Published online May 8, 2016. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v5.i2.206

Peer-review started: August 28, 2015

First decision: December 4, 2015

Revised: January 9, 2016

Accepted: January 29, 2016

Article in press: January 31, 2016

Published online: May 8, 2016

Processing time: 109 Days and 16.8 Hours

AIM: To review empirical evidence on character development among youth with chronic illnesses.

METHODS: A systematic literature review was conducted using PubMed and PSYCHINFO from inception until November 2013 to find quantitative studies that measured character strengths among youth with chronic illnesses. Inclusion criteria were limited to English language studies examining constructs of character development among adolescents or young adults aged 13-24 years with a childhood-onset chronic medical condition. A librarian at Duke University Medical Center Library assisted with the development of the mesh search term. Two researchers independently reviewed relevant titles (n = 549), then abstracts (n = 45), and finally manuscripts (n = 3).

RESULTS: There is a lack of empirical research on character development and childhood-onset chronic medical conditions. Three studies were identified that used different measures of character based on moral themes. One study examined moral reasoning among deaf adolescents using Kohlberg’s Moral Judgement Instrument; another, investigated moral values of adolescent cancer survivors with the Values In Action Classification of Strengths. A third study evaluated moral behavior among young adult survivors of burn injury utilizing the Tennessee Self-Concept, 2nd edition. The studies observed that youth with chronic conditions reasoned at less advanced stages and had a lower moral self-concept compared to referent populations, but that they did differ on character virtues and strengths when matched with healthy peers for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Yet, generalizations could not be drawn regarding character development of youth with chronic medical conditions because the studies were too divergent from each other and biased from study design limitations.

CONCLUSION: Future empirical studies should learn from the strengths and weaknesses of the existing literature on character development among youth with chronic medical conditions.

Core tip: This study reviewed empirical evidence on character development among youth with chronic medical conditions. Only three quantitative studies were found that met the review inclusion criteria. Different measures of character were evaluated including moral reasoning, moral concept, and character virtues. Collectively, the findings were not generalizable and were too divergent to support or contradict each other. The strengths and weaknesses of the emerging literature offer insights into how best to design future studies on character development among youth with chronic illnesses.

- Citation: Maslow GR, Hill SN. Systematic review of character development and childhood chronic illness. World J Clin Pediatr 2016; 5(2): 206-211

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v5/i2/206.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v5.i2.206

As more and more adolescents with chronic illness survive into adulthood it is vital that we understand how best to support their development into thriving adults. The study of chronic illness in adolescence has been approached from many aspects of development including social development, emotional development, and cognitive development[1,2]. Yet, little is known about the Positive Youth Development (PYD) of these youth which focuses on the development of strengths in adolescence that is associated with positive outcomes[3].

PYD, as described by Richard M Lerner, PhD, is a model that has been validated using a global measure and sub-constructs consisting of Five C’s: Character, caring, connectedness, competence, and confidence (Table 1)[4,5]. All six factors are stable measures across developmental stages from childhood to adulthood and are modifiable based on experiences and environmental resources[6-8]. Youth with higher scores for PYD and the Five C’s have higher contribution to society and lower rates of problem behaviors and depression[6]. Accordingly, many youth programs that have been designed to improve outcomes target character development defined by personal standards, moral behavior, or personal strengths (e.g., diligence)[9,10].

| PYD five C’s | Definitions |

| Competence | Positive view of one’s actions in domain specific areas including social, academic, cognitive, and vocational. Social competence pertains to interpersonal skills (e.g., conflict resolution). Cognitive competence pertains to cognitive abilities (e.g., decision making). School grades, attendance, and test scores are part of academic competence. Vocational competence involves work habits and career choice explorations |

| Confidence connection | An internal sense of overall positive self-worth and self-efficacy; one’s global self-regard, as opposed to domain specific beliefs. Positive bonds with people and institutions that are reflected in bidirectional exchanges between the individual and peers, family, school, and community in which both parties contribute to the relationship |

| Character | Respect for societal and cultural rules, possession of standards for correct behaviors, a sense of right and wrong (morality), and integrity |

| Caring and compassion | A sense of sympathy and empathy for others |

For youth with chronic illnesses, a strong character is commonly acknowledged as an essential trait given the persistent health challenges they face[7,8]. Anecdotally there are many stories which attest to the strength of children living with chronic medical conditions. To quote one such newspaper article describing a 15 years old with cancer: “(She) has been a symbol of courage and strength for those who know her[11].” Similar sentiments and accounts of character growth due to the illness experience were noted in qualitative interviews that we conducted of adolescents with chronic conditions and their parents (unpublished data).

However, rigorous empirical research on character development among adolescents with chronic illnesses is in a nascent state. Key questions remain as to whether or not character development is different for youth with chronic medical conditions and what specific attributes of character should be targeted for interventions. To answer these inquiries, there are a variety of theoretical frameworks, research study designs, methods (i.e., measures and approaches), and statistical techniques that can be used. Also, the influence of the disease state-type, onset, severity, and prognosis - must be taken into consideration. In addition, thought has to be given to the developmental stage of interest to select the most appropriate evaluation. Given the complexity, emerging quantitative research on this topic has the potential to be varied and divergent.

Accordingly, the aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of studies investigating character development among adolescents and young adults with chronic medical conditions. Our objectives were to synthesize the existing empirical research and provide recommendations for future directions. We sought to find quantitative research that measured character, moral development, or moral behavior to be consistent with Lerner’s PYD definition[4]. To identify character traits across different diseases, we utilized a non-categorical approach for childhood chronic illnesses.

The mesh search term was created by a librarian at Duke University Medical Center Library, combining words related to character development, chronic conditions, and childhood.

Character development: Positive youth development, character development, personality development, altruism, character, empathy, integrity, conscientiousness, courage, social values, virtues, emotional maturity, loyalty, moral, open-mindedness, sincerity

Chronic conditions: Diabetes, cancer, epilepsy, seizures, neoplasms, inflammatory bowel disease, crohns disease, ulcerative colitis, asthma, burns, headaches, cerebral palsy, deafness, blindness, hemophilia, celiac disease, migraine disorders, HIV, neurofibromatosis, sickle cell disease, anemia, obesity, congenital heart disease, cystic fibrosis, spina bifida, hemophilia, muscular dystrophy, chronic illness, chronic disease.

Childhood: Pediatric, adolescent, adolescence, teen, teenager, child, youth.

The contents of the PubMed and PSYCHINFO databases were searched from inception through November 2013. References of relevant publications were also reviewed to identify additional titles. The searches were limited to English language publications with participants 13-24 years of age. The full search strategy is available from the corresponding author.

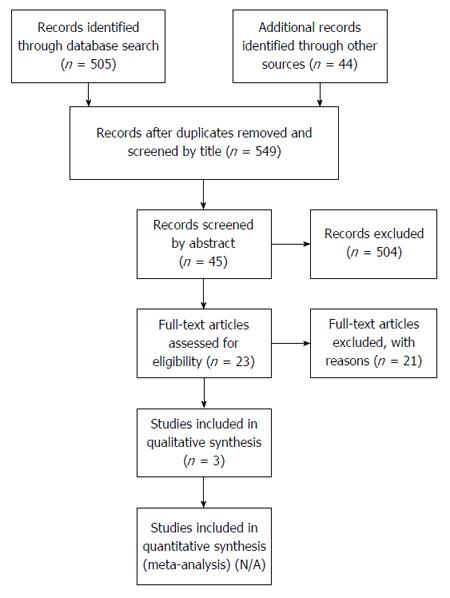

Two reviewers independently reviewed all titles produced by the initial searches (n = 549) and excluded those that were definitively irrelevant to the search intent. Any titles which were insufficiently clear to make such a determination were retained for review at the abstract level. All of the remaining abstracts (n = 45) were then independently screened for the following inclusion criteria: (1) population of children or adolescents up to 21 years of age with a chronic condition; and (2) examined some aspect of character development. Those meeting the criteria were included in the study. Figure 1 provides a PRISMA flowchart depicting the number of publications included and excluded at each stage of review[12]. Biostatistics were not used for sampling purposes, summarization of the data, analysis, interpretation, or inference. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Sherika N Hill, PhD from Duke University and deemed appropriate for a systematic literature review.

Three studies were identified that met inclusion criteria and examined character development among participants with childhood-onset chronic conditions[13-15]. Two studies found lower scores indicative of character deficiencies for individuals with chronic conditions compared to normative samples while one study found adolescents with a chronic condition to be similar in character to healthy peers matched by age and sex[13-15]. All of the studies were prospective, observational, cross-sectional, survey-based, and informed by self-report. However, they differed in their designs (type of comparison group), methods (samples, recruitment, measures, survey administration), and analyses (statistical approaches).

The study findings are summarized in Table 2. The first study by Sam and Wright[15] (1988) examined moral reasoning among 15 deaf adolescents as compared to population norms using modified versions of dilemmas from Kohlberg’s Moral Judgment Instrument. Deaf adolescents’ moral reasoning was more basic (Stage 1 and 2 of the Pre-conventional Level) compared to advanced stages of reasoning (Stages 2, 3 or 4 of Conventional Level) of the referent group[15]. In the second study, Guse and Eracleous[13] (2011) compared responses to the Values in Action Inventory Classification of Character Strengths for Youth of 21 adolescent cancer survivors to healthy peers matched on age, sex and race/ethnicity[13]. There was no difference in scores between groups on the 5 character virtues and 15 character strengths tested. Russell et al[14] (2013) conducted a third study that examined moral self-concept among 82 young adults who were burn survivors from childhood using the Tennessee Self-Concept Scale 2nd edition. The burn survivors had a significantly lower score (P = 0.036) on the Moral Sub-scale compared to a reference population[14].

| Ref. | n | Subjects | Measures | Results |

| Sam et al[15] | 15 | Deaf | Kohlberg Moral Judgment Instrument | Moral reasoning for deaf participants was at a lower/basic stage of development compared to norms |

| Ages 12-15 yr | ||||

| Guse et al[13] | 42 | 21 cancer survivors | Values in Action Inventory for Youth | No difference in mean scores |

| 21 healthy peers | ||||

| Matched on age, race, and gender | ||||

| Ages 12-19 yr (mean = 16 yr) | ||||

| Russell et al[14] | 85 | Burn survivors | Tennessee Self-Concept scale - Moral subscale | Scores on moral subscale lower than norms (P = 0.036). Subscale includes moral identity, satisfaction, and behavior |

| Ages 18-30 yr (mean = 21 yr) |

The emerging research on character development among youth with chronic medical conditions is too disparate to draw conclusions. There were only three studies that met our search criteria dating back to the inception of PubMed and PSYCHINFO. Each study used a different measure of character which did not overlap in how they operationalized moral themes. Further, the social context of the study participants varied greatly from young deaf adolescents, to Australian cancer survivors, to adult burn survivors. Lastly, study design limitations such as small convenience samples further limited generalizability. Consequently, the results from the studies neither supported nor contradicted one another in advancing our understanding of character development among youth with chronic conditions.

Nonetheless, future studies can learn from the strengths and weaknesses of the emerging evidence. To operationalize character, different measures of moral development were examined. The Kohlberg Moral Judgement Instrument ranked beliefs regarding social norms while the Values In Action Classification of Strength for Youth (VIA-Youth) tallied virtues pertaining to universal constructs of goodness and the Tennessee Self-Concept (TSC) Scale scored perceived self-control[13-15].

The Kohlberg Instrument proposes that there are stages of progressive moral reasoning that ascend from an egocentric to altruistic sense of fairness[16]. A key strength of this character assessment is that moral development is presented as a continuum that can evolve as an individual ages, matures, or have critical experiences. Accordingly, the tool would be useful to track changes in moral reasoning over time. Researchers should be cautious, however, in interpreting results. For one, it is not clear if a lower, basic stage of moral reasoning represents a character deficit, developmental delay, or a lack of life experience. Secondly, critics question whether youth can fully appreciate the relationship dynamics presented in scenarios that are: (1) purely fictional in nature; and (2) have mature themes such as spousal or parental love[17]. Thirdly, scholars argue that Kohlberg’s instrument is gender-biased because the moral reasoning stages are derived from an all-male sample, resulting in lower scores for females[18]. Consequently, given that more than half of Sam and Wright subjects were female, sex differences instead of disease influences may offer a better explanation as to why deaf children had a lower stage of moral reasoning compared to instrument norms[15].

The VIA-Youth also has noteworthy merits and shortcomings to guide future research. The tool was designed to be comprehensive, gender-neutral, and cross-culturally relevant in testing universal themes of good character virtues and strengths[19]. These features make the evaluation ideal for diverse samples and questions regarding personality traits. As a trade-off, however, the self-administered survey requires keen self-awareness to accurately score 198 items and takes more than 30 min to complete. Researchers should be aware that these features could be challenging for adolescents. Case in point, one could argue that cancer survivors and healthy peers scored similarly on the VIA-Youth in the Guse and Eracleou study, selecting all mid-point responses for most items, because adolescents in general lack introspection skills as a result of their developmental stage or that respondents suffered from testing fatigue given the long, intensive survey[13,19,20].

The TSC Scale is less demanding on respondents and provides specific targets for intervention as key strengths[14]. Moral Self-Concept in the TSC is very narrowly defined as personal satisfaction with one’s self-control[14]. Accordingly, lower scores such as those reported by Russell et al[14] suggest that interventions could target either burn survivors’ personal expectations or their internal self-regulation skills. A drawback to the TSC is that the instrument is not specific to adolescents. The reference population is 13-90 years old[14].

Collectively, the three studies highlight study design issues that should be addressed in future empirical studies. For instance, the study by Sam and Wright suggests that deaf children may experience a more pervasive form of isolation because of the specialized school environment[15]. To account for disease-specific influences, future studies should seek to have a healthy comparison group as well as comparison groups of different medical conditions. Moreover, future studies should choose sampling and analytical strategies a priori that either limit or control for systematic biases introduced by weakness in the study design and methods. Although Guse and Eracleous utilized a comparison group that was matched on age, sex, and race/ethnicity, they did not address the selection bias (i.e., study subjects who selected/chose to participate in study were different from the general population) that resulted from using a convenience sampling approach[13]. Finally, future research should assess character changes within and between individuals from childhood to adulthood to identify aberrant developmental effects. In doing so, the study by Russell et al[14] would have been more informative in delineating whether the low satisfaction scores were attributable to the chronic medical condition or the challenging experience of transitioning to adulthood.

In conclusion, this literature review sets the stage for future studies of character development among adolescents with chronic illnesses. More empirical evidence is needed to inform interventions and provide a better understanding of how adversity affects character development during adolescence in general. Building character strengths broadly, and moral development specifically, is important to ensure that adolescents thrive as they transition into adulthood.

As more adolescents with chronic illness survive into adulthood, it is vital to understand how best to support their development into thriving adults; however, little is known about the Positive Youth Development (PYD) of these youth which focuses on the development of strengths in adolescence.

The study of chronic illness in adolescence has been approached from many aspects of development including social development, emotional development, and cognitive development. Given the persistent health challenges among youth with chronic illnesses, a strong character is commonly acknowledged as an essential trait among this population. However, rigorous empirical research on character development among adolescents with chronic illnesses is in a nascent state.

Collectively, the three studies included in this review highlight study design issues that should be addressed in future empirical studies. To account for disease-specific influences, future studies should seek to have a healthy comparison group as well as comparison groups of different medical conditions. Moreover, future studies should choose sampling and analytical strategies a priori that either limit or control for systematic biases introduced by weakness in the study design and methods.

Positive Youth Development - a strengths-based perspective regarding the development and positive growth of adolescents and young adults.

The author conducted a systematic review to find character strengths among youth with chronic illness, found that there was no empirical research regarding this area of study, and proposed how to design future studies on this research.

P- Reviewer: Watanabe T, Contreras CM S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Roberts MC, Steele RG. Handbook of pediatric psychology. 2010;. |

| 2. | Thompson RJ, Gustafson KE. Adaptation to chronic childhood illness. Washington, DC: American Pscyhological Association 1996; . [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Lerner RM, Lerner JV, Benson JB. Positive youth development: Processes, programs, and problematics. J Youth Dev. 2011;6:40-64. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lerner RM, Lerner JV, Almerigi JB, Theokas C, Phelps E, Gestsdottir S, Naudeau S, Jelicic H, Alberts A, Ma L. Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. J Early Adolesc. 2005;25:17-71. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Bowers EP, Li Y, Kiely MK, Brittian A, Lerner JV, Lerner RM. The Five Cs model of positive youth development: a longitudinal analysis of confirmatory factor structure and measurement invariance. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:720-735. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lerner RM, Overton WF, Molenaar PC. Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, Theory and Method. 2015;. |

| 7. | Lerner RM, von Eye A, Lerner JV, Lewin-Bizan S, Bowers EP. Special issue introduction: the meaning and measurement of thriving: a view of the issues. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:707-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lerner RM, Lerner JV, von Eye A, Bowers EP, Lewin-Bizan S. Individual and contextual bases of thriving in adolescence: a view of the issues. J Adolesc. 2011;34:1107-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Berkowitz MW, Battistich VA, Bier MC. What works in character education: What is known and what needs to be known. 2008;414-431. |

| 10. | Berkowitz MW, Bier MC. What works in character education: A research-driven guide for educators. Washington, DC: Character Education Partnership 2005; . |

| 12. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9247] [Cited by in RCA: 8866] [Article Influence: 554.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Guse T, Eracleous G. Character strengths of adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. Health SA Gesondheid. 2011;16. |

| 14. | Russell W, Robert RS, Thomas CR, Holzer CE, Blakeney P, Meyer WJ. Self-perceptions of young adults who survived severe childhood burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34:394-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sam A, Wright I. The structure of moral reasoning in hearing-impaired students. Am Ann Deaf. 1988;133:264-269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Kohlberg L. The development of children’s orientations toward a moral order. I. Sequence in the development of moral thought. Vita Hum Int Z Lebensalterforsch. 1963;6:11-33. [PubMed] |

| 17. | McLeod S. Kohlberg Stages of moral development. Simply Psychology serial online. Available from: http://www.simplypsychology.org/kohlberg.html. |

| 18. | Gilligan C. In a different voice: Women’s conceptions of self and of morality. Harvard Educational Review. 1977;47:481-517. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Peterson C, Seligman ME. The Values in Action (VIA) classification of strengths. A life worth living: Contributions to positive psychology. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press 2006; 29-48. |