Published online Sep 9, 2023. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v12.i4.205

Peer-review started: April 28, 2023

First decision: May 25, 2023

Revised: June 9, 2023

Accepted: July 7, 2023

Article in press: July 7, 2023

Published online: September 9, 2023

Processing time: 130 Days and 11.3 Hours

Children like to discover their environment by putting substances in their mouths. This behavior puts them at risk of accidentally ingesting foreign bodies (FBs) or harmful materials, which can cause serious morbidities.

To study the clinical characteristics, diagnosis, complications, management, and outcomes of accidental ingestion of FBs, caustics, and medications in children.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all children admitted for accidental ingestion to the Department of Pediatrics, Salmaniya Medical Complex, Bahrain, between 2011 and 2021. Demographic data, type of FB/harmful material ingested, and investigations used for diagnosis and management were recorded. The patients were divided into three groups based on the type of ingested material (FBs, caustics, and medications). The three groups were compared based on patient demographics, socioeconomic status (SES), symptoms, ingestion scenario, endoscopic and surgical complications, management, and outcomes. The FB anatomical location was categorized as the esophagus, stomach, and bowel and compared with respect to symptoms. The Fisher’s exact, Pearson’s χ2, Mann-Whitney U, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for comparison.

A total of 161 accidental ingestion episodes were documented in 153 children. Most children were boys (n = 85, 55.6%), with a median age of 2.8 (interquartile range: 1.8-4.4) years. Most participants ingested FBs (n = 108, 70.6%), 31 (20.3%) ingested caustics, and the remaining 14 (9.2%) ingested medications. Patients with caustic ingestion were younger at the time of presentation (P < 0.001) and were more symptomatic (n = 26/31, 89.7%) than those who ingested medications (n = 8/14, 57.1%) or FBs (n = 52/108, 48.6%) (P < 0.001). The caustic group had more vomiting (P < 0.001) and coughing (P = 0.029) than the other groups. Most FB ingestions were asymptomatic (n = 55/108, 51.4%). In terms of FB location, most esophageal FBs were symptomatic (n = 14/16, 87.5%), whereas most gastric (n = 34/56, 60.7%) and intestinal FBs (n = 19/32, 59.4%) were asymptomatic (P = 0.002). Battery ingestion was the most common (n = 49, 32%). Unsafe toys were the main source of batteries (n = 22/43, 51.2%). Most episodes occurred while playing (n = 49/131, 37.4%) or when they were unwitnessed (n = 78, 57.4%). FBs were ingested more while playing (P < 0.001), caustic ingestion was mainly due to unsafe storage (P < 0.001), and medication ingestion was mostly due to a missing object (P < 0.001). Girls ingested more jewelry items than boys (P = 0.006). The stomach was the common location of FB lodgment, both radiologically (n = 54/123, 43.9%) and endoscopically (n = 31/91, 34%). Of 107/108 (99.1%) patients with FB ingestion, spontaneous passage was noted in 54 (35.5%), endoscopic removal in 46 (30.3%), laparotomy in 5 (3.3%) after magnet ingestion, and direct laryngoscopy in 2 (1.3%). Pharmacological therapy was required for 105 (70.9%) patients; 79/105 (75.2%) in the FB group, 22/29 (75.9%) in the caustic group, and 4/14 (28.8%) in the medication group (P = 0.001). Omeprazole was the commonly used (n = 58; 37.9%) and was used more in the caustic group (n = 19/28, 67.9%) than in the other groups (P = 0.001). Endoscopic and surgical complications were detected in 39/148 (26.4%) patients. The caustic group had more complications than the other groups (P = 0.036). Gastrointestinal perforation developed in the FB group only (n = 5, 3.4%) and was more with magnet ingestion (n = 4) than with other FBs (P < 0.001). In patients with FB ingestion, patients aged < 1 year (P = 0.042), those with middle or low SES (P = 0.028), and those with more symptoms at presentation (P = 0.027) had more complications. Patients with complications had longer hospital stays (P < 0.001) than those without.

Accidental ingestion in children is a serious condition. Symptomatic infants from middle or low SES families have the highest morbidity. Prevention through parental education and government legislation is crucial.

Core Tip: Foreign body (FB) or harmful material ingestion is common in pediatric patients. These accidents occur more frequently among boys. Toddlers are at a higher risk of accidental ingestion because of their exploratory behavior. Batteries are the most commonly ingested FBs. Many ingestion incidents have occurred while playing and because of unsafe storage. The stomach is the most common anatomical location of FB loosening on radiography and endoscopy. Caregiver education regarding preventive methods and governmental execution of safe manufacturing of toys, magnets, and batteries is essential to prevent FB ingestion and the complications that might occur.

- Citation: Isa HM, Aldoseri SA, Abduljabbar AS, Alsulaiti KA. Accidental ingestion of foreign bodies/harmful materials in children from Bahrain: A retrospective cohort study. World J Clin Pediatr 2023; 12(4): 205-219

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v12/i4/205.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v12.i4.205

Children like to discover their environment by putting substances into their mouth[1]. Accidental ingestion of foreign bodies (FBs) or caustic materials is a common problem encountered by families with children. It is considered as one of the most common indications for emergency referral and hospital admission. There are diverse types of FBs or ingested materials that can be swallowed by children. Coins, toy parts, jewelry, button-type batteries, needles, and pins are the most frequently ingested materials[1].

Most ingested FBs pass spontaneously, and patients can be safely observed[2]. Although most ingestion incidents are insignificant in terms of consequences, a few can pose a challenging problem that may lead to serious life-threatening complications[2]. For example, numerous magnetic objects located at various sites in the bowel can attract one another, leading to pressure necrosis of the bowel wall and eventual perforation[1]. Furthermore, although batteries can pass easily through the digestive tract and are eliminated from the stool within a few days of ingestion, swallowing batteries is more dangerous than swallowing coins or other inert objects because of their electrochemical composition and high risk of local damage[3]. Moreover, batteries 20 mm or larger in size can affect the esophagus, especially in young children[3]. Strong exothermic reactions can lead to serious mucosal injuries that may appear as skin burns[3]. Caustic ingestion is also common in pediatric age groups, and most cases happen accidentally[4]. The seriousness of this ingestion is due to the tissue injury and necrosis[4]. Tissue damage can start from the mucosa and extend to the muscular layers, causing multiple complications, such as burns, strictures, and perforations[4].

Prompt diagnosis of accidental ingestion, appropriate management, and a decision on whether the patient necessitates intervention are crucial for reducing morbidity[2]. The type of FB, anatomic location in which the FB is lodged, and clinical picture of the patient determine the timing of endoscopic removal of the swallowed FB[2,3]. In children with caustic ingestion, postoperative treatment remains controversial and includes entities such as antireflux therapy, antibiotic therapy, steroids, and interventions such as esophageal stenting[3]. Nonetheless, the implementation of preventive methods and safe storage of caustic materials is essential to avoid these accidents and their related conse

Although many studies on accidental ingestion in children have been published in several countries, no studies have been published on this issue in Bahrain. The aim of this study was to review the incidence, demographics, different types of FBs/harmful materials, diagnostic modalities, complications, and outcomes of accidental ingestion in a pediatric age group and compare patients with endoscopic or surgical complications with those without complications to identify the predicted risk factors.

In this retrospective cohort study, all pediatric patients (aged < 18 years) who presented to the Department of Accident and Emergency with a history of accidental ingestion and were admitted to the Department of Pediatrics, Salmaniya Medical Complex, Bahrain from January, 2011 to August, 2021 were included. Patients who presented to the Department of Accident and Emergency and were subsequently discharged were excluded.

Patient data were collected by reviewing electronic and paper-based medical records. Important missing data were retrieved through direct contact with the patients’ parents or guardians via telephone. Demographic data, including year of admission, nationality, sex, age at presentation, and age at the time of the study, were collected. Data on families’ socioeconomic status (SES) were collected, including paternal and maternal educational levels, occupation, number of children, and total family income. Accordingly, families were categorized into low-, middle-, and high-SES groups. Data on symptoms at presentation, including vomiting, abdominal pain, passing tarry stool, choking, dysphagia, drooling of saliva, shortness of breath, and coughing, were collected. Details related to accidental ingestion of FBs, including the type, number, and source of FBs, were collected. Additionally, the presence of witnesses at the time of accidental ingestion, time to presentation to the Department of Accident and Emergency, and spontaneous passage times were outlined. More details regarding the type of battery were collected from the patients who ingested batteries.

Radiological imaging findings, endoscopic findings, and extraction methods were also reviewed. Urgent endoscopy was considered if it was performed within 48 h of ingestion, whereas a longer time was considered a delayed endoscopy. Data on the patients’ hospital management, including endoscopic removal and the use of medications, such as lactulose, enema, glycerin suppositories, and omeprazole, were gathered. Furthermore, data on patient outcomes, including length of stay, morbidity, mortality, and follow-up period, were assessed.

Patient data were initially collected and entered into an Excel sheet and then transferred to and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Categorical vari

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was ethically approved by the Secondary Health Care Research Committee, Salmaniya Medical Complex, Government Hospitals, Kingdom of Bahrain (IRB number: 88300719, July 30, 2019).

During the study period, 161 accidental ingestion episodes were documented in 153 children admitted to the hospital, all of whom were included in this study. Eight (5.0%) patients had another episode of accidental ingestion following the initial episode; one of them had three episodes in total, and two patients ingested the same object (battery or hard food) during the two episodes. Of the eight patients with multiple ingestions, three (37.5%) had neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism, demyelination, and mild intellectual disability. The latter had iron-deficiency anemia associated with pica. The patient with three episodes had disc battery ingestion, followed by two repeated FB ingestions, and was referred to the child protection team because of suspected child neglect, as this patient also had repeated burn events.

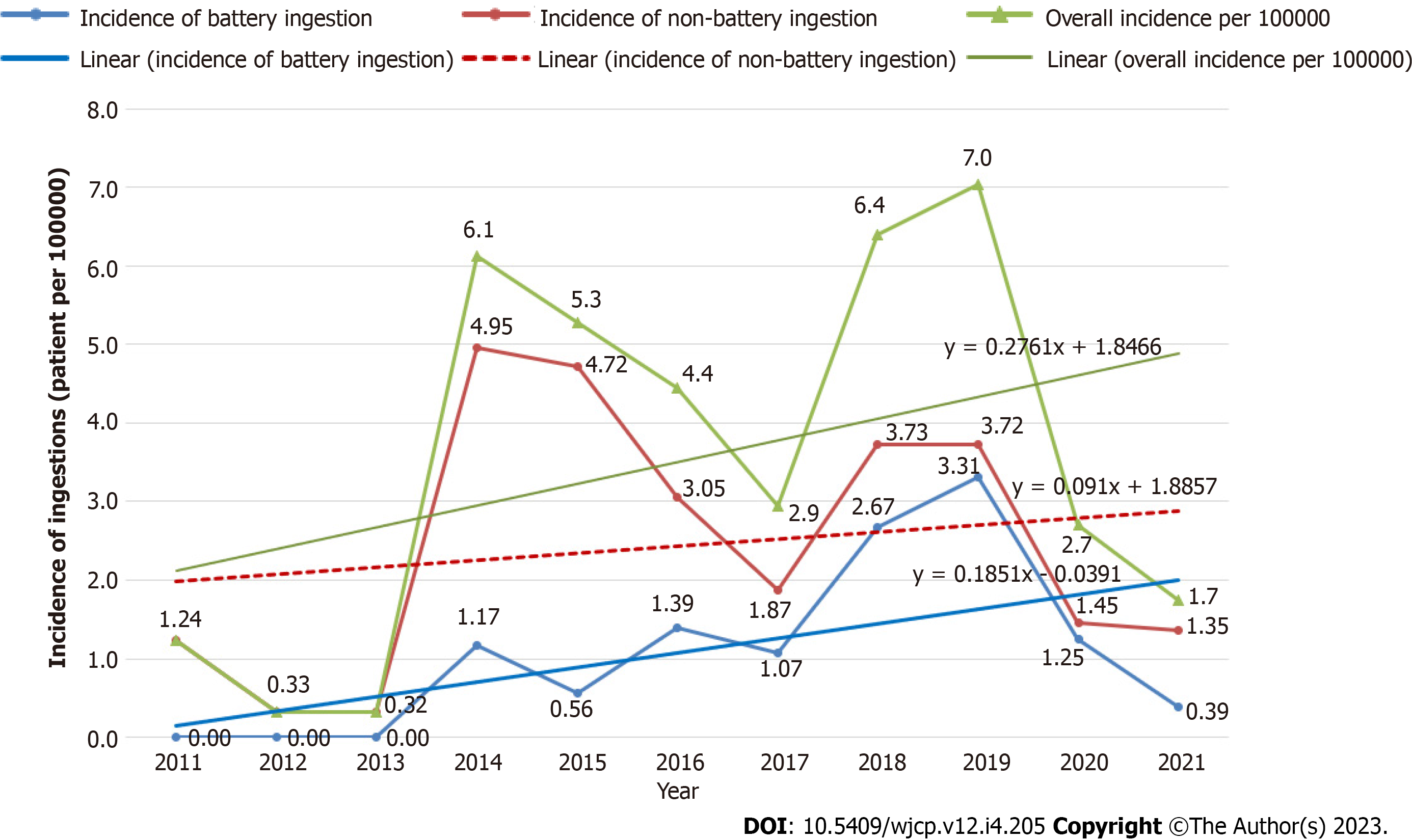

The mean number of accidental ingestions was 13.9 ± 10.3 episodes per year. The annual incidence of accidental ingestion episodes is shown in Figure 1. The incidence of accidental ingestion increased during the study period. In 2012-2016, the mean incidence was 3.3 ± 2.8 compared to 4.2 ± 2.4 episodes in 2017-2021. However, this increase was not statistically significant (P = 0.610, 95%CI: -4.6 to 2.9).

The demographic data and clinical presentations are shown in Table 1. Most of the patients ingested FBs (n = 108, 70.6%), 31 (20.3%) ingested caustic chemicals, and the remaining 14 (9.2%) ingested medications. Most of the patients were boys (n = 85, 55.6%). Most patients were Bahraini children (n = 118, 77.1%), while non-Bahraini children accounted for 35 (22.9%) patients (10 from India, 5 from Saudi Arabia, 2 from Bangladesh and United States of America each, 1 from Egypt, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Yemen, and Syria each, while 8 patients had unspecified nationalities). The median age at presentation was 2.8 (IQR: 1.8-4.4) years, and the most frequent age group was 2-3 years old, accounting for 43.5%. Patients with caustic ingestion were younger than those who ingested medications or FBs at the time of presentation (P < 0.001). Most patients (n = 119, 77.8%) ingested one item, and most were symptomatic (n = 86, 57.3%). The most common symptom was vomiting (n = 44, 29.3%), followed by abdominal pain (n = 25, 16.7%). Patients with caustic ingestion (n = 26/31, 89.7%) were more symptomatic than those who ingested medications (n = 8/14, 57.1%) or FBs (n = 52/108, 48.6%) (P < 0.001). The caustic group had more vomiting (P < 0.001) and coughing (P = 0.029) than the other two groups. Most of patients with FB ingestion were asymptomatic (n = 55/108, 51.4%). Upon comparison of symptoms according to the location of FBs (esophagus, stomach, or bowel), most of the 16 patients with esophageal FBs were found to be symptomatic [14 (87.5%) vs 2 (12.5%)], while the majority of the 56 patients with gastric FBs [34 (60.7%) vs 22 (39.3%)] and the 32 patients with intestinal FBs [19 (59.4%) vs 13 (40.6%)] were asymptomatic (P = 0.002).

| Demographic data | Total, n = 153 (100) | FB, n = 108 (70.6) | Caustic, n = 31 (20.3) | Medication, n = 14 (9.2) | P value |

| Sex | 0.513a | ||||

| Male | 85 (55.6) | 58 (53.7) | 20 (64.5) | 7 (50) | |

| Female | 68 (44.4) | 50 (46.3) | 11 (35.5) | 7 (50) | |

| Nationality | 0.260a | ||||

| Bahraini | 118 (77.1) | 87 (80.6) | 22 (71.0) | 9 (64.3) | |

| Non-Bahraini | 35 (22.9) | 21 (19.4) | 9 (29.0) | 5 (35.7) | |

| Socioeconomic status (n = 95) | 0.520a | ||||

| Low | 32 (33.7) | 26 (34.7) | 3 (20.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Middle | 31 (32.6) | 25 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | 1 (20.0) | |

| High | 32 (33.7) | 24 (32.0) | 7 (46.7) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Working mother | 33/95 (34.7) | 28/75 (37.3) | 4/15 (26.7) | 1/5 (20.0) | 0.568a |

| Number of siblings, (n = 94) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 0.877b |

| Age at presentation (yr), (n = 152) | 2.8 (1.8-4.4) | 3.4 (2.0-5.6) | 1.8 (1.5-2.5) | 2.6 (2.1-2.8) | < 0.001b |

| Age categories (yr), (n = 152) | 0.001a | ||||

| 0-1 | 41 (27) | 22 (20.6) | 17 (54.8) | 2 (14.3) | |

| 2-3 | 66 (43.4) | 45 (42.1) | 11 (35.5) | 10 (71.4) | |

| 4-5 | 31 (20.4) | 27 (25.2) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (14.3) | |

| ≥ 6 | 14 (9.2) | 13 (12.1) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Time to presentation (h), (n = 139) | 2.0 (1.0-6.0) | 2.0 (1.0-6.0) | 1.0 (0.3-5.0) | 2.0 (1.0-4.0) | 0.306b |

| Length of stay (d) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | 1.0 (1.0-4.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 0.063b |

| Length of stay categories (d), (n = 146) | 0.102a | ||||

| 0-1 | 104 (71.2) | 74 (71.8) | 16 (55.2) | 14 (100) | |

| 2-3 | 20 (13.7) | 15 (14.6) | 5 (17.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 4-5 | 7.0 (4.8) | 5 (4.9) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ≥ 6 | 15 (10.3) | 9 (8.7) | 6 (20.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Number of ingested FBs/materials per patient | 0.053a | ||||

| 1 | 119 (77.8) | 81 (75.0) | 30 (96.8) | 8 (57.1) | |

| 2-5 | 23 (15.0) | 19 (17.6) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (21.4) | |

| 6-10 | 3.0 (2.0) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | |

| > 10 | 8.0 (5.2) | 6 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Clinical presentations (n = 150) | |||||

| Symptomatic1 | 86 (57.3) | 52 (48.6) | 26 (89.7) | 8 (57.1) | < 0.001a |

| Vomiting | 44 (29.3) | 23 (21.9) | 18 (62.1) | 3 (21.4) | < 0.001a |

| Abdominal pain | 25 (16.7) | 21 (20.0) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (14.3) | 0.240a |

| Cough | 13 (8.7) | 7 (6.7) | 6 (20.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.029a |

| Shortness of breath | 11 (7.3) | 6 (5.7) | 5 (17.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.060a |

| Choking | 11 (7.3) | 8 (7.6) | 3 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.475a |

| Dysphagia/drooling of saliva | 9 (6.0) | 5 (4.6) | 4 (12.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.139a |

| Convulsion | 3.0 (2.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (7.1) | 0.245a |

| Others2 | 16 (10.6) | 11 (10.2) | 4 (12.9) | 1 (7.1) | 0.831a |

| Asymptomatic | 64 (42.7) | 55 (51.4) | 3 (10.3) | 6 (42.9) | < 0.001a |

| Presence of witness (n = 136) | 58 (43.6) | 38 (40.4) | 14 (50.0) | 6 (42.9) | 0.667a |

Five patients had underlying diseases that might have been related to accidental ingestion. Esophageal strictures after tracheoesophageal fistula repair were found in two patients with food bolus impaction; one patient had cerebral palsy with needle ingestion, one had mental retardation with coin ingestion, and one had autism with disc battery ingestion.

Out of 136 (88.9%) patients with available witness history, 58 (43.6%) were witnessed and 78 (57.4%) were unwitnessed. Of those witnessed, 55 (94.8%) patients had a known witness person, while 3 (5.2%) had an unknown witness. Three (5.2%) patients had more than one witness person. First degree relatives were witnesses in 47 (85.5%) patients, second degree relatives in 8 (14.6%), and unrelated people (teacher, housemaid, and family friend) in 3 (5.5%). The mother was the most frequent witness (n = 27, 49.1%), followed by other siblings [n = 11 (20%); seven of them were sisters and four were brothers] and fathers (n = 7, 12.7%).

There were no significant differences among the three groups with respect to sex, nationality, SES, maternal occupation, number of siblings, time to presentation, length of stay, number of ingested materials, or the presence of a witness.

The different types of ingested material are listed in Table 2. Battery ingestion was the most frequent FB type (n = 49, 32%); 48 of them were disc batteries, and 1 was a finger type. The sharp objects included earring, screw, and nail/nail hanger (n = 5 each), key/keyring/keychain (n = 4), needle (n = 3), hair clip/pin and sharp pin (n = 2 each), gold chain, leg accessories, necklace, pepsi cap, and zipper piece (n = 1 each). The chemicals and corrosive solutions included alkaline corrosives (n = 19; Clorox in 11 patients, detergents or disinfectants in 3 each, and nonspecific corrosives in 2 patients), acid corrosives (n = 5; keratolytic agents in three and toilet cleaners in two patients), and other chemicals (n = 6). The medications included paracetamol (n = 4), antihypertensives (n = 3, coversyl in two and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in one patient), antihistamines, hypoglycemic agents, oral contraceptives, nitrite, multivitamins, methylphenidate, and multiple medications (n = 1 each).

Even though there was no significant difference between boys and girls in terms of the type of FBs ingested (P = 0.217), in metal object ingestions, girls were found to ingest more jewelry items than boys, with seven (70%) vs three (30%), respectively (P = 0.006). Of the 49 (32%) patients who ingested batteries, 43 (87.8%) patients had the source of battery data available. Unsafe toys were the main sources of batteries (n = 22, 51.2%), followed by light torches (n = 10, 23.3%), remote-control devices (n = 2, 4.7%), artificial candles, baskets, electronic walking aids, headphones, laser pens, on car seats, on tables, and from watches and weighing scales (n = 1 each, 2.3%).

The accidental ingestion scenarios are presented in Table 3. Data regarding this scenario were available for 131 (85.6%) patients. Accidental ingestion mostly happened while the child was playing (n = 53, 40.5%). FBs were ingested more while playing (P < 0.001), caustic chemical ingestion was mainly due to unsafe storage (P < 0.001), and medication ingestion was mostly due to a missing object (P < 0.001).

| Ingestion scenario | Total, n = 1311 (100) | FB, n = 90 (68.7) | Caustic, n = 27 (20.6) | Medication, n = 14 (10.7) | P valuea |

| While playing | 53 (40.5) | 50 (55.6) | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001b |

| Unsafe storage | 46 (35.1) | 13 (14.4) | 26 (96.3) | 7 (50) | < 0.001b |

| Missing objects | 18 (13.7) | 12 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (42.9) | < 0.001b |

| Told by patient/relative | 13 (9.9) | 12 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0.118 |

| Accidental ingestion | 4 (3.1) | 4 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.391 |

| Incidental finding on X-ray | 3 (2.3) | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.497 |

| Food bolus impaction | 3 (2.3) | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.497 |

| Suicidal attempt | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.144 |

Results of radiological imaging, including chest and abdominal radiography, were available for 123 (80.4%) patients: 108 (100%) for FB, 8 (25.8%) for caustic, and 7 (50%) for medication ingestion (P < 0.001) (Table 4). The remaining 30 (24.6%) patients with no radiological findings ingested either corrosives (n = 23, 76.7%) or medications (n = 7, 23.3%). The most common location of the ingested object was the stomach both radiologically (n = 54/123, 43.9%) and endoscopically (n = 31/91, 34%).

| Foreign body location | On X-ray, n = 123/153 (80.4) | In endoscopy, n = 91/152 (59.9) |

| Esophagus | 14 (11.4) | 13 (14.3) |

| Stomach | 54 (43.9) | 31 (34.0) |

| Small intestine | 18 (14.6) | 22 (24.2) |

| Large intestine | 16 (13.0) | 1.0 (1.1) |

| Others1 | 2.0 (1.6) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Not seen/normal | 19 (15.5) | 24 (26.4) |

Endoscopic procedures were performed in 91 (59.9%) of the 152 (99.4%) patients: 73/107 (68.2%) for FB ingestion, 18/31 (58.1%) for caustic ingestion, while no patient with medication ingestion underwent endoscopy (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Ninety patients (59.2%) underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and one (0.7%) underwent colonoscopy. The common endoscopic location of the ingested objects was also the stomach (n = 31, 34%). The time from presentation to endoscopy was available for 81 (89%) patients; 78 (96.3%) of them had an emergency endoscopy (< 48 h), while 3 (3.7%) were delayed after 48 h. The first delayed patient was a 4-year-old girl who was brought by her parents with a history of fainting and vomiting streaks of blood after accidental ingestion of Clorox stored in a small water bottle. The second patient was an 8-year-old boy who ingested two attached magnets while playing a game. X-ray imaging revealed that the magnets had passed down to the large intestine. He was administered laxatives for 2 d without any progress; therefore, the magnets were removed endoscopically. The third patient was a 7-year-old boy who ingested a coin while playing, which was found to be in the stomach radiologically and remained there for 3 mo.

Data about the method of extraction were available in 107/152 (70.4%) patients with FB ingestion; spontaneous passage was noted in 54 (35.5%), endoscopic removal in 46 (30.3%), laparotomy in 5 (3.3%) (all after magnets ingestion), and direct laryngoscopy in 2 (1.3%); while in the remaining 45 (29.6%) patients nothing was removed as they ingested chemicals (n = 31, 20.4%) or medications (n = 14, 9.2%). Among patients who passed the FB spontaneously, 34 (59.7%) passed it within the first 24 h of admission, 13 (22.8%) passed it between 1 and 2 d, 10 (17.5%) passed it after 3 d, and one patient had missing data. Three patients underwent endoscopic removal of one FB and spontaneous passage of the other.

Pharmacological therapy was required for 105/148 (70.9%) patients; 79/105 (75.2%) in the FB group, 22/29 (75.9%) in the caustic group, and 4/14 (28.8%) in the medication group (P = 0.001). The commonest medication was omeprazole (n = 58; 37.9%), which was used more in the caustic group (n = 19/28, 67.9%) than in the FB (n = 37/104, 25.9%) and medi

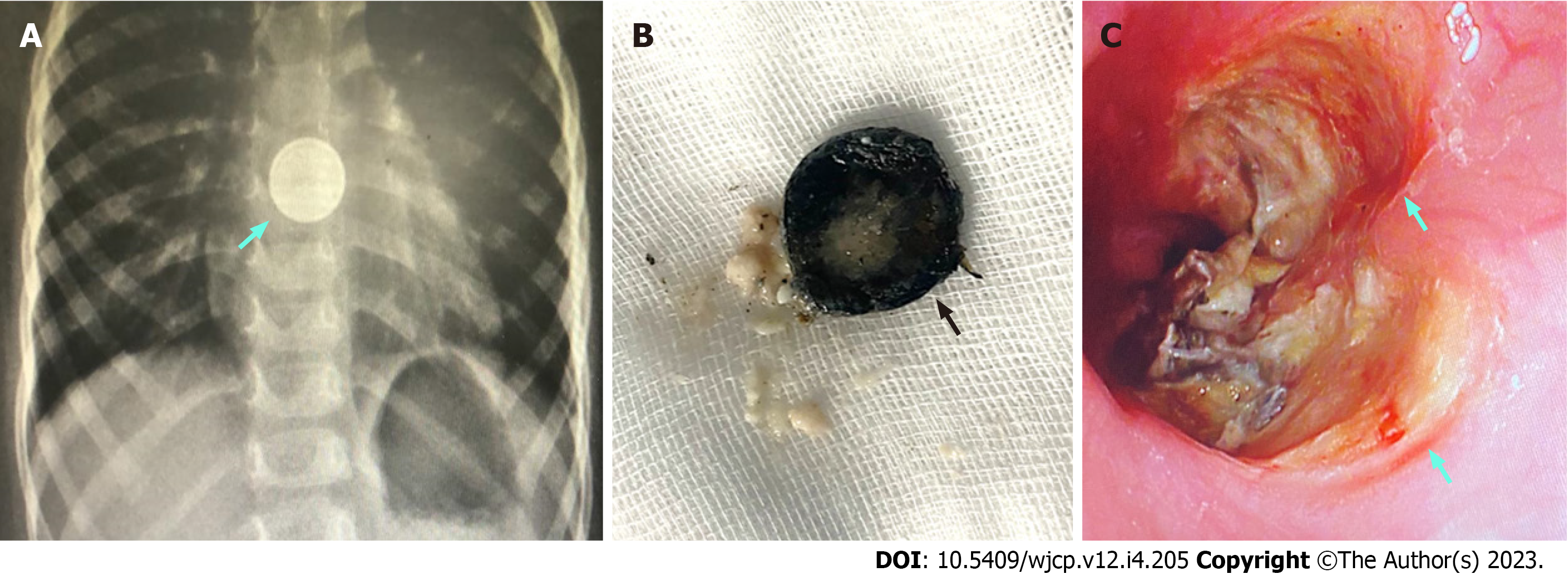

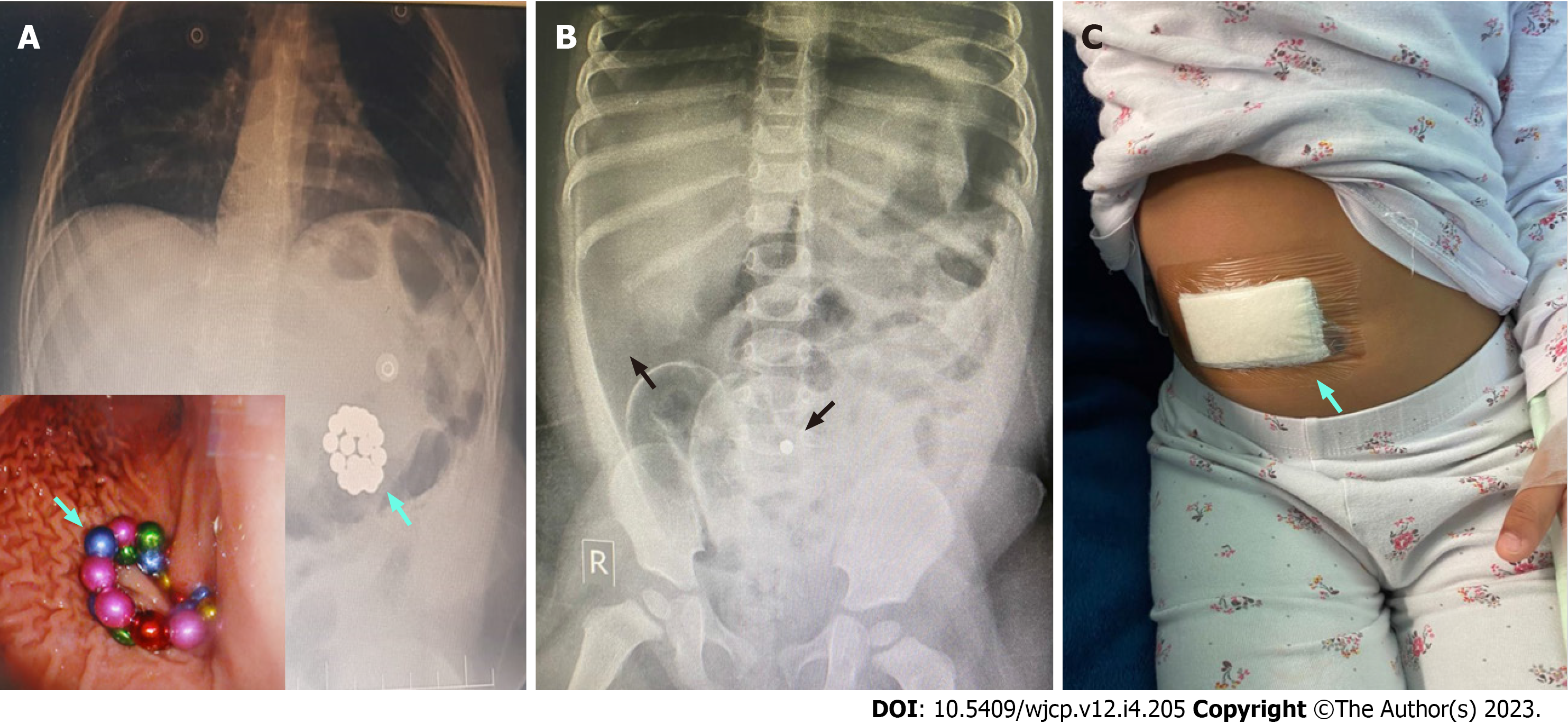

Seven types of endoscopic and surgical complications were detected in 39 (26.4%) out of 148 patients with available data (Table 5). Some patients experienced more than one complication. Overall, patients who ingested caustics had more complications than those in the other groups (P = 0.036) in the form of mucosal erythema (P = 0.005) and strictures (P = 0.019). Gastrointestinal perforation developed in the FB group only (n = 5, 3.4%) and was more with magnet ingestion (4 patients) than with other FB types (one with battery and none with others) (P < 0.001). Examples of complications caused by battery and magnet bead ingestion are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. Patients who ingested the medications showed no endoscopic or surgical complications. Data from follow-up out-patient visits were available for 49 (32%) patients. Median follow-up period was 2 (IQR = 1.7-6.2) wk.

| Complication | Total, n = 1481 (96.7) | FB, n = 104 (70.3) | Caustic, n = 30 (20.3) | Medication, n = 14 (9.6) | P valuea |

| Erythema | 16 (10.8) | 8 (7.7) | 8 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.005b |

| Ulcer | 14 (9.5) | 10 (9.6) | 4 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.369 |

| Mucosal erosions | 9 (6.1) | 9 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.132 |

| Hemorrhage | 6 (4.1) | 6 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.266 |

| Perforation | 5 (3.4) | 5 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.335 |

| Airway edema | 5 (3.4) | 2 (1.9) | 3 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.074 |

| Stricture | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.019b |

| Total | 39 (26.4) | 28 (26.9) | 11 (36.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.036b |

A comparison between the FB and caustic groups with respect to the presence or absence of endoscopic and surgical complications is shown in Table 6. In patients with FB ingestion, patients aged < 1 year (P = 0.042), those with middle or low SES (P = 0.028), and those with more symptoms at presentation (P = 0.027) had more complications. Both the FB and caustic groups with complications had longer hospital stays (P < 0.001) than those without. There were no significant differences in sex, nationality, maternal occupation, number of siblings, presence of witnesses, time to presentation, number and type of ingested FBs, or anatomical location.

| Variable | FB complications, n = 104 | P value | Caustic complications, n = 31 | P value | ||

| Yes, n = 28 (26.9) | No, n = 76 (73.1) | Yes, n = 11 (35.5) | No, n = 20 (64.5) | |||

| Sex | 0.661a | 1.000a | ||||

| Male | 16 (57.1) | 39 (51.3) | 7 (63.6) | 13 (68.4) | ||

| Female | 12 (42.9) | 37 (48.7) | 4 (36.4) | 6 (31.6) | ||

| Nationality | 0.775a | 0.199a | ||||

| Bahraini | 24 (85.7) | 61 (80.3) | 10 (90.9) | 12 (63.2) | ||

| Non-Bahraini | 4 (14.3) | 15 (19.7) | 1 (9.1) | 7 (36.8) | ||

| Socioeconomic status (n = 74) | 0.028b | 0.059b | ||||

| Low | 9 (42.9) | 16 (30.2) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (12.5) | ||

| Medium | 10 (47.6) | 15 (28.3) | 4 (57.1) | 1 (12.5) | ||

| High | 2 (9.5) | 22 (41.5) | 1 (14.3) | 6 (75.0) | ||

| Working mother (n = 74) | 4/21 (19.0) | 24/53 (45.3) | 0.061a | 1/7 (14.3) | 3/8 (37.5) | 0.569a |

| Number of siblings, (n = 74) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 0.355c | 3 (1-5) | 3 (3-4) | 0.779c |

| Age at presentation (yr), (n = 103) | 2.8 (1.5-4.2) | 3.4 (2.2-5.7) | 0.069c | 1.5 (0.9-2.5) | 1.9 (1.6-2.7) | 0.185c |

| Age group (yr) (n = 103) | 0.042b | 0.181b | ||||

| 0-1 | 11 (39.3) | 11 (14.7) | 8 (72.7) | 9 (47.4) | ||

| 2-3 | 9 (32.1) | 35 (46.7) | 2 (18.2) | 8 (42.1) | ||

| 4-5 | 4 (14.3) | 20 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (10.5) | ||

| ≥ 6 | 4 (14.3) | 9 (12.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Presence of ingestion witness (n = 93) | 12/27 (44.4) | 25/66 (37.9) | 0.643a | 4/10 (40) | 10 (55.6) | 0.695a |

| Time to presentation (h), (n = 96) | 3 (1-8.5) | 2 (1-5) | 0.325c | 1 (0.3-3.0) | 2 (0.5-6.0) | 0.155c |

| Length of stay (d), (n = 102) | 2 (1-4) | 1 (0-1) | < 0.001c | 7 (2-12) | 1 (0-2) | < 0.001c |

| Number of ingested FBs/materials per patientc | 0.372b | 1.000b | ||||

| 1 | 18 (64.3) | 60 (78.9) | 11 (100) | 18 (94.7) | ||

| 2-5 | 6 (21.4) | 12 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | ||

| 6-10 | 1 (3.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| > 10 | 3 (10.7) | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Type of FBs | 0.384b | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Battery | 15 (53.6) | 34 (44.7) | 0.508a | NA | NA | NA |

| Metal/sharp object | 6 (21.4) | 23 (30.3) | 0.464a | NA | NA | NA |

| Magnets | 6 (21.4) | 9 (11.8) | 0.224a | NA | NA | NA |

| Coin | 1 (3.6) | 7 (9.2) | 0.679a | NA | NA | NA |

| Food bolus1 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.9) | 0.562a | NA | NA | NA |

| Anatomical location | 0.682b | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Esophagus | 3 (11.1) | 13 (17.3) | 0.550a | NA | NA | NA |

| Stomach | 16 (59.3) | 38 (50.7) | 0.504a | NA | NA | NA |

| Bowel | 8 (29.6) | 23 (30.7) | 1.000a | NA | NA | NA |

| Clinical presentations | 0.027a | 1.000a | ||||

| Symptomatic | 19 (67.9) | 32 (42.1) | 9 (90) | 17 (89.5) | ||

| Asymptomatic | 9 (32.1) | 44 (57.9) | 1 (10) | 2 (10.5) | ||

This study observed an increasing trend in the incidence of accidental ingestion among children. This may be attributed to the increasing number of battery-powered electronic devices and the increased incidence of disc battery ingestion over the past several years[2,5].

The present study showed a male predominance among children with accidental ingestions, where boys accounted for 55.7%. Some accidental ingestion patterns may also be related to sex[6]. In fact, there was a consensus among all the reviewed studies that boys form the majority of children with accidental ingestion (Table 7)[2,4,6-17]. However, there were some variations in percentages. For instance, Dereci et al[13] from Turkey showed that boys accounted for 56%, which is similar to our study. However, Diaconescu et al[14] reported a male predominance, but with a lower percentage (52.45%), while Chan et al[9] reported a higher proportion of boys (80%). This finding may be explained by the fact that boys are more active and explore more[16]. However, some FBs are more accessible to girls than to boys and vice versa[6]. For instance, girls frequently consume jewelry and hair products[6]. This finding was confirmed in the present study. In a study by Orsagh-Yentis et al[6], girls were 2.5 times more likely to swallow jewelry than boys. Speidel et al[4] also found that girls were at higher risk of sharp object ingestion.

| Ref. | Country | n | Age (yr)1 | Sex | Two most common FBs (%) | Two most common symptoms (%) | Two most common sites of FB (%) |

| Our study | Bahrain2 | 153 | 2.8 (1.8-4.4) | M > F | Battery (32), metals/sharps (21) | Vomiting (29), abdominal pain (16) | Stomach (44), small intestine (15) |

| Al-Salem et al[11], 1995 | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | 40 | 8.5 (5 mo-8) | M > F | Coins (43), metallic dog toy | NR | Esophagus (60), stomach (38) |

| Dereci et al[13], 2015 | Turkey | 64 | 5.7 ± 4.6 | M > F | Coin (37), pin (8) | Dysphagia (24), cough (8) | Esophagus (56), stomach (16) |

| Kalra et al[16], 2022 | India | 100 | 5.0 ± 14.4 | M > F | Coin (65), battery cell (13) | FB sensation (55), vomiting (54) | Just below the cricopharynx (89) |

| Lee et al[10], 2016 | Korea | 76 | 3.1 ± 3.1 | M > F | Coins (22), button battery (16) | Chest discomfort, abdominal pain (9) | FBs: Stomach (40), unknown (28). Batteries: Duodenum (50), stomach (42) |

| Chan et al[9], 2002 | Taiwan | 25 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | M > F | Button battery | Abdominal pain (8), dyspnea (4) | Stomach (52), small intestine (8) |

| Lin et al[15], 2007 | Taiwan | 87 | 3.4 (6 mo-13) | M > F | Coins (57), button battery (22) | Odynophagia, cough (84) | Esophagus (51), stomach (45) |

| Khorana et al[17], 2019 | Thailand | 194 | 43.5 (21-72) mo | M > F | Coin (41), button battery (17) | Vomiting (45), dysphagia (27) | Esophagus (37), stomach (29) |

| Uba et al[7], 2002 | Nigeria | 108 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | M > F | Coins (80), bottle caps (7) | Drooling (34), regurgitation (17) | Esophagus (52), hypopharynx (33) |

| Adedeji et al[12], 2013 | Nigeria | 28 | 32.1 (2-75) | M > F | Alkali (79), acid (14) | NR | NR |

| Diaconescu et al[14], 2016 | Romania | 61 | 3.3 ± 4.7 | M > F | Coins (26), metals (13) | Abdominal pain (56), vomiting (34) | NR |

| Antoniou and Christopoulos-Geroulanos[2], 2011 | Greece | 675 | 3.3 (4 mo-14) | M > F | Coins (32), safety pins (21) | Retrosternal pain, drooling | Stomach (58), bowel (33) |

| Speidel et al[4], 2020 | Germany | 1199 | 3.3 ± 3.2 | M > F | Coin (19), metal (16) | Retching and vomiting (30), coughing (8) | NR |

| Little et al[8], 2006 | United States | 555 | 3.2 (2 mo-19) | M > F | Coins (88), round batteries | Dysphagia (37), drooling (31) | Esophagus (99) |

| Orsagh-Yentis et al[6], 2019 | United States | 29893 | < 6 | M > F | Coins (62), toys (10) | NR | NR |

The current study found that the median age at presentation was 2.8 years, and the most frequent age group was between 2-3 years old, accounting for 43.4%. This finding is consistent with several other studies showing that the toddler age group is the most frequent risk factor for accidental ingestion[2,4,6-10,14,17]. This high prevalence of accidental ingestion in younger age groups can be attributed to the exploratory habits of these children[14]. Furthermore, children in the oral phase are prone to ingesting objects while crawling and playing[7]. Several studies have attributed the high prevalence of FB ingestion to the accessibility of FBs in a child’s environment, especially because this age group has the desire to explore their surroundings[1,6,16,18]. However, few studies have reported older age groups up to adulthood[11,13,15,16,18].

In the current study, we evaluated families’ SES as a risk factor for the increased incidence of accidental ingestion, as the child might be left alone at home unwitnessed by the parents/caregivers owing to their work obligations, as stated by Kalra et al[16]. Despite that, we did not observe an overall significant difference between families of different SES. How

In this study, 57.3% (86/150) of the patients were symptomatic at presentation. This is comparable to the studies by Speidel et al[4] and Khorana et al[17], where the percentages of symptomatic patients were 51.6% and 55.67%, respectively. However, studies by Uba et al[7] and Diaconescu et al[14] reported higher percentages of symptomatic patients (85% and 70.5%, respectively). In contrast, Chan et al[9] and Lee et al[10] reported very low percentages of symptomatic patients, with 12% and 9.2%, respectively. This variation in the percentage of symptomatic patients who ingested FBs or other materials can be attributed to the differences in the time from ingestion to presentation and the shape, type, location, and amount of the ingested object[14,15].

Overall, the most frequent presenting symptom in our study was vomiting (29.3%). In the literature review, we found variations in the presenting symptoms depending on the type of FBs/materials ingested or the site of the FB impaction[15]. In terms of the type of ingestion, caustic materials exhibited the highest percentage of symptoms (89.7%) in this study. A lower percentage of symptomatic patients who ingested cleansers was reported by Speidel et al[4] (53.4%). In the FB group, 48.6% of our patients were symptomatic, and 21.9% had vomiting as the most common symptom. Khorana et al[17] reported a higher percentage of symptomatic patients with FB ingestion (55.67%), and vomiting was also the commonest presenting symptom (23.2%). Moreover, Diaconescu et al[14] reported symptoms in 70.5% of their patients with FB ingestion, yet they mainly presented with abdominal pain (55.73%), followed by vomiting (34.42%). Upon comparison of symptoms according to the lodgment site, most patients with esophageal FBs were symptomatic in our study (87.5%). This was comparable to the percentage reported by Uba et al[7] in patients with esophageal FBs (85%). Drooling of saliva and dysphagia are the main symptoms in patients with esophageal FBs[8,13], while abdominal pain and vomiting are the main symptoms in patients with FBs found in the stomach[14,15]. Diaconescu et al[14] explained the wide variation in presenting symptoms among different studies based on the shape of the FB, duration between the ingestion event and time to presentation, and age of the patient.

In the current study, 42.7% of the children who ingested FBs, caustics, or medications were asymptomatic. This is comparable to the study by Speidel et al[4], who also included the three types of ingested materials, where the percentage of asymptomatic patients was 48.4%. Moreover, Lee et al[10] reported that most of the 76 patients with FB ingestions were asymptomatic (90.8%), which was also the case in our study, but at a lower rate (51.4%). Chan et al[9] also documented that most of the 25 patients with button battery ingestion were asymptomatic (88%). This high percentage of asymp

In this study, the majority of the ingestion scenarios were during the playing time (40.5%) and were unwitnessed (57.4%). Ingestion episodes while playing were also documented by Dereci et al[13] but at a higher rate (72%). Unwit

In our study, the most frequently ingested FBs were batteries (32%), followed by chemical solutions (20.3%). The main source of ingested batteries was unsafe toys (51.2%). Unsafe toys are a source of danger, particularly if their batteries are not locked. This may be due to the ease of swallowing these objects and/or being within reach of the children. However, our findings are not compatible with those of many other studies on the most commonly ingested FBs. Most studies have reported that coins are the most common[2,6-8,10,11,13,14]. This can be explained by the strict inclusion criteria of our study, in which patients were admitted to the hospital for observation and for the inclusion of possible endoscopic procedures. Most patients who ingested coins at our hospital were seen in the Department of Emergency, and if the coin was in the stomach or beyond, the patient was discharged if he or she was asymptomatic. Because a significant number of patients with accidental ingestion present to the hospital without any symptoms, the implementation of specific investigations and diagnostic modalities, such as erect chest radiography, technetium-labelled sucralfate scan, and early esophago

Fortunately, most of our patients did not develop complications (73.6%). However, 26.4% had endoscopic and surgical complications, 10.8% developed mucosal erythema, 9.5% had ulcer, 6.1% had erosions, and 3.4% had gastrointestinal perforation (n = 5). Uba et al[7] illustrated that the most common comorbidities were hemorrhage (15%), perforation (3.7%), and aspiration pneumonitis (2.8%).

In our study, 38.2% (n = 58) of the patients had a spon

This study had several limitations. As this was a retrospective study, missing data, such as patient contact number, presence of a witness, and details of the ingestion scenario, were expected. One of the limitations of this study was that we included only those who had been admitted to the hospital, excluding those who attended the Departments of Accident and Emergency and were discharged home, especially asymptomatic patients and those who ingested metallic coins found in the stomach or beyond. Moreover, the ingestion scenario of some patients was gathered via telephone calls to the child’s parents/guardians after the ingestion episode, which was subject to recall bias. Some parents did not provide consent for endoscopy, especially for children who ingested corrosives, which made the assessment of local injury and gastrointestinal complications difficult. The ingestion of glass is a real challenge because it is radiolucent, and nothing was seen on the X-ray to determine the location. Despite these limitations, this study had many strengths. It is the first study from Bahrain to focus on accidental ingestion in children. This covered all types of accidental ingestion, unlike most other studies, which included the ingestion of only one type of hazardous material. The findings of this study are particularly important for health care providers dealing with this group of patients. They are also valuable for policymakers as prevention guidelines and legislation are crucial for protecting children from avoidable risks.

Accidental ingestion of FBs/harmful materials in children is a serious problem. Our study showed that boys and toddlers were at a higher such risk. Most children were symp

Accidental ingestion of foreign bodies (FBs) or harmful materials is a common problem in families with children because of their exploratory behavior. This behavior puts them at risk and can cause serious morbidities.

While many studies on accidental ingestion in children have been published from several countries worldwide, no study has been published on this issue in Bahrain. This knowledge gap motivated us to study this health problem in Bahrain.

To evaluate the incidence, demographics, types of FBs/harmful materials ingested, diagnostic methods, management, complications, and outcomes of accidental ingestion in pediatric patients at the main tertiary hospital in Bahrain and compare patients with endoscopic or surgical complications with those without to identify the predicted risk factors.

We retrospectively reviewed and collected the demographic data, clinical presentations, radiological and endoscopic findings, treatments, complications, and outcomes of accidental ingestions in children admitted to the Department of Pediatrics at the Salmaniya Medical Complex, Kingdom of Bahrain, from medical records between 2011 and 2021.

In total, 161 accidental ingestion episodes were documented in 153 children. Male predominance was noted (n = 85, 55.6%). The median age at presentation was 2.8 (interquartile range: 1.8-4.4) years. Most participants ingested FBs (n = 108, 70.6%), followed by caustic chemicals (n = 31, 20.3%) or medications (n = 14, 9.2%). Most patients were symptomatic (n = 86, 57.3%); vomiting was the common symptom (n = 44, 29.3%), followed by abdominal pain (n = 25, 16.7%). Batteries were the most commonly ingested FBs (n = 49, 32%). Unsafe toys were the main source of batteries (n = 22/43, 51.2%). Most episodes occurred while playing (n = 49/131, 37.4%) or unwitnessed (n = 78, 57.4%). Stomach was the common location of FB lodgment, both radiologically (n = 54/123, 43.9%) and endoscopically (n = 31/91, 34%). Of 107/108 (99.1%) patients with FB ingestions, spontaneous passage was noted in 54 (35.5%), endoscopic removal in 46 (30.3%), laparotomy in 5 (3.3%), and direct laryngoscopy in 2 (1.3%). Pharmacological therapy was required in 105 (70.9%) patients. Complications were detected in 39 (26.4%) patients, five of whom had gastrointestinal perforation. Patients who ingested FBs before the age of one year (P = 0.042), those with middle or low socioeconomic status (P = 0.028), and those with more symptoms at presentation (P = 0.027) had more complications.

Accidental ingestion in children is a serious health problem. Symptomatic infants from families with middle or low families have the highest morbidity. Prevention through parental education and government legislation is crucial.

Additional research is required to evaluate the influence of parental awareness, authority regulations, and the provision of safe environments to prevent such serious incidents.

The authors gratefully acknowledge all heath care providers taking care of children with accidental ingestion in the Department of Pediatrics and Pediatric Surgery Division at Salmaniya Medical Complex, Manama, Bahrain.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: Al-Kawther Society for Social Care, 133; National Health Regulation Authority, 11002084.

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: Bahrain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Huang JG, Singapore; Osatakul S, Thailand S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Sahin C, Alver D, Gulcin N, Kurt G, Celayir AC. A rare cause of intestinal perforation: ingestion of magnet. World J Pediatr. 2010;6:369-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Antoniou D, Christopoulos-Geroulanos G. Management of foreign body ingestion and food bolus impaction in children: a retrospective analysis of 675 cases. Turk J Pediatr. 2011;53:381-387. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Marom T, Goldfarb A, Russo E, Roth Y. Battery ingestion in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:849-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Speidel AJ, Wölfle L, Mayer B, Posovszky C. Increase in foreign body and harmful substance ingestion and associated complications in children: a retrospective study of 1199 cases from 2005 to 2017. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brumbaugh DE, Colson SB, Sandoval JA, Karrer FM, Bealer JF, Litovitz T, Kramer RE. Management of button battery-induced hemorrhage in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:585-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Orsagh-Yentis D, McAdams RJ, Roberts KJ, McKenzie LB. Foreign-Body Ingestions of Young Children Treated in US Emergency Departments: 1995-2015. Pediatrics. 2019;143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Uba AF, Sowande AO, Amusa YB, Ogundoyin OO, Chinda JY, Adeyemo AO, Adejuyigbe O. Management of oesophageal foreign bodies in children. East Afr Med J. 2002;79:334-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Little DC, Shah SR, St Peter SD, Calkins CM, Morrow SE, Murphy JP, Sharp RJ, Andrews WS, Holcomb GW 3rd, Ostlie DJ, Snyder CL. Esophageal foreign bodies in the pediatric population: our first 500 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:914-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chan YL, Chang SS, Kao KL, Liao HC, Liaw SJ, Chiu TF, Wu ML, Deng JF. Button battery ingestion: an analysis of 25 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2002;25:169-174. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lee JH, Lee JH, Shim JO, Eun BL, Yoo KH. Foreign Body Ingestion in Children: Should Button Batteries in the Stomach Be Urgently Removed? Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2016;19:20-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Al-Salem AH, Qaisarrudin S, Murugan A, Hammad HA, Talwalker V. Swallowed foreign bodies in children: Aspects of management. Ann Saudi Med. 1995;15:419-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Adedeji TO, Tobih JE, Olaosun AO, Sogebi OA. Corrosive oesophageal injuries: a preventable menace. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dereci S, Koca T, Serdaroğlu F, Akçam M. Foreign body ingestion in children. Turk Pediatri Ars. 2015;50:234-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Diaconescu S, Gimiga N, Sarbu I, Stefanescu G, Olaru C, Ioniuc I, Ciongradi I, Burlea M. Foreign Bodies Ingestion in Children: Experience of 61 Cases in a Pediatric Gastroenterology Unit from Romania. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:1982567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin CH, Chen AC, Tsai JD, Wei SH, Hsueh KC, Lin WC. Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies in children. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2007;23:447-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kalra V, Yadav SPS, Ranga R, Moudgil H, Mangla A. Epidemiological, Clinical and Radiological Profile of Patients with Foreign Body Oesophagus: A Prospective Study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74:443-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Khorana J, Tantivit Y, Phiuphong C, Pattapong S, Siripan S. Foreign Body Ingestion in Pediatrics: Distribution, Management and Complications. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L. Preventing battery ingestions: an analysis of 8648 cases. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1178-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L, White NC, Marsolek M. Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1168-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |