Published online Aug 8, 2014. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v3.i3.54

Revised: June 16, 2014

Accepted: July 12, 2014

Published online: August 8, 2014

Processing time: 187 Days and 1.1 Hours

Cyclical vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a functional, debilitating disorder of childhood frequently leading to hospitalization. Affected children usually experience a stereotypical pattern of vomiting though it may vary between different individuals. The vomiting is intense often bilious, and accompanied by disabling nausea. Identifiable precipitating factors for CVS include psychosocial stressors, infections, lack of sleep and occasionally even food triggers. Often, it may be difficult to distinguish episodes of CVS from other causes of acute abdomen and altered consciousness. Thus, the diagnosis of CVS remains largely one of exclusion. Investigations routinely done during the work-up of a child with suspected CVS include both blood and imaging modalities. Plasma lactate, ammonia, amino acid and acylcarnitine profiles as well as urine organic acid profile are indicated to exclude inborn errors of metabolism. The treatment remains challenging and targeted at prevention or shortening of the attacks and can be considered as abortive, supportive and prophylactic. Use of non-pharmacological therapy is also part of the management of CVS. The prognosis of CVS is variable. More insight into the pathogenesis of this disorder as well as role of non-pharmacological therapy is needed.

Core tip: Cyclical vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a functional childhood disorder which has been increasingly reported in recent years. Much of its pathogenesis remains unknown. Diagnosis may be delayed if not considered by paediatricians. Management of CVS still remains a challenge.

- Citation: Tan ML, Liwanag MJ, Quak SH. Cyclical vomiting syndrome: Recognition, assessment and management. World J Clin Pediatr 2014; 3(3): 54-58

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v3/i3/54.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v3.i3.54

Cyclical vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a functional disorder in childhood which is increasingly being recognised. It is characterised by discrete episodes of recurrent profuse vomiting which are self-limiting and with periods of well-being between the attacks. Each episode is often stereotypical for the individual, in terms of onset, duration and symptoms but may vary between different individuals. The vomiting can be profuse, with bilious content occurring in most cases, and associated with extreme nausea and lethargy. Each attack can be debilitating as the child often spends days being hospitalised for intravenous hydration. Several guidelines have been written in recent years to clarify the diagnostic process of CVS and rule out other conditions that may have similar presentation.

The pathogenesis of CVS remains unknown but there appears to be a link between CVS and migraine, suggestive of a central aetiology. There are similarities in the symptoms for both conditions (e.g., nausea, photophobia, and headache) as well as some similarities in triggering factors (e.g., stress, lack of sleep). Interestingly, there is often co-existing personal or family history of migraine in individuals with CVS[1-3]. One possible explanation is that of maternal inheritance of CVS and mitochondrial DNA mutations causing deficits in cellular energy production[4]. Personal history of motion sickness has also been seen in cases of CVS.

In recent years, there have been increasing reports of cases of CVS worldwide. However, the true prevalence and incidence of CVS is difficult to establish as it often remains undiagnosed after the onset of symptoms.

Population based studies in school aged children done in Western Australia[5] and Scotland[6] showed prevalence rates of 2.3% and 1.9%, respectively. Similarly, Ertekin et al[7] reports a 1.9% prevalence rate in a cohort of school aged Turkish children. Reported incidence rates range from 1.7% to 2.7% of school aged children[6,8]. In Ireland, an incidence of 3.15 per 100000 children per annum was reported in 2005[9].

The classic patient with CVS is female (slight female predominance with female to male ratio of 1.3:1)[10], who presents with vomiting in childhood. Affected children usually experience a stereotypical pattern of vomiting classically with a consistent time of onset, duration and symptoms. The vomiting is intense (median 6 times/h at peak), often bilious (83% in some series), and accompanied by disabling nausea[11].

CVS classically has four phases: inter-episodic, prodromal, vomiting, and recovery. Recognition of this phasic pattern helps in making the diagnosis and in management. The inter-episodic phase is usually symptom free. The patient senses the approach of an episode during the prodromal phase, but is still able to take and retain oral medications. The vomiting phase is characterized by severe nausea, vomiting, retching, and other symptoms. The recovery phase begins when nausea remits and ends when the patient has recovered appetite, strength, and body weight lost during the vomiting phase.

Identifiable precipitating factors for CVS include psychosocial stressors, infections, lack of sleep and occasionally even food triggers. The resulting dehydration necessitates intravenous hydration. Often, accompanying symptoms such as pallor, listlessness, anorexia, nausea, retching, abdominal pain, headache, and photophobia may make it difficult to distinguish episodes of CVS from other causes of acute abdomen and altered consciousness.

CVS has been reported to occur in all age groups. The median age at onset of symptoms ranges from 5.2 to 6.9 years[11] although children as young as 6 mo have been described to have CVS.

Often times, in areas where the diagnosis of CVS is not well-known, many patients may spend months over repeated hospital admissions before a diagnosis is made. Patients are often misdiagnosed as food poisoning, gastro-esophageal reflux disease or peptic ulcer disease.

The diagnosis of CVS remains largely one of exclusion. In a child with recurrent vomiting, it is important to rule out life-threatening conditions such as gastro-intestinal structural anomalies including malrotation with volvulus, brain tumours and inborn errors of metabolism. Children with epilepsy can occasionally present with recurrent vomiting, especially if it involves the occipital lobe. The overall lower frequency of attacks and the higher peak intensity of vomiting in CVS usually allow its distinction from disorders such as bulimia nervosa[12]. While CVS can occur in infants and young children, a diagnosis should be made after a period of observation and careful exclusion of other causes of recurrent vomiting[13].

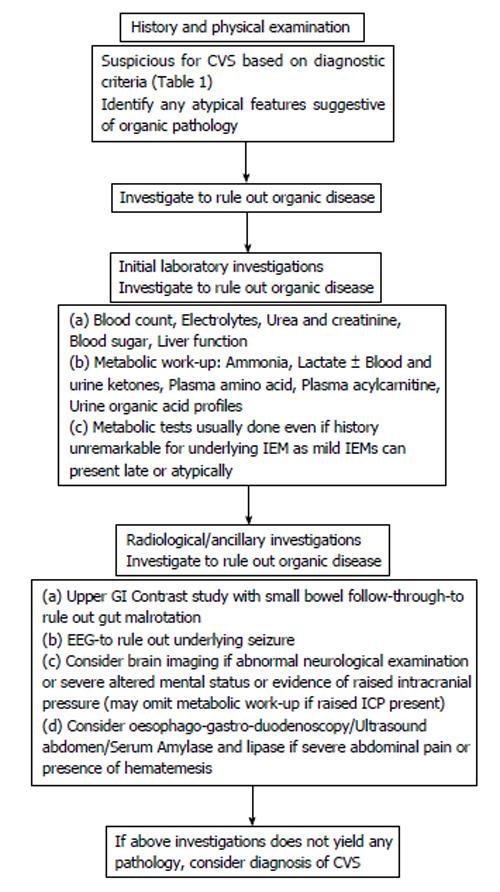

In 2008, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition appointed a task force to develop a consensus report for CVS to improve the recognition and treatment of this disorder. Table 1 shows the criteria for the diagnosis of CVS based on clinical symptoms[14]. Investigations that are routinely done during the work-up of a child with suspected CVS include both blood and imaging modalities. Figure 1 gives a summarized overview of the investigations that follow in the work-up of CVS.

| All of the following criteria must be met to fulfil the definition of CVS |

| At least 5 attacks in any interval, or A minimum of 3 attacks during a 6-mo period |

| Episodic attacks of intense nausea and vomiting lasting 1 h 10 d and occurring at least 1 wk apart |

| Stereotypical pattern and symptoms in the individual patient |

| Vomiting during attacks occurs at least 4 times/h for at least 1 h |

| Return to baseline health between episodes |

| Not attributed to another disorder |

Serum electrolytes are often assessed in the acute setting, prior to starting intravenous fluid therapy. This often reveals a high anion gap metabolic acidosis in keeping with on-going ketosis during an acute attack which resolves with intravenous hydration. Persistence of electrolyte abnormalities or metabolic acidosis may suggest an underlying metabolic, endocrine or renal disorder. Plasma lactate, ammonia, amino acid and acylcarnitine profiles as well as urine organic acid profile are indicated to exclude inborn errors of metabolism (IEM). Children with mild and/or rarer forms of IEM (such as Succinyl-CoA: 3 Ketoacid CoA transferase deficiency) may present later in life and/or with subtle abnormalities such as hypoglycaemia, persistence of metabolic acidosis/ketosis or a clinical picture of encephalopathy when they are unwell, similar to the presentation of CVS.

Bilious vomiting requires imaging of the gastrointestinal tract to exclude obstructive causes of vomiting such as gut malrotation. Usual imaging options include an abdominal radiograph, contrast/barium study and ultrasound abdomen. Oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy is occasionally done in children with symptoms of oesophagitis that persist beyond vomiting episodes.

Brain imaging is often done to rule out tumours of the central nervous system, especially if there is early morning emesis and neurological findings on examination. Although the role of electro-encephalogram in the diagnostic evaluation of CVS remains uncommon, it has been shown that a mild encephalopathic state often exists during an attack and resolves when the child is well. This mode of investigation may lend further support to the diagnostic evaluation of a child with CVS.

The most controversial and challenging aspects of this disorder are the types of effective treatment, and the duration of medical therapy. No specific therapy has been proven to be effective for CVS in controlled trials. Medical therapy remains the tool to prevent or shorten attacks[15]. Several empiric treatments have been shown to be effective in case series[16]. Treatment can be considered as abortive, supportive and prophylactic.

At the start of an attack, care-givers may try sublingual ondansetron or suppository domperidone to suppress the attack. Sumatriptan has also been reported to be beneficial[17]. Unfortunately in the majority of children, it will not prove possible to abort the episodes of vomiting and many will require a period of hospitalisation.

On admission to the hospital, it is essential to assess the severity of dehydration and commence intravenous fluid containing glucose and electrolytes appropriate for the degree of dehydration. Symptom minimisation is necessary not only to make the child feel more at ease but also to alleviate parental distress. Intravenous ondansetron is an effective anti-emetic agent that has been shown to decrease the duration of an episode by more than 50%[11]. Anti-emetic agents used in adults are avoided as they have the associated risk of extra-pyramidal side effects.

The child should ideally be resting in a quiet environment with minimal lighting. Sedation and anxiolytic agents such as chlorpromazine or lorazepam are important as sleep decreases vomiting frequency. Success with alpha blockade using dexmedetomidine[18] and clonidine[19,20] has been reported for small numbers of patients. Proton pump inhibitors or H2 receptor antagonists should be considered for children who have prolonged or frequent episodes of vomiting.

Limited evidence-based recommendations exist on the use of prophylactic agents in CVS. While patients invariably do well even without long term prophylaxis[21], prophylaxis should be considered in patients who have more than one episode per month, leading to hospitalisations and school absences, and/or with poor response to abortive treatments[14].

Amitryptiline, a tricyclic antidepressant is the first line prophylaxis recommended in children more than 5 years of age[14]. Tricyclics reduce brain-gut and sympathetic autonomic dysfunction by decreasing cholinergic neurotransmission and modulation of alpha adrenoreceptors. A systematic review in 2012 showed good response rates (68%-76%) in both adults and children with CVS[22]. In children less than 5 years old, cyproheptadine, an antihistamine and serotonin receptor antagonist, is recommended as the first-line agent. A response rate of 83% was shown in a small series of 6 patients[23].

Propranolol has shown moderate efficacy and is recommended as second line prophylaxis in children of all age groups[14,24]. L-carnitine, a mitochondrial co-factor involved in long-chain fatty acid transport, is also being used as complementary therapy with satisfactory response rates in small case series[25,26].

Various combination therapies have also been tried. Combination treatment using amitriptyline and L-carnitine was found to reduce symptoms in 76.7% of patients[22]. Another combination protocol using coenzyme Q, L-carnitine plus amitriptyline (or cyproheptadine in < 5 years old) has shown > 75% efficacy in episode prophylaxis[27].

Other agents empirically used for prophylaxis with variable success are anticonvulsants valproate and phenobarbital; erythromycin, coenzyme Q, low estrogen oral contraceptives[14,28].

As with migraine treatment, for patients who are able to identify precipitating factors such as lack of sleep, stressful situations or certain foods, prevention of attacks may be possible. Adapting to a low amine diet and avoidance of identified food triggers such as cheese, chocolate or drinks containing caffeine has been described as a prophylactic regimen for CVS with a response rate of 86%[29,30]. A retrospective review by Lee et al[21] (2012) also found sleep to be the most common non-medical management (46.2%) in both adult and childhood-onset CVS

Among children with CVS, anticipatory anxiety related to life events such as school examinations, family conflicts have often been identified[31]. Hence, it has been postulated that there is a role for psychological treatment in the management of CVS. Unfortunately, literature on specific psychological treatment for CVS is scarce. Consultation with a psychologist may be beneficial in exploring mental stressors and developing techniques for coping with anticipatory anxiety. A case report by Slutsker explored using cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with biofeedback training in a phase oriented manner, targeting on the prevention of symptomatic episodes[32].

The prognosis of CVS is variable. Most children outgrow symptoms during adolescence, some trade cyclic vomiting for migraine headache and others continue to have episodes into adulthood[33].

During the interval periods between attacks, it is crucial for the paediatrician or gastroenterologist to review the child. Not only to establish that the child remains well, but also to identify possible psycho-social overlays that may have resulted with recurrent CVS attacks and resultant school absenteeism and poor performance. In children with severe CVS, psychological support may be crucial, not only for the child but also for the distressed parents.

It would be interesting if more insights can be discovered into the pathogenesis of this disorder. This would certainly improve diagnostic and treatment options. At present, treatment options in children remain limited and treatment outcomes often take days before improvement is noted. Further research in the area comparing psychotherapy such as CBT and biofeedback training protocol to both pharmacotherapy and placebo among children with CVS would be a way forward in the management of CVS.

We thank Dr. Dimple Rajgor for her assistance in editing, formatting and submission of the manuscript for publication.

P- Reviewer: Pavlovic M, Sergi CM S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Withers GD, Silburn SR, Forbes DA. Precipitants and aetiology of cyclic vomiting syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:272-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stickler GB. Relationship between cyclic vomiting syndrome and migraine. Clin Pediatr. 2005;44:505-508. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li BU, Murray RD, Heitlinger LA, Robbins JL, Hayes JR. Is cyclic vomiting syndrome related to migraine? J Pediatr. 1999;134:567-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang Q, Ito M, Adams K, Li BU, Klopstock T, Maslim A, Higashimoto T, Herzog J, Boles RG. Mitochondrial DNA control region sequence variation in migraine headache and cyclic vomiting syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;131:50-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cullen KJ, Ma Cdonald WB. The periodic syndrome: its nature and prevalence. Med J Aust. 1963;50:167-173. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. Cyclical vomiting syndrome in children: a population-based study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;21:454-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 7. | Ertekin V, Selimoğlu MA, Altnkaynak S. Prevalence of cyclic vomiting syndrome in a sample of Turkish school children in an urban area. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:896-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mortimer MJ, Kay J, Jaron A. Clinical epidemiology of childhood abdominal migraine in an urban general practice. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1993;35:243-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fitzpatrick E, Bourke B, Drumm B, Rowland M. The incidence of cyclic vomiting syndrome in children: population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:991-995; quiz 996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fleisher DR, Gornowicz B, Adams K, Burch R, Feldman EJ. Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome in 41 adults: the illness, the patients, and problems of management. BMC Med. 2005;3:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li BU, Balint JP. Cyclic vomiting syndrome: evolution in our understanding of a brain-gut disorder. Adv Pediatr. 2000;47:117-160. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Li BU, Fleisher DR. Cyclic vomiting syndrome: features to be explained by a pathophysiologic model. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:13S-18S. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Forbes D, Fairbrother S. Cyclic nausea and vomiting in childhood. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37:33-36. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Li BU, Lefevre F, Chelimsky GG, Boles RG, Nelson SP, Lewis DW, Linder SL, Issenman RM, Rudolph CD. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of cyclic vomiting syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:379-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fleisher DR, Matar M. The cyclic vomiting syndrome: a report of 71 cases and literature review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:361-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Boles RG, Chun N, Senadheera D, Wong LJ. Cyclic vomiting syndrome and mitochondrial DNA mutations. Lancet. 1997;350:1299-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Sudel B, Li BU. Treatment options for cyclic vomiting syndrome. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2005;8:387-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Khasawinah TA, Ramirez A, Berkenbosch JW, Tobias JD. Preliminary experience with dexmedetomidine in the treatment of cyclic vomiting syndrome. Am J Ther. 2003;10:303-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Palmer GM, Cameron DJ. Use of intravenous midazolam and clonidine in cyclical vomiting syndrome: a case report. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abraham MB, Porter P. Clonidine in cyclic vomiting. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:219-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee LY, Abbott L, Moodie S, Anderson S. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in 28 patients: demographics, features and outcomes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:939-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee LY, Abbott L, Mahlangu B, Moodie SJ, Anderson S. The management of cyclic vomiting syndrome: a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1001-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Andersen JM, Sugerman KS, Lockhart JR, Weinberg WA. Effective prophylactic therapy for cyclic vomiting syndrome in children using amitriptyline or cyproheptadine. Pediatrics. 1997;100:977-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Haghighat M, Rafie SM, Dehghani SM, Fallahi GH, Nejabat M. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in children: experience with 181 cases from southern Iran. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1833-1836. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Van Calcar SC, Harding CO, Wolff JA. L-carnitine administration reduces number of episodes in cyclic vomiting syndrome. Clin Pediatr. 2002;41:171-174. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | McLoughlin LM, Trimble ER, Jackson P, Chong SK. L-carnitine in cyclical vomiting syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Boles RG. High degree of efficacy in the treatment of cyclic vomiting syndrome with combined co-enzyme Q10, L-carnitine and amitriptyline, a case series. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Welch KM, Darnley D, Simkins RT. The role of estrogen in migraine: a review and hypothesis. Cephalalgia. 1984;4:227-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Paul SP, Barnard P, Soondrum K, Candy DC. Antimigraine (low-amine) diet may be helpful in children with cyclic vomiting syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:698-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hannington E. Migraine. Clinical Reaction to Food. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons 1983; 155-180. |

| 31. | Tarbell S, Li BU. Psychiatric symptoms in children and adolescents with cyclic vomiting syndrome and their parents. Headache. 2008;48:259-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Slutsker B, Konichezky A, Gothelf D. Breaking the cycle: cognitive behavioral therapy and biofeedback training in a case of cyclic vomiting syndrome. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15:625-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dignan F, Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. The prognosis of childhood abdominal migraine. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:415-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |