Published online Nov 27, 2014. doi: 10.5411/wji.v4.i3.194

Revised: October 12, 2014

Accepted: October 28, 2014

Published online: November 27, 2014

Processing time: 136 Days and 8.7 Hours

Liver disease has recently been described as an important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Liver test changes are useful surrogates of the burden of liver disease. Previous studies have shown that transaminase elevations are frequent among these patients. The cause of those changes is harder to establish in HIV-patients. We present a 61-year-old caucasian male, diagnosed with HIV type 1 infection since 1998, under highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART), with virological suppression and immunological recovery. He presented in a follow-up laboratory workup high values of transaminases, arthralgia at the hip joints and hepatomegaly. Liver function tests were normal. The antibodies to hepatitis viruses were negative. However, autoimmune study and liver biopsy were compatible with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). The AIH is a rare diagnosis in HIV-infected patients perhaps because the elevation of transaminases and changes in liver function tests are often associated to HAART or to other possible liver diseases, namely viral hepatitis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. The diagnosis may be underestimated. There are no specific recommendations available for the treatment of HIV-associated AIH although the immunosupression with slower tapering seems the most reasonable approach.

Core tip: Autoimmune hepatitis diagnosis is a rare diagnosis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients perhaps because the elevation of transaminases and changes in liver function tests are often attributed to the Highly Active Antiretroviral Treatment or to other possible liver diseases, namely viral hepatitis and Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. The diagnosis may be underestimated. There is no established treatment in those patients but it seems reasonable to consider immunosuppression also in HIV-infected patients.

- Citation: Moura MC, Pereira E, Braz V, Eloy C, Lopes J, Carneiro F, Araújo JP. Autoimmune hepatitis in a patient infected by HIV-1 and under highly active antiretroviral treatment: Case report and literature review. World J Immunol 2014; 4(3): 194-198

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2824/full/v4/i3/194.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5411/wji.v4.i3.194

Liver disease has recently been described as an important morbidity and mortality cause in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients and liver tests are typically part of routine care[1,2]. Liver dysfunction in HIV patients, at the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) era, mainly corresponded to opportunistic infections, like cytomegalovirus (CMV), mycobacteria and leishmaniasis; cholangitis related to AIDS caused by parasitic infections like cryptosporidiosis and microsporidiosis; tumors like lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma; hepatitis related with medication caused by antibiotics like trimetoprim-sulfamethoxazol[3]. Alcohol or drugs may also be considered[1]. With the rising obesity epidemic, reports have suggested that non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) may be an important cause of liver disease in the general population, but data among HIV-infected patients are more limited[1].

In AIH there is a loss of immune tolerance to antigens on hepatocytes with hepatic parenchyma is destruction by auto-reactive T cells[4]. T cells CD4+ and CD8+ interaction towards effector responses mediated by NK cells and cdT cells plays a major role in immunopathogenesis[4]. Many factors have been identified as possible triggers: viruses, xenobiotics, and drugs. This may suggest that regulatory T-cells (Treg) defects might be related to the pathogenesis of AIH[4].

AIH diagnosis relies in several aspects: clinic, biochemistry, immunology and histology features (Table 1)[4].

| Parameters | Diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis |

| Clinical | Female gender |

| Association with other autoimmune diseases | |

| Autoantibodies | ANA or SMA > 1:40 (type 1) |

| LKM > 1:40 (type 2) | |

| SLA + (type 3) | |

| Immunoglobulin | IgG > upper normal limit |

| Biochemistry | Hepatitic pattern (raised AST and ALT levels) |

| Histology | Plasma cell-rich mononuclear infiltrate |

| Interface hepatitis with ballooning and rosetting of peri-portal hepatocyte; ± peri-portal fibrosis | |

| Lobular necroinflammatory activity | |

| No bile duct loss or chronic cholestasis | |

| Radiology and ERCP | Normal |

| Exclusion of other etiology | Exclusion of viral, metabolic, drug and alcoholic etiology |

| Response to steroid | Good |

The International Autoimmune Hepatitis Working Group (IAHG), created a score in order to develop uniform diagnostic criteria. If left untreated, the prognosis of AIH is poor, the rates for 5 and 10-year survival are, respectively, 50% and 10%[4,5]. The therapy with prednisolone leads to better survival[4]. Cirrhosis at diagnosis is present on histology in up to 30% of adult patients[4].

The two phases of standard therapy are: high-dose of corticosteroids for induction of remission and low-dose corticosteroids and azathioprine for maintenance[4]. On prednisolone and azathioprine, more than 80% of the patients will achieve remission[4].

There are fourteen case reports in the literature of AIH in HIV patients[6-9].

The patient was a 61-year-old caucasian male, married, carpenter, emigrant in France. He was diagnosed with HIV type 1 infection since 1998, sexually acquired, under HAART - Zidovudine 300 mg tid, Lamivudine 150 mg bid and Atazanavir 200 mg bid, with virological suppression and immunological recovery (CD4+ cell count of 779/mm3). He was a smoker, he had no history of alcohol consumption or drug abuse. No new medications were introduced in the previous six months, neither over-the-counter medication. He was followed in Portugal in Infectious Diseases’ consultations where he was observed twice a year.

In a follow-up laboratory workup, transaminases elevation was detected: ALT (437 U/L), AST (227 U/L) and GGT (220 U/L). These values decreased in three months and increased again after, reaching the highest values at six months: ALT (684 U/L, almost 20 times above the upper normal limit), AST (367 U/L,10 times above the upper normal limit) and GGT (290 U/L). The alkaline phosphatase was normal. Bilirubin levels were elevated, both total (4.67 mg/dL) and conjugated (0.69 mg/dL). The total protein, albumin and coagulation parameters were normal. His CD4 count was 779/mm3.

At that time, he presented with severe arthralgia at the hip joints with no other symptoms. Jaundice, rash, petechiae, lymphadenopathy, lipodystrophy or parotid hypertrophy were absent. Arterial blood pressure tended to be low (95/65 mmHg). Signs of hypervolemia namely jugular venous distension, hepatojugular reflux, pulmonary stasis, or edema were not identified. The abdominal examination revealed hepatomegaly; the spleen was not palpable.

Some laboratory tests were performed in an attempt to elucidate the etiology of transaminase elevations. The cell blood count and platelets count were normal. Lipid profile was normal (Table 2). He was immune to hepatitis B and antibodies to hepatitis viruses A (HAV), B (HBV) and C (HCV) were negative. The copper metabolism was normal (Table 2), excluding Wilson disease. There were alterations in iron metabolism (Table 2) with high values of transferrin saturation (84%). Hemochromatosis was excluded, he was heterozygous to the HFE gene (without mutation). The alpha 1 antitrypsin value was normal. The autoimmunity assays revealed anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) of 1/1000 with a nucleolar pattern and a slightly positive anti smooth-muscle antibody (SMA). The seric protein electrophoresis and IgG levels were normal. The alpha fetoprotein was normal. The abdominal ultrasound showed a normal sized liver with an heterogenous appearance but without focal lesions, normal biliary ducts, a portal vein with normal caliber and patent; the pancreas and spleen were normal.

| Auto-immunity | 11.2009 | Reference values |

| ANA | > 1/1000 nucleolar | < 1/100 |

| SMA | Slightly positive | Negative |

| Copper Metabolism | ||

| Copper (mcg/dL) | 92 | 50-140 |

| Ceruloplasmin (mg/dL) | 24.6 | 18-45 |

| Iron Metabolism | ||

| Iron (mcg/dL) | 274 | 53-167 |

| Transferrin (mg/dL) | 233 | 206-360 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 1274.8 | 16.4-293.9 |

| Transferrin Saturation (%) | 84 | 15-50 (males) |

| Lipid Profile | ||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 140 | < 200 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 83 | < 130 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 41 | > 40 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 69 | < 150 |

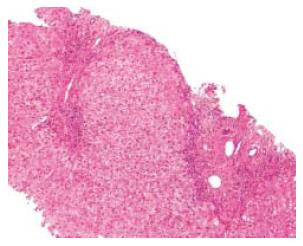

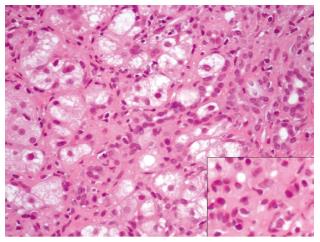

A transthoracic percussion guided liver biopsy was performed after five months, without complications. The histological study showed portal fibrosis with porto-portal bridging (Figure 1). Density of inflammatory infiltrates was variable in portal ducts. Piece-meal necrosis was identified in the periphery of portal ducts and septa (interface hepatitis). Inflammatory infiltrates were also seen in the sinusoids were plasma cells (isolated or in aggregates) were easily identified (Figure 2). No signs of viral inclusions were identified. Immunostaining for CMV was negative. In the clinical and analytical setting of the patient, the diagnosis of AIH was strongly favoured. The definite diagnosis was type I AIH with a pre-treatment score of 16.

He started corticosteroids with prednisolone 60 mg per day and kept the HAART scheme he was doing. The clinical response to the treatment was good leading to the reduction of corticosteroid dose to 40 mg per day after two months of therapy. Then, corticosteroid dose was reduced to 30 mg per day after five months and azathioprine 25 mg per day was added at seven months of therapy. After eighteen months, the transaminases levels were normal.

There was no infectious complication. Also, he showed sustained virological suppression and exhibited immunological recovery with CD4+ cell count of 1619/mm3 after starting the immunosuppressive treatment with azathioprine.

Liver test changes are being found increasingly on testing for other symptoms or diseases and HIV patients treated with HAART present them frequently[1,2]. Those changes are influenced by hepatotoxicity to medication, co-infections by hepatotropic virus, other liver diseases (steatosis and metabolic diseases), alcohol and drugs mediated hepatotoxicity[4]. More severe biochemical and pathological liver disease results from the interplay between liver lesions, leading to greater progression of fibrosis which may be triggered by greater sensitivity to toxic agents (alcohol and drug), HAART worsening underlying steatosis, HCV cytotoxicity especially in the cases of an increased HCV load in the liver. However, some studies show that the use of medications was not significantly associated with liver abnormalities in HIV-infected patients[4]. Also, 51% of abnormal liver tests are unexplained[1].

Clinical history was negative for risk factors such as alcohol, drugs and over-the-counter or prescribed medications, except for HAART. The latter was not discontinued or changed since it was established. In biochemical study alterations concerning iron metabolism might be reactive in nature since hemochromatosis was excluded. The increased levels of autoantibodies (ANAs and anti-SMA) raised the probability of AIH and a liver biopsy was performed in the absence of contra-indications. Due to indolent changes on liver tests and to the patient only visited Portugal twice a year, liver biopsy was postponed a couple of months. The objectives were to confirm the diagnosis of AIH; to evaluate disease severity at the baseline for immunosuppressive therapy for better evaluation of response; for stratification of liver disease; for prognostic information (immunosuppression may improve interface hepatitis whereas fibrosis or cirrhosis usually occur from established bridging necrosis), which is associated with an adverse prognosis and to evaluate putative co-existent lesions[4,5].

The diagnosis of AIH was confirmed according to the criteria of the IAHG and the patient scored 16. The score has high sensitivity and specificity but with concomitant diseases like non-alcoholic fatty liver, biliary disease or fulminant hepatitis, it does not perform so well[4,5]. Importantly, there are no studies on the use of this score in patients infected with HIV.

The diagnosis of AIH in HIV-infected patients is hard to support because usually HIV-infection is considered has being protective against autoimmunity. However, there are many mechanisms proposed by which HIV-infection may predispose to autoimmunity.

It is thought that viral infections may generate a proper environment, pro-inflammatory, that overcomes regulatory networks resulting in the generation and self-perpetuating of autoimmune reactions[4]. So, the virus itself may be a trigger.

AIH seems to be related with Treg defects in both the number and function. Regulatory T cells are a necessary component of the immune homeostasis[4]. It is not known if their function is similar in HIV-infected patients. Clarification of the Treg function, molecular and cellular bases may help to AIH management[4].

The Th17 T cells are crucial in autoimmunity[4]. In the HIV-infected patient we don’t know how this balance is achieved and perhaps there are some alterations in the proportion of CD4+ T-cell. It means that an unbalance towards the higher prevalence of Th17 T cells may be present and may be an explanation for triggering autoimmunity in HIV-infected patients. In our patient, this unbalance may be supported for the fact that he had immunological recovery in the period that the liver test abnormalities settled, with CD4+ T-cells always above 700/mm3, which means that some of these T-cells were maybe directed towards the production of Th17 T cells.

Another suggested mechanism is the role of immune restoration[1,4,7-9], something that can’t be an explanation in our patient because he already had immunological recovery. Also, is difficult to establish the link between immune restoration and liver deterioration[4].

Uncontrolled viral replication was suggested as possible mechanism[10]. Our patient always had virological suppression while he developed the liver test abnormalities.

Homeostasis in the liver is maintained by complex networks of effector and regulatory lymphocytes and its impairment may result in a proper local environment leads to disruption of autoimmunity and AIH[4]. The case herein presented is different from those previously reported because the AIH results from a conjunction of factors independent of the virological suppression and immunological recovery.

Another interesting possibility is the genetic susceptibility. HLA-DR3 (A1-B8-DR3) and DR4 make more probable the recognition of self-antigens despite adequate thymic selection: increase susceptibility to type 1 AIH and DR7 associated with type 2 AIH and immune responses against hepatocyte enzyme CYP2D6[4]. This hypothesis was not evaluated in our patient and it remains to be elucidated the role of this mechanism in HIV-infected patients.

According to the recommendations of the IAHG for AIH management, our patient fulfilled the criteria for treatment: AST > 10 fold, multiacinar necrosis in the liver biopsy and disabling symptoms.

No specific recommendations are available for the treatment of HIV-associated AIH. In the present case we decided for immunosuppression with corticosteroids at the dose generally used in other AIHs. However, corticosteroids dose reduction was slower than usual and azathioprine was introduced only seven months after the beginning of treatment and in a lower dose. The limited experience and small amount of studies considering the treatment of AIH in an HIV-infected patient and the fact that we only could evaluate this patient twice a year made us follow an individualized scheme of treatment in the case herein reported.

AIH is a rare diagnosis in HIV-infected patients perhaps because the elevation of transaminases and changes in liver function tests are often attributed to the HAART or to other possible liver diseases, namely viral hepatitis and NASH. So, the diagnosis may be underestimated. Also, the liver biopsy should be performed while evaluating hepatitis of undetermined etiology in HIV-infected patients. Many possible mechanisms were suggested to explain the pathogenesis of AIH in HIV-infected patients. The treatment has to be individualized after consideration of the risks and benefits but it seems reasonable to consider that immunosuppression should not be postponed in HIV patients.

We acknowledge to the Serviço de Anatomia Patológica, Centro Hospitalar de São João, especially to Professor Drª Fátima Carneiro for her support, contribution to discussion and empowerment of my scientific and academic work. All authors report no conflict of interests.

A 61-year-old male Caucasian patient with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infection under highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) presented with arthralgia, hepatomegaly and changes in liver tests.

Autoimmune hepatitis in an HIV-1 patient under HAART.

Hepatotoxicity to medication, co-infections by hepatotropic virus and parasites, other liver diseases like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic diseases, alcohol and drugs mediated hepatotoxicity.

Elevated transaminase values, positive anti-nuclear antibody of 1/1000 with a nucleolar pattern and a slightly positive anti smooth-muscle antibody.

Trans-thoracic liver biopsy.

Liver biopsy histology showed piece-meal necrosis identified in the periphery of portal ducts and septa (interface hepatitis) and inflammatory infiltrates were also seen in the sinusoids were plasma cells (isolated or in aggregates).

Standard treatment adapted with corticosteroids and azathioprine in lower doses and slower tapering.

Liver test changes etiology is hard to establish in patients with HIV-1 infection and sometimes lead to changes in HAART therapy doses because they are easily attributed to secondary effects of the medication.

Liver test changes in HIV-1 patients should be looked up carefully: autoimmune hepatitis is a possible etiology (although the mechanism is not totally understood) and it should be treated in with an adapted standard treatment probably with lower doses and slower tapering.

Nice case report.

P- Reviewer: A-Kader HH, McQuillan GM, Teschke R S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Crum-Cianflone N, Collins G, Medina S, Asher D, Campin R, Bavaro M, Hale B, Hames C. Prevalence and factors associated with liver test abnormalities among human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:183-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ioannou GN, Boyko EJ, Lee SP. The prevalence and predictors of elevated serum aminotransferase activity in the United States in 1999-2002. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:76-82. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Pol S, Lebray P, Vallet-Pichard A. HIV infection and hepatic enzyme abnormalities: intricacies of the pathogenic mechanisms. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38 Suppl 2:S65-S72. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Oo YH, Hubscher SG, Adams DH. Autoimmune hepatitis: new paradigms in the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:475-493. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, Krawitt EL, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Vierling JM. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193-2213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1039] [Cited by in RCA: 1010] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Puius YA, Dove LM, Brust DG, Shah DP, Lefkowitch JH. Three cases of autoimmune hepatitis in HIV-infected patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:425-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | German V, Vassiloyanakopoulos A, Sampaziotis D, Giannakos G. Autoimmune hepatitis in an HIV infected patient that responded to antiretroviral therapy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:148-151. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Daas H, Khatib R, Nasser H, Kamran F, Higgins M, Saravolatz L. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and autoimmune hepatitis during highly active anti-retroviral treatment: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | O'Leary JG, Zachary K, Misdraji J, Chung RT. De novo autoimmune hepatitis during immune reconstitution in an HIV-infected patient receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:e12-e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Esposito A, Conti V, Cagliuso M, Pastori D, Fantauzzi A, Mezzaroma I. Management of HIV-1 associated hepatitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: role of a successful control of viral replication. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8:9. [PubMed] |