Published online Jun 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i2.99455

Revised: December 26, 2024

Accepted: January 23, 2025

Published online: June 9, 2025

Processing time: 228 Days and 7.9 Hours

Ureteroneocystostomy (UNC) is considered the gold standard for pediatric vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) treatment. While UNC lowers the likelihood of needing additional VUR procedures within 12 months, patients also have high 30-day and 90-day readmission rates and emergency department (ED) visits. The most common causes of an ED visit following any urologic procedure are urinary tract infections (UTIs) and catheter/drain concerns. Prior studies are limited in identifying predisposing factors to help mitigate complications of UNC and improve patient outcomes.

To identify modifiable characteristics at the time of discharge after UNC that predict subsequent unplanned ED visits.

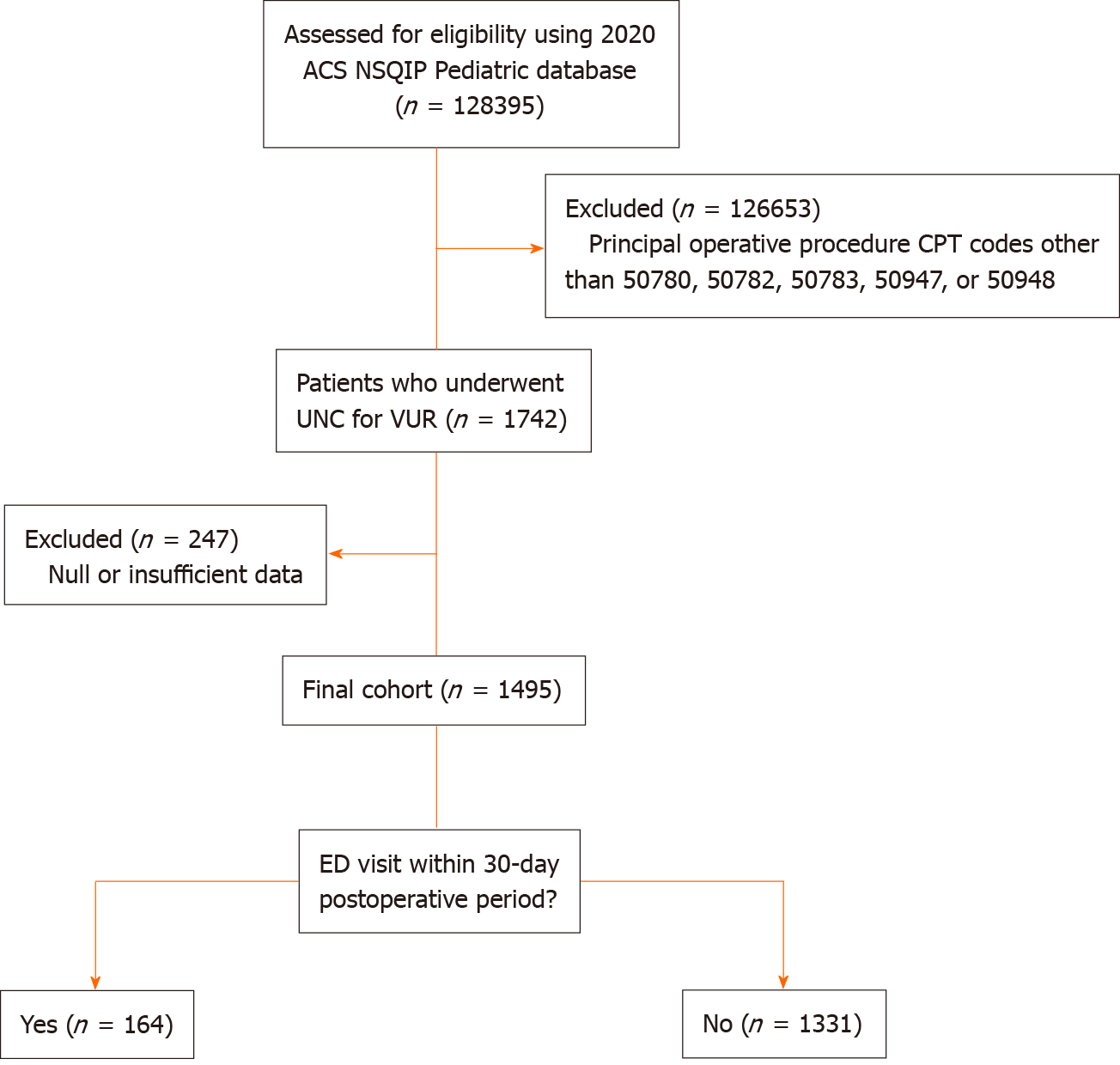

The 2020 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Pediatric data was analyzed for patients undergoing UNC for VUR. A total of 1742 patients were evaluated, with 1495 meeting inclusion criteria. Patients with an ED visit within 30 days following an anti-reflux procedure (n = 164) were compared to those who did not return to the ED (n = 1331). Basic statistics and logistic regression analysis were performed to find predictive factors associated with postoperative ED visits after UNC.

Among the 1495 patients, 11.0% visited the ED within the 30-day postoperative period. Patients who returned to the ED visit following UNC were more likely to have had a longer mean operative time, surgical site infection, postoperative UTI, postoperative sepsis, history of prior readmission, unplanned reoperation, blood transfusion, or unplanned urinary catheter placement. Multivariate analysis revealed postoperative UTI (P < 0.001), superficial surgical site infection (P = 0.022), unplanned procedure (P < 0.001), unplanned urinary catheter (P < 0.001), and prematurity (35-36 weeks gestation) (P = 0.004) as independent risk factors for postoperative ED visits.

Utmost caution is needed prior to discharge after UNC to forestall a return to the ED. Postoperative infection remains a primary risk for ED visits in the acute postoperative period.

Core Tip: Ureteroneocystostomy (UNC) is the gold standard for pediatric vesicoureteral reflux treatment but has high postoperative emergency department (ED) visit rates. Analyzing 2020 data from 1495 patients, we identified key risk factors for ED visits within 30 days post-UNC, including postoperative urinary tract infections, surgical site infections, unplanned procedures, urinary catheter placements, and prematurity. These findings underscore the necessity for stringent discharge protocols to reduce postoperative ED visits, emphasizing the management of infections and other modifiable risk factors to enhance patient outcomes and minimize complications.

- Citation: Son Y, Quiring M, Serpico S, Wu E, Wood E, Deynzer S, Olive W, Henderson B, Choudhry H, Ahmed A, Aljameey U, Terrenzio D, Dean GE. Factors and outcomes leading to postoperative emergency department visits after ureteroneocystostomy. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(2): 99455

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i2/99455.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i2.99455

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is a common pediatric urologic disorder with an estimated incidence of 10% in the United States[1]. Ureteroneocystostomy (UNC) is considered the gold standard surgical treatment for VUR, with the primary goal of preventing recurrent infections and renal scarring[2,3]. However, there is a lack of data evaluating risk factors for adverse outcomes leading to postoperative emergency department (ED) visits after UNC in the pediatric population.

The most common reasons for returning to the ED following a urologic procedure are concerns for a urinary tract infection (UTI) or issues with a catheter or drain[4]. Specific urologic surgeries in the pediatric population have also been identified to have higher rates of return to the ED, such as penile and lower urinary tract procedures[5]. Further, return to the ED within the acute postoperative period is an often underutilized primary endpoint; most studies use rates of readmission as a primary variable of interest when discussing surgical risk, but this fails to include the cohort of patients who return to the hospital for a procedure-related concern that doesn’t warrant admission. The previously cited study identified that only 15.5% of pediatric patients who returned to the ED after a urologic procedure required readmission, while the rest were managed conservatively[5].

As the current literature lacks a comparative breadth of articles focusing on postoperative returns to the ED rather than those who become readmitted to the hospital, the primary objective of this study is to identify predictive factors that lead to higher rates of post-discharge ED visits after UNC in the pediatric population.

The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) is a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant database created by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) to improve quality of care and surgical outcomes. NSQIP includes all major cases determined by the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code. With the NSQIP data consisting of de-identified patient information, this retrospective study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

The 2020 ACS NSQIP Pediatric database was analyzed for patients undergoing UNC for VUR. The principal operative CPT codes included were 50780 (ureteral reimplant), 50782 (ureteral reimplant for duplicated ureter), 50783 (ureteral reimplant with tapering), 50947 (laparoscopic ureteral reimplant with cystoscopy and stent), and 50948 (laparoscopic ureteral reimplant without cystoscopy and stent). Robot-assisted laparoscopic procedures are included under codes 50947 and 50948. Patients with unreported postoperative variables were excluded. The patients were then divided into those who did and did not return to an ED within 0-30 days following their anti-reflux procedure (Figure 1).

Patient demographics, comorbid conditions, and postoperative variables were analyzed. Basic statistics were performed, which included Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables and t-test and Welch-tests for continuous variables. Univariate and multivariate analysis was performed using a random forest model with ED visits as the dependent variable. A variable of significance was included and measured for each independent variable, which was objectively chosen for the logistic regression. Statistical analysis was completed using R Version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

A total of 1495 patients from 124 hospitals met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Among the 1495 patients who underwent UNC, 164 (11.0%) returned to the ED within the 30-day postoperative period (Table 1). Distributions of age, gender, and race were all found to be similar between the two groups. Those who returned to the ED were more likely to be of Hispanic ethnicity (14.0% vs 13.4%, P = 0.01). Patients with postoperative ED visits had an increased incidence of structural pulmonary abnormalities (4.3% vs 1.9%, P = 0.05), gastrointestinal diseases (9.1% vs 5.0%, P = 0.03), and were more likely to have had an ostomy (7.9% vs 4.4%, P = 0.04). Those who returned post-UNC were also more likely to have been born at 35-36 weeks (11.0% vs 3.9%, P < 0.01) and have minor cardiac risk factors (6.1% vs 2.7%, P = 0.02) (Table 2). All other demographic and comorbid variables were similarly distributed between groups. No difference in VUR severity was found between those who returned to the ED postoperatively and those who did not.

| Patient demographics | Total cohort (n = 1495) | Postoperative ED visit (n = 164) | No Postoperative ED visit (n = 1331) | P value1 |

| Age | 1666 ±1208 | 1605.5 ± 1207 | 1673.3 ± 1196 | 0.4974 |

| Male gender | 446 (29.8) | 55 (33.5) | 391 (29.4) | 0.2720 |

| Non-Caucasian race | 304 (20.3) | 38 (23.2) | 266 (20.0) | 0.9070 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 201 (13.4) | 23 (14.0) | 178 (13.4) | 0.0109 |

| Inpatient | 1010 (67.6) | 120 (73.2) | 890 (65.9) | 0.1038 |

| Height | 40.2 ± 8.9 | 39.0 ± 8.3 | 40.3 ± 8.6 | 0.4041 |

| Weight | 42.0 (24.3) | 39.3 (22.5) | 42.2 (24.5) | 0.0696 |

| Comorbid conditions/past medical history | ||||

| Ventilator dependent | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 0.0773 |

| History of asthma | 25 (1.7) | 5 (3.0) | 20 (1.5) | 0.1453 |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia/chronic lung disease | 14 (0.9) | 3 (1.8) | 11 (0.8) | 0.2085 |

| Oxygen support | 10 (0.7) | 2 (1.2) | 8 (0.6) | 0.3594 |

| Tracheostomy | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0.6195 |

| Structural pulmonary/airway abnormalities | 32 (2.1) | 7 (4.3) | 25 (1.9) | 0.0461 |

| Esophageal/gastric/intestinal disease | 81 (5.4) | 15 (9.1) | 66 (5.0) | 0.0254 |

| History of cardiac surgery | 30 (2.0) | 3 (1.8) | 27 (2.0) | 0.8637 |

| Developmental delay/impaired cognitive status | 100 (6.7) | 15 (9.1) | 85 (6.4) | 0.1820 |

| Seizure disorder | 17 (1.1) | 3 (1.8) | 14 (1.1) | 0.3758 |

| Cerebral palsy | 6 (0.4) | 2 (1.2) | 4 (0.3) | 0.0791 |

| Structural CNS abnormality | 65 (4.3) | 9 (5.5) | 56 (4.2) | 0.4482 |

| Neuromuscular disorder | 35 (2.3) | 7 (4.3) | 28 (2.1) | 0.0838 |

| Ostomy | 71 (4.7) | 13 (7.9) | 58 (4.4) | 0.0427 |

| Congenital malformation | 1144 (76.5) | 130 (79.3) | 1014 (76.2) | 0.6228 |

| Childhood malignancy | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.3) | 0.7811 |

| Steroid use (Within 30 days) | 6 (0.4) | 2 (1.2) | 4 (0.3) | 0.0791 |

| Nutritional support | 30 (2.0) | 5 (3.0) | 25 (1.9) | 0.3133 |

| Hematologic disorder | 33 (2.2) | 3 (1.8) | 30 (2.3) | 0.7270 |

| Total cohort (n = 1495) | Postoperative ED visit (n = 164) | No postoperative ED visit (n = 1331) | P value1 | |

| Premature birth | ||||

| 25-30 weeks | 15 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 14 (1.1) | 1.000 |

| 31-34 weeks | 39 (2.6) | 6 (3.7) | 33 (2.5) | 0.4303 |

| 35-36 weeks | 70 (4.7) | 18 (11.0) | 52 (3.9) | 0.0003 |

| Cardiac risk factors | ||||

| Minor | 46 (3.1) | 10 (6.1) | 36 (2.7) | 0.0176 |

| Major | 44 (2.9) | 5 (3.0) | 39 (2.9) | 0.9324 |

| Severe | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | P = 0.5429 |

| VUR disease severity | ||||

| VUR Grade 1 | 40 (2.7) | 7 (4.3) | 33 (2.5) | 0.1805 |

| VUR Grade 2/3 | 446 (29.8) | 50 (30.5) | 396 (29.8) | 0.8460 |

| VUR Grade 4/5 | 887 (59.3) | 95 (57.9) | 792 (59.5) | 0.6981 |

| ASA classification | ||||

| ASA Class 1 | 250 (16.7) | 19 (11.6) | 231 (17.4) | 0.0618 |

| ASA Class 2 | 1060 (70.9) | 119 (72.6) | 941 (70.7) | 0.6204 |

| ASA Class 3 | 177 (11.8) | 25 (15.2) | 152 (11.4) | 0.1528 |

| ASA Class 4 | 6 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (0.4) | 0.6547 |

Postoperatively, patients who returned had a longer mean total operation time (182 mins) on average than those who did not (165 minutes) (P = 0.01). The mean length of stay (22.38 vs 20.09, P < 0.01) and days from operation to discharge (2.13 vs 1.29, P < 0.01) also varied significantly between the two groups. Rates of laparoscopic vs open approach were similar, as were the percentage of patients who underwent unilateral vs bilateral fixation. Patients who returned for an ED visit were found to have higher rates of superficial incisional (1.8% vs 0.2%, P < 0.01) and organ space surgical site infections (SSIs) (1.2% vs 0.1%, P < 0.01). Postoperative UTIs (14.0% vs 1.9%, P < 0.1) and sepsis rates (3.7% vs 0.2%, P < 0.01) were also higher in patients who returned to the ED, although there was no difference in rates of septic shock (P = 0.73) (Table 3). Preoperative/intraoperative urine cultures did not vary between groups. The patients who visited the ED had higher rates of readmission (31.7% vs 1.7%, P < 0.01), progressive renal insufficiency (1.2% vs 0.2%, P = 0.04), unplanned reoperations (7.3% vs 0.8%, P < 0.01), blood transfusions (1.2% vs 0.2%, P = 0.01), unplanned procedures related to the initial UNC (13.4% vs 1.1%, P < 0.01), and unplanned urinary catheterization (17.7% vs 1.2%, P < 0.01).

| Total cohort (n = 1495) | Postoperative ED visit (n = 164) | No postoperative ED visit (n = 1331) | P value1 | ||

| Operative time | |||||

| Total operation time (Minutes) | 166.5 ± 74.3 | 181.8 ± 84.2 | 164.6 ± 72.9 | 0.0130 | |

| Length of hospital stay | |||||

| Length of stay (Days) | 20.3 ± 26.6 | 22.4 ± 43.0 | 20.1 ± 23.8 | 0.5042 | |

| Days from operation to discharge (Days) | 1.8 ± 1.6 | 2.1 ± 2.10 | 1.7 ± 1.47 | 0.0220 | |

| Operative approach | |||||

| Laparoscopic/MIS | 189 (12.6) | 16 (9.8) | 173 (13.0) | 0.2387 | |

| Open or N/A | 1175 (78.6) | 133 (81.1) | 1042 (78.3) | 0.4078 | |

| Laparoscopic/MIS and open | 131 (8.8) | 15 (9.1) | 116 (8.7) | 0.8539 | |

| Unilateral procedure | 692 (46.3) | 73 (48.5) | 619 (46.5) | 0.6392 | |

| Bilateral procedure | 798 (53.4) | 91 (55.5) | 707 (53.1) | 0.5993 | |

| SSI | |||||

| Superficial incisional SSI | 5 (0.3) | 3 (1.8) | 2 (0.2) | 0.0110 | |

| Deep incisional SSI | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1097 | |

| Organ space SSI | 3 (0.2) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0.0033 | |

| Preoperative/intraoperative urine culture | |||||

| No bacterial growth | 791 (52.9) | 82 (50.0) | 709 (53.3) | 0.4290 | |

| Bacterial growth, not UTI | 111 (7.4) | 14 (8.5) | 97 (7.3) | 0.5650 | |

| Bacterial growth, UTI | 76 (5.1) | 10 (6.1) | 66 (5.0) | 0.5311 | |

| Postoperative outcomes | |||||

| Postoperative UTI | 48 (3.2) | 23 (14.0) | 25 (1.9) | < 0.0001 | |

| Postoperative sepsis | 9 (0.6) | 6 (3.7) | 3 (0.2) | < 0.0001 | |

| Postoperative septic shock | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0.7256 | |

| Readmission | 75 (5.0) | 52 (31.7) | 23 (1.7) | < 0.0001 | |

| Progressive renal insufficiency | 5 (0.3) | 2 (1.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0.0375 | |

| Unplanned reoperation | 23 (1.5) | 12 (7.3) | 11 (0.8) | < 0.0001 | |

| Blood transfusion | 4 (0.3) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0.0124 | |

| Ureteral stent/catheter | 752 (50.3) | 95 (57.9) | 657 (49.4) | 0.1410 | |

| Unplanned procedure related to anti-reflux procedure | 36 (2.4) | 22 (13.4) | 14 (1.1) | < 0.0001 | |

| Unplanned urinary catheter (Intermittent or Indwelling) | 45 (3.0) | 29 (17.7) | 16 (1.2) | < 0.0001 | |

On multivariate analysis (OR, 95%CI, P value), postoperative UTIs (6.39, 2.83-12.4, P < 0.01) and superficial SSIs (12.3, 1.48-107, 0.02) were found to be predictive, as were unplanned procedures (5.73, 2.15-15.3, < 0.01) and catheterization (8.81, 3.90-20.0, < 0.01). No association was found between returning to the ED and postoperative sepsis, organ space SSI, renal insufficiency, or blood transfusion. While cardiac risk factors were also no longer associated with ED visits, being born prematurely was, specifically at 35-36 weeks (2.75, 1.39-5.18, 0.01) (Table 4).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value1 | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1.06 (0.65-1.66) | 0.818 | 1.18 (0.69-1.92) | 0.529 |

| Structural pulmonary abnormalities | 2.33 (0.92-5.20) | 0.052 | 2.60 (0.86-6.96) | 0.087 |

| Esophageal/gastric/intestinal disease | 1.93 (1.04-3.38) | 0.028 | 1.12 (0.46-2.52) | 0.793 |

| Ostomy | 1.89 (0.97-3.42) | 0.046 | 0.94 (0.36-2.22) | 0.890 |

| Postoperative variables and outcomes | ||||

| Length of stay ≥ 20 days | 4.05 (0.19-42.43) | 0.254 | 1.87 (0.05-34.8) | 0.704 |

| Operative time ≥ 167 minutes | 1.51 (1.09-2.09) | 0.013 | 1.19 (0.82-1.71) | 0.362 |

| Postoperative urinary tract infection | 8.52 (4.69-15.4) | <0.001 | 6.10 (2.93-12.4) | < 0.001 |

| Postoperative sepsis | 16.81 (4.39-80.3) | <0.001 | 3.28 (0.39-33.0) | 0.272 |

| Superficial incisional surgical site infection | 12.38 (2.04-94.5) | 0.006 | 12.3 (1.48-107) | 0.022 |

| Organ space surgical site infection | 16.42 (1.56-355) | 0.023 | 1.56 (0.06-58.3) | 0.788 |

| Progressive renal insufficiency | 5.47 (0.72-33.2) | 0.064 | 0.92 (0.06-11.4) | 0.948 |

| Blood transfusion | 8.20 (0.98-68.8) | 0.036 | 3.19 (0.13-214) | 0.500 |

| Unplanned procedure related to anti-reflux procedure | 14.6 (7.37-29.8) | < 0.001 | 5.73 (2.15-15.3) | < 0.001 |

| Unplanned urinary catheter (intermittent or indwelling) | 17.7 (9.47-15.1) | < 0.001 | 8.81 (3.90-20.0) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac risk factors | 0.153 | 0.107 | ||

| None | Referent | Referent | ||

| Minor | 2.34 (1.08-4.63) | 0.021 | 1.57 (0.59-3.69) | 0.333 |

| Major | 1.08 (0.37-2.54) | 0.876 | 0.25 (0.05-0.98) | 0.070 |

| Prematurity | 0.003 | 0.023 | ||

| Full-term | Referent | Referent | ||

| 25-30 completed weeks gestation | 0.63 (0.03-3.18) | 0.660 | 0.32 (0.02-2.00) | 0.317 |

| 31-34 completed weeks gestation | 1.61 (0.60-3.65) | 0.292 | 1.21 (0.36-3.26) | 0.734 |

| 35-36 completed weeks gestation | 3.07 (1.70-5.30) | < 0.001 | 2.75 (1.39-5.18) | 0.002 |

This study aimed to identify patient factors associated with subsequent ED visits within the acute post-UNC period. Of the total cohort, 11.0% visited the ED post-UNC. We found that postoperative UTIs increased the odds of returning to the ED within the 30-day postoperative period by 6.4 times compared to those without a UTI. Unfortunately, UTIs may occur postoperatively in an otherwise successful UNC procedure. Despite preemptive antibiotics and antiseptic measures taken perioperatively, presumed UTIs remain one of the most common reasons for return after pediatric urologic procedures[5]. In one retrospective review of 398 patients who underwent UNC, 27.2% developed a postoperative UTI, with contributing factors such as female gender, breakthrough infections, and the presence of voiding dysfunction[6]. Factors such as bacterial colonization during catheterization, incomplete bladder emptying, or pre-existing urologic abnormalities may explain some of the underlying biological mechanisms that increase the baseline risk of infection in such patients. Superficial SSIs were also associated with a higher likelihood of leading to a postoperative ED visit, although still a rare event overall, occurring in only 1.8% of patients included in the current analysis. Further investigation is needed into perioperative protocols, catheterization practices, and pre-existing urologic abnormalities to better understand the etiology of these infections.

Unplanned catheterization following UNC was another independent variable associated with an increased risk of ED return. A well-known risk of indwelling catheters is the development of catheter-associated UTIs, which alone could warrant visiting the ED, as previously mentioned[7]. It should also be acknowledged that catheterization following UNC could have been performed secondary to an unanticipated surgical complication, such as urinary retention. Such difficulties may appear resolved after initial catheterization, prompting discharge home, only to return or worsen once out of the hospital[8,9]. Additionally, patients sent home with an indwelling catheter can serve as a stressor for families and prompt return, particularly if painful or believed to be malfunctioning. Performing catheter-less UNC or removing it as soon as possible may be warranted. One retrospective study has found that catheter-less UNC reduced length of stay, rates of readmission, and the amount of postoperative medication needed without worsening complication rates[10]. However, it's important to note that these strategies are not universally adopted, and further research is needed to assess their feasibility and efficacy across diverse clinical settings. Implementing catheterization-free protocols requires careful patient selection and adherence to surgical best practices to ensure optimal outcomes. Clinicians should weigh the potential benefits against the risks and consider individual patient factors when deciding on the use of catheterization in UNC procedures.

While previous studies on UNC most always include the patients’ ages at the time of surgery, few include premature birth status as a possible risk factor in postoperative outcomes[2,6,11]. Premature birth status at 35-36 weeks of gestation was found to increase the likelihood of returning to ED postoperatively. However, children born between 25 and 34 weeks were not more likely to have a postoperative ED visit compared to their full-term counterparts. Multiple factors could explain this discrepancy. One hypothesis for why more premature infants were not more likely to return could be explained by the expected standard of care. With preterm neonates being a high-risk patient category, postoperative care may be more comprehensive, and greater caution is taken before sending them home. Increased parental instructions and education are also likely given to those born extremely preterm, thus helping to prevent ED visits.

The study leverages one of the largest, most up-to-date national databases for pediatric surgery, providing robust data for analysis. However, limitations similar to other retrospective, database-driven studies apply. The data may not fully represent the entire population, as the majority of reporting hospitals are large academic institutions, potentially leading to selection bias. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to smaller or non-academic settings. While machine learning was used to minimize subjective bias in the selection of independent variables for multivariable logistic regression, the potential for residual confounding remains. This could affect the accuracy of the identified risk factors, particularly if unmeasured variables influenced the outcomes. Furthermore, the reliance on retrospective data prevents establishing causal relationships between identified variables and postoperative ED visits.

To mitigate these limitations, future research could incorporate data from a broader range of healthcare settings, including community hospitals, to improve representativeness. Prospective studies are also needed to validate these findings and explore causal mechanisms. Additionally, integrating more granular clinical data, such as socioeconomic factors or detailed perioperative variables, not captured by NSQIP, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of modifiable risk factors. Despite these constraints, this study provides valuable insights into potentially modifiable risk factors for postoperative ED visits following pediatric surgical interventions, particularly given the low volume of UNCs performed annually at the national level.

Postoperative infections, unplanned procedures, and prematurity are primary factors contributing to ED visits within the immediate postoperative period after ureteral reimplantation. Additional studies are needed to determine if replicable contributing factors are found concerning ED visits after other anti-reflux procedures.

| 1. | Pohl HG, Joyce GF, Wise M, Cilento BG Jr. Vesicoureteral reflux and ureteroceles. J Urol. 2007;177:1659-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang HH, Tejwani R, Cannon GM Jr, Gargollo PC, Wiener JS, Routh JC. Open versus minimally invasive ureteroneocystostomy: A population-level analysis. J Pediatr Urol. 2016;12:232.e1-232.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pompeo A, Molina WR, Sehrt D, Tobias-Machado M, Mariano Costa RM, Pompeo AC, Kim FJ. Laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy for ureteral injuries after hysterectomy. JSLS. 2013;17:121-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wallace A, Rodriguez MV, Gundeti MS. Postoperative course following complex major pediatric urologic surgery: A single surgeon experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:2120-2124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Naoum NK, Chua ME, Ming JM, Santos JD, Saunders MA, Lopes RI, Koyle MA, Farhat WA. Return to emergency department after pediatric urology procedures. J Pediatr Urol. 2019;15:42.e1-42.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dogan HS, Bozaci AC, Ozdemir B, Tonyali S, Tekgul S. Ureteroneocystostomy in primary vesicoureteral reflux: critical retrospective analysis of factors affecting the postoperative urinary tract infection rates. Int Braz J Urol. 2014;40:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Flores-Mireles A, Hreha TN, Hunstad DA. Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2019;25:228-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Esposito C, Varlet F, Riquelme MA, Fourcade L, Valla JS, Ballouhey Q, Scalabre A, Escolino M. Postoperative bladder dysfunction and outcomes after minimally invasive extravesical ureteric reimplantation in children using a laparoscopic and a robot-assisted approach: results of a multicentre international survey. BJU Int. 2019;124:820-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lipski BA, Mitchell ME, Burns MW. Voiding dysfunction after bilateral bladder extramural ureteral reimplantation. J Urol. 1998;159:1019-1021. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Duong DT, Parekh DJ, Pope JC 4th, Adams MC, Brock JW 3rd. Ureteroneocystostomy without urethral catheterization shortens hospital stay without compromising postoperative success. J Urol. 2003;170:1570-3; discussion 1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang HS, Tejwani R, Wolf S, Wiener JS, Routh JC. Readmissions, unplanned emergency room visits, and surgical retreatment rates after anti-reflux procedures. J Pediatr Urol. 2017;13:507.e1-507.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |