Published online Mar 28, 2015. doi: 10.5412/wjsp.v5.i1.1

Peer-review started: October 1, 2014

First decision: October 28, 2014

Revised: November 4, 2014

Accepted: December 16, 2014

Article in press: December 17, 2014

Published online: March 28, 2015

Processing time: 187 Days and 7.4 Hours

Transanal surgery has and continues to be well accepted for local excision of benign rectal disease not amenable to endoscopic resection. More recently, there has been increasing interest in applying transanal surgery to local resection of early malignant disease. In addition, some groups have started utilizing a transanal route in order to accomplish total mesorectal excision (TME) for more advanced rectal malignancies. We aim to review the role of various transanal and endoscopic techniques in the local resection of benign and malignant rectal disease based on published trial data. Preliminary data on the use of transanal platforms to accomplish TME will also be highlighted. For endoscopically unresectable rectal adenomas, transanal surgery remains a widely accepted method with minimal morbidity that avoids the downsides of a major abdomino-pelvic operation. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery and transanal minimally invasive surgery offer improved visualization and magnification, allowing for finer and more precise dissection of more proximal and larger rectal lesions without compromising patient outcome. Some studies have demonstrated efficacy in utilizing transanal platforms in the surgical management of early rectal malignancies in selected patients. There is an overall higher recurrence rate with transanal surgery with the concern that neither chemoradiation nor salvage surgery may compensate for previous approach and correct the inferior outcome. Application of transanal platforms to accomplish transanal TME in a natural orifice fashion are still in their infancy and currently should be considered experimental. The current data demonstrate that transanal surgery remains an excellent option in the surgical management of benign rectal disease. However, care should be used when selecting patients with malignant disease. The application of transanal platforms continues to evolve. While the new uses of transanal platforms in TME for more advanced rectal malignancy are exciting, it is important to remain cognizant and not sacrifice long term survival for short term decrease in morbidity and improved cosmesis.

Core tip: The review summarizes the technology advances and analyzes their impact on the validity of local transanal management of benign vs malignant rectal neoplasms. Current data demonstrate that transanal surgery remains an excellent option for benign disease. As transanal platforms continue to evolve, caution should be used when selecting patients with malignant disease. In view of the fact that the alternative of abdominal oncological procedures (laparoscopic, robotic, open) provide high cure rates, it is important to remain cognizant and not sacrifice long term survival for short term benefits (decrease in morbidity and improved cosmesis).

- Citation: Devaraj B, Kaiser AM. Impact of technology on indications and limitations for transanal surgical removal of rectal neoplasms. World J Surg Proced 2015; 5(1): 1-13

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2832/full/v5/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5412/wjsp.v5.i1.1

Rectal neoplasms are frequent and range from simple to highly complex conditions. Decision factors for their optimal management among others include the size and true axial and radial location of the lesion, the level of rectal wall and adjacent organ involvement, but most importantly, whether a definitively non-malignant (e.g., lipoma), a potentially malignant (adenomatous polyp, carcinoid), or a malignant process is suspected or confirmed. Particularly for more advanced and malignant lesions, the standard approach consists of an abdominal low anterior resection; depending on the proximity to the pelvic floor and sphincter complex, it includes a resection of the anus (abdomino-perineal resection) or allows for restoration of the intestinal continuity[1,2]. The advantage of the abdominal total mesorectal excision (TME) is that it assures a lymphadenectomy and-if done correctly-the removal of an intact mesorectal envelope (fascia propria) as the two most relevant factors to reduce the risk of local recurrences. The disadvantages, however, include the magnitude of the surgery as such, the length of recovery, the risk for an anastomotic leak, a not negligible probability to require a temporary or permanent ostomy, and a marked negative functional impact.

As communicated by Parks et al[3], conventional transanal excision (TAE) became a widely adopted surgical technique with minimal morbidity for the management of low rectal lesions. Criteria were defined to characterize lesions best suited for TAE: it should be < 3-4 cm in size/diameter, encompass less than 25%-40% of the circumference, be mobile, and be in reach of the finger/anoscope (i.e., no more than 6-8 cm from the anal verge)[1]. This latter aspect represented the biggest technical limitations of conventional transanal surgery, as mid to upper rectal tumors were out of reach secondary to inadequate exposure.

In more recent years, a number of technical developments have evolved to overcome these limitations. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEMS) and later transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) have allowed for local excision of tumors anywhere in the entire rectum. The improved reach and visualization allows for a finer and controlled dissection which made it possible for surgeons to push the limits of what can be accomplished via a transanal route. Resection of larger, more proximal adenomas encompassing more than 40% of the circumference have been carried out with low morbidity and acceptable recurrence rates for benign neoplasms[4-6].

Whether transanal surgery should be applied to malignant disease remains a matter of considerable debate. Even when limiting local excision to early tumors with favorable histology, as described by Willett et al[7], a significant rate of local recurrence has been reported[8-10]. Two factors are thought to contribute to this unfavorable outcome: (1) direct implantation of cancer cells into the surgical wound as a result of the direct instrumentation of the tumor; and (2) the lack of a lymphadenectomy even though 7%-10% of T1 tumors are found to have lymph node metastases[1,2]. This latter aspect not only leaves behind nodal tumor tissue, but results in understaging and hence undertreatment of stage III disease. Furthermore, salvage therapy after failure of local excision may involve more than what would have been needed initially and potentially require multivisceral resection with increased morbidity and lower overall survival[11,12].

Advances in endoscopy techniques have led to the introduction of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). This procedure has demonstrated some efficacy in the resection of larger (> 2 cm) and sessile lesions, characteristics that would have in the past ruled out the possibility of an endoscopic resection[13-16]. Similar to transanal surgery, EMR is not suited to perform a lymphadenectomy and carries a risk of bowel perforation with intraperitoneal bowel segments.

In recent years, some groups have extended the use of TEMS and TAMIS platforms in order to accomplish transanal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) TME[17,18]. In addition, a combination of the da Vinci robotic system (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, United States) with the TAMIS platform was used to carry out the first series of robotic-assisted transanal surgery for TME[19]. Experience with these approaches remain confined to specialty groups and limited to feasibility case reports[19-22].

The goal of this article is to highlight the various transanal surgical techniques and analyze the available evidence on the validity of local excision of benign and malignant rectal neoplasms.

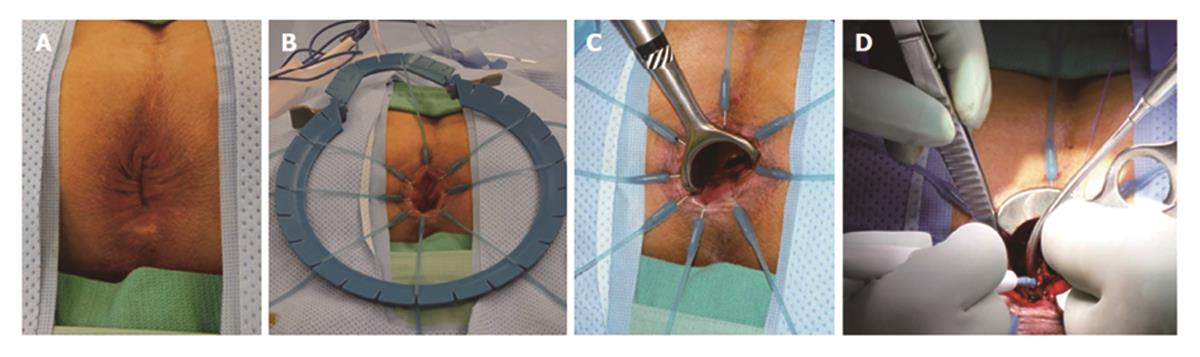

TAE can be performed with minimal specialty equipment, but depends on an optimized exposure of the target lesion as well as good hemostasis throughout the procedure. A variety of retractors are available, but in our hands, a Lone Star retractor (Coopersurgical, Inc. Trumbull, Connecticut, United States) to retract/evert the dentate line in combination with a handheld anal retractor has been the most reliable set-up (Figure 1). A circumferential margin of about 1cm is marked out by diathermy around the lesion. A full thickness excision using energy devices is then carried out whereby fragmentation of the specimen should be avoided. Fixation and orientation of the excised lesion on a wax board should then be carefully performed to prevent the tissue from rolling up and allow for proper pathological assessment of the resection margins (Figure 2). The defect should be washed out and either closed transversely with interrupted absorbable stitches or left open.

TAE overall is well tolerated and associated with only minor morbidity. However, there appears to be a significant variability in regards to recurrence rates after local excision of rectal adenomas ranging from 3%-40% in published series[23-26]. In a 10 year single institution review of 26 transanally excised adenomas, Hoth et al[27] reported a 38% recurrence rate over an average follow-up period of 25 mo. In a larger series of 117 patients with an average follow-up of 55 mo, Sakamoto et al[28] demonstrated an overall 30% recurrence rate for rectal adenomas. The authors postulated that the high recurrence rate was the result of inadequate exposure leading to incomplete excision[28]. A more recent and even larger study by Pigot et al[29] on a cohort of 207 patients undergoing TAE for rectal villous adenomata yielded better outcomes. The authors claimed to obtain improved intra-operative visualization by creating a cutaneo-mucus flap handle to allow for gentle traction, hence allowing for complete excision of the rectal adenoma with a recurrence rate of only 3.6%. Overall, the data on conventional TAE demonstrate higher than expected recurrence rates even for benign rectal adenomas; nonetheless, this surgical approach remains widely accepted for management of benign rectal pathologies in very distal location and close proximity to the sphincter structures.

Unquestionably, similarly high local recurrence rates would seem much more concerning in the management of malignant rectal tumors. Some 20 years ago, Willett et al[7] completed one of the earlier comparisons of standard resection with transanal local excision for low T1/T2 rectal cancer. This study was one of the first to suggest that in patients with favorable cancer histology (well differentiated, no venous or lymphovascular involvement), transanal surgery might be an acceptable alternative to standard resection. Fifty-six patients who had undergone transanal surgery were compared to 69 patients subjected to an abdomino-perineal resection (APR). Transanal surgery in 28 patients with favorable cancer histology resulted in a 5 year disease-free survival of 87% and a local control rate of 96%, whereas the other 28 patients with unfavorable cancer histology only achieved a 57% and 68%, respectively. In contrast, APR in 49 patients with favorable tumor histology resulted in 5 year disease-free survival and local control rates of 91% and 91%, compared to 79% and 89%, respectively, in 20 patients with unfavorable tumor histology.

Since then, several single institution case series have been published that compared transanal local excision to standard resection in T1 rectal cancers[30-33]. These results are summarized in Table 1. Overall, there is a significantly increased 5 year local recurrence rate with transanal surgery (7%-18%) compared to standard resection (0%-3%). The 5 year overall survival in the transanal local excision group was also noted to be substantially lower (72%-87%) than in the standard resection groups (80%-96%). The most recent of these studies by Nash et al[33] found a 20% incidence of lymph node metastasis in the standard resection group despite the tumor histological profile being similar between the 2 groups. This high prevalence of lymph node metastasis for early T tumors is about double the expected number from previously published reports[34-36]. At 7 years, cancer related deaths were 17% in the TAE group compared to 6% in patients undergoing a standard oncological resection. The differences in both local recurrence and 5 year overall survival were not only statistically significant but clinically alarming enough for the authors to conclude that transanal surgery even in early rectal cancer offered inferior oncological outcomes and should be restricted to patients that are unable to undergo standard resection[33].

In addition to single institution case series, national cancer registries have recently reported results comparing transanal surgery to standard resection[37-42]. These results are summarized in Table 2. Such registries have the benefit of a much larger sample size at the expense of a lack of detail and standardization (surgical techniques, data incorporation and surveillance protocols). Even though two of the studies included a mix of T1 and T2 rectal tumors in their analysis[38,41], there still appear to be higher than expected local recurrence rates for transanal surgery (5.1%-12.5%) compared to standard resection (1.4%-6.9%). Though not reaching statistical significance, there was a clear trend towards improved overall survival in patients undergoing standard resection (80%-93%) vs transanal surgery (70%-87%). An insufficiently analyzed factor contributing to the lower survival in the transanal excision group could be the inherent selection bias prevalent in registry data whereby patients might have been directed towards local excision if they had relevant comorbidities and limited operability.

| Ref. | Year | Follow-up (yr) | n | 5 yr local recurrence | 5 yr overall survival | |||

| TAE | SR | TAE | SR | TAE | SR | |||

| Endreseth et al[37] | 2005 | 2-8.1 | 35 | 256 | 12% | 6%1 | 70%1 | 80%1 |

| You et al[42] | 2007 | 6.3 | 601 | 493 | 12.5% | 6.9%1 | 77% | 82% |

| Ptok et al[40] | 2007 | 3.5 | 85 | 359 | 5.1%1 | 1.4%1 | 84% | 92% |

| 2Folkesson et al[38] | 2007 | NA | 256 | 1141 | 7% | 2%1 | 87% | 93% |

| Hazard et al[39] | 2009 | 3.9 | 573 | 3040 | NA | NA | 71% | 84% |

| 2Saraste et al[41] | 2013 | NA | 448 | 3246 | 11.2% | 2.9% | 81% | 92% |

While there is little doubt about the substantially increased local recurrence rates after transanal surgery compared to standard resection, a key question is whether these recurrences are salvageable with further surgical or adjuvant chemoradiation. Data on this topic are limited to single institution reviews[43]. Data from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center suggested that a substantial fraction of patients with local recurrences only could be managed with salvage surgery, but that only 30% of these were alive at 6 years[43]. In the most recent data analysis from MD Anderson Cancer Center over an 18 year period, You et al[44] demonstrated that recurrent rectal cancer (initial T1-T3 disease) appeared at a median interval of 1.9 years. The majority of patients (87%) were candidates to undergo salvage therapy with an R0 resection being attained in 80% of these patients. However, salvage therapy was associated significant morbidity: sphincter preservation was possible in only a third; a third underwent multi-visceral resection with a perioperative morbidity of 50%. In addition, 5 year overall survival after salvage therapy was significantly lower at 68% compared to the reported 80%-90% survival rate that should be expected in stage 1-2 rectal cancers. Earlier data from other institutions mirror the MD Anderson experience: all demonstrating lower 5 year overall survival in salvage therapy (53%-59%) despite attaining an R0 resection in most cases (79%-97%)[11,12,45].

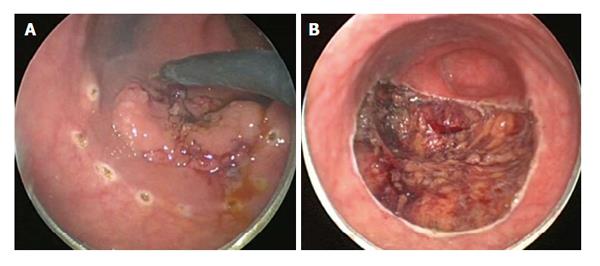

TEMS was originally developed by Buess et al[46] in Germany in the early 1980s. This transanal platform which is offered by different vendors includes video optics and an improved visibility due to creation of a pneumorectum (Figure 3). It consists of a 4 cm diameter proctoscope with a variable length of 7.5 to 20 cm allowing for visualization of the entire rectum. An airtight seal is maintained between the proctoscope and the anus allowing for pressure-controlled rectal insufflation with CO2. The faceplate of the proctoscope has 4 ports allowing for the insertion of the camera and three other working instruments (Figure 4). The ends of the operating instruments are angulated to improve their range of motion in the tight rectal space. The entire unit is fixed to the operating table and stabilized via an articulating arm. The procedure is facilitated by positioning the patient such that the target lesion is in the dependent position. Obstacles of this technology are its substantial initial cost to purchase the specialty equipment as well as a steep learning curve[47,48].

As with TAE, there is overall minimal perioperative morbidity associated with TEMS[49-51]. However, given the larger size of the operating proctoscope in relation to traditional handheld anal retractors, a negative impact (stretch injury) on the sphincter would not come as a surprise. In fact, some studies analyzed the effect of TEMS on anorectal function[52-57]; lower sphincter pressures were observed but the squeeze pressures ultimately improved by 1 year after TEMS[57]. Similarly, in study with a 5 year follow up after TEMS, Allaix et al[52] demonstrated a return of manometric values to pre-operative levels after 1 year. Utilizing sequential Fecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI) and Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life scores, Cataldo et al[53] and Doornebosch et al[54] did not note a decrease in either one after TEMS. The current evidence suggests that TEMS does not have any long lasting deleterious effect on anorectal function.

With the introduction of TEMS, larger and more proximal rectal adenomas are now amenable to local surgical excision. Local recurrence rates after adenoma excision by TEMS have been reported by numerous largely single institution studies (2.4%-16%)[58-71]. The results are summarized in Table 3. Even though the majority of studies did not strictly compare the two approaches, there appeared overall to be a lower recurrence rate of rectal adenomas excised via TEMS compared to TAE (3%-40%) as mentioned earlier. In addition, 2 other studies designed to pitch TEMS against conventional transanal surgery have also demonstrated lower recurrence rates with TEMS[58,64]. De Graaf et al[58] resected 216 adenomas via TEMS and 43 via TAE and found more frequent negative margins (88% vs 50%, P < 0.001) and lower recurrence rates (6.1% vs 28.7%, P < 0.001) in the TEMS group. Similarly, Moore et al[64] demonstrated a lesser degree of specimen fragmentation (94% vs 65%, P < 0.001) in addition to increased negative margins (90% vs 71%, P = 0.001) and lower recurrence rates (5% vs 27%, P = 0.004) with TEMS. Numerous factors come together and contribute to the better quality and outcomes parameters achieved with TEMS, such as improved operative visualization and magnification, increased stability and decreased need for specimen traction, optimized hemostasis, as well as improved instrumentation, all of which lead to increased completeness of the excision and decreased fragmentation of the specimen. Technical challenges are encountered with either higher lesions or very low lesions. In the upper rectum, the risk of perforation into the peritoneum is higher and particularly true for anterior lesions in female patients. On the other hand, very distal rectal polyps may represent a challenge insofar as the pneumorectum may be difficult to entertain. Furthermore, there is a risk of creating a rectovaginal fistula. Nonetheless, reported complication rates for TEMS are comparably low and range between 3%-15% and includes among others bleeding, infection, urinary retention; retroperitoneal tracking of air can frequently be seen but typically does not require any intervention. Even the majority of perforations into the peritoneum can be managed directly through the transanal approach, hence without a need for an abdominal intervention[62,71-74]. The available evidence suggests that TEMS for rectal adenomas not only avoids major abdominal procedures, but also is safe and achieves acceptable recurrence rates that are favorable compared to TAE.

| Ref. | Year | Follow-up (yr) | n | Recurrence |

| Said et al[67] | 1995 | 3.2 | 260 | 6.5% |

| Platell et al[65] | 2004 | 1.5 | 62 | 2.4% |

| Endreseth et al[60] | 2005 | 2 | 64 | 13% |

| Whitehouse et al[71] | 2006 | 3.3 | 143 | 4.8% |

| McCloud et al[63] | 2006 | 2.6 | 75 | 16% |

| Guerrieri et al[86] | 2008 | 3.7 | 588 | 4.3% |

| Speake et al[68] | 2008 | 1 | 80 | 12.5% |

| Moore et al[64] | 2008 | 1.7 | 40 | 3% |

| de Graaf et al[59] | 2009 | 2.3 | 309 | 6.6% |

| Ramirez et al[66] | 2009 | 3.6 | 149 | 5.4% |

| van den Broek et al[70] | 2009 | 1.1 | 248 | 9.3% |

| Guerrieri et al[61] | 2010 | 7 | 402 | 4% |

| Tsai et al[69] | 2010 | 2 | 156 | 5% |

| de Graaf et al[58] | 2011 | 2.7 | 208 | 6.1% |

Given the improved success with management of adenomas with TEMS compared to TAE, the next natural progression would be to ascertain if these results extended to malignant disease. Comparing TEMS to TAE in early rectal cancers (T1, T2), Christoforidis et al[75] noted significantly higher rates of negative margins with TEMS (98% vs 75%, P = 0.017). Although not reaching statistical significance, they also estimated 5 year recurrence rates to be lower (15.4% vs 29.1%, P = 0.108) and 5 year overall survival rates to be higher (79.9% vs 66%, P = 0.119) with TEMS. Similarly, Langer et al[76] also found lower recurrence rates with TEMS compared to TAE (10% vs 15%). The authors surmised that this was likely due to the overall lower rates of R1 resections that resulted from TEMS excision (19% vs 37%, P = 0.001).

Head to head comparisons of TEMS against standard resection for T1 rectal cancers have also been reported by various single institutions (Table 4)[77-81]. In general, the risk of recurrence after TEMS, although lower than after TAE, remains substantially higher compared to standard oncological resection. Results of data regarding salvage therapy for recurrent disease after TEMS are similar to that reported for TAE[82,83]. Sphincter preservation was improved (50%-70%) compared to TAE (33%)[44]; however, this difference might simply be accounted for by the more proximal location of the lesions excised in the TEMS group thus allowing for more salvage low anterior resections to be performed. Comparable to salvage therapy after TAE, perioperative morbidity was high at 50% and overall 3 year survival after salvage surgery was decreased[82].

| Ref. | Year | Follow-up (yr) | n | 5 yr local recurrence | 5 yr overall survival | |||

| TEMS | SR | TEMS (%) | SR (%) | TEMS (%) | SR (%) | |||

| Winde et al[81] | 1996 | 3.8[TEMS]/3.4[SR] | 24 | 26 | 4.2 | 0 | 96 | 96 |

| Heintz et al[78] | 1998 | 4.3 | 46 | 34 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 79 | 81 |

| Lee et al[79] | 2003 | 2.6[TEMS]/2.9[SR] | 52 | 22 | 4.1 | 0 | 100 | 92.9 |

| Palma et al[80] | 2009 | 7.2[TEMS]/7.8[SR] | 34 | 17 | 5.9 | 0 | 88.23 | 82.35 |

| De Graaf et al[77] | 2009 | 3.5[TEMS]/7[SR] | 80 | 75 | 241 | 01 | 75 | 77 |

For more advanced rectal cancer (T2 and above), significant local recurrence rates have been reported after either TAE or TEMS likewise[84-92]. Lee et al[79] reported a 5 year recurrence rate of 20% with TEMS compared to only 9% recurrence with standard resection of T2 rectal cancer. Similarly, the Minnesota experience on utilizing TEMS for T2 and T3 rectal cancers found recurrence rates of 23.5% and 100%, respectively[69]. As a result, some groups have incorporated the use of neoadjuvant chemo and radiation therapy (CRT) prior to TEMS excision in hopes of reducing the unacceptably high local recurrence rates in T2 rectal cancers. Lezoche et al[93] reported a substantially decreased local recurrence rate of 5.7% after neoadjuvant CRT and TEMS for T2 cancers. However, the recurrence rate was still double that of standard resection (2.8%). More recently, Marks et al[94] demonstrated a recurrence rate of 6.8% with TEMS compared to 0% in the standard resection arm after neoadjuvant CRT. The ACOSOG Z6041 trial, a prospective, multi-center phase-2 trial of neoadjuvant CRT and local excision for T2 rectal cancers recently reported its preliminary results[95]. The neoadjuvant protocol included treatment with capecitabine and oxaliplatin in addition to 50.4 Gy of external beam radiotherapy. Local excision via TAE or TEMS was performed 4 wk after completion of neoadjuvant CRT. At the price of substantial toxicity, 34 out of 77 patients completing the protocol (44%) showed a complete pathological response with overall 49 (64%) patient’s tumors being downstaged (ypT0-1). Four patients (5%) did progress to ypT3 tumors. Long term follow up on recurrence and overall survival rates are still pending. Furthermore, neoadjuvant CRT protocols will likely further undergo optimization to improve the adverse event profile. The current evidence suggests that local excision for more advanced rectal cancers (T2 and above) risks treatment understaging and leads to significant local recurrence. It should therefore be restricted to palliation of patients that are otherwise not able to undergo standard resection.

A different target for which TEMS has been increasingly used are rectal carcinoids. With growing numbers of colonoscopies being performed, a 10 fold increase in the incidence of rectal carcinoids has been noted in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and end results registry[96]. As a result, there has also been a substantial increase in the number of transanal surgical excisions of the incidental rectal carcinoids. General consensus guidelines for rectal carcinoids consider them amenable to transanal excision include if they are well differentiated, no more than 2 cm in size, are confined to the submucosa and show no lymphovascular invasion[97]. The majority of published data on rectal carcinoids have utilized the TEMS platform as the approach to carry out the transanal excision[98-103]. Kumar et al[102] in a review of 24 patients who underwent TEMS excision of rectal carcinoids demonstrated no recurrence. Kinoshita et al[100] reported no recurrence or carcinoid-specific mortality after TEMS excision in 27 patients over a follow-up period of 70.6 mo. Likewise, Ishikawa et al[99] found no recurrence when rectal carcinoids were excised by either TEMS or conventional transanal surgery after a mean follow-up of 2 years. However, the analysis of 202 patients with rectal carcinoids surprisingly found that up to 30% of carcinoid tumors > 1 cm harbored nodal disease (OR = 32.7, P = 0.006), with lymphovascular invasion being an additional independent risk factor for nodal disease (OR = 19.6, P < 0.001)[104]. Despite the limitations of the data and generally rather small cohorts, it appears that transanal excision either by conventional approach or TEMS is appropriate to tumor sizes up to 1 cm.

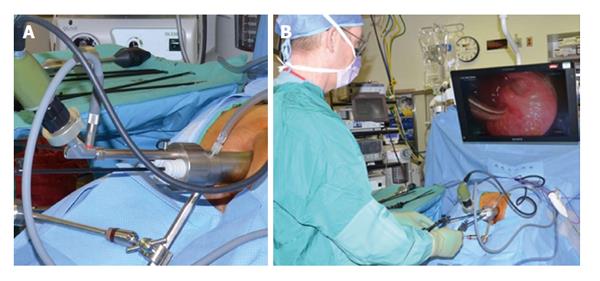

TAMIS was “accidentally” reported in 2009 and quickly gained attention as a cheap and easily available alternative to the TEMS[105]. A SILS port (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States) was used in the beginning. Subsequently, specifically designed single-use transanal port systems (GelPOINT Path, Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, United States) were developed and made commercially available. The GELPOINT path platform is about 44 mm long with a diameter of 34 mm and was specifically designed for TAMIS. The TAMIS port should sit on the levator ani muscles just above the puborectalis. The port is then optionally secured in place with sutures. Usually, 3 working ports are placed into the GelPOINT path: 2 working instruments and a laparoscopic 5 mm camera. As in TEMS, a seal is created between the anus and the TAMIS port allowing for distention of the rectum with CO2 insufflation. Unlike TEMS, the camera position is not fixed and the TAMIS port is shorter and not angled at the end: this enables an increased working angle allowing for potentially near/circumferential excision without having to re-position the patient. No specialty laparoscopic instruments are required. However, there some potential drawbacks: The stability of the transanal platform is overall reduced given that there is no stabilizing arm to dock onto. In addition, the laparoscopic camera generally has to be removed quite often and cleaned. To combat this, the use of an endoscope has been employed[106].

Like for TAE and TEMS, morbidity associated with TAMIS has been minimal[105,107-109]. Schiphorst et al[109], over a median short term follow-up of 11 mo, recently reported comparable anorectal function based on FISI scores to TEMS after TAMIS.

Given the relatively short interval since TAMIS inception, the majority of data on TAMIS - related the excision of rectal neoplasms is limited to small cohort single institution studies and case reports. A comprehensive review of the TAMIS experience from 2010-2013 was recently published by Martin-Perez et al[5]. The authors reported an overall margin positivity rate of 4.36% (12/275). Local recurrence was 2.7% (7/259) on short term follow-up (mean 7.1 mo). Conversion was only 2.3% (9/390) with a 1.025% (4/390) rate of unintended entry to the peritoneal cavity. In the largest published single institution series, Albert et al[107] resected 25 rectal adenomas, 23 malignancies (1 TIS, 16 T1, 3 T2, 3 T3) and 2 neuroendocrine tumors. The authors reported a 94% negative margin rate (47/50) with 4% (2/50) specimen fragmentation. Over a median of 20 mo follow-up, a local recurrence rate of 4% (2/50) was reported. Overall, the preliminary data showed that TAMIS achieved results comparable to TEMS in terms of recurrence rates and morbidity. Head to head comparisons in prospective studies with more long term follow up data are needed before any final recommendation can be made on the preferred transanal platform for local excision.

In recent years, application of EMR has led to more aggressive endoscopic resection of rectal adenomas and even early rectal cancers in specialized centers. The technique involves circumferentially marking the resection margin as done in transanal surgery. A submucosal injection of mixture of dye, saline and diluted epinephrine is performed to accomplish lifting of the lesion away from the underlying tissue. In some instances, magnification or chromoendoscopy can help further elucidate the true edges of a rectal lesion. Snare excision with cautery is performed whereby lesions < 2 cm are usually resected en bloc, while larger lesions may require several separate excisions. Reported complications include bleeding, post polypectomy syndrome and perforation, the vast majority of which resolve conservatively or require application of endoscopic clips for resolution[110-112].

In an earlier prospective study on use of EMR in resection of rectal adenomas, Hurlstone et al[113] resected 62 rectal adenomas (4 T1 cancers, 58 adenomas). The 3 mo local recurrence rate was 8% (5/62): 4 patients underwent repeat EMR and 1 patient had a low anterior resection. After a median follow-up of 14 mo, they noted that 98% (61/62) of the cohort remained free of recurrence. Main complication was bleeding (8%) that was managed with an endoclip placement. Based on this, the authors suggested that EMR for rectal adenomas and early rectal cancers is safe and effective.

More recently, Arezzo et al[114] completed a meta-analysis comparing EMR to TEMS in the resection of large rectal lesions. Eleven EMR and 10 TEMS studies involving 2077 patients were included for review. En bloc resection rates were 87.8% (CI: 84.3-90.6) for EMR compared to 98.7% (CI: 97.4-99.3) for TEMS. This corresponded to a substantially reduced R0 resection percentage for EMR vs TEMS (74.6% vs 88.5%, P < 0.001). Interestingly, recurrence rates were lower in the EMR group (2.6% vs 5.2%, P < 0.001). However, this difference could be explained by the significantly longer length of follow-up in the TEMS arm (mean 58.9 mo vs 6-12 mo). Even though there was a lower recurrence rate in the EMR group, a larger percentage of EMR patients eventually required standard resection (8.4% vs 1.8%, P < 0.001). Morbidity was similar at 8% in both groups.

In summary, the available data demonstrate that while feasible, EMR for rectal lesions appears to have poorer results compared to TEMS. No data comparing TAMIS to EMR is available at present, but it seems reasonable to expect similar results given the overall comparability of results obtained between TEMS and TAMIS thus far.

Expanding on the principles of NOTES, preliminary case series reported utilizing the transanal route to accomplish TME. An updated assessment of the transanal NOTES experience by Emhoff et al[18] included a total of 72 cases where a complete TME excision with largely negative circumferential margins could be obtained. The overall intraoperative and postoperative complication rate was 8.3% and 27.8%, respectively. There was a 2.8% incidence of conversion to open surgery with no 30 d mortality. No recurrence was reported but follow-up periods were generally limited to a few months only. Furthermore, there was an inherent patient selection bias with the majority of patients having early rectal cancer (T1, T2), low body mass indexs (BMIs), non-recurrent tumors and no previous history of pelvic surgery. Of the 10 case series reviewed, only 1 study by Rouanet et al[115] included higher risk patients (BMI > 30, narrow pelvis, T3/T4, recurrent and large tumors) with longer follow-up (median 21 mo). Not surprisingly, the results were less favorable: negative margin rates were lower (87% vs 95%) compared to lower risk patients in the other studies. Distant disease was noted in 8 patients (26.7%) and local recurrence occurred in 4 patients (13.3%). Overall survival was only 80.5% at 2 years. A 20 patient experience utilizing the TAMIS platform to achieve a TME were comparable to those by Emhoff et al[18]: 90% negative margin, 85% complete/near complete TME, and a 5% recurrence rate over median follow-up of 6 mo[17].

Transanal/TAMIS TME are techniques still in their infancy. The current data are limited to single institution cases series and lack a control arm. In addition, functional data are extremely limited with regard to the colo-anal anastomoses that generally ensues from the transanal/TAMIS TME. Data from randomized controlled studies with long term follow-up will ultimately be needed to determine if this new approach to TME is truly needed and should be adopted on a more universal level.

Transanal surgery has undergone significant technical advances in the last 25 years. The onset of improved video and computer technology and the onset of laparoscopic surgery in general have undoubtedly contributed to the evolution of this field. Conventional TAE remains a widely accepted approach in the management of low rectal adenomas. However, the transanal platforms of TEMS and TAMIS offer improved visualization, reach and allow for a finer and better controlled dissection in the limited rectal space. This likely explains the overall lower recurrence rates observed in the TEMS-/TAMIS-assisted local resection of benign rectal tumors. EMR for rectal lesions, while feasible, requires considerable technical expertise and more importantly offers inferior results compared to transanal or laparoscopic resective surgery. Based on the available evidence, local excision of rectal adenomas (which by definition are limited to the mucosa) is safe technique affording low morbidity without compromising patient outcome.

Data surrounding transanal excision of rectal malignancies remain more of a mixed baggage because the local excision does not achieve a lymphadenectomy and risk implanting malignant cells into the surgical wound. Small size (1 cm or less) rectal carcinoids appear to be amenable to local resection without any long term increase risks of recurrence. However, local recurrence rates of even early rectal adenocarcinoma unquestionably are higher than with a standard oncological resection and cannot reliably be improved with (neo-)adjuvant chemoradiation without substantial morbidity. Salvage therapy after local failure is not always possible but is usually associated with high perioperative morbidity and lower overall long term survival.

The true philosophical question a surgeon should not only ask the patient but also him-/herself is whether vanity and fear from an abdominal surgery, its scars, or a potential stoma are sufficient reason to jeopardize the chances to cure an early cancer (stage I) which by all means should have a > 90% of disease-free survival. A wealth of data in the literature has supported the use of laparoscopic surgery in particular for mid and high rectal tumors, not to speak of any colon tumors. Intermediate and long term outcomes from various randomized controlled trials from Europe and Asia (CLASICC, COLOR II, COREAN) have demonstrated non-inferiority of laparoscopic surgery compared to traditional open surgery for rectal cancer in regards to completeness of the resection, lymph node harvest, local recurrence rates, and overall survival. In addition, the laparoscopic approach has consistently been associated with shorter length of stay and reduced time to bowel function recovery[116-118]. Even for low tumors, the laparoscopic or robotic approach allows for a sphincter-preserving complete mesorectal excision and colo-anal anastomosis in the overwhelming majority of cases with excellent oncological and acceptable functional outcomes, and with no local recurrence noted for early rectal cancers[119-121]. It therefore seems not justifiable to risk an incomplete excision or seeding the operative field with cancer cells, which in the case of a TAMIS/TME would come to be located right on the freed presacral fascia, pelvic side wall, or the free peritoneal cavity. An unbiased discussion highlighting the risks and benefits of transanal surgery with the patient should assure to make the best informed decision in the setting of rectal adenocarcinoma. Appropriate use of an excellent technology should include self-restriction to define the best selection of pathologies and patients (Table 5). In cases where the diagnosis and/or stage are uncertain, the transanal local excision can be used as excisional biopsies (potentially limited to the mucosa only to avoid distortion of the mesorectum), but final judgment on the appropriateness of the transanal approach as opposed to the ultimate best treatment should be reserved until the definitive pathology report has been obtained. If more treatment should be needed, it might-for concerns of postsurgical tissue changes-be desirable to postpone it for 4-6 wk.

| Category | Primary approach | Secondary or individualized approach |

| Benign pathology | Low rectum: TAE or TEMS Middle to high rectum: TEMS/TAMIS/EMR or LAR Proximal to rectum: EMR or L/O CR | Very large lesion: LAR |

| Borderline pathology | Carcinoid < 1 cm with favorable features: TEMS/TAMIS Scar after colonoscopic removal of cancerous polyp: TEMS/TAMIS Uncertain dignity: TEMS/TAMIS mucosal resection as excisional biopsy | Excisional biopsy with TEMS/TAMIS/TAE → LAR if malignant? |

| Malignant (Rectum) | u/pT1: LAR u/pT2: LAR u/pT3: CRT + LAR Recurrence: CRT + LAR Carcinoid > 1 cm: LAR | u/pT1 + morbidity: TAE/TEMS/TAMIS u/pT2: TAE/TEMS/TAMIS + CRT |

| Malignant (Colon) | pTis: EMR/polypectomy pT1: L/O CR (unless free stalk > 2 mm) > T1: L/O CR | pTis (large): L/O CR pT1 + morbidity: EMR + observation |

P- Reviewer: Brisinda G, Djodjevic I, Piccinni G, Stanojevic GZ

S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Monson JR, Weiser MR, Buie WD, Chang GJ, Rafferty JF, Buie WD, Rafferty J; Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal. Practice parameters for the management of rectal cancer (revised). Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:535-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kaiser AM. McGraw-Hill Manual Colorectal Surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill 2009; . |

| 3. | Parks AG, Stuart AE. The management of villous tumours of the large bowel. Br J Surg. 1973;60:688-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bretagnol F, Merrie A, George B, Warren BF, Mortensen NJ. Local excision of rectal tumours by transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Br J Surg. 2007;94:627-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Martin-Perez B, Andrade-Ribeiro GD, Hunter L, Atallah S. A systematic review of transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) from 2010 to 2013. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:775-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zacharakis E, Freilich S, Rekhraj S, Athanasiou T, Paraskeva P, Ziprin P, Darzi A. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal tumors: the St. Mary’s experience. Am J Surg. 2007;194:694-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Willett CG, Compton CC, Shellito PC, Efird JT. Selection factors for local excision or abdominoperineal resection of early stage rectal cancer. Cancer. 1994;73:2716-2720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Heidary B, Phang TP, Raval MJ, Brown CJ. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a review. Can J Surg. 2014;57:127-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Smart CJ, Cunningham C, Bach SP. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:143-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | You YN. Local excision: is it an adequate substitute for radical resection in T1/T2 patients? Semin Radiat Oncol. 2011;21:178-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Friel CM, Cromwell JW, Marra C, Madoff RD, Rothenberger DA, Garcia-Aguílar J. Salvage radical surgery after failed local excision for early rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:875-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Weiser MR, Landmann RG, Wong WD, Shia J, Guillem JG, Temple LK, Minsky BD, Cohen AM, Paty PB. Surgical salvage of recurrent rectal cancer after transanal excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1169-1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Higaki S, Hashimoto S, Harada K, Nohara H, Saito Y, Gondo T, Okita K. Long-term follow-up of large flat colorectal tumors resected endoscopically. Endoscopy. 2003;35:845-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hurlstone DP, Sanders DS, Cross SS, Adam I, Shorthouse AJ, Brown S, Drew K, Lobo AJ. Colonoscopic resection of lateral spreading tumours: a prospective analysis of endoscopic mucosal resection. Gut. 2004;53:1334-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kudo S, Kashida H, Tamura T, Kogure E, Imai Y, Yamano H, Hart AR. Colonoscopic diagnosis and management of nonpolypoid early colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2000;24:1081-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hurlstone DP, Cross SS, Lobo AJ. High-magnification chromoscopic ileoscopy in familial adenomatous polyposis: detection in vivo of colonic metaplasia and microadenoma formation. Endoscopy. 2004;36:194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Atallah S, Martin-Perez B, Albert M, deBeche-Adams T, Nassif G, Hunter L, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery for total mesorectal excision (TAMIS-TME): results and experience with the first 20 patients undergoing curative-intent rectal cancer surgery at a single institution. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:473-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Emhoff IA, Lee GC, Sylla P. Transanal colorectal resection using natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 1:29-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Atallah S, Nassif G, Polavarapu H, deBeche-Adams T, Ouyang J, Albert M, Larach S. Robotic-assisted transanal surgery for total mesorectal excision (RATS-TME): a description of a novel surgical approach with video demonstration. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:441-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bardakcioglu O. Robotic transanal access surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1407-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Buchs NC, Pugin F, Volonte F, Hagen ME, Morel P, Ris F. Robotic transanal endoscopic microsurgery: technical details for the lateral approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1194-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Atallah S, Martin-Perez B, Pinan J, Quinteros F, Schoonyoung H, Albert M, Larach S. Robotic transanal total mesorectal excision: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:1047-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chiu YS, Spencer RJ. Villous lesions of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1978;21:493-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nivatvongs S, Balcos EG, Schottler JL, Goldberg SM. Surgical management of large villous tumors of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1973;16:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nivatvongs S, Nicholson JD, Rothenberger DA, Balcos EG, Christenson CE, Nemer FD, Schottler JL, Goldberg SM. Villous adenomas of the rectum: the accuracy of clinical assessment. Surgery. 1980;87:549-551. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Thomson JP. Treatment of sessile villous and tubulovillous adenomas of the rectum: experience of St. Mark’s Hospital. 1963-1972. Dis Colon Rectum. 1977;20:467-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hoth JJ, Waters GS, Pennell TC. Results of local excision of benign and malignant rectal lesions. Am Surg. 2000;66:1099-1103. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Sakamoto GD, MacKeigan JM, Senagore AJ. Transanal excision of large, rectal villous adenomas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:880-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pigot F, Bouchard D, Mortaji M, Castinel A, Juguet F, Chaume JC, Faivre J. Local excision of large rectal villous adenomas: long-term results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1345-1350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bentrem DJ, Okabe S, Wong WD, Guillem JG, Weiser MR, Temple LK, Ben-Porat LS, Minsky BD, Cohen AM, Paty PB. T1 adenocarcinoma of the rectum: transanal excision or radical surgery? Ann Surg. 2005;242:472-477; discussion 477-479. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Mellgren A, Sirivongs P, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD, García-Aguilar J. Is local excision adequate therapy for early rectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1064-1071; discussion 1071-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nascimbeni R, Nivatvongs S, Larson DR, Burgart LJ. Long-term survival after local excision for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1773-1779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nash GM, Weiser MR, Guillem JG, Temple LK, Shia J, Gonen M, Wong WD, Paty PB. Long-term survival after transanal excision of T1 rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:577-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chang HC, Huang SC, Chen JS, Tang R, Changchien CR, Chiang JM, Yeh CY, Hsieh PS, Tsai WS, Hung HY. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in pT1 and pT2 rectal cancer: a single-institute experience in 943 patients and literature review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2477-2484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kobayashi H, Sugihara K. Surgical management and chemoradiotherapy of T1 rectal cancer. Dig Endosc. 2013;25 Suppl 2:11-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Saraste D, Gunnarsson U, Janson M. Predicting lymph node metastases in early rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1104-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Endreseth BH, Myrvold HE, Romundstad P, Hestvik UE, Bjerkeset T, Wibe A. Transanal excision vs. major surgery for T1 rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1380-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Folkesson J, Johansson R, Påhlman L, Gunnarsson U. Population-based study of local surgery for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1421-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hazard LJ, Shrieve DC, Sklow B, Pappas L, Boucher KM. Local Excision vs. Radical Resection in T1-2 Rectal Carcinoma: Results of a Study From the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Registry Data. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2009;3:105-114. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Ptok H, Marusch F, Meyer F, Schubert D, Koeckerling F, Gastinger I, Lippert H. Oncological outcome of local vs radical resection of low-risk pT1 rectal cancer. Arch Surg. 2007;142:649-655; discussion 656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Saraste D, Gunnarsson U, Janson M. Local excision in early rectal cancer-outcome worse than expected: a population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:634-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | You YN, Baxter NN, Stewart A, Nelson H. Is the increasing rate of local excision for stage I rectal cancer in the United States justified?: a nationwide cohort study from the National Cancer Database. Ann Surg. 2007;245:726-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Paty PB, Nash GM, Baron P, Zakowski M, Minsky BD, Blumberg D, Nathanson DR, Guillem JG, Enker WE, Cohen AM. Long-term results of local excision for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2002;236:522-529; discussion 529-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | You YN, Roses RE, Chang GJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Feig BW, Slack R, Nguyen S, Skibber JM. Multimodality salvage of recurrent disease after local excision for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1213-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Baron PL, Enker WE, Zakowski MF, Urmacher C. Immediate vs. salvage resection after local treatment for early rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:177-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Buess G, Theiss R, Hutterer F, Pichlmaier H, Pelz C, Holfeld T, Said S, Isselhard W. [Transanal endoscopic surgery of the rectum - testing a new method in animal experiments]. Leber Magen Darm. 1983;13:73-77. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Cataldo PA. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:915-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Papagrigoriadis S. Transanal endoscopic micro-surgery (TEMS) for the management of large or sessile rectal adenomas: a review of the technique and indications. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2006;3:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Darwood RJ, Wheeler JM, Borley NR. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is a safe and reliable technique even for complex rectal lesions. Br J Surg. 2008;95:915-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Maslekar S, Beral DL, White TJ, Pillinger SH, Monson JR. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: where are we now? Dig Surg. 2006;23:12-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Morino M, Allaix ME. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: what indications in 2013? Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:75-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Allaix ME, Rebecchi F, Giaccone C, Mistrangelo M, Morino M. Long-term functional results and quality of life after transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1635-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Cataldo PA, O’Brien S, Osler T. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a prospective evaluation of functional results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1366-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Doornebosch PG, Gosselink MP, Neijenhuis PA, Schouten WR, Tollenaar RA, de Graaf EJ. Impact of transanal endoscopic microsurgery on functional outcome and quality of life. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:709-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Herman RM, Richter P, Walega P, Popiela T. Anorectal sphincter function and rectal barostat study in patients following transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:370-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Kennedy ML, Lubowski DZ, King DW. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery excision: is anorectal function compromised? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:601-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Kreis ME, Jehle EC, Haug V, Manncke K, Buess GF, Becker HD, Starlinger MJ. Functional results after transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1116-1121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | de Graaf EJ, Burger JW, van Ijsseldijk AL, Tetteroo GW, Dawson I, Hop WC. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is superior to transanal excision of rectal adenomas. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:762-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | de Graaf EJ, Doornebosch PG, Tetteroo GW, Geldof H, Hop WC. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is feasible for adenomas throughout the entire rectum: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1107-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Endreseth BH, Wibe A, Svinsås M, Mårvik R, Myrvold HE. Postoperative morbidity and recurrence after local excision of rectal adenomas and rectal cancer by transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Guerrieri M, Baldarelli M, de Sanctis A, Campagnacci R, Rimini M, Lezoche E. Treatment of rectal adenomas by transanal endoscopic microsurgery: 15 years’ experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:445-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Guerrieri M, Baldarelli M, Morino M, Trompetto M, Da Rold A, Selmi I, Allaix ME, Lezoche G, Lezoche E. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery in rectal adenomas: experience of six Italian centres. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | McCloud JM, Waymont N, Pahwa N, Varghese P, Richards C, Jameson JS, Scott AN. Factors predicting early recurrence after transanal endoscopic microsurgery excision for rectal adenoma. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:581-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Moore JS, Cataldo PA, Osler T, Hyman NH. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is more effective than traditional transanal excision for resection of rectal masses. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1026-1030; discussion 1030-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Platell C, Denholm E, Makin G. Efficacy of transanal endoscopic microsurgery in the management of rectal polyps. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:767-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Ramirez JM, Aguilella V, Gracia JA, Ortego J, Escudero P, Valencia J, Esco R, Martinez M. Local full-thickness excision as first line treatment for sessile rectal adenomas: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2009;249:225-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Said S, Stippel D. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery in large, sessile adenomas of the rectum. A 10-year experience. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:1106-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Speake D, Lees N, McMahon RF, Hill J. Who should be followed up after transanal endoscopic resection of rectal tumours? Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:330-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Tsai BM, Finne CO, Nordenstam JF, Christoforidis D, Madoff RD, Mellgren A. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery resection of rectal tumors: outcomes and recommendations. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | van den Broek FJ, de Graaf EJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Reitsma JB, Haringsma J, Timmer R, Weusten BL, Gerhards MF, Consten EC, Schwartz MP. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery versus endoscopic mucosal resection for large rectal adenomas (TREND-study). BMC Surg. 2009;9:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Whitehouse PA, Tilney HS, Armitage JN, Simson JN. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: risk factors for local recurrence of benign rectal adenomas. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:795-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Allaix ME, Arezzo A, Arolfo S, Caldart M, Rebecchi F, Morino M. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal neoplasms. How I do it. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:586-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Kumar AS, Coralic J, Kelleher DC, Sidani S, Kolli K, Smith LE. Complications of transanal endoscopic microsurgery are rare and minor: a single institution’s analysis and comparison to existing data. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:295-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Seman M, Bretagnol F, Guedj N, Maggiori L, Ferron M, Panis Y. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) for rectal tumor: the first French single-center experience. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:488-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Christoforidis D, Cho HM, Dixon MR, Mellgren AF, Madoff RD, Finne CO. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery versus conventional transanal excision for patients with early rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2009;249:776-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Langer C, Liersch T, Süss M, Siemer A, Markus P, Ghadimi BM, Füzesi L, Becker H. Surgical cure for early rectal carcinoma and large adenoma: transanal endoscopic microsurgery (using ultrasound or electrosurgery) compared to conventional local and radical resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:222-229. [PubMed] |

| 77. | De Graaf EJ, Doornebosch PG, Tollenaar RA, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg E, de Boer AC, Bekkering FC, van de Velde CJ. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery versus total mesorectal excision of T1 rectal adenocarcinomas with curative intention. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1280-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Heintz A, Mörschel M, Junginger T. Comparison of results after transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical resection for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1145-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Lee W, Lee D, Choi S, Chun H. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical surgery for T1 and T2 rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1283-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Palma P, Horisberger K, Joos A, Rothenhoefer S, Willeke F, Post S. Local excision of early rectal cancer: is transanal endoscopic microsurgery an alternative to radical surgery? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:172-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Winde G, Nottberg H, Keller R, Schmid KW, Bünte H. Surgical cure for early rectal carcinomas (T1). Transanal endoscopic microsurgery vs. anterior resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:969-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Doornebosch PG, Ferenschild FT, de Wilt JH, Dawson I, Tetteroo GW, de Graaf EJ. Treatment of recurrence after transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) for T1 rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1234-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Hermsen PE, Nonner J, De Graaf EJ, Doornebosch PG. Recurrences after transanal excision or transanal endoscopic microsurgery of T1 rectal cancer. Minerva Chir. 2010;65:213-223. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Bleday R, Breen E, Jessup JM, Burgess A, Sentovich SM, Steele G. Prospective evaluation of local excision for small rectal cancers. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:388-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Garcia-Aguilar J, Mellgren A, Sirivongs P, Buie D, Madoff RD, Rothenberger DA. Local excision of rectal cancer without adjuvant therapy: a word of caution. Ann Surg. 2000;231:345-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Guerrieri M, Baldarelli M, Organetti L, Grillo Ruggeri F, Mantello G, Bartolacci S, Lezoche E. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for the treatment of selected patients with distal rectal cancer: 15 years experience. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2030-2035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Kim CJ, Yeatman TJ, Coppola D, Trotti A, Williams B, Barthel JS, Dinwoodie W, Karl RC, Marcet J. Local excision of T2 and T3 rectal cancers after downstaging chemoradiation. Ann Surg. 2001;234:352-358; discussion 358-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Lezoche E, Guerrieri M, Paganini AM, Baldarelli M, De Sanctis A, Lezoche G. Long-term results in patients with T2-3 N0 distal rectal cancer undergoing radiotherapy before transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1546-1552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Nastro P, Beral D, Hartley J, Monson JR. Local excision of rectal cancer: review of literature. Dig Surg. 2005;22:6-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Sengupta S, Tjandra JJ. Local excision of rectal cancer: what is the evidence? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1345-1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Stipa F, Lucandri G, Ferri M, Casula G, Ziparo V. Local excision of rectal cancer with transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM). Anticancer Res. 2004;24:1167-1172. [PubMed] |

| 92. | Varma MG, Rogers SJ, Schrock TR, Welton ML. Local excision of rectal carcinoma. Arch Surg. 1999;134:863-867; discussion 867-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Lezoche G, Baldarelli M, Guerrieri M, Paganini AM, De Sanctis A, Bartolacci S, Lezoche E. A prospective randomized study with a 5-year minimum follow-up evaluation of transanal endoscopic microsurgery versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision after neoadjuvant therapy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:352-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Marks J, Nassif G, Schoonyoung H, DeNittis A, Zeger E, Mohiuddin M, Marks G. Sphincter-sparing surgery for adenocarcinoma of the distal 3 cm of the true rectum: results after neoadjuvant therapy and minimally invasive radical surgery or local excision. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4469-4477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Garcia-Aguilar J, Shi Q, Thomas CR, Chan E, Cataldo P, Marcet J, Medich D, Pigazzi A, Oommen S, Posner MC. A phase II trial of neoadjuvant chemoradiation and local excision for T2N0 rectal cancer: preliminary results of the ACOSOG Z6041 trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:384-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Scherübl H. Rectal carcinoids are on the rise: early detection by screening endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:162-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Ramage JK, Goretzki PE, Manfredi R, Komminoth P, Ferone D, Hyrdel R, Kaltsas G, Kelestimur F, Kvols L, Scoazec JY. Consensus guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine tumours: well-differentiated colon and rectum tumour/carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Araki Y, Isomoto H, Shirouzu K. Clinical efficacy of video-assisted gasless transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) for rectal carcinoid tumor. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:402-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Ishikawa K, Arita T, Shimoda K, Hagino Y, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Usefulness of transanal endoscopic surgery for carcinoid tumor in the upper and middle rectum. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1151-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Kinoshita T, Kanehira E, Omura K, Tomori T, Yamada H. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery in the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumor. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:970-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Kobayashi K, Katsumata T, Yoshizawa S, Sada M, Igarashi M, Saigenji K, Otani Y. Indications of endoscopic polypectomy for rectal carcinoid tumors and clinical usefulness of endoscopic ultrasonography. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:285-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Kumar AS, Sidani SM, Kolli K, Stahl TJ, Ayscue JM, Fitzgerald JF, Smith LE. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal carcinoids: the largest reported United States experience. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:562-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Nakagoe T, Ishikawa H, Sawai T, Tsuji T, Jibiki M, Nanashima A, Yamaguchi H, Yasutake T. Gasless, video endoscopic transanal excision for carcinoid and laterally spreading tumors of the rectum. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1298-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Shields CJ, Tiret E, Winter DC. Carcinoid tumors of the rectum: a multi-institutional international collaboration. Ann Surg. 2010;252:750-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Atallah S, Albert M, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery: a giant leap forward. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2200-2205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | McLemore EC, Coker A, Jacobsen G, Talamini MA, Horgan S. eTAMIS: endoscopic visualization for transanal minimally invasive surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1842-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Albert MR, Atallah SB, deBeche-Adams TC, Izfar S, Larach SW. Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) for local excision of benign neoplasms and early-stage rectal cancer: efficacy and outcomes in the first 50 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:301-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Khoo RE. Transanal excision of a rectal adenoma using single-access laparoscopic port. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1078-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Schiphorst AH, Langenhoff BS, Maring J, Pronk A, Zimmerman DD. Transanal minimally invasive surgery: initial experience and short-term functional results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:927-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Poppers DM, Haber GB. Endoscopic mucosal resection of colonic lesions: current applications and future prospects. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:687-705, x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Kudo S, Rubio CA, Teixeira CR, Kashida H, Kogure E. Pit pattern in colorectal neoplasia: endoscopic magnifying view. Endoscopy. 2001;33:367-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Tamegai Y, Saito Y, Masaki N, Hinohara C, Oshima T, Kogure E, Liu Y, Uemura N, Saito K. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: a safe technique for colorectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2007;39:418-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Hurlstone DP, Sanders DS, Cross SS, George R, Shorthouse AJ, Brown S. A prospective analysis of extended endoscopic mucosal resection for large rectal villous adenomas: an alternative technique to transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:339-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Arezzo A, Passera R, Saito Y, Sakamoto T, Kobayashi N, Sakamoto N, Yoshida N, Naito Y, Fujishiro M, Niimi K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus transanal endoscopic microsurgery for large noninvasive rectal lesions. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:427-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Rouanet P, Mourregot A, Azar CC, Carrere S, Gutowski M, Quenet F, Saint-Aubert B, Colombo PE. Transanal endoscopic proctectomy: an innovative procedure for difficult resection of rectal tumors in men with narrow pelvis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:408-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Green BL, Marshall HC, Collinson F, Quirke P, Guillou P, Jayne DG, Brown JM. Long-term follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of conventional versus laparoscopically assisted resection in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, Fürst A, Lacy AM, Hop WC, Bonjer HJ. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:210-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1030] [Cited by in RCA: 1213] [Article Influence: 101.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |