Published online Aug 8, 2016. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v5.i3.244

Peer-review started: March 1, 2016

First decision: March 22, 2016

Revised: April 5, 2016

Accepted: April 21, 2016

Article in press: April 22, 2016

Published online: August 8, 2016

Processing time: 159 Days and 18.8 Hours

Osteomyelitis is a bone infection that requires prolonged antibiotic treatment and potential surgical intervention. If left untreated, acute osteomyelitis can lead to chronic osteomyelitis and overwhelming sepsis. Early treatment is necessary to prevent complications, and the standard of care is progressing to a shorter duration of intravenous (IV) antibiotics and transitioning to oral therapy for the rest of the treatment course. We systematically reviewed the current literature on pediatric patients with acute osteomyelitis to determine when and how to transition to oral antibiotics from a short IV course. Studies have shown that switching to oral after a short course (i.e., 3-7 d) of IV therapy has similar cure rates to continuing long-term IV therapy. Prolonged IV use is also associated with increased risk of complications. Parameters that help guide clinicians on making the switch include a downward trend in fever, improvement in local tenderness, and a normalization in C-reactive protein concentration. Based on the available literature, we recommend transitioning antibiotics to oral after 3-7 d of IV therapy for pediatric patients (except neonates) with acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis if there are signs of clinical improvement, and such regimen should be continued for a total antibiotic duration of four to six weeks.

Core tip: When is an appropriate time to switch to oral antibiotics is a challenging question surrounding the treatment of acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis in pediatrics. With improvements in disease management and antibiotic therapy, the standard of care is progressing to a shorter duration of intravenous antibiotics and transitioning to oral therapy for the rest of the treatment course. This review aims to evaluate the current literature in order to help clinicians make sound decisions on when and how to transition from intravenous antibiotics to oral therapy in pediatric patients with acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis.

- Citation: Batchelder N, So TY. Transitioning antimicrobials from intravenous to oral in pediatric acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis. World J Clin Pediatr 2016; 5(3): 244-250

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v5/i3/244.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i3.244

Osteomyelitis is an infection of the bone. These infections can spread to the bone numerous ways including trauma, cellulitis, septic arthritis, or bacteremia. Acute osteomyelitis in children is most commonly hematogenous in origin[1]. In high-income countries, acute osteomyelitis occurs in about 8 of 100000 children per year, but it is considerably more common in low-income countries[2]. Boys are two times more prone to acute osteomyelitis than girls[2]. While Kingella kingae is the most common causative organism of acute osteomyelitis below the age of 4 years[3], Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is the predominant pathogen in older children, followed by Streptococcus pyogenes[2,4].

Osteomyelitis can be classified into three separate categories: Acute, subacute, and chronic. Osteomyelitis is considered as acute if the duration of illness is less than two weeks; subacute, if the duration is two weeks to three months; and chronic, if the duration is longer than three months[5]. Clinical manifestations of osteomyelitis can vary depending on the location of the infected bone, but since the majority of osteomyelitis in children affects the bones of the legs, a classic sign is limping or an inability to walk[6]. Other symptoms include fever, focal tenderness, visible redness, or swelling around the infected area[6]. If physical examination suggests bone involvement, then further studies are necessary. Radiograph can show signs of osteomyelitis two to three weeks after symptom onset so an early negative radiograph cannot rule out acute osteomyelitis[6]. Magnetic resonance imaging remains the most useful imaging method for diagnosing osteomyelitis, but it presents other problems such as an increase in cost and the potential requirement of sedation in pediatric patients[6].

Elevations in C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) also have high sensitivities for diagnosis[6]. Both CRP and ESR are strong markers of systemic inflammation in the body, but CRP has a much shorter half-life which makes it more useful in acute osteomyelitis[6,7]. A CRP level of 2 mg/dL and above has been found to be sensitive in the diagnosis of osteomyelitis, and this level tends to descend quickly during the early treatment phase if the proper antibiotic is used[7].

The role of surgery in pediatric patients with acute osteomyelitis is not well understood because of the lack of randomized trials regarding this subject. Questions remain about the overall need for surgical intervention other than biopsy to diagnose osteomyelitis and help guide antimicrobial treatment. Conservative treatment is effective up to 90% of the time in acute osteomyelitis if it is diagnosed early in the course of illness[8,9]. Therefore, the general recommendation for acute osteomyelitis requires a prolonged course of antibiotics. In the past, four to six weeks of antibiotic therapy delivered through the intravenous (IV) route was the standard of care and often required the placement of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) for medication administration. PICC’s are effective for delivering high concentrations of antibiotics for serious infections but have several downfalls including the risk of developing other infections, thrombotic events, and mechanical complications[10]. Because of these potential problems, many clinicians have started looking into transitioning to oral antibiotics sooner. This review aims to evaluate the current literature in order to help clinicians make sound decisions on when and how to transition from IV antibiotics to oral therapy in pediatric patients with acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis, defined as osteomyelitis without any open wounds, fractures or adjacent joint infection and with clinical symptoms of less than 2 wk[11].

MEDLINE/PubMed searches were performed by the investigators to identify all literature published over the past two decades since 1996 that addressed antibiotic management for osteomyelitis in pediatric patients. The searches were done on PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). One set was created using the Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms “pediatric” OR “children”, “osteomyelitis”, “antibiotic”, “intravenous”, and “oral”. Combining the five sets with the Boolean “AND” function yielded 61 citations. We included article types consisting of only clinical trials, journal articles, reviews, and systematic reviews. We limited our search to articles that had full text and excluded abstracts only, case reports, incomplete reports, and letters from our review.

One of the first studies that evaluated early transition of antibiotics to oral therapy in pediatric patients with acute osteomyelitis was by Peltola et al[12] in 1997. This was a prospective study with the purpose of simplifying treatment of confirmed acute staphylococcal osteomyelitis in fifty children between the ages of three months and fourteen years[12]. The majority of patients were diagnosed with plain osteomyelitis without adjacent joint infection. Sixty-two percent of the patients underwent no surgery or only needle aspiration as a diagnostic tool during the treatment period[12]. Patients received either 37.5 mg/kg every 6 h of cephradine or clindamycin at 10 mg/kg every 6 h intravenously. This cohort had an average baseline CRP level of around 7 mg/dL which continued to rise on the first couple of days and then started to decline after the antibiotic had started clearing the infection[12]. After three to four days of therapy, the antibiotic was switched to oral for a total treatment duration of three to four weeks[12]. These children had an average hospitalization of eleven days, and their CRP (i.e., < 2 mg/dL) and ESR (i.e., < 20 mm/h) normalized within nine days and twenty-nine days, respectively[12]. The results showed that early transition to oral antibiotics within four days did not cause any treatment failure or long-term sequelae in this cohort of pediatric patients with acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis[12]. This study was one of the first looking at a short duration of IV antibiotics and was able to assess several outcomes, but the results might be limited by its small sample size.

Another prospective, randomized study on the treatment of acute osteomyelitis in pediatric patients was performed in 2010[13]. One hundred and thirty-one children aged three months to fifteen years were randomized to receive either two to four days of IV treatment followed by oral antibiotics for either twenty or thirty days[13]. The majority of the diagnosed osteomyelitis pertained to the long bones of the lower extremity that were caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA)[13]. Dosing of antibiotics used were clindamycin 40 mg/kg per day divided into four doses or cephradine 150 mg/kg per day divided into four doses[13]. Majority of the children went through diagnostic aspiration; only 24% of the patients did not undergo any surgery[13]. The primary outcome was the comparison of full recovery from acute osteomyelitis between the 20-d and 30-d groups[13]. CRP levels were monitored and showed an elevation on the first two days of treatment with an average baseline of 9.9 mg/dL, but this inflammatory marker began to trend down as the antibiotic course progressed with the majority of CRP levels being less than 2 mg/dL by day nine[13]. The data of this study showed excellent results for both groups, and they found that there were not any significant radiological, hematological, or clinical differences between the groups[13]. The authors concluded that a shorter 20-d course of antibiotics with only two to four days of IV therapy are enough for the treatment of acute osteomyelitis if the child is clinically improving and the CRP has gone down to below 2 mg/dL within seven to ten days[13]. A strength of this study is its design giving it valuable internal validity, but some children received other antibiotic in addition to the recommended agents and the treatment duration was not always the exact twenty or thirty days.

A study by Arnold et al[14] specifically looked at CRP levels as a marker to help clinicians decide on when to step down to oral therapy for acute bacterial osteo-articular infections. This study consisted of a primary chart review of 194 children from one month to eighteen years old with either acute bacterial arthritis (n = 32), acute bacterial osteomyelitis (n = 113), or both (n = 49)[14]. Surgical intervention was not discussed in this study. These subjects’ CRP averaged at 9.1 ± 7.4 mg/dL on admission and 2.0 ± 1.8 mg/dL when the patients were transitioned to oral antibiotics[14]. The mean duration of IV therapy was 1.7 wk and the mean duration of total antibiotic course was 7.1 wk[14]. The most common organism causing the infection was MSSA[14]. Out of the 194 patients, all but one were successfully treated with step-down oral therapy after having clinical improvement and an elevated CRP that had decreased below 3 mg/dL[14]. The child who failed therapy was thought to have had a fragment of infected bone in the joint space that was not removed at the time of initial surgical debridement[14]. This study was able to maintain the sequence of events as a retrospective study, but capturing the information from a chart review might have led to limitations regarding data collection.

A systematic review from 2002 evaluated the appropriate duration of IV antibiotics for acute hematogenous osteomyelitis due primarily to S. aureus in children aged three months to sixteen years[10]. Two hundred and thirty children were included in this review that compared clinical cure rates at six months in patients who received seven days or less of IV therapy to those who received greater than one week of IV therapy[10]. Thirty to around ninety percent of the patients underwent surgical intervention. In most cases, it was not stated whether these procedures were for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. The patients’ CRP levels were not reported in this study. No significant difference was observed between the groups in regards to the total duration of antibiotic treatment[10]. The cure rates between the groups were statistically insignificant (P = 0.224) as the cure rate for the shorter IV therapy group was 95.2% (95%CI: 90.4-97.7) and the other group had a cure rate of 98.8% (95%CI: 93.6-99.8)[10]. The authors of this systematic review concluded that the efficacy is similar between a short and long course of IV antibiotics for the treatment of acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis in pediatric patients, and it is appropriate to switch to oral for the rest of the treatment course after seven days of IV antibiotics[10]. This systematic review had a good sample size, but it only looked at cohort studies and did not include results from any randomized controlled trials.

Since that time, more trials and reviews had shown similar results in that a short course of IV antibiotics with a transition to oral therapy did not show any differences in clinical outcomes compared to long courses of IV antibiotics even when the short course of IV therapy was given for less than one week[15-18]. For example, a prospective, bi-center study collected data on seventy consecutive children aged two weeks to fourteen years[15]. These children did not have any underlying disease or medical condition predisposing them to infection[15]. All of the cases were found to be from S. aureus and the median duration of hospital stay was five days[15]. Surgical intervention was not discussed in this study. The outcomes showed that 59% of children were converted to oral therapy after three days and 86% after five days of IV antibiotics[15]. This study revealed that a prolonged fever (i.e., > 3-5 d) and an elevated initial CRP (i.e., > 10 mg/dL) resulted in patients requiring longer IV treatment probably because the clinicians did not want to switch to oral agents when there were persistent elevations in the inflammatory markers[15]. This study demonstrated that in otherwise healthy patients, three weeks of total antibiotic therapy should be appropriate if the patients have already finished five days or less of IV treatment[15]. The authors also concluded that temperature and CRP were the best quantitative measurements for monitoring and assessing patients’ response to therapy[15].

Another large retrospective study was performed by Zaoutis et al[19] that aimed to compare the treatment failure rate between patients two months to seventeen years old (n = 1969) discharged with IV and oral antibiotics. One thousand and twenty-one patients had a central venous catheter placed for long-term IV therapy and 948 patients received oral therapy at discharge[19]. The two groups were virtually identical in terms of demographic characteristics, which included 37% of the subjects in the IV therapy group and 33% in the oral therapy group who had undergone a surgical procedure for diagnostic or treatment purposes[19]. The median length of stay in the hospital prior to discharge was five days for the IV group and four days for the oral group[19]. The primary outcome of the study was treatment failure defined as re-hospitalization within six months with an assigned diagnosis or procedure code consistent with osteomyelitis[19]. The treatment failure was 5% in the prolonged IV group and 4% in the oral group (OR = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.49-1.22)[19]. The authors concluded that early transition to oral therapy did not increase the risk of treatment failure[19]. A limitation of this large retrospective study is the possibility that some patients might have been admitted to other hospitals not included in this study for treatment failure or complications.

Similarly, a systematic review in 2013 assessed a primary outcome of cure rates in protracted treatment compared to a shorter duration of antibiotic therapy[18]. The results stemmed from six randomized controlled trials and twenty-eight observational studies[18]. Most of the studies included did not mention the use of surgical procedures for treatment, except for one randomized controlled trial that included 12 children who went through surgical drainage. The majority of the randomized controlled trials focused on the choice of antibiotic or total duration of treatment[18]. The bulk of the observational studies addressed the duration of IV treatment and were split into two groups: Short duration which consisted of all studies that had less than seven days of IV antibiotic therapy and long duration which included all studies that had seven days or greater of IV antibiotic therapy[18]. The success rate of the short-duration group ranged from 77%-100% and that of the long-duration group ranged from 80%-100%[18]. This 2013 review concluded that acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis in children greater than three months old can be treated with three to four days of IV antibiotics and be transitioned to oral if the child is clinically improving[18]. The authors classified the strength of their recommendations as weak because the review was derived from observational studies and a small number of randomized controlled trials with important limitations in regards to lack of blinding, small sample size, or a prolonged recruitment period.

A recent retrospective study published in 2015 evaluated the clinical outcome of 2060 children who were either discharged with IV or oral antibiotic[1]. The majority of patients were male, aged five to thirteen years, Caucasians, and had osteomyelitis of the leg, foot, or ankle. One thousand and five children received oral antibiotics at discharge and the remaining 1055 children received antibiotics via a PICC line[1]. The baseline characteristics showed that 17.1%, 39%, 13.5%, and 16.7% of participants underwent arthrocentesis, osteotomy, incision and drainage, and arthrotomy, respectively[1]. This study did not report on the participants’ CRP levels. The median length of stay in the hospital was six days for both groups before being discharged with either an oral or IV antibiotic[1]. This study showed that treatment failure was 5% in patients discharged with oral antibiotic therapy and 6% in the group who received antibiotics through a PICC at discharge with no statistical significance (P = 0.77)[1]. A high frequency of PICC-related adverse outcomes requiring ED visits or re-hospitalization was observed in the IV group compared to the oral group[1]. Despite of the limited data on treating young children less than five years of age with oral therapy, this large retrospective study showed that there was not any clinically relevant difference in treatment efficacy between IV and oral therapy in this age group[1]. This study also looked to see if the isolation of MRSA as the cause of osteomyelitis had an impact on the effect of the treatment route, but the results did not show any difference either[1].

Dartnell et al[7] performed the largest systematic review on this controversy to date which included over 12000 cases of pediatric patients with acute osteomyelitis. The majority of patients presented with acute osteomyelitis of the lower extremity and initially had localized pain and fever[7]. This systematic review discussed the role of surgery, but it did not mention the overall percentage of patients in the cohort who had such intervention[7]. The initial average CRP level was elevated at 8.5 mg/dL and resulted in a peak level around day two of treatment[7]. Twelve of the included studies were described as prospective, but there was only one randomized controlled study which made statistical analysis of all these studies combined not achievable[7]. This review concluded that short-term parenteral medication is acceptable in cases of osteomyelitis when the patients do not show any signs of complications and exhibit clinical improvement and normalization of hematological markers within the first few days of IV therapy provided that the oral antibiotic is effective, the microorganism isolated is susceptible to the administered drug, and the correct dose is used[7]. The authors also added that there is an increasing evidence that long-term IV therapy can do more harm than good and can lead to complications that may arise from extended IV treatment[7]. This systematic review did include some reports from developing countries which provided useful information, but it might lack external validity when trying to extrapolate the data to developed countries.

There is an ongoing study by Grimbly et al[2] that aims to evaluate the literature looking for evidence to support the optimal duration of treatment for both parenteral and oral therapy when managing acute osteomyelitis in children less than eighteen years of age[2]. The authors will conduct a comprehensive review of approximately 3400 studies; these studies will be limited to randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials found through multiple database searches that compare an IV antibiotic course of less than seven days to that greater than seven days[2]. Studies included will describe the antibiotics used as well as the route and duration for at least a three-month timespan[2]. The primary outcome of this study will be the success of the treatment options by the end of therapy defined by resolution of symptoms which include pain, local tenderness, swelling, and gait abnormalities[2]. One of the secondary outcomes will be looking at surgical intervention. The results of this study will surely add to the strength of the current evidence for the early transition of antibiotics to oral in pediatric patients with acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis. Table 1 summarizes all the aforementioned studies.

| Ref. | Study type | Population | Objective | Results | Conclusion |

| Peltola et al[12] | Prospective | 50 children (3 mo to 14 yr) | Determined the full recovery rate and remaining health of patients transitioned to oral antibiotics at 12 mo from hospital discharge | 100% had full recovery | Treatment of pediatric osteomyelitis can be simplified and costs reduced by switching to oral early on in the treatment course |

| Le Saux et al[10] | Systematic review (12 prospective studies) | 230 children (3 mo to 16 yr) | Compared the cure rates at 6 mo for IV therapy ≤ 7 d and > 7 d | 95.2% - ≤ 7 d (P = 0.224) 98.8% - > 7 d (P = 0.248) | Similar cure rates between groups Increased morbidity and cost associated with long-term IV therapy |

| Prado et al[17] | Retrospective | 70 children (< 15 yr) | Assessed the efficacy of the transition to oral antibiotic after 7 d of IV therapy | No child had a complication from treatment | Seven days of an IV antibiotic for the initial treatment phase of acute osteomyelitis was effective in the majority of children |

| Zaoutis et al[19] | Retrospective cohort | 1969 children (2 mo to 17 yr) | Compared the treatment failure rate between patients discharged with IV and oral antibiotics | 5% - IV group 4% - Oral group OR = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.49-1.22 | Early transition to oral therapy did not increase the risk of treatment failure |

| Jagodzinski et al[15] | Prospective cohort | 70 children ( ≤ 16 yr) | Determined the parameters for prolonged IV antibiotic therapy of > 6 d | Fever > 38.4 °C for 3 to 5 d Admission CRP > 10 mg/dL | 3-5 d of IV antibiotic therapy followed by oral therapy for 3 wk is sufficient for uncomplicated osteoarticular infections |

| Peltola et al[13] | Prospective randomized | 131 children (3 mo to 15 yr) | Compared 20-d vs 30-d treatment with IV therapy for the first 2-4 d | 98.5% had full recovery | Most childhood osteomyelitis can be treated for a total antibiotic course of 20 d with only 2-4 d of IV therapy |

| Dartnell et al[7] | Comprehensive systematic review (132 studies) | > 12000 children (< 18 yr) | Reviewed the different features of osteomyelitis to formulate a recommendation on treatment | Short course of IV therapy is acceptable | Clinical improvements of tenderness, normal temperature, and normalized CRP (< 2 mg/dL) are good indicators for converting IV antibiotics to oral1 |

| Arnold et al[14] | Chart review | 194 children (1 mo to 18 yr) | Evaluated if CRP is a good marker to use for transitioning therapy to oral | 99.5% success rate | CRP (i.e., < 3 mg/dL) is a useful tool along with other clinical findings to help transition to oral therapy |

| Liu et al[16] | Retrospective | 95 children ( ≤ 17 yr) | Compared recurrence rates of osteomyelitis at discharge with IV or oral therapy | 0% - Oral 9% - Intravenous (P = 0.59) | Early transition to oral antibiotics may offer similar recurrence rates of osteomyelitis |

| Howard-Jones et al[18] | Systematic review (28 observational and 6 randomized) | Approximately 3000 children (< 18 yr) | Compared cure rates between shorter and longer durations of IV therapy | 77%-100% - Short duration 80%-100% - Long duration | Early transition to oral therapy after 3-4 d of intravenous therapy is as effective as longer courses1 |

| Keren et al[1] | Retrospective cohort | 2060 children (2 mo to 18 yr) | Compared therapy failure between PICC administered antibiotics and oral antibiotics | 5% - Oral route 6% - PICC route OR = 1.06, 95%CI: 0.70-1.61 | No advantage of antibiotics via PICC line Increased complications with PICC line |

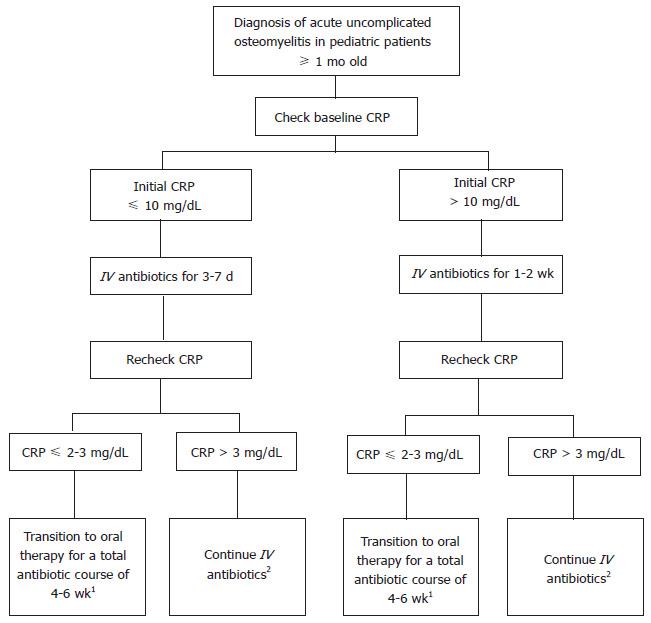

After reviewing the available literature, we recommend managing pediatric patients with acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis initially with IV antibiotics. Their fever curve, site tenderness, clinical status, and CRP level should be closely monitored. If there are improvements in these infection markers, the IV therapy can then be transitioned to oral because the latter has been shown to be just as efficacious as IV therapy in treating acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis. A baseline CRP level should be obtained in the patients before starting an antibiotic. After the first several days (i.e., 3-7 d) of IV therapy, we suggest rechecking a CRP level; and if the CRP level is less than 2-3 mg/dL, the clinicians can then consider transitioning to oral antibiotics (Figure 1). However, if the CRP is still above 2-3 mg/dL at that time, IV antibiotics should be continued and the CRP can be rechecked in a few more days. If the CRP level continues to increase from baseline by the fourth day of treatment, then this should alert the clinician that the patients may have developed some complications from the infection and thus may require thorough re-evaluation, a longer course of IV antibiotic, and/or a surgical intervention[10].

Some patients, however, may not be good candidates for switching over to oral antibiotics after a short IV course. If the child has fevers persisting for more than three to five days after starting treatment, then IV antibiotics should be continued for a longer course. Also, if the initial CRP is above 10 mg/dL, which usually correlates to a more severe and potentially complicated osteomyelitis, a longer duration of IV therapy may be necessary[7,15]. This clinical practice has not been studied in neonates with acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis; as a result, this population should continue receiving a longer-term of IV antibiotics to ensure that the infection is treated properly. Besides neonates, patients with complicated osteomyelitis such as bone fracture, bacteremia, abscess, growth arrest, or chronic infection also should not transition to oral therapy early. Patients with other comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus, sickle-cell disease, or children who are immunocompromised should consider receiving a longer course of IV antibiotics due to their clinical condition pre-disposing them to a more serious infection. Finally, patients who have a history of osteomyelitis or recent treatment failure for acute osteomyelitis should also consider a longer duration of IV therapy until studies are performed to evaluate the appropriateness of early transition of antibiotics to oral in this population.

Several practical advantages of a shorter course of IV antibiotic exist, and they include a shorter hospital stay, decreased morbidity from IV lines, and more cost effectiveness[12]. A common issue causing longer hospital stay is that the patients continue to have an IV line in place preventing discharge. Transitioning to oral therapy when clinically ready will help shorten hospitalization. Switching to oral therapy can also decrease the risk of complications related to long-term IV antibiotic administration. Most complications from IV lines are not serious, but they do result in significant increase in emergency department or clinic visits, or even hospital readmissions[14]. These complications, as a result, can increase cost burden for the healthcare system. Considering the cost of IV antibiotic treatment vs oral, there is a huge difference between the two[5]. In summary, since there are not any clinical differences observed in the early transition to oral antibiotics, clinicians can surely consider such practice in their pediatric patients with acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis.

Clinicians should consider transitioning antibiotic from IV to oral in pediatric patients with acute osteomyelitis when there is a downward trend in their fever curve, improved tenderness in the affected area, a reduction in CRP, and overall clinical improvement. These recommendations only pertain to patients with acute uncomplicated osteomyelitis that are responding well to early IV treatment. Questions relating to this clinical practice that still need to be answered include the appropriateness of such early transition in neonates and if specific organisms direct such transitions from IV to oral therapy.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Bose D, Deng B, Yagupsky PV S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Keren R, Shah SS, Srivastava R, Rangel S, Bendel-Stenzel M, Harik N, Hartley J, Lopez M, Seguias L, Tieder J. Comparative effectiveness of intravenous vs oral antibiotics for postdischarge treatment of acute osteomyelitis in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:120-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Grimbly C, Odenbach J, Vandermeer B, Forgie S, Curtis S. Parenteral and oral antibiotic duration for treatment of pediatric osteomyelitis: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2013;2:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chometon S, Benito Y, Chaker M, Boisset S, Ploton C, Bérard J, Vandenesch F, Freydiere AM. Specific real-time polymerase chain reaction places Kingella kingae as the most common cause of osteoarticular infections in young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jaberi FM, Shahcheraghi GH, Ahadzadeh M. Short-term intravenous antibiotic treatment of acute hematogenous bone and joint infection in children: a prospective randomized trial. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:317-320. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Krogstad P, Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL. Osteomyelitis. Pediatric infectious diseases. Philadelphia: Saunders 2009; 725-742. |

| 6. | Peltola H, Pääkkönen M. Acute osteomyelitis in children. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:352-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dartnell J, Ramachandran M, Katchburian M. Haematogenous acute and subacute paediatric osteomyelitis: a systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:584-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vaughan PA, Newman NM, Rosman MA. Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1987;7:652-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cole WG, Dalziel RE, Leitl S. Treatment of acute osteomyelitis in childhood. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64:218-223. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Le Saux N, Howard A, Barrowman NJ, Gaboury I, Sampson M, Moher D. Shorter courses of parenteral antibiotic therapy do not appear to influence response rates for children with acute hematogenous osteomyelitis: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2002;2:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bachur R, Pagon Z. Success of short-course parenteral antibiotic therapy for acute osteomyelitis of childhood. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2007;46:30-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Peltola H, Unkila-Kallio L, Kallio MJ. Simplified treatment of acute staphylococcal osteomyelitis of childhood. The Finnish Study Group. Pediatrics. 1997;99:846-850. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Peltola H, Pääkkönen M, Kallio P, Kallio MJ. Short- versus long-term antimicrobial treatment for acute hematogenous osteomyelitis of childhood: prospective, randomized trial on 131 culture-positive cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:1123-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arnold JC, Cannavino CR, Ross MK, Westley B, Miller TC, Riffenburgh RH, Bradley J. Acute bacterial osteoarticular infections: eight-year analysis of C-reactive protein for oral step-down therapy. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e821-e828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jagodzinski NA, Kanwar R, Graham K, Bache CE. Prospective evaluation of a shortened regimen of treatment for acute osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:518-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu RW, Abaza H, Mehta P, Bauer J, Cooperman DR, Gilmore A. Intravenous versus oral outpatient antibiotic therapy for pediatric acute osteomyelitis. Iowa Orthop J. 2013;33:208-212. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Prado S MA, Lizama C M, Peña D A, Valenzuela M C, Viviani S T. Short duration of initial intravenous treatment in 70 pediatric patients with osteoarticular infections. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2008;25:30-36. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Howard-Jones AR, Isaacs D. Systematic review of duration and choice of systemic antibiotic therapy for acute haematogenous bacterial osteomyelitis in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:760-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zaoutis T, Localio AR, Leckerman K, Saddlemire S, Bertoch D, Keren R. Prolonged intravenous therapy versus early transition to oral antimicrobial therapy for acute osteomyelitis in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:636-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |