Published online Mar 9, 2024. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v13.i1.89201

Peer-review started: October 24, 2023

First decision: November 30, 2023

Revised: December 1, 2023

Accepted: December 19, 2023

Article in press: December 19, 2023

Published online: March 9, 2024

Processing time: 134 Days and 16.1 Hours

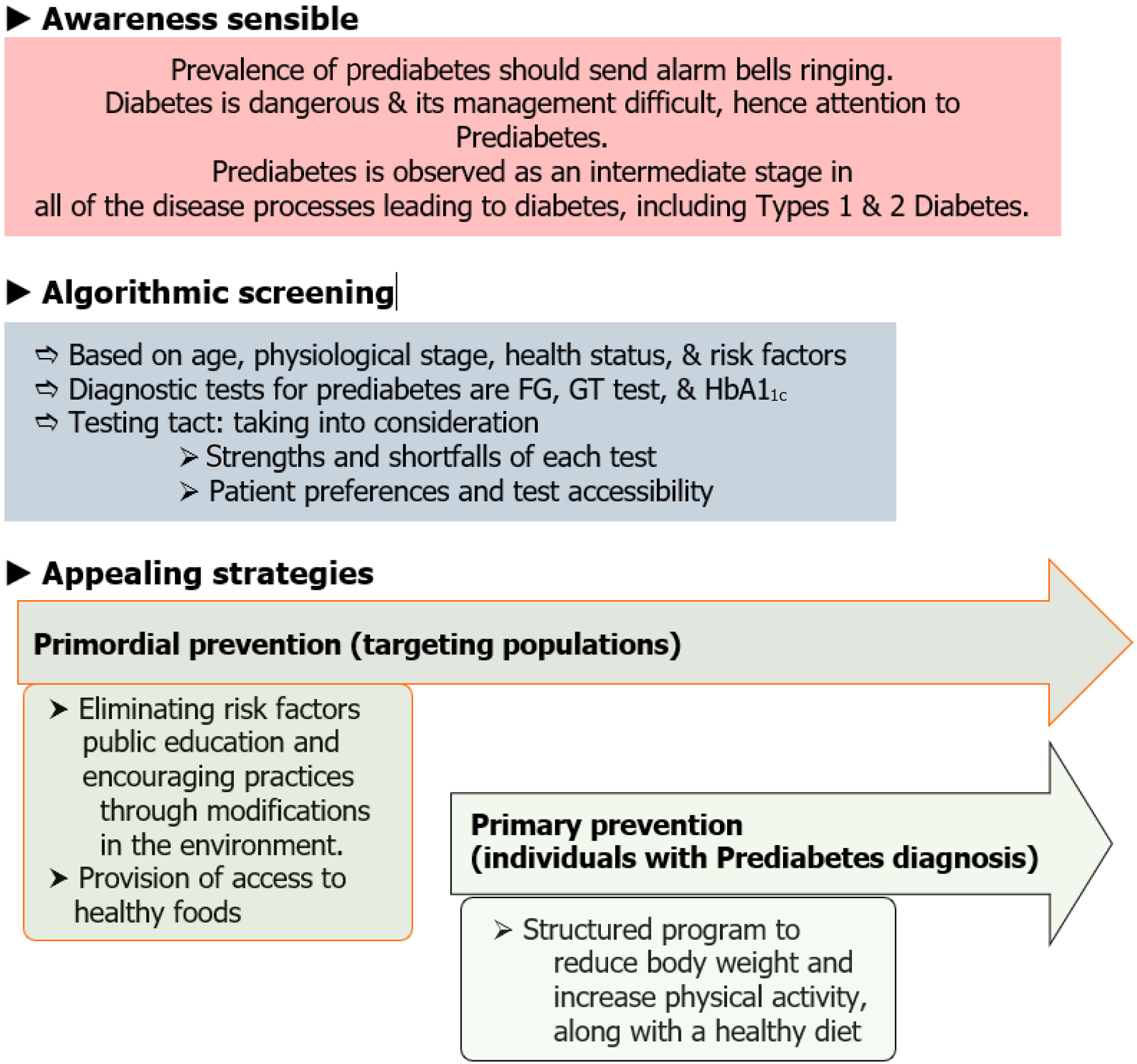

Diabetes is a devastating public health problem. Prediabetes is an intermediate stage in the disease processes leading to diabetes, including types 1 and 2 diabetes. In the article “Prediabetes in children and adolescents: An updated review,” the authors presented current evidence. We simplify and systematically clearly present the evidence and rationale for a conceptual framework we term the ‘3ASs’: (1) Awareness Sensible; (2) Algorithm Simple; and (3) Appealing Strategies. Policy makers and the public need to be alerted. The prevalence of prediabetes should send alarm bells ringing for parents, individuals, clinicians, and policy makers. Prediabetes is defined by the following criteria: impaired fasting glucose (100-125 mg/dL); impaired glucose tolerance (2 h postprandial glucose 140-199 mg/dL); or hemoglobin A1c values of 5.7%–6.4%. Any of the above positive test alerts for intervention. Clinical guidelines do not recommend prioritizing one test over the others for evaluation. Decisions should be made on the strengths and shortfalls of each test. Patient preferences and test accessibility should be taken into consideration. An algorithm based on age, physiological stage, health status, and risk factors is provided. Primordial prevention targeting populations aims to eliminate risk factors through public education and encouraging practices through environmental modifications. Access to healthy foods is provided. Primary prevention is for individuals with a prediabetes diagnosis and involves a structured program to reduce body weight and increase physical activity along with a healthy diet. An overall methodical move to a healthy lifestyle for lifelong health is urgently needed. Early energetic prediabetes action is necessary.

Core Tip: Prediabetes provides a window for preventive action. The prevalence of prediabetes should send alarm bells ringing for parents, individuals, clinicians, and policy makers. Algorithms should delineate based on age, physiological stage, health status, and risk factors. Diabetes is dangerous and its management is difficult; hence, attention on prediabetes, which provides early opportunity for health promotion and prevention. Primordial prevention should target at-risk populations and primary prevention should target individuals for healthy lifestyles. Doctors should be proficient in modern technologies proficient to optimize prevention strategies.

- Citation: Jain S. ‘Prediabetes’ as a practical distinctive window for workable fruitful wonders: Prevention and progression alert as advanced professionalism. World J Clin Pediatr 2024; 13(1): 89201

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v13/i1/89201.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v13.i1.89201

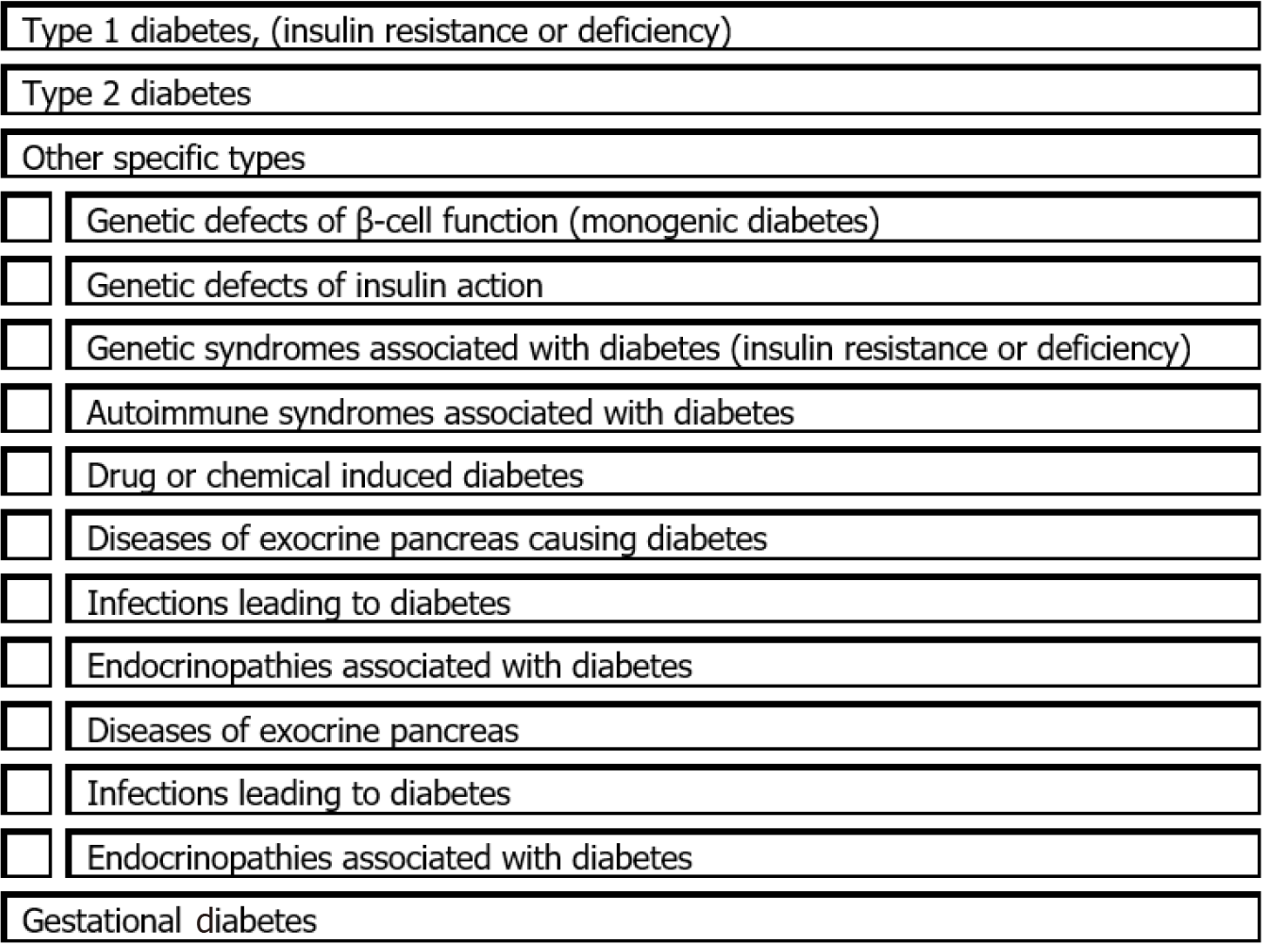

Obesity is a global public health crisis. Prevalence rates are increasing among children and adolescents. Prediabetes identifies individuals at high risk of developing diabetes[1]. Prediabetes provides a preventive action window against progression and is considered an intermediate stage in all the disease processes leading to diabetes. The expanded list of diabetes etiologies is shown in Figure 1. All entities need necessary attention, particularly in prevention with increased efforts on identifying and acting on prediabetes.

“Discoveries many!

Necessitating strategies novel;

Innovative & inspiring”.

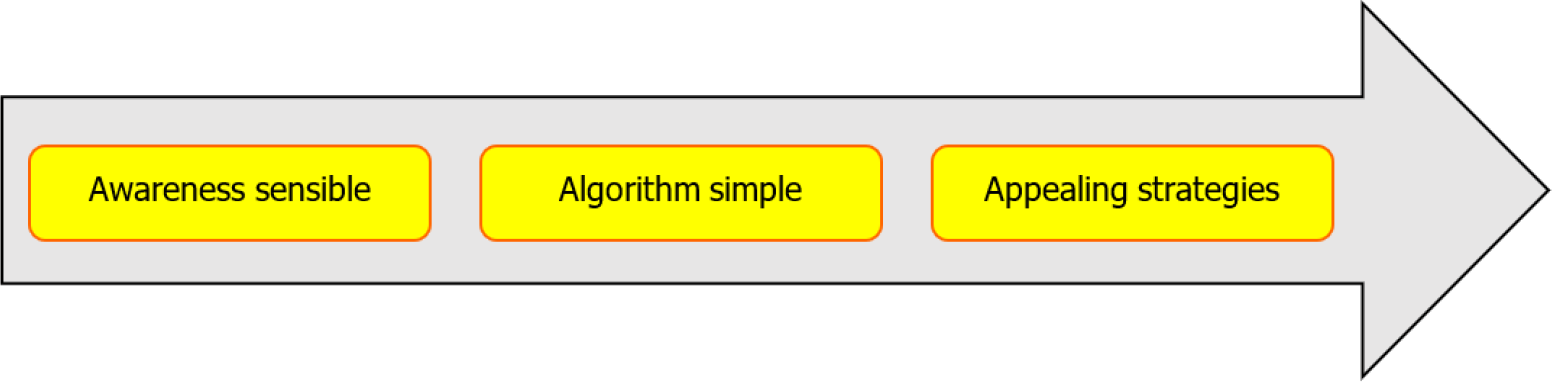

In the article “Prediabetes in children and adolescents: An updated review” Ng et al[2] comprehensively present current evidence. They aim to provide pediatricians and primary care providers with an updated overview of this important condition. A clear understanding of the condition is essential for success with advancements professionally presented. Policy makers and the public need to be alerted and apprised. A simplified conceptual framework is presented as the ‘3ASs’ in Figure 2.

As many as 34% or 88 million United States adults have prediabetes, as per the most recent estimate (2020) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[3]. Children are likely to be similarly affected considering the increasing rate of obesity. Ng et al[2] reported a pooled prevalence of up to 8.84% from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis[2,4]. This increasing prevalence should send alarm bells ringing for parents, individuals, clinicians, and policy makers.

‘Alarming statistics necessitate advanced strategies’.

Prediabetes is defined by the following criteria: Impaired Fasting Glucose (IFG) (100-125 mg/dL [5.6-6.9 mmol/L]), OR: Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) (2 h postprandial glucose 140-199 mg/dL [7.8-11 mmol/L]), OR: Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values of 5.7%–6.4% (39-47 mmol/moL)[5].

Suspicions of prediabetes induce actions, and tests advance the actions to restore healthy status. Any of the above positive test alerts practitioners that intervention is necessary. Clear concepts are necessary for practitioners, and this should provide the impetus to the Core tip given by Ng et al[2] “child health practitioners are struggling with the definition”.

‘Knowing, understanding, & knack,

Testing, numbers, & tact’.

Evidence needs to be expertly incorporated into algorithms. We present an algorithm based on American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee recommendations (Figure 2)[6]. An algorithm based on age, physiological stage, health status, and risk factors is best.

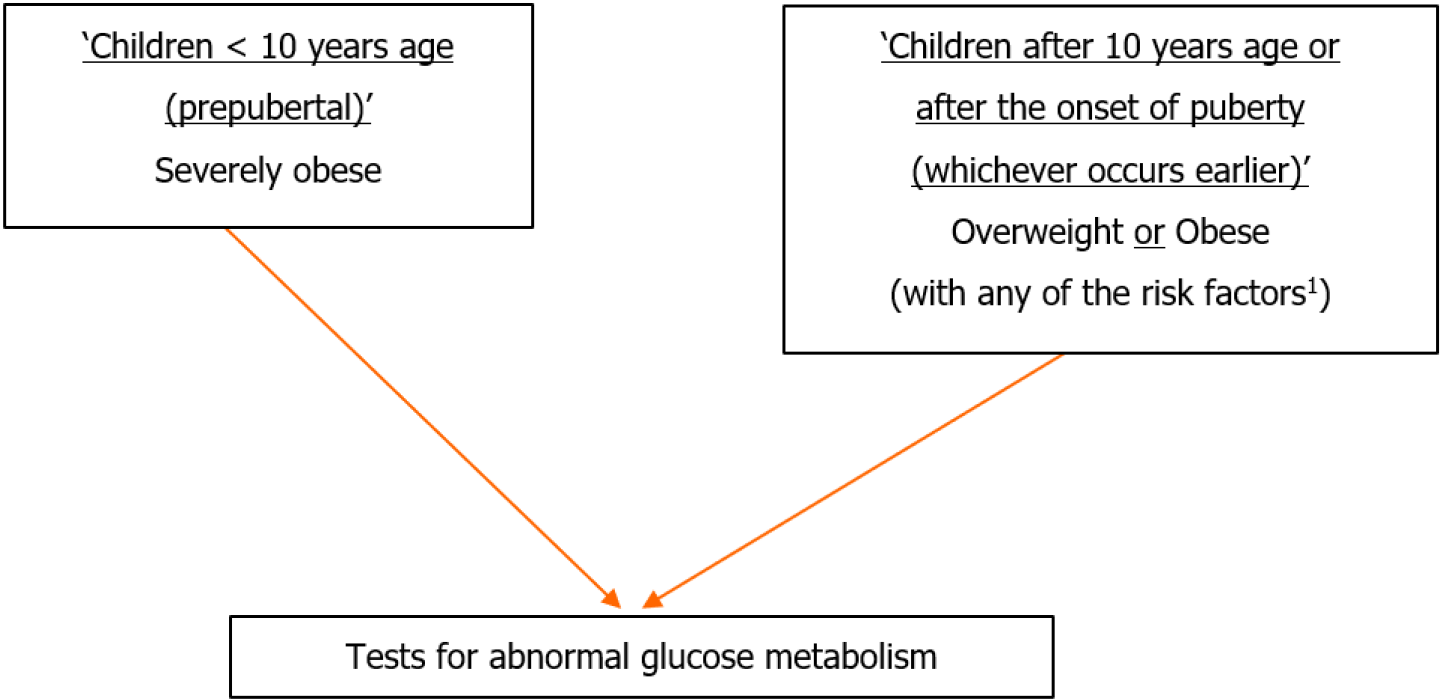

The current comprehensive evidence is that: (1) 1 in 5 United States adolescents with obesity have prediabetes[7,8]; (2) The comorbidities of pediatric overweight and obesity are that prediabetes and diabetes occur more frequently among children ≥ 10 years of age, are in early pubertal stages, or have a family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)[8]; (3) The risk profile for diabetes mellitus and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children < 10 years of age is lower (especially in the absence of severe obesity). Hence, obtaining tests for abnormal glucose metabolism or liver function is not universally recommended for these children[8]; (4) Prediabetes is often associated with insulin resistance syndrome (also known as metabolic syndrome), which has dyslipidemia of the high-triglyceride or low- or high-density lipoprotein type, or both, and hypertension[5]; and (5) Progression of IFG to overt T2DM appears to be lower in the pediatric obese population than in adults[9]. However, the transition from IGT to T2DM is more rapid in children and adolescents than adults[10].

To encourage a pragmatic and efficient evaluation strategy (avoiding repeated testing), it is recommended that in children with obesity, evaluation for lipid abnormalities, abnormal glucose metabolism, and liver dysfunction be performed at the same time, beginning at 10-years-old[8].

Diagnostic tests for prediabetes are Fasting Glucose, Glucose Tolerance test, and HbA1c. Clinical guidelines do not recommend preferring one test over the other for evaluation. Practitioners need to know and understand the strengths and shortfalls of each test for judicious use. Patient preferences and test accessibility should be taken into consideration[8].

In view of these, we recommend the following tests for abnormal glucose metabolism and discuss significance: (1) IFG: > 99 mg/dL (5.5 mmol/L) is the upper limit of normal, and alerts action because when left uncontrolled, it causes a progressively greater risk for the development of microvascular and macrovascular complications[5]; (2) IGT: Hyperglycemia when challenged with the oral glucose load, necessitates strict dietary measures, and adherence is improved when coupled with counselling; and (3) HbA1c: The HbA1c test is easy to obtain as it can be done anytime and fasting is not required. This provides stronger and more specific associations with cardiometabolic risk[11] (Figure 3).

Further, Ng et al[2] have provided a simplified approach algorithm, which leads with risk factors. One size does not fit all, especially in the growing pediatric age group. Ng et al's[2] algorithm proposes oral glucose tolerance test or fasting plasma glucose, +/- HbA1C. Based on the definition above that states that any one positive test of the ‘Tests for abnormal glucose metabolism’ is sufficient to diagnose prediabetes, it is unclear what happens in the following situations: (1) Whether an IGT test will be performed in ‘severely obese’ children < 10-years-old when there are no risk factors and FBG is normal. Their algorithm suggests that the test should be performed only if risk factors are present. It should be performed, as (i) Individuals with IFG often manifest hyperglycemia only with the oral glucose load challenge, as in the standardized oral glucose tolerance test. Results will motivate a prevention rationale because (ii) subjects with both IFG and IGT have dangers of additive metabolic defects and are more likely to progress to overt T2DM[10]. Furthermore, should IGT be performed on overweight only patients with a positive IFG? No, as unnecessary testing is burdensome for individuals and healthcare institutions. Further, many individuals with IFG are euglycemic in their daily lives and may have normal or nearly normal HbA1c levels[5]. Thus, they have healthy diets, do not binge eat, and even if binging, their body is taking care of sugar levels. Lifestyle interventions for ideal weight should suffice, rewardingly!

‘Simple choices – comprehensive success’.

Diabetes is dangerous, and its management can be difficult for good glucose control and complication prevention. Prediabetes provides an early opportunity for health promotion and prevention. Hence the need for energetic strategies with appeal that ensure success.

‘Methods scientific, Motivation strong,

Success major over morbidity & mortality’.

Ng et al[2] write that “The lack of prospective long-term longitudinal data to inform evidence-based practice for disease prevention and complication avoidance is the real challenge and major gap in pediatric prediabetic research”[2]. Waiting for evidence is unpardonable. The Diabetes Prevention Program strikingly showed that lifestyle or drug intervention intensified in individuals with IGT prevents or delays the onset of T2DM[12]. Similar beneficial effects in obese adolescents with IGT are likely[5]! Such benefits necessitate large scale strategies for more benefits for many. The provision by Ng et al[2] of only individualistic strategies needs further expansion[2].

Prevention is most beneficial if it is early and energetic. Given the rising burden of lifestyle diseases and associated risks, we outline succinct strategies as appealing advancements: (1) Primordial prevention: Targeting an entire population is important, and this focusses on social and environmental conditions[13]. This aims at eliminating risk factors in general populations through public education and encouraging practice through modifications in the environment. Access to healthy foods is provided[1]. Breastfeeding should be encouraged and ensured, as it is associated with protection against childhood overweight and diabetes[14]. In mothers with gestational diabetes, breastfeeding protects against obesity and T2DM[15,16]. A sedentary lifestyle is to be avoided and the advice should be to be physically active for at least 60 min per day every day[17]; (2) Primary prevention: Interventions aiming at ameliorating risk factors reward favorably. Individuals with a prediabetes diagnosis should be promptly referred to a structured program for reducing body weight and increasing physical activity. A healthy meal plan is provided and intensive encouragement provided for compliance.

Appeal is ensured by education of long-term health burdens, which culminate in decreased life-expectancy. Health benefits of lifestyle modification are emphasized.

Attractiveness and compliance need to be ensured with motivational methods like health education and inspirational encouragement – ‘healthy lifestyle favorable & must for lifelong happiness’.

In a recent Systematic Review, the benefits of using new information and communications technologies for improving health and preventing obesity were highlighted, with improvements in knowledge for nutrition habits and promotion of physical activity[18]. Therefore, doctors should be educated to be proficient in new technology use[19].

Ng et al[2] highlighted the use of metformin as a second-line management in individuals refractory to lifestyle interventions[2,20]. However, a recent systemic review was inconclusive as to the benefits of metformin to prevent the progression to overt T2DM in children and adolescents with prediabetes[21]. Hence, the focus should be on the continuation of lifestyle interventions.

Important points for professional impact are summarized in Figure 4.

In summary, the message is that if left unattended, the high incidence and higher risks of prediabetes will require the highest level of major comprehensive professionalism. Patients transition to a healthy lifestyle for lifelong health needs practitioner attention and advancement.

“Progress for health, contemporarily, future favorable completely;

Prediabetes alerting professional tact timely;

Energetic and rationale, ensuring lifelong smiles surely”.

The author is thankful to authors of all the references quoted for all of the interesting insights into advancing care of children.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Indian Academy Pediatrics, Elected Life Member No. L/2000/J-457; Indian Pediatric Nephrology Group, Life Membership No. L/99/S-33.

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Galanakis C, Greece S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, Garber AJ, Hurley DL, Jastreboff AM, Nadolsky K, Pessah-Pollack R, Plodkowski R; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. American association of clinical endocrinologists and american college of endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22 Suppl 3:1-203. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Ng HY, Chan LTW. Prediabetes in children and adolescents: An updated review. World J Clin Pediatr. 2023;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Powers AC, Niswender KD, Evans-Molina C. Diabetes Mellitus: Diagnosis, Classification, and Pathophysiology In: Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo D, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 21st ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2022. p 3094-3103. |

| 4. | Han C, Song Q, Ren Y, Chen X, Jiang X, Hu D. Global prevalence of prediabetes in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes. 2022;14:434-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Weber DR, Jospe N. Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme III JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, Behrman RE. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2019: 654-680. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:S17-S38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 1413] [Article Influence: 471.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Andes LJ, Cheng YJ, Rolka DB, Gregg EW, Imperatore G. Prevalence of Prediabetes Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States, 2005-2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:e194498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, Avila Edwards KC, Eneli I, Hamre R, Joseph MM, Lunsford D, Mendonca E, Michalsky MP, Mirza N, Ochoa ER, Sharifi M, Staiano AE, Weedn AE, Flinn SK, Lindros J, Okechukwu K. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity. Pediatrics. 2023;151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 237.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hagman E, Danielsson P, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Marcus C. Association between impaired fasting glycaemia in pediatric obesity and type 2 diabetes in young adulthood. Nutr Diabetes. 2016;6:e227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Weiss R, Taksali SE, Tamborlane WV, Burgert TS, Savoye M, Caprio S. Predictors of changes in glucose tolerance status in obese youth. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:902-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wallace AS, Wang D, Shin JI, Selvin E. Screening and Diagnosis of Prediabetes and Diabetes in US Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2020;146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13206] [Cited by in RCA: 12422] [Article Influence: 540.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Sakuta M. [One hundred books which built up neurology (37)-Charcot JM "Leçons sur les Localsations das les Maladies du Cerveau et de la Moelle Epinière faites a la Faculté de Médecine de Paris"(1876-1880)]. Brain Nerve. 2010;62:90-91. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Jain S, Thapar RK, Gupta RK. Complete coverage and covering completely: Breast feeding and complementary feeding: Knowledge, attitude, and practices of mothers. Med J Armed Forces India. 2018;74:28-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jain S, Kushwaha AS. Complete coverage & covering completely: Able, Bold, & Confident mothers, Sustainable Development Goals & Medical Education. Selected Topics on Infant Feeding. 2022; IntechOpen Ltd. London. p 1-18. PRINT ISBN: 978-1-80355-789-2, EBOOK (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-80355-791-5. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/81682. |

| 16. | Elbeltagi R, Al-Beltagi M, Saeed NK, Bediwy AS. Cardiometabolic effects of breastfeeding on infants of diabetic mothers. World J Diabetes. 2023;14:617-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jain S, Thapar RK. Life's crucial transition and leads for comprehensive trajectory: Adolescents survey at physiological stages for prudent policies and refinements for practice. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:4648-4655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Navidad L, Padial-Ruz R, González MC. Nutrition, Physical Activity, and New Technology Programs on Obesity Prevention in Primary Education: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jain S, Jain BK, Jain PK, Marwaha V. "Technology Proficiency" in Medical Education: Worthiness for Worldwide Wonderful Competency and Sophistication. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2022;13:1497-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hosey CM, Halpin K, Yan Y. Considering metformin as a second-line treatment for children and adolescents with prediabetes. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2022;35:727-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Masarwa R, Brunetti VC, Aloe S, Henderson M, Platt RW, Filion KB. Efficacy and Safety of Metformin for Obesity: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2021;147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |