Copyright

©The Author(s) 2015.

World J Surg Proced. Mar 28, 2015; 5(1): 1-13

Published online Mar 28, 2015. doi: 10.5412/wjsp.v5.i1.1

Published online Mar 28, 2015. doi: 10.5412/wjsp.v5.i1.1

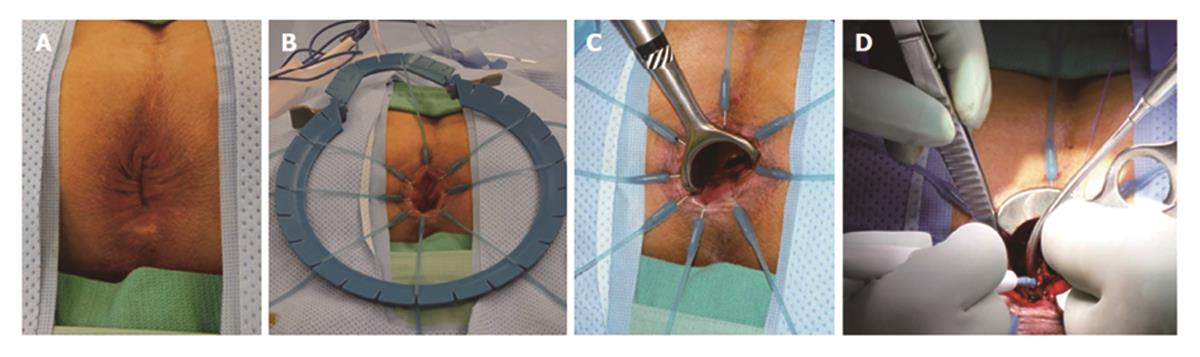

Figure 1 Conventional transanal excision with the patient in prone-jackknife position.

A: Anus at beginning of the surgery; B: Placement of Lone Star retractor; C: Additional hand-held retractor optimizes exposure; D: Direct transanal instrumentation under regular view.

Figure 2 Fixation and orientation of the specimen on a wax board.

The tissue is pinned down with needles. L(eft), R(ight), D(istal), and P(roximal) are carved into the wax. The specimen is subsequently placed in formalin for at least 24 h before processing and sectioning it onto slides.

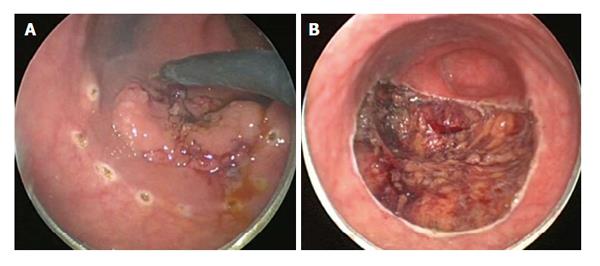

Figure 3 Transanal endoscopic microsurgery-internal view demonstrating an excellent exposure of the lesion.

A: Sessile lesion being marked with a dotted line at about 1 cm around the border of the lesion; B: View after full thickness excision with exposed mesorectal fat.

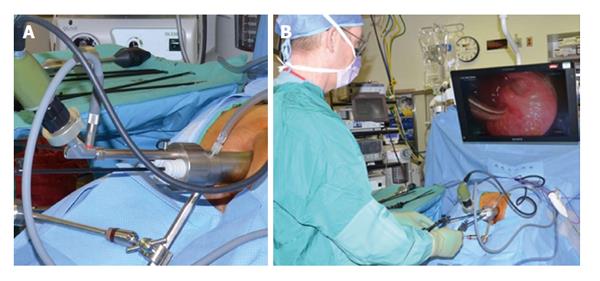

Figure 4 Transanal endoscopic microsurgery-external view.

A: Close-up to working anoscope with air insufflation, camera port, and 3 working ports; B: Surgeon and monitor position during procedure with a patient in prone-jackknife position.

- Citation: Devaraj B, Kaiser AM. Impact of technology on indications and limitations for transanal surgical removal of rectal neoplasms. World J Surg Proced 2015; 5(1): 1-13

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2832/full/v5/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5412/wjsp.v5.i1.1