Published online Mar 24, 2016. doi: 10.5410/wjcu.v5.i1.1

Peer-review started: September 22, 2015

First decision: November 24, 2015

Revised: December 15, 2015

Accepted: February 23, 2016

Article in press: February 24, 2016

Published online: March 24, 2016

Processing time: 179 Days and 13.9 Hours

The anatomy of the penile urethra presents additional challenges when compared to other urethral segments during open stricture surgery particularly because of its unsuitability for excision and primary anastomosis and its relatively deficient corpus spongiosum. Stricture aetiology, location, length and previous surgical intervention remain the primary factors influencing the choice of penile urethroplasty technique. We have identified what we feel are the most important challenges and controversies in penile urethral stricture reconstruction, namely the use of flaps vs grafts, use of skin or oral mucosal tissue for augmentation/substitution and when a single or a staged approach is indicated to give the best possible outcome. The management of more complex cases such as pan-urethral lichen-sclerosus strictures and hypospadias “cripples” is outlined and potential developments for the future are presented.

Core tip: The anatomy of the penile urethra presents additional challenges when compared to other urethral segments. Stricture aetiology, location, length and previous surgical intervention remain the primary factors influencing the choice of penile urethroplasty technique. We described the most important challenges and controversies in penile urethral stricture reconstruction: Use of flaps vs grafts, use of skin or oral mucosal tissue for augmentation/substitution and when a single or a staged approach is indicated to give the best possible outcome. The management of more complex cases (pan-urethral lichen-sclerosus strictures and hypospadias “cripples”) is outlined and potential developments for the future are presented.

- Citation: Campos-Juanatey F, Bugeja S, Ivaz SL, Frost A, Andrich DE, Mundy AR. Management of penile urethral strictures: Challenges and future directions. World J Clin Urol 2016; 5(1): 1-10

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2816/full/v5/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5410/wjcu.v5.i1.1

The treatment of penile urethral strictures is generally more complex when compared with other segments of the urethra by virtue of various anatomical considerations. This is evidenced by the variety of techniques with have been described for reconstruction in this area[1]. Achieving a satisfactory and durable functional outcome (i.e., unobstructed voiding) is the main goal but the cosmetic appearance of the male genitalia also deserves due consideration[2]. Penile shape and length should be preserved and ultimately restored if damaged by injury or scarring from previous surgery[3].

A further concern with penile urethroplasty is erectile function, and in particular, penile shortening and curvature. The risk of transient erectile dysfunction after urethroplasty is clearly described[4]. Loss of penile length and penile curvature are more common after penile urethral surgery[5], particularly when local flaps are used[6].

Mucosal and skin grafts, or local skin flaps, may be considered for penile urethral reconstruction. Consequently the reconstructive surgeon should be skilled at a broad range of techniques and be able to carefully evaluate the benefits and adverse effects of each in individual circumstances[1].

There is a paucity of sound scientific evidence in this field of urology, most of the available literature being based on descriptive case series (not always with homogeneous cohorts of patients) and expert opinions[1,7]. In this paper, we address current practice and the challenges and controversies faced by the reconstructive surgeon in the management of penile urethral strictures. Future developments in this field are also explored.

The penile (or pendulous) urethra is the distal part of the male anterior urethra. It is about 15 cm in length and extends from the external meatus, the narrowest part of the urethra (21-27 F), to the penoscrotal junction where the bulbar segment starts. The penile urethra presents important anatomical differences compared with the bulbar segment[8]. It is surrounded by the thinnest part of the corpus spongiosum in the penile shaft, meaning that it does not provide the best vascular support for a graft. The glans penis, which is the expanded distal end of the corpus spongiosum, surrounds the navicular fossa and external meatus[9]. On the contrary, this rich glanular blood supply provides an ideal vascular bed for successful graft take.

The urethra and the spongiosum are covered by the anterior extension of Buck¡’s fascia, and a layer of dartos areolar tissue (continuation of Colles fascia) that provides blood supply to the penile shaft skin[10]. This dartos tissue is also very well vascularised, making it an ideal graft bed or a pedicle for skin grafts.

Unlike the bulbar urethra, which can be mobilised proximally and distally to allow excision of a stricture and a tension-free primary anastomosis, this is not possible in the penile urethra due to the risk of loss of length and curvature during erection. This means that reconstructive techniques in the penile urethra are limited to augmentation or substitution using free grafts or flaps which in themselves may also result in chordee if used incorrectly. Moreover, pendulous strictures usually tend to be longer[11] (in some series nearly twice as long) than in the bulbar urethra.

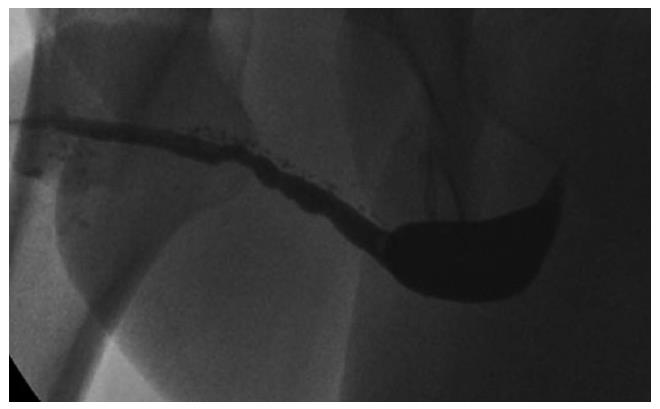

The commonest identifiable cause of penile strictures in young and middle-aged adults is lichen sclerosus (LS) or balanitis xerotica obliterans[12] (Figure 1). This was recently evidenced in a large European cohort of patients[13]. The proposed pathophysiology of penile strictures secondary to LS is that the initial changes occur at the urethral meatus when it becomes involved by the scarring affecting the rest of the glans and prepuce[14]. This atrophic fibrosis can extend proximally, affecting the fossa navicularis and penile urethra, which may be associated with palpable thickening at the level of the strictures. The progression of a distal stricture proximally is related to metaplastic changes due to chronic distension and extravasation of urine with subsequent inflammation of the peri-urethral glands as a result of pressure during voiding. This may be reversible if the obstruction is relieved early[12].

The penile urethra is also susceptible to strictures resulting from infection and traumatic instrumentation during catheterisation or transurethral procedures[15]. These are most commonly located in the navicular fossa and at the peno-scrotal junction[2].

The incidence of each causative factor remains unclear, however in some series it is suggested that fossa navicularis strictures are equally of iatrogenic, idiopathic, and inflammatory origin (including LS) but not the result of external trauma[11]. LS is the most common cause of strictures affecting the entire penile and bulbar urethral segments[16].

Another common occurrence is a recurrent penile urethral stricture following previous failed urethroplasty, particularly in hypospadias-related strictures (Figure 2). Recurrence after hypospadias surgery is the most frequent cause of complex anterior urethral strictures[17] and in some series from tertiary referral centers is the most common indication for staged penile reconstruction[18]. Strictures following failed hypospadias surgery usually occur as a result of early postoperative complications such as infection and consequently become apparent shortly after the surgery. They may however also manifest themselves many years later due to failure of the graft or flap[19].

Stricture aetiology is one of the most important factors determining the choice of management strategy of penile urethral strictures (and indeed all urethral strictures) and particularly the choice of surgical reconstructive procedure[1]. In LS-related strictures the use of mucosal grafts (usually oral but bladder or rectal also possible) is recommended since LS is a skin condition and any skin used for reconstruction is either already, or has the potential to become involved by the disease process[20]. On the other hand, genital skin is suitable for use as a flap or graft for reconstructing the urethra in selected patients with previous hypospadias surgery or instrumentation-related strictures[21].

Flaps or grafts for penile urethroplasty: In 1968, Orandi[22] first reported on reconstruction of the anterior urethra using a pedicled skin flap. The Orandi longitudinal flap provides a long strip of penile skin with a consistent blood supply, adequate to augment the urethral lumen. This urethroplasty technique has proved to be useful for non-obliterative strictures within the penile shaft that are not secondary to LS[1]. Other skin flaps have been described using preputial, penile and scrotal skin[23-25] to treat strictures in any part of the penile urethra. These flaps achieved satisfactory outcomes in selected cases, mainly as an augmentation patch[26] after having excluded LS as a causative factor[27]. It has been shown that such skin flaps, when tubularised, are associated with a higher failure rate; up to 58% in the intermediate-term[26]. In addition, pedicled flaps are associated with other problems. When penile shaft skin is used, patients tend to report unacceptable scars at the donor site incisions, as well as irregularity of the skin caused by raising and rotating the dartos fascia as a pedicle. Furthermore, a degree of penile torsion can occur as a consequence of the pedicle[21]. In cases reconstructed using a circumferential skin tube, “bow-stringing” of the neo-urethra away from the corpora cavernosa can occur, giving the appearance of ventral webbing of the penis[21]. Scrotal skin is associated with the added complication of hair growth resulting in recurrent urethral obstruction by hairballs and stones.

Traditionally penile flaps were preferred to free grafts for penile urethral reconstruction. This was related to the perception of an initial high failure rate of grafts reported in the penile urethra[8]. A graft is only as good as its bed, and unfortunately, the anatomy of the penile spongiosum means that this is not always guaranteed. The rich glanular tissue on the other hand provides a healthy scaffold for grafting, but adequate penile spongiosal tissue and dartos fascia are not always available and thus do not ensure sufficient support for a graft in all patients.

The use of skin grafts for hypospadias surgery has long been described, as a single procedure[28], or as a staged approach[29], when still present, the foreskin has been the preferred graft source[30]. Since the popularisation of oral tissue as a substitution graft for urethroplasty in 1993[31], it has become the material of choice due to certain characteristic properties[32]. Oral mucosa is typically harvested from the cheek but can also be taken from the tongue and inner lip, resulting in a relatively concealed donor site scar and also providing sufficient graft material for almost every length of stricture[33]. A lack of oral tissue for grafting is usually associated with previous failed procedures.

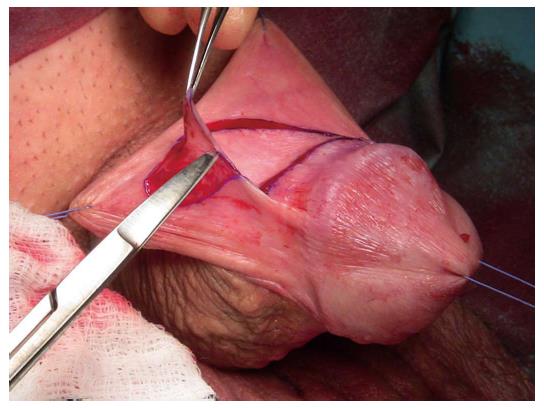

Early reports suggested that outcomes with oral mucosal grafts were better when used as a patch because the failure rates when used as a tubed substitution were high, similar to the previous experience with tubularised flaps. The management of penile urethral strictures changed dramatically with the description of the dorsal free oral mucosal graft technique[34]. Those patients previously treated using a circumferential substitution in one stage with a tubularised local flap began to be managed in a staged fashion using buccal grafts instead[21] (Figure 3).

In summary, the answer to the question “graft vs flap?” needs to be answered on the operating table, each case taken on its own merit, after a careful intraoperative evaluation based on the above-mentioned factors. However as a general rule, one would use a local pedicled flap with its own blood supply preferentially to a free graft in situations where the graft bed is poor, as with severe scarring or following radiotherapy[1].

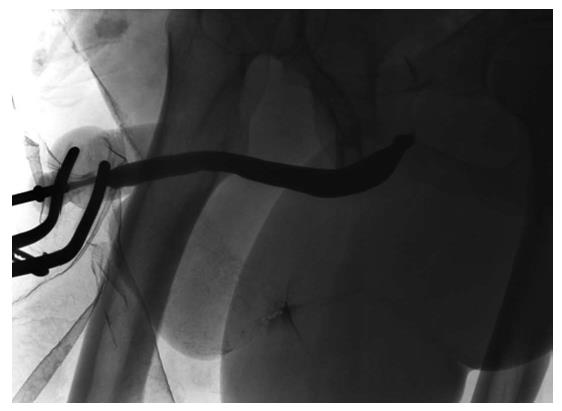

Skin or oral mucosal grafts for augmentation or substitution: Oral mucosa has become the most widely utilised free graft for urethral reconstruction[35]. The advantages of a concealed donor site and availability have already been alluded to. Harvesting the graft is relatively easy and associated with low morbidity[32,36] (Figure 4). Biological and clinical characteristics explain the consistently good results associated with its use since it was first described[37-39]. Oral mucosa is resistant to infection. It usually hosts a variety of microorganisms hence its minimal inflammatory response to organisms[38]. LS does not tend to recur in oral mucosa as it does in skin[20]. Further anatomical advantages are related to a thick elastin-rich epithelium and a highly resilient lamina propria-oral epithelium interface, making it easy to manipulate. A thin and highly vascular lamina propria facilitates inosculation and imbibition, hence improving graft take. These structural features are retained once transplanted to the genital area with histological studies demonstrating that once in the urethra, buccal graft is often indistinguishable from host tissues[40].

The commonest site for free skin grafts is the prepuce[28] (Figure 5), due to its relative ease of harvesting, it being hairless as well as the satisfactory cosmetic appearance of the circumcising incision. Other non-hairy skin donor sites have been suggested such as the medial aspect of the upper arm and the posterior auricular area[28]. Postauricular skin, when used as a full-thickness free graft (Wolfe graft), is associated with a very satisfactory outcome which may be comparable to that obtained using oral mucosa[21]. Facial skin has a particularly dense subdermal plexus, which allows for better graft take and prevents contraction when used as a full-thickness graft. Full thickness skin grafts generally do not take as well as split-skin grafts, but when they do they tend to contract far less (around 20%)[41].

Some authors suggest that the choice of substitution material (oral mucosa vs preputial skin) should be based primarily on surgeon preference and experience[42]. However, several factors need to be taken into consideration including aetiology (skin contraindicated in LS), availability of oral mucosa (such as in revision procedures) and the consequence of any degree of contraction of the grafts particularly chordee, which suggests that split-skin grafts are not suitable for use in the penile urethra.

Single stage or multi-staged penile urethroplasty: When the residual urethral plate is of adequate calibre and the corpus spongiosum, dartos fascia and penile skin are preserved, single stage reconstruction is possible and preferable[18]. Besides avoiding a proximal urethrostomy and its negative impact on quality of life[3,43] for 3-6 mo, the main advantage of a single stage approach is the fewer number of procedures. The staged approach for penile urethral reconstruction is associated with a reported first stage revision rate for graft contracture of between 20% and 31%[18,21,44] ultimately resulting in a three- or more staged procedure.

Several techniques are available for single stage penile urethroplasty. Local skin flaps such as the McAninch preputial flap[24] have been described if the urethral plate can be preserved and no features of LS are evident. The Orandi procedure[22] is recommended by some authors as the best choice for penile urethral augmentation in selected mid-penile short strictures which are not related to LS[1]. Barbagli et al[34] described the dorsal free graft oral mucosal graft technique to augment strictures in the penile urethra in a single stage in addition to the well-known dorsal approach to bulbar urethroplasty.

Another technique for the treatment of distal penile strictures using grafts has been suggested as an evolution of the Snodgrass longitudinal incision of the urethral plate in which an oral mucosal graft is placed as an inlay into the incised urethral plate[45]. Based on the same principle of preserving the native urethral plate when available, Asopa et al[46] described the technique of dorsal augmentation with skin or oral mucosa as a dorsal inlay via a ventral urethrotomy. This procedure is not recommended in cases when the urethral plate is severely scarred, fibrotic or narrowed, but is suitable for less complicated strictures, with the advantage of a less invasive approach through a circumcision incision. Placement of the oral mucosal graft ventrally has also been described in the penile urethra, however due to the lack of adequate spongiosal support, a pseudospongioplasty with dartos tissues is necessary and is not recommended as standard treatment[47].

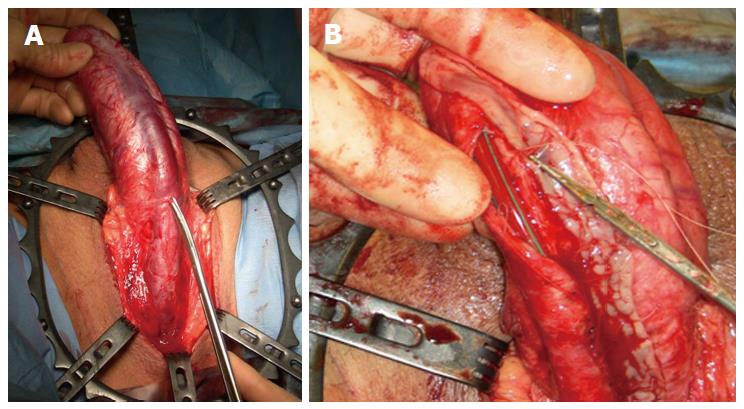

A significant development in the single stage reconstruction of long penile urethral strictures with a salvageable urethral plate is dorso-lateral augmentation using oral mucosal graft via a transperineal approach with invagination of the penis as described by Kulkarni et al[48] (Figure 6). This technique is associated with excellent success rates of up to 92% in the short term (12 mo)[48] and 83.7% in the intermediate term (5 years)[49].

Circumferential reconstruction in a single stage using a tubularised local skin flap is associated with an unacceptably high failure rate[24]. A tubularised repair using oral mucosal grafts in one stage has also been described in the penile urethra but the reported outcomes were similar to previous reports using tubularised skin flaps and are therefore not usually recommended[39]. Consequently those patients in whom complete urethral substitution is necessary due to an unsalvageable urethral plate are preferentially managed via a staged approach using oral mucosal grafts[21]. A stricturotomy is performed and the diseased segment excised. A roof strip is reconstructed using graft during the first stage to produce a neo-urethral plate of adequate width which is then rolled back into a tube in the second stage 3-6 mo later. The success rate of this staged approach is up to 96% in tertiary referral centers[18]. However, complication rates of up to 35% are reported in some series[50].

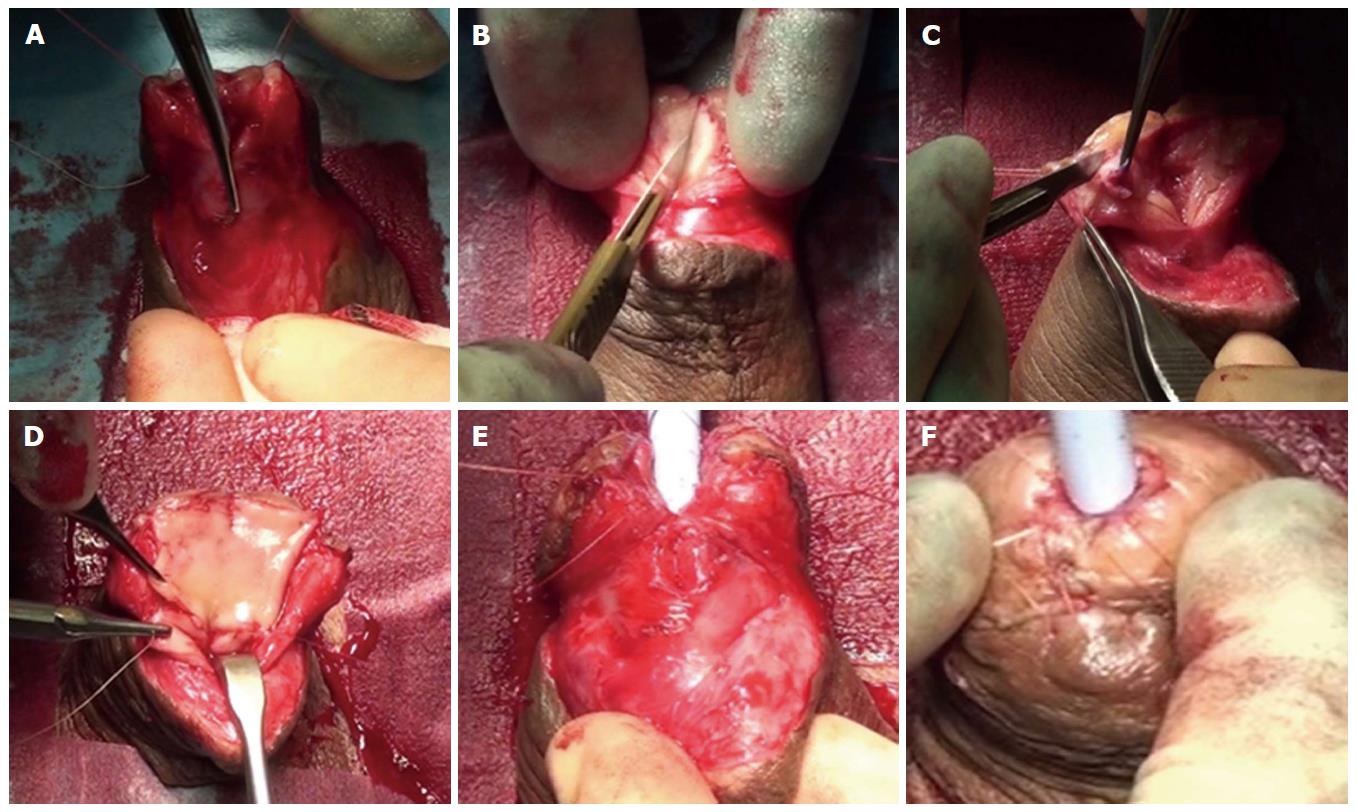

We have recently shown that in selected cases it is possible to excise the spongiofibrosis, create a neo-urethral plate using oral mucosa and tubularise it, all in a single stage (Figure 7). We refer to this as a “two-in-one” stage urethroplasty and is dependent on glans size, spongiosal thickness and adequate dartos to provide support for the graft and allow enough tissue mobility for tension-free retubularisation. Previously unoperated, LS-related navicular fossa and distal penile urethral strictures are most suitable for this technique which is associated with a success rate of 90% at a mean follow-up of 16.2 mo[51].

In some cases, such as following failed hypospadias surgery, absence of an adequate spongiosum or lack of dartos and/or penile skin, a staged approach is recommended[52] for the reasons described above. However, as with all urethroplasties, but particularly in the penile urethra, it is not always possible to predict the quality of the local tissues or the residual urethral plate available for reconstruction prior to the surgery. Consequently, in our practice, patients undergoing penile urethroplasty are consented for either approach. The decision as to whether or not a single staged approach should be avoided in favour of a staged procedure is always based on a thorough intraoperative evaluation by an experienced reconstructive surgeon who is able to predict the likelihood of success and complications of either approach[21].

Management of complex cases: Penile urethral strictures range from short strictures (Figure 8) in which the urethral plate is preserved and which are relatively easily treated by augmentation techniques, to complete obliteration of the entire length of the penile urethra due to severe LS or failed hypospadias surgery (Figure 9). Management of the latter, especially those after previous failed attempts at reconstruction, presents additional challenges. The literature relating to these complex cases is sparse and does not provide reliable guidelines[42], particularly because of the heterogeneity of this group of patients. Treatment of such complex strictures commonly involves excision of the original obliterated skin tube and substitution of the entire diseased segment. These cases are often complicated further by urethrocutaneous fistulae (Figure 10), penile curvature and loss of penile length. In fact, in some series of penile urethroplasty[17], the reconstruction was restricted solely to the urethra in only 25.5% of the cases, with the rest requiring additional procedures such as correction of chordee or penile lengthening. A staged approach is preferable in these cases[29].

Such surgery, involving reconstruction of the urethra and the corpora cavernosa, should be performed by experienced surgeons in high volume, tertiary referral centres to ensure the best cosmetic and functional outcome for these patients[53]. The best outcome in these patients is achievable during the first reconstructive procedure, with salvage surgery becoming increasingly complex and associated with an increased failure rate.

Not all complex penile urethral strictures are amenable to reconstruction[54] and indeed some patients may not be keen on having further surgical intervention or may not be medically fit for major surgery. In these patients a regime of interval urethral dilatation may be feasible to preserve urethral voiding and adjunctive self-dilatation may prolong the interval between recurrence[55]. Many find this unsustainable due to pain, bleeding and recurrent infections and is generally associated with a poor quality of life[56]. Perineal urethrostomy, though not immediately acceptable to many, does present a feasible salvage treatment option in these patients with a reasonably good functional outcome and minimal complications[57].

Future directions: Penile urethroplasty has evolved since first attempts at reconstruction using foreskin tubes[28] or a staged approach using penile skin[58]. An increased understanding of the pathophysiology of LS together with the high recurrence rate if skin was used for reconstruction led to the recommended use of oral mucosal grafts in LS strictures[20]. However, to date, very little benefit has been achieved with non-surgical treatment options[59]. Further research in this field may lead to the development of ways and means of stabilising or even inducing remission in this recalcitrant skin pathology.

The main limitations of current penile urethroplasty techniques are the frequent requirement of a staged procedure with its associated patient inconvenience and 20%-31% incidence of graft failure following the first stage requiring further revision surgery prior to retubularisation. Lack of available oral mucosa in full-length penile strictures, particularly in revision cases, presents additional problems. The inability to simply excise obliterative strictures and perform an end-to-end anastomosis means that substitution techniques become necessary however tubularised substitution is inherently associated with a high failure rate.

Extensive research has been carried out in the fields of biomaterials, regenerative medicine and tissue engineering in order to try and overcome some of the limitations related to current penile urethral stricture management outlined above. The primary aim has been to generate a graft with properties similar to oral mucosa but which is readily available “off the shelf”, in unlimited quantities and with no morbidity associated with graft harvesting. Despite significant advances, the ideal biomaterial or composite graft has not yet been identified for use in routine clinical practice[60].

Numerous animal models and clinical studies have tested a variety of engineered urethral substitutes over the past 30 years. Both natural and synthetic matrices, biodegradeable and non-absorbable, seeded and unseeded, have been studied. Unseeded, “off the shelf” tubularised grafts have only been successful in replacing urethral defects less than 0.5 cm in length due to failure of epithelialisation of longer grafts from healthy surrounding tissues[61]. Unseeded grafts used as a patch in an onlay or inlay fashion have shown better results in clinical trials[62,63]. Unfortunately this has not been replicated in longer strictures. One hundred percent failure rates were reported in strictures longer than 4 cm[64]. Suboptimal results were demonstrated in patients who have had previous failed urethroplasties or those with an unhealthy vascular bed[65], two patient populations in whom alternatives to conventional substitution materials are generally sought.

In order to treat longer strictures cellularised scaffolds seem to be necessary since graft survival would be independent of epithelial cell ingrowth. Tubularised seeded grafts have shown positive results in a canine model[66] and in the only clinical trial to date[67] albeit both in the bulbar or posterior urethra. A recent review on tissue engineered oral mucosa[68] has shown this to be a “promising alternative” but requires long-term large cohort clinical trials before being advocated for widespread use. Moreover, cellularised grafts require a source of cells for seeding, are laborious, time-consuming and expensive to manufacture[69] which defeat the purpose of having a readily available off the shelf tissue substitute.

Even though the ideal tissue engineered urethral substitute may be several years away, what can and should certainly be addressed right away is the awareness amongst urological surgeons that urethral reconstruction is a highly specialised discipline and should only be undertaken by experienced surgeons in high volume tertiary units in order to ensure the best possible outcome for patients[70] particularly given the fact that the first procedure is usually the one with the best results.

Penile urethral strictures present a therapeutic challenge to the reconstructive urologist and are also associated with a significant negative impact on patient quality of life, many of them starting off with problems in infancy or adolescence and progressing into adult life, often requiring multiple surgical interventions in the process. Short, primary strictures are usually relatively easily reconstructable using oral mucosal grafts or skin flaps in a single or multi-staged approach with high rates of success. The major challenges lie with those patients having extensive LS-related strictures or “hypospadias cripples” for whom current urethroplasty techniques are not always possible or feasible. These commonly end up being managed by repeated endoscopic intervention, self-dilatation or a perineal urethrostomy, often after having undergone multiple failed attempts at urethral reconstruction.

An abundance of penile urethroplasty techniques have been described over the years bearing witness to the difficulty in dealing with this condition. All are however based on stricture aetiology, length, location and previous surgical intervention. It is up to the reconstructive surgeon to carefully evaluate the anatomy of the stricture and supporting tissues intraoperatively and only then decide which technique would give the greatest likelihood of success in any given circumstance. Hence the importance of centralisation of urethroplasty services to high volume units with expertise in a braod range of techniques.

One hopes that ongoing research will give rise to therapeutic modalities which can alter the underlying pathological processes in LS and that advances in restorative medicine would lead to the generation of novel, biocompatible and commercially viable urethral substitutes.

P- Reviewer: Kilinc M, Naselli A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Andrich DE, Mundy AR. What is the best technique for urethroplasty? Eur Urol. 2008;54:1031-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Armenakas NA, McAninch JW. Management of fossa navicularis strictures. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:477-484. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Barbagli G, De Angelis M, Palminteri E, Lazzeri M. Failed hypospadias repair presenting in adults. Eur Urol. 2006;49:887-894; discussion 895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Blaschko SD, Sanford MT, Cinman NM, McAninch JW, Breyer BN. De novo erectile dysfunction after anterior urethroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2013;112:655-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bubanj TB, Perovic SV, Milicevic RM, Jovcic SB, Marjanovic ZO, Djordjevic MM. Sexual behavior and sexual function of adults after hypospadias surgery: a comparative study. J Urol. 2004;171:1876-1879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Kim KR, Suh JG, Paick JS, Kim SW. Surgical outcome of urethroplasty using penile circular fasciocutaneous flap for anterior urethral stricture. World J Mens Health. 2014;32:87-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Barbagli G, Morgia G, Lazzeri M. Retrospective outcome analysis of one-stage penile urethroplasty using a flap or graft in a homogeneous series of patients. BJU Int. 2008;102:853-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wessells H, McAninch JW. Use of free grafts in urethral stricture reconstruction. J Urol. 1996;155:1912-1915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Humphrey PA. Genital skin and urethral anatomy. Current clinical urology: Urethral reconstructive surgey. Totowa: Humana Press 2008; 1-8. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Dwyer ME, Salgado CJ, Lightner DJ. Normal penile, scrotal, and perineal anatomy with reconstructive considerations. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25:179-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fenton AS, Morey AF, Aviles R, Garcia CR. Anterior urethral strictures: etiology and characteristics. Urology. 2005;65:1055-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mundy AR, Andrich DE. Urethral strictures. BJU Int. 2011;107:6-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lumen N, Hoebeke P, Willemsen P, De Troyer B, Pieters R, Oosterlinck W. Etiology of urethral stricture disease in the 21st century. J Urol. 2009;182:983-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Andrich DE, Mundy AR. Substitution urethroplasty with buccal mucosal-free grafts. J Urol. 2001;165:1131-1133; discussion 1133-1134. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Meeks JJ, Barbagli G, Mehdiratta N, Granieri MA, Gonzalez CM. Distal urethroplasty for isolated fossa navicularis and meatal strictures. BJU Int. 2012;109:616-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Barbagli G, Mirri F, Gallucci M, Sansalone S, Romano G, Lazzeri M. Histological evidence of urethral involvement in male patients with genital lichen sclerosus: a preliminary report. J Urol. 2011;185:2171-2176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Barbagli G, Perovic S, Djinovic R, Sansalone S, Lazzeri M. Retrospective descriptive analysis of 1,176 patients with failed hypospadias repair. J Urol. 2010;183:207-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Andrich DE, Greenwell TJ, Mundy AR. The problems of penile urethroplasty with particular reference to 2-stage reconstructions. J Urol. 2003;170:87-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tang SH, Hammer CC, Doumanian L, Santucci RA. Adult urethral stricture disease after childhood hypospadias repair. Adv Urol. 2008;150315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Venn SN, Mundy AR. Urethroplasty for balanitis xerotica obliterans. Br J Urol. 1998;81:735-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Greenwell TJ, Venn SN, Mundy AR. Changing practice in anterior urethroplasty. BJU Int. 1999;83:631-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Orandi A. One-stage urethroplasty. Br J Urol. 1968;40:717-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mundy AR, Stephenson TP. Pedicled preputial patch urethroplasty. Br J Urol. 1988;61:48-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | McAninch JW. Reconstruction of extensive urethral strictures: circular fasciocutaneous penile flap. J Urol. 1993;149:488-491. [PubMed] |

| 26. | McAninch JW, Morey AF. Penile circular fasciocutaneous skin flap in 1-stage reconstruction of complex anterior urethral strictures. J Urol. 1998;159:1209-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Virasoro R, Eltahawy EA, Jordan GH. Long-term follow-up for reconstruction of strictures of the fossa navicularis with a single technique. BJU Int. 2007;100:1143-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Humby G. A one-stage operation for hypospadias. Br J Urol. 1941;29:84-92. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bracka A. Hypospadias repair: the two-stage alternative. Br J Urol. 1995;76 Suppl 3:31-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bracka A. A versatile two-stage hypospadias repair. Br J Plast Surg. 1995;48:345-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | el-Kasaby AW, Fath-Alla M, Noweir AM, el-Halaby MR, Zakaria W, el-Beialy MH. The use of buccal mucosa patch graft in the management of anterior urethral strictures. J Urol. 1993;149:276-278. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Wood DN, Allen SE, Andrich DE, Greenwell TJ, Mundy AR. The morbidity of buccal mucosal graft harvest for urethroplasty and the effect of nonclosure of the graft harvest site on postoperative pain. J Urol. 2004;172:580-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Simonato A, Gregori A, Lissiani A, Galli S, Ottaviani F, Rossi R, Zappone A, Carmignani G. The tongue as an alternative donor site for graft urethroplasty: a pilot study. J Urol. 2006;175:589-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Barbagli G, Selli C, Tosto A, Palminteri E. Dorsal free graft urethroplasty. J Urol. 1996;155:123-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mangera A, Patterson JM, Chapple CR. A systematic review of graft augmentation urethroplasty techniques for the treatment of anterior urethral strictures. Eur Urol. 2011;59:797-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Barbagli G, Fossati N, Sansalone S, Larcher A, Romano G, Dell’Acqua V, Guazzoni G, Lazzeri M. Prediction of early and late complications after oral mucosal graft harvesting: multivariable analysis from a cohort of 553 consecutive patients. J Urol. 2014;191:688-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Dubey D, Vijjan V, Kapoor R, Srivastava A, Mandhani A, Kumar A, Ansari MS. Dorsal onlay buccal mucosa versus penile skin flap urethroplasty for anterior urethral strictures: results from a randomized prospective trial. J Urol. 2007;178:2466-2469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Filipas D, Fisch M, Fichtner J, Fitzpatrick J, Berg K, Störkel S, Hohenfellner R, Thüroff JW. The histology and immunohistochemistry of free buccal mucosa and full-skin grafts after exposure to urine. BJU Int. 1999;84:108-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Venn SN, Mundy AR. Early experience with the use of buccal mucosa for substitution urethroplasty. Br J Urol. 1998;81:738-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Markiewicz MR, Lukose MA, Margarone JE, Barbagli G, Miller KS, Chuang SK. The oral mucosa graft: a systematic review. J Urol. 2007;178:387-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | El-Sherbiny MT, Abol-Enein H, Dawaba MS, Ghoneim MA. Treatment of urethral defects: skin, buccal or bladder mucosa, tube or patch? An experimental study in dogs. J Urol. 2002;167:2225-2228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Barbagli G, Sansalone S, Djinovic R, Romano G, Lazzeri M. Current controversies in reconstructive surgery of the anterior urethra: a clinical overview. Int Braz J Urol. 2012;38:307-316; discussion 316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Levine LA, Strom KH, Lux MM. Buccal mucosa graft urethroplasty for anterior urethral stricture repair: evaluation of the impact of stricture location and lichen sclerosus on surgical outcome. J Urol. 2007;178:2011-2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Dubey D, Sehgal A, Srivastava A, Mandhani A, Kapoor R, Kumar A. Buccal mucosal urethroplasty for balanitis xerotica obliterans related urethral strictures: the outcome of 1 and 2-stage techniques. J Urol. 2005;173:463-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Hayes MC, Malone PS. The use of a dorsal buccal mucosal graft with urethral plate incision (Snodgrass) for hypospadias salvage. BJU Int. 1999;83:508-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Asopa HS, Garg M, Singhal GG, Singh L, Asopa J, Nischal A. Dorsal free graft urethroplasty for urethral stricture by ventral sagittal urethrotomy approach. Urology. 2001;58:657-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Cordon BH, Zhao LC, Scott JF, Armenakas NA, Morey AF. Pseudospongioplasty using periurethral vascularized tissue to support ventral buccal mucosa grafts in the distal urethra. J Urol. 2014;192:804-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kulkarni S, Barbagli G, Sansalone S, Lazzeri M. One-sided anterior urethroplasty: a new dorsal onlay graft technique. BJU Int. 2009;104:1150-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kulkarni SB, Joshi PM, Venkatesan K. Management of panurethral stricture disease in India. J Urol. 2012;188:824-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Snodgrass W, Elmore J. Initial experience with staged buccal graft (Bracka) hypospadias reoperations. J Urol. 2004;172:1720-1724; discussion 1724. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Campos F, Bugeja S, Frost A, Fes E, Ivaz S, Andrich DE, Mundy AR. PD14-11 Single stage versus classical staged approach for penile urethral strictures. J Urol. 2015;193:e322-e323. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Lazzeri M, Guazzoni G. Anterior urethral strictures. BJU Int. 2003;92:497-505. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Perovic S, Barbagli G, Djinovic R, Sansalone S, Vallasciani S, Lazzeri M. Surgical challenge in patients who underwent failed hypospadias repair: is it time to change? Urol Int. 2010;85:427-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kulkarni S, Barbagli G, Kirpekar D, Mirri F, Lazzeri M. Lichen sclerosus of the male genitalia and urethra: surgical options and results in a multicenter international experience with 215 patients. Eur Urol. 2009;55:945-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Jackson MJ, Veeratterapillay R, Harding CK, Dorkin TJ. Intermittent self-dilatation for urethral stricture disease in males. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD010258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Lubahn JD, Zhao LC, Scott JF, Hudak SJ, Chee J, Terlecki R, Breyer B, Morey AF. Poor quality of life in patients with urethral stricture treated with intermittent self-dilation. J Urol. 2014;191:143-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Myers JB, McAninch JW. Perineal urethrostomy. BJU Int. 2011;107:856-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Johanson B. Reconstruction of the male urethra in strictures: application of the buried intact epithelium technic. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1953;176:1-103. |

| 59. | Stewart L, McCammon K, Metro M, Virasoro R. SIU/ICUD Consultation on Urethral Strictures: Anterior urethra-lichen sclerosus. Urology. 2014;83:S27-S30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Atala A, Bauer SB, Soker S, Yoo JJ, Retik AB. Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet. 2006;367:1241-1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1415] [Cited by in RCA: 1175] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Dorin RP, Pohl HG, De Filippo RE, Yoo JJ, Atala A. Tubularized urethral replacement with unseeded matrices: what is the maximum distance for normal tissue regeneration? World J Urol. 2008;26:323-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Fiala R, Vidlar A, Vrtal R, Belej K, Student V. Porcine small intestinal submucosa graft for repair of anterior urethral strictures. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1702-1708; discussion 1708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Palminteri E, Berdondini E, Colombo F, Austoni E. Small intestinal submucosa (SIS) graft urethroplasty: short-term results. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1695-1701; discussion 1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Palminteri E, Berdondini E, Fusco F, De Nunzio C, Salonia A. Long-term results of small intestinal submucosa graft in bulbar urethral reconstruction. Urology. 2012;79:695-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | el-Kassaby A, AbouShwareb T, Atala A. Randomized comparative study between buccal mucosal and acellular bladder matrix grafts in complex anterior urethral strictures. J Urol. 2008;179:1432-1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Orabi H, AbouShwareb T, Zhang Y, Yoo JJ, Atala A. Cell-seeded tubularized scaffolds for reconstruction of long urethral defects: a preclinical study. Eur Urol. 2013;63:531-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Raya-Rivera A, Esquiliano DR, Yoo JJ, Lopez-Bayghen E, Soker S, Atala A. Tissue-engineered autologous urethras for patients who need reconstruction: an observational study. Lancet. 2011;377:1175-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Osman NI, Hillary C, Bullock AJ, MacNeil S, Chapple CR. Tissue engineered buccal mucosa for urethroplasty: progress and future directions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;82-83:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Mangera A, Chapple CR. Tissue engineering in urethral reconstruction--an update. Asian J Androl. 2013;15:89-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Santucci RA. Should we centralize referrals for repair of urethral stricture? J Urol. 2009;182:1259-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |