Published online Mar 9, 2024. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v13.i1.89139

Peer-review started: October 21, 2023

First decision: December 15, 2023

Revised: December 29, 2023

Accepted: February 18, 2024

Article in press: February 18, 2024

Published online: March 9, 2024

Processing time: 137 Days and 8.4 Hours

Undernutrition is a crucial cause of morbidity and mortality among children in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs). A better understanding of maternal general healthy nutrition knowledge, as well as misbeliefs, is highly essential, especially in such settings. In the current era of infodemics, it is very strenuous for mothers to select not only the right source for maternal nutrition information but the correct information as well.

To assess maternal healthy nutritional knowledge and nutrition-related misbeliefs and misinformation in an LMIC, and to determine the sources of such information and their assessment methods.

This cross-sectional analytical observational study enrolled 5148 randomly selected Egyptian mothers who had one or more children less than 15 years old. The data were collected through online questionnaire forms: One was for the general nutrition knowledge assessment, and the other was for the nutritional myth score. Sources of information and ways of evaluating internet sources using the Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose test were additionally analyzed.

The mean general nutrition knowledge score was 29 ± 9, with a percent score of 70.8% ± 12.1% (total score: 41). The median myth score was 9 (interquartile range: 6, 12; total score: 18). The primary sources of nutrition knowledge for the enrolled mothers were social media platforms (55%). Half of the mothers managed information for currency and authority, except for considering the author's contact information. More than 60% regularly checked information for accuracy and purpose. The mothers with significant nutrition knowledge checked periodically for the author's contact information (P = 0.012). The nutrition myth score was significantly lower among mothers who periodically checked the evidence of the information (P = 0.016). Mothers dependent on their healthcare providers as the primary source of their general nutritional knowledge were less likely to hold myths by 13% (P = 0.044). However, using social media increased the likelihood of having myths among mothers by approximately 1.2 (P = 0.001).

Social media platforms were found to be the primary source of maternal nutrition information in the current era of infodemics. However, healthcare providers were the only source for decreasing the incidence of maternal myths among the surveyed mothers.

Core Tip: Undernutrition is one of the principal causes of morbidity and mortality in children in low- or middle-income countries. The evaluation of maternal nutrition knowledge scores is crucial to improving practice. The infodemic era has significantly impacted the changing sources of nutrition information and myths. Consequently, this study aimed to assess healthy nutritional knowledge and nutrition-related misinformation and misbeliefs among a significant sample of Egyptian mothers. In addition, other objectives included determining the sources of nutritional information and how those mothers manage the sources of nutritional-related knowledge.

- Citation: Zein MM, Arafa N, El-Shabrawi MHF, El-Koofy NM. Effect of nutrition-related infodemics and social media on maternal experience: A nationwide survey in a low/middle income country. World J Clin Pediatr 2024; 13(1): 89139

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v13/i1/89139.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v13.i1.89139

Undernutrition is one of the salient causes of morbidity and mortality among children less than five years old in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs)[1]. Accordingly, proper and adequate nutrition is vital for normal child's growth and development and prevention of long-term morbidity and subsequent mortality. Different previously published data support the effectiveness of variable nutritional interventions in improving the nutritional status of children and reducing mortality[2,3].

Mothers are the primary care providers for their children in all household affairs, especially nutrition[4]. Therefore, the level of maternal general nutritional knowledge usually impacts their nutrition behavior and practice[5]. Consequently, evaluation of maternal health understanding is crucial to filling the gap in training. This will help identify the most deficient points in this community's upcoming nutrition education programs. In addition to parental nutrition knowledge, nutrition myth is another essential factor previously reported in the literature as a determinant factor affecting their feeding style[6].

The phenomenon of infodemics refers to the abundant and widespread dissemination of information, whether accurate or not, through different media platforms, including mass media, social media, and online forums[7]. It can be challenging for mothers to select the correct information from the flow of sources. Different sources of nutrition education are available in this current era of infodemics, such as healthcare providers, family members, mass media, and social media. The sources of nutrition education, with the advent of internet technology and smartphones, have become much more diverse[8]. Despite the fact that this technology facilitates the delivery of information, acquiring the right information at the right time in the appropriate form is of greater importance[9].

To the researchers' knowledge, this is the first published study from Egypt evaluating this problem despite its significance in this LMIC.

This study's main objective was to assess healthy nutritional knowledge and nutrition-related misinformation and misbeliefs among a large sample of Egyptian mothers. In addition, this study aimed to determine the sources of nutritional information and how those mothers manage the sources of nutritional-related knowledge.

A cross-sectional analytical observational study.

A convenient sample (easy access).

A sample size of 5100 was calculated using a formula for survey sample size calculation[10]. Here's a breakdown: n represents the sample size; z signifies the z-score, which is approximately ± 2.58 for a 99% confidence interval (CI); p stands for the degree of variability (proportion of outcome). In this case, 81.2% of mothers were found to have a high to moderate level of nutritional knowledge in a study conducted in Bangladesh[11]; e denotes the level of precision, set at 1%; N refers to the study population size, which mainly consists of females, likely mothers of children under 15, constituting 32% of the Egyptian population aged 15 to 60 years, totaling 32 million[12].

The study population consisted of Egyptian mothers with one or more children (age of at least one child under 15 years). The participants were recruited from many governorates all over Egypt: The upper Egypt governorates included Giza, Fayoum, Menia, and Assiut; the lower Egypt governorates included Dakahlia, Gharbia, and Kafr El-Sheikh; Cairo and Alexandria.

A pre-tested e-questionnaire was used to collect data from the study participants. It included four sections: (1) Socio-demographic characteristics: Maternal, paternal, and siblings' age in years; sex of siblings; maternal and paternal education and occupation; residence; number of home bedrooms; and number of family members; (2) General nutrition knowledge questionnaire (GNKQ): It contains 41 questions that were derived from the validated general health questionnaire[13]. The questions of the original questionnaire were adapted to the Egyptian situation. Reliability analysis was conducted on the GNKQ, in which Cronbach's alpha was 0.73. Correct answers were coded with 1 and incorrect answers with 0. The total GNKQ score was 41. The percent score of the GNKQ was calculated, and the participants were categorized according to their responses into two groups: High to moderate knowledge (GNKQ percent score ≤ 70%) and low knowledge (GNKQ percent score > 70%)[14]; (3) Nutritional myths (misin

Data collection tool accuracy, validity, and reliability: A pre-test was performed to confirm the content validity of the questions and assure the validity of the results. In order to eliminate common mistakes and unclear wording and to ensure that the questions were understandable, a panel of 50 volunteers from various backgrounds reviewed the question construction. The final version of the questionnaire was updated to include the expert panel's comments. The questionnaires were distributed to the participants following this pilot study (the pilot results were not included in the final results). Reliability internal test (Cronbach’s) was done for the 18-item questionnaire (nutrition misinformation), where Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76 (high reliability).

Data collection technique: A Google form was created, and participants were invited through personal communication (via Facebook groups, WhatsApp contacts, and emails) with the researchers to complete and submit the form.

Statistical analysis: All the collected data were revised for completeness and logical consistency. The data were extracted from the Google form into the Microsoft Office Excel Software Program, 2019, and then analyzed in the Statistical Package of Social Science Software program, version 26 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) for statistical analyses.

Quantitative variables are described as the mean ± SD, median, minimum, and maximum and compared using an independent t-test and a Mann-Whitney U-test for two groups, with the level of statistical significance set at P < 0.05. Qualitative variables are described as frequencies and percentages. Moreover, qualitative variables were compared using the Chi-square and Fisher exact tests, with the level of statistical significance set at P < 0.05. A binary logistic regression model was used to determine which source of knowledge could predict the likelihood of holding myths and be more knowledgeable in nutrition.

The study protocol was approved by the scientific committee of the Public Health and Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University. It was approved by the International Ethical Committee at the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University (N 318-2023). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants after thoroughly explaining the study's aim and the importance of the online form before data collection. Only those who agreed were included, and those who refused were excluded from the study by submitting an empty form after answering "Not willing to participate." All procedures for data collection were treated with confidentiality according to the Helsinki Declarations of Biomedical Ethics. Participants were informed that this was an anonymous survey and participation was voluntary. The assessment did not involve any invasive procedures or induce any change in dietary patterns.

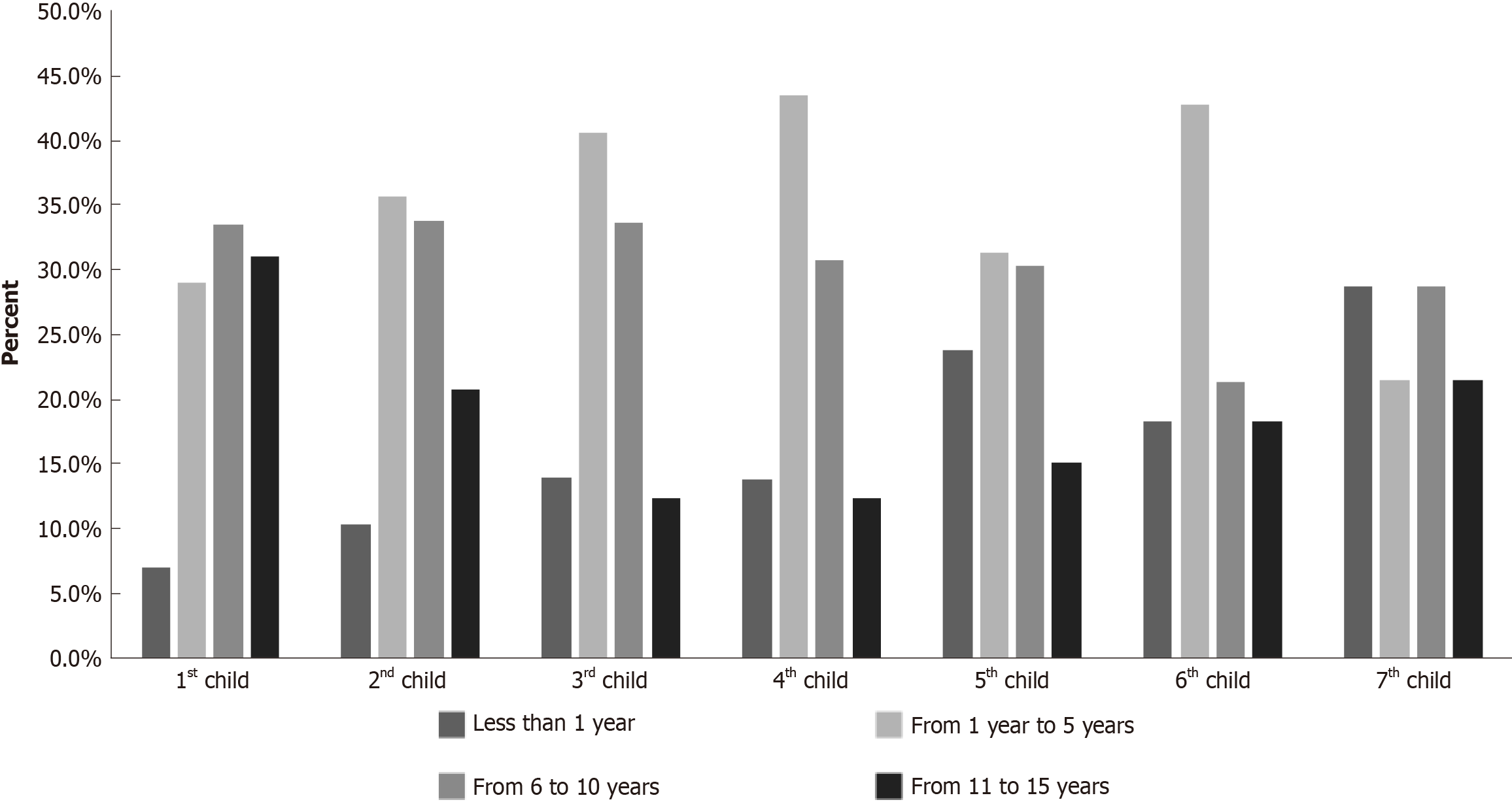

The response rate for the online form was 99.4%. There were 5148 responses from mothers with one or more children aged less than 15 years. The sociodemographic background information was collected and is illustrated in Table 1. It was found that more than half of the mothers (56.9%) and fathers (52.5%) were aged from 30 to 40 years; extreme age was found in 2.2% of mothers and 0.5% of fathers aged less than 20 years; 1.6% of mothers and 5.7% of fathers aged more than 50 years. Mothers and fathers had higher university grades at 59.1% and 65.1%, respectively. However, the number of mothers and fathers who could only read and write was 64 and 59, representing 1.2% and 1.1%, respectively. The number of working mothers was 3321 (64.5%), and 96.3% (5061) of fathers were working. Most families were from urban areas (81.6%) and had a house crowding index of two or less (94.8%). Most mothers had fewer than five children; 23.2%, 43.7%, 24.9%, and 6.5% of mothers had one, two, three, or four children, respectively. The questions were asked about the gender and age of the children (from one child to seven children). Their sex distribution was almost the same; 1–5 year age was more evident with the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th child (Figure 1). The total general nutrition knowledge score was 41. It was found that the mean available nutrition knowledge score was 29 ± 9, with a percent score of 70.8% ± 12.1%. The median score was 27 (interquartile range [IQR]: 27, 33), with a percent score of 73.2% (IQR: 65.9%, 80.5%). The nutrition myth question score was 18. The mean score was 9 ± 4, and the mean myth percent score was 50.9% ± 23.7%. The median myth score was 9 (IQR: 6, 12), and the median myth percent score was 50% (IQR: 33.3%, 66.7%).

| N | Percent | |

| Maternal age | ||

| Less than 20 yr | 115 | 2.2 |

| 20-yr | 1313 | 25.5 |

| 30-yr | 2931 | 56.9 |

| 40-yr | 708 | 13.8 |

| 50-yr | 81 | 1.6 |

| Paternal age | ||

| Less than 20 yr | 27 | 0.5 |

| 20-yr | 693 | 13.5 |

| 30-yr | 2704 | 52.5 |

| 40-yr | 1431 | 27.8 |

| 50-yr | 293 | 5.7 |

| Maternal education | ||

| Read and write | 64 | 1.2 |

| Primary school | 28 | 0.5 |

| Preparatory school | 91 | 1.8 |

| Secondary school | 441 | 8.6 |

| University | 3042 | 59.1 |

| Postgraduate | 1482 | 28.8 |

| Paternal education | ||

| Read and write | 59 | 1.1 |

| Primary school | 18 | 0.3 |

| Preparatory school | 63 | 1.2 |

| Secondary school | 433 | 8.4 |

| University | 3353 | 65.1 |

| Postgraduate | 1222 | 23.7 |

| Maternal occupation | ||

| Working | 3321 | 64.5 |

| Not working | 1827 | 35.5 |

| Paternal occupation | ||

| Working | 5061 | 98.3 |

| Not working | 87 | 1.7 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 4202 | 81.6 |

| Rural | 946 | 18.4 |

| Crowding index | ||

| ≤ 2 | 4878 | 94.8 |

| > 2 | 270 | 5.2 |

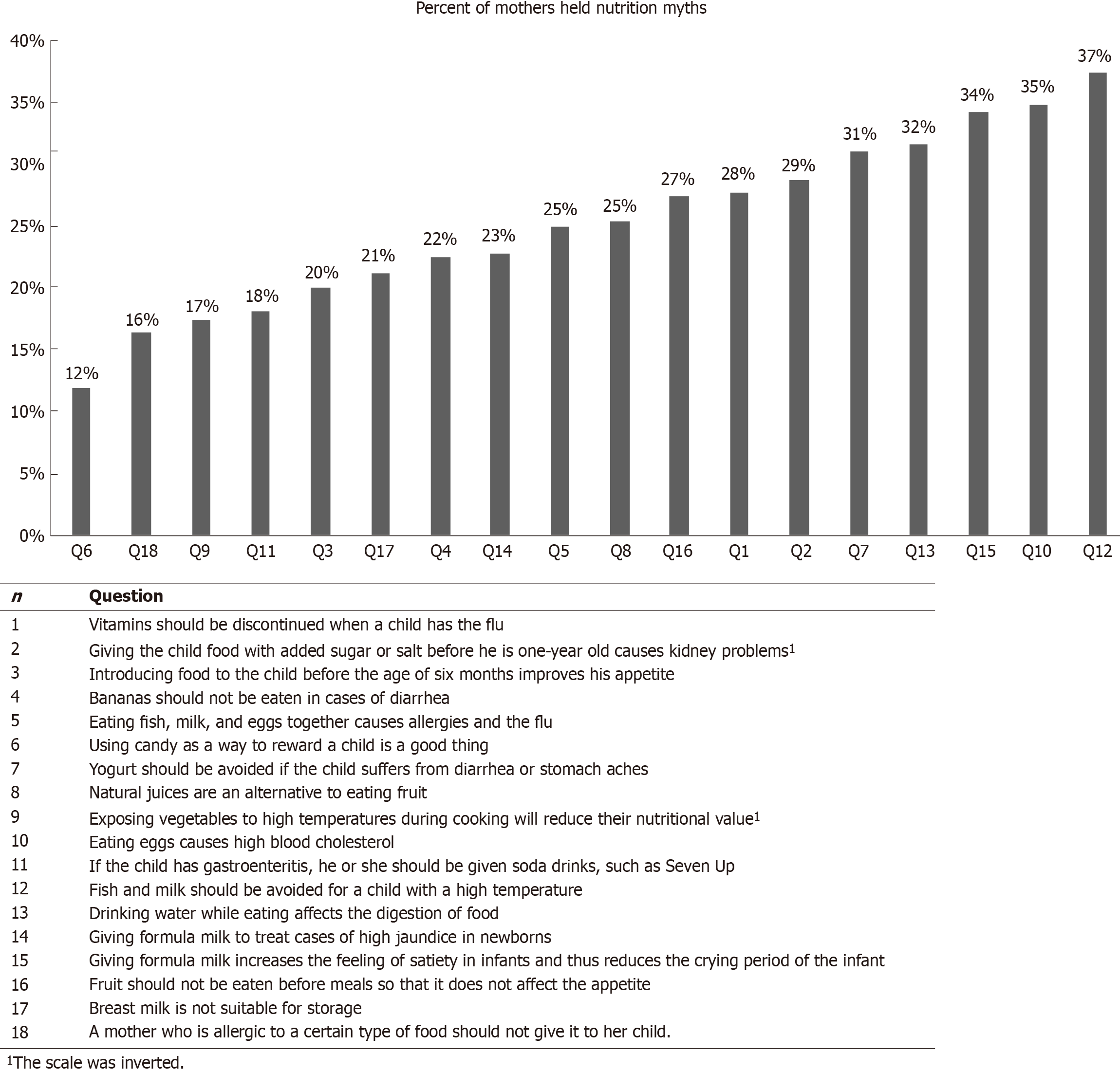

Figure 2 shows the percentage of mothers holding nutrition myths. As an example, it was found that 37% of mothers agreed that fish and milk should be avoided if the child is suffering from fever. Only 12% of mothers agreed that using candy to reward a child was a good idea.

The participants were categorized according to their responses to the GNKQ into the low knowledge group (≤ 70% GNKQ percent score) and the moderate to high knowledge group (> 70% GNKQ percent score). When comparing those groups based on their socio-demographic backgrounds, it was found that there was no statistical difference between the two groups regarding the socio-demographic backgrounds of the mothers and their families.

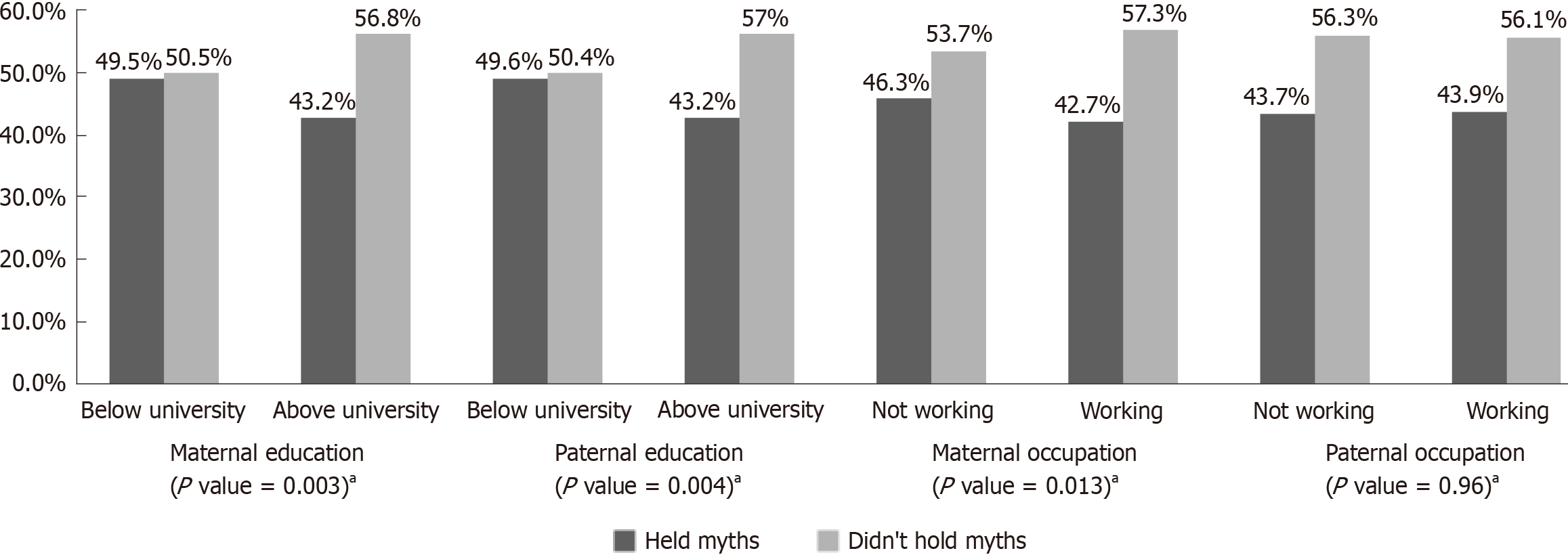

In the comparison between the mothers who held myths (with a median score of less than 9) and those who did not (with a median score of 9 or more) by their socioeconomic background, it was detected that there was no statistically significant difference except for maternal and paternal education and maternal occupation (P = 0.003, 0.004, and 0.013, respectively), as illustrated in Figure 3.

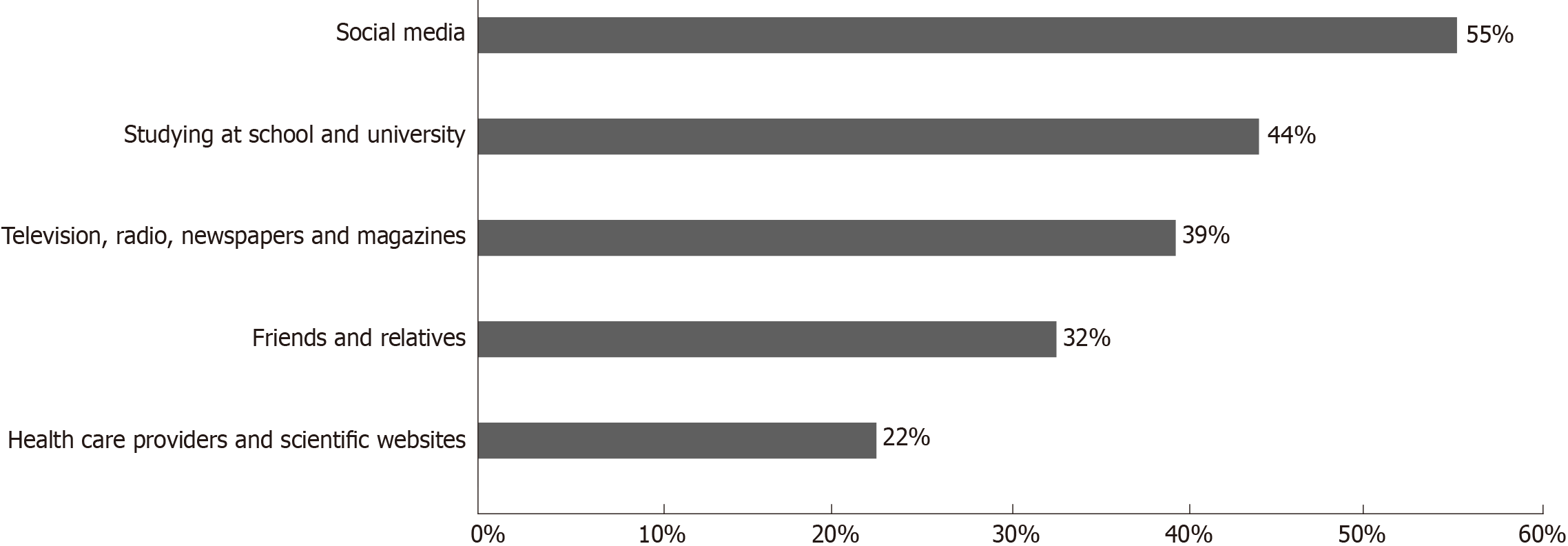

The primary source of nutrition knowledge for the enrolled mothers was social media (55%) (Figure 4).

Table 2 portrays how the mothers used to collect health information, with around half managing information for currency and authority except for viewing the author's contact information. More than 60% regularly checked information for its accuracy and purpose.

| Domain | Question | Always | Usually | Often | Sometimes | Never |

| Currency | When was the information published or posted? | 1216 (23.6) | 1360 (26.4) | 1611 (31.3) | 805 (15.6) | 156 (3.0) |

| Has the information been revised or updated? | 1181 (22.9) | 1423 (27.6) | 1549 (30.1) | 802 (15.6) | 193 (3.7) | |

| Authority | Who is the author/publisher/source/sponsor? | 1453 (28.2) | 1351 (26.2) | 1243 (24.1) | 876 (17.0) | 225 (4.4) |

| What are the author's qualifications to write on the topic? | 1399 (27.2) | 1357 (26.4) | 1219 (23.7) | 907 (17.6) | 266 (5.2) | |

| Is there contact information such as a publisher or e-mail address? | 512 (9.9) | 763 (14.8) | 1300 (25.3) | 1786 (34.7) | 787 (15.3) | |

| Accuracy | Is the information supported by evidence? | 1625 (31.6) | 1562 (30.35) | 1264 (24.6) | 530 (10.3) | 167 (3.2) |

| Purpose | What is the purpose of the information? To inform? Teach? Sell? Entertain? Persuade? | 1617 (31.4) | 1561 (30.3) | 1143 (22.2) | 621 (12.1) | 206 (4.0) |

| Does the point of view appear objective and impartial? | 1260 (24.5) | 1697 (33.0) | 1282 (24.9) | 677 (13.2) | 232 (4.5) | |

| Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional, or personal biases? | 1214 (23.6) | 1317 (25.6) | 1160 (22.5) | 987 (19.25) | 470 (9.1) |

Table 3 shows ways of managing information among participants with low, intermediate, and high nutritional knowledge and participants who held and did not hold dietary myths. It was discovered that mothers with significantly high nutrition knowledge regularly checked for the author's contact information (P = 0.012). The nutrition myth score was considerably lower among mothers who periodically checked the evidence of the information (P = 0.016).

| Nutrition knowledge | Nutrition myths | |||||

| Low nutrition knowledge | Intermediate to high nutrition knowledge | P value | Holding nutrition myths | Not holding nutrition myths | P value | |

| Currency/When was the information published or posted? | ||||||

| Always | 417 (34.3) | 799 (65.7) | 0.852 | 528 (43.4) | 688 (56.6) | 0.441 |

| Usually | 447 (32.9) | 913 (67.1) | 581 (42.7) | 779 (57.3) | ||

| Often | 559 (34.7) | 1052 (65.3) | 706 (43.8) | 905 (56.2) | ||

| Sometimes | 278 (34.5) | 527 (65.5) | 377 (46.8) | 428 (53.2) | ||

| Never | 55 (35.3) | 101 (64.7) | 70 (44.9) | 86 (55.1) | ||

| Currency/Has the information been revised or updated? | ||||||

| Always | 405 (34.3) | 776 (65.7) | 0.571 | 507 (42.9) | 674 (57.1) | 0.258 |

| Usually | 461 (32.4) | 962 (67.6) | 623 (43.8) | 800 (56.2) | ||

| Often | 542 (35.0) | 1007 (65.0) | 664 (42.9) | 885 (57.1) | ||

| Sometimes | 283 (35.3) | 519 (64.7) | 380 (47.4) | 422 (52.6) | ||

| Never | 65 (33.7) | 128 (66.3) | 88 (45.6) | 105 (54.4) | ||

| Authority/Who is the author/publisher/source/sponsor? | ||||||

| Always | 495 (34.1) | 958 (65.9) | 0.988 | 636 (43.8) | 817 (56.2) | 0.947 |

| Usually | 459 (34.0) | 892 (66.0) | 605 (44.8) | 746 (55.2) | ||

| Often | 427 (34.4) | 816 (65.6) | 541 (43.5) | 702 (56.5) | ||

| Sometimes | 295 (33.7) | 581 (66.3) | 379 (43.3) | 497 (56.7) | ||

| Never | 80 (35.6) | 145 (64.4) | 101 (44.9) | 124 (55.1) | ||

| Authority/What are the author's qualifications to write on the topic? | ||||||

| Always | 489 (35.0) | 910 (65.0) | 0.225 | 610 (43.6) | 789 (56.4) | 0.511 |

| Usually | 431 (31.8) | 926 (68.2) | 604 (44.5) | 753 (55.5) | ||

| Often | 432 (35.4) | 787 (64.6) | 513 (42.1) | 706 (57.9) | ||

| Sometimes | 306 (33.7) | 601 (66.3) | 413 (45.5) | 494 (54.5) | ||

| Never | 98 (36.8) | 168 (63.2) | 122 (45.9) | 144 (54.1) | ||

| Authority/Is there contact information such as a publisher or e-mail address? | ||||||

| Always | 192 (37.5) | 320 (62.5) | 0.012a | 229 (44.7) | 283 (55.3) | 0.786 |

| Usually | 250 (32.8) | 513 (67.2) | 323 (42.3) | 440 (57.7) | ||

| Often | 474 (36.5) | 826 (63.5) | 575 (44.2) | 725 (55.8) | ||

| Sometimes | 561 (31.4) | 1225 (68.6) | 778 (43.6) | 1008 (56.4) | ||

| Never | 279 (35.5) | 508 (64.5) | 357 (45.4) | 430 (54.6) | ||

| Accuracy/Is the information supported by evidence? | ||||||

| Always | 553 (34.0) | 1072 (66.0) | 0.089 | 709 (43.6) | 916 (56.4) | 0.016 |

| Usually | 496 (31.8) | 1066 (68.2) | 664 (42.5) | 898 (57.5) | ||

| Often | 457 (36.2) | 807 (63.8) | 542 (42.9) | 722 (57.1) | ||

| Sometimes | 185 (34.9) | 345 (65.1) | 268 (50.6) | 262 (49.4) | ||

| Never | 65 (38.9) | 102 (61.1) | 79 (47.3) | 88 (52.7) | ||

| Purpose/What is the purpose of the information? To inform? Teach? Sell? Entertain? Persuade? | ||||||

| Always | 562 (34.8) | 1055 (65.2) | 0.716 | 714 (44.2) | 903 (55.8) | 0.67 |

| Usually | 512 (32.8) | 1049 (67.2) | 669 (42.9) | 892 (57.1) | ||

| Often | 400 (35.0) | 743 (65.0) | 498 (43.6) | 645 (56.4) | ||

| Sometimes | 209 (33.7) | 412 (66.3) | 286 (46.1) | 335 (53.9) | ||

| Never | 73 (35.4) | 133 (64.6) | 95 (46.1) | 111 (53.9) | ||

| Purpose/Does the point of view appear objective and impartial? | ||||||

| Always | 440 (34.9) | 820 (65.1) | 0.241 | 557 (44.2) | 703 (55.8) | 0.378 |

| Usually | 556 (32.8) | 1141 (67.2) | 755 (44.5) | 942 (55.5) | ||

| Often | 448 (34.9) | 834 (65.1) | 534 (41.7) | 748 (58.3) | ||

| Sometimes | 221 (32.6) | 456 (67.4) | 309 (45.6) | 368 (54.4) | ||

| Never | 91 (39.2) | 141 (60.8) | 107 (46.1) | 125 (53.9) | ||

| Purpose/Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional, or personal biases? | ||||||

| Always | 433 (35.7) | 781 (64.3) | 0.559 | 533 (43.9) | 681 (56.1) | 0.343 |

| Usually | 428 (32.5) | 889 (67.5) | 565 (42.9) | 752 (57.1) | ||

| Often | 400 (34.5) | 760 (65.5) | 492 (42.4) | 668 (57.6) | ||

| Sometimes | 333 (33.7) | 654 (66.3) | 455 (46.1) | 532 (53.9) | ||

| Never | 162 (34.5) | 308 (65.5) | 217 (46.2) | 253 (53.8) | ||

The bivariate analysis demonstrated that the likelihood of holding myths was significantly higher among those who did not depend on their study at school and university and among mothers who relied on knowledge from friends, relatives, television, radio, newspapers, and magazines (P = 0.037, < 0.001, and = 0.027, respectively). The multivariate analysis identified individuals depending on television, radio, newspapers, and magazines, consulting with friends and relatives, and using social media as independent predictors of holding myths (odds ratio [OR] = 1.15, 1.3, and 1.22, respectively). In addition to that, the bivariate analysis illustrated that the likelihood of being more knowledgeable in nutrition was significantly higher among those who did not depend on television, radio, newspapers and magazines, friends, relatives, and social media (P < 0.001) and among mothers who relied on knowledge from health care providers and scientific websites (P = 0.05). Furthermore, the multivariate analysis identified that individuals not depending on learning from television, radio, newspapers, and magazines, consulting friends and relatives, and using social media were independent factors for being more knowledgeable in nutrition (OR = 1.1, 1.2, and 1.4, respectively) (Tables 4 and 5).

| Predictor of holding nutritional myths | Holding nutrition myths | Not holding nutrition myths | Crude OR [95%CI]1 | Adjusted OR [95%CI]2 | |

| Studying at school and university | No | 1305 (45.2) | 1581 (54.8) | 0.95 [0.92-0.99] | 0.95 [0.92-0.99] |

| Yes | 957 (42.3) | 1305 (57.7) | |||

| P value | 0.037a | 0.126 | |||

| Television, radio, newspapers and magazines | No | 1336 (42.7) | 1792 (57.3) | 0.93 [0.88-0.99] | 0.93 [0.88-0.99] |

| Yes | 926 (45.8) | 1094 (54.2) | |||

| P value | 0.027a | 0.020a | |||

| Health care providers and scientific websites | No | 1741 (43.6) | 2255 (56.4) | 1.03 [0.97-1.09] | 1.03 [0.97-1.09] |

| Yes | 521 (45.2) | 631 (54.8) | |||

| P value | 0.318 | 0.044a | |||

| Friends and relatives | No | 1473 (42.4) | 2002 (57.6) | 0.89 [0.84-0.95] | 0.89 [0.84-0.95] |

| Yes | 789 (47.2) | 884 (52.8) | |||

| P value | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | |||

| Social media | No | 1051 (45.4) | 1263 (54.6) | 1.06 [0.99-1.13] | 1.06 [0.99-1.13] |

| Yes | 1211 (42.7) | 1623 (57.3) | |||

| P value | 0.053 | 0.001a | |||

| Predictor of good nutritional knowledge | Bad nutrition knowledge | Good nutrition knowledge | Crude OR [95%CI] | Adjusted OR [95%CI] | |

| Studying at school and university | No | 975 (33.8) | 1911 (66.2) | 1.02 [0.94, 1.04] | 1.09 [0.98, 1.23] |

| Yes | 781 (34.5) | 1481 (65.5) | |||

| P value | 0.577 | 0.126 | |||

| Television, radio, newspapers and magazines | No | 1132 (36.2) | 1996 (63.8) | 1.09 [1.05, 1.15] | 1.15 [1.02, 1.29] |

| Yes | 624 (30.9) | 1396 (69.1) | |||

| P value | < 0.001b | 0.02a | |||

| Health care providers and scientific websites | No | 1403 (35.1) | 2593 (64.4) | 0.85 [0.76, 0.95] | 0.87 [0.75, 0.99] |

| Yes | 353 (30.6) | 799 (69.4) | |||

| P value | 0.005a | 0.044a | |||

| Friends and relatives | No | 1108 (31.9) | 2367 (68.3) | 0.9 [0.867, 0.943] | 1.3 [1.14, 1.49] |

| Yes | 648 (38.7) | 1025 (61.3) | |||

| P value | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | |||

| Social media | No | 683 (29.5) | 1631 (70.5) | 0.81 [0.756, 0.866] | 1.22 [1.09, 1.38] |

| Yes | 1073 (37.9) | 1761 (62.1) | |||

| P value | < 0.001b | 0.001a | |||

The current study focused on evaluating healthy maternal nutritional knowledge and exploring nutrition-related myths among the surveyed mothers in the setting of an LMIC (Egypt), where the per capita income ranged between 1136 and 4465 dollars, according to the World Bank, 2023[17]. In addition, it determined the sources of this nutritional information and the assessment of their sources.

The response rate was 99.4% among the surveyed mothers, with 5148 maternal responses to the online survey. The present work reported that the median maternal nutritional knowledge score on the 13 identified questions was 27 out of 41 (73.2%). Accordingly, about half (57.6%) of the respondents had good nutritional knowledge.

The present study demonstrated that mothers referred to multiple sources of nutrition information. The primary source of nutrition information among the interviewed mothers was social media platforms (55%). At the same time, healthcare providers were the source for 22% of the surveyed mothers. Consistent with the results of this study, Griauzde et al[18] in 2020 found that 46.3% of recruited Hispanic mothers in Michigan (United States) used social media to explore feeding information for their children. However, other studies in Australia reported that mothers gained their knowledge mainly from their mothers and, to a lesser extent, from healthcare professionals[19,20].

Moreover, the parents' online health-seeking behavior about their children's general health was similarly reported in a systematic review by Kubb et al[21] in 2020. The current study reflects the significant impact of social platforms on disseminating nutrition-related information among mothers in the community. Additionally, it highlights the great need for the health care provider to make every visit a chance to provide education and revise already-known information among those mothers. This continuous maternal education process through their healthcare providers will minimize the need to gain experience from untrusted resources.

Surprisingly, an evolving term in public health medicine, "infodemic," has emerged. This new term came out with the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic[22]. An infodemic is defined as an epidemic of information[23]. This overflow of information is not always correct; some are accurate, and others are inaccurate (misinformation and misbeliefs). Unfortunately, in LMICs like Egypt, the unfavorable effects of such a phenomenon are aggravated by health illiteracy and limited resource settings. Therefore, defining the level of knowledge and the extent of myths is critical to outlining the best approach[24].

The complicated scientific information and sources that cannot easily reach the general public were the leading causes behind mothers' searching other channels for information, mainly social media platforms[25]. According to this study, this is the situation among the surveyed mothers and the reason behind their preference for social media as a source of nutrition information. It is very challenging for mothers to determine what is reliable and evidence-based.

In light of this unique phenomenon, we gained a more profound insight into how these mothers are dealing with the sources of information. The maternal behavior towards the sources of information was analyzed. It was found that 50% of mothers checked for information, currency, and authority except for contact details. Furthermore, more than 60% of mothers checked the accuracy of the information. Aligned with the data in this study, another study among low-income Hispanic mothers in the United States demonstrated that most social media users extracted feeding information from reliable websites to avoid doubtful information on that platform[18]. Consequently, it is vital to provide accessible and trustworthy sources of nutrition information through e-health education or smartphone health applications supplied by the Ministry of Health.

Further analysis of factors affecting maternal knowledge scores was conducted by comparing mothers with good nutrition knowledge to those with inappropriate nutrition knowledge. It was previously reported in Turkey that maternal age is one of the essential factors affecting knowledge, attitude, and behavior[26]. As expected, when getting older, the mother becomes more experienced and are able to gain and process information wisely. However, the data in this research demonstrated no significant differences between different maternal age groups regarding maternal knowledge scores (P = 0.31). A similar result from Turkey was found by Demir et al[27] in 2020, who reported that knowledge scores were almost identical among different maternal age groups except for those between 26 and 30 years, who had higher scores.

In addition, the maternal knowledge status was analyzed according to maternal education and paternal education, and it was not significantly different (P = 0.64 and 0.64, respectively). However, it was different from other reports from Ghana, the United Arab Emirates, and Turkey, where the level of knowledge score was positively correlated with maternal education level[27-30].

It is assumed that mothers acquire experience in nutrition and different health aspects when having more than one child or when children are getting older. However, this research discovered no difference regarding the nutrition knowledge scale according to the child's age, order, or sex.

A dietary myth is a negative or positive belief regarding nutritional concepts that cannot be supported or opposed by scientific evidence[31]. According to the extent of belief in myths, the healthy behavior of parents and, consequently, the nutritional status of their children are affected.

Regarding the nutrition myth score, the median score was 9 out of 18 (50%). Therefore, 56% of the mothers did not hold nutrition myths. This study found that the most frequent nutrition myth was reported by about 37% of respondents about avoiding eating fish and milk if the child was feverish.

However, the least frequently determined myth by only 12% of respondents was about rewarding children with candy. This behavior supports the recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics, which is against the administration of unnecessary additional calories as it increases the risk of obesity among children.

This study demonstrated that maternal education was significantly different between mothers with nutrition myths and those without (P = 0.003). Those with higher education (above the university) had substantially lower myth scores. Although the education level of mothers was not related to the maternal nutrition knowledge score, it was related to the lower myth group. This information emphasizes the importance of maternal education, even if only it positively reduces the myth belief. This differs from the results of Mrosková et al[32], who found that maternal education was related to food choices, whether healthy or not, but not associated with paternal myth belief.

Further analysis of other factors related to nutrition myths revealed that maternal occupation was significantly different between the two groups. Substantially, more working mothers were not holding nutrition myths (P = 0.013). It could be assumed that employment raises socialization and awareness among mothers.

Additionally, logistic regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of the five different sources of nutrition information on the development of nutrition myths. Interestingly, it was found that using social media, consulting with family members, and depending on knowledge from television, radio, newspapers, and magazines increased the likelihood of holding myths among mothers approximately 1.2, 1.3, and 1.14 times more than mothers who do not depend on those sources as a source of knowledge. However, mothers dependent on their health care providers and scientific websites are less likely to hold myths by 13%. This information emphasizes that informal sources of nutritional information increase the incidence of nutrition myths. However, using formal sources through health care providers and scientific websites positively decreased the misinformation rate. Regulatory health authorities should provide sufficient nutrition training for general pediatricians for that finding. In addition to that, adequate auditing for non-supervised nutrition training courses is deeply needed to minimize the incidence of myths among physicians and mothers.

Since the survey was online, this gave the researcher more freedom to answer than a physical interview. Furthermore, it was less expensive and took less time. The study was a nationwide survey with randomly selected mothers from many governorates nationwide. The online survey involved only mothers who could access the Internet, which limited the conclusion. Future research, including all mothers, is needed to help identify the different sources and barriers of nutritional myths and knowledge among different socioeconomic levels.

In our LMIC setting, almost 50% of the mothers had good nutrition knowledge level scores. In the era of infodemics, social media platforms were the principal source of nutrition information, with more than 50% of mothers managing information currency and authority. For this finding, novel strategies are needed to raise maternal awareness for proper evaluation and selection of the suitable material offered through these platforms. In addition, updated maternal nutrition information sources should be developed and managed by different health authorities. Mothers holding nutritional myths represented 56% of the surveyed mothers. Maternal education and occupation reduced the frequency of myths and beliefs. Health care providers, as sources of nutritional information, are the only source of information, decreasing the mythic incidence among mothers.

Nowadays, diversity of sources of maternal nutritional education becomes a fact in the light of infodemics era. Evaluation of these sources and the method of their assessment is crucial to improve the practice. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published study from Egypt evaluating this problem in spite of its significance in this low/middle income country.

Healthcare providers, family members, mass media, and social media are different sources of maternal information. Technology enables faster delivery of information but cannot guarantee acquiring the right information. The results of the current study will help to innovate novel strategies to improve maternal awareness for proper evaluation and selection of the suitable material offered to them through different sources.

To assess the healthy nutritional knowledge and nutrition related myths among a large sample of Egyptian mothers, and to determine the sources of these information and how those mothers mange the sources of nutritional related knowledge.

This cross-sectional analytical observational study enrolled 5148 randomly selected Egyptian mothers who had one or more children less than 15 years old. The data were collected through online questionnaire forms: One was for the general nutrition knowledge assessment, and the other was for the nutritional myth score. Sources of information and ways of evaluating internet sources using the Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose test were additionally analyzed.

The main source of maternal nutrition knowledge was social media platforms (55%). Half of the mothers managed information for currency and authority, except for considering the author's contact information. The mothers with higher nutrition knowledge checked periodically for the author's contact information (P = 0.012). The nutrition myth score was significantly lower among mothers who periodically checked the evidence of the information (P = 0.016). Mothers dependent on their healthcare providers as the primary source of their general nutritional knowledge were less likely to hold myths by 13% (P = 0.044). However, using social media increased the likelihood of having myths among mothers by 1.2 (P = 0.001).

In the era of infodemics, social media platforms are the principal source of nutrition information, with more than 50% of mothers managing information currency and authority. Health care providers, as sources of nutritional information, are the only source of information, decreasing the myth incidence among mothers.

The online survey involved only mothers who could access the internet, which limited the conclusion. Future research, including all mothers, is needed to help identify the different sources and barriers of nutritional myths and knowledge among different socioeconomic levels.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Nutrition and dietetics

Country/Territory of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Peng XC, China; Zhao H, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhao YQ

| 1. | Karlsson O, Kim R, Hasman A, Subramanian SV. Age Distribution of All-Cause Mortality Among Children Younger Than 5 Years in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2212692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Das JK, Salam RA, Saeed M, Kazmi FA, Bhutta ZA. Effectiveness of Interventions for Managing Acute Malnutrition in Children under Five Years of Age in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lassi ZS, Rind F, Irfan O, Hadi R, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. Impact of Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) Nutrition Interventions on Breastfeeding Practices, Growth and Mortality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Soofi SB, Khan GN, Ariff S, Ihtesham Y, Tanimoune M, Rizvi A, Sajid M, Garzon C, de Pee S, Bhutta ZA. Effectiveness of nutritional supplementation during the first 1000-days of life to reduce child undernutrition: A cluster randomized controlled trial in Pakistan. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2022;4:100035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ponum M, Khan S, Hasan O, Mahmood MT, Abbas A, Iftikhar M, Arshad R. Stunting diagnostic and awareness: impact assessment study of sociodemographic factors of stunting among school-going children of Pakistan. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lesser LI, Mazza MC, Lucan SC. Nutrition myths and healthy dietary advice in clinical practice. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:634-638. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Apetrei C, Marx PA, Mellors JW, Pandrea I. The COVID misinfodemic: not new, never more lethal. Trends Microbiol. 2022;30:948-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | 8 Huckvale K, Nicholas J, Torous J, Larsen ME. Smartphone apps for the treatment of mental health conditions: status and considerations. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;36:65-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet. 2020;395:676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1148] [Cited by in RCA: 998] [Article Influence: 199.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kasiulevičius V, Sapoka V, Filipavičiūtė R. Sample size calculation in epidemiological studies. Gerontologija. 2006;7:225-231. |

| 11. | Sultana P, Hasan KM. Mother's Nutritional Knowledge and Practice: A study on Slum Area of Khulna City. EJMED. 2020;2:582. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Central Agency of Public Mobilization and Statistics (2020). Annual Bulletin of Births and Deaths 2020. CAPMS. Available at https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/Publications.aspx?page_id=5104&YearID=23543. |

| 13. | Bataineh MF, Attlee A. Reliability and validity of Arabic version of revised general nutrition knowledge questionnaire on university students. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:851-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Scalvedi ML, Gennaro L, Saba A, Rossi L. Relationship Between Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake: An Assessment Among a Sample of Italian Adults. Front Nutr. 2021;8:714493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sámano R, Lara-Cervantes C, Martínez-Rojano H, Chico-Barba G, Sánchez-Jiménez B, Lokier O, Hernández-Trejo M, Grosso JM, Heller S. Dietary Knowledge and Myths Vary by Age and Years of Schooling in Pregnant Mexico City Residents. Nutrients. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Muis KR, Denton C, Dubé A. Identifying CRAAP on the Internet: A Source Evaluation Intervention. ASSRJ. 2022;9:239-265. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Ponce P, López-Sánchez M, Guerrero-Riofrío P, Flores-Chamba J. Determinants of renewable and non-renewable energy consumption in hydroelectric countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27:29554-29566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Griauzde DH, Kieffer EC, Domoff SE, Hess K, Feinstein S, Frank A, Pike D, Pesch MH. The influence of social media on child feeding practices and beliefs among Hispanic mothers: A mixed methods study. Eat Behav. 2020;36:101361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ball R, Duncanson K, Burrows T, Collins C. Experiences of Parent Peer Nutrition Educators Sharing Child Feeding and Nutrition Information. Children (Basel). 2017;4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Duncanson K, Burrows T, Collins C. Peer education is a feasible method of disseminating information related to child nutrition and feeding between new mothers. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kubb C, Foran HM. Online Health Information Seeking by Parents for Their Children: Systematic Review and Agenda for Further Research. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Briand SC, Cinelli M, Nguyen T, Lewis R, Prybylski D, Valensise CM, Colizza V, Tozzi AE, Perra N, Baronchelli A, Tizzoni M, Zollo F, Scala A, Purnat T, Czerniak C, Kucharski AJ, Tshangela A, Zhou L, Quattrociocchi W. Infodemics: A new challenge for public health. Cell. 2021;184:6010-6014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rothkopf DJ. When the Buzz Bites Back. The New York Times. 2003;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Dash S, Parray AA, De Freitas L, Mithu MIH, Rahman MM, Ramasamy A, Pandya AK. Combating the COVID-19 infodemic: a three-level approach for low and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ruths D. The misinformation machine. Science. 2019;363:348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ozdogan Y, Uçar A, Akan LS, Yılmaz MV, Sürücüoğlu MS, Cakıroğlu FP, Ozcelik AO. Nutritional knowledge of mothers with children aged between 0-24 months. J Food Agric Environ. 2020;10:173-175. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Demir G, Yardımcı H, Çakıroğlu FP, Özçelik AÖ. Knowledge of Mothers with Children Aged 0-24 Months on Child Nutrition. Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi. 2020;270-278. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Webb P, Lapping K. Are the determinants of malnutrition the same as for food insecurity? Recent findings from 6 developing countries on the interaction between food and nutrition security. Food Policy and Applied Nutrition Program. 2002l; Discussion Paper 6. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Appoh LY, Krekling S. Maternal nutritional knowledge and child nutritional status in the Volta region of Ghana. Matern Child Nutr. 2005;1:100-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Al Ketbi MI, Al Noman S, Al Ali A, Darwish E, Al Fahim M, Rajah J. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of breastfeeding among women visiting primary healthcare clinics on the island of Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Baldick Ch. Oxford dictionary of literary terms. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2015. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Mrosková S, Lizáková Ľ. Nutrition myths - the factor influencing the quality of children's diets. Cent Eur J Nurs Midw. 2016;7:384-389. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |