Published online Sep 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i3.104096

Revised: March 5, 2025

Accepted: April 27, 2025

Published online: September 9, 2025

Processing time: 165 Days and 20.3 Hours

Gastrointestinal diseases in young children are often anatomic or inflammatory in nature and can present with symptoms similar to those of Cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA), complicating diagnosis. This case series highlights 3 pediatric patients initially misdiagnosed with CMPA, emphasizing the need for a thorough evaluation.

Case 1: A 3-year-old child with chronic abdominal distension and constipation was initially treated for CMPA and was later diagnosed with Hirschsprung disease through rectal biopsy. Surgical intervention involved a laparoscopic colostomy followed by a pull-through procedure, leading to a successful recovery. Case 2: A 2-month-old infant presented with greenish-yellow vomiting and abdominal distension. Initially misdiagnosed with CMPA, further investigation using barium studies revealed partial intestinal malrotation. The patient under

Thorough evaluation of gastrointestinal symptoms is necessary in children. A high suspicion for alternative diagnoses will prevent delays in accurate diagnosis and proper treatment, leading to improved outcomes.

Core Tip: This case series highlights the importance of differential diagnosis in pediatric gastrointestinal cases. In this case series, 3 pediatric patients were initially misdiagnosed with cow’s milk protein allergy, leading to a delay in timely and appropriate surgical interventions. A thorough evaluation and a high suspicion for alternative diagnoses, including Hirschsprung’s disease, intestinal malrotation, and achalasia, are crucial for improving patient outcomes for children.

- Citation: Shah R, Belsha D, Thomas A, Alsweed A. High suspicion unveils Hidden pathology of pediatric gastrointestinal surgical cases misidentified as medical: Three case reports. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(3): 104096

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i3/104096.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i3.104096

Pediatric gastrointestinal diseases are primarily caused by anatomical abnormalities or inflammation in the small or large intestines. Both causes can lead to partial or complete obstruction of the bowels. Large bowel obstruction is much less common than small bowel obstruction, which accounts for 80% of bowel obstruction cases[1]. Small bowel obstruction is also the most frequent indication for surgery on the small intestines. Symptoms of bowel obstruction, in general, include abdominal pain, distension, nausea, vomiting, and constipation.

In rare cases a bowel obstruction may remain undetected. Detailed medical history-taking, risk factor evaluation, and meticulous examination are required for accurate diagnosis, especially when signs and symptoms are unclear as is common in patients with partial obstruction[2] or when other diseases are present. We present herein a case series of 3 young children who presented with upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms of congenital etiology. Interestingly, the common feature among the 3 cases was an initial diagnosis of and treatment for cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA).

Case 1: A 3-year-old male presented with abdominal distension and constipation, both of which had persisted for several months.

Case 2: A 2-month-old female presented with greenish-yellow vomiting that occurred regularly.

Case 3: A 6-month-old male presented with persistent vomiting and severe failure to thrive.

Case 1: The patient had experienced abdominal distension and constipation along with intermittent blackish stool for his entire life. Conservative treatment (with laxatives) had been prescribed by a gastroenterologist, when blood in the stool had prompted the initial diagnosis for CMPA.

Case 2: The patient’s oral intake was good. She had regular bowel movements that were normal in color and consistency. The initial diagnostic testing, including barium studies (which were normal), had been performed at another health care facility and yielded the diagnosis of CMPA and consequent placement on an exclusion diet.

Case 3: The patient had experienced good weight gain from birth until 3 months of age. He then began experiencing frequent episodes of non-bilious vomiting that progressed to vomiting after each feeding. There were no instances of diarrhea, jaundice, abdominal swelling, perianal rash, nor recurrent infections. He had been diagnosed previously with CMPA and, as such, was switched to a cow’s milk protein-free formula, but his symptoms did not improve. Developmentally, the patient was unable to sit and reach for objects, but he was able to roll and was alert, smiling, and interacting with his parents.

Case 1: At birth, the patient experienced a delay in the passage of stool that lasted for the first 4 days of life.

Case 2: There was no significant medical history.

Case 3: The patient was born at term without any risk factors, at a weight of 3.2 kg. He was gaining weight initially but by the time he presented to our facility, he had dropped to less than the 0.4 percentile.

Cases 1-3: No significant personal or family history.

Case 1: The patient’s abdomen was soft and significantly distended. Anal examination revealed mild soiling but anatomical normality.

Case 2: The patient’s abdomen was obviously distended and gassy. Her perianal area showed mild perianal erythema but normal anal position. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

Case 3: The patient was dehydrated and significantly malnourished, with reduced subcutaneous fat and muscle bulk. The patient’s cry was unusual with stridor, and he had an anxious look with irritability.

Case 1: Complete blood count, total tissue transglutaminase IgA, and thyroid function tests were performed, all with normal results.

Case 2: No laboratory testing was conducted.

Case 3: Baseline investigations and tests of renal function, liver function, total immunoglobulins, and thyroid function were performed, all with normal results.

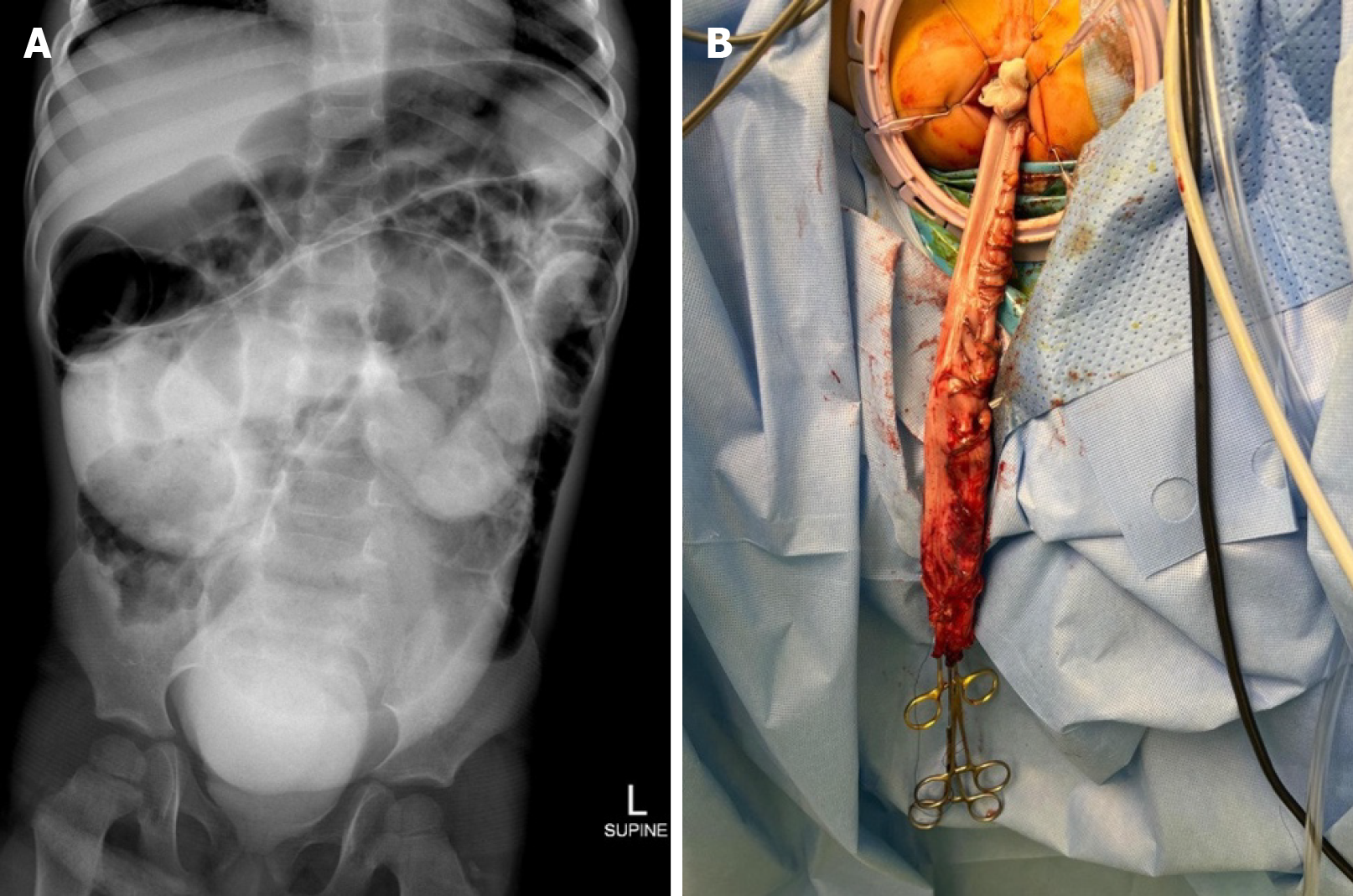

Case 1: Abdominal X-ray revealed irregular pathological dilatation of bowel loops in the upper and central abdomen, in association with colon fecal loading on both sides of the abdomen. Barium enema was planned due to suspicion of Hirschsprung’s disease. Contrast computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed opacification of a markedly distended colon in the central abdomen and pelvis (Figure 1A).

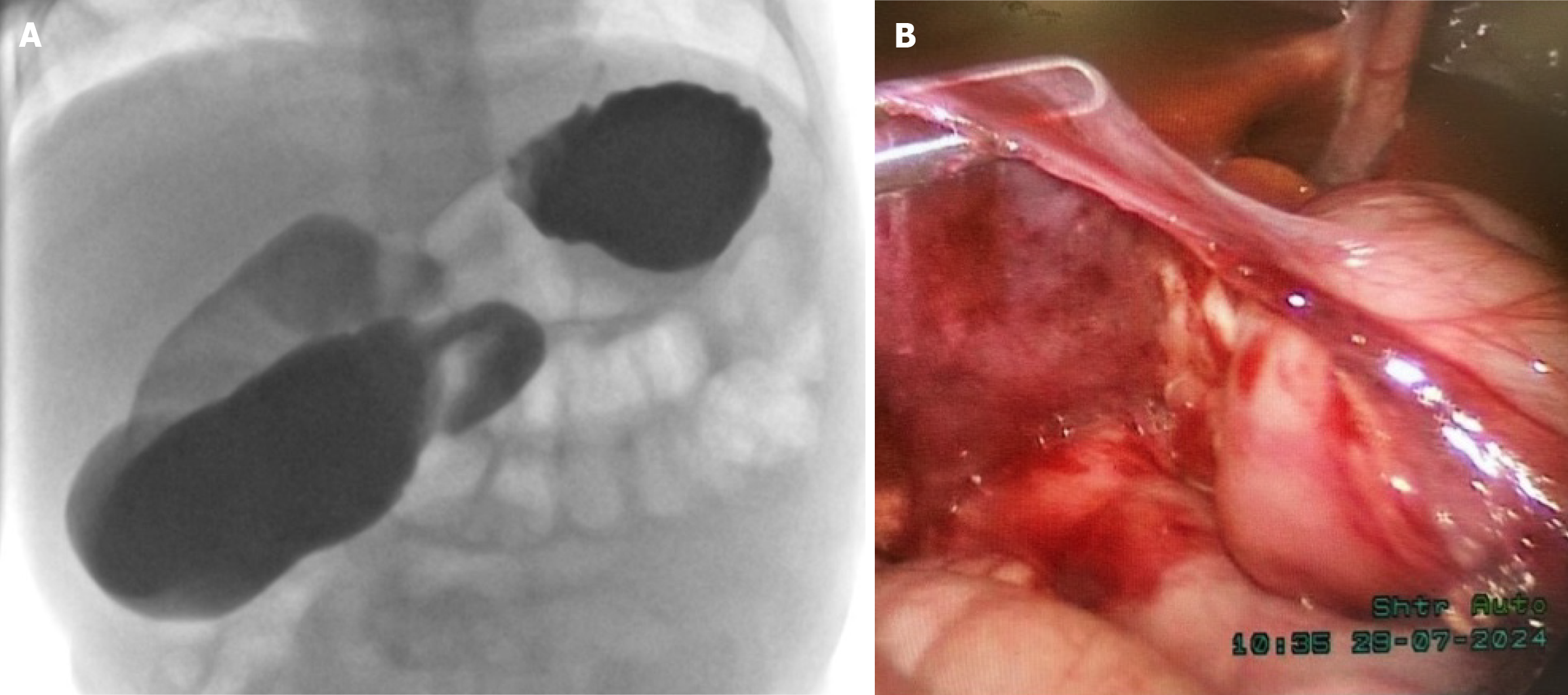

Case 2: Barium swallow test revealed that the duodenal jejunal junction did not cross the midline to the left of the left-sided vertebral body pedicle and appeared inferior to the duodenal bulb (Figure 2A). Small bowel loops were identified primarily on the right side of the abdomen; no small bowel loops were detected on the left side of the abdomen. The visualized colon, from the hepatic flexure, appeared to follow a normal course. The ascending colon was difficult to identify. These findings were highly suggestive of partial malrotation/incomplete rotation. Chest X-ray also revealed an incidental finding of bifid vertebrae at the thoracic cage.

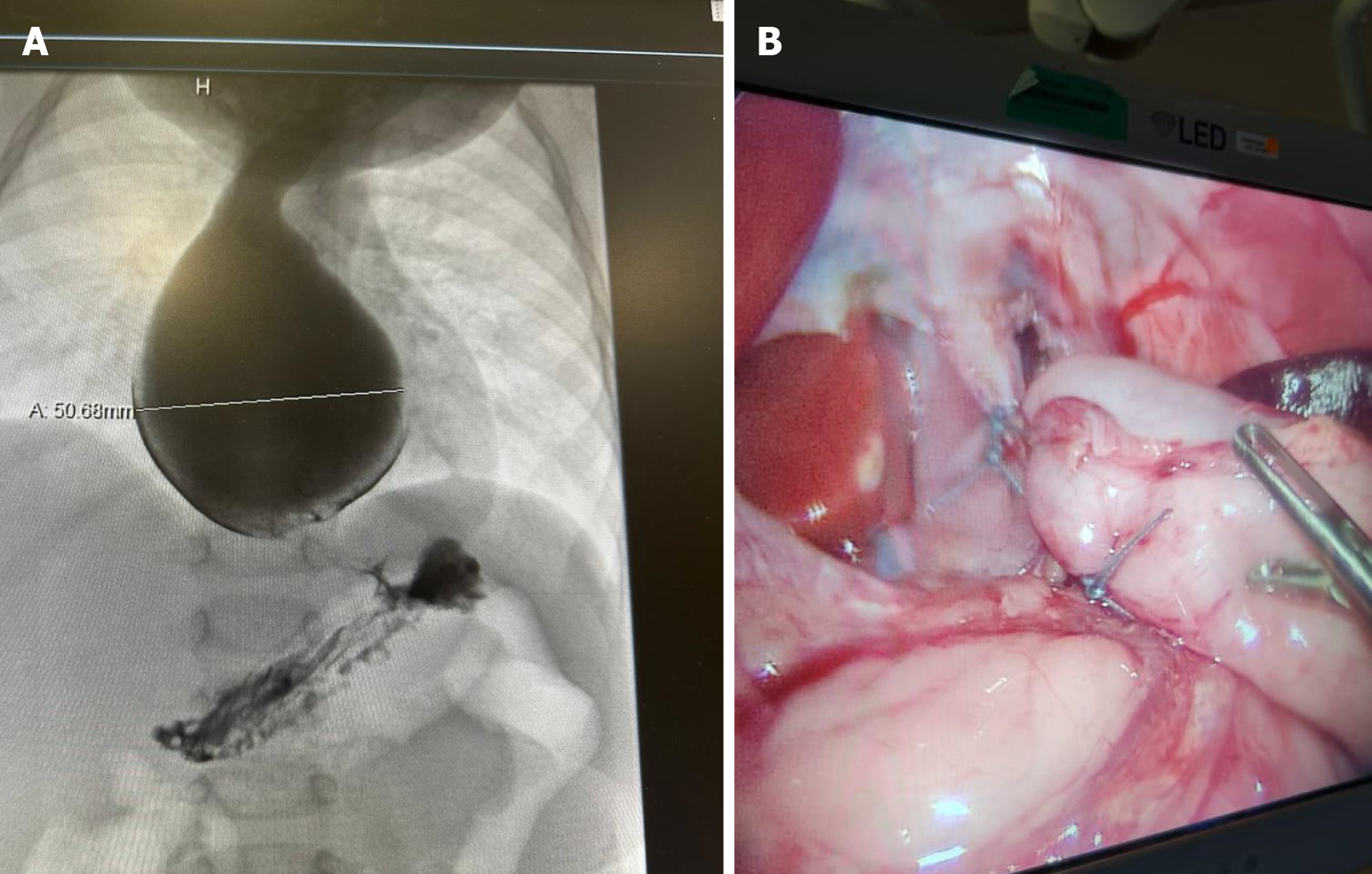

Case 3: Abdominal ultrasound revealed calcific sludge/stone within the gallbladder with no wall thickening. Prominent pylorus muscles were observed, possibly suggesting pyloric stenosis. Barium swallow test revealed a markedly dilated thoracic esophagus, measuring up to 5 cm in the maximum transverse diameter on the delayed images. Marked distal narrowing at the esophagogastric junction was also observed, with a characteristic bird beak sign (Figure 3A). On the delayed 1-h image, there was persistent contrast pooling within the esophagus and very limited contrast flow into the stomach. No esophageal diverticula nor contrast extravasation was seen.

The patient was managed by a team from pediatric gastroenterology and pediatric surgery.

After rectal biopsy revealed a focal absence of ganglion cells involving approximately 3 cm of the distal segment of bowel, the patient was diagnosed with Hirschsprung’s disease.

The patient was diagnosed with partial malrotation/incomplete rotation of the small bowel.

The patient was diagnosed with achalasia.

Laparoscopic colostomy was performed to alleviate acute symptoms, with the decision to recommend definitive treatment after recovery from the acute symptoms. Laparoscopic pull-through proctectomy (Figure 1B) was performed 2 months later and was followed by colostomy reversal.

The patient underwent laparoscopic Ladd’s procedure (Figure 2B). We also performed an appendectomy and umbilical hernia repair.

First, the patient was admitted for rehydration, monitoring, and a detailed workup. He started on an amino acid formula. A chest and abdominal CT were performed to rule out other anatomical abnormalities, and then a laparoscopic Heller myotomy (Figure 3B) was performed.

The patient had an uneventful recovery and remained well and symptom-free throughout the follow-up visits.

The patient had an uneventful postoperative period. She experienced good weight gain and complete resolution of symptoms throughout the follow-up visits.

The patient had a brief and uneventful postoperative hospital stay. Beyond that, he had an overall outstanding outcome. He was started on full feeds and experienced excellent weight gain throughout the follow-up visits.

The patients described in this case series were initially misdiagnosed with CMPA due to overlapping symptoms with the actual diagnoses. This unfortunately delayed the surgical treatments that would ultimately resolve their symptoms. In all cases, the patients were initially managed conservatively, and this led to failure to thrive in these pediatric patients.

Our first patient was diagnosed with Hirschsprung’s disease. Hirschsprung’s disease is a congenital disorder involving the terminal rectum and will occasionally extend proximally. It is characterized by the absence of ganglion cells at the Meissner’s plexus (submucosa) and Auerbach’s plexus (muscularis) of the affected part of the large bowel. Hirs

Hirschsprung’s disease should be suspected if an X-ray reveals colonic dilatation as a feature of large bowel ob

The second patient was diagnosed with intestinal malrotation. Intestinal malrotations are a congenital anomaly resulting from abnormal or incomplete rotation and fixation of the midgut during development. In 75% of cases intestinal malrotation will present as sudden bilious vomiting in the neonatal period. Abdominal X-ray findings of malrotation include an abnormally located bowel (i.e. small bowel markings on the right, and large bowel markings on the left). CT can also reveal right-sided small intestine and a left-sided cecum. Upper gastrointestinal contrast studies are the gold standard for confirming the diagnosis of malrotation.

More than 90% of cases are diagnosed during infancy. If malrotation is not diagnosed until later in life, the patient will present with less dramatic clinical manifestations, including occasional vomiting, intermittent cramps, gastroesophageal reflux, early satiety, and mild abdominal discomfort. These vague gastrointestinal symptoms are due to intermittent volvulus and partial obstruction. Diagnosis is more difficult as the patient ages because the symptoms are more vague. In a retrospective study conducted over a period of 5 years, only 11 patients were diagnosed beyond infancy (from 14 months to 18 years of age)[5]. Our patient was misdiagnosed with CMPA/gastroesophageal regurgitation as an infant. She was initially treated with an exclusion diet but saw no improvement.

The third patient was diagnosed with achalasia. Achalasia is believed to occur from the degeneration of the myenteric plexus of the lower esophageal sphincter resulting in its failure to relax. Patients present with chest pain, dysphagia, regurgitation, nocturnal cough, heartburn, hiccups, and weight loss.

The best initial test to diagnose achalasia is a barium swallow. The characteristic finding on the barium swallow is the dilatation of the proximal esophagus and tapering of the lower esophagus to a bird’s beak appearance. There is also a lack of peristalsis observed during fluoroscopy. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy is suggested for all patients with suspected achalasia, to exclude premalignant or malignant lesions. The gold standard and most sensitive test for the diagnosis of achalasia is esophageal manometry.

Treatment options can be nonsurgical and include pharmacotherapy, endoscopic botulinum toxin injection, or pneumatic dilatation. Surgical treatment options include laparoscopic Heller myotomy and peroral endoscopic myotomy. Common complications after treatment include esophageal perforation, recurrence, gastroesophageal reflux disease, bloating, and a potential risk of cancer[6]. Our patient was treated for several months to relieve the misdiagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux and CMPA, which was unsuccessful.

This case series emphasized the importance of suspecting alternative diagnoses in pediatric patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. The misdiagnosis of these three pediatric cases, due to the absence of a typical clinical presentation, led to delays in the appropriate surgical intervention. Upon further investigation and re-evaluation when conservative treatment for a well-known and common disorder failed, each case was diagnosed correctly and treated properly. The surgical interventions resulted in significant improvements in symptoms and weight gain postoperatively in our 3 patients. All clinicians must remain vigilant and consider comprehensive evaluations when faced with ambiguous clinical presentations to ensure timely and effective treatment for patients.

| 1. | Smith DA, Kashyap S, Nehring SM. Bowel Obstruction(Archived). 2023 Jul 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Vaos G, Misiakos EP. Congenital anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract diagnosed in adulthood--diagnosis and management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:916-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gupta AK, Guglani B. Imaging of congenital anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:403-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lotfollahzadeh S, Taherian M, Anand S. Hirschsprung Disease. 2023 Jun 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Menghwani H, Piplani R, Yhoshu E, Jagdish B, Sree BS. Delayed Presentation of Malrotation: Case Series and Literature Review. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2023;28:271-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |