Published online Feb 8, 2018. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v7.i1.56

Peer-review started: January 4, 2017

First decision: March 13, 2017

Revised: August 3, 2017

Accepted: December 4, 2017

Article in press: December 4, 2017

Published online: February 8, 2018

Processing time: 403 Days and 4.6 Hours

To assess the knowledge of general pediatricians througout Indonesia about the diagnosis and treatment of childhood constipation.

A comprehensive questionnaire was distributed to general pediatricians from several teaching hospitals and government hospitals all over Indonesia.

Data were obtained from 100 pediatricians, with a mean of 78.34 ± 18.00 mo clinical practice, from 20 cities throughout Indonesia. Suspicion of constipation in a child over 6 mo of age arises when the child presents with a decreased frequency of bowel movements (according to 87% of participants) with a mean of one bowel movement per 3.59 ± 1.0 d, hard stools (83%), blood in the stools (36%), fecal incontinence (33%), and/or difficulty in defecating (47%). Only 26 pediatricians prescribe pharmacologic treatment as first therapeutic approach, while the vast majority prefers nonpharmacologic treatment, mostly (according to 68%) The preferred nonpharmacologic treatment are high-fiber diet (96%), increased fluid intake (90%), toilet training (74%), and abdominal massage (49%). Duration of non-pharmacological treatment was limited to 1 to 2 wk. Seventy percent of the pediatricians recommending toilet training could only mention some elements of the technique, and only 15% was able to explain it fully and correctly. Lactulose is the most frequent pharmacologic intervention used (87% of the participants), and rectal treatment with sodium citrate, sodium lauryl sulfo acetate, and sorbitol is the most frequent rectal treatment (85%). Only 51% will prescribe rectal treatment for fecal impaction. The majority of the pediatricians (69%) expect a positive response during the first week with a mean (± SD) of 4.1 (± 2.56) d. Most participants (86%) treat during one month or even less. And the majority (67%) stops treatment when the frequency and/or consistency of the stools have become normal, or if the patient had no longer complaints.

These data provide an insight on the diagnosis and management of constipation in childhood in Indonesia. Although general pediatricians are aware of some important aspects of the diagnosis and mangement of constipation, overall knowledge is limited. Efforts should be made to improve the distribution of existing guidelines. These findings highlight and confirm the difficulties in spreading existing information from guidelines to general pediatricians.

Core tip: Diagnosis and management of functional constipation in children by general paediatricians is suboptimal because of a lack of knowledge of published guidelines. Our data confirm that efforts should be made to improve distribution of existing guidelines to primary health care.

- Citation: Widodo A, Hegar B, Vandenplas Y. Pediatricians lack knowledge for the diagnosis and management of functional constipation in children over 6 mo of age. World J Clin Pediatr 2018; 7(1): 56-61

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v7/i1/56.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v7.i1.56

Constipation is worldwide a common problem in children. Three to five percent of all clinic consultations to pediatricians are due to constipation, and the number keeps increasing[1]. Primary care physicians such as pediatricians or family physicians are frequently consulted by parents because of constipation[2]. Scientific societies develop clinical practice guidelines with the goal to improve diagnosis and management and result in a better quality of care. However, these recommendatations from scientific societies are not easily picked up by primary health care level[3]. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of constipation, both for adults and children, have been published by professional associations such as the North American and European Societies of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN)[4]. Not many studies were conducted in Indonesia, but it has been estimated that the prevalence of constipation ranges between 12% and 48%, depending on multiple variables[5,6]. Although constipation is rarely an emergency, when it is not managed properly it can cause serious complications in the long term such as significant abdominal pain, lowered self-esteem, depression, and decreased quality of life[4,7]. Functional constipation has been identified as an important health problem during childhood and contrary to common belief, has a significant impact on quality of life of children and their families[8]. There is currently no Indonesian guideline. This study aims to evaluate the diagnosis and quality of management of constipation in children among pediatricians in Indonesia, in order to include our findings in National Guidelines.

We developed a comprehensive anonymous questionnaire consisting of both multiple-choice and open questions (Table 1: Questionnaire). The questionnaires were distributed to 103 general pediatricians during a national meeting of the Indonesian Society of Pediatrics, both from academic and non-academic centers, working in 20 different cities in Indonesia. They were asked to fill in the questionnaire on the spot and returned the document as soon as it was completed to the research staff.

| We are studying the diagnostic criteria and management of constipation in children over 6 months of age. This questionnaire will be handled anonymously. Please tell us more about your experience in dealing with children with constipation. Many aspects in the diagnosis and management of constipation are debated. Therefore, there is no right or wrong answer. We look forward to your participation in completing this short questionnaire, which will take you around 5 to 10 min. |

| 1 Please specify your profession: General Pediatrician Yes / No |

| How long are you working as General Pediatrician? ___ year(s) and __ month(s) |

| In which city do you work?______________ |

| 2 Which criteria do you use to diagnose constipation in children older than 6 months? (more than one answer is possible): |

| o Infrequent defecation, less than once in every ____ day(s) |

| o Hard consistency of stool |

| o Bleeding when passing stools |

| o Fecal incontinence |

| o Difficulties in defecation |

| o Crying before passing stool with normal consistency |

| o Other (please specify) |

| 3 Which treatment do you recommend as first approach? (more than one answer is possible): |

| o Take a high-fiber diet |

| o Increase fluid intake |

| o Apply abdominal massage for babies |

| o Start appropriate toilet training |

| o Other (please specify)____________________________ |

| 4 If you answered “toilet training” in question 3, please explain briefly the method of toilet training which you suggested : |

| 5 When do you start pharmacological therapy in a constipated child > 6 months old? |

| o Immediately when the diagnosis of constipation is established |

| o If non-pharmacological treatment does not respond after _____ day(s)/ week(s)/ month(s) |

| o I do not recommendany pharmacological therapy |

| o Other (please specify) _______________________________ |

| 6 The pharmacological treatment that I recommend is : |

| o Lactulose |

| o Sorbitol |

| o Magnesium salt |

| o Laxative suppository |

| o Other (please specify) _____________________________ |

| 7 The rectal pharmacological treatment that you mostly recommend is: |

| o Enema with a combination of sodium citrate, sodium lauryl sulfoacetate, and sorbitol (Microlax®) |

| o Trifenylmethaan (Dulcolax®) |

| o Docusate Sodium, Sorbitol (Yal®) |

| o Glycerin suppository |

| o I do not recommend such treatment |

| o Other (please specify) ___________________________________________ |

| 8 When do you recommend rectal treatment? |

| o When impacted feces are diagnosed on physical examination |

| o When patient had no bowel movement during ____ days |

| o When stool is too hard to pass |

| o When patient has to much difficulties to produce stools |

| o Other (please specify) _________________________ |

| 9 Is there any other information/ education that you provide to the patients/parents? |

| 10 In average, how long does it take for your patients to show a positive response to your first therapeutic approach? _________ days/ week(s)/ month(s) |

| 11 In average, how long do you treat your patients for constipation? _______ week(s)/ month(s)/year(s) |

| 12 When do you stop treatment? |

| Thank you so much for your participation |

The first series of question asks about the symptoms making the pediatrician suspicious of the possible diagnosis constipation as cause for the symptoms. Participants could indicate more than one symptom out of a proposed list: Number of bowel movements, consistency of the stools, difficulties in defecation, blood in the stools, encopresis… The second series of questions regarded treatment, duration of treatment, and outcome. Specific information about recommendations regarding toilet training was asked for as an open question.

The response rate was 97%; 3 out of 103 general pediatricians returned the questionnaire with incomplete answers. The participants worked as general pediatricians for a mean duration of 78.34 ± 18.00 mo in hospitals distributed over the Western, Middle, and Eastern parts of Indonesia.

The pediatricians suspected constipation when a child over 6 mo of age presents with a decrease in frequency of bowel movement (87% of the participants) with a mean of 3.59 ± 1.0 d between two defecations (Question 1), hard stools (83%), presence of blood in the stools (36%), encopresis (33%), and/or difficulty in defecating (47%) (Table 2).

| Symptom at presentation | Frequency |

| Decreased bowel movement | 87% |

| Hard stool | 83% |

| Difficulties in defecation | 47% |

| Blood in stool | 36% |

| Encopresis | 33% |

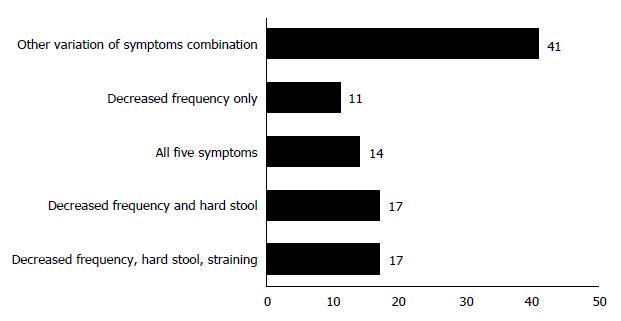

Seventeen participants (17%) did choose a combination of symptoms: Decreased frequency, hard stool and difficulties in defecation. Another 17 pediatricians chose only decreased frequency and hard stools. Eleven percent indicated only decreased frequency, while 14% answered they considered any of the symptoms or any combination as possibly indicating the diagnosis of constipation. Other participants combined any other variation of symptoms (Figure 1).

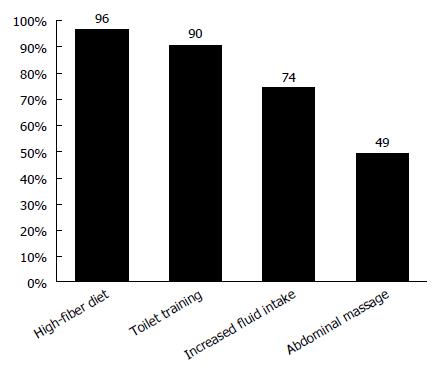

Regarding treatment, only 26% of the general pediatricians prescribed pharmacologic treatment as a first option. Non-pharmacologic treatment was recommended for a period of one to two weeks by 68% of the participants: high-fiber diet (96% of the participants), increased fluid intake (90%), toilet training (74%) and abdominal massage (46%) (Figure 2). However, seventy percents of the pediatricians indicating toilet training as therapeutic intervention could mention only some elements of the toilet training recommendations for constipated children. Only 15% were able to explain it fully and correctly, which includes age-appropriate technique and timing for toilet training according to the guidelines published by NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN[4]. Lactulose was the most frequent (87% of participants) pharmacologic intervention used and a micro-enema with a combination of sodium citrate, sodium lauryl sulfoacetate and sorbitol was the most frequent rectal treatment (85%) prescribed. Only 51 of the pediatricians did recommend rectal treatment for fecal impaction. Some would only recommend rectal treatment after failure of lactulose.

The majority of the pediatricians (69%) answered to expect a positive response during the first week after starting therapy, with a mean (± SD) of 4.1 (± 2.56) d. Most participants (86%) recommend treatment during one month or even less. And the majority (67%) also stops the treatment when the frequency and/or consistency of the stools have become normal, or if the patient had no longer complaints.

Constipation is common during childhood and has an important impact on quality of life with a negative impact on psychological wellbeing. Functional constipation in young individuals influences quiet substantially familial stress[8]. The NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN Joint Guideline recommends the use of Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional constipation, based on history and physical examination[4]. The number of physician visits due to childhood constipation has doubled between 1958 and 1986[9]. About 3% of the visits to a general pediatric practice and as many as 30% of consultations to a pediatric gastroenterologists are because of sysmptoms suggestive for constipation[2]. Many authors have hypothesized that this important increase in childhood constipation might be due to changing patterns in toilet training, imbalanced diet, or that parents nowadays are more likely to consult because of symptoms of constipation.

Little is known about the knowledge of pediatricians (and general practitioners) on the diagnosis and management of childhood constipation or the management. In most children, constipation is usually associated with stool retention, incomplete evacuation of stool, and fecal incontinence[4]. Fecal incontinence is involuntary or voluntary passage of feces into the underwear or in socially inappropriate places[10]. Fecal incontinence is also known as encopresis and fecal soiling. In our study, only 33% of the respondents suspected childhood constipation in the presence of fecal incontinence. This is a major lack of knowledge as fecal incontinence is reported to occur in up to 29.6% of the children with of constipation[11]. According to other data, about 2% of an unsleected population suffers fecal incontinence, albeit relate dto constipation is as much as 82%[12]. According to data from a tertiary care center, as many as 85% of the children diagnosed with fecal impaction presented with fecal incontinence[13]. Thus, not recognizing this symptom fecal incontinence as aa symptom of constipation will lead to underdiagnosis of constipation.

Treatment success corresponds to how aggressively the child was treated. The Indonesians pediatricians expect a positive response to fast and treat over a to short period[4]. Any form of colonic evacuation followed by daily laxative therapy results in a better outcome than less aggressive management[2]. The long term efficacy of treatment remains an issue. After treatment during two months, more than one third (37%) is still considered as constipated[2]. Laxatives or stool softeners are the most used approach, in up to 87% of children. Frequent used laxatives are magnesium hydroxide (77%), senna syrup (23%), mineral oil (8%) and lactulose (8%)[2]. About 68% of the participants preferred non-pharmacological treatment as first intervention, before giving any medication. The rise in prevalence of constipation in the past decade may lead to speculations about the role of decreased fiber intake in constipation. We found a discrepancy in diet management between recommendations by the ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN guideline and the answers provided by the participants in our study. The guideline states that evidence does not support the use of extra fiber above the recommended intake in the treatment of functional constipation[4], while the majority of the Indonesian pediatricians recommended families a high-fiber diet (96%). However, at least in the Western world, most of the children do have a low fibre intake, resulting in a recommendation to increase the fibre intake up to the normal, recommended level. The efficacy of extra fibre has not been shown, mainly because it was poorly studied[4]. Therefore this dietary intervention cannot be recommended. However, data have never suggested that constipation worsened with a high fibre diet. As a consequence, the advice to have a high fibre diet should be considered as “not recommended”, but it does not mean that this recommendation is erroneous. The NASPGHAN/ESPGHAN guideline also mentions that extra fluid intake above the recommended intake has not been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of constipation, while most Indonesian participants recommended an increase in fluid intake (90%)[4]. The comment that was made regarding fibre can be repeated regarding water. Dietary modifications should only be done to ensure a balanced diet and so that sufficient fibers and fluid are consumed[4]. However, other authors had described the benefits of consuming a high dietary fiber[14].

Toilet training is a frequent non-pharmacologic treatment recommended by the pediatricians. Seventy percent of participants choosing toilet training could mention some elements of toilet training technique, but only 15% of them were able to explain it thoroughly and correctly. This is extremely detrimental as toilet training is proven to be beneficial to increase bowel movement[4,14]. Therefore, pediatricians should further enhance their knowledge on toilet training in order to give proper education to parents.

The management of constipation with fecal impaction should be conducted more aggressively. Literature suggests to use enemas or oral medication with poly-ethylene glycol to obtain fecal disimpaction[4,15]. Most of the participants (87%) recommended lactulose for disimpaction. As much as 26% of the pediatricians prefer rectal treatment as first option in the therapy. Impaction, if left untreated, may lead to involuntary overflow soiling and pain in passing stools. Therefore, general pediatricians should give a more intrusive approach in order to resolve fecal impaction. An electronic questionnaire which was developed to test the diagnostic and management approaches for functional constipation without or with fecal incontinence was send out to over 8000 persons[16]. Almost 1000 answered (80% trainees and 20% physicians). A large majority (84%) of the respondents acknowledged to not or insufficiently know about the NASPGHAN guidelines that were published in 2006[16]. A questionnaire testing the awareness of pediatric Rome criteria for the diagnosis of functional gastrointestinal disorders showed comparable results: Less than 30% of the general pediatricians knew about the Rome criteria, in contracts to almost all pediatric gastroenterologists[17]. Adequate dissemination of recommendations and guidelines is to be a major problem. These recommendations may be perceived as difficult and even inappropriate to implement. Physicians may simply also just not agree with some of the recommendations because of missing evidence. As a consequence, physicians may refuse to include recommendations from guidelines in their daily practice[18]. Functional constipation and functional gastrointestinal disorders are common problems. Childhood constipation does have a major impact on health care budgets: the management of childhood constipation is estimated to be cost about $2500/year[19].

A shortcoming of this research is that the questionnaire was not validated. in Another weakness of the design of this study is that no information was collected regarding the fibre and fluid intake at baseline. However, considering that the questionnaire collects information on the theoretical criteria used by pediatricians for the diagnosis and management of constipation, it was not possible to collect information on the daily fibre and fluid intake of Indonesian children (with constipation).

This study provides an insight of the pattern and quality of diagnosis and management of constipation in Indonesian children. Although constipation is a frequent condition, knowledge about appropriate diagnosis and treatment is weak among young general pediatricians. Non-evidence based advices are often given to patients and their family, resulting in less effective treatment. Especially fecal incontinence is insufficiently recognized as a symptom of constipation. The appropriate management of fecal impaction still needs to be stressed among pediatricians. Pediatricians need more comprehensive knowledge on proper toilet training advices to be able to teach patients. Therefore, the knowledge of general should be improved as well as the implementation regarding available constipation guidelines is important to be assessed to ensure early diagnosis and prompt treatment. Data from this research confirm that training regarding diagnosis and management of functional constipation is needed. A better knowledge of medication to obtain rapid solution of the problem, the need for effective disimpaction and erroneous considerations regarding adverse effects will improve the outcome[16]. Awareness campaigns informing the population about the magnitude and impact of childhood constipation have to be considered considering its social and economic impact[8]. A better dissemination of recommendations is a priority[18].

Criteria for the diagnosis and management of functional constipation are not well known by general pediatricians and primary health care, despite published guidelines.

Our research was limited to one country.

This research confirms the frequency of childhood constipation. Knowledge of primary health care physicians on the diagnosis and management is limited. Published guidelines are insufficiently disseminated.

It is likely that these findings can be extrapolated to the rest of the world, since similar data are reported for the United States and Indonesia.

Childhood constipation, electronic questionnaire, primary healthcare, guidelines, laxative.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: Indonesia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Maffei HVL, Malowitz S, Soylu OB S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li RF

| 1. | Biggs WS, Dery WH. Evaluation and treatment of constipation in infants and children. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73:469-477. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Borowitz SM, Cox DJ, Kovatchev B, Ritterband LM, Sheen J, Sutphen J. Treatment of childhood constipation by primary care physicians: efficacy and predictors of outcome. Pediatrics. 2005;115:873-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ebben RH, Vloet LC, Verhofstad MH, Meijer S, Mintjes-de Groot JA, van Achterberg T. Adherence to guidelines and protocols in the prehospital and emergency care setting: a systematic review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY, Faure C, Langendam MW, Nurko S, Staiano A, Vandenplas Y, Benninga MA; European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology. Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:258-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 545] [Cited by in RCA: 630] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bardosono S, Sunardi D. Functional Constipation and its related factors among female workers. Maj Kedokt Indon. 2011;61:126-129. |

| 6. | Prawono LA, Fauzi A, Syam AF, Makmun D. Paradigm on chronic constipation: pathophysiology, diagnostic, and recent therapy. Indonesian J Gastroenterol Hepatol Dig Endosc. 2012;13:174-180. |

| 7. | Rowan-Legg A; Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Committee. Managing functional constipation in children. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16:661-670. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Crispus Perera BJ, Benninga MA. Childhood constipation as an emerging public health problem. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6864-6875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:606-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, Walker LS. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527-1537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1150] [Cited by in RCA: 1077] [Article Influence: 56.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 11. | Nurko S, Scott SM. Coexistence of constipation and incontinence in children and adults. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:29-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Benninga MA. Constipation-associated and nonretentive fecal incontinence in children and adolescents: an epidemiological survey in Sri Lanka. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:472-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Loening-Baucke V. Functional fecal retention with encopresis in childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:79-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Catto-Smith AG. 5. Constipation and toileting issues in children. Med J Aust. 2005;182:242-246. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Bekkali NL, van den Berg MM, Dijkgraaf MG, van Wijk MP, Bongers ME, Liem O, Benninga MA. Rectal fecal impaction treatment in childhood constipation: enemas versus high doses oral PEG. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1108-e1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang CH, Punati J. Practice patterns of pediatricians and trainees for the management of functional constipation compared with 2006 NASPGHAN guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:308-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sood MR, Di Lorenzo C, Hyams J, Miranda A, Simpson P, Mousa H, Nurko S. Beliefs and attitudes of general pediatricians and pediatric gastroenterologists regarding functional gastrointestinal disorders: a survey study. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50:891-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sood MR. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of functional constipation: “are we there yet?”. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:288-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liem O, Harman J, Benninga M, Kelleher K, Mousa H, Di Lorenzo C. Health utilization and cost impact of childhood constipation in the United States. J Pediatr. 2009;154:258-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |