Published online Dec 8, 2012. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v1.i4.34

Revised: October 9, 2012

Accepted: October 20, 2012

Published online: December 8, 2012

Delayed childbearing (DC) is common in most Western countries. The average age of first-time mothers increased in United States from 21.4 years in 1970 to 25.0 years in 2006 and from 25.4 to 30.8 years in Australia in the same period. It is commonly believed that this has no ominous consequences. But several negative consequences of this behavior are described: stillbirth, prematurity, twins, birth anomalies. Age also decreases women’s fertility, thus many couples undergo in vitro fertilization. And we highlight a paradox: medical reproduction techniques decreases their effectiveness with maternal age, but their availability can be an incentive to postpone parenthood. Of course the risks of delayed parenthood involve a minority of cases, but are parents entitled to accept any risk on the behalf of their baby A complete information would make people cautious before deciding to postpone childbearing, though this is often an obliged rather that a free choice: the consumerist society pressure and the difficulty to find an employment have their heavy weight in this choice. But if this choice is not really free, people’s interest is to overcome these pressures and to claim for a real broad choice on when becoming parent, despite the pressures made by their cultural environment to postpone parenthood. Moreover, even reproductive techniques have some risks. Unfortunately, mass media often praise and endorse DC, disregarding the increase of premature babies born because of DC, a real alarm for public health. Pediatricians should discourage the culture that makes DC a normal event.

-

Citation: Bellieni CV. Neonatal risks from

in vitro fertilization and delayed motherhood. World J Clin Pediatr 2012; 1(4): 34-36 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v1/i4/34.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v1.i4.34

In most countries, women delay the age of the first pregnancy. A recent survey showed that the average age of first-time mothers increased in United States from 21.4 years in 1970 to 25.0 years in 2006, with a decrease in the rate of those younger than 20 years of age, and a relevant increase of those older than 35[1]. In most countries the average age at first birth has increased in the same years, with a minimum increase in Sweden (2.9 years) and the maximum (4.6 years) in Denmark; the average age at first birth in 2006 ranged from 25.0 years in the United States to 29.4 years in Switzerland[1]. The median age of women giving birth in Australia reached a low of 25.4 in 1971 and rose to a peak of 30.8 in 2006. Consequences of delayed childbearing (DC) were an increase of sterility in the population, and consequently an increase of fertility treatments: but fertility rates decline with age despite in vitro fertilization (IVF) techniques[2,3]. Nevertheless, the number of women older than 35 or even 40 years of age who are using IVF is increasing and the average age of the women attending the clinics is increasing as well[4]. DC has become more socially acceptable, with subsequent negative connotations associated with younger motherhood[5].

How can this generalized tendency to DC be explained The first answer is that a pregnancy can interfere with a woman’s career[6]; this interference is not accepted in a society where women massively enter the job world for equality reasons and also for economic needs. It is well known that financial concerns related to childbirth may affect the take-up of maternity leave allowances[7] and that new parents have difficulties in taking maternity leave because of their financial situation[8]. Nevertheless, decisions taken under the pressure of economic needs and mass media cultural pressure are far from being a free choice. Women perceive a lack of choice in the timing of when to start a family: “Women do not perceive that they have ultimate control when it comes to the timing of childbearing”[9] and some authors report that “the choice to delay motherhood is not so voluntary”[10]. Poor understanding of the links between childbearing after age 35, pregnancy complications and increased risk of adverse infant outcomes limit adults’ ability to make informed decisions about timing of child bearing[11].

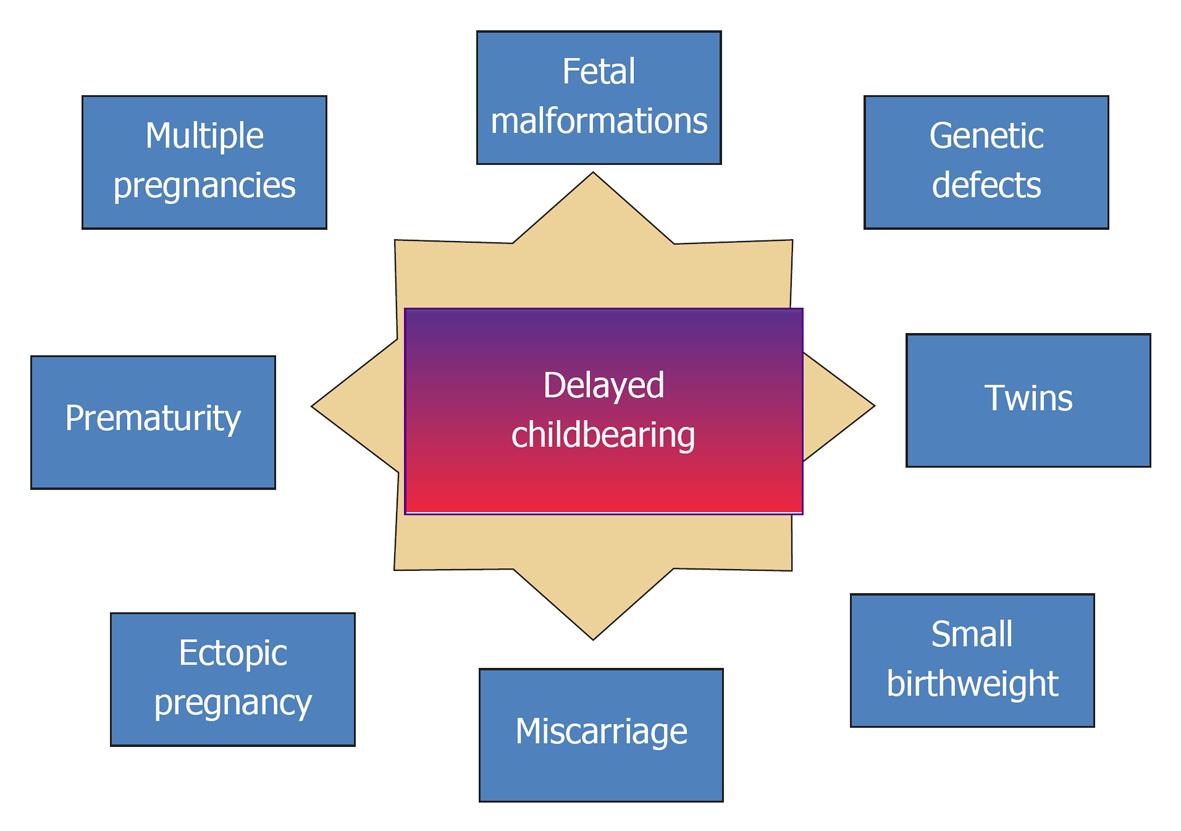

But, if this is not ultimately a free choice, is DC at least in the interest of babies Some commentators argue that having a baby late in age can give the baby psychological advantages[12]. Nonetheless, DC brings risks to the baby-to-be[13,14]: prematurity and consequently higher risk of brain damage[15], aneuploidy, stillbirth, miscarriage are some of the risks (Figure 1). IVF, with a higher rate of prematurity[16], small birth weight[17] and malformations[18], as well as risk of imprinting diseases[19-21] does not improve this situation. Recent reviews reported these data in detail for DC[22,23] and for IVF[24,25], though Davies et al[26] recently reported that “the increased risk of birth defects associated with IVF was no longer significant after adjustment for parental factors”; nevertheless, “the risk of birth defects associated with intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection remained increased after multivariate adjustment, although the possibility of residual confounding cannot be excluded”.

These risks can be accepted by parents, but are parents entitled to accept any risk on the behalf of their baby When they choose between two healing options, the answer is “yes”, if the risk is balanced by possible benefits[27]. But choosing DC, they choose between a more risky and a less risky option; this is a paradox, because you should not choose the worst option if its consequences will not affect only you, but also others. Parents have only one option: to behave in the less risky way for the baby, and delaying childbearing beyond a certain threshold is risky. Unfortunately, mass media often praise and endorse DC, disregarding the increase of premature babies induced by several factors, among which DC.

In some cases, DC is not a choice, but is obliged by events: in this case, parents should thoroughly consider their reproductive decisions, trying to take a really autonomous and informed decision.

Any parental choice that is not free and that can provoke damages to the babies should be discouraged, and women should be safeguarded from external pressures, when this can harm their babies. Pediatricians and neonatologists should play an active role in this matter[28]: they should contrast economic pressures on motherhood, and correctly inform parents-to-be on the pros and cons of DC. They should use their media and agencies to make it clear that an excessive delay in procreating is medically contraindicated in the interest of the babies-to-be. Their message to the information leaders and to politicians should be clear: DC is one of the causes of an epidemic in prematurity and other health risks, ominous for babies, families and social wellbeing.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Keith James Collard, Peninsula Allied Health Centre, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, PL6 8BH, United Kingdom

S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Matthews TJ, Hamilton BE. Delayed childbearing: more women are having their first child later in life. NCHS Data Brief. 2009;1-8. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Serour G, Mansour R, Serour A, Aboulghar M, Amin Y, Kamal O, Al-Inany H, Aboulghar M. Analysis of 2,386 consecutive cycles of in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection using autologous oocytes in women aged 40 years and above. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1707-1712. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Spandorfer SD, Bendikson K, Dragisic K, Schattman G, Davis OK, Rosenwaks Z. Outcome of in vitro fertilization in women 45 years and older who use autologous oocytes. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:74-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Andersen AN, Goossens V, Ferraretti AP, Bhattacharya S, Felberbaum R, de Mouzon J, Nygren KG. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2004: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:756-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Benzies K, Tough S, Tofflemire K, Frick C, Faber A, Newburn-Cook C. Factors influencing women's decisions about timing of motherhood. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:625-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bianchi SM. Changing families, changing workplaces. Future Child. 2011;21:15-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang X. Earnings of women with and without children. Perspectives. 2009;Statistics Canada Ed Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-001-x/2009103/pdf/10823-eng.pdf. |

| 8. | Beaupré P, Cloutier E. Navigating Family Transitions: Evidence from the General Social Survey, 2006. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-625-x/89-625-x2007002-eng.htm. |

| 9. | Cooke A, Mills TA, Lavender T. Advanced maternal age: delayed childbearing is rarely a conscious choice a qualitative study of women's views and experiences. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Petropanagos A. Reproductive 'choice' and egg freezing. Cancer Treat Res. 2010;156:223-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tough S, Benzies K, Fraser-Lee N, Newburn-Cook C. Factors influencing childbearing decisions and knowledge of perinatal risks among Canadian men and women. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11:189-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Allott S. Will older mothers regret their choice 2008. Available from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/you/article-1073430/Late-baby-bloomers-Will-older-mothers-regret-choice.html. |

| 13. | Prysak M, Lorenz RP, Kisly A. Pregnancy outcome in nulliparous women 35 years and older. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:65-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ziadeh S, Yahaya A. Pregnancy outcome at age 40 and older. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2001;265:30-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bellieni CV, Bagnoli F, Tei M, De Filippo M, Perrone S, Buonocore G. Increased risk of brain injury in IVF babies. Minerva Pediatr. 2011;63:445-448. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Grady R, Alavi N, Vale R, Khandwala M, McDonald SD. Elective single embryo transfer and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:324-331. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kalra SK, Ratcliffe SJ, Coutifaris C, Molinaro T, Barnhart KT. Ovarian stimulation and low birth weight in newborns conceived through in vitro fertilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:863-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sagot P, Bechoua S, Ferdynus C, Facy A, Flamm X, Gouyon JB, Jimenez C. Similarly increased congenital anomaly rates after intrauterine insemination and IVF technologies: a retrospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:902-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gosden R, Trasler J, Lucifero D, Faddy M. Rare congenital disorders, imprinted genes, and assisted reproductive technology. Lancet. 2003;361:1975-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Le Bouc Y, Rossignol S, Azzi S, Steunou V, Netchine I, Gicquel C. Epigenetics, genomic imprinting and assisted reproductive technology. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2010;71:237-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rossignol S, Steunou V, Chalas C, Kerjean A, Rigolet M, Viegas-Pequignot E, Jouannet P, Le Bouc Y, Gicquel C. The epigenetic imprinting defect of patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome born after assisted reproductive technology is not restricted to the 11p15 region. J Med Genet. 2006;43:902-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Balasch J, Gratacós E. Delayed childbearing: effects on fertility and the outcome of pregnancy. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2011;29:263-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jahromi BN, Husseini Z. Pregnancy outcome at maternal age 40 and older. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;47:318-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sutcliffe AG, Ludwig M. Outcome of assisted reproduction. Lancet. 2007;370:351-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shiota K, Yamada S. Assisted reproductive technologies and birth defects. Congenit Anom (Kyoto). 2005;45:39-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 573] [Cited by in RCA: 558] [Article Influence: 42.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Davies MJ, Moore VM, Willson KJ, Van Essen P, Priest K, Scott H, Haan EA, Chan A. Reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1803-1813. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Bellieni C, Buonocore G. Assisted procreation: too little consideration for the babies. Ethics Med. 2006;22:93-98. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Dehan M. [The role of infertility treatment in very premature births in France. The point of view of the neonatologist]. Contracept Fertil Sex. 1998;26:512-516. [PubMed] |