Published online Nov 24, 2015. doi: 10.5410/wjcu.v4.i3.108

Peer-review started: May 20, 2015

First decision: August 19, 2015

Revised: October 17, 2015

Accepted: November 13, 2015

Article in press: November 17, 2015

Published online: November 24, 2015

Processing time: 193 Days and 23.1 Hours

Continuous bladder irrigation (CBI) is commonly prescribed after certain prostate surgeries to help prevent the clot formation and retention that are frequently associated with these sometimes hemorrhagic surgeries. However, it remains unknown how effective CBI is in preventing clot formation/catheter blockage because these complications still frequently occur in the presence of CBI. On the other hand, the outcome of prostate surgeries has significantly improved over the years, and these surgeries have generally become much safer and, in many hands, less hemorrhagic. Newer surgical options such as holmium laser enucleation of the prostate with associated improved hemorrhagic control have also been introduced, further creating the opportunity to eliminate CBI. Furthermore, there is a lack of review articles on CBI. Hence, this article will review the evolution and contemporary role of CBI in prostate surgeries. To eliminate CBI after prostate surgeries, it is important to achieve good hemostasis during the surgeries. Having in place a policy of non-irrigation after prostate surgeries is also important if less CBI is to be the norm. A non-irrigation policy will hopefully help reduce those cases of CBI prescribed out of long-standing surgical tradition while allowing for cases prescribed out of compelling necessity. The author’s policy of a consistent non-CBI during prostate surgeries over the last 9 years will be highlighted.

Core tip: Continuous bladder irrigation (CBI) has been part and parcel of some prostate surgeries and might have been more relevant during the era of unpredictable hemostatic control. Hemostatic control during prostate surgeries has significantly improved, and new technologies with associated improved hemostasis have been introduced. Hence, CBI can be safely avoided in most prostate surgeries, especially when good hemostasis has been achieved and a policy to pursue the non- CBI pathway is in place.

- Citation: Okorie CO. Is continuous bladder irrigation after prostate surgery still needed? World J Clin Urol 2015; 4(3): 108-114

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2816/full/v4/i3/108.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5410/wjcu.v4.i3.108

Continuous bladder irrigation (CBI) can be defined as an uninterrupted and simultaneous infusion and drainage of the bladder with fluid. CBI is commonly used after some surgical procedures on the prostate [transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), open prostatectomy] and also on the bladder [transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT)]. Post-operative CBI is so commonly used that it remains a standard recommendation in urologic textbooks and journal articles[1-9] and is also a component of practical nursing training[10-14]. Over the years, CBI was developed and used as a valuable method of managing hemorrhage and clot formation after prostate surgeries[15-24]. However, it remains unknown how effective CBI is in preventing clot formation/catheter blockage because these complications still frequently occur in the presence of CBI[25]. Furthermore, there are no evidence-based guidelines for bladder irrigation strategies. On the other hand, the outcome of prostate surgeries (TURP and open prostatectomy) has significantly improved over these years, and these surgeries have generally become much safer and, in many hands, less hemorrhagic[6,25-37]. As such, it becomes pertinent to review the contemporary role of CBI in prostate surgeries, especially in TURP and open prostatectomy where CBI is most commonly used, but also in holmium enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP), which is currently considered the endourologic equivalent of open prostatectomy. Of note, there is a lack of review articles on CBI, and it is hoped that this article will help fill that gap.

The evolution of bladder drainage and subsequently that of bladder irrigation is closely related to the problem of hemorrhage and clot formation associated with surgeries involving the prostate and also the bladder. The concept of bladder drainage and bladder irrigation has evolved over many years and has especially been part and parcel of surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Byrne[16] found that a significant percentage of deaths that occur secondary to hemorrhage after prostatectomy can be attributed to inadequate catheter drainage of the bladder. According to Tinckler[19], apart from general patient management, patient care following prostatectomy is mainly concerned with ensuring uninterrupted drainage of urine and blood from the lower urinary tract until normal hemostasis is attained, avoiding accumulation of blood and clot retention. The frequent and frustrating experience of preventing catheter blockage is of much burden to both the patient and the medical staff, but most especially to the nurses who are more directly involved in monitoring the drainage function of these catheters. Lowthian P expressed this frustration in a graphic letter to the Editor of BJU[38]. Hence, ensuring adequate catheter drainage has always been an integral component of surgical procedures on the prostate and bladder.

Postoperative drainage of the bladder has been effected through the perineum, bladder and urethra. Fuller[39] inserted a tube through the perineum into the bladder and irrigated the bladder with hot water to aid hemostasis and wash out blood clots. Cabot[40] described a double glass tube that was inserted suprapubically and used to irrigate and drain the bladder using water. Other suprapubic drains of interest include those of Herman et al[41]. According to McEachern[42], the introduction of the Harris prostatectomy and development of transurethral resection of the prostate helped bring to the frontline the enormity associated with the care of indwelling urethral catheters, especially the necessity of frequent bladder flushing for any questionable function or obvious signs and symptoms of blockage. The frequency of intermittent flushing of the bladder through these catheters during the first 24 h after prostatectomy could be on hourly interval[43] if not more frequent and undoubtedly can be overwhelming for both the patients and medical personnel. Hence, exploring a method of CBI that will eliminate or reduce the frequency of intermittent flushing of the bladder could only have been a welcomed addition to the postoperative management of these patients at that point in time.

Early publications mentioning methods of CBI in the literature include those of Loughnane[44] and Foley in Wilde et al[45]. However, a more precise description of a method of continuous bladder irrigation after prostate surgery was that of Adams[46]. Adams[46] described a “third ureter in prostatectomy”, highlighting the need of a continuous inflow of fluid into the bladder cavity, contrary to the option of intermittent washout of the bladder. This publication describes the use of a suprapubic tube connected to a reservoir of antiseptic solution for a continuous inflow of this solution into the bladder and as such, the tube serves as an additional source of fluid apart from the natural source from the kidneys through the two ureters - hence the description by the author of this additional source of fluid as a “third ureter”. Further developments in the use of continuous irrigation have been numerous and variable[16-24]. Currently, the CBI procedure is commonly performed using normal saline and a three-way Foley catheter[1,11,12,47].

Post-operative bladder irrigation has been an integral part of a number of surgical procedures on the bladder and prostate and is still widely practiced and recommended in textbooks and journal articles[1-14].The reasons for advocating CBI after prostate surgery include the following: (1) prevention of clot formation and retention; (2) maintenance of the patency of the drainage catheter lumen; (3) flushing out of small clots before they become larger; and (4) bleeding control[20]. In contrast, those who advocate not using CBI after prostate surgery[25,37,48-52] give the following reasons: (1) less workload on the medical staff; (2) less financial cost to the patient; (3) easier calculation of urine output; (4) reduced risk of bladder rupture in the presence of a blocked urethral catheter; (5) urethral catheter blockage and clot retention still frequently occur even in the presence of CBI; (6) avoidance of confinement of the patient to the bed for CBI; and (7) avoidance of suprapubic pain/discomfort.

To eliminate CBI, varying approaches have been used by different authors. The various approaches to elimination of CBI can be divided into: (1) non-surgical; and (2) surgical.

Non-surgical: Use of diuretics: Some advocates of no irrigation effect CBI through the use of diuretics but without the use of an external irrigant. This concept of CBI that avoids external irrigants relies instead on the administration of high intravenous fluid in combination with diuretics that ultimately increases urine flow through the bladder[48-50,52,53]. The concern with this approach is the risk of metabolic disturbance and fluid overload in these patients, who are predominantly elderly[53].

Surgical: As mentioned in the historical background section, CBI has traditionally been intertwined with the problem of significant hemorrhage/clot formation associated with prostatic surgery. Hence, the focus of surgical modifications towards possible elimination of CBI has focused on improving hemostasis during prostate surgery.

For suprapubic prostatectomy, the approaches towards achieving better hemostasis have been variable, but in contemporary practice have commonly included packing the prostatic cavity and sutural methods of hemostasis[41,54,55]. Generally, packing the prostatic fossa has been associated with mixed success in controlling hemorrhage with a not uncommon need to periodically re-pack a few hours following surgery due to persistent bleeding. Even in cases in which packing helped achieve control of hemostasis, periodic drainage of urine to the exterior through the drainage site and later removal of the gauze pack that can be painful and might also provoke re-bleeding due to dislodgement of the already formed clot on the prostatic fossa has decreased the appeal of this method. To avoid pain and also to be prepared for possible re-packing, many urologists remove the gauze pack in the operating room with the use of anesthesia and in doing so, subject the involved patients to another trip to the operating room[41]. However, some contemporary authors have reported a more successful outcome of prostatic fossa packing with lower complication rates[56,57]. Review of some of these contemporary papers on prostatic fossa packing that reported good hemostatic control, however, showed that CBI was still routinely used[56].

Suturing the bleeding points or areas of anatomical entrance of arterial branches supplying the hyperplastic prostatic tissues is presently the dominant method of achieving hemostasis during suprapubic prostatectomy. Lower[58] and Harris[59] were among the early pioneers and advocates of sutural hemostasis. There has been a persistent effort among these early surgeons to place sutures at areas of the bladder neck where it was thought they would help achieve maximum hemostasis. Harris[59], in addition to reformation of the prostatic fossa, placed hemostatic sutures at the 5 o’clock and 7 o’clock positions of the bladder neck. In his surgical description of sutural hemostasis during suprapubic prostatectomy, Silverton[60] prefers to place “U” shaped or mattress sutures essentially to include the areas between the 3 o’clock and 5 o’clock as well as between the 7 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions. Another very significant development in the evolution of sutural hemostasis is the concept of separating the prostatic fossa from the bladder neck. This significant modification has led to a distinct direction of sutural hemostasis with many reported good surgical outcomes. Lower[58] and Harris[59] were the early pioneers that described the method of separating the prostatic fossa from the bladder neck using absorbable sutures as an approach to control hemorrhage associated with suprapubic prostatectomy. Further development of the concept of separation of the prostatic fossa from the bladder neck gave rise to the use of removable purse string sutures[61]. Malament[62] used this approach of removable purse string sutures in separating the prostatic fossa from the bladder neck and noted a significant reduction in post suprapubic prostatectomy bleeding. Other authors using the Malamet technique[34,63,64] documented good results and hence, the Malamet technique has continued to be an important option of surgical hemostasis during suprapubic prostatectomy. In a further modification of the removable purse string technique, Denis[65] additionally placed a drain in the prostatic fossa; according to the author, placement of the drain led to retraction and tamponade of the fossa and through this combination of suturing and drain placement, improved hemostasis was achieved. Contemporary use of the removable purse string technique has led to significant improvement in hemostasis; however, some of the complications that have historically plagued the technique of separating the prostatic fossa from the bladder neck, such as bladder neck stenosis/urethral stricture, periodic need for blood transfusion, clot retention and catheter blockage, have variably persisted. With this approach, there has occasionally been the need to return to operating room to remove fragments of broken purse string suture or evacuate clots, although these complications might be dependent on the surgeon or medical center[34,66]. Most contemporary authors reporting on the removable bladder neck purse string suture technique used CBI[65,67], whereas some others used intermittent bladder irrigation[34,66] and a few did not irrigate[68].

For TURP, improvements in resectoscopes, resectoscope loops, optics, energy sources, and experience of the operating surgeon have all contributed to reducing the bleeding risks historically associated with TURP[36,69]. TURP has significantly evolved over the years to the point where some authors presently perform TURP on “day-case” basis[32]. However, even for these day-case TURP with reported meticulous hemostasis, CBI was still routinely performed[32].

Another important alternative to TURP and open prostatectomy with associated better hemostasis during prostate surgery is the Holmium enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP). HoLEP is currently being acclaimed as a true endourologic equivalent of open prostatectomy, especially for large prostate glands. Blood loss is significantly reduced compared to TURP and open prostatectomy, and as such, HoLEP is associated with less or no need for blood transfusion[70-72]. This improved hemostatic control is an important factor in avoiding/minimizing CBI and can also be induced from the relatively low rate of CBI with the HoLEP technique[70,73].

In contemporary practice, the most commonly recommended method of sutural hemostasis for suprapubic prostatectomy has remained the application of hemostatic stitches to the 5 and 7 o’clock positions of the bladder neck[1,74]. This method of hemostasis can be effective in controlling hemorrhage in some of these procedures; however, in many other cases, significant hemorrhage and the need for blood transfusion has remained a persistent problem[74] further fueling the continued search of a more effective method of hemostasis during suprapubic prostatectomy. Furthermore, CBI remains virtually a routine practice with this approach of application of hemostatic stitches to the 5 and 7 o’clock positions of the bladder neck[1].

It would probably be an overstatement to attribute complete elimination of CBI for suprapubic prostatectomy to any single sutural hemostatic technique. In the author’s opinion, elimination of CBI involves a combination of factors that includes, among other factors: appropriate patient selection, meticulous surgical technique especially during enucleation of prostatic adenomas, adequate sutural hemostasis, having in place a non-irrigation policy and proper Foley catheter selection[25,37].

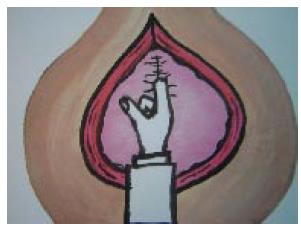

The author’s modified method of surgical hemostasis during suprapubic prostatectomy[25,37] is based on the following intent: To maximize hemostatic suturing of all arterial branches that enter into the bladder neck and proximal prostatic capsule, in contrast to the commonly practiced application of stitches to the 5 and 7 o’clock positions, and at the same time to avoid excessive narrowing of the bladder neck that could compromise the bladder neck lumen and consequently lead to prostatic fossa or bladder neck stenosis. Following a meticulous enucleation of the prostatic adenomas (probably the most important stage of the surgery in the author’s opinion), the modified bladder neck repair/sutural hemostasis[25,37] consists of a running suture from the 1 o’clock position to the 11 o’clock position, suturing the bladder neck edge to the prostatic capsule with 2-0 polyglactin suture (Figure 1) and additional interrupted sutures applied vertically starting from the 12 o’clock position downwards to narrow the bladder neck up to the diameter of the surgeon’s index finger (Figure 2). With the index finger in the bladder neck, a 22 or 24 two-way urethral Foley catheter is inserted and guided into the bladder lumen. The balloon of the Foley catheter, which remains in the bladder lumen, is inflated to a minimum of 30 mL and placed on mild traction by tying a piece of gauze to the catheter and pushing it gently against the meatus for approximately two hours and additionally by taping the catheter to the thigh under moderate traction until the following morning with an adhesive strapping. In this way, the catheter balloon is gently pressed against the bladder neck, augmenting hemostasis and reducing reflux of blood from the prostatic fossa back to the bladder. The anterior bladder wall defect and the remainder of the incisional wound layers are closed without use of suprapubic catheters or surgical drains. Post-operative bladder irrigation is not needed and is not utilized with this approach. With these modifications, none of our patients has received a blood transfusion or CBI over the last 9 years.

Over the years, the surgical outcomes of TURP and suprapubic prostatectomy have definitely improved[6,25-31,33-37]. This can be attributed to a number of factors including improvements in surgical techniques and instruments. The questions then become how often is CBI used out of a long-existing surgical tradition, and in contemporary practice, how often is CBI still needed due to actual necessity? These are important questions considering the fact that authors that have reported good hemostatic control in their surgeries still continued to use CBI[56,67,69]. Although CBI is typically performed without undue complications, significant complications do occur[75] and moreover, the challenges that come with monitoring the CBI method can be overwhelming, especially in understaffed hospitals across developing countries. If postoperative CBI is to be avoided, then the key to success probably not only depends on a number of factors including meticulous surgical technique, very good hemostatic control, and use of good quality drainage catheters, but also on the implementation of a non-irrigation policy. Furthermore, it must be emphasized that the pursuit of good hemostasis should always be balanced with that of avoiding complications such as bladder neck stenosis, which can occur, for instance, in cases of significant narrowing of the bladder neck in suprapubic prostatectomy; however, this complication was more common in the older series of suprapubic prostatectomy than in more contemporary series[62,76].

Since 2006, it has been possible for this author to completely avoid CBI in cases of TURP and open prostatectomy. It is important to mention that even in rare cases of significant bleeding, it has been possible to eliminate CBI by not being in a hurry to implement this irrigation. It is also important to remember that two-way catheters used for bladder drainage have a larger drainage lumen compared to three-way catheters of the same size[52]. Hence, with adequate surgical hemostasis and with the strong aim to pursue a non-irrigation policy, it is very much feasible to avoid CBI in most cases of prostate surgery.

It can then be proposed that the key to eliminating bladder irrigation involves achieving effective surgical hemostasis and maximally reducing the presence of blood in the bladder lumen by reducing the reflux of blood from the prostatic fossa back to the bladder lumen and enhancing the immediate efflux of blood out of the bladder lumen by using good drainage catheters such as an appropriately sized two-way catheter.

However, it is very important to emphasize that changing the mindset/attitude of the surgeon towards adopting a non-irrigation policy is needed if less frequent CBI is to be achieved.

The surgical outcome of prostate surgery (TURP and open prostatectomy) has definitely improved over the years. Improved laser surgical techniques have been introduced. With these improvements, especially in the area of surgical hemostasis, it is certainly time to reconsider the routine use of CBI, which has been an integral part of prostate surgery and might have been more relevant during the evolving stages of these surgeries. This is certainly important considering the human and financial cost as well as the potential complications of CBI, among other disadvantages. Having in place a policy aimed at avoiding the routine use of CBI is also needed to achieve less frequent CBI.

P- Reviewer: Donkov I, Naselli A S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Han M, Partin AW. Retrograde and suprapubic open prostatectomy. Campbell – Walsh Urology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier 2012; 2695-2703. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Blandy S, Lutman M. Hearing threshold levels and speech recognition in noise in 7-year-olds. Int J Audiol. 2005;44:435-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Edwards LE, Bucknall TE, Pittam MR, Richardson DR, Stanek J. Transurethral resection of the prostate and bladder neck incision: a review of 700 cases. Br J Urol. 1985;57:168-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Varkarakis I, Kyriakakis Z, Delis A, Protogerou V, Deliveliotis C. Long-term results of open transvesical prostatectomy from a contemporary series of patients. Urology. 2004;64:306-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Helfand B, Mouli S, Dedhia R, McVary KT. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia with open prostatectomy: results of a contemporary series. J Urol. 2006;176:2557-2561; discussion 2561. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Adam C, Hofstetter A, Deubner J, Zaak D, Weitkunat R, Seitz M, Schneede P. Retropubic transvesical prostatectomy for significant prostatic enlargement must remain a standard part of urology training. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004;38:472-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tubaro A, Carter S, Hind A, Vicentini C, Miano L. A prospective study of the safety and efficacy of suprapubic transvesical prostatectomy in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2001;166:172-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shaheen A, Quinlan D. Feasibility of open simple prostatectomy with early vascular control. BJU Int. 2004;93:349-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Hill AG, Njoroge P. Suprapubic transvesical prostatectomy in a rural Kenyan hospital. East Afr Med J. 2002;79:65-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Elkin EB, Weinstein MC, Winer EP, Kuntz KM, Schnitt SJ, Weeks JC. HER-2 testing and trastuzumab therapy for metastatic breast cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:854-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gilbert V, Gobbi M. Making sense of ... bladder irrigation. Nurs Times. 1989;85:40-42. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Scholtes S. Management of clot retention following urological surgery. Nurs Times. 2002;98:48-50. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Cutts B. Developing and implementing a new bladder irrigation chart. Nurs Stand. 2005;20:48-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ng C. Assessment and intervention knowledge of nurses in managing catheter patency in continuous bladder irrigation following TURP. Urol Nurs. 2001;21:97-98, 101-107, 110-111. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Adams AW. The range and practice of trans-urethral surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1951;9:279-307. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Byrne JE. Continuous bladder irrigation following prostatectomy. Med Bull St Louis Univ. 1952;4:77-79. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kinder CH. A simple irrigating catheter. Br J Urol. 1966;38:323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tinckler LF. Post-prostatectomy management--a new catheter system. Br J Urol. 1972;44:165-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Végh A, Magasi P. The importance of closed bladder irrigation in prostatectomy. Acta Chir Hung. 1988;29:137-141. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Miller A, Gillespie WA, Linton KB, Slade N, Mitchell JP. Postoperative infection in urology. Lancet. 1958;2:608-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Clark SS, Misurec R, Kumar H, Srinivasan V. Closed postprostatectomy irrigation-drainage system. I. Description and rationale. Urology. 1973;1:125-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Livne PM, Servadio C, Frischer Z, Nissenkorn I. Simple method of continuous bladder irrigation for prevention of postprostatectomy complications. Urology. 1982;19:314-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Caro DJ. A simpler method for continuous bladder irrigation. Urology. 1982;20:110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Okorie CO, Salia M, Liu P, Pisters LL. Modified suprapubic prostatectomy without irrigation is safe. Urology. 2010;75:701-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Koshiba K, Egawa S, Ohori M, Uchida T, Yokoyama E, Shoji K. Does transurethral resection of the prostate pose a risk to life? 22-year outcome. J Urol. 1995;153:1506-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ansari MZ, Costello AJ, Ackland MJ, Carson N, McDonald IG. In-hospital mortality after transurethral resection of the prostate in Victorian public hospitals. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:204-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Horninger W, Unterlechner H, Strasser H, Bartsch G. Transurethral prostatectomy: mortality and morbidity. Prostate. 1996;28:195-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Varkarakis J, Bartsch G, Horninger W. Long-term morbidity and mortality of transurethral prostatectomy: a 10-year follow-up. Prostate. 2004;58:248-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, Cockett AT, Peters PC. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. a cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. 1989. J Urol. 2002;167:999-1003; discussion 1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Reich O, Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Seitz M, Schlenker B, Hermanek P, Lack N, Stief CG. Morbidity, mortality and early outcome of transurethral resection of the prostate: a prospective multicenter evaluation of 10,654 patients. J Urol. 2008;180:246-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chander J, Vanitha V, Lal P, Ramteke VK. Transurethral resection of the prostate as catheter-free day-care surgery. BJU Int. 2003;92:422-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Rigatti P, Cestari A, Gilling P. The motion: large BPH should be treated by open surgery. Eur Urol. 2007;51:845-847; discussion 847-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Meier DE, Tarpley JL, Imediegwu OO, Olaolorun DA, Nkor SK, Amao EA, Hawkins TC, McConnell JD. The outcome of suprapubic prostatectomy: a contemporary series in the developing world. Urology. 1995;46:40-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Servadio C. Is open prostatectomy really obsolete? Urology. 1992;40:419-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Berger AP, Wirtenberger W, Bektic J, Steiner H, Spranger R, Bartsch G, Horninger W. Safer transurethral resection of the prostate: coagulating intermittent cutting reduces hemostatic complications. J Urol. 2004;171:289-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Okorie CO, Pisters LL. Effect of modified suprapubic prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia on postoperative hemoglobin levels. Can J Urol. 2010;17:5255-5258. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Lowthian P. Preventing clot retention after urological surgery. BJU Int. 2003;91:126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fuller E. Diseases of the genito-urinary system. New York: MacMillan 1900; . |

| 40. | Cabot F. Value of sight in suprapubic prostatectomy. Tr Am Urol. 1909;3:449. |

| 41. | Herman JR, Castro L. Suprapubic prostatectomy. Some early methods of hemostasis. Urology. 1973;1:612-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | McEachern AC. The evolution of safety in prostatectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1958;22:151-177. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Morson AC, Semple JE. A study of the craftsmanship of the Harris technique for prostatectomy. BJU. 1934;6:207-219. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Loughnane FM. Treatment of prostatic obstruction. Br Med J. 1937;16:144-145. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wilde S. See one, do one, modify one: prostate surgery in the 1930s. Med Hist. 2004;48:351-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Adams AW. A third ureter in prostatectomy. Br Med J. 1949;1:809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 47. | Attah CA. Effect of continuous irrigation with normal saline after prostatectomy. Int Urol Nephrol. 1993;25:461-467. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Schlegel JU, Jorgensen H, Mcfadden A, Scott WW. A physiological approach to bladder irrigation in gross hematuria. Trans Am Assoc Genitourin Surg. 1957;49:2-7. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Essenhigh DM, Eustace BR. The use of frusemide (Lasix) in the post-operative management of prostatectomy. Br J Urol. 1969;41:579-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Esho JO, Kuwong MP, Gbadamosi WB. Suprapubic prostatectomy without suprapubic tube and without bladder irrigation. Eur Urol. 1989;16:15-17. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Britton JP, Fletcher MS, Harrison NW, Royle MG. Irrigation or no irrigation after transurethral prostatectomy? Br J Urol. 1992;70:526-528. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Mobb GE, Farrar DJ. Is planned continuous irrigation indicated for haemorrhage following transurethral resection of the prostate? Br J Urol. 1993;71:707-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Malone PR, Davies JH, Standfield NJ, Bush RA, Gosling JV, Shearer RJ. Metabolic consequences of forced diuresis following prostatectomy. Br J Urol. 1986;58:406-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Jasiński Z, Wolski Z. A new technique of haemostasis following transvesical prostatectomy. Int Urol Nephrol. 1985;17:165-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Okorie CO, Pisters LL. Suprapubic prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia: aspects of evolution of hemostatic methods to present time. Prostatectomies: procedures, benefits and potential complications. New York: Nova publishers 2012; 31-47. |

| 56. | Mireku-Boateng AO, Jackson AG. Prostate fossa packing: a simple, quick and effective method of achieving hemostasis in suprapubic prostatectomy. Urol Int. 2005;74:180-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Bapat RD, Relekar RG, Pandit SR, Dandekar NP. Comparative study between modified Freyer’s prostatectomy, classical Freyer’s prostatectomy and Millin’s prostatectomy. J Postgrad Med. 1991;37:144-147. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Lower WE. Complete closure of the bladder following prostatectomy. JAMA. 1927;89:749-751. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Harris S. Prostatectomy with closure: Five years’ experience. BJS. 1934;21:434. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Silverton RJ. Sutural haemostasis in suprapubic prostatectomy. ANZ J Surg. 1934;3:276-283. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | De la pena A, Alcina E. Suprapubic prostatectomy: a new technique to prevent bleeding. J Urol. 1962;88:86-90. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Malament M. Maximal hemostasis in suprapubic prostatectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:1307-1312. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Cohen SP, Kopilnick MD, Robbins MA. Removable purse-string suture of the vesical neck during suprapubic prostectomy. J Urol. 1969;102:720-722. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Nicoll GA, Riffle GN, Andersen FO. Suprapubic prostatectomy. The removable purse string: a continuing comparative analysis of 300 consecutive cases. J Urol. 1978;120:702-704. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Denis R. Prostatectomy under depression. J Urol Nephrol (Paris). 1970;76:663-672. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Condie JD, Cutherell L, Mian A. Suprapubic prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia in rural Asia: 200 consecutive cases. Urology. 1999;54:1012-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Lezrek M, Ameur A, Renteria JM, El Alj HA, Beddouch A. Modified Denis technique: a simple solution for maximal hemostasis in suprapubic prostatectomy. Urology. 2003;61:951-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Nthumba PM, Bird PA. Suprapubic prostatectomy with and without continuous bladder irrigation in a community with limited resources. ECA J Surg. 2006;12:53-58. |

| 69. | Kavanagh LE, Jack GS, Lawrentschuk N. Prevention and management of TURP-related hemorrhage. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8:504-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Gilling PJ, Kennett K, Das AK, Thompson D, Fraundorfer MR. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) combined with transurethral tissue morcellation: an update on the early clinical experience. J Endourol. 1998;12:457-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Moody JA, Lingeman JE. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate with tissue morcellation: initial United States experience. J Endourol. 2000;14:219-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Kuntz RM. Current role of lasers in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Eur Urol. 2006;49:961-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Elzayat EA, Elhilali MM. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP): the endourologic alternative to open prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2006;49:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Stutzman RE. Urologic Surgery. 4th ed. Lippincott: Philadelphia 1991; 585-602. |

| 75. | Manley BJ, Gericke RK, Brockman JA, Robles J, Raup VT, Bhayani SB. The pitfalls of electronic health orders: development of an enhanced institutional protocol after a preventable patient death. Patient Saf Surg. 2014;8:39. [PubMed] |