Peer-review started: April 9, 2020

First decision: June 7, 2020

Revised: July 16, 2020

Accepted: August 15, 2020

Article in press: August 15, 2020

Published online: September 12, 2020

Processing time: 152 Days and 14.3 Hours

Ureteral stent and nephroureterostomy tube (NUT) are treatments of ureteral obstruction. Ureteral stent provides better quality of life. Internalization of NUT is desired whenever possible.

To assess outcomes of capping trial among cancer patients with complete aspiration of retained contrast from bladder via NUT.

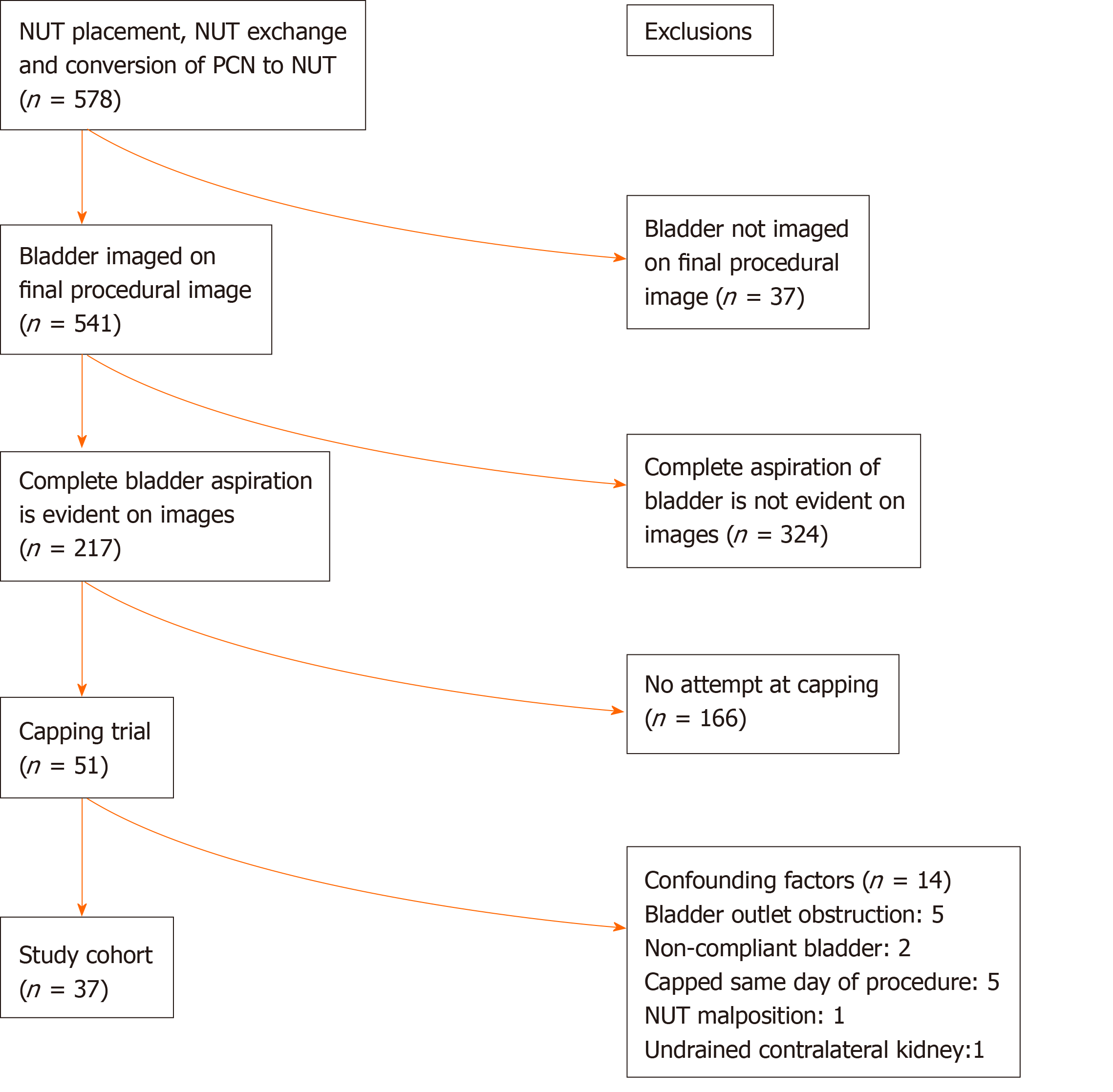

Our Institutional Review Board approved retrospective review of all NUT placement, NUT exchange and conversion of nephrostomy catheter into NUT performed during June 2013 to June 2015 (n = 578). Cases were excluded due to lack of imaging of bladder (n = 37), incomplete aspiration of bladder (n = 324), no attempt at capping NUT (n = 166), and patients with confounding factors interfering with results of capping trial including non-compliant bladder, bladder outlet obstruction and catheter malposition (n = 14). Study group consisted of 37 procedures in 34 patients (male 19, female 15, age 2-83 years, average 58, median 61) most with cancer (prostate 8, endometrial 5, bladder 4, colorectal 4, breast 2, gastric 2, neuroblastoma 2, cervical 1, ovarian 1, renal 1, sarcoma 1, urothelial 1 and testicular 1) and one with Crohn’s disease. Medical records were reviewed to assess outcomes of capping trial. Exact 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated.

Among patients with complete aspiration of retained contrast, 30 (81%, 95%CI: 0.65-0.92) catheters were successfully capped (range 12-94 d, average 40, median 24.5) until planned conversion to internal stent (23), routine exchange (5), removal (1) or death unrelated to catheter (1). Seven capping trials (19%, 95%CI: 0.08-0.35) were unsuccessful (range 2-22 d, average 12, median 10) due to leakage (3), elevated creatinine (2), fever/hematuria (1) and nausea/vomiting (1).

Capping trial success among patients with complete aspiration of retained contrast/urine from bladder via NUT appears high.

Core Tip: Patients with ureteral obstruction are best treated with cystoscopic placement of ureteral stent because of a better quality of life. When ureteral stent placement is not possible, a nephroureterostomy tube (NUT) is placed. Once the acute clinical problem is resolved, internalization is sought in order to improve patient’s quality of life. Currently all patients undergo NUT capping trial which is needed before internalization. This work helps urologists and interventional radiologists to estimate success of capping trial. It helps define the endpoint of NUT placement or exchange interventions with potential benefits to patients and health care systems.

- Citation: Maybody M, Shay WK, Fleischer DA, Hsu M, Moskowitz C. Estimation of successful capping with complete aspiration of bladder via nephroureterostomy tube. World J Clin Urol 2020; 9(1): 1-8

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2816/full/v9/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5410/wjcu.v9.i1.1

Patients with ureteral obstruction are commonly treated with cystoscopic placement of ureteral stent. Compared to percutaneous approach with externalized catheter, cystoscopic approach is less invasive and the ureteral stent provides a better quality of life to patients. When ureteral stent placement is not possible or when it fails to alleviate hydronephrosis, percutaneous approach is indicated. This is achieved by placing percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) catheter or nephroureterostomy tube (NUT). Once the acute clinical problem is resolved, internalization is sought in order to improve patient’s quality of life. In case of PCN it is converted to NUT first. The NUT is capped for a few days (capping trial) simulating the presence of ureteral stent without the exteriorized catheter. If capping trial is successful, then NUT is converted to ureteral stent (internalization). A successful capping trial is defined when all of the below criteria are met: Lack of fever, lack of rise in serum creatinine level, lack of peri catheter leakage, lack of ipsilateral flank pain and lack of pelvic symptoms such as urgency, incontinence and pain.

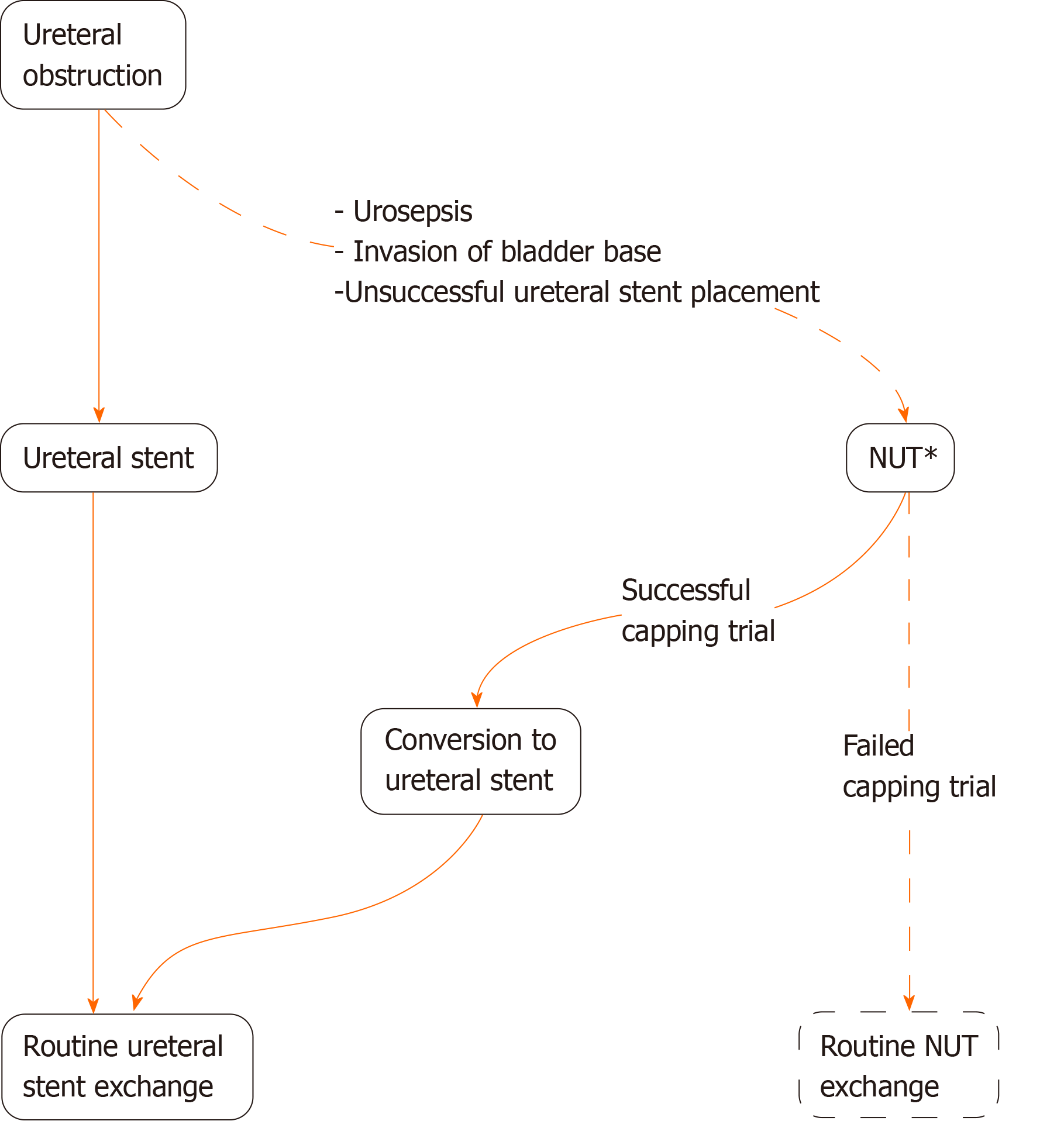

After a failed capping trial, patients usually undergo catheter exchange with upsizing and/or change of catheter length in order to improve the outcome of the next trial. In some patients this process is repeated a few times. Currently all patients undergo capping trial(s) as a diagnostic intervention because there is no way of estimating the result. Estimating success of capping trial is helpful. It can help define the endpoint of a catheter exchange intervention with potential benefits to patients and health care systems. Some cancer patients with successful capping trial prefer to carry a capped NUT that can be uncapped if needed over an internal stent. The management algorithm for ureteral obstruction is shown in Figure 1.

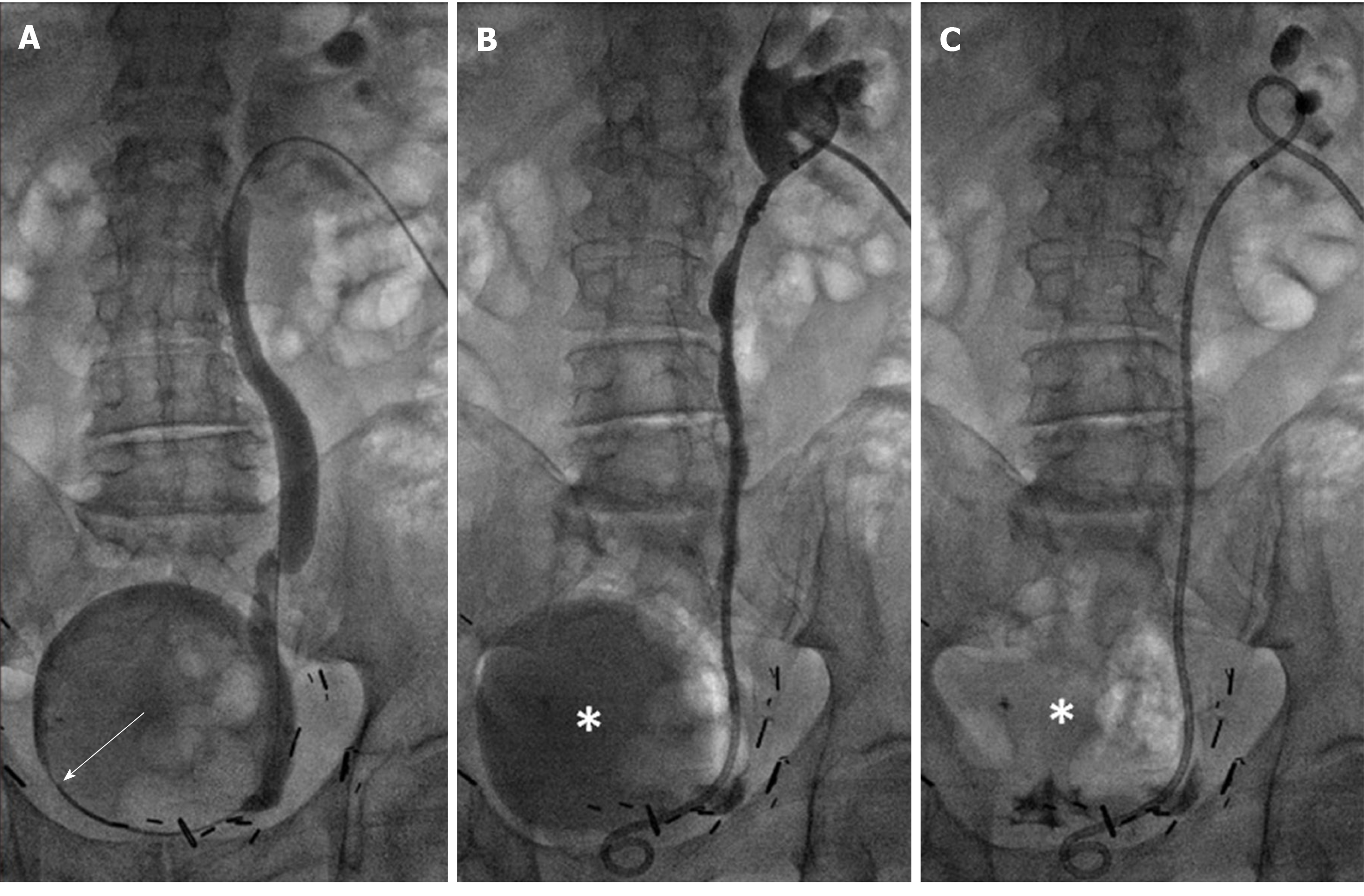

Our Institutional Review Board approved retrospective review of all patients who underwent NUT placement, NUT exchange and conversion of PCN into NUT performed from June 2013 to June 2015. This included 578 procedures. Patients in whom complete aspiration of retained contrast/urine in bladder was evident followed by a capping trial were selected. The inclusion criteria were presence of NUT at the end of procedure, visualization of bladder on final procedural image, presence of discernible amount of contrast/urine in bladder during procedure, resolution of contrast from bladder on final procedural images, initiation of capping trial at least one d after the procedure and lack of confounding factors that interfere with capping trial (Figure 2).

The confounding factors were bladder outlet obstruction, noncompliant bladder, presence of Foley catheter in bladder (may mask pelvic symptoms), undrained obstructed contralateral kidney (interferes with interpretation of serum creatinine level), capping on the same d of procedure (not standard practice, higher risk for failure due to acute inflammation or bleeding from a fresh procedure) and malpositioning of NUT during capping trial that required catheter exchange (mimics capping failure by peri catheter leakage).

Cases were excluded due to lack of imaging of bladder on final procedural images (n = 37), uncertainty about complete aspiration of bladder (n = 324), no attempt at capping NUT (n = 166), confounding factors interfering with interpretation of capping trial (n = 14) (Figure 3).

Because some patients may become uroseptic with forceful injection of contrast antegradely into the renal pelvis, it is our standard practice to avoid forceful injection into NUT and to not pursue contrast flow into the bladder. The study was designed to only capture patients in whom procedural images were conclusive of aspiration of contrast from the bladder through NUT. Study cohort consisted of 37 procedures in 34 patients (male 19, female 15, age 2-83 years, average 58, median 61) (Table 1) mostly with cancer (prostate 8, endometrial 5, bladder 4, colorectal 4, breast 2, gastric 2, neuroblastoma 2, cervical 1, ovarian 1, renal 1, sarcoma 1, urothelial 1 and testicular 1) and one with Crohn’s disease. Medical records including imaging studies, lab results, outpatient clinic visits, inpatient progress notes and interventional radiology records were reviewed to assess outcomes of capping trial. Successful capping trial was defined by lack of symptoms of failure until the goal of capping was achieved. The goals are conversion of NUT to ureteral stent, removal of NUT and routine exchange of capped NUT.

| Total | Successful capping | Unsuccessful capping | |

| NUT procedures | 37 | 30 (81%), 95%CI: 0.65-0.92 | 7 (19%), 95%CI: 0.80-0.35 |

| Patients | 34 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 19 | 17 | 2 |

| Female | 15 | 10 | 5 |

| Age (yr) | |||

| Average (range) | 58 (2-83) | 59 (2-83) | 56 (24-73) |

| Underlying cancer (procedures) | |||

| Prostate: 9 | Prostate: 7 | Prostate: 2 | |

| Bladder: 5 | Bladder: 5 | ||

| Colorectal: 5 | Colorectal: 5 | ||

| Endometrial: 5 | Endometrial: 3 | Endometrial: 2 | |

| Breast: 2 | Breast: 1 | Breast: 1 | |

| Cervical: 2 | Cervical: 2 | ||

| Gastric: 2 | Gastric: 1 | Gastric: 1 | |

| Neuroblastoma: 2 | Neuroblastoma: 2 | ||

| Ovarian: 1 | Ovarian: 1 | ||

| Renal: 1 | Renal: 1 | ||

| Sarcoma: 1 | Sarcoma: 1 | ||

| Testicular: 1 | Testicular: 1 | ||

| Crohn’s: 1 | Crohn’s: 1 | ||

| Catheter size (French) | |||

| 8.5 | 14 | 11 | 3 |

| 10 | 23 | 19 | 4 |

| Catheter length (cm) | |||

| 22 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| 24 | 16 | 13 | 3 |

| 26 | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| 28 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 32 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Side | |||

| Right | 18 | 16 | 2 |

| Left | 10 | 6 | 4 |

| Bilateral | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Capping length (d) | |||

| Average, Median, Range | 40, 24.5, 12-94 | 12, 10, 2-22 | |

| Outcomes | Conversion to internal stent (n = 23); Routine exchange (n = 5); Removal (n = 1); Unrelated death (n = 1) | Peri catheter leakage (n = 3); Elevated creatinine (n = 2); Fever/hematuria (n = 1); Nausea/vomiting (n = 1) |

The proportion of procedures that were successfully capped was estimated among patients with complete aspiration of retained contrast. Exact 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated.

Among the study cohort, 30 (81%, 95%CI: 0.65-0.92) had successful capping with a median length of capping of 24.5 d (range 12-94 d) until planned goal of conversion to internal stent (n = 23), routine exchange (n = 5) or removal (n = 1) and one patient who expired for reasons unrelated to catheter (n = 1). Substantially fewer patients had unsuccessful capping result (n = 7, 19%, 95%CI: 0.08-0.35) had median length of capping of 10 d (range 2-22 d) due to leakage (n = 3), elevated creatinine (n = 2), fever/hematuria (n = 1) and nausea/vomiting (n = 1).

Mechanical obstruction to the flow of urine from kidney to bladder can be due to a variety of etiologies. Among these include primary tumors involving the ureters or bladder, tumors or other space occupying lesions within abdomen and pelvis that compress ureters externally, nephrolithiasis and iatrogenic causes such as surgery. Acute obstruction is symptomatic and may result in urosepsis in some patients. Chronic obstruction mainly interferes with renal function. The first line of management for ureteral obstruction is cystoscopic placement a ureteral stent. This approach provides patients with better quality of life due to lack of external catheter and drainage bag. Cystoscopy may not be possible when tumors involve the base of bladder. If hydronephrosis does not resolve, the stent is considered failed. Patients with hemodynamic instability and urosepsis are not favorable candidates for cystoscopic approach. These scenarios account for 36%-53% of malignant ureteral obstructions and percutaneous approach is advised[1,2]. Once the obstructing etiology is resolved the ureteral stent, PCN or NUT are removed. However, this is not always possible, and many patients remain dependent on these catheters. The external catheter puts limitations on patient’s quality of life. For example, they cannot bathe or swim. Maintaining the gravity drainage bag is cumbersome and the catheter may get dislodged by incidental traction. It has been shown that both ureteral stent and external catheters have comparable complication rates[2,3]. Since ureteral stent provides better quality of life, unless there is need for permanent urinary diversion which is achieved only by PCN, the optimal long-term plan is to convert external catheter into ureteral stent whenever possible. In case of PCN and in the absence of need for permanent urinary diversion, it needs to be converted to NUT first. NUT is capped for a few days to simulate lack of external component. If the capping trial is successful, the NUT is converted to ureteral stent. Predictors of ureteral stent outcomes including invasion of bladder base by tumor and degree of hydronephrosis have been published[4-7]. There is no data in the literature about predictors of success for internalization in patients who receive external catheters and the percentage of patients who can ultimately be internalized. Having an indicator of favorable capping trial outcome is helpful in clinical decision-making and defining the endpoint of a catheter exchange intervention. We observed that at the conclusion of an intervention where a NUT is present if the retained contrast/urine in bladder can be aspirated through the NUT there is a high proportion of a successful capping trial. If bladder contrast/urine cannot be aspirated through the newly placed/exchanged NUT, the interventionalist may exchange the catheter with larger caliber or another length at the same sitting. This may save time and resources obviating the results of the next capping trial.

This study has several limitations including its retrospective design, small size of study cohort and lack of control group. Our results are based on cancer patients with malignant ureteral obstruction and applicability of the results to non-cancer patients is not known. Since aspiration of retained contrast/urine from the bladder through the NUT is not standard practice and this description is not included in official dictations, we could only rely on cases where retained contrast/urine was completely aspirated on final procedural images. This created many exclusions which potentially skew the results.

Ureteral stent and nephroureterostomy tube (NUT) are treatments of ureteral obstruction. Ureteral stent provides better quality of life. Internalization of NUT is desired whenever possible.

Before internalization of NUT patients should pass a capping trial. Currently there are no indicators of capping trial results.

To help urologists and interventional radiologists estimate successful capping trial during a NUT placement or exchange intervention. By preventing unsuccessful trials, patients and healthcare systems benefit.

578 NUT placement, NUT exchange and conversion of nephrostomy catheter into NUT performed between 2013 and 2015 were reviewed. Exclusions were due to lack of imaging of bladder (n = 37), incomplete aspiration of bladder (n = 324), no attempt at capping NUT (n = 166), and patients with confounding factors interfering with results of capping trial (n = 14). Study group consisted of 37 procedures in 34 patients (male 19, female 15, age 2-83 years, average 58, median 61) most with cancer (prostate 8, endometrial 5, bladder 4, colorectal 4, breast 2, gastric 2, neuroblastoma 2, cervical 1, ovarian 1, renal 1, sarcoma 1, urothelial 1 and testicular 1) and one with Crohn’s disease. Medical records were reviewed to assess outcomes of capping trial. Exact 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

In 81% of study group (95% confidence intervals: 0.65-0.92) NUTs were successfully capped (range 12-94 d, average 40, median 24.5) until planned conversion to internal stent (23), routine exchange (5), removal (1) or death unrelated to catheter (1).

The ability to aspirate retained contrast from bladder through NUT is an indicator for successful capping trial. If contrast cannot be aspirated form bladder through NUT, same session tube exchange (upsize or different length) should be considered.

Prospective studies are required to further assess the findings of this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Society of Interventional Oncology (United States); and Society of Interventional Radiology (United States).

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cantiello F S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Ganatra AM, Loughlin KR. The management of malignant ureteral obstruction treated with ureteral stents. J Urol. 2005;174:2125-2128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ku JH, Lee SW, Jeon HG, Kim HH, Oh SJ. Percutaneous nephrostomy versus indwelling ureteral stents in the management of extrinsic ureteral obstruction in advanced malignancies: are there differences? Urology. 2004;64:895-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Alawneh A, Tuqan W, Innabi A, Al-Nimer Y, Azzouqah O, Rimawi D, Taqash A, Elkhatib M, Klepstad P. Clinical Factors Associated With a Short Survival Time After Percutaneous Nephrostomy for Ureteric Obstruction in Cancer Patients: An Updated Model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:255-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yossepowitch O, Lifshitz DA, Dekel Y, Gross M, Keidar DM, Neuman M, Livne PM, Baniel J. Predicting the success of retrograde stenting for managing ureteral obstruction. J Urol. 2001;166:1746-1749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Matsuura H, Arase S, Hori Y. Ureteral stents for malignant extrinsic ureteral obstruction: outcomes and factors predicting stent failure. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:306-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang JY, Zhang HL, Zhu Y, Qin XJ, Dai BO, Ye DW. Predicting the failure of retrograde ureteral stent insertion for managing malignant ureteral obstruction in outpatients. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:879-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fiuk J, Bao Y, Calleary JG, Schwartz BF, Denstedt JD. The use of internal stents in chronic ureteral obstruction. J Urol. 2015;193:1092-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |