rare in adults. Teratomas, which have 5% to 10% malignant potential can give rise to multiple solid or cystic lesions containing various tissue types like respiratory, nervous and gastrointestinal system epithelium[16]. Nearly 30% of resected adult teratoma specimens harbor malignancy. The one tip to predict whether it is benign or malign is relation to adjacent structure. The tendency of malignant teratomas to adhere coccyx, rectum and other visceral organs is not seen in benign lesions.

Chordomas: Chordoma is the most common malignant and the most extensively studied RT. It is the second most common RT in RS occurring in three of seven patients[17]. Even one-third occurs in RS, they can be found anywhere in vertebral column[18]. Slow growing nature of chordoma postpones the diagnosis until 40 to 60 years of ages[1]. Long standing vague pain and symptoms associated with nerve compression like incontinence or impotence are frequent presentations. These frequently lobulated, gelatinous masses that attack and break down the neighboring structures need complete resection in order to prevent recurrence. The typical radiological finding for chordoma is “Fang” sign, the finding of sacral bone destruction. Recurrence rate is as high as 44% and because these recurrences are locally aggressive, patients should be warned for probable postoperative sequelae from minor urinary incontinence to paralysis[19]. Chordomas are more common in males with an expected male/female ratio of 2:1[14].

Anterior sacral meningocele: Anterior sacral meningocele is the third group of congenital RT. It is a dural hernial sac containing cerebrospinal fluid as a continuation of subdural space from a defect in the sacrum. Dural connection causes increase in cerebrospinal fluid pressure during straining or defecation. Anterior sacral meningoceles are more common in females and can present with recurrent meningitis[10].

Miscellaneous: The last category of congenital RT is adrenal rest tumors and rectal duplications. The latter can contain mucosa with crypts and villi, smooth muscle and serosa components of intestine because they are remnants of duplicated rectum. Adrenal rests tumors are very sporadic and must be managed like an ectopic pheochromocytoma.

Inflammatory RTs are less common than congenital ones. They may be residues of foreign bodies of any kind. Tuberculosis, granulomatous disorders, perianal abscess, diverticulitis resulting pelvic abscess and fistulas can cause chronic inflammatory masses in the RS.

Neurogenic tumors tend to be large and account 10% of RTs. This category includes neurofibromas, neurolemmomas, ependymomas, ganglioneuromas, and neurofibrosarcomas. Even benign lesions constitutes two thirds of neurogenic RTs, severe neurological sequelae can be seen if these lesions are originated from the spinal cord. Neurogenic and osseous RT can be benign or malignant. Benign ones often require complete resection but recurrence rate is high in osseous lesions.

The last but not least group of RT constitutes masses such as metastatic disease from rectum, sarcomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, lymphangiomas, lymphomas, fibrosarcomas, liposarcomas, hemangiomas and others that can be found anywhere else in the retroperitoneum[8]. They constitute 10% to 25% of all RTs[1].

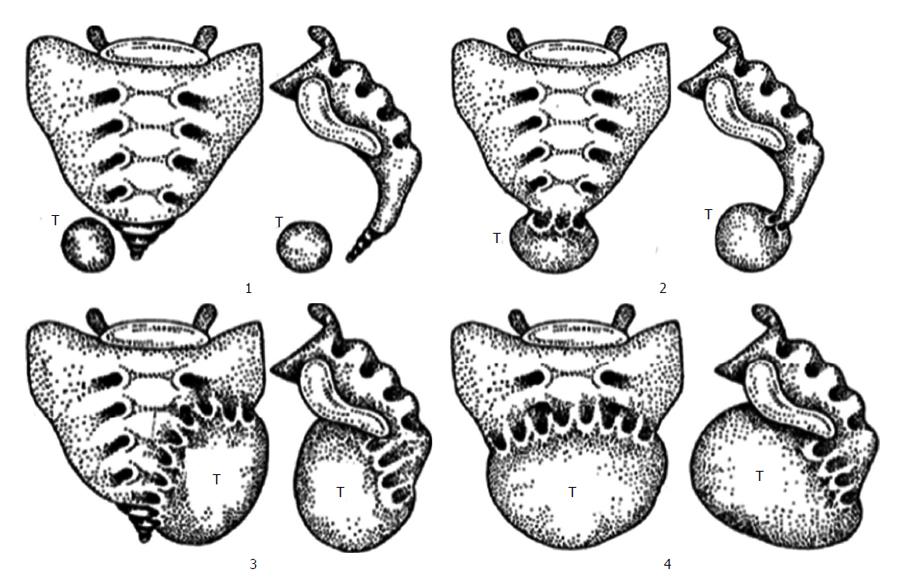

However these classifications do not consider the location of RT in the RS which is important determinant for operative and pathologic considerations. A suggestion of a classification system based on the tumor emplacement to facilitate surgical strategy and postoperative sequelae prospection (Figure 4)[20]. According to this classification, type 1 refers to RTs without any connection to the sacrum. Type 1 RT is at the coccyx level (below S3) and separate from the bony trunk of sacrococcyx. It can easily be separated from surrounding structures and removal is not difficult[2]. Type 2 RT is also settles with the same level as type 1 but has connection with the coccyx and/or sacrum. Their surgical resection promise no neurologic deficit[12]. Type 3 RT requires a unilateral resection of the sacral nerve(s), probably resulting fecal and/or urinary incontinence because type 3 RT involves the sacrum at or above the S3 nerve root unilaterally. Type 4 RT has large communication with the sacrum at or above S3 bilaterally in which permanent sphincter deficit is almost unavoidable.

Further division of these four types is A; resection of the adjacent sacral soft tissue and bone is mandatory without adjacent organs and B; resection of organs such as rectum, bladder is obligatory.

Asymptomatic tumor discovered on reckless pelvic or rectal screening investigation is the most common type of presentation[8]. That’s why most patients don’t have a positive family history despite the majority of RTs are congenital[11]. On the other hand some authors report that nearly 97% of RTS can be and are diagnosed on physical examination[21]. Every physician should put RT in differential diagnosis list on rectal or pelvic examination in order not to miss any which may be the only case of his lifelong carrier as described above.

RTs may cause mild or imprecise symptoms. Benign lesions frequently remain silent for a long period of time. Sacrococcygeal pain is the most common presenting complain in malignant or infected cases of RT[21]. Nature of pain is mostly low back or rectal pain. Presentation of pain in benign and malignant RTs is approximately 30% and 87% respectively[21]. Male gender and older age (> 60) are other predisposing factors for malignancy. Persistent pain at low back, pelvis, and buttocks which is increased by sitting is usual in chordomas.

RT can present with infection reflected as a small, dimples posterior to the anus and below the linea dentata[1]. Misdiagnosis of a retrorectal lesion as a fistula, pilonidal sinus or perianal abscess and any delay in proper management will be unavoidable if failure to understand actual pathology[1]. Incontinence of urine or stool, bowel habitus changes like constipation, sensation of inadequate emptying or tapering stools are sequelae of the change in the rectal angle at the puborectalis muscle due to mass effect. This mass effect can create vaginal canal obstruction and consequent life threatening dystocia during child birth. Anterior sacral meningocele should always be kept in mind if there is a history of headaches after straining, defecation, intercourse and existence of repeated meningitis in a case with a palpable retrorectal mass.

Rigorous rectal examination is crucial because the most lesions are soft, compressible, and can easily be misdiagnosed if the physician does not awake for a RT probablity[1]. By this way not only because digital rectal examination can establish the diagnosis in > 90% of the patients, but also it can help to define the proximal level of the RT, therefore the surgical approach[11,21].

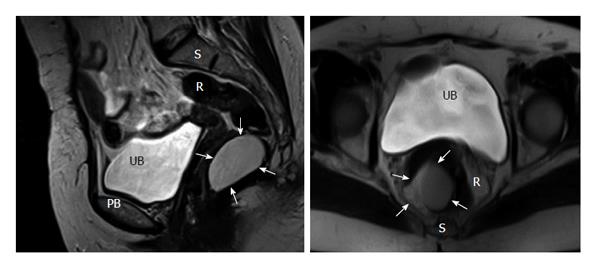

Evaluation of RT begins with plain radiographs. Clinicians usually fail to value signs and symptoms of RT and consequently misdiagnoses even after extensive radiological workup. Pelvic bone demolition, proposing a malignancy or a chordoma, and numerous dense calcifications proposing a benign teratoma are helpful findings of plain radiographs. Smooth-edged, bowl-shaped border of the sacrum without clear bony demolition of the pelvis (known as “scimitar sacrum”) proposes the existence of a sacral meningocele. Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) appears to be useful in the diagnosis of RTs. TRUS was found to have a sensitivity of 100% when combined with proctoscopy[2]. TRUS can predict rectal muscularis connection and type of operation.

Either computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were became the standard for evaluation of RTs. Very small cystic or solid tumors, sacral contribution or attack to neighboring structures can easily be detected with CT[21]. MRI is more beneficial in outlining soft-tissue planes, assessing bony invasion and nerve involvement with its superior tissue contrast resolution to CT scan[11]. Histologic estimation of the RT may be best achieved with MRI[2].

Preoperative histologic diagnosis is mandatory when there is solid or heterogeneously cystic tumor[11]. Biopsy is indicated when the lesion seems to be unresectable and a definitive histopathology is required to guide adjuvant therapy. Purely cystic lesions rarely necessitate biopsy because they are usually benign and biopsy carries the risk of infection. Unnecessary biopsy can cause tumor seeding, infection of the previously sterile cystic lesions, fistula formation and fatal case of meningitis in patients with anterior sacral meningocele or exacerbates morbidity and mortality of subsequent operations[21].

The operation team should consider the way of biopsy since needle tract must be included within the specimen. Transperitoneal, transretroperitoneal, transvaginal, and transrectal biopsies are not recommended since biopsy tract may not be excised. Transrectal or transvaginal biopsies may also lead to infection, more complex and difficult excision, increased postoperative complications and recurrence. According to the literature, the best method is transperineal or parasacral since by this way biopsy tract can likely to be kept within the area of the upcoming surgical excision. It is logical to mark needle insertion pathway with methylene blue dye for keeping the biopsy tract within the resection specimen[22].

The consideration of the role of biopsy for the management of RT was concluded that preoperative biopsy of RT is safe and more concordant with postoperative pathology than imaging. Given the significant differences in therapeutic approach for benign vs malignant solid or heterogeneous solid-cystic RTs, as well as the current limitations of imaging, a percutaneous preoperative biopsy should be obtained to guide management decisions. Type of surgical resection and the role of neoadjuvant chemoradiation also necessitate actual histology. Moreover, since all malignant RTs require a wide resection including sacrectomy, preoperative tissue diagnosis is mandatory to avoid patients with benign RT from urinary and sexual dysfunction, or other unwanted outcomes[23].

Surgery is a sole treatment of RTs. Probable infection and malignancy or switching into malignant cells are some convincing reasons. If currently sterile and benign looking cystic lesions once infected, they will adhere to the adjacent structures making the surgery difficult, increase the postoperative complication and recurrence rates.

Three main operative approaches for the resection of RTs are existing; anterior or abdominal, posterior or transsacral and combination of both.

Anterior approach is suitable for tumors at higher location having the lowest border above the 4th sacral bone. Absence of sacral involvement is essential for this approach. This kind of surgery has advantages of good disclosure of adjacent pelvic structures such as iliac vessels and ureters (Figure 5). Throughout the abdominal approach, rectum is first isolated and separated from resection area and after ligation of middle sacral and internal iliac vasculatures, presacral fascia is dissected. Surgeon should be in great care during tumor excision for presacral hemorrhage because the middle sacral blood vessels and the presacral venous plexus are in this region. Possible perineal necrosis can be prevented by preservation inferior gluteal artery which is terminal branch of anterior division of the internal iliac artery. The main cause of intraoperative death is hemorrhage of the presacral venous plexus. Traditional hemostasis methods may not be enough and troublesome bleedings can be overwhelmed by some challenging preventive measurements such as temporary gauze tamponade, bone wax or breast size implanter[24].

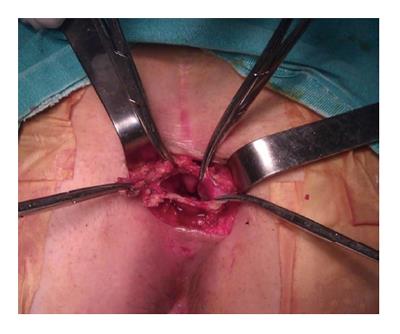

This procedure is suitable for low lying tumors which are not extending beyond 4th sacral element. Usual length of a finger can extend up to 4th sacrum. If the proximal end of the tumor is felt by digital sensation, this means that there is no extension beyond that point. The patient is positioned in a prone jack-knife position, preferably buttocks are separated apart (Figure 6). A transverse incision overlying the coccyx offers good disclosure of the retrorectal space especially in case of nerve involvement. A longitudinal incision may be used alternatively on the lower sacrum to the level of anoderm while taking care for not to cause any injury to external sphincter. After dividing the subcutaneous fat, the levator muscles and the anococcygeal ligament lying deep to the lumbosacral fascia are exposed. Transection of anococcygeal ligament allows mobilization of the coccyx. Coccyx can be transected to provide sufficient exposure for dissection, the gluteal muscle may be separated, and sacrectomy of S4-S5 can be achieved afterwards. Separation of the plane between the tumor and the mesorectum will be easy. The major disadvantages of posterior approach are injury to the lateral pelvic nerves and absence of control over pelvic vessels. While comparing with anterior or combined procedures, probable hemorrhage can be lowered by posterior method[25]. If the lesion is benign, there should be an identifiable fat plane between the mesorectum and RT provided that there was no infection before. In case of cystic and/or small lesion, the surgeon can place the nondominant hand index finger with double-glove in the anal canal and lower rectum and then depress the tumor through the incision. Undesired injury to the rectal wall during the dissection can also be prevented with this manner. The posterior approach is embraced of different techniques such as transsphincteric, transsacral, transrectal, transanorectal, and transsacrococcygeal approaches. Every one of these techniques has its own losses and benefits and can be chosen based on the characteristics and site of the tumor and the surgeon’s preferences.

Ruptured transrectal cysts and solid but well delineated lesions extending rectal muscular layer with suitable level should be subjected to this kind of surgical approach. A modification of this approach is intersphincteric resection of RT which starts with retrorectal space access via intersphincteric plane or a transvaginal incision, when the tumor is low enough and not in the midline, lying between vaginal wall and rectal muscularis layer. Anal sphincter damage confronts us during the above incisions but one can avoid the possibility of sacral nerve injury, postoperative urinary retention and unintentional rectal perforation with these cuttings.

This procedure is suitable for the tumor extending both vertical sides of the 4th sacral vertebra. Operation begins with the patient in modified lithotomy position and entering the retroperitoneal space through the areolar plane between the mesorectum and the presacral fascia, to gain access for dissection of the upper part of the lesion. While going down to the deep pelvis, identification of planes between the tumor and surrounding tissues will become more difficult, than patient may be repositioned in the jack-knife position for the perineal phase of the procedure. An incision is then made over the sacrum and coccyx through the anus, while being awake not to damage external sphincter. Division of anococcygeal ligament and retraction of levators can be done afterwards. The gluteus maximus muscles are then retracted away and the sacrospinous, sacrotuberous ligaments, and piriformis muscles are divided bilaterally to delineate the sciatic nerve. Any dural openings should be closed to prevent cerebrospinal fluid leakage or infection. One S3 nerve should be preserved to maintain proper fecal and urinary function. Colostomy should be matured if unilateral preservation of the S3 is not possible. In case of benign or have a low relapse probability, colonic continuation can be achieved with anastomosis but diverting ileostomy should be considered.

Major advantages of this approach appear when infection or inflammation cause disappearance of the dissection planes or exposure of the neighboring structures like rectum, ureters, iliac vessels as well as nerve roots are obligatory. This is a case in chordoma in which partial sacral excision extending above S-3 is necessary. Complete and one piece tumor excision with a hemisacrectomy can be accomplished after exposure of the sacrum through the posterior approach. Bone allograft, iliosacral screws, and Galveston type fixation are necessary for lumbopelvic stabilization as bony reconstruction after the end of tumor resection[26]. Transpelvic vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap reduces wound complications[27]. In case of anterior sacral meningocele, reverse abdominoperineal approach is the operation of choice because the communications can easily be recognized by posterior approach, and then conveniently sutured at the anterior phase.

Nearby location of the RT to the rectum and the anal canal necessitate good bowel preparation before surgery. Ureteral catheter should be placed to feel and protect the ureters if indicated. Successful resection for highly vascular lesions or for reduction of blood loss during surgery can be facilitated with transcatheter arterial embolization of tumors. Beside of decreased blood loss and more clear surgical vision, possible elimination for the need of anterior approach, and R0 resection of the sacral chordoma will be pleasing[28].

While planning the surgery, coccyx resection consideration is important. Routine resection of the coccyx this is mandatory if the coccyx is free of malignancy the histopathology is not clear. Local recurrence rate rise up to 25% to 56% if RT resection is not achieved with coccyx resection by transsacral approach[29].

Radical surgeries such as total sacrectomy in case of first sacral bone involvement has been tried out but structural and neurologic sequels are very high[20]. Postoperative neurogenic bladder rate up to 15% and fecal incontinence at a rate of 7% cause severe social life problems[21]. Immolation of sacral nerves bilaterally creates this problem in almost always every cases but unilateral sacrification can give a chance to preserve these functions well[30]. Normal continence and defecation can be protected not only with conservation of S-1 and S-2 bilaterally but also at least one S-3 nerve root is required to protect normal bowel and anorectal function[8]. Urinary and fecal incontinence and impotence in males are almost inevitable after sacrification of S2-S4 nerve roots at both side. Bilateral S2 root preservation leads to mild and reversible bladder sphincter dysfunction which responds to rehabilitative treatment in certain extend.

Laparoscopic approach is reported to be feasible and safe. Surgical trauma reduction, better visualization of the deep structures in the presacral space and less vascular and neurological injuries are benefits of laparoscopy[31]. There is a case of RT operated with the help of robotic device. Beside of the known benefits of laparoscopy, such as pain, scar, hospital stay reduction, the greatest advantage of a robotic approach to the PS is improving surgical technique to allow retraction and handiness provided by the instruments in this confined area. Longer operative time and high cost are two potential disadvantages of the robotic technology expected to be overcome[32].

Demonstration of the efficacy of adjuvant treatment in rare and heterogeneous disease of RTs is difficult. Even though it has a minimal role in management of RTs, adjuvant chemoradiotherapies have been tried in some surgically unresectable lesions. Chordomas are the most aggressive and radiation resistant tumor at this location but high dose radiation therapy has been tried[33]. Radiation of the affected area with neutrons by high linear energy transfer therapy or charged particle carbon ion radiotherapy (CIRT) in inoperable and recurrent chordomas was able to show 54% local control rate[34]. After 3 years follow up, conventional radiotherapy and CIRT demonstrated 35% and 73% control rates respectively. Big radiosensitive tumors can be decreased in size and this can help to preserve vital elements of the pelvic region. Direct radiation to smaller field also decreases the patient morbidity[35]. However long-term response to this therapy is doubtful.

Inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor’s tyrosine kinase domain, such as Imatinib, Cetuximab, gefitinib has been shown to be effective in the management of recurrent and metastatic chordoma[36,37]. Proceedings with Imatinib chemotherapy have helped to increase progression-free survival in advanced chordomas cases[22]. Some RTs such as Ewing sarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma, neurofibrosarcomas, and desmoid tumors necessitate neoadjuvant therapy.

Patients with malignant RT have significantly worse perioperative and long-term complications when compared with the benign counterparts. Even the type of operation has no impact on the long-term complications, long term survival can be reduced 70% with proper oncologic resections[38]. Local recurrence rate increases from 28% to 64% if the tumor was violated during the surgery which brings to mind a well-known “no touch” subject in colorectal cancer surgery[39].

Overall survival for benign RTs was reported to be nearly 100% in most studies[8]. The recurrence rate was reported to be 0%-11.1% for benign and 47.6%-75% for malignant RTs[12,21]. In case series, the local recurrence rate was reported to be 6.7% to 11.11% for presacral lesions, 15% for developmental presacral cysts, 47.6% for malignant RTs, and 75% for chordoma[11,12].

One study demonstrating 15% recurrence rate for developmental cysts but it was soon understood that most of these relapses happened in patients with teratomas, than the frequency reduced once en bloc removal of the coccyx which frequently harbors neoplastic cells[21]. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center demonstrated difficult local control with 48% local recurrence and 17% overall survival rates for malignant lesions[40]. More than 20% ten-year survival and 96% recurrence rates were talked about chordomas in early studies but outcomes have improved with improvements in surgical procedures and management strategies[41]. As reported more recently, 84% ten year survival rate with 44% recurrence rate were achieved[19]. A study including 400 cases of chordomas within the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Result program demonstrated that five and ten year survival rate for sacral chordomas were 74% and 32% respectively[18]. The most important point in determination of prognosis of chordoma is negative surgical margin. Unfortunately some authors have concluded that total excision of chordoma is nearly impossible and recurrence is inevitable[41].

It should be stressed once more that R0 excision at the first operation is crucial because reexcision of recurrent RT is much more complicated and hopeless[11].

RTs can be classified as congenital, inflammatory, neurogenic, osseous, or miscellaneous and each of the above categories is subdivided as benign and malignant lesions. Common or nonspecific perianal, perineal or abdominal symptoms should be elicited with careful history. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic mass discovered on routine rectal examination. High index of suspicion in any patient coming with a posterior mass on digital rectal examination, or a post anal dimple, particularly in association with a fistula refractory to multiple operative interventions is essential. Tumors in this area can present diagnostic and therapeutic difficulty because RTs are located in surgically difficult anatomic location with different tissue types and etiologies. When tumor seeding, fecal fistula, meningitis, and abscess formation are brought to mind, biopsy of these lesions should be avoided to as much as possible. After appropriate diagnostic interventions, complete surgical resection remains the primary and only satisfactory treatment. There are three approaches commonly used for resection; abdominal, transsacral, or a combined abdominosacral approach. Coccyx should be excised en bloc only when involved with tumor or existence of doubtful malignant potential. R0 resection at the first surgical intervention is the most important determinant of prognosis but it may be difficult to achieve for malignant and recurrent lesions.

P- Reviewer: Baba H, Morioka D, Parsak C

S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Uhlig BE, Johnson RL. Presacral tumors and cysts in adults. Dis Colon Rectum. 1975;18:581-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Singer MA, Cintron JR, Martz JE, Schoetz DJ, Abcarian H. Retrorectal cyst: a rare tumor frequently misdiagnosed. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:880-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Kiderlen F. Teratoid tumors of the sacral region from a clinical standpoint with presentation of pertinent cases. Deutsch Z Chir. 1899;52:87. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Page F. Large extraperitoneal dermoid cyst successfully removed through an incision across the perineum, midway between the anus and the coccyx. Br Med J. 1891;1:406-409. |

| 6. | Ballantine EN. Sacrococcygeal tumours. Adenocarcinoma of a cystic congenital embryonal remnant. Arch Pathol. 1931;14:1-9. |

| 7. | Altman RP, Randolph JG, Lilly JR. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: American Academy of Pediatrics Surgical Section Survey-1973. J Pediatr Surg. 1974;9:389-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hobson KG, Ghaemmaghami V, Roe JP, Goodnight JE, Khatri VP. Tumors of the retrorectal space. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1964-1974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wolpert A, Beer-Gabel M, Lifschitz O, Zbar AP. The management of presacral masses in the adult. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Jao SW, Beart RW, Spencer RJ, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM. Retrorectal tumors. Mayo Clinic experience, 1960-1979. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:644-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dozois EJ, Jacofsky DJ, Dozois RR. Presacral tumors. The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery. New York: Springer 2007; 501-514. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Lev-Chelouche D, Gutman M, Goldman G, Even-Sapir E, Meller I, Issakov J, Klausner JM, Rabau M. Presacral tumors: a practical classification and treatment of a unique and heterogeneous group of diseases. Surgery. 2003;133:473-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Stewart RJ, Humphreys WG, Parks TG. The presentation and management of presacral tumours. Br J Surg. 1986;73:153-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cheng EY, Ozerdemoglu RA, Transfeldt EE, Thompson RC. Lumbosacral chordoma. Prognostic factors and treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1639-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ludwig KA, Reynolds HL. Retrorectal tumors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2002;15:285-293. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Killen DA, Jackson LM. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in the adult. Arch Surg. 1964;88:425-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gordon PH. Retrorectal tumors. Principles and Practice of Surgery for the Colon, Rectum and Anus. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing 1999; 427-445. |

| 18. | McMaster ML, Goldstein AM, Bromley CM, Ishibe N, Parry DM. Chordoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1973-1995. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 745] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bergh P, Kindblom LG, Gunterberg B, Remotti F, Ryd W, Meis-Kindblom JM. Prognostic factors in chordoma of the sacrum and mobile spine: a study of 39 patients. Cancer. 2000;88:2122-2134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Losanoff JE, Sauter ER. Retrorectal cysts. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:879-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Böhm B, Milsom JW, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Church JM, Oakley JR. Our approach to the management of congenital presacral tumors in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1993;8:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Neale JA. Retrorectal tumors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:149-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Merchea A, Larson DW, Hubner M, Wenger DE, Rose PS, Dozois EJ. The value of preoperative biopsy in the management of solid presacral tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:756-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Braley SC, Schneider PD, Bold RJ, Goodnight JE, Khatri VP. Controlled tamponade of severe presacral venous hemorrhage: use of a breast implant sizer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:140-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Buchs N, Taylor S, Roche B. The posterior approach for low retrorectal tumors in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:381-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Althausen PL, Schneider PD, Bold RJ, Gupta MC, Goodnight JE, Khatri VP. Multimodality management of a giant cell tumor arising in the proximal sacrum: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:E361-E365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Miles WK, Chang DW, Kroll SS, Miller MJ, Langstein HN, Reece GP, Evans GR, Robb GL. Reconstruction of large sacral defects following total sacrectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2387-2394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dozois EJ, Malireddy KK, Bower TC, Stanson AW, Sim FH. Management of a retrorectal lipomatous hemangiopericytoma by preoperative vascular embolization and a multidisciplinary surgical team: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1017-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Koh CC, Wang NL. An unusual neurogenic cystic tumor. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:743-745. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Gunterberg B. Effects of major resection of the sacrum. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;162:9-38. |

| 31. | Nedelcu M, Andreica A, Skalli M, Pirlet I, Guillon F, Nocca D, Fabre JM. Laparoscopic approach for retrorectal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4177-4183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Agorastos S, Alex A, Feldman J, Kuncewitch M, Deutsch G, Siskind E, Nicastro J, Coppa GF, Conte C, Beg M. Robotic resection of retrorectal tumor: an alternative to the Kraske procedure. Journal of Solid Tumors. 2013;3:13-16. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Amendola BE, Amendola MA, Oliver E, McClatchey KD. Chordoma: role of radiation therapy. Radiology. 1986;158:839-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Breteau N, Demasure M, Favre A, Leloup R, Lescrainier J, Sabattier R. Fast neutron therapy for inoperable or recurrent sacrococcygeal chordomas. Bull Cancer Radiother. 1996;83 Suppl:142s-145s. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhang H, Yoshikawa K, Tamura K, Sagou K, Tian M, Suhara T, Kandatsu S, Suzuki K, Tanada S, Tsujii H. Carbon-11-methionine positron emission tomography imaging of chordoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33:524-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Casali PG, Messina A, Stacchiotti S, Tamborini E, Crippa F, Gronchi A, Orlandi R, Ripamonti C, Spreafico C, Bertieri R. Imatinib mesylate in chordoma. Cancer. 2004;101:2086-2097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hof H, Welzel T, Debus J. Effectiveness of cetuximab/gefitinib in the therapy of a sacral chordoma. Onkologie. 2006;29:572-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Casali PG, Stacchiotti S, Sangalli C, Olmi P, Gronchi A. Chordoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kaiser TE, Pritchard DJ, Unni KK. Clinicopathologic study of sacrococcygeal chordoma. Cancer. 1984;53:2574-2578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cody HS, Marcove RC, Quan SH. Malignant retrorectal tumors: 28 years’ experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:501-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Gray SW, Singhabhandhu B, Smith RA, Skandalakis JE. Sacrococcygeal chordoma: Report of a case and review of the literature. Surgery. 1975;78:573-582. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Nicholls J, Dozios RR. Surgery of the colon and rectum. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone 1997; . |