INTRODUCTION

Naïve CD4 T cells can differentiate into effector or regulatory subsets, which will shape the quality and magnitude of adaptive immune responses[1]. Each CD4 T cell subset exhibits specialized functions in vivo that are determined by the transcription factors they express and the cytokines they secrete. The induction of the distinctive patterns of gene expression in CD4 T cell subsets is dictated by their interaction with the antigen-presenting cells (APC) and also the cytokines present in their environment during T cell activation. The variety of effector responses elicited by CD4 T cell subsets, endows the host with abilities to respond to different types of pathogens.

The ability of naïve CD4 T cells to differentiate into specialized variants was initially reported 30 years ago by Mossmann and Coffman who demonstrated the existence of two types of murine T helper clones, designed as Th1 and Th2, differing in their profiles of lymphokine activities[2]. Th1 cells secrete IFNγ and IL-2, and are responsible for cell-mediated immunity, including delayed-type hypersensitivity, which relies on macrophage activation. They are also responsible for both phagocyte activation and the production of opsonizing and complement-fixing antibodies by B lymphocytes. Th1 cells therefore critically contribute to defense against intracellular pathogens[3]. Th2 cells secrete interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5 and IL-13 cytokines and skew the immune response toward humoral immunity. They induce IgE class switching by B lymphocytes and favor the activity of eosinophils. They are effective in the protection against helminthes[4]. The differentiation of CD4+ T cells into Th1 or Th2 subsets can be replicated in vitro by adding IL-12 or IL-4, respectively, to cultures of naive T lymphocytes activated by their specific clonogenic antigen presented by APC like dendritic cells[5]. Interestingly, IFNγ produced by Th1 cells inhibits Th2 differentiation while IL-4 produced by Th2 cells inhibits Th1 differentiation[5]. Under physiological conditions, differentiated Th1 or Th2 cells can be regarded as stable cells[1].

Since the initial description of the Th1/Th2 dichotomy other subsets of CD4 T cells that suppress immune responses have been characterized including Foxp3 regulatory T cells (Tregs), which express the Foxp3 transcription factor, and IL-10-secreting Tr1 cells that rely on the transcription factors c-Maf and AhR for their development[6,7]. These two T cell subsets are essential to prevent excessive autoimmune responses and maintain host homeostasis.

In 2005 a new subset of CD4 helper T cells characterized by an abundant production of the IL-17A (also called IL-17) cytokine was identified and named Th17 cells[8]. Differentiation of Th17 cells from cultures of naïve mouse T cells was initially shown to be driven by the combination of the cytokines transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and IL-6[9]. It was subsequently shown that these cells, which rely on the transcription factor RORγt for their development[10], contribute to host defense against fungi. However, due to their secretion, besides IL-17A, of other proinflammatory mediators, including IL-17F, TNFα, GM-CSF and IL-22, dysregulated Th17 cell responses can also promote tissue inflammation in vivo[11].

Another subset of T helper CD4 T cells, Th9 cells, which can be differentiated from naive CD4 T cells in the presence of TGFβ and IL-4, was characterized in 2008 by the groups of Kuchroo and Stockinger as CD4 T cells lacking Foxp3 but secreting high levels of the cytokine IL-9[12,13]. Th9 cells can be induced in vitro from naïve T cells in the presence of TGFβ and IL-4 or derived from Th2 cells “reprogrammed” into Th9 cells by TGFβ[13]. Subsequent studies identified in 2010 PU.1 as the transcription factor responsible for Th9 cell development[14]. A characteristic of the Th9 phenotype is its plasticity, as illustrated by their ability to convert to IFNγ-secreting cells in the context of autoimmune diseases and asthma (reviewed in[15]). Nevertheless, Th9 cells feature a stable phenotype in cancer (reviewed in[16]). Another characteristic is the skin-tropism of Th9 cells that can contribute to their scarcity in the gut or circulation of healthy subjects[17]. The in vivo functions of Th9 cells are still being deciphered but it is clear that these cells promote inflammation in the context of colitis, asthma and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the mouse model for human multiple sclerosis[15]. Furthermore, both mouse and human studies indicate that Th9 cells also contribute to host defense against parasites, possibly due to their IL-9 secretion[15]. Recently, Th9 cells were also shown to exhibit potent anticancer properties upon adoptive transfer in vivo[16,18-20].

The differentiation of T cells into polarized subsets not only depends on the engagement of TCR signaling and the costimulatory signals but also on the presence of cytokines in the environment of differentiating T cells as discussed above. While polarized CD4 T cell subsets are now routinely obtained in vitro from naïve T cells in the presence of a relevant cytokine combinations such as TGFβ associated with IL-6 or IL-4 for mouse Th17 and Th9 cells, respectively, as discussed above, these cocktails should not be considered as representative conditions of natural Th17 or Th9 cell differentiation in vivo; nor as excluding the role of other cytokines in CD4 T cell differentiation. In this regard, many proinflammatory cytokines present in vivo in inflammatory or cancer settings will affect T cell development and shape T cell functions. In the present review, we will summarize information on the effect of cytokines belonging to the IL-1 family on CD4 T helper cell differentiation with a focus on the contribution of these cytokines to the differentiation of recently discovered Th17 and Th9 subsets. The physiological and clinical consequences of IL-1-driven alteration of CD4 T cell biology will also be discussed.

INTERLEUKIN-1 CYTOKINE FAMILY

IL-1β is, with IL-1α the original member of the IL-1 family that currently comprises 11 members including IL-18 and IL-33[21-23]. IL-1α and IL-1β act on a same receptor; the IL-1 type 1 receptor (IL-1RI). Another member of the IL-1 family, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), competitively binds to IL-1RI but without activating it and consequently is a natural inhibitor of IL-1α and IL-β. IL-1β is primarily secreted by activated macrophages and dendritic cells but is also released by B cells and NK cells upon stimulation. IL-1β is synthesized by these cells as an inactive precursor that has to be cleaved to an active mature cytokine by caspase-1 contained in multimeric complexes, the inflammasomes, activated during processes such as infections, autoimmunity or tumors[24]. Released IL-1β constitutes a soluble circulating cytokine that signals through the TIR domain of its receptor, IL-1RI, leading to the recruitment of the adaptor protein myeloid differentiation protein 88 (MyD88), the activation of NF-κB signaling and the induction of several proinflammatory genes. In contrast to IL-1β, IL-1α is not secreted but remains attached to the membrane of the producing cells that include not only myeloid cells but also epithelial and endothelial cells[23]. Consequently its effect is localized, contrasting with the diffuse, hormone-like effect of IL-1β. Like IL-1β, two other components of the IL-1 family, IL-18 and IL-33 were reported to act directly on T lymphocyte differentiation. IL-18 and IL-33 are widely expressed among epithelial cells constituting barriers in the gut, the lung and the skin. IL-18 is also expressed in myeloid cells, notably in antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages, whereas IL-33 is expressed in endothelial cells. Like IL-1β, IL-18 requires proteolysis by caspase-1 to be activated and released from an inactive precursor, while IL-33 does not requires this proteolytic step as its proform is fully active, and is preferentially released from damaged necrotic or dead cells as a danger signal[25]. Activated IL-18 acts through its specific receptor, IL-18R, while IL-33 acts through its specific receptor ST2 (known also as IL-33R or T1ST2), both IL-18R and ST2 belonging to the IL-1RI receptor family. While the involvement of IL-1 in inducing inflammation has been documented for more than 30 years, the effects of IL-1 family cytokines on the differentiation of CD4 T cell subsets are still being the subject of intense investigation, as discussed below.

EFFECT OF IL-1 CYTOKINES ON NAÏVE AND ON TH1 AND TH2 EFFECTOR T LYMPHOCYTES

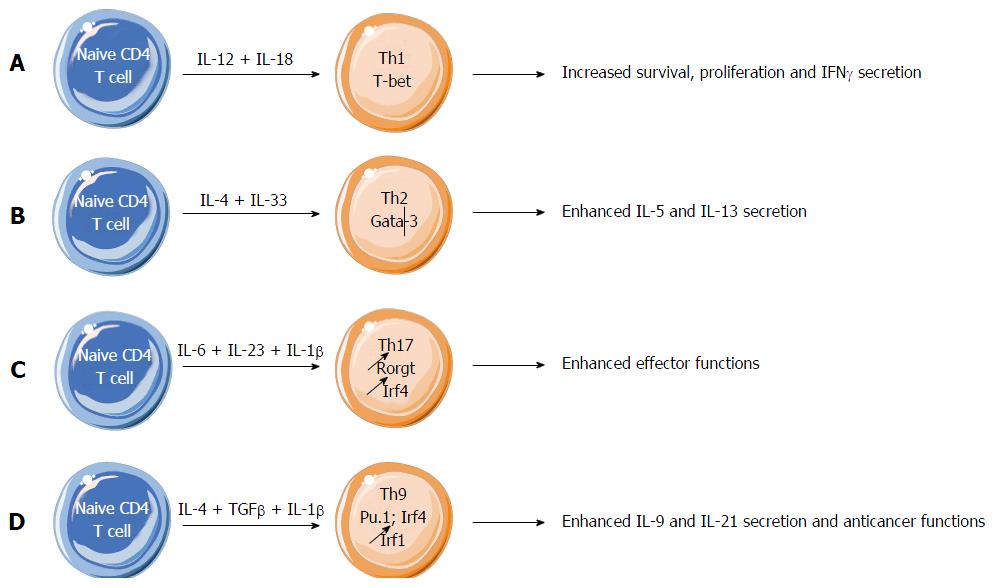

IL-1β induces proliferation and maturation of thymocytes and naïve T lymphocytes with the help of thymic accessory cells or their product, IL-7[26,27]. IL-1β acts as an adjuvant, enhancing antigen-driven expansion and differentiation of naïve and memory CD4 T cells[28]. An effect of IL-1β on mature Th1 and Th2 cells was the subject of controversy. It was initially established that Th2 cell lines expressed the IL-1RI receptor that is required for a direct effect of IL-1β on these cells, whereas this receptor was not detectable on Th1 cell lines, that restricted the IL-1β target to Th2 lymphocytes[29,30]. While an effect of IL-1 on T cells was initially investigated by determining its effect on the proliferation of mouse Th1 or Th2 clones, the quantification of signal cytokines was more recently preferred for determining the influence of IL-1 family cytokines on T cells. Using this criterion, it was found that the chief activators of signal cytokine production by Th1 or Th2 lymphocytes were not IL-1β but rather two other members of IL-1 family, IL-18 and IL-33[31-33]. The IL-18 receptor IL-18R was not detectable on naïve T cells, but was progressively expressed on differentiating Th1 cells, allowing IL-18 to promote cell proliferation and survival, and production of IFNγ (Figure 1A). The IL-33 receptor, ST2, is selectively expressed on Th2 cells. If Th2 cell lines are known to express IL-1RI, they express also predominantly ST2[31]. ST2 is not expressed on naïve, regulatory and Th1 lymphocytes[34]. ST2 allows IL-33 to enhance production of type-2 cytokines, in particular IL-5 and IL-13 by Th2 cells where it plays a major role in determining the Th2 phenotype compared with the IL-1RI receptor expressed on the same cells (Figure 1B). Consequently, IL-18 and IL-33 appeared as cytokines strictly specialized for Th1 and Th2 differentiation, respectively[33]. Further analyses showed however that IL-18 not only activates Th1 cells for producing IFNγ, but also Th2 cells through their ST2 receptor for releasing type-2 cytokines notably IL-5 and IL-13. Similarly, IL-33 can activate its ST2 receptor, but also the IL-18 receptor IL-18R for enhancing IFNγ release[33]. The common response to IL-18 and IL-33 was unexpected since IL-18R and ST2 receptors are respectively restricted to Th1 and Th2 cell lines. An explanation for this crossed reactivity could be the structural similarity between IL-18 and IL-33 that could permit a binding of each cytokine to both receptors. Consequently, IL-18 and IL-33 should be considered as Th1- and Th2-oriented, rather than Th1- and Th2-specific cytokines, respectively[33] (Figures 1A and B).

Figure 1 Effect of interleukin-1 family members on effector CD4 T cell differentiation.

A: Interleukin (IL)-18 promotes Th1 cell proliferation and survival, and production of IFNγ; B: IL-33 enhances Th2 cell differentiation and function, notably because of IL-33 driven increase of Th2-derived cytokines IL-5 and IL-13; C: IL-1β critically supports Th17 cell differentiation by maintaining the expression of IRF4 and RORγt, two key transcription factors necessary for Th17 cell development and functions; D: IL-1β enhances the expression of IRF1 in differentiating Th9 cells, leading to enhanced differentiation and effector functions of Th9 cells.

In spite of the predominance of IL-18 and IL-33 receptors, IL-1RI receptor is important for the induction of Th2 cell immunopathology. In experimental asthma induced in the mouse, airway hypersensibility responses to inhalation of ovalbumin were decreased in IL-1α- and IL-1β-deficient mice, while they were exacerbated in mice deficient in IL-1Ra[35,36]. The Th2 cell response mediated resistance to a gastrointestinal nematode was also dependent on the presence of IL-1α- and IL-1β lymphocytes, demonstrating the role of IL-1 in parasite elimination, an important function of Th2 cells[37].

EFFECT OF IL-1β CYTOKINE ON TH17 LYMPHOCYTES

While mouse Th17 cell differentiation was initially believed to solely rely on TGFβ and IL-6, it was clearly demonstrated that proinflammatory cytokines like IL-1β and TNFα could shape Th17 cell differentiation as well[38]. IL-1β was subsequently identified as a major actor in the physiology of Th17 cells, as illustrated for instance by its requirement for the development of Th17 cell-sustained autoimmunity like in EAE[39,40] (Figure 1C). IL-1 regulates the expression of IRF4 and RORγt, two transcription factors required for Th17 differentiation[40] (Figure 1C). Compared with Th1 and Th2 cells, mouse Th17 lymphocytes strongly express IL-1RI, the mandatory receptor for IL-1α and IL-1β[40]. This high expression of IL-1RI on murine Th17 cells is similar to the heightened expressions of IL-18R on Th1 cells and the heightened expression of ST2 on Th2 cells. Neither IL-18 nor IL-33 alone or in combination with STAT3 activators had any effect on IL-17 production[31].

IL-1RI is expressed on approximately 20% of CD4+ T cells in healthy human peripheral blood. The frequency of IL-1RI+ cells was higher (26%) in the memory CD4+ T-cell subset but IL-1RI+ cells were also present (15%) in the naive subset even though they were absent from human umbilical cord blood. This suggests that IL-1RI expression in naïve CD4+ T cells is induced at the periphery, likely through exposure to cytokines such as IL-7 or IL-15 and to TCR triggering[41]. Compared with IL-1RI-negative memory CD4+ T cells, IL-1RI+ memory CD4+ T cells produced higher levels of IL-17 in response to TCR triggering and this response was further increased in the presence of IL-1β. TCR activation and cytokines such as IL-7, IL-15 and TGFβ induced IL-1RI expression, allowing IL-1β to promote IL-17 production from initially IL-1RI-negative CD4+ T cells[41]. It is also noteworthy that human Th17 cells were proposed to originate from regulatory T cells (Tregs) differentiated in the presence of IL-2 and IL-1β[42]. In line with this, IL-1R1 expression on human CD4+ T cells represents an intermediate in the differentiation of Th17 from Tregs[43].

IL-23 is a critical cytokine in determining Th17 cell functions, as illustrated by early reports suggesting the lack of pathogenicity of TGFβ and IL-6- derived Th17 cells in the context of EAE[44]. Importantly, it was reported that mouse Th17 cell differentiation can proceed in the absence of TGFβ but in the presence of IL-6, IL-23 and IL-1β[45]. These cells were found to coexpress RORγt and T-bet, secrete IL-17 and IFNγ and are pathogenic in vivo in contrast to Th17 cells differentiated with TGFβ. In line with this, we noted that TGFβ and IL-6 favor the expression of two ectonucleotidases, CD39 and CD73 through down-regulation of the transcriptional repressor Gfi-1. The conjugated effect of these two nucleotidases is the production of immunosuppressive adenosine from ATP degradation. Differentiation of Th17 cells in the absence of TGFβ results in their lack of expression of ectonucleotidases. Accordingly, substitution of IL-1β to TGFβ for IL-17 cell generation leads to T cells with maintained anti-tumor cytolytic activity and higher capacity to delay tumor growth upon adoptive transfer[46,47].

EFFECT OF IL-1 CYTOKINES ON TH9 LYMPHOCYTES

Relatively to Th1, Th2 and even Th17 CD4 T cells, the Th9 subset was only recently characterized, first in mouse in 2008 then in humans in 2010. Its scarcity in healthy conditions explains the difficulty for collecting large number of Th9 cells, except through culture experiments in the presence of IL-4 and TGFβ for inducing Th9 polarisation of human or mouse naive CD4+ T cells. A study of the effects of IL-1 family cytokines on IL-9 expression by mouse CD4 T lymphocytes demonstrated that IL-1β, but also IL-1β, IL18 and possibly IL-33, could enhance IL-9 expression, even in the absence of IL-4, but only in the presence of TGFβ[48]. Stimulation of CD4 T cells by IL-1β and TGFβ induced a larger IL-9 expression than did the mixture of IL-4 and TGFβ conventionally used for inducing Th9 polarisation, and this response persisted even when induced by T cells from IL-4 KO mice[48]. Using human CD4 T cells, Wong et al[49] also reported that IL-1β enhances Th9 cell differentiation performed in vitro from naïve CD4 T cells polarized in the presence of TGFβ and IL-4. In our laboratory we have further explored the direct effects of IL-1 family cytokines on IL-9 expression from differentiating mouse Th9 cells derived from naïve CD4 T cells[18]. While we found no significant effect of IL-1α, IL-18 or IL-33 addition on IL-9 secretion from CD4 T cells derived under Th9-skewing conditions, IL-1β not only increased IL-9 expression but also drove the secretion of another cytokine, IL-21 from Th9 cells[18]. We found that IL-1β engaged the IL-1R1 receptor on differentiating Th9 cells, leading to the activation of MyD88-dependent intracellular signalling that induced the activation of the tyrosine kinase Fyn. This series of events led within 15 min after the beginning of the differentiation to the phosphorylation of the transcription factor STAT1, which ultimately bound to the IRF1 promoter and favoured IRF1 expression[18]. Subsequently, IRF1 bound to the promoters of the Il9 and Il21 genes and enhanced secretion of the corresponding cytokines by Th9 cells[18].

IL-21 is a pleiotropic cytokine produced primarily by natural killer T cells, T follicular helper cells and Th17 cells[50]. An IL-9-dependent antitumor effect of conventionally differentiated Th9 cells adoptively transferred was previously observed in mouse bearing B16-F10 melanoma or Lewis lung carcinoma[19,20]. The antitumor activity of Th9 lymphocytes was inhibited by a neutralizing anti-IL-9 antibody. The cellular mechanisms of this antitumor effect remained elusive as the role of mast cells and CD8 cytotoxic T cells was disputed[19,20] (and reviewed in[16]). We observed that Th9 cell antitumor activity was considerably increased when the adoptively transferred Th9 cells had been differentiated in the presence of IL-1β (Figure 1D). In contrast to conventionally differentiated Th9 cells, the antitumor activity of adoptively transferred Th9 cells differentiated in the presence of IL-1β was not dependent on IL-9 but was abrogated by a neutralizing anti-IL-21 antibody[18]. IL-21 acted by enhancing the activity of tumor-infiltrating and tumor-associated NK and CD8 cytolytic cells. Importantly, in this context of tumor, Th9 cells differentiated in the presence of IL-1β were stable, maintaining for several days expression of IL-9 and IL-21 in tumor tissues without acquiring the markers of transdifferentiation into Th1, Th2, Th17 or Treg markers[18]. Consequently, and also through their tropism to tumor tissues, Th9 cells differentiated in the presence of IL-1β could presumably constitute an interesting tool for cancer immunotherapy[16,18].

CONCLUSION

Since the discovery of the lack of IL-1RI on mouse Th1 cells, many studies focused on in vivo animal models of Th2 related diseases. Different models of mice either deficient for IL-1α/IL-1β or for their receptor IL-1RI were analyzed to determine the effects IL-1 family members on the Th2 response; and most, but not all, of these studies agree with the idea that both IL-1α and IL-1β promote proliferation and differentiation of Th2 cells in vitro and in vivo. Surprisingly few studies have investigated the effects of IL-1 on human Th2 cells, and the findings do not enlighten if human Th1 or Th2 cells express a functional IL-1RI and therefore can be modulated by IL-1α or IL-1β cytokines. Furthermore, recent studies demonstrated that the major IL-1 family cytokines directly acting on Th1 and Th2 cells are IL-18 and IL-33 rather than the classical IL-1α and IL-1β.

In contrast to the discrepant results obtained with Th1 and Th2 cells, animal models and human studies all agree with the concept that IL-1β has a fundamental role in Th17 modulation. The in vitro assays clearly demonstrate that IL-1β is able to induce the transcription factors necessary for Th17 development, as soon as its own receptor IL-1RI is upregulated in naïve T cells upon TCR triggering in the presence of γ-chain cytokines. IL-1RI expression is maintained on effector Th17 cells and this signaling is probably responsible for the prolonged survival of these cells during inflammation. This IL-1-driven enhanced Th17 cell activity has in vivo relevance. Nakae et al[51] have shown in a mouse model of arthritis that IL-1 drives the secretion of IL-17 from CD4 T cells, resulting in enhanced arthritis development[51]. These findings have possible clinical relevance given the ability of IL-1 neutralization using Anakinra, a recombinant version of IL-1Ra, to alleviate the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis[52]. However, whether the beneficial effect of IL-1Ra administration in inflammatory diseases results from the inhibition of Th17 responses remains elusive. In a cancer setting, we have shown that the treatment of tumor-bearing mice with the chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil leads to the in vivo release of IL-1β, the release of IL-17 from CD4 T cells and tumor progression[53]. Importantly, neutralization of IL-1β with IL-1Ra in vivo led to synergistic anticancer effects upon combination with 5-FU in mouse models. A clinical trial evaluating the possible benefit of IL-1Ra addition to 5-FU treatment in metastatic cancer patients is ongoing (NCT02090101). Thus, IL-1Ra-driven down-modulation of Th17 cell responses may be clinically relevant for the treatment of cancer and inflammatory diseases.

Finally, we found that IL-1β was able to enhance the differentiation of mouse naive CD4+ T cells into Th9 cells by considerably enhancing expression of IL-9 and IL-21 cytokines and efficiency of antitumor activity in several models of mouse tumors through CD8+ and NK cells. While we found in a mouse model of melanoma that the systemic administration of IL-1β enhanced the anticancer efficacy of adoptively transferred Th9 cells[18], these findings may be difficult to translate in the clinic because of the high toxicity profile of IL-1 administration in humans. We believe instead that our findings may be relevant in the context of adoptive T cell therapy with Th9 cells treated with IL-1β in vitro and given in combination with chemotherapy and/or immunomodulators. Thus, it will be important to determine if comparable IL-1β-modified Th9 cells can be obtained from human T lymphocytes, and if their antitumor activity could be even more increased by association with immune checkpoint inhibitors like PD-1, and whether appearance of autoimmune side effects could be a limitation for their use in cancer therapy.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Immunology

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Bamias GT, Chmiela M, Kwon HJ, Liu ML, Seong SY S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D