Published online Jul 24, 2014. doi: 10.5410/wjcu.v3.i2.96

Revised: May 14, 2014

Accepted: June 14, 2014

Published online: July 24, 2014

Processing time: 127 Days and 2.7 Hours

As a combined electrophysiological system for evaluating the lower urinary tract (LUT), comprehensive urodynamics (UDS) aims at duplicating patient’s micturition process, either normal or abnormal, and further seeking for possible causative origin, either neurogenic or non-neurogenic, in order to guide treatment. Through thorough analysis, some so-called cut-off values, for example, bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) degree or dyssynergic degree between the detrusor and sphincter, could be gained; however, in most cases, their qualitative description, such as stress urinary incontinence, idiopathic detrusor underactivity (DUA), detrusor overactivity (IDO), low compliance, and idiopathic sphincter overactivity (ISO), is more preferable and important. In aged neurologically intact male patients with symptoms of the LUT (LUTS) including benign prostatic hyperplasia, a combined UDS system, which coupled BOO with compliance, was constructed. The patients may be categorized into one of the seven subgroups, including equivocal or mild BOO with sphincter synergia with or without IDO (pattern A), equivocal or mild BOO with ISO (B), classic BOO with sphincter synergia (C) or ISO (D), BOO with only low compliance (E), BOO with both DUA and low compliance (F), and potential BOO with DUA (G). This new system can be used to optimize diagnosis and treatment according to a derived guideline diagram.

Core tip: Scant progress during the last 2 decades and poor prognostic value of urodynamics (UDS) for benign prostatic hyperplasia interventional therapy may come from some technological problems, here we mean the underestimation of the role of electromyogram and some shortcomings of the UDS technology. Based on individualized UDS evaluation of more than 9000 cases, some so-called cut-off values, for example, degrees of bladder outlet obstruction and dyssynergia between the detrusor and sphincter, could be gained; however, in most cases, their qualitative description, such as stress urinary incontinence, idiopathic detrusor underactivity, detrusor overactivity, low compliance, and idiopathic sphincter overactivity, is more preferable and important.

- Citation: Qu CY, Xu DF. Comprehensive urodynamics: Being devoted to clinical urologic practice. World J Clin Urol 2014; 3(2): 96-112

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2816/full/v3/i2/96.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5410/wjcu.v3.i2.96

Comprehensive urodynamics (UDS) performed for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) female patients has been challenged by two recent published papers[1,2]. Does it take no good for SUI or patients with symptoms of the lower urinary tract (LUTS)? This was just the same as UDS for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) patients in the late last century[3,4]. However, discerning experts indicated that the studies may have some common conceptual flaws, and there is a need to do more[5]. The authors therefore sighed, “scant progress has been made in the UDS recently[5].”

The NICE guidelines for the management of SUI[6] state that “the use of multichannel cystometry is not routinely recommended before surgery in women with a clearly defined clinical diagnosis of pure SUI”. However, in a study of 6276 women with urinary incontinence, Agur et al[7] found that only 324 (5.2%) women had pure SUI. Although the symptomatic assessment had a specificity of 98%, its sensitivity was too low (11.4%).

As a combined electrophysiological system for evaluating the lower urinary tract (LUT), comprehensive UDS aims at duplicating patient’s micturition process, either normal or abnormal, and further seeking for possible causative origin, either neurogenic or non-neurogenic, in order to guide treatment. Through thorough analysis, some so-called cut-off values, for example, bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) degree or dyssynergic degree between the detrusor and sphincter (TL value), could be gained; however, in most cases, their qualitative description, such as SUI, idiopathic detrusor underactivity (DUA), detrusor overactivity (IDO), low compliance, and idiopathic sphincter overactivity (ISO), is more preferable and important[8].

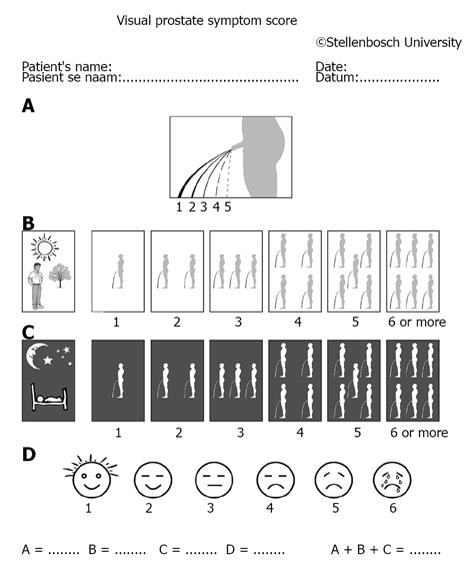

Whether a measuring system is inferior or non-inferior (i.e., superior) is confirmed or based on large-sample population studies on one hand; however, decision on given patients should be made individually on the other hand. The important recording of electromyogram (EMG) was often absent in large sample trials and whether the patients had such finding as ISO or DUA was scant too[1,2,7]. Symptomatic analysis is usually preferable as compared with invasive measures, however, there are many uncertainties and variable factors. The most often used symptom score system IPSS (International Prostatic Score System) has been challenged by newly launched system VPSS (Visual Prostatic Score System) (Figure 1). A combination of VPSS > 8 and Qmax < 15 mL/s was used to select invasive evaluation during follow-up in men with urethral strictures[9]. Patients with bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis (BPS/IC) and OAB patients had significant differences in their 3-d voiding diary records. Patients with BPS/IC had higher voiding frequencies and smaller maximal voided volume compared with OAB patients[10].

There are some differences between symptomatic and laboratory findings in clinical practice. Most clinical studies have relied on questionnaires as to the prevalence, symptoms, and treatment usage; however, the surveys must be interpreted with caution. So we should not let this prevent us from obtaining information via the use of laboratory tests including UDS combined with sphincter EMG. Furthermore, the symptom location is usually very factitious and clinical tests are necessary. For example, the pain caused by BPS/IC was often obscure. The study on BPS/IC prevalence could not find a single symptom-based definition of BPS/IC with ideal sensitivity and specificity to distinguish patients with BPS/IC from those with OAB, vulvodynia, or endometriosis[11]. The symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, do overlap with those of BPS/IC[11]. The patients and doctors make every effort to reveal a sufficient description of the symptoms to prompt a rational diagnosis. The similarity of symptoms might have nosologic implications. If we want to locate the origin of symptoms and to validate the nature of the disease, necessary examinations, including UDS and EMG, had to be carried out[11].

The targets of invasive UDS test are: pursuing after completeness instead of simplicity[12] and selecting complete or appropriate UDS if feasible; clearly defining UDS entities and seeking cutoff values in order to subcategorize possible pathological process, although descriptive recording is often more preferable; and developing evidence-based or knowledge-based strategies based on UDS findings[13].

New studies should be performed using high quality UDS with possible cutoff parameters, and show treatment methods linked to UDS findings. This paper broadly reviews the fundamental concepts behind the technique, application, and interpretation of UDS testing and how they are applicable to general urologists in office settings. Some of the discussion is based on the authors’ experience and the existing literature in the field.

The field of UDS has evolved significantly since its conceptual inception in the early twentieth century. UDS is a general term for a collection of techniques performed in an attempt to qualify and quantify the LUT activity during filling or storage, and emptying phases. Conceptually, normal, efficient bladder filling and storage require five components: (1) bladder compliance (distensibility); (2) bladder stability; (3) competence of ureterovesical junctions (i.e., non-refluxing ureters); (4) closed vesical outlet at rest and during times of increased intra-abdominal pressure; and (5) appropriate bladder sensations. Bladder emptying requires: (1) constant detrusor contraction; (2) simultaneous relaxing of the smooth and striated sphincter; and (3) non-obstructed bladder outlet. Any abnormality of filling and storage or of emptying, regardless of causative pathophysiology, must result from a problem related to one of these factors. UDS studies can assist in categorizing and quantifying these problems[13]. Comprehensive UDS studies are a combination of noninvasive measures, such as initial uroflowmetry, and invasive measures, such as cystometrogram (CMG), pressure-flow study (PFS) with EMG, and urethral pressure profilometry (UPP). With the evolution of the personal computer, much development has been achieved in the field of UDS. The advent of smaller, less cumbersome, and less expensive machines has expanded the availability of complex UDS, including videourodynamics (VUDS) and ambulatory UDS (AUDS), to more practicing urologists[13,14].

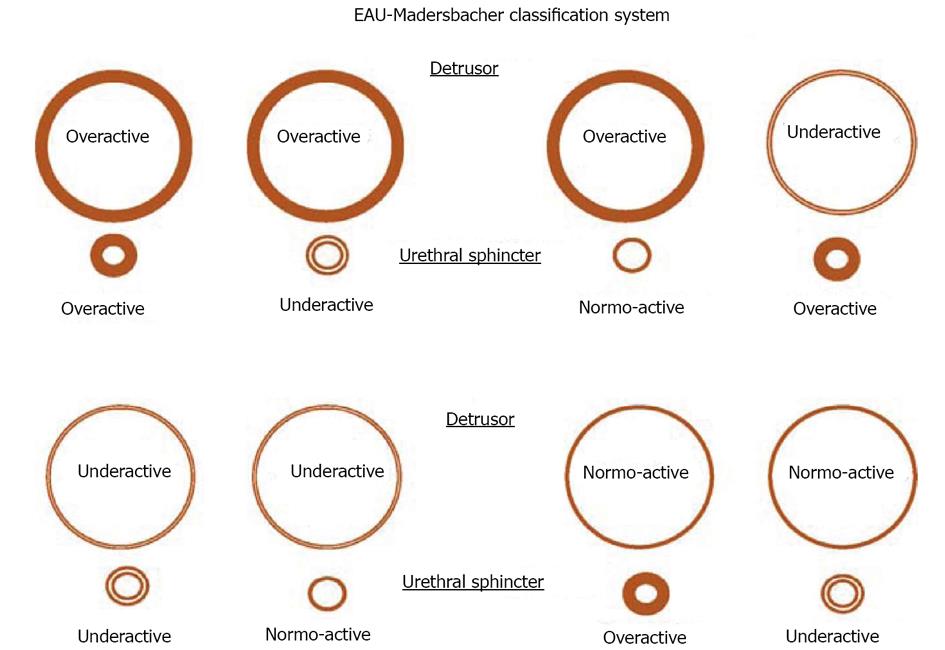

PFS has been viewed as the urologic equivalent of cardiac catheterization[3]. These figurative words are right in some extent. There are still some differences between the two techniques: first of all, cardiac catheterization only needs patient’s quiet recumbency, and not complex cooperation. UDS needs the patient’s full cooperation to fulfill the process of storage and emptying. We would rather like to analog a patient as an actor or actress, and an urodynamicist as a director whose duty is to guide the patient to show his/her micturition process as actually as possible. Through their performance (complete storage and voiding behaviour, not only storage) by not only the leading role (detrusor), but also the co-star (sphincter), we could know whether the detrusor relaxes and the sphincter contracts during storage phase, and the detrusor contracts and the sphincter relaxes during empty phase or not, or vice versa. The guideline of normal detrusor and sphincter is “stretch out whenever necessary, and do not stretch out whenever unnecessary”. Breach of the principle leads to dysfunction of the LUT: overactivity means “stretching out whenever unnecessary”, and underactivity means “unable to stretch out whenever necessary”. These demands and disability of the patients with potential lesions involving neurogenic system were exhibited in neurogenic LUTD guidelines (Madersbacher classification system)[15], in which the interrelationship or mutuality of the detrusor and sphincter was evaluated (Figure 2). In male patients, sphincter underactivity may exist clinically, however, its standard is not practical and data about its prevalence is scant. Furthermore in non-neurogenic LUTD, dysfunction of the detrusor or sphincter was presented separately, not integratedly as in neurogenic LUTD (NLUTD)[16] (Table 1).

| Failure to restore |

| Because of bladder |

| Detrusor hyperactivity |

| Involuntary contractions |

| Neurogenic diseases, injury, or degeneration |

| Bladder outlet obstruction |

| Inflammation |

| Idiopathic |

| Decreased compliance |

| Neurogenic disease |

| Fibrosis |

| Idiopathic |

| Detrusor hypersensitivity |

| Inflammatory |

| Infectious |

| Neurogenic |

| Psycologic |

| Idiopathic |

| Because of outlet |

| Stress incontinence (hypermobility related) |

| Nonfunctional bladder neck-proximal urethra (intrinsic sphincter dysfunction) |

| Failure to empty |

| Because of bladder |

| Neurogenic |

| Myogenic |

| Psycogenic |

| Idiopathic |

| Because of outlet |

| Anatomic |

| Prostatic obstruction |

| Bladder neck contracture |

| Urethral stricture |

| Urethral compression |

| Functional |

| Smooth sphincter dyssynergia |

| Striated sphincter dyssynergia |

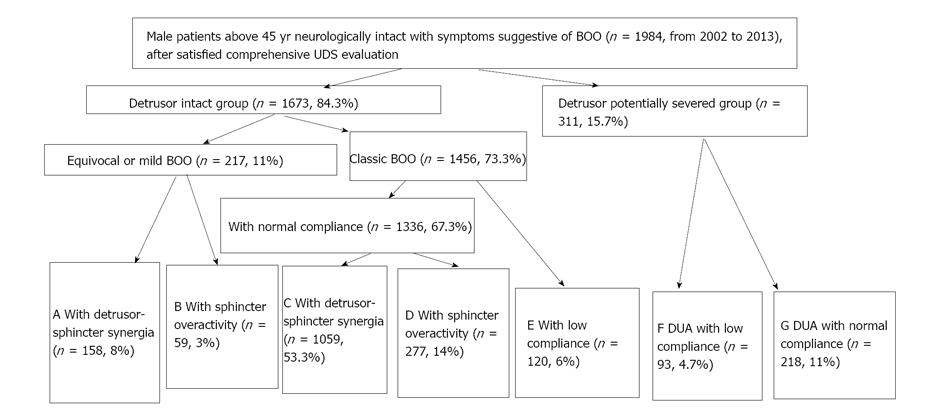

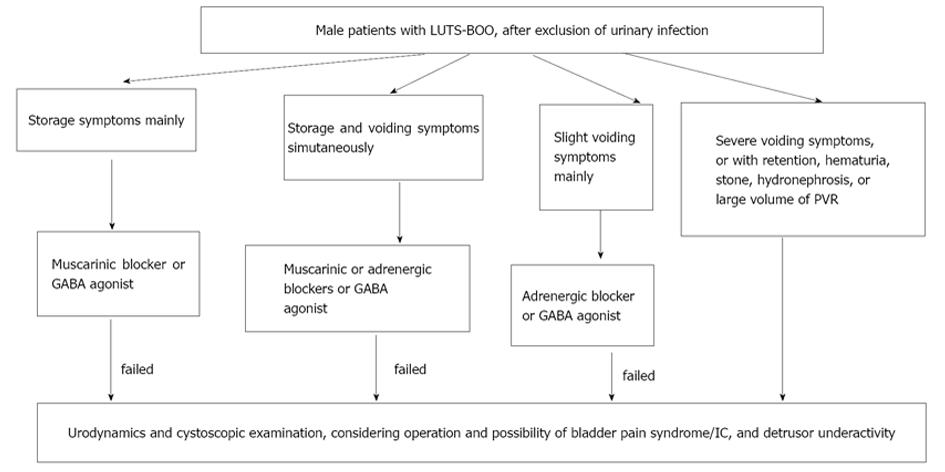

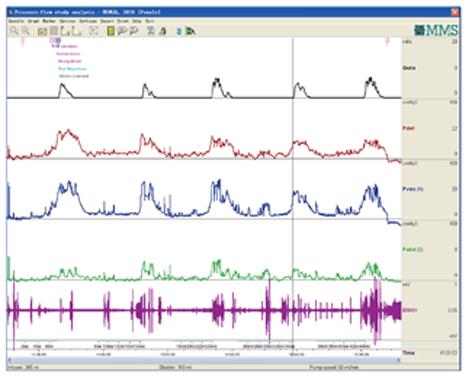

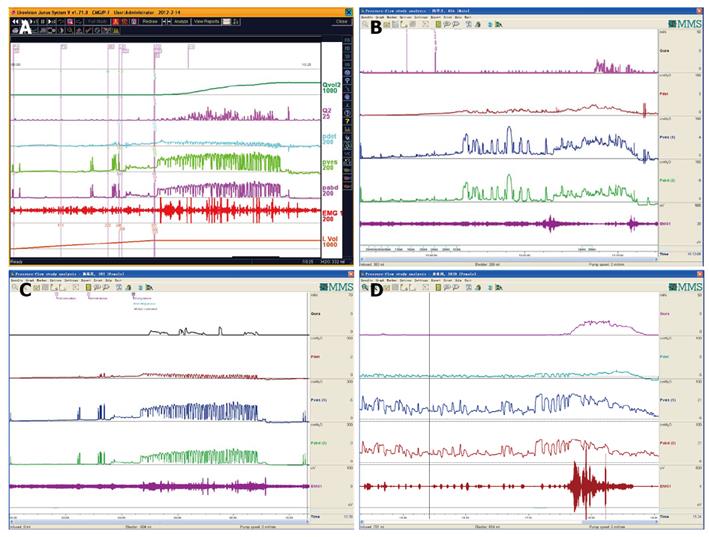

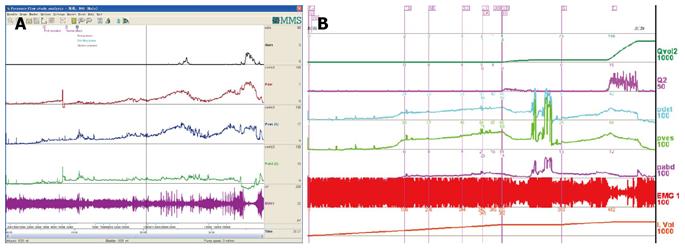

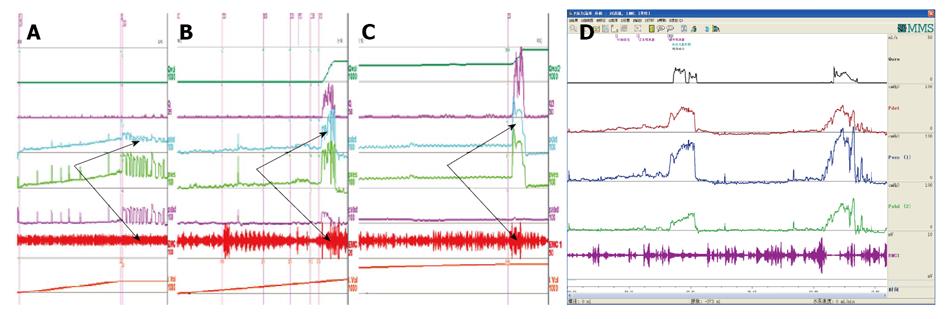

We think in urology practice, dysfunction of the detrusor, sphincter, detrusor compliance, incontinence state, and BOO had better been parceled on the basis of individualization. We have attempted this work and published a paper[17], which aimed at developing a UDS pattern system for aged male patients who complained of non-neurogenic LUTS to create a reference guideline for their diagnosis and treatment by a retrospective analysis. A retrospective analysis of UDS data was carried out in 1984 male patients neurologically intact with symptoms suggestive of BOO aged older than 45 years (2002-2013). On the basis of their UDS characteristic findings, the patients were classified into 1 of 7 subgroups: equivocal or mild BOO with sphincter synergia with or without IDO (pattern A); equivocal or mild BOO with ISO (B); classic BOO with sphincter synergia (C) or ISO (D); BOO with only detrusor low compliance (E); BOO with both DUA and low compliance (F); and equivocal BOO with DUA (G). The feasibility and rationality of this system were confirmed. The distribution of 7 patterns (pattern, case number, %) was A 158, 8%; B 59, 3%; C 1059, 53.3%; D 277, 14%; E 120, 6%; F 93, 4.7%; and G 218, 11% (Figures 3 and 4). The Abram-Griffiths (A-G) numbers (PdetQmax-2Qmax) in patterns C, D and E were 103.1-141.4, higher than those in other patterns (P < 0.001), and functional pressure lengths (FPL) in patterns C and D were 7.0-7.2 cm, longer than those in other patterns (P < 0.001). At last, a practical UDS pattern system for aged male patients with LUTS suggestive of BOO was constructed, which helps us to optimize the diagnosis and treatment[17]. For those with patterns A and B, medicinal therapy with 5a reductase inhibitor, antimuscarinics, or baclofen was administered first, whereas surgical intervention was reserved as an alternative option if medicinal therapy failed or their symptoms of BOO aggravated later. Those with patterns C, D and especially with E received transurethral resection of the prostate, and those with patterns F and G received 4-6 wk indwelled catheterization and administration of pyridostigmine bromide, baclofen, and decoction of Chinese medicinal herbs in an attempt to promote recovery of the detrusor contraction (Figure 5). These affordable principles may enrich the therapy of male LUTS using medical and/or conservative methods[18]. An integrated UDS pattern trial of 2195 female LUTS patients had been conducted, which revealed different results from those obtained from male patients[20]. At first they were divided into SUI and non-SUI groups and low compliance was seldom seen in neurologically intact women and was omitted in the calculation. At last, the distribution of UDS patterns were NA (normal detrusor-sphincter function) 50.2% (1101 cases), IDO 18.3% (401 cases), ISO 13% (286 cases), IDO + ISO 7.6% (167 cases), and DUA 10.9% (240 cases). We think the applicable principles from male population suit to female population too[19].

EMG technology: Scant progress during the last 2 decades and poor prognostic value of UDS for BPH interventional therapy may come from some technological problems, here we mean the underestimation of the role of EMG and some shortcomings of the UDS technology. Surface or patch electrode was routinely used as the standard option during UDS and the abnormal EMG findings were usually blamed as artifacts[20]. There are surface electrode, concentric needle electrode (CNE), and needle-guided wire electrode (simple as wire electrode[8]) available in practice. CNE was superior over surface electrode[21]. From our experience, needle guided wire electrodes were superior to CNE[22]. From our experience of about 9000 patients from 2002 to 2014, nearly 70%-80% so-called “artifacts” or bad recordings of EMG came from technical errors and we can record detrusor sphincter synergia or dyssynergia well using Solar from MMS (Netherlands), or Andromeda from Germany, as Janus from Life-tech (United States). We used the anal sphincter instead of the urethral sphincter to obtain EMG information[23]. Although some authors stated that anal and urethral sphincter EMG had the same significance[24], we believe that finding abnormal EMG signs in neurogenic diseases is more important than interpreting potential differences between the two routes. Anal external sphincter has a bigger mass than urethral external sphincter, less potential of pain and bleeding when needle is inserted into them, and less artifact possibility. In our laboratory CNE, anal plug electrodes and urethral catheter containing concentric electrodes are abandoned because of lower accuracy. CNE has also two poles indeed: one in the core of the needle, the other in the outer coating of the needle.

Patient position during UDS procedures: The position should be as natural and physiologic as possible, and we prefer sitting for female patients, sitting or standing for male patients. For patients whose sitting or standing position is unfeasible, they may take the supine position on the UDS bed with the barrow together. If they could pass urine during PFS stage, the simultaneous imitation of urinary flow into the commode is conducted. For patients whose original position does not fit PFS, their position should be changed, i.e., from sitting to squatting or standing. After position change, the same magnitude of increase of abdominal and bladder pressure produces, and their detrusor pressure is stable and no adjustment is required. The abdominal catheter may be ejected out by excessive abdominal strain during emptying phase in patients with DUA. If this happens, the abdominal pressure (Pabd) no longer works as a reference value for detrusor pressure, which means the difference between the vesical pressure (Pves) and Pabd (Pdet = Pves-Pabd). Measures should be taken to adjust Pabd, usually zeroing it.

UDS catheter and infusion medium selection: Catheters of UDS include urethral catheter and anal catheter. The former, either one, double or three-lumen, is usually afforded by appropriate companies and is disposable. Now an 8F double-lumen transurethral catheter (Xubu Medical Appliance Company, Dantu District, Jiangsu Province, China) is used for Pves recording and infusion of normal saline in our institution. The Pabd is recorded using a 12F transrectal balloon catheter (Cook Urological Incorporated, IN)[17]. The balloon covered with an envelope is lubricated and inserted into the anus and then semi-filled with saline, which assures satisfactory recording of the pressure. As far as the infusion medium is concerned, saline and air are used at the early stage, and normal saline is more suitable than air because of its physiologic property and ability to suit PFS[25].

UDS manufacturers: There are many UDS manufacturers or companies around the world, including MMS (Netherland), Life-Tech (United States), Andromeda (Germany), Leborie (Canada), Wearnes (Chengdu, China), etc. The design and performance are nearly the same. Our institution has the experience with products from all these companies.

Early diagnosis and treatment are essential for patients with LUTS[15]. UDS findings, either as cut-off values or descriptive conclusions, may indicate possible lesions that later emerge, give preoperational forecasting of surgery for BOO, evaluate possible organic lesions other than functional origin, and main dysfunction sites, either the bladder or urethra or both.

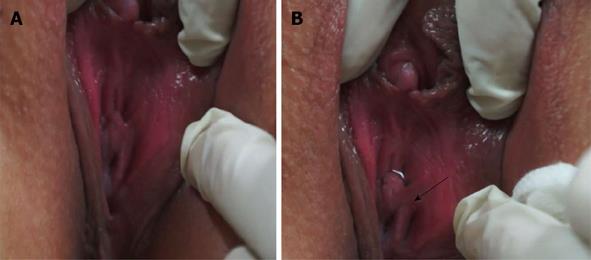

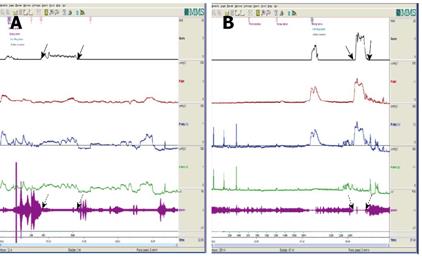

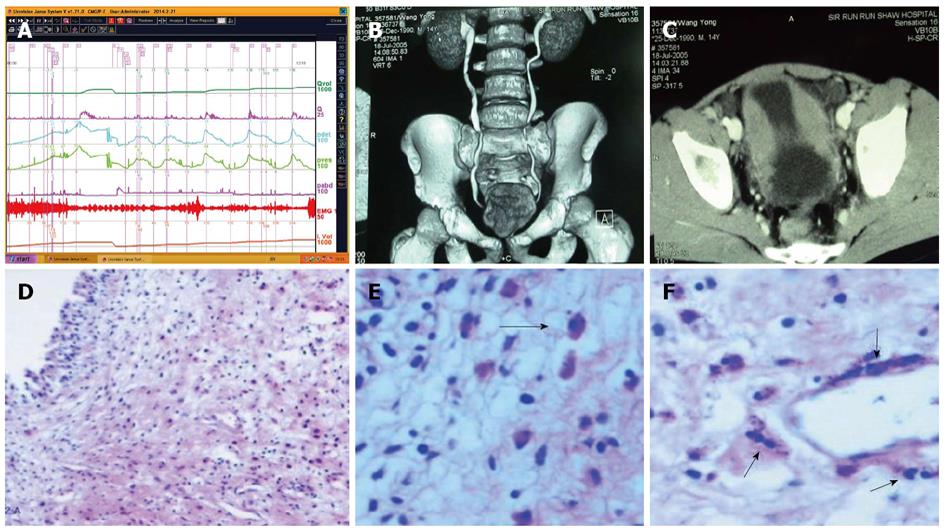

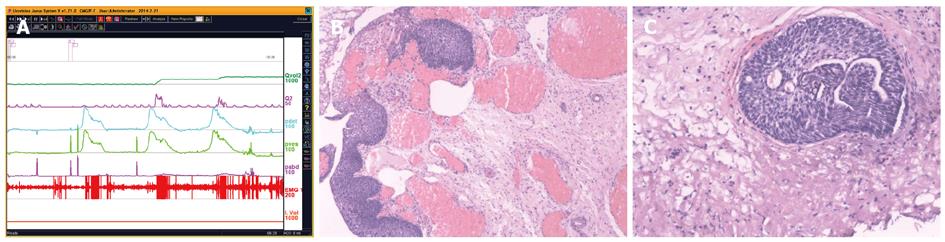

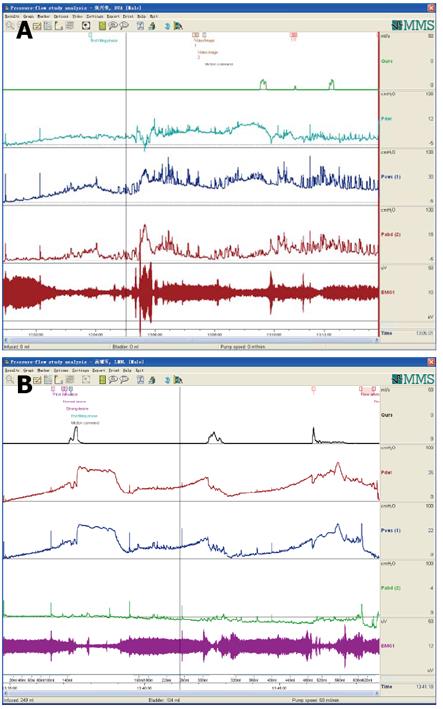

Uroflowmetry curve: Uroflowmetry usually indicates whether the bladder outlet is obstructed or the detrusor is unable to contract. Here we report a special case with sustained urinary incontinence after birth and her low and smooth “uroflowmetry” curve represented infused fluid leakage. This was a 24-year-old unmarried Chinese female referred for evaluation of congenital urinary incontinence. A transperitoneal anastomosis of both ureters to the bladder was carried out based on an assumption of ectopic ureteral orifices in the bladder neck and failed to cure her incontinence five years ago. She was neurologically normal and denied the presence of any other symptoms. She had good pelvic support and normal external genitals including the hymen. No abnormal neurologic signs were found. Ultrasonic test revealed that her kidneys, uterus, ovary and bladder were all normal. However, transrectal ultrasonography revealed that circular low echogenic zone of the peripheral region of the mid urethra, which represents the urethral striated sphincter[26], was absent. An intravenous urogram showed normal kidneys, ureters and bladder, too. There was no visible endoscopic evidence of vesicourethral lesions except for urinary leakage. When an inspection of her perineum in lithotomy position was performed, a rhythmic leakage of urine was observed, which was much like the way that urine jets ejected from ureteral orifices into the bladder being observed during cystoscopy both in rhythm and quantity (Figure 6). Each time she could only pass less than 30 mL with a maximum flow rate of 5 mL/s. UDS revealed that her bladder had no storage function at all, and we observed that more than 400 mL liquid was expelled after 360 mL normal saline had been infused at a rate of 50 mL/min. The flow or leakage rate was 1 mL/s, i.e., 60 mL/min. During storage phase with virtually constant leakage, the detrusor had no contraction (Figure 7A), and as infusion ended, the anal sphincter EMG recovered to normal storage state (Figure 7A), which meant normal anal sphincter function, but not urethral sphincter function. Congenital urethral sphincter agenesis (much severe than intrinsic sphincter deficiency, ISD) was a supposed diagnosis. In order to reconstruct a functional urethral sphincter, urethral external sphincteroplasty using an autologous fascial sling which was obtained from her left fascia lata, was performed successfully. Double rolls of the sling around the urethra were formed, one fixed to the public union and the other to the sheath of the rectus. The patient achieved full continence thereafter and could pass urine ideally in an interval of 30 min to 2 h two weeks after the operation. At the follow-up 4 months after the procedure, she could pass urine with more than 250 mL in an interval of 2-3 h, and UDS showed that her detrusor could contract normally with a Qmax of 23 mL/s and her anal sphincter worked as preoperational status (Figure 7B).

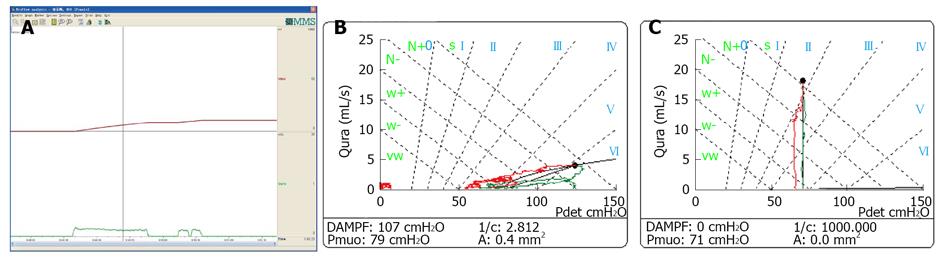

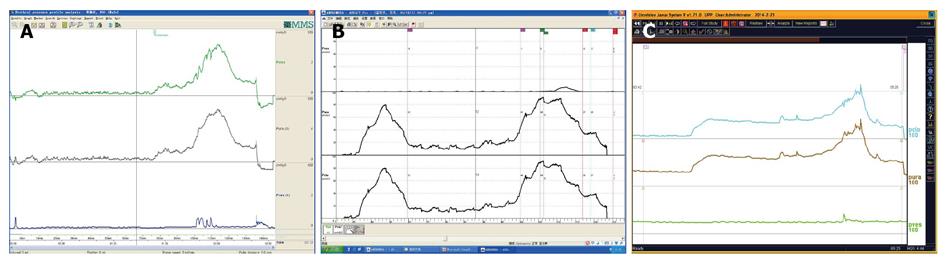

Low-smooth uroflowmetry curve is also associated with constrictive BOO, for example, urethral stricture (Figure 8A). This type of BOO is different from compressive BOO, such as that due to BPH[27]. Constrictive BOO produces a decreased slope of the passive urethral resistance relation (PURR) curve and a normal minimal opening pressure (Pmuo) (Figure 8B), whereas compressive BOO produces a steep slope of the PURR curve and a higher Pmuo[27] (Figure 8C). In typical cases, low-smooth uroflowmetry curve and characteristic finding of constrictive BOO aid the diagnosis of urethral stricture, especially in female patients with a UTI history.

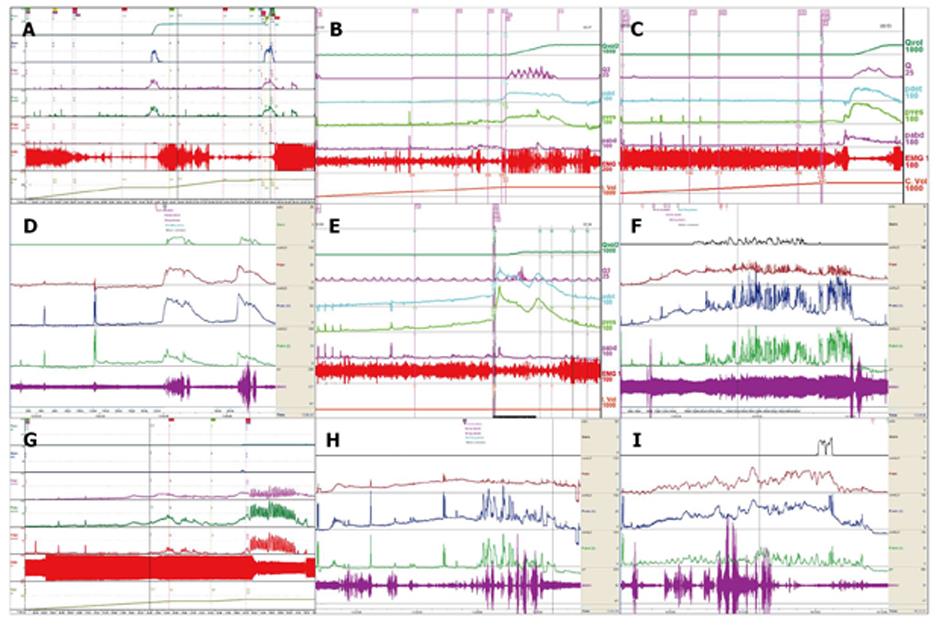

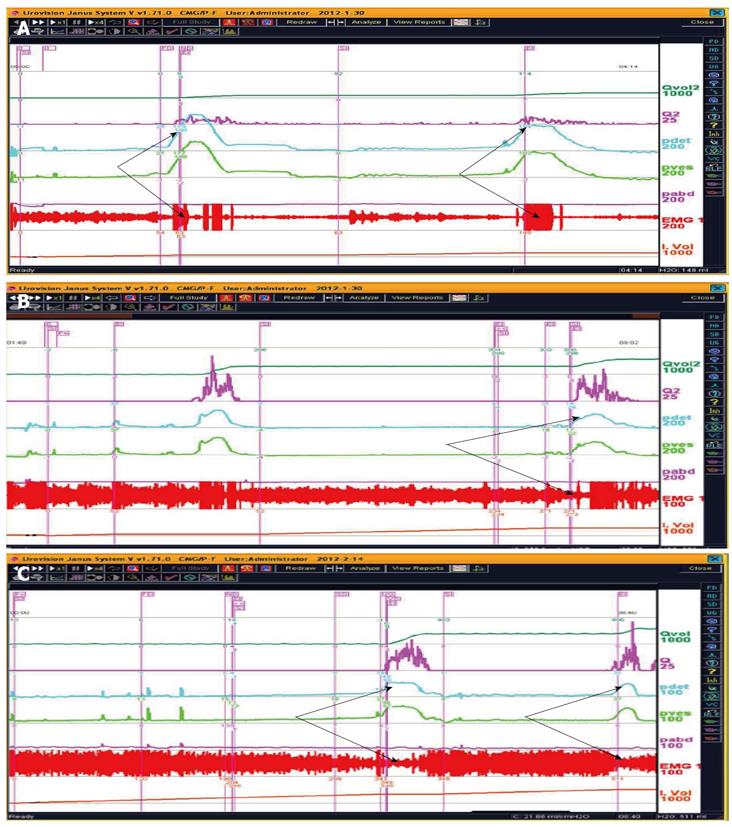

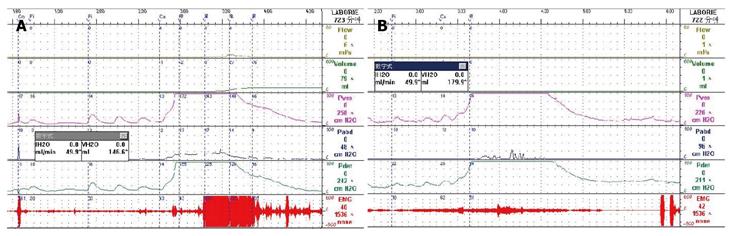

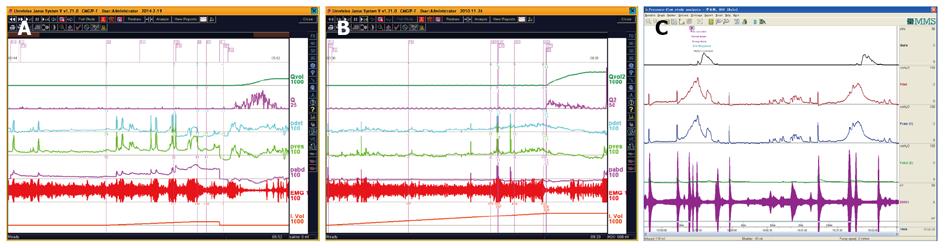

CMG-PFS-EMG curve: Normal CMG-PFS-EMG curve tells us how the bladder and urethra are performing storage function (bladder distention and urethra contraction) and how they are performing emptying function (at first the bladder contracts and the urethra actively relaxes[28], and then urinary flow produces). Active opening out of the urethra has major effects during emptying stage by stretching backwards the urethra and ceasing extension of urethral elasticity. So the external sphincter would actively relax during micturition: opening of the urethral tube, even to double the original diameter of the urethra[28]. After careful analysis and discussion of the UDS data, ideal options, such as IDO, ISO, DUA, SUI in LUTD, NDO, NSO (neurogenic sphincter overactivity, or detrusor-external sphincter dyssynergia, DESD), DUA in NLUTD, are produced. The process should be repeated more than one time if the curve is doubtful in order to gain a reproducible, stable and typical curve (Figures 9-11).

The main difference between NDO and IDO, or between NSO and ISO, is whether they are related to neurogenic origin or not. Grossly looking the patients may be non-neurogenic, just in the majority of patients with OAB (those with IDO), however, if more meticulous image examination, for example, brain functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), is undertaken, some positive findings could be found in patients with OAB or LUTD responsive to Interstim (sacral neuromodulation) treatment[29-31]. So many patients may be situated in the equivocal region between neurogenic and non-neurogenic LUTD.

There was some abnormal findings in fMRI in patients with Fowler’s syndrome who were responsive to the Interstim procedure[29]. The primary abnormality of the syndrome may be an overactive urethra[29]. This central reflex and sacral guarding reflex have the same nature.

As far as small-vessel diseases of the brain affecting the deep white matter were concerned, they may be associated with some bladder abnormalities. Generally speaking, when we cared for elderly OAB patients, both the brain and the bladder should be looked at[30,31].

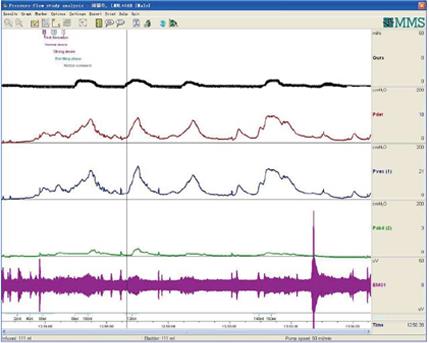

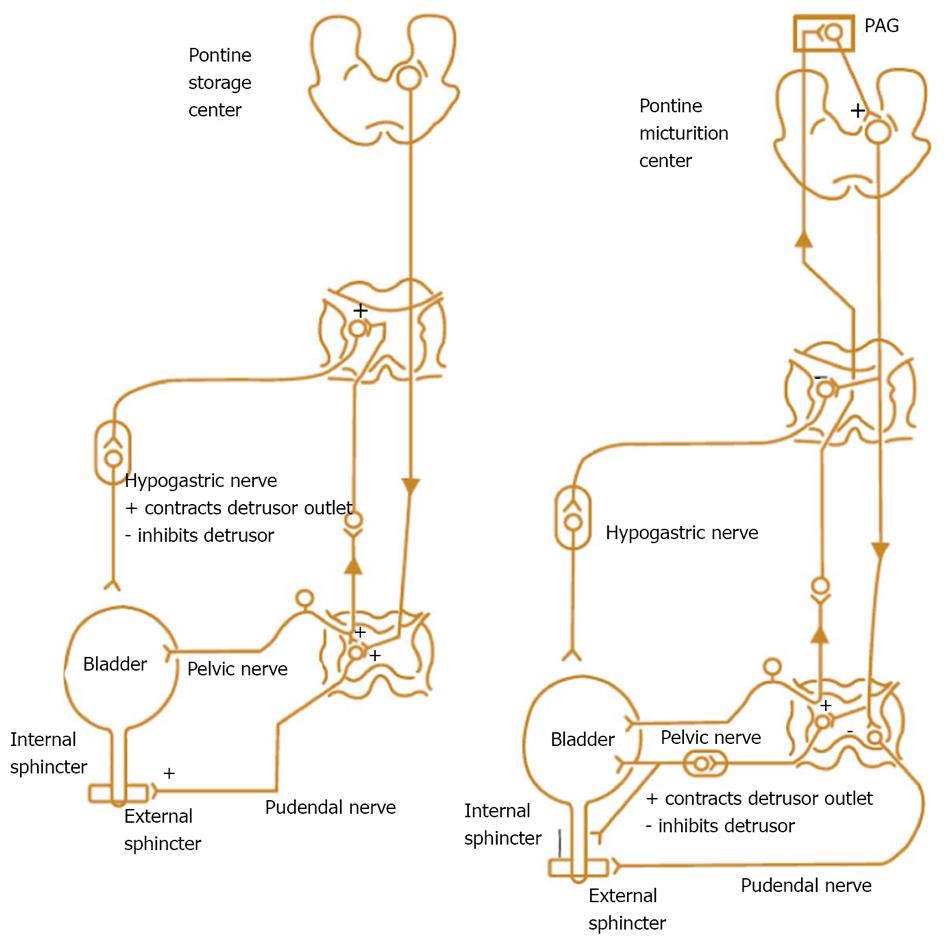

IDO and NDO may be treated by monotherapy or combination therapy[32-35]. And now, baclofen, a GABA agonist, may also go into the regimen[17,23]. Combination therapies with α1-blocker plus antimuscarinic, α1-blocker plus 5α-reductase inhibitor, α1-blocker plus PDE inhibitor, and α1-blocker plus 5-ARI have been attempted[32]. The pathophysiologic mechanisms and targets for pharmacotherapy for male LUTS, and nerve supply to the bladder and urethra are displayed below (Figures 12 and 13).

ISO and NSO are displayed by excellent EMG curves. Synonyms of ISO are dysfunctional voiding (DV), non-neurogenic neurogenic bladder, Fowler’s syndrome, and Hinman syndrome[38-40]. Chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO)[41] may co-exist with ISO.

In patients who complained of symptoms of frequency or urge may actually suffer from ISO, to which baclofen (a GABA-ergic receptor agonist) may be administered as a rational option and obtain good response shown by way of TL value[17,22].

Both storage and emptying symptoms may be caused by ISO. This double link could be explained by guarding reflex[8]. The storage symptom of the patient whose curve was shown in Figure 9 was resolved completely by administration of baclofen. Another female patient complained of urge incontinence for 10 yrs was also cured with baclofen after being confirmed as ISO (Figure 14). A woman aged 26 years complaining of poor-weak flow, voiding difficulty, intermittent or continuous catheterization for 18 years, and even receiving transurethral resection of the bladder neck twice, was also confirmed as ISO (Figure 15). She was eventually cured with baclofen too.

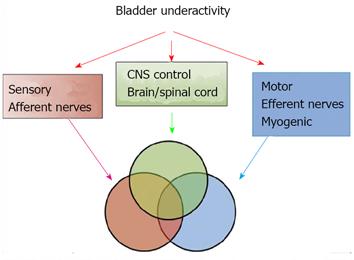

DUA and low compliance curve: DUA, either associated with NLUTS or LUTS, is known as detrusor underactivity, bladder underactivity, underactive bladder, or bladder underactivity/underactive bladder syndrome, either in analogy with the ICS definition of overactive bladder syndrome or not[42,43]. There are many different options as to its terminology, definition, and diagnostic methods. The approach is needed now to gain a consensus on these elements to allow standardisation of the literature and the development of optimal management[43]. No matter what the cause is, the main task of UDS is to show how the detrusor works: either unable to contract or relying on abdominal strain (Figure 16). DUA is associated with dysfunction of the sensory (afferent) nerve, the central nervous system (CNS), the efferent nerve and the target organ, the vesical detrusor itself. Furthermore, impaired voiding function has an age-associated prevalence[42] (Figure 17). As to the treatment of patients with DUA of any cause, the combination therapy (Chinese medicinal herbs, baclofen, and pyridostigmine) and continuous bladder drainage are proposed as feasible options[17]. After UDS, the patients with UDS patterns F and G could not pass urine at all and still needed catheterization, urinary diversion or even artificial urinary sphincter[44], but 56% and 12% of those with patterns F and G had their patterns changed into E or C, respectively, after such conservative treatment. The main function of Chinese medicinal herbs (common clubmoss herb, toothed achyranthes root, semen vaccariae, and so forth) were relaxing the urethral sphincter, decreasing outlet resistance, and promoting diuresis. Baclofen was used to relax the overactive sphincter, and pyridostigmine was used to strengthen the detrusor. And perhaps, the most important thing was absolute resting of the bladder without tube clamping for more than 4-6 wk[17]. Low frequency electrotherapy is also a rational option for selected female DUA patients suffering from neuromuscular deficiency[45].

Normal compliance is more than 10 mL/cmH2O[46]. Low compliance could co-exist with or without DUA in patients with LUTS or NLUTS. The low bladder compliance patterns in patients with NLUTD had three groups[46]: gradual increase, Group A; terminal increase, Group B; abrupt increase and plateau, Group C. Careful analysis seeking for dominant disorder of the detrusor or sphincter is vital for the patients. Little or no detrusor contraction is needed for complete voiding in some women in whom normal sphincter relaxation is enough to finish the micturition process. These patients are considered to be “normal”[47]. This occult modality of DUA should be considered as asymptomatic DUA (Figure 18 A and B). Furthermore, in male patients with DUA and low compliance potentially related to neurogenic lesions, this pattern of voiding could occur too (Figure 18C).

Low compliance may lead to bilateral hydronephrosis in patients suffering from diabetes insipidus. We found that children with polyuria, nocturnal enuresis and MRI-confirmed pituitary abnormality (hypointensities on T1-weighted MRI) and diabetes insipidus usually had hydroureteronephrosis, enlarged bladder capacity and low bladder compliance at second-half storage phase. Their detrusor and sphincter function had to be evaluated carefully as the first procedure. If the detrusor could contract and sphincter could relax during the voiding phase, the prognosis is good (Figure 19), and vice versa.

Different opinions existed about the newly constructed somatic-autonomic reflex for patients complaining of dysuria and incontinence after spinal cord injury or with tethered spinal cord[48,49]. Whether the operation succeeds or not depends upon the exhibition of detrusor contraction and sphincter dyssynergia or synergia. We have shown the detrusor contraction with or without sphincter overactivity in some patients suffering from SCI who received a successful artificial somatic-autonomic reflex for bladder control in this institution (Figure 20).

UPP curve: UPP examination is one of the UDS menus and cannot be omitted casually. The UPP curve gives us functional parameter of the urethra and its morphological evaluation, which is very useful for surgical selection of male BPH patients (Figure 21).

UDS findings other than abnormality, in short, subnormal or equivocal UDS findings, may lead to further seeking for potential pathologic factors. At this stage, cystourethroscopic examination, mucus membrane biopsies or imaging study of the LUT, and consult of associated physicians are necessary. Acidophilic cystitis[50] (Figure 22), slight bladder neck contracture, and glandular cystitis may be the possible responsive factors. In female and young male patients, BOO may be associated with inflammation of the bladder neck. In these patients, bladder neck obstruction or contracture, primary or secondary to longstanding ISO, squamous metaplasia or glandular cystitis-like appearance of the bladder neck are always observed. The lining of the bladder neck demonstrates a nontransitional epithelial appearance with epidermoid (squamous metaplasia) or glandular (adenomatous metaplasia) development and later formation of von Brunn’s nests in the lamina propria. Squamous metaplasia or glandular cystitis-like lesions in the bladder neck may be responsible for primary bladder neck obstruction in female or young male patients. PFS data gained during emptying phase could reveal the nature of obstruction more precisely (Figure 23).

LUTS may display ahead of schedule in some disease related or not related with LUT. Multiple system atrophy (MSA), multiple sclerosis (MS), spinal cord tumors, idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH)[51,52] and other occult neurogenic lesions may be responsible for slight degree of DUA or incontinence in some patients (Figure 24). Two patients presented in Figure 23 showed extra or intra-LUT symptoms: incontinence (A) and hydronephrosis (B). The former was proved as MSA two years later after our first consultation, and the potential neurogenic lesion of the latter has not been found so far. Perhaps functional MRI of the nervous system or some forthcoming techniques may aid diagnosis. Whether or not the patients complained of incontinence or hydronephrosis depends on the safe volume of the bladder (bladder volume before Pdet reaches 40 cmH2O) irrespective of the existence of vesico-ureteral reflux. If the functional bladder capacity exceeds it, both conditions will occur. If the functional capacity is less than the safe volume, distention of the upper urinary tract will not emerge. The latter patient had no imaging confirmed vesico-ureteral reflux indeed. However, bilateral nephrostomies were undertaken because of severe hydronephrosis at our first consultation.

Clear definition of UDS entities by means of cutoff values is ideal; however, descriptive recording is often more preferable in practice. TL value is a clear cutoff value for diagnosis of ISO or NSO. By overall view of the whole performance process of micturition (i.e., both the detrusor and sphincter during storage and emptying phases), normal or abnormal UDS findings give us concrete and demonstrable contour of LUTS entities, such as NA, IDO, ISO, DUA, NDO, NSO, BOO and SUI, guide the further option if LUTS and UDS findings are inadequate to explain the disease, and make us be convinced of the present medical state since in some cases extra or intra-LUT symptoms and UDS findings precede pathological abnormality.

P- Reviewers: Mazaris E, Sacco E, Valdevenito JP S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Nager CW, Brubaker L, Litman HJ, Zyczynski HM, Varner RE, Amundsen C, Sirls LT, Norton PA, Arisco AM, Chai TC. A randomized trial of urodynamic testing before stress-incontinence surgery. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1987-1997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | van Leijsen SA, Kluivers KB, Mol BW, Broekhuis SR, Milani AL, Bongers MY, Aalders CI, Dietz V, Malmberg GG, Vierhout ME. Can preoperative urodynamic investigation be omitted in women with stress urinary incontinence? A non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:1118-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McConnell JD. Why pressure-flow studies should be optional and not mandatory studies for evaluating men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1994;44:156-158. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Gerber GS. The role of urodynamic study in the evaluation and management of men with lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1996;48:668-675. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lose G, Klarskov N. Utility of invasive urodynamics before surgery for stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lose G; NICE. Urinary incontinence. The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guidline 40. 2006;40 Available from: http: //www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG40NICEguideline.pdf. |

| 7. | Agur W, Housami F, Drake M, Abrams P. Could the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines on urodynamics in urinary incontinence put some women at risk of a bad outcome from stress incontinence surgery? BJU Int. 2009;103:635-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Qu CY, Xu DF, Wang CZ, Chen J, Yin L, Cui XG. Anal sphincter electromyogram for dysfunction of lower urinary tract and pelvic floor. Advances in Applied Electromyography. Rijeka: InTech 2011; 161-188 Available from: http: //www.intechopen.com/articles/show/title/anal-sphincter-electromyogram-for-dysfunction-of-lower-urinary-tract-and-pelvic-floor. |

| 9. | Wessels SG, Heyns CF. Prospective evaluation of a new visual prostate symptom score, the international prostate symptom score, and uroflowmetry in men with urethral stricture disease. Urology. 2014;83:220-224. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kim SH, Oh SA, Oh SJ. Voiding diary might serve as a useful tool to understand differences between bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis and overactive bladder. Int J Urol. 2014;21:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Warren JW, Diggs C, Horne L, Greenberg P. Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: what do patients mean by “perceived” bladder pain? Urology. 2011;77:309-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu DF, Qu CY, Ren JZ, Jiang HH, Yao YC, Min ZL, Zhu YH, Chao L. Impact of tension-free vaginal tape procedure on dysfunctional voiding in women with stress urinary incontinence. Int J Urol. 2010;17:346-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cole EE, Dmochowski RR. Office urodynamics. Urol Clin North Am. 2005;32:353-370, vii. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Rollema HJ, Van Mastrigt R. Improved indication and followup in transurethral resection of the prostate using the computer program CLIM: a prospective study. J Urol. 1992;148:111-115; discussion 111-115. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Stöhrer M, Blok B, Castro-Diaz D, Chartier-Kastler E, Del Popolo G, Kramer G, Pannek J, Radziszewski P, Wyndaele JJ. EAU guidelines on neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2009;56:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Wein AJ. Pathophysiology and categorization of voiding dysfunction. editors. Campbell’s Urology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders 1998; 917-926. |

| 17. | Xu D, Cui X, Qu C, Yin L, Wang C, Chen J. Urodynamic pattern distribution among aged male patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of bladder outlet obstruction. Urology. 2014;83:563-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Emberton M, Gravas S, Michel MC, N’dow J, Nordling J, de la Rosette JJ. EAU guidelines on the treatment and follow-up of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol. 2013;64:118-140. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Wang C, Qu C, Chen J, Yin L, Xu D, Cui X, Yao Y. Urodynamic features of female patients with non-neurogenic lower urinary tract symptoms. Neurourol Urodynam. 2012;31:737-739. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Blaivas J, Chancellor M, Weins J, Verhaaren M. Atlas of Urodynamics. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing 2007; 69-82. |

| 21. | Mahajan ST, Fitzgerald MP, Kenton K, Shott S, Brubaker L. Concentric needle electrodes are superior to perineal surface-patch electrodes for electromyographic documentation of urethral sphincter relaxation during voiding. BJU Int. 2006;97:117-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xu D, Qu C, Meng H, Ren J, Zhu Y, Min Z, Kong Y. Dysfunctional voiding confirmed by transdermal perineal electromyography, and its effective treatment with baclofen in women with lower urinary tract symptoms: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial. BJU Int. 2007;100:588-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Xu DF, Min ZL, Qu CY. Comparisons of urodynamic findings and surgical results in stress urinary incontinence female patients with or without dysfunctional voiding. Eur Urol Suppl. 2009;8:314. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | O’Donnell PD. Electromyography. Practical Urodynamics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders company 1998; 65-71. |

| 25. | Digesu GA. Are the measurements of water-filled and air-charged catheters the same in urodynamics? Response to comments. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kondo Y, Homma Y, Takahashi S, Kitamura T, Kawabe K. Transvaginal ultrasound of urethral sphincter at the mid urethra in continent and incontinent women. J Urol. 2001;165:149-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kim YH, Boone TB. Voiding pressure flow studies. Practical Urodynamics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders company 1998; 52-64. |

| 28. | Petros PE, Bush M. Active opening out of the urethra questions the basis of the Valentini-Besson-Nelson mathematical model. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1585-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kavia R, Dasgupta R, Critchley H, Fowler C, Griffiths D. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of the effect of sacral neuromodulation on brain responses in women with Fowler’s syndrome. BJU Int. 2010;105:366-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sakakibara R, Panicker J, Fowler CJ, Tateno F, Kishi M, Tsuyusaki Y, Yamanishi T, Uchiyama T, Yamamoto T, Yano M. Is overactive bladder a brain disease? The pathophysiological role of cerebral white matter in the elderly. Int J Urol. 2014;21:33-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Krhut J, Holy P, Tintera J, Zachoval R, Zvara P. Brain activity during bladder filling and pelvic floor muscle contractions: a study using functional magnetic resonance imaging and synchronous urodynamics. Int J Urol. 2014;21:169-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lepor H. Combination therapy for non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms: 1 + 1 does not equal 2. Eur Urol. 2013;64:244-246; discussion 244-246. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Füllhase C, Chapple C, Cornu JN, De Nunzio C, Gratzke C, Kaplan SA, Marberger M, Montorsi F, Novara G, Oelke M. Systematic review of combination drug therapy for non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol. 2013;64:228-243. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Nitti VW, Auerbach S, Martin N, Calhoun A, Lee M, Herschorn S. Results of a randomized phase III trial of mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder. J Urol. 2013;189:1388-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sawada N, Nomiya M, Hood B, Koslov D, Zarifpour M, Andersson KE. Protective effect of a β3-adrenoceptor agonist on bladder function in a rat model of chronic bladder ischemia. Eur Urol. 2013;64:664-671. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Olujide LO, O’Sullivan SM. Female voiding dysfunction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19:807-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Soler R, Andersson KE, Chancellor MB, Chapple CR, de Groat WC, Drake MJ, Gratzke C, Lee R, Cruz F. Future direction in pharmacotherapy for non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol. 2013;64:610-621. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Fowler CJ, Christmas TJ, Chapple CR, Parkhouse HF, Kirby RS, Jacobs HS. Abnormal electromyographic activity of the urethral sphincter, voiding dysfunction, and polycystic ovaries: a new syndrome? BMJ. 1988;297:1436-1438. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Hinman F. Nonneurogenic neurogenic bladder (the Hinman syndrome)--15 years later. J Urol. 1986;136:769-777. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Carlson KV, Rome S, Nitti VW. Dysfunctional voiding in women. J Urol. 2001;165:143-147; discussion 143-147. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Elneil S. Urinary retention in women and sacral neuromodulation. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21 Suppl 2:S475-S483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Osman NI, Chapple CR, Abrams P, Dmochowski R, Haab F, Nitti V, Koelbl H, van Kerrebroeck P, Wein AJ. Detrusor underactivity and the underactive bladder: a new clinical entity? A review of current terminology, definitions, epidemiology, aetiology, and diagnosis. Eur Urol. 2014;65:389-398. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Verghese T, Latthe P. Recent status of the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int J Urol. 2014;21:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Xu DF, Zhang S, Wang CZ, Li J, Qu CY, Cui XG, Zhao SJ. Low-frequency electrotherapy for female patients with detrusor underactivity due to neuromuscular deficiency. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:1007-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Park WH. Management of low compliant bladder in spinal cord injured patients. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. 2010;2:61-70. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | van Koeveringe GA, Rahnama’i MS, Berghmans BC. The additional value of ambulatory urodynamic measurements compared with conventional urodynamic measurements. BJU Int. 2010;105:508-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Xiao CG. Reinnervation for neurogenic bladder: historic review and introduction of a somatic-autonomic reflex pathway procedure for patients with spinal cord injury or spina bifida. Eur Urol. 2006;49:22-28; discussion 28-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lin H, Hou C, Chen A, Xu Z. Innervation of reconstructed bladder above the level of spinal cord injury for inducing micturition by contractions of the abdomen-to-bladder reflex arc. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:948-952; discussion 952. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Xu D, Liu Y, Gao Y, Zhao X, Qu C, Mei C, Ren J. Glucocorticosteroid-sensitive inflammatory eosinophilic pseudotumor of the bladder in an adolescent: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Mirzayan MJ, Luetjens G, Borremans JJ, Regel JP, Krauss JK. Extended long-term (& gt; 5 years) outcome of cerebrospinal fluid shunting in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:295-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Takaya M, Kazui H, Tokunaga H, Yoshida T, Kito Y, Wada T, Nomura K, Shimosegawa E, Hatazawa J, Takeda M. Global cerebral hypoperfusion in preclinical stage of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. J Neurol Sci. 2010;298:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |