INTRODUCTION

Approximately 500000 men in the United States undergo vasectomy every year. With a divorce rate of around 50%, up to 6% of men who have undergone vasectomy will elect to have the vasectomy reversed sometime in their lifetime[1,2]. Vasectomy reversal (VR) was described in the 1930’s and the use of the operative microscope for magnification to assist in the anastomosis was applied in the 1970’s and significantly improved patency rates[3-5].

ANATOMY

Understanding the anatomy of the vas deferens and the epididymis is paramount to successful outcomes with VR. The vas deferens, which is also known as the ductus deferens, extends from the distal end of the cauda of the epididymis. Its embryological origin is the mesonephric (wolffian) duct. It is a tubular structure, and the segment leaving the epididymis for the first two to three centimeters is known as the convoluted vas deferens, which is tortuous. The vas deferens measures between 30 and 35 cm in length from the cauda epididymis to the ejaculatory duct, where it terminates. The vas deferens travels behind the vessels in the spermatic cord, posteriorly. Depending on the segment, the lumen of the vas deferens ranges between 0.2 and 0.7 mm in diameter[6]. The deferential artery, a branch off of the superior vesical artery supplies the vas deferens[7]. The scrotal vas deferens’ venous drainage is via the deferential vein which drains into the pampiniform plexus. The venous drainage of the pelvic vas deferens is via the pelvic venous plexus. The vas deferens’ lymphatic drainage travels to the external and internal iliac nodes.

Sperm travel through the epididymis from the testis to reach the vas deferens. If the tightly coiled tubule known as the epididymis is uncoiled it would stretch the length of 12 to 15 feet long. The three regions of the epididymis are characterized as the caput (head), the corpus (body), and the cauda (tail). The caput epididymis is comprised of 8-12 ductuli efferentes from the testis. The most distal portion of the cauda epididymis is continuous with vas deferens. The arterial supply of the caput and corpus epididymis is from a branch of the testicular artery, which further divides to supply the superior and inferior epididymal branches[8]. Branches from the deferential artery provide vascular supply to the cauda epididymis. Venous drainage of the corpus and cauda epididymis are via the vena marginalis of Haberer, draining into the pampiniform plexus via the vena marginalis of the testis, or through cremasteric or deferential veins[8]. Lymphatic drainage of the caput and corpus epididymis is through channels that travel with the internal spermatic vein, draining to the preaortic nodes. Lymphatic channels from the cauda epididymis join those leaving the vas deferens to drain into the external iliac nodes.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION/PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Prior to undergoing VR, the level of spermatogenesis in the patient should be assessed. A history of fertility from prior to the vasectomy is typically considered sufficient. A full physical examination should be performed prior to VR with special attention to the genital examination. Testicular volumes and consistency should be assessed. Firm, normal volume testicles are indicators of good spermatogenesis whereas small or soft testes may indicate some spermatogenic deficiency. It is not uncommon for the epididymis to feel dilated in men who have undergone vasectomy. Epididymal induration may indicate the need for vasoepididymostomy (VE). When a large vasectomy defect or gap can be palpated, this should prompt counseling for a more extensive dissection to perform a tension free anastomosis. When a sperm granuloma is palpated at the testicular end of the vas deferens, this indicates leaking of sperm as a result of a pop-off valve like mechanism to decrease intra-epididymal pressures. Sperm granuloma are associated with better outcomes with VRs suggesting that the epididymis has protected itself by decreasing intraluminal pressures[9]. When physical examination reveals a very long vasectomy defect, a segment that has been removed, the surgeon should consider a non-standard incision approach[10]. As more men are being diagnosed and treated with testosterone replacement for hypogonadism, impacting the level of spermatogenesis, medical management must be considered prior to performing VR in these men. Testosterone replacement should be discontinued, testicular salvage therapy with clomiphene citrate or human chorionic gonadotropin should be implemented for approximately three months, and then VR can be performed with good outcomes[11].

The obstructive interval since the vasectomy has a significant impact on the type of VR required, vasovasostomy (VV) vs VE. This has been shown to affect patency rates in many studies and generally the longer the interval since vasectomy, the more challenging the candidate is considered to be for VR[12,13]. However, in the hands of a surgeon who is proficient in both VV and VE, VR should still be offered to men with longer obstructive intervals. In technically skilled hands, success rates remain high regardless of the type of VR performed in men with obstructive intervals over 10 years[14]. Multiple nomograms have been constructed to predict the type of VR required and patency rates. Factors evaluated to assess these outcomes include patient age, testicular volume, the presence of sperm granuloma, and obstructive interval[15,16]. There is a question of the accuracy of the nomograms and their utility with inconsistent data[17,18]. As it is not typically possible to predict preoperatively if VE will be required, VR should only be performed by surgeons skilled in both VV and VE[19,20].

Before a man undergoes VR, his female partner should undergo a fertility evaluation with counseling on female age and ovarian reserve on fertility potential[10].

PREOPERATIVE LABORATORY TESTING

Semen analysis with a centrifuged evaluation of the pellet may be performed prior to VR. Ten percent of these centrifuged pellets will reveal whole sperm suggesting good outcomes indicating that sperm will be found in the vas deferens at least unilaterally at the time of VR[21]. When the semen analysis reveals low semen volume, transrectal ultrasound should be performed to rule out the possibility of a concomitant ejaculatory duct obstruction.

When the physical examination indicates potential spermatogenic deficiency with findings such as small, soft testicles, a serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) should be obtained. An elevated FSH indicates spermatogenic failure, potentially poor outcome with VR, and requiring higher assisted reproduction use[22]. Serum antisperm antibody (ASA) testing is not recommended as a routine preoperative test prior to VR. Approximately 60% of men develop circulating ASAs after bilateral vasectomy[23]. Preoperative ASA testing is of unproven value, and the high postoperative conception rate after VR questions the impact of circulating ASAs on fecundability[24-31].

ANESTHESIA

VR may be performed with local, regional, or general anesthesia[10]. As meticulous microsurgical technique and tissue handling is mandated for superior outcomes, general anesthesia is the anesthesia of choice to minimize patient movement. Although VR can be performed with local anesthesia with sedation, this tends to result in more motion which makes a challenging operation more challenging. If a VE or a more difficult anastomosis is required, it may require lengthy operative times which can be difficulty on the patient under local anesthesia or sedation.

INCISION APPROACHES

The scrotal incision provides the most direct access to the vasectomy defect to isolate the ends of the vas deferens for anastomosis. In scenarios with high vasectomy defects or long vasectomy defects, the incision may be extended toward the external inguinal ring. The testis may be delivered in cases with a very low vasectomy defect or when a VE is deemed necessary. Mini-incision VR using no-scalpel vasectomy principles has been evaluated with comparable patency rates with less postoperative pain and faster functional recovery[32,33].

In men who have previously undergone varicocele repair or inguinal hernia repair, the surgical approach to VR will vary. If a man has undergone varicocele repair for orchialgia or for hypogonadism with a concomitant vasectomy, the VR should be approached through the prior subinguinal incision after confirming that the vasectomy was performed subinguinally by previous operative report. In men who have suspected vas deferens obstruction from previous inguinal herniorrhaphy, approaching the VR through the previous scar will lead to the site of the vas deferens obstruction.

PREPARING THE VAS DEFERENS

Once the vasectomy defect is isolated through the incision, the abdominal and testicular ends of the vasa may be isolated with the use of vessel loops. Care should be taken to not strip the vas deferens of the perivasal adventitia to maintain the microvasculature to the vas deferens. The abdominal and testicular ends of the vas deferens should be adequately mobilized, with its adventitia, to allow for a tension free anastomosis. The obstructed segment of the vas deferens at the vasectomy defect site may be excised. Care should be taken to preserve the artery during this maneuver. After the testicular and abdominal ends of the vas deferens are isolated, the testicular end of the vas deferens is sharply divided at an exact 90 degrees. The divided end should have the muscularis and the mucosa inspected under microsurgical magnification to confirm that there is a healthy surface to anastomose without fibrosis or scar. Fluid from the testicular lumen of the vas deferens is then applied to a glass slide and is diluted with a drop of saline and is examined under the light microscope. The quality of the fluid from the testicular end of the vas deferens and the microscopic findings dictate whether a VV or a VE should be performed. If microscopic examination of the vasal fluid reveals whole sperm with tails or when there is copious, clear fluid from the vas deferens but no sperm are found in the fluid, VV should be performed. If fluid is not present, a 24 gauge angiocatheter sheath is cannulated into the lumen of the testicular end of the vas deferens and barbatage is performed with 0.1 mL of saline which is then microscopically examined. If there is no significant vasal fluid or sperm identified after this maneuver, a VE should be performed. When the vasal fluid appears thick and toothpaste like in quality, sperm are typically not found on microscopic examination of the fluid, and VE is indicated. Data has shown that greater than 90% of VRs will be successful when sperm fragments (sperm heads and/or short tails) are found in the vasal fluid intraoperatively regardless of the fluid quality. This success rate surpasses the expected success rate with VE[34,35]. Sperm quality has been categorized in five grades to describe the findings in the vasal fluid. Grade 1 reveals mainly normal motile sperm, grade 2 mainly normal nonmotile sperm, grade 3 mainly sperm heads, grade 4 only sperm heads, and grade 5 no sperm[36,37].

The abdominal end of the vas deferens is divided in a similar manner. The lumen is gently cannulated with a 24 gauge angiocatheter sheath and saline is injected into the lumen to demonstrate patency. The ends of the testicular and abdominal vas deferens are then approximated with the use of a Microspike approximating clamp, or with carefully placed 6-0 prolene adventitial sutures to approximate the ends with the help of an assistant. A penrose drain covered metal ruler or tongue blade is then placed beneath the approximated ends to provide a template for the anastomosis. In the circumstance when saline is injected into the lumen of the abdominal end of the vas deferens and it reveals that there is not patency, this suggests another obstruction. A 2-0 polypropylene suture is carefully passed through the lumen of the abdominal vas deferens to encounter the site of distal obstruction. If this obstruction is isolated within 5 cm of the initial vasectomy site, the abdominal end of the vas deferens may be dissected to the obstruction site and excised to perform one anastomosis after further mobilization of both ends to allow for a tension free anastomosis. This may require extension of the incision. Performing multiple anastomoses on the vas deferens increases the risk for devascularization and failure.

ANASTOMOSIS PEARLS

A high level of microsurgical expertise is requires for optimal VR outcomes. Prognostic advantages are gained by strict surgical principles during the anastomosis. The luminal mucosa of the abdominal and testicular ends of the vas deferens should be approximated meticulously. The anastomosis should be water-tight as sperm are antigenic and will stimulate an inflammatory response which can lead to fibrosis and obstruction of the anastomosis if they leak at the anastomosis[38]. A tension free anastomosis is crucial for long term success. Mobilizing the abdominal and testicular ends of the vas deferens, and placing reinforcing, muscularis sutures to minimize tension on the anastomosis will improve long term patency rates. A minimal touch technique, with as little manipulation of the vasal ends for anastomosis is paramount to a successful outcome as is maintaining microvascular supply to the vas deferens by maintaining the vasal adventitia and not stripping the vas deferens.

MICROSURGICAL VASOVASOSTOMY

VV may be performed by a modified one-layer anastomosis, placing four to eight interrupted 9-0 nylon sutures through the full thickness of each end of the vas deferens lumens. Following the placement of these sutures, interrupted 9-0 nylon sutures are placed between these full thickness sutures in the muscular layer[39]. Some surgeons prefer a two-layer anastomosis, which is performed by placing five to eight 10-0 nylon interrupted sutures to approximate the inner mucosal edges of the ends of the vas deferens. Following the placement of these mucosal sutures, seven to ten outer muscular layer interrupted sutures of 9-0 nylon are placed[37]. Experienced microsurgeons compensate for the discrepancy in luminal diameters between the abdominal and testicular ends of the vas deferens during the anastomosis. Some place microdots with a microtip marking pen to preplan the suture placement prior to performing the anastomosis[40]. This technique utilizes interrupted 10-0 monofilament nylon sutures for mucosal approximation and interrupted 9-0 monofilament nylon sutures deep in the muscularis in between the already placed mucosal sutures. When VV is performed in the convoluted vas deferens, very meticulous technique is mandated for a successful outcome. Although this anastomosis is more technically demanding, patency rates are comparable to anastomosis in the straight portion of the vas deferens, when performed by skilled microsurgeons[41,42]. A useful maneuver in difficult circumstances is the trans-scrotal crossed VV. This technique allows for anastomosis of one testicular end of the vas deferens to the contralateral abdominal end of the vas deferens. This maneuver is used when there is unilateral inguinal vas deferens obstruction associated with an atrophic testis on the contralateral side, or obstruction of inguinal vas deferens and epididymal obstruction on the contralateral side[1,37,43,44]. Repeat VR is a valid option for men who failed an initial VR. The decision to perform a repeat VR should be based on the obstructive interval, the original VR, and the experience of the surgeon[45,46].

When VVs are performed after sperm is found in the vasal fluid of at least one side, postoperative patency is demonstrated by the presence of sperm in the ejaculate in up to 99.5% of men[40]. One-layer VV and two-layer VV have been shown to have similar patency rates[47,48]. Pregnancy rates within two years of VR of 52% have been achieved and up to 63% with exclusion of female factor and when based on female partner age and the time since vasectomy[9,49-53]. Postoperative semen quality and female factors and age of the female partner determine the rates of spontaneous conception in couples after VR[47,54].

VASOEPIDIDYMOSTOMY

VE is a highly technically demanding operation, must be performed under magnification, and should only be performed by microsurgeons with appropriate training and experience in this operation who perform it frequently. When the decision to perform a VE is made, anastomoses are less technically challenging and more likely to succeed in the distal regions of the epididymis, as the epididymal wall thickens more distally with more smooth muscle cells. As the corpus and cauda of the epididymis is a single microscopic tubule, obstruction at any point will lead to a complete blockage of sperm from entering the vas deferens. The use of the operative microscope significantly improves VE patency rates[55,56]. Multiple techniques have been employed to perform VE. VE may be performed by end-to end or end-to side anastomosis[19,20]. The end-to end anastomosis has fallen out of favor for the most part. The end-to-side VE is performed by identifying the presence of markedly dilated epididymal tubules and approximating the muscularis and adventitia of the vas deferens to a specific opening in the tunica of the epididymis. This is a relatively bloodless and atraumatic technique[20,56-60]. The testis is delivered through a scrotal incision. The vas deferens is isolated with a vessel loop at the junction of the straight and convoluted vas deferens. The vas deferens is transected sharply and is prepared as previously described above. The tuinca vaginalis is incised and the epididymis is inspected under magnification. The anastomotic site on the epididymis is identified where tubules are dilated, proximal to the suspected obstruction. A 3-4 mm incision is made in the tunica with microscissors overlying the dilated tubules. The epididymal tubules are gently dissected and exposed. The end of a 10-0 nylon needle is used to puncture the selected epididymal tubule and the fluid is examined microscopically to identify sperm. The vas deferens is secured to the epididymal tunica with 3-4 interrupted 6-0 polypropylene sutures with positioning allowing the vasal lumen to reach the opening of the epididymal tunica without tension. Under 25-32 magnification, interrupted 10-0 monofilament nylon sutures double armed with fishhook tapered needles are used to approximate the posterior mucosal edge of the epididymal tubule the posterior vasal mucosa. Two to four additional 10-0 sutures are used for the anterior mucosal anastomosis. Six to ten additional interrupted 9-0 sutures are used to approximate the outer muscularis and adventitia of the vas deferens to the incised edge of the epididymal tuinca. The testis and epididymis is carefully placed back in the tuinca vaginalis and the scrotum is closed in layers.

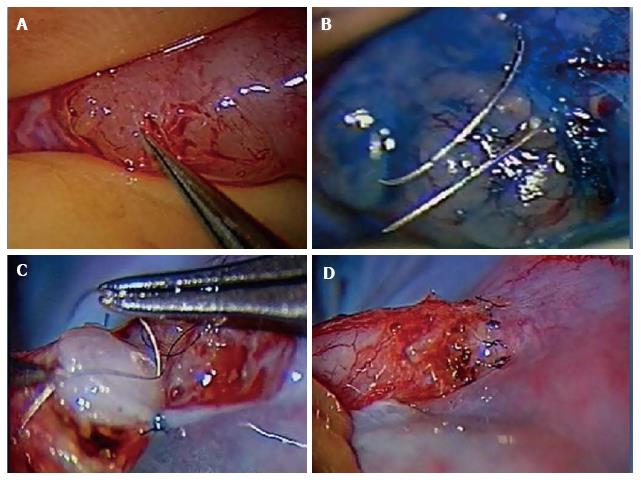

The authors preferred technique for VE is the 2 stitch intussusceptions technique. Two parallel needles of double armed 10-0 nylon sutures are placed in the dilated epididymal tubule longitudinally without pulling them through to avoid leakage of tubular fluid and collapse of the dilated tubule. A microknife is used to make an opening longitudinally in the tubule between the parallel placed sutures. The fluid is examined microscopically for the presence of sperm. The needles are then passed inside out the vas deferens mucosa to perform the intussuscepted anastomosis[56,60-62]. The muscularis and adventitia are anchored the epididymal tunica as described above (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Microsurgical vasoepididymostomy.

A: Dissection of dilated epididymal tubules; B: Placement of needles for the 2 stitch technique; C: Placement of mucosal vas deferens luminal stitch; D: Completed vasoepididymostomy anastomosis.

In the hands of experienced, skilled microsurgeons, VE patency rates are reported between 50% and 85%[61,63]. Men who underwent the classic end-to side or older less commonly performed end-to-end anastomosis will have respective patency and pregnancy rates of approximately 70% and 43%[55,64]. The intussuscepted techniques patency rates range between 70% and 90%[56,60,65].

ROBOT ASSISTED VASECTOMY REVERSAL

VR has traditional been performed with magnification through the use of the operative microscope. Recently, da Vinci robot assistance has been applied to VR. Robotic assistance was first utilized on ex vivo human vas deferens to perform VV with the findings of elimination of physiological tremor and comparable patency rates suggesting that the robot may be used as an alternative to the operative microscope[66]. Robot assisted VV and VE were then performed in the rat model. The findings were improved stability and motion reduction during suturing of the anastomosis[67]. A multilayered robot assisted VV was performed in an in vivo rabbit model with comparable patency rates, reinforcing the suggested role of robotics in microsurgery[68]. Robot assisted VR was performed in humans and resulted in shorter operative times and higher sperm counts in early postoperative semen analyses when compared to microsurgical VR[69]. A validating human study on robot assisted VR compared to microsurgical VR demonstrated comparable patency rates, operative times, and early postoperative sperm concentrations and total motile counts. Although the mean anastomosis time in the robotic group was statistically significantly longer in the early robotic experience than the microsurgical group, this equated to a ten minute longer mean anastomosis time clinically[70]. The suggested advantages of the use of the operative robot for such microsurgery include: elimination of physiologic tremor, improved stability, surgeon ergonomics/decreased surgeon fatigue, scalability of motion, three-dimensional high-definition visualization, the ability for the surgeon to manipulate three surgical instruments and the camera simultaneously, not requiring a specialty skilled microsurgical assistant, and the potential of improving operative times[70]. This early data shows promise, however; large-scale prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the broader adoption of robot assistance for VR.

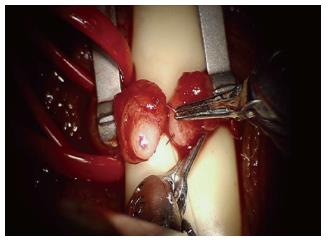

The robotic platform has provided advantages for more challenging scenarios such as use for intra-abdominal VR following laparoscopic vasectomy or in men with vasal obstruction due to inguinal hernia repair with mesh (Figure 2)[71,72].

Figure 2 Placement of the full thickness transluminal stitch for a modified one-layer anastomosis with robot assistance.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

VR is performed as an outpatient surgery. Once the patient has recovered from anesthesia, he may ambulate. Immediately following VR, the patient should be placed in a tight fitting scrotal supporter with fluff gauze. An ice pack to the scrotum is recommended for the first one to two days postoperatively. Postoperative antibiotics are not indicated. Analgesics may be given, but are not always needed. Most men return to work three days postoperatively as long as they do not partake in heavy or physical activity at work. No intercourse, ejaculation, exercise, or strenuous activity is allowed for three weeks after surgery. Semen analysis is obtained at 6 wk, 3 mo, and 6 mo postoperatively and every 6 mo thereafter until the couple achieves a pregnancy or further assistance is required. If azoospermia persists at 6 mo postoperatively, this indicates a failure in the procedure, requiring a discussion of options including a repeat attempt at reconstruction vs sperm retrieval to be used with in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

COMPLICATIONS

Hematoma and infection are rare complications of VR. Damage to the deferential artery adjacent to the vas deferens is a potential intraoperative complication. Although there are two other arterial supplies to the testicle, the gonadal and cremasteric arteries, great care should be taken to preserve the deferential artery. Late stricture and obstruction are represented by progressive loss of sperm motility followed by decreasing sperm counts and eventually azoospermia in some men. Late obstruction has been reported to range between 5% and 12% at 18 mo following VR[65,73]. As a precaution, it is recommended that men cryopreserve sperm once motile sperm are identified in the ejaculate after VR.

CONCLUSION

VR is a very effective method of reestablishing fertility for men who have undergone vasectomy with extremely high success rates when performed by skilled, highly trained surgeons. Surgeons must not only be technically proficient with acceptable success rates with both VV and VE in order to provide this service; but they must have an in depth understanding in the evaluation, treatments, and post-operative management of these men. Different technical variations have developed over the years and continue to advance.

P- Reviewer: Creta M, Peitsidis P, Patanè S S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ