Published online Sep 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i3.101468

Revised: February 9, 2025

Accepted: March 4, 2025

Published online: September 9, 2025

Processing time: 274 Days and 1.8 Hours

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal (GI) disease (EGID) beyond eosinophilic esophagitis is not commonly reported in the developing world.

To estimate the prevalence of EGID in a selected group of pediatric patients suffering from non-functional chronic abdominal pain (CAP).

A retrospective analysis was conducted on case records of children with CAP. Those exhibiting clinical or laboratory alarming features underwent endoscopic evaluation. Histopathology reports from upper GI endoscopy and ileo-colonoscopy determined the diagnosis of EGID. Subsequent analyses included clinical presentations, presence of atopy in the children or family, hemoglobin, albumin, serum immunoglobulin E (IgE), fecal calprotectin levels, endoscopic appearances, treatment methods, and outcomes.

A total of 368 children with organic CAP were subjected to endoscopic evaluation. Among them, 19 (5.2%) patients with CAP were diagnosed with EGID. The median age of the children was 11.1 years (interquartile range = 8.4-14.4). The estimated prevalence of EGID in children with organic CAP was 520/10000 children over 5 years. Periumbilical pain was the most common site (63%). Family history of atopy, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE were the three parameters significantly associated with EGID. Clinical remission was obtained in all children at 6 months. The 47% had microscopic remission and maintained remission until a 1-year follow-up. The 53% had a fluctuating clinical course after 6 months.

EGID beyond the esophagus is not an uncommon entity among the children of India. It can contribute significantly to the etiology of pediatric CAP.

Core Tip: Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease (EGID) is often an underdiagnosed cause of chronic abdominal pain (CAP) in children. This study estimated how frequently EGID is responsible for the significant pain some of these children experience. This study is unique because although abdominal pain is the most common symptom of EGID, its prevalence in CAP cases has rarely been explored. Additionally, this study uncovered key features of EGID, such as clinical and endoscopic findings, fecal calprotectin levels, presence or absence of atopy, serum immunoglobulin E levels, and response to treatment. These findings contribute valuable insights to the growing knowledge of EGID in children.

- Citation: Acharyya BC, Mukhopadhyay M, Chakrabarty H. Non-esophageal eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease and chronic abdominal pain in children: A multicenter experience. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(3): 101468

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i3/101468.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i3.101468

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal (GI) disease (EGID) is an uncommon entity that, most commonly, presents with abdominal pain[1]. With the spread of the allergy web worldwide, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has been established as a unique disease entity. India is not exempted from this allergy web. However, there are minimal published data regarding the prevalence of pediatric EGID from Indian or Asian countries. As mentioned, abdominal pain is the most common manifestation of EGID[1]. Chronic abdominal pain (CAP) is a common manifestation of GI diseases in outpatients with pediatric gastroenterology. Many of these children evolve as suffering from functional GI disorder. However, children with alarming features are usually thoroughly evaluated to identify the etiological diagnosis of organic pain. Although abdominal pain is one of the commonest manifestations of EGID, to date, no study has highlighted the fraction of patients with EGID among these children with organic CAP.

Therefore, this study was designed primarily to estimate the prevalence of eosinophilic GI diseases, excluding EoE, in a cohort of young patients presenting to pediatricians with non-functional CAP. Furthermore, the study elucidated the clinical, laboratory, and endoscopic characteristics, along with treatment outcomes, for this population.

A retrospective analysis of case records of children presenting with CAP and investigated with the endoscopic study was done from two tertiary centers (AMRI Hospitals and Institute of Child Health [ICH]) of Kolkata, India.

Case records of children aged 5-18 years presenting with CAP in outpatients or wards from January 2015 to December 2019, who had undergone upper GI endoscopy and ileo-colonoscopy, were selected. CAP was defined as regular or intermittent abdominal pain in a child for 2 months or more. Any of the following symptoms had to be present for those children to be subjected to an endoscopic evaluation: (1) Significant pallor; (2) Tender abdomen; (3) Rash; (4) Bloody diarrhea; (5) Fatigue; (6) Joint pain; (7) Weight loss; (8) Unexplained fever; and (9) Investigations showing elevated C reactive protein (CRP), decreased albumin, and elevated fecal calprotectin.

We included children with CAP undergoing upper GI endoscopy or both upper GI endoscopy and colonoscopy whose histopathology showed mucosal eosinophilia.

Children with eosinophilia in GI biopsy specimens who had secondary causes of eosinophilia such as parasitic infestation, celiac disease, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and recent ingestion of drugs eliciting GI symptoms.

All children with CAP, in the centers mentioned above, were usually investigated initially with fecal calprotectin, ultrasound of the whole abdomen, urine routine test, three consecutive stool routine tests and blood tests consisting of complete blood count, CRP, random or fasting blood sugar, liver function test, celiac screening, lipase, urea, creatinine, and thyroid function screening. Any abnormalities in these tests were noted. Children with either clinical and/or laboratory alarming features were selected for endoscopic evaluation. A calprotectin level of more than 200 µmg/mg of stool was defined as an alarming feature. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin (Hb) less than 10 mg/dL, and hypoalbuminemia was defined as serum albumin less than 3 mg/dL. Eosinophilia in peripheral blood was defined as > 500 eosinophils/dL of blood.

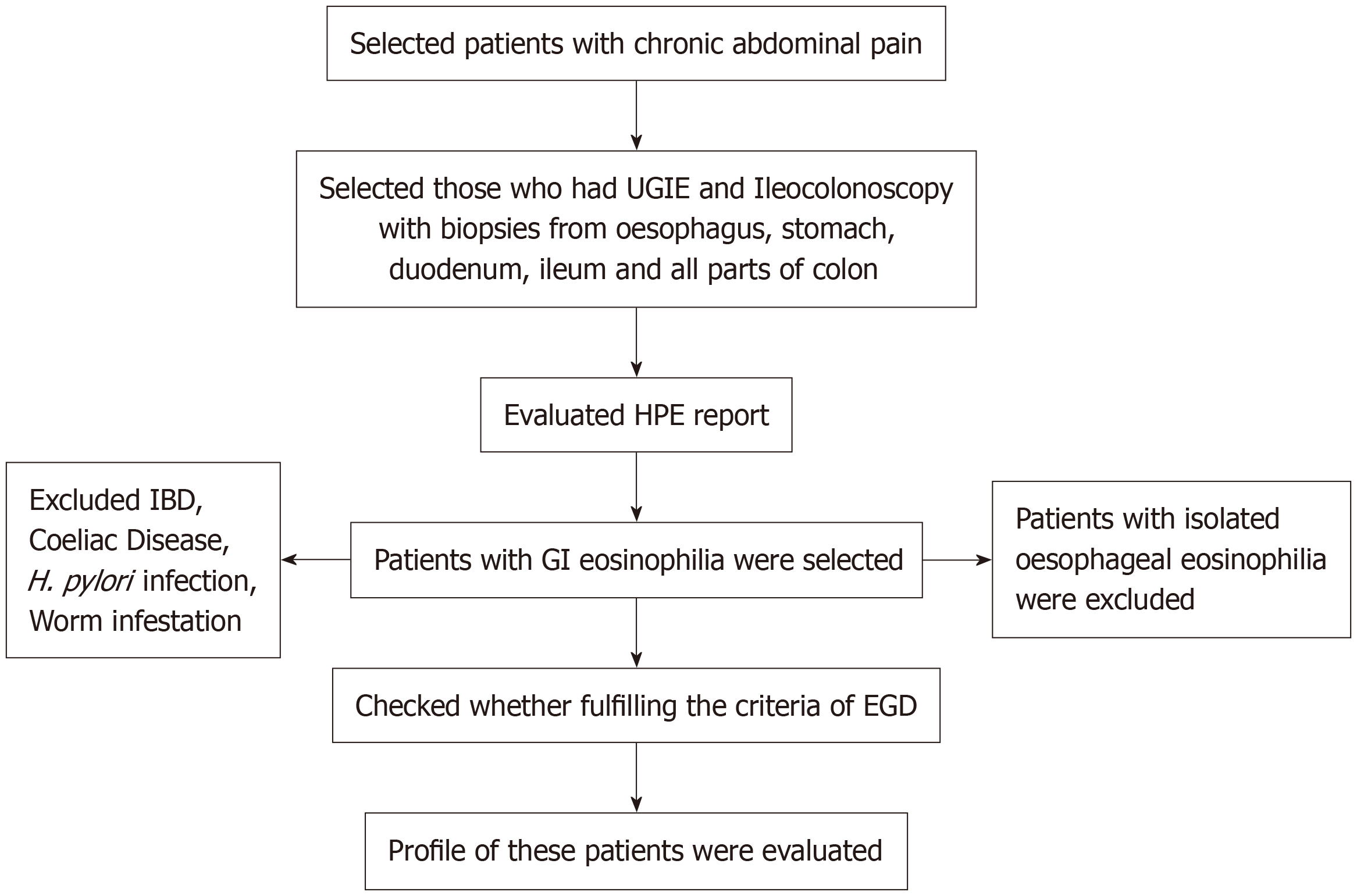

Following an EGID diagnosis, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the entire abdomen with oral and intravenous contrast was performed on a few patients who presented with vomiting in the presence of ileal or colonic disease to rule out small intestinal obstruction or a suspicion of muscular GI eosinophilia. Serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) was measured in all cases. Food allergy testing with the Phadiatop Immunocap approach was described in a few patients, but itwas recommended for all. From the list of patients undergoing endoscopy and/or colonoscopy, histopathology reports of all children were procured and scrutinized to identify those children diagnosed with EGID on histopathology. If the histopathology had not been assessed by the designated histopathologist, slides/blocks were reanalyzed by the same histopathologist again to reconfirm the diagnosis. After finding this subset of children, their case records were carefully analyzed to identify any secondary causes of eosinophilia, clinical presentations, presence of atopy in the children or the family, Hb, albumin, serum IgE, fecal calprotectin values, and endoscopic appearances and treatment outcomes. Treatment consisted of corticosteroids along with dietary milk and soya exclusion. Follow-up records of all patients, defined as EGID, were analyzed if found (Figure 1).

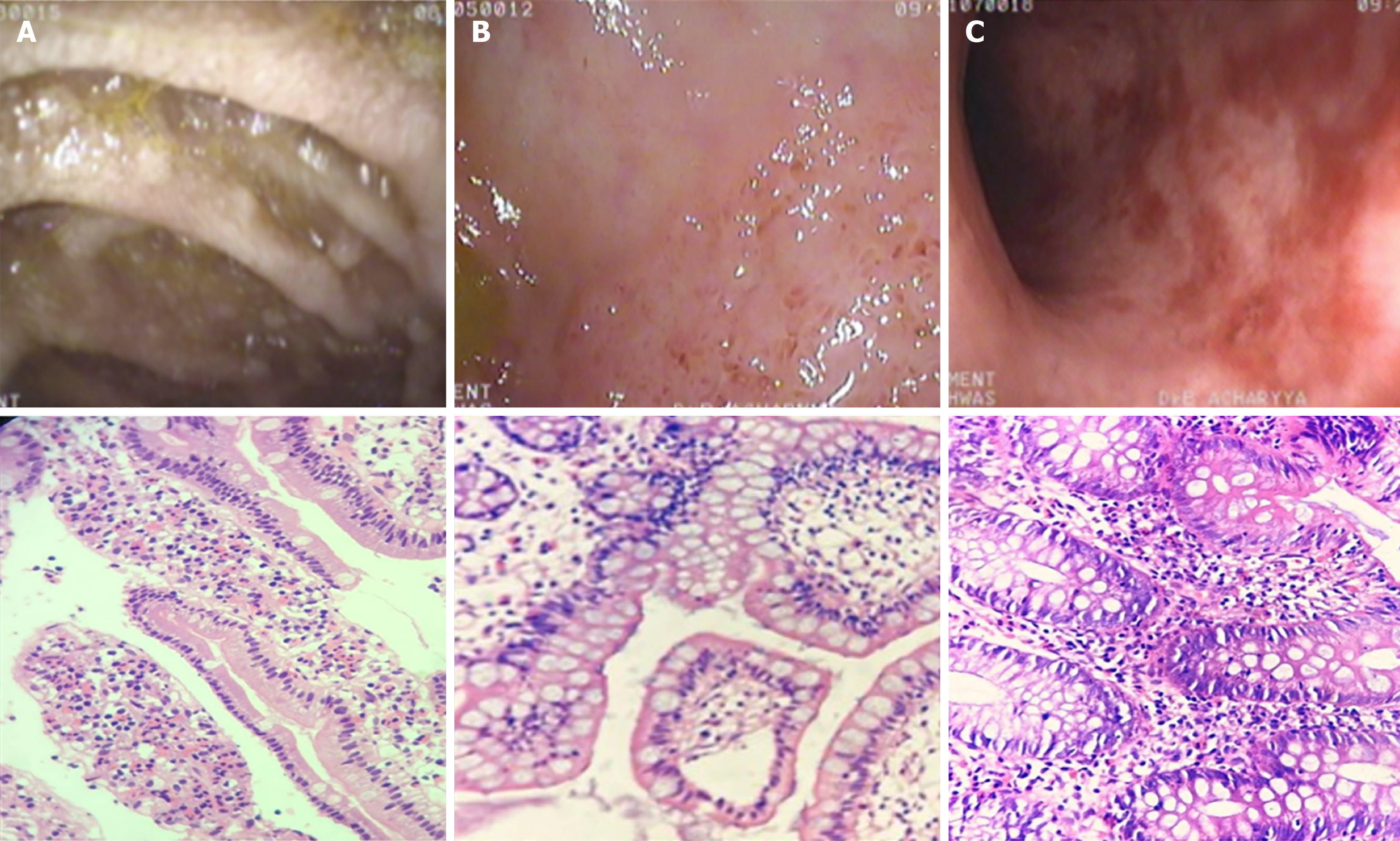

Each child undergoing endoscopic evaluation had multiple biopsies taken from the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, ileum, cecum, colon, (right, transverse and left), and rectum (Figure 2). Biopsies were sent to a single experienced histopathologist (if, during analysis, it was found to be reported by someone else, slides were reviewed again by the same pathologist). EGID was diagnosed as infiltration of eosinophils in mucosa and submucosa at > 25 eosinophils/high-power field (HPF) in the stomach, duodenum and ileum; > 50 eosinophils/HPF in the cecum and right colon; and > 30 eosinophils/HPF in the rest of the colon[2]. A recently published ESPGHAN position paper[3] defined these numbers slightly differently, but diagnoses and this retrospective analysis were undertaken a long time ago, so different criteria were followed at that time. Inflammatory bowel disease was carefully excluded in all cases.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the institutional ethics committee at both ICH (No. ICH-IEC/230/2020) and AMRI Hospitals (No. AMRI-MKP-EC/AP03/2022).

Simple statistical calculations were conducted using basic statistical methods using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 26. Continuous variables are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the relationship between two categorical variables.

A total of 368 individuals with CAP underwent endoscopic assessment. Twenty-three patients were found to have significant eosinophilic infiltration of the GI tract, barring children with exclusive EoE. Two had documented helminthic infestation and two others were subsequently diagnosed with Crohn’s disease. So, these 4 children were excluded from the study analysis. As a result, 19 (5.2%) patients with organic CAP were diagnosed with EGID. In this subset of children with chronic abdominal discomfort, the estimated prevalence of eosinophilic GI illness was 520/10000 children over a 5-year period. The male:female ratio in this group of 19 was 8:11. The median age of children was 11.1 years (IQR = 8.4-14.4).

Regarding the distribution of abdominal pain, 4 (21%), 12 (63.2%), and 11 (57.9%) children had epigastric, periumbilical, and lower abdominal pain, respectively. Apart from abdominal pain, children had various other clinical features, namely vomiting, nausea, and chronic watery diarrhea and bloody diarrhea, which were present in 7 (36.8%), 4 (21%), and 7 (36.%) children, respectively. History of atopy was present in 8 (42%) children, but a family history of atopy was present in 11 (58%) children. Among the atopic manifestations, bronchial asthma was predominant as 6 children were diagnosed with it. Surprisingly ascites or edema was absent in all children. The mean Hb level in these 19 children was 10.4 mg/dL ± 1.3 mg/dL, and 8 of them had anemia as per the definition of the present study. Mean albumin in this cohort was found to be 3.6 ± 0.47 with hypoalbuminemia in 4 (21%). Peripheral eosinophilia was found in 10 (53%) children (Table 1).

| Type of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease | Characteristic features | Total | Gastric/ duodenal disease [3 (16)] | Ileal disease [3 (16)] | Colonic disease [7 (37)] | Ileocolonic [5 (26)] | Pan gastrointestinal [1 (5)] | P value |

| Pain abdomen | Epigastric pain | 4 (21) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | NS |

| Periumbilical | 12 (63.2) | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | NS | |

| Lower abdomen | 11 (58) | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | NS | |

| Diarrhea | Chronic diarrhea | 4 (21) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Bloody diarrhea | 7 (37) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | NS | |

| Atopy | Atopy in patient | 8 (42) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | NS |

| F/H of atopy | 11 (58) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | < 0.00001 | |

| Laboratory features | Anemia | 8 (42) | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | |

| Hypoalbuminemia (< 3 mg/dL) | 4 (21) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Peripheral eosinophilia (> 500 cells/dL) | 10 (53) | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | < 0.00001 | |

| Raised serum immunoglobulin E (> 200 iu/mL) | 16 (84) | 3 | 6 | 4 | 1 | < 0.00001 |

Fecal calprotectin values were analyzed in all patients. The median value of fecal calprotectin was 610 mcg/mg (IQR = 478-754 mcg/mg) in the children with EGID. Serum IgE was raised in 16 (84%) children. The mean serum IgE was found to be 432.8 iu/mL. CT scan abnormality of the small bowel was not recorded in any one of them.

Exclusive eosinophilic gastritis (EoG) was found in 1 (5%), and eosinophilic gastro-duodenitis was found in 2 (11%). Ileal (small bowel), colonic (large bowel), and ileocolonic (small bowel and large bowel) eosinophilic disease was present in 3 (16%), 7 (37%), and 5 (26%) children, respectively. One (5%) boy had pan GI involvement, including the esophagus (Table 1).

Four (21%) children (1 in the gastroduodenal group and 3 in the colonic group) had a normal macroscopic appearance on endoscopy. Other lesions/abnormalities seen in endoscopy were gastric erythema with or without ulcerations in 5 (2 only erythema and 3 both; i.e. in 26%); duodenal lymphoid nodular hyperplasia (LNH) in 7 (37%); colonic ulcers (tiny, aphthoid, and deep ulcers involving one or more segments continuous or patchy) in 10 (53%), and ileal LNH with or without ulcers in 6 (32%) (3 had only LNH and 3 had both) (Table 2).

| Type of eosinophilic gastro-intestinal disease | Characteristic features | Total (n = 19) | Gastric/duodenal disease [3 (16)] | Ileal disease [3 (16)] | Colonic disease [7 (37)] | Ileocolonic [5 (26)] | Pan gastrointestinal [1 (5)] |

| Endoscopic appearance | Normal | 5 (26) | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Gastric erythema and/or ulcers | 5 (26) | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Duodenal LNH | 7 (37) | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Colonic ulcers | 10 (53) | 5 | 5 | ||||

| Ileal LNH and/or ulcers | 6 (32) | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Oral prednisolone was administered at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg for 14 days and then tapered weekly in 14 (74%) patients. Dietary restriction alone was implemented in the remaining 5 (26%) children. A boy with pan GI involvement was kept on swallowed budesonide for EoE after finishing the systemic steroids along with the dietary restrictions. A follow-up record of more than 1 year was obtained for 17 patients. Repeat endoscopy after 6 months showed complete resolution of inflammation with reduction of eosinophil count/HPF in 9 (47%) patients. Incomplete resolution was recorded in the rest. Clinical remission was obtained in all 19 (100%) patients at 6 months (irrespective of histopathology); however, a fluctuating clinical course later was obtained in 10 (53%) patients at variable intervals with the rest 9 (47%) maintaining clinical remission in the next 9 months.

Primary EGID is an idiopathic disease characterized by inflammation dominated by eosinophils in the stomach and/or intestine. EGID barring EoE is an uncommon condition, and the epidemiology, disease spectrum, and outcome have not been described extensively. India being a developing country, there are other causes of secondary eosinophilic disease like parasitic infestation, H. pylori infection, celiac disease, drug allergy, or inflammatory bowel disease to produce secondary GI eosinophilia. This might be a reason for the underreporting of EGID even from large pediatric GI in

The median age of children was 11.1 years (IQR = 8.4-14.4 years). In this study, male:female was 8:11 (slightly female preponderance). This is in contrast to the findings of Talley et al[6] and Pineton de Chambrun et al[7], where there was male preponderance. The sex balance of our study was in concurrence with Reed et al[8]. Klein et al[9] defined EGID in three varieties: (1) Mucosal; (2) Muscular; and (3) Serosal, depending on the layer of GI tract involvement. In realistic terms, all were mucosal varieties of EGID in our study.

In 2011, Lwin et al[10] published a report on EoG. This report considered case records of 50 adults and 10 children with this condition. Epigastric pain was found as the main symptom in 5 children; however, the frequency of abdominal pain as the main symptom could not be ascertained. Alhmoud et al[1] described abdominal pain as the most frequent complaint (62%). This study detected the frequency of EGID in children with chief complaints of abdominal pain only; 21% had epigastric pain, 63% had periumbilical pain and 58% had lower abdominal pain. Ko et al[11] published a report on histological eosinophilic gastritis (HEG) among pediatric patients and found that 43% of the patients had abdominal pain as the main symptom. Reed et al[8] published the profile of 34 pediatric patients with EGID. They included EoE as well. The 62% of children in their data of EoG had abdominal pain.

Clinical manifestations of EGID are heterogeneous, depending on the location, extent, and depth of the inflammatory infiltrate[12]. Apart from abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea and bloody diarrhea were present in 21% and 37% of children, respectively in the present study. Bloody diarrhea was present mainly in children with EoC as previously mentioned by Redondo-Cerezo et al[13]. Patients with diffuse small intestinal disease may develop malabsorption, anemia, and hypoalbuminemia[10]. Anemia was found in 42% of the cases, and hypoalbuminemia was documented in 21% of children. Blood and protein losses in our patients were possibly secondary to an increase in intestinal permeability, as demonstrated by Waldmann et al[14].

Elevated IgE levels indicate that atopy may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease; however, a history of allergy alone is inadequate for diagnosis. In our study, 34% of patients reported a history of allergy, a proportion consistent with findings from other studies. Notably, there was no correlation between allergy history and the histological subtype of the disease[15]. An elevated IgE was found in a considerable number (84%) of children in our study, with a positive significant association in children with CAP. This was higher than that mentioned by Chen et al[15] but similar to Tien et al[16], who found elevated IgE in two-thirds of patients in their series.

A personal or family history of atopic diseases might be present in as many as 70% of patients[17]. Atopy was prevalent in 42% of our cohort, with 58% of them having a family history of atopy. This was a similar finding to studies by Chang et al[18] and Tien et al[16].

Fecal calprotectin before endoscopic evaluation in our cohort was a regular investigation in our protocol but formed a unique finding in this study. The median fecal calprotectin of children with EGID was 610 mcg/mg (IQR = 478-754 mcg/mg), which was rare documentation of fecal calprotectin in EGID. This value of calprotectin was slightly higher than that found in the Korean series by Yoo et al[19].

Endoscopy might show mucosal erythema, edema, ulcerations, nodularity, or polypoid lesions or it might be normal in appearance[1,5]. Five (26%) children of this cohort had normal endoscopy. The rest of the endoscopic appearances included nodularity, erythema, ulcerations, and erosions. In a study by Ko et al[11], endoscopic normality was found to be the most common finding. In this study, none of this subset of children presented with ascites. The reason might be that only mucosal eosinophilia was documented in this endoscopically diagnosed EGID population.

Oral corticosteroids provided symptomatic relief in all the children, similar to the findings in studies by Chang et al[15] and Alhmoud et al[1].

With the availability of limited follow-up information, this study depicted that endoscopic remission was obtained in 9 (47%) children at 6 months. Tien et al[16] depicted that about 50% of their children did not have any relapse, which was comparable to our figure of 47%.

The limitations of this study were that the sample size was not large enough and it had a retrospective design, which potentially limited the data that were available. However, this study provides important information about EGID in our population.

This is the first study to indicate that non-esophageal primary EGID is a significant and often overlooked cause of CAP in children from the developing world. An inference can be drawn that when children present with CAP with some alarm symptoms or signs and celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and common infections like H. pylori or parasitic infestations are excluded, EGID should be specifically searched for an etiology with the help of an experienced histopathologist. Until highly suspected and specifically searched, EGID may remain underdiagnosed, causing significant disability to children.

| 1. | Alhmoud T, Hanson JA, Parasher G. Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: An Underdiagnosed Condition. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2585-2592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Papadopoulou A, Amil-Dias J, Auth MK, Chehade M, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Gutiérrez-Junquera C, Orel R, Vieira MC, Zevit N, Atkins D, Bredenoord AJ, Carneiro F, Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Menard-Katcher C, Koletzko S, Liacouras C, Marderfeld L, Oliva S, Ohtsuka Y, Rothenberg ME, Strauman A, Thapar N, Yang GY, Furuta GT. Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN Guidelines on Childhood Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders Beyond Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024;78:122-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | DeBrosse CW, Case JW, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Rothenberg ME. Quantity and distribution of eosinophils in the gastrointestinal tract of children. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2006;9:210-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jensen ET, Martin CF, Kappelman MD, Dellon ES. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, and Colitis: Estimates From a National Administrative Database. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:36-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Naramore S, Gupta SK. Nonesophageal Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders: Clinical Care and Future Directions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67:318-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Talley NJ, Shorter RG, Phillips SF, Zinsmeister AR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a clinicopathological study of patients with disease of the mucosa, muscle layer, and subserosal tissues. Gut. 1990;31:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pineton de Chambrun G, Gonzalez F, Canva JY, Gonzalez S, Houssin L, Desreumaux P, Cortot A, Colombel JF. Natural history of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:950-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Reed C, Woosley JT, Dellon ES. Clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes, and resource utilization in children and adults with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:197-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Klein NC, Hargrove RL, Sleisenger MH, Jeffries GH. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1970;49:299-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lwin T, Melton SD, Genta RM. Eosinophilic gastritis: histopathological characterization and quantification of the normal gastric eosinophil content. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:556-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ko HM, Morotti RA, Yershov O, Chehade M. Eosinophilic gastritis in children: clinicopathological correlation, disease course, and response to therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1277-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Koutri E, Papadopoulou A. Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases in Childhood. Ann Nutr Metab. 2018;73 Suppl 4:18-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Redondo-Cerezo E, Cabello MJ, González Y, Gómez M, García-Montero M, de Teresa J. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: our recent experience: one-year experience of atypical onset of an uncommon disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1358-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Waldmann TA, Wochner RD, Laster L, Gordon RS Jr. Allergic gastroenteropathy. A cause of excessive gastrointestinal protein loss. N Engl J Med. 1967;276:761-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen MJ, Chu CH, Lin SC, Shih SC, Wang TE. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: clinical experience with 15 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2813-2816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tien FM, Wu JF, Jeng YM, Hsu HY, Ni YH, Chang MH, Lin DT, Chen HL. Clinical features and treatment responses of children with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Pediatr Neonatol. 2011;52:272-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Khan S, Orenstein SR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:333-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chang JY, Choung RS, Lee RM, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Smyrk TC, Talley NJ. A shift in the clinical spectrum of eosinophilic gastroenteritis toward the mucosal disease type. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:669-675; quiz e88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yoo IH, Cho JM, Joo JY, Yang HR. Fecal Calprotectin as a Useful Non-Invasive Screening Marker for Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorder in Korean Children. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |