Published online Nov 8, 2016. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v5.i4.370

Peer-review started: June 20, 2016

First decision: July 27, 2016

Revised: August 27, 2016

Accepted: October 5, 2016

Article in press: October 9, 2016

Published online: November 8, 2016

Processing time: 140 Days and 11 Hours

To study the clinical profile and outcomes of pediatric endogenous endophthalmitis from a tertiary eye hospital in South India.

A total of 13 eyes of 11 children presented to us with varied symptoms and presentations of endogenous endophthalmitis, over a five-year period from January 2010 to December 2015 were studied. Except for two eyes of a patient, vitreous aspirates were cultured from all 11 eyes to isolate the causative organism. These eleven eyes also received intravitreal injections. All patients were treated with systemic antibiotics.

Two cases had bilateral endophthalmitis. Ages ranged from 4 d to 11 years. Five cases were undiagnosed and treated, before being referred to our center. Ten of the 13 eyes underwent a core vitrectomy. The vitrectomy was done at an average on the second day after presenting (range 0-20 d). Five of the 11 vitreous aspirates showed isolates. The incriminating organisms were bacteria in three and fungus in two. An underlying predisposing factor was found in seven patients. At a mean follow-up 21.5 mo, outcome was good in 7 eyes of 6 cases (54%), five eyes of four cases (38%) ended up with phthisis bulbi while one child died of systemic complications.

Endogenous endophthalmitis is a challenge for ophthalmologists. Early diagnosis and intervention is the key for a better outcome.

Core tip: It was a retrospective study of 13 eyes of 11 children with endogenous endophthalmitis, where a detailed evaluation of the clinical profile including the presenting symptoms, signs, incriminating organisms and outcomes were studied.

- Citation: Murugan G, Shah PK, Narendran V. Clinical profile and outcomes of pediatric endogenous endophthalmitis: A report of 11 cases from South India. World J Clin Pediatr 2016; 5(4): 370-373

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v5/i4/370.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i4.370

Endogenous endophthalmitis is a rare, but highly destructive infection of the eye, in which the pathogenic organisms reach through the systemic circulation. Studies have shown that endogenous endophthalmitis accounts for 2% to 8% of all endophthalmitis cases[1,2]. It is even rarer in children, and constitutes only 0.1% to 4% of all endogenous endophthalmitis cases[2,3]. In children it may masquerade as uveitis, pre septal orbital cellulitis, congenital glaucoma, conjunctivitis or retinoblastoma. It can also occur as a rare complication of neonatal sepsis. In a particular series in India from a tertiary hospital for every 1000 live births, 1 case of endophthalmitis was seen[4]. The incidence of neonatal endophthalmitis from the United States is about 4.42 cases per 100000 live births[5]. The reasons for the high incidence of endophthalmitis in Indian population may be because of more immunocompromised, poor hygiene and high rates of infection secondary to antibiotic resistant microbes[4]. We report a series of 11 chidren presenting with endogenous endophthalmitis at our institute over a period of five years.

This is a retrospective study of 13 eyes of 11 children who presented at Aravind Eye Hospital, Coimbatore with signs and symptoms of endogenous endophthalmitis. After taking a detailed history from all the patients, a through ocular examination was done. Visual acuity was taken for all cooperative cases. This was followed by through anterior examination using slip lamp biomicroscopy. Fundus examination was done with indirect ophthalmoscopy. B scan ultrasonography was done for all cases with a hazy media. Short general anesthesia was administered to children who very not cooperative for a through ocular examination. Cases with severe infection were immediately posted for vitreous biopsy with or without core vitrectomy with intravitreal antibiotic injections. All were given systemic antibiotics. All vitreous aspirates were cultured at the microbiology department of Aravind Eye Hospital, Coimbatore. A thorough systemic examination was undertaken with the help of a paediatrician to look for any precipitating factors. A good outcome was defined as maintenance of ocular anatomy with functional vision at the end of treatment.

Two cases had bilateral disease. There were 5 females and 6 males. The mean age was 43 mo (range 4 d to 132 mo). Ten cases (91%) presented with swelling, pain and redness in the eyes. Ten of the 13 eyes underwent a vitreous biopsy with core vitrectomy and intravitreal antibiotics injection. One patient underwent only a vitreous tap with lens aspiration for a lens abscess with intravitreal antibiotics. Two eyes of another patient who suffered from a multifocal retinochoroidal infiltrate secondary to septic arthritis recovered with systemic antibiotics alone. Eleven vitreous aspirates were cultured to isolate the causative organism. The mean time from the onset of symptoms to presentation was 11 d (range 3-30 d). Five cases were undiagnosed by the treating ophthalmologist, before being referred to our center. Of these two were being treated as uveitis, two as conjunctivitis and one as suspected retinoblastoma. There did not seem to be a prediliction for either eye with an almost equal distribution of 5 left and 4 right eyes. Both the eyes were affected in two patients. Five of the 11 vitreous taps showed isolates. The incriminating organisms were fungi in two and bacteria in remaining three (Table 1). Core vitrectomy was done in 10 eyes at a mean of second day after presentation (range 0-20 d).

| Case | Age (mo) | Sex | Eye | Vitreous growth | Systemic affection | Follow-up (mo) | Final outcome | |

| Focus | Growth | |||||||

| 1 | 24 | M | LE | Aspergillus flavus | Broncho pneumonia, meningitis with cerebral abscess | Aspergillus flavus | 1 | Death |

| 2 | 132 | M | LE | Nil | - | - | 48 | Good |

| 3 | 48 | M | LE | Neisseria meningitides | Fever | - | 44 | Good |

| 4 | 36 | F | RE | Nil | URI | 7 | Phthisis bulbi | |

| 5 | 1 | F | BE | - | Knee arthritis | - | 26 | Good |

| 6 | 7 | M | LE | Candida | Pre term | 9 | Phthisis bulbi | |

| 7 | 48 | F | RE | Staphylococci | Fever with cough | 24 | Good | |

| 8 | 41 | M | BE | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Hand abscess | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 48 | Phthisis bulbi |

| 9 | 108 | M | LE | Nil | - | - | 9 | Good |

| 10 | 24 | F | RE | Nil | - | 18 | Good | |

| 11 | 48 | F | RE | Nil | Fever with URI | 3 | Phthisis bulbi | |

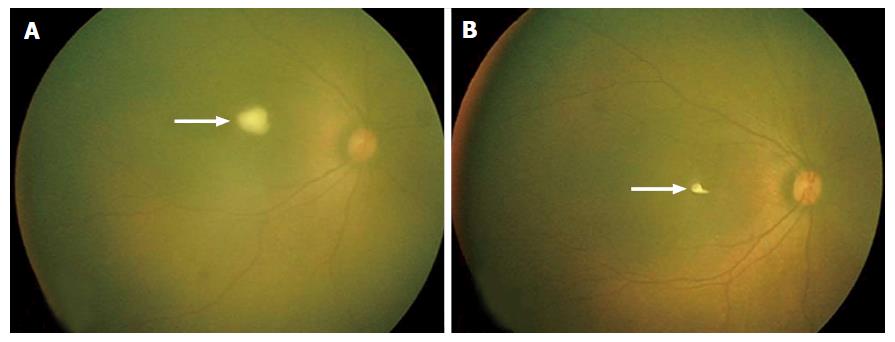

A positive blood culture was seen only in case 8 which grew pseudomonas in blood, vitreous and also from the hand abscess. An underlying predisposing factor was found in seven patients. Case 1, who developed endophthalmitis secondary to broncho pneumonia and meningitis, the vitreous tap and the cerebrospinal fluid both tested positive for Aspergillus. This child met a fatal end within two weeks of presenting to us due to his systemic condition. Case 5 was referred with a suspected diagnosis of retinoblastoma. Child had multiple small yellowish retinal lesions over posterior pole and periphery in both eyes with a history of septic arthritis. The ocular lesions resolved completely with systemic antibiotics only (Figure 1). Good outcome was seen in 7 eyes of 6 cases (54%), of which final visual acuity of ≥ 6/9 was seen in 5 eyes and ≤ 6/36 in 2 eyes. Five eyes of 4 cases ended up with phthisis bulbi and one child died of systemic complications.

Detection of endogenous endophthalmitis is based on a through history and a good ocular examination. Early detection of endophthalmitis in children is really challenging because they may not be able to identify or express their symptoms. On top of that, it is usually not easy to carry out a thorough ocular examination. Though there have been innumerable studies on adult onset endogenous endophthalmitis there is limited literature in pediatric group. In the study by Basu et al[4] six premature infants with extremely low birth weight developed endogenous endophthalmitis. They reported Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in two cases each and Candida albicans and Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in one case each. Three of the 6 cases died in their series and remaining 2 infants retained good vision and one ended up with phthisis bulbi. Our study had two neonates of which one was proven to be pseudomonas. There was one death in our study and 5 (38%) eyes went for phthisis bulbi.

Wrong diagnosis at the time of referral is reportedly seen in 16% to 63% of cases, thus delaying the proper treatment[6,7]. In our study 5/11 cases (45%) were referred to us with a wrong diagnosis, which were, two as uveitis, two as conjunctivitis and one as retinoblastoma. Common sources of infection in endogenous endophthalmitis in children include distal wound infection, meningitis, which was seen in one case each in our study, intravenous catheters, endocarditis and urinary tract infections[8,9]. In United States, the rate of endogenous endophthalmitis from septicemia declined from 8.71 cases in 1998 to only 4.42 cases per 100000 live births in 2006, which is a 6% decrease per year[5]. This may be due to the improvement in neonatal care and the advent of effective broad spectrum antibiotics in the treatement of septicemia. A major review of pediatric infectious endophthalmitis by Khan et al[8] found Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species as the most common cause of post-traumatic and post-operative endophthalmitis and Candida albicans for endogenous endophthalmitis. We had two cases with fungal infection in our study.

In conclusion, endogenous endophthalmitis in children is a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for ophthalmologists. It can occur at any age, and in either sex. Since there is a usually a septic foci, systemic antibiotics seem to play a much definitive role in treatment. Inspite of early diagnosis and treatment, 1/3rd of patients can still have a dismal outcome.

Pediatric endogenous endophthalmitis is a devastating infection of the eye which can lead to permanent blindness.

Although a blinding condition, early diagnosis and treatment can save the eye and vision.

Finding the source of infection is important as this may lead to a quicker recovery. Apart from systemic antibiotics, core vitrectomy with intravitreal antibiotic injections by a retinal surgeon may improve the prognosis, as seen in the present study.

The study results suggest that prompt and correct diagnosis and treatment can lead to better outcome.

Endogenous endophthalmitis is a severe and serious infection of the eye where the source of infection is from a distal organ. The infective organisms reach the ocular tissues via the blood stream.

This study has valuable data that would be of interest if published. It is well written and comprehensive.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Inan UU, Nowak MS, Shih YF, Tzamalis A S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Chee SP, Jap A. Endogenous endophthalmitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rachitskaya AV, Flynn HW, Davis JL. Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by salmonella serotype B in an immunocompetent 12-year-old child. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:802-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chaudhry IA, Shamsi FA, Al-Dhibi H, Khan AO. Pediatric endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: case report and review of the literature. J AAPOS. 2006;10:491-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Basu S, Kumar A, Kapoor K, Bagri NK, Chandra A. Neonatal endogenous endophthalmitis: a report of six cases. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1292-e1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moshfeghi AA, Charalel RA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Morton JM, Moshfeghi DM. Declining incidence of neonatal endophthalmitis in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:59-65.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, Stanford MR. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:403-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Binder MI, Chua J, Kaiser PK, Procop GW, Isada CM. Endogenous endophthalmitis: an 18-year review of culture-positive cases at a tertiary care center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:97-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Khan S, Athwal L, Zarbin M, Bhagat N. Pediatric infectious endophthalmitis: a review. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2014;51:140-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Margo CE, Mames RN, Guy JR. Endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1298-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |